What is rheumatoid arthritis

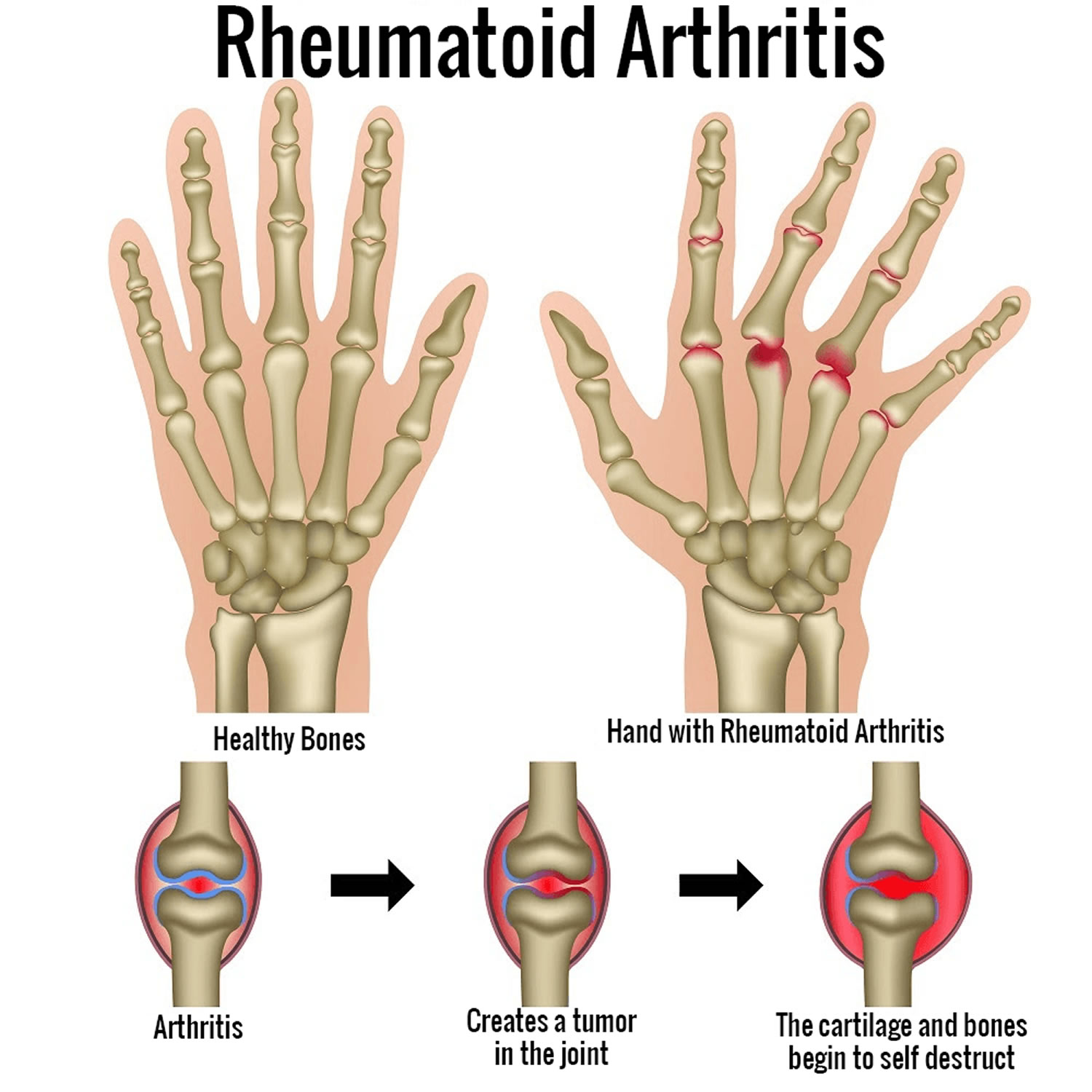

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease where your immune system mistakenly attacks the linings of your joints. This results in joint pain, stiffness, swelling, and destruction. Rheumatoid arthritis patients typically experience morning stiffness. Joints are where two or more bones join together, such as at your knees, hips, or shoulders. Joint inflammation over time leads to the destruction of the joint with cartilage and bone erosion 1. If left untreated, they could appear small focal necrosis, adhesion of granulation, and fibrous tissue on the articular surface, which lead to progressive joint ankylosis (stiffness of a joint due to abnormal adhesion and rigidity of the joint), destruction, deformities, and disability 2. If you have rheumatoid arthritis, you also may feel sick and tired, and sometimes get fevers.

In some people, rheumatoid arthritis can also damage a wide variety of body systems, including the skin, eyes, lungs, heart and blood vessels.

Rheumatoid arthritis causes pain, swelling, and stiffness. If joints on one side of your body have rheumatoid arthritis, usually those joints on the other side do too. This disease often occurs in more than one joint. Rheumatoid arthritis can affect any joint in the body. In some people, rheumatoid arthritis can also cause the lining of the joints to become damaged and deformed.

The onset of rheumatoid arthritis is usually from the age of 35 to 60 years, with remission and exacerbation 3. Rheumatoid arthritis can also afflict young children even before the age of 16 years, referred to as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), which is similar to rheumatoid arthritis except that rheumatoid factor is not found 4, 5.

- Although rheumatoid arthritis can affect any joint in the body, rheumatoid arthritis is most commonly found in the hands, wrists, feet, and knees. Usually, if it is found in one hand, it will appear in the other as well.

- Sometimes rheumatoid arthritis can cause problems with body parts other than your joints such as your heart, lungs, eyes, or mouth.

- Rheumatoid arthritis usually lasts many years or an entire lifetime. For some people, rheumatoid arthritis can last for only a few months to a few years with treatment, although this is rare.

- Rheumatoid arthritis with a symptom duration of fewer than six months is defined as early rheumatoid arthritis, and when the symptoms have been present for more than six months, it is defined as established rheumatoid arthritis 3.

- The symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis (pain, swelling, stiffness) can get worse for some periods of time (called a “flareup”) and then get better for some periods of time.

Rheumatoid arthritis affects 0.5% to 1.0% of the population worldwide 6 and it decreases significantly from north to South (in the northern hemisphere) 7. The urban areas have a higher incidence over rural areas 8.

For unknown reasons, more women than men (females two to three times than males) get rheumatoid arthritis, and it usually develops in middle age 9, with a lifetime risk of rheumatoid arthritis 3.6% in women compared to 1.7% in men 10. Rheumatoid arthritis risk also increases with age, with a peak incidence between age 65 to 80 years of age 11. Having a family member with rheumatoid arthritis also increases the odds of developing rheumatoid arthritis 12. As there is a strong genetic element to rheumatoid arthritis, it is very helpful to let your doctor know if other members of your family are also affected by rheumatoid arthritis or another auto-immune condition.

Diagnosing rheumatoid arthritis quickly is important, because early treatment can prevent it getting worse and reduce the risk of joint damage. Any person who is suspected of having rheumatoid arthritis should be referred to a specialist rheumatologist. Early referral is important so that disease modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) may be prescribed as soon as possible so as to slow or halt the disease process. Delay in referral or receiving a definitive diagnosis and treatment can result in significant costs to the individual, particularly those who are employed. This is because joint damage occurs most rapidly in the early stages of the disease, and often the treatment drugs can take several months to work.

Investigations can be normal in rheumatoid arthritis, particularly early in the disease, and therefore there is no need to wait for results before the referral. In cases where it is felt that the most likely diagnosis is one of the conditions mentioned above then it is probable that you would be reviewed with the results of your investigations as these do not require an urgent referral.

There’s no cure for rheumatoid arthritis. However, early diagnosis and appropriate treatment enables many people with rheumatoid arthritis to have periods of months or even years between flares. The goals of treatment for rheumatoid arthritis are to reduce joint inflammation and pain, maximize joint function, and prevent joint destruction and deformity. This can help them to lead full lives and continue regular employment.

The main treatment options include:

- medicine that is taken long term to relieve symptoms and slow the progress of the condition

- supportive treatments, such as physiotherapy and occupational therapy, to help keep you mobile and manage any problems you have with daily activities

- surgery to correct any joint problems that develop.

Today, the standard of care is early treatment with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) 13. DMARDs work by blocking the effects of the chemicals released when your immune system attacks your joints, which could otherwise cause further damage to nearby bones, tendons, ligaments and cartilage. You may have to try 2 or 3 types of DMARD before you find the one that’s most suitable for you. Once you and your doctor find the most suitable DMARD, you’ll usually have to take the medicine long term. Side effects of DMARDs vary but may include liver damage and severe lung infections.

Despite treatment, many patients progress to disability and suffer significant morbidity over time. A comprehensive pharmacological and non-pharmacological support (physical therapy, counseling, and patient education) is required to improve clinical outcomes.

Figure 1. Rheumatoid arthritis

Footnote: A classic example of joint deformities associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Boutonniere deformity is visible in the 5th digit of the right hand, Swan neck deformity in the 5th digit of the left hand, and hallux valgus can be seen in the foot.

[Source 3 ]Figure 2. Rheumatoid arthritis stages

Footnotes: Stages of rheumatoid arthritis as defined by the American College of Rheumatology

- Stage 1: No destructive changes on x-rays

- Stage 2: Presence of x-ray evidence of periarticular osteoporosis, subchondral bone destruction but no joint deformity

- Stage 3: X-ray evidence of cartilage and bone destruction in addition to joint deformity and periarticular osteoporosis

- Stage 4: Presence of fibrous ankylosis along with stage 3 features

- Stage 5: Presence of bony ankylosis along with advanced osteoporosis

How common is rheumatoid arthritis ?

- Rheumatoid arthritis is less common than other kinds of arthritis such as osteoarthritis.

- More than 1 million people in the United States have rheumatoid arthritis.

- Women are more likely to have rheumatoid arthritis than men. About 7 out of every 10 people with rheumatoid arthritis are women.

- Although rheumatoid arthritis can happen at any age, it usually develops between ages 30 and 50.

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment with your doctor if you have persistent discomfort and swelling in your joints.

Rheumatoid arthritis causes

The cause of rheumatoid arthritis is unknown, but researchers think the condition may be passed down in families. The pain and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis happen when your immune system (the system of the body that helps defend you from germs) attacks the healthy lining of your joints. Doctors are not sure why the immune system in some people attacks their joints, although a genetic component appears likely. While your genes don’t actually cause rheumatoid arthritis, they can make you more susceptible to environmental factors — such as infection with certain viruses and bacteria — that may trigger the disease.

- Rheumatoid arthritis occurs when your immune system attacks the synovium — the lining of the membranes that surround your joints.

The resulting inflammation thickens the synovium, which can eventually destroy the cartilage and bone within the joint.

The tendons and ligaments that hold the joint together weaken and stretch. Gradually, the joint loses its shape and alignment.

Risk factors

Factors that may increase your risk of rheumatoid arthritis include:

- Your sex. Women are more likely than men to develop rheumatoid arthritis.

- Age. Rheumatoid arthritis can occur at any age, but it most commonly begins between the ages of 40 and 60.

- Family history. If a member of your family has rheumatoid arthritis, you may have an increased risk of the disease.

- Smoking. Cigarette smoking increases your risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis, particularly if you have a genetic predisposition for developing the disease. Smoking also appears to be associated with greater disease severity.

- Environmental exposures. Although uncertain and poorly understood, some exposures such as asbestos or silica may increase the risk for developing rheumatoid arthritis. Emergency workers exposed to dust from the collapse of the World Trade Center are at higher risk of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis.

- Obesity. People who are overweight or obese appear to be at somewhat higher risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis, especially in women diagnosed with the disease when they were 55 or younger.

Signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis

Signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis may include:

- Tender, warm, swollen joints

- The joint pain associated with rheumatoid arthritis is usually a throbbing and aching pain. It is often worse in the mornings and after a period of inactivity.

- The lining of joints affected by rheumatoid arthritis become inflamed, which can cause the joints to swell, and become hot and tender to touch. In some people, firm swellings called rheumatoid nodules can also develop under the skin around affected joints.

- Joint stiffness that is usually worse in the mornings and after inactivity

- Joints affected by rheumatoid arthritis can feel stiff. For example, if your hands are affected, you may not be able to fully bend your fingers or form a fist. Like joint pain, the stiffness is often worse in the morning or after a period of inactivity. Morning stiffness that is a symptom of another type of arthritis, called osteoarthritis, usually wears off within 30 minutes of getting up, but morning stiffness in rheumatoid arthritis often lasts longer than this.

- Fatigue, tiredness or a lack of energy, fever, sweating, a poor appetite and weight loss

Early rheumatoid arthritis tends to affect your smaller joints first — particularly the joints that attach your fingers to your hands and your toes to your feet.

As the disease progresses, symptoms often spread to the wrists, knees, ankles, elbows, hips and shoulders. In most cases, symptoms occur in the same joints on both sides of your body.

The symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis often develop gradually over several weeks, but some cases can progress quickly over a number of days.

The symptoms vary from person to person. They may come and go, or change over time. You may experience flares when your condition deteriorates and your symptoms become worse.

About 40 percent of the people who have rheumatoid arthritis also experience signs and symptoms that don’t involve the joints. Rheumatoid arthritis can affect many non-joint structures, including:

- Skin

- Eyes

- Lungs

- Heart

- Kidneys

- Salivary glands

- Nerve tissue

- Bone marrow

- Blood vessels

Rheumatoid arthritis signs and symptoms may vary in severity and may even come and go. Periods of increased disease activity, called flares, alternate with periods of relative remission — when the swelling and pain fade or disappear. Over time, rheumatoid arthritis can cause joints to deform and shift out of place.

Rheumatoid arthritis complications

Rheumatoid arthritis increases your risk of developing:

- Osteoporosis. Rheumatoid arthritis itself, along with some medications used for treating rheumatoid arthritis, can increase your risk of osteoporosis — a condition that weakens your bones and makes them more prone to fracture.

- Rheumatoid nodules. These firm bumps of tissue most commonly form around pressure points, such as the elbows. However, these nodules can form anywhere in the body, including the lungs.

- Dry eyes and mouth. People who have rheumatoid arthritis are much more likely to experience Sjogren’s syndrome, a disorder that decreases the amount of moisture in your eyes and mouth.

- Infections. The disease itself and many of the medications used to combat rheumatoid arthritis can impair the immune system, leading to increased infections.

- Abnormal body composition. The proportion of fat compared to lean mass is often higher in people who have rheumatoid arthritis, even in people who have a normal body mass index (BMI).

- Carpal tunnel syndrome. If rheumatoid arthritis affects your wrists, the inflammation can compress the nerve that serves most of your hand and fingers.

- Heart problems. Rheumatoid arthritis can increase your risk of hardened and blocked arteries, as well as inflammation of the sac that encloses your heart (pericarditis).

- Lung disease. People with rheumatoid arthritis have an increased risk of inflammation and scarring of the lung tissues, which can lead to progressive shortness of breath.

- Lymphoma. Rheumatoid arthritis increases the risk of lymphoma, a group of blood cancers that develop in the lymph system.

Complications of rheumatoid arthritis span multiple organ systems and are known to worsen clinical outcomes in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. It is imperative to monitor patients for the development of these complications and quickly alter treatment plans if applicable. Frequent recurrent serious opportunistic infections occur in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, which warrant withholding DMARD therapy until they are treated. The increased frequency of infections in patients with rheumatoid arthritis is thought to be due to underlying immune dysfunction from the disease itself and the use of DMARD therapy 15.

Osteopenia and osteoporosis are complications of the disease itself and can also be associated with drug therapies (glucocorticoids). Patients with rheumatoid arthritis have a 60% to 100% increased risk of fracture compared to the general population 16. Patient factors that increase the risk of this complication in patients with rheumatoid arthritis are the same as those of osteoporosis, including postmenopausal state, low body mass index, and advanced age.

Pleuritis, bronchiolitis, and interstitial fibrosis are also associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Although rare, rheumatoid arthritis treatment with methotrexate and anti-TNF agents can lead to pulmonary injury as well. There is also an increased risk of pulmonary embolism in rheumatoid arthritis.

Coronary artery disease has a strong association with rheumatoid arthritis. rheumatoid arthritis is an independent risk factor for the development of coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease) and accelerates the development of coronary artery disease in these patients 17. Accelerated atherosclerosis is the primary cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis leading to coronary heart disease and peripheral vascular disease 18. There is increased insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus associated with rheumatoid arthritis and is thought to be due to chronic inflammation 19. When treated with specific DMARDs such as hydroxychloroquine, methotrexate, and TNF antagonists, there was a marked improvement in glucose control in these patients 19.

Rheumatoid vasculitis is a rare phenomenon but can have severe complications if present. Clinical presentation ranges from focal digital involvement to severe systemic involvement resembling polyarteritis nodosa 20.

There is an increased risk of venous thromboembolic disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, as stated above, even after adjusting for other risk factors for thromboembolic disease 21. Multiple studies have reported a higher risk of thromboembolic disease in patients receiving TNF inhibitor therapy and JAK inhibitors 22. However, the consensus regarding this association is not well established. Some studies suggest that higher thromboembolic disease with the use of these agents is secondary to higher disease activity rather than an adverse effect of the agents 22.

The secondary form of Sjögren syndrome is associated with rheumatoid arthritis and can have a prevalence of as high as 10% in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and pulmonary disease 23.

Depression is a significant complication of rheumatoid arthritis. It is present in patients with long-term active disease and debilitating physical dysfunction. A 2013 meta-analysis reported a 17% to 39% prevalence of depression in patients with rheumatoid arthritis 24.

Anemia of chronic disease and Felty syndrome are well-documented complications of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis 23. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis also have a greater risk of developing lymphoma with a higher incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in these patients 25. The clinical course of rheumatoid arthritis in these patients is accelerated, and diffuse B-cell lymphoma is often the most common subtype 25.

Rheumatoid arthritis diagnosis

Rheumatoid arthritis can be difficult to diagnose in its early stages because the early signs and symptoms mimic those of many other diseases. There is no one blood test or physical finding to confirm the diagnosis.

During the physical exam, your doctor will check your joints for swelling, redness and warmth. He or she may also check your reflexes and muscle strength.

Traditionally the presence of at least 4 of the following criteria for at least six weeks would classify the patient as having rheumatoid arthritis. These criteria were:

- morning stiffness,

- arthritis of three or more joints,

- arthritis of the hands,

- symmetric arthritis,

- elevated acute phase reactants,

- elevated rheumatoid factor,

- radiologic evidence of rheumatoid arthritis.

These criteria separated inflammatory from non-inflammatory arthritis but were not very specific for rheumatoid arthritis. It was also not sensitive for early-stage rheumatoid arthritis, which was a significant drawback 26.

So specialist criteria have been developed jointly by American and European experts to try to help make a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis in people presenting with new-onset swollen, painful joints (called synovitis) with no obvious cause (American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism 2010 Rheumatoid Arthritis Classification Criteria). The 2010 American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism diagnostic criteria for rheumatoid arthritis are outlined below. It includes four different domains, which are as follows 27:

2010 American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism Diagnostic Criteria for rheumatoid arthritis

- Number and site of involved joints

- 2 to 10 large joints = 1 point (shoulders, elbows, hips, knees, and ankles)

- 1 to 3 small joints = 2 points (metacarpophalangeal joints, proximal interphalangeal joints, second through fifth metatarsophalangeal joints, thumb interphalangeal joints, and wrists)

- 4 to 10 small joints = 3 points

- Greater than 10 joints (including at least 1 small joint) = 5 points

- Serological testing for rheumatoid factor (RF) or anti-citrullinated peptide/protein antibody (anti-CCP)

- Low positive = 2 points

- High positive = 3 points

- Elevated acute phase reactant (erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR] or C-reactive protein [CRP]) = 1 point

- Symptom duration at least six weeks = 1 point

A total score of greater than or equal to 6 classifies the patient as having rheumatoid arthritis 27. It is important to note that joint involvement refers to any swollen or tender joint on examination. Imaging studies may also be used to determine the presence of synovitis/joint involvement. The 2010 American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism criteria excluded distal interphalangeal joints, first carpometacarpal joints, and first metatarsophalangeal joints from this criteria. Also, this criteria may only be applied to those patients where the joint involvement is not better explained by other inflammatory diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus or psoriasis. Specific testing must be obtained to rule out these diseases. The new criteria were noted to better predict the probability of rheumatoid arthritis, have the same sensitivity as the previous criteria for the diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis and have a higher specificity as well as higher negative predictive value 26.

The 2010 American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism Diagnostic Criteria for rheumatoid arthritis should be used with care though as people with osteoarthritis (OA) or a crystal arthritis (gout) could meet the criteria and end up being incorrectly diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, which could have significant consequences for treatment. They have also been developed to classify, not diagnose, rheumatoid arthritis and so should not be used to decide who gets referred.

Blood tests

No blood test can definitively prove or rule out a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, but several tests can show indications of rheumatoid arthritis. People with rheumatoid arthritis often have an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR, or sed rate) or C-reactive protein (CRP), which may indicate the presence of an inflammatory process in the body. Other common blood tests look for rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies.

About 75% to 85% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis will test positive for rheumatoid factor (RF), anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies or both 28. These patients are designated as seropositive rheumatoid arthritis. About 45% to 75% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis test positive for rheumatoid factor (RF). However, the presence of rheumatoid factor is not diagnostic of rheumatoid arthritis. It may be present in other connective tissue diseases, chronic infections, and healthy individuals, although in low titers. Anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (anti-CCP) are found in about 50% of patients with early arthritis, which are subsequently diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. If both rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) antibodies are positive, the sensitivity and specificity of the diagnosis increase substantially. Acute phase reactants, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), are usually elevated in patients with active disease and should be obtained.

Rheumatoid factor are proteins that the immune system produces when it attacks health tissue. About half of all people with rheumatoid arthritis have high levels of rheumatoid factor (RF) in their blood when the disease starts, but about 1 in 20 people without rheumatoid arthritis also test positive.

Anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) are antibodies also produced by the immune system. People who test positive for anti-CCP are very likely to develop rheumatoid arthritis, but not everybody with rheumatoid arthritis has anti-CCP antibody.

Those who test positive for both rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP may be more likely to have severe rheumatoid arthritis requiring higher levels of treatment.

Synovial fluid examination

Synovial fluid examination usually reveals a leukocyte count between 1500 to 25,000/mm³ and is predominantly polymorphonuclear cells. Cell counts higher than 25000/mm³ are rare and can be seen with very active disease; however, they warrant workup to rule out underlying infection. The synovial fluid in rheumatoid arthritis will also reveal low C3 and C4 levels despite elevated serum levels 29.

Imaging tests

Your doctor may recommend X-rays to help track the progression of rheumatoid arthritis in your joints over time. MRI and ultrasound tests can help your doctor judge the severity of the disease in your body. MRI scans is where strong magnetic fields and radio waves are used to produce detailed images of your joints.

With advanced disease, joint involvement on plain X-rays will reveal periarticular osteopenia, joint space narrowing, and bony erosions. Erosions of cartilage and bone are considered pathognomonic findings for rheumatoid arthritis. However, these findings are consistent with advanced disease 30. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasonography are useful in early disease before radiographic evidence of bone erosion occurs 31. A decreased signal from the bone marrow on T1-weighted images and gadolinium-enhanced images indicates bone marrow edema. MRI can also reveal synovial thickening, which has been shown to predict the future presence of bony erosions 32. The clinical utility of MRI and its incorporation into the diagnostic criteria for rheumatoid arthritis remains to be determined.

Assessing your physical ability

If you have been diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, your rheumatologist will do an assessment to see how well you’re coping with everyday tasks.

You may be asked to fill in a questionnaire on how well you can do things like dress, walk and eat, and how good your grip strength is.

This assessment may be repeated after your treatment, to see if you have made any improvements.

Multiple clinical assessment tools have been developed to assist clinicians in determining the disease activity of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. An updated recommendation from the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) in 2019 recommended using the following assessment tools because they met the minimum standard for evaluation per their recommendation 33:

- Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI)

- Disease Activity Score (DAS)

- Disease Activity Score 28 Joints (DAS28-ESR/CRP)

- Patient-Derived DAS28

- Hospital Universitario La Princesa Index (HUPI)

- Multi-Biomarker Disease Activity Score (MBDA score, VECTRA DA)

- Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Index (RADAI)

- Rheumatoid Arthritis Disease Activity Index 5 (RADAI-5)

- Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID3)

- Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 5 (RAPID5)

- Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI)

Rheumatoid arthritis diet

With the increasing evidence of altered microbiota (gut microbiome) in the gut of rheumatoid arthritis patients being responsible for pathogenesis as well as disease progression 34, it should be desirable for doctors to advocate a supplemental “diet therapy” to rheumatoid arthritis patients. Various dietary plans for rheumatoid arthritis have been reported since 35 and are being repeatedly projected 36, such as medically supervised 7–10 days fasting 37, vegan 38 or Mediterranean diets 39. We hereby discuss the reported dietary interventions that clearly indicate clinically and statistically significant and beneficial long-term effects for relieving symptoms, delay in disease progression and associated damages in rheumatoid arthritis patients. The outcomes of published randomized clinical trials performed on rheumatoid arthritis patients to observe the effect of various dietary interventions have been summarized in Table 1. A pictorial representation of effects put by various factors on progression/remission of rheumatoid arthritis is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Factors contributing to severity of rheumatoid arthritis

Footnote: The picture summarizes various factors contributing to severity of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and diets which cause remission of symptoms (left side of image). The effects of various factors on state of disease are shown at the right side of the image. The upper half of the image shows highly inflamed joints and synovial membrane, increased infiltration of immune cells in joints on exposure to environmental factors or food antigens. Lower half of the image shows effect of various diets in reducing inflammation, immune cell infiltration, and reducing the severity of disease.

[Source 40]Table 1. Summary of clinical trials of various dietary interventions in rheumatoid arthritis (RA)

| Reference | Subjects, duration, and diet | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Kjeldsen-Kragh et al. 41 | Diet group—27 patients 7–10 days subtotal fasting (limited amount of nutritional supplements) 3.5 months on individually adjusted gluten-free vegan diet followed by lactovegetarian diet Control group—26 patients Ordinary diet throughout the study | After 1 month of diet Reduction in number of tender (p < 0.0002) and swollen joints (p < 0.04), Ritchie articular index (RAI) (p < 0.0004), pain (p < 0.0001), morning stiffness duration (p < 0.0002), grip strength, HAQ score, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) (p < 0.002), C-reactive protein (CRP) (p < 0.005), and WBC count (p < 0.0001) which were maintained even after 1 year of administration of diet Key note: Improvement can be maintained by continuing with individually adjusted diet |

| Kjeldsen-Kragh et al. 42 | Diet group—27 patients 7–10 days subtotal fasting 3.5 months on individually adjusted gluten-free vegan diet followed by lactovegetarian diet Control group—26 patients Ordinary diet throughout the study | After 1 month of treatment Significant decrease in leukocyte and platelet count (p < 0.003), IgM rheumatoid factors (p < 0.02), IgG, C3 (p < 0.04) and C4 complement components (p < 0.01), calprotectin (p < 0.03) and C3 activation products in diet responders in vegetarian diet group Key note: Dietary interventions can help in improvement of disease in some RA patients |

| Peltonen et al. 43 | Diet group—27 patients 7–10 days subtotal fasting 3.5 months on individually adjusted gluten-free vegan diet followed by 9 months lactovegetarian diet administration Control group—26 patients Ordinary diet throughout the study | Significant difference in fecal fatty acid profile at different times during the dietary intervention as compared to baseline in diet group was observed (p < 0.005). Fecal flora was significantly different between vegan diet (post 1 month treatment) and lactovegetarian diet period (p < 0.001). Significant difference in fecal flora was also observed between high improvement to low improvement groups (p < 0.001). This difference was also found at 1 month (vegan diet) and 13 months (lactovegetarian diet) Key note: Study finds association between disease activity and intestinal flora indicating impact of diet on disease progression |

| Haugen et al. 44 | Diet group—27 patients 7–10 days subtotal fasting 3.5 months on individually adjusted gluten-free vegan diet followed by lactovegetarian diet Control group—26 patients Ordinary diet throughout the study | Post 3.5 months of vegan diet Significant reduction in plasma fatty acid 20:3n-6 (p < 0.0001) and 20:4n-6 (p < 0.01) was observed which reversed to baseline concentration after lactovegetarian diet Significant reduction in 20:5n-3 post-vegan diet (p < 0.0001) and lactovegetarian diet (p < 0.01) No significant difference in fatty acid concentration between diet responders and non-responders after vegan or lactovegetarian Key note: Change in fatty acid profile could not explain disease improvement |

| Haugen et al. 45 | Diet group—17 patients 7–10 days fasting 3.5 months on gluten-free vegan diet followed by 9 months lactovegetarian diet administration Control group—17 patients Ordinary diet throughout the study | After 1 month Significant reduction in body mass index (BMI) and triceps skin fold thickness in diet group as compared with baseline (post 1 month) (p < 0.001) and controls (post study) (p = 0.04; p < 0.01) Key note: One year of dietary intervention had a minor impact on nutritional status of patients. No significant differences in other clinical variables studied were observed between the two groups |

| Kjeldsen-Kragh et al. 46 | Patients of above study were called for follow-up; 1 year post-trial. All responders and half non-responders were still on diet. Most of the patients eliminated those food which they thought aggravated their disease | Diet responders showed greatest change in clinical variables including HAQ (p < 0.04) and RAI (p < 0.02) from the baseline. Significant improvements were observed in all clinical variables including pain (p < 0.005), morning stiffness duration (p < 0.005), tender joint (p < 0.0003), RAI (p < 0.0001) and swollen joints (p < 0.05) except grip strength as compared to non-responders and controls Key note: Patients gained benefit from manipulation of diet which can be maintained for long term |

| Kjeldsen-Kragh et al. 47 | Diet group—26 RA patients 7–10 days fasting followed by 3.5 months of gluten-free vegetarian diet | Agalactosyl IgG antibodies reduced in RA patients and correlated significantly (p = 0.04) with clinical improvement post fasting which was not observed after administration of vegetarian diet Key note: IgG glycosylation may improve disease status during fasting |

| Fraser et al. 48 | Diet group—10 patients 7 days subtotal fasting 13 patients—ketogenic diet for 7 days All patients followed 2 weeks period of re-feeding on lactovegetarian diet | Post 7 days fasting Significant decrease in serum IL-6 levels in fasting group (p < 0.03) on seventh day as compared to baseline and after re-feeding. Improvement was observed in ESR, CRP, and tender joint counts post 7 days fasting Key note: Fasting improves disease activity in RA patients |

| Michalsen et al. 49 | 16 RA patients and 35 fibromyalgia patients 21 patients—vegetarian Mediterranean diet (MD) 30 patients—intermittent modified 8 days fasting therapy | No difference in the fecal bacterial counts, concentration of secretory immunoglobulin or pH of the stool within or between the two diet groups. Post 2 weeks of study, fasting RA patients showed more clinical improvement as compared to non-fasting patients Key note: Clinical improvement is not related to intestinal flora |

| Abendroth et al. 50 | 22 patients—medical fasting for 7 days 28 patient—MD | Both groups observed significant decrease in disease activity score (DAS) (p < 0.001). Significantly higher decrease in pain in fasting group on seventh day (p = 0.049). No significant difference was observed in total fatty acid profile, butyrate and propionate but acetate increased significantly (p = 0.044) in fasting group and decreased significantly in MD group. No significant correlation between diet induced changes in short chain fatty acids and disease activity changes was observed Key note: Change of intestinal microflora and relation with diet needs further studies |

| Sköldstam et al. 39 | Diet group—26 patients—MD Control group—25 patients | After 12 weeks of study, MD group showed significant reduction in DAS28 score (p < 0.001), decrease in HAQ (p = 0.020), and improvement in SF-36 health survey in two dimensions (p = 0.018). Out of 14 efficacy variables, 9 had shown improvement in diet group Key note: MD administration reduced disease activity in RA patients |

| Hafström et al. 51 | Diet group—38 patients—gluten-free vegan diet Control group—28 patients | Vegan group showed higher response rate and significant improvement in all variables except CRP. The diet responders have significant improvement in CRP (p < 0.05). Levels of IgG anti-gliadin (p = 0.0183) and anti-β-lactoglobulin (p = 0.0162) levels have significantly reduced from baselines in vegan diet groups. After 6 and 12 months, there was significant increase in Larsen score, number of erosions and joint count in both groups Key note: Diet change may reduce immunoreactivity to certain food antigens and some RA patients and may have certain clinical benefits |

| Peltonen et al. 52 | Diet group—uncooked vegan diet rich in lactobacilli Control group—normal omnivorous diet. | Diet group had significant change in fecal microflora from pre-test and post-test samples (p < 0.001) but not in control group. Significant difference was found on comparison of test group with control group at 1 month (p < 0.001). Significant difference in microflora was observed between low and high improvement index group after 1 month (p = 0.001) and after intervention (p = 0.029) but not in pre-test samples Key note: Fecal microflora changes with diet and helps in improvement of RA |

| McDougall et al. 38 | 24 RA patients—very low fat vegan diet | Significant decrease in energy intake (p < 0.001), fats (p < 0.001) and proteins (p < 0.001) and significant increase in carbohydrate intake (p < 0.001) with decrease in weight. RA symptoms decreased including pain (p < 0.004), morning stiffness (p < 0.04), joint swelling (p < 0.02), and tenderness (p < 0.01) with increased joint mobility (p < 0.001) Key note: RA symptoms significantly decrease in moderate or severe RA patients on administration of very low fat vegan diet |

| Elkan et al. 53 | Diet group—38 patients—gluten-free vegan diet Control group—28 patients | After 12 months, vegan group showed decreased BMI, LDL, and weight. DAS28 (p = 0.002) and HAQ scores (p = 0.010) decreased significantly in at least 3 months when compared to baseline and CRP decreased (p = 0.008) at 12 months. In vegan group, at least in 3 months, total cholesterol (p < 0.001), LDL (p < 0.001) and LDL/HDL ratio (p < 0.001) significantly decreased but TGs and HDL did not change. OxLDL significantly decreased (p = 0.021) after 3 months in responders group. IgM anti-phosphorylcholine increased significantly trend wise and was significant at twelfth month (p = 0.057) Key note: Vegan diet (gluten free) is anti-inflammatory and atheroprotective |

| Sköldstam et al. 54 | Study 1: Diet group—14 patients—lactovegetarian diet Control group—10 patients Study 2: 13 patients—control period of 2 months 7 patients—control period of 5 months followed by vegan diet for following 4 months Study 3: Diet group—26 patients—Cretan MD Control group—25 patients | Study 1: At end of study, diet group reported reduction in pain with a significant weight loss (p < 0.001) but no change in disease outcome and no change in control subjects were observed Study 2: During vegan diet, all 20 patients were reported to have significant reduction in pain score, increased functional capacity, and significant weight loss (p < 0.001), which was not observed during the control period Study 3: 9 out of 14 disease outcome measures were improved with a significant loss in weight (p < 0.001) and decreased pain when compared to controls Statistically significant correlation was found between diet and three disease outcome variables including ΔAcute-Phase Response (p = 0.007), ΔPain Score (p = 0.005), and ΔPhysical Function (p = 0.002) Key note: Improvement of RA on administration of Vegan, Mediterranean, or lactovegetarian diet is not related to reduction of body weight |

| Ågren et al. 55 | Diet group—16 patients—vegan diet Control group—13 patients | Significant reduction (p < 0.001) of serum total, LDL cholesterol, and phospholipid concentrations were observed in vegan diet group. Sitosterol concentration increased and that of campesterol decreased giving a significant greater ratio of sitosterol: campestrol (p < 0.001) in vegan diet group when compared to control group Key note: Serum cholesterol, cholestanol, phospholipids, and lathosterol decrease in uncooked vegan diet |

| Hänninen et al. 56 | 42 patients divided in two groups—Uncooked vegan diet for 3 months and omnivorous control groups | The RA symptoms reduced in diet group and reverted on restarting omnivorous diet. There was a significant negative correlation between degree of subjective adaptation system and decreased activity of RA (p = 0.003) Key note: Vegan diet rich in fibers, antioxidants, and lactobacilli improved RA in some patients |

| Vaghef-Mehrabany et al. 57 | Diet group—22 patients—108 colony-forming unit (CFU) of Lactobacillus casei 01 for 8 weeks 24 patients—placebo with maltodextrin for 8 weeks | Number of tender and swollen joints, serum hs-CRP levels, DAS, visual analog scale (VAS) score, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and IL-12 decreased significantly in probiotic group. Significant increase in IL-10 (p = 0.02), IL-10/IL-12 (p = 0.01), and IL-10/TNF-α (p = 0.03) was observed in the probiotic group Key note: Disease activity and inflammatory status improved in patients on L. casei 01 supplementation |

| Vaghef-Mehrabany et al. 58 | Diet group—22 patients—108 CFU of L. casei 01 for 8 weeks 24 patients—placebo with maltodextrin for 8 weeks | No significant difference was observed within or between probiotic and placebo group in serum malondialdehyde, total antioxidant capacity, and catalase activity. Erythrocyte superoxide dismutase activity decreased significantly in probiotic group and glutathione peroxidase activity decreased in both groups. Difference between two groups was insignificant for both groups at the end of the study Key note: Probiotic supplementation does not have significant effect on oxidative status of RA patients |

| Hatakka et al. 59 | Diet group—8 patients—L. rhamnosusGG (LGG) (≥5 × 109 CFU/capsule), twice a day for 12 months 13 patients—placebo group | Mean number of tender and swollen joints decreased in probiotic group. A 71% reduction in disease activity was observed in probiotic group and 30% in placebo group. Serum IL-1β increased in probiotic group and decreased in placebo group. At the end of the study, fecal recovery of LGG was increased from 25 to 86% in probiotic from baseline and decreased from 23 to 0% in placebo group Key note: More patients administered with LGG reported subjective well-being |

| Zamani et al. 60 | Diet group—30 patients—L. acidophilus (2 × 109 CFU/g), L. casei (2 × 109 CFU/g), and Bifidobacterium bifidum (2 × 109 CFU/g) 30 patients—placebo group received capsule filled with cellulose | Probiotic group observed significant decrease in DAS28 score (p = 0.01), serum insulin levels (p = 0.03), HOMA-B (p = 0.03), serum hs-CRP concentrations (p < 0.001), LDL cholesterol (p = 0.07), and total cholesterol (p = 0.09) compared to placebo group. No significant effect was observed in tender and swollen joints, VAS pain, glucose homeostasis parameters, biomarkers of oxidative stress, and lipid profiles after probiotic administration Key note: Patients had significant benefit by incorporating probiotic supplements in diet |

| Vaghef-Mehrabany et al. 61 | Diet group—22 patients—108 CFU of L. casei 01 24 patients—placebo group received similar capsules with maltodextrin | No significant difference within or between group for anthropometric and demographic parameters, physical activity was observed. Serum lipid did not change within any group significantly or in between the groups Key note: L. casei 01 could not improve serum lipid in patients |

| Alipour et al. 62 | Diet group—22 patients—108 CFU of L. casei 01 24 patients—placebo group | Probiotic decreased serum high sensitivity CRP levels (p = 0.009), counts of swollen (p = 0.003) and tender joints (p = 0.03), DAS (p < 0.05), and global health score (p = 0.00). Global health score decreased significantly in placebo group as well. At the end of study, more patients in probiotic group showed moderate response to the supplementation according to EULAR criteria but all were non-responders in placebo group. The difference of IL-6, IL-12 (0.00), TNF-α (p = 0.002), and IL-10 (p = 0.007) cytokines between the two groups was statistically significant Key note: Probiotic can be an adjunct therapy for relieving symptoms |

| de los Angeles Pineda et al. 63 | Diet group—15 patients—L. rhamnosus GR-1 and L. reuteri RC-14 with 2 billion CFU viable bacteria 14 patients—placebo | Significant difference was observed in HAQ score (p = 0.02) in probiotic group when compared to baseline but not between groups. The pro-inflammatory cytokines including GM-CSF, IL-6, IL-1α, TNF-α, and IL-15 decreased but not significantly in the probiotic group. No difference was observed in cytokine levels and DAS Key note: Probiotics did not improve RA but functional improvements were reported |

| Mandel et al. 64 | Diet group—22 patients—Bacillus coagulans GBI-30, 6086 (2 billion CFU) with green tea extract, methylsulfonylmethane, and vitamins and minerals (including vitamins A, B, C, D, E, folic acid, and selenium) 22 patients—placebo group received microcrystaline cellulose | Probiotic group showed statistically significant improvement in patient pain assessment score (p = 0.052) and pain scale (p = 0.046) as compared to baseline. Improvement was observed in patient global assessment, patient self-assessed disability, and reduction in total CRP but statistical difference was not found in physician global assessment or physician assessment of painful and swollen joints. Ability to walk 2 miles was marginally significant (p = 0.072) and ability to participate in daily activities was more in probiotic group Key note: Adjunctive therapy with probiotics serves effective for RA patients |

| Kavanagh et al. 65 | Diet group—24 patients—elemental diet 028 (E028) (4 weeks) followed by food reintroduction where food unlikely to cause intolerance were introduced first followed by those which were known to cause intolerance one at a time. Food worsening RA was eliminated 23 patients—control groups were given E028 as a substitute to any drink along with normal diet | After 4 weeks of elemental diet, the diet group showed significant increase in grip strength (p = 0.008), decrease in RAI (p = 0.006), and loss of weight as compared to control diet group. CRP concentrations were different between the two groups but not significant. Statistically significant correlation was observed between loss of weight and grip strength at 1 week (p = 0.009) and 4 weeks (p = 0.027) in the diet group Key note: Elemental diet may improve some parameters in RA patients |

| Podas et al. 66 | Diet group—21 patients—elemental diet E028 9 patients—oral prednisolone 15 mg/day | All clinical parameters of RA including early morning stiffness, VAS, RAI, and HAQ improved significantly (p < 0.05) in both groups. Clinical parameters were improved by 20% in 72% patients in elemental diet group as compared to 78% in steroid group Key note: A 2 week treatment with elemental diet is as effective as 15 mg/day of prednisolone in improvement of clinical parameters. RA may start within the intestine due to reaction to various food antigens |

| Holst-Jensen et al. 67 | Diet group—15 patients—commercial liquid diet (TU). TU contains hydrolyzed soy protein, triglycerides and carbohydrates, methionine, tryptophan, vitamins, and trace elements and is lactose free Control group—15 patients | 4 weeks of treatment caused statistical significant improvements in pain (p = 0.02), HAQ score (p = 0.03) and reduction in BMI (p = 0.001). After the study, the number of swollen joints, ESR and General assessment of health, average during the last week lowered but not statistically significant. No difference was observed in the control group. Only one patient in the diet group achieved complete remission Key note: Peptide diet can improve some subjective and objective parameters of the disease. This diet may help those patients who have diet aggravated RA |

| Van de Laar and Van der Korst 68 | Diet group—45 patients—allergen free diet 49 patients—allergen restricted with lactoproteins and yellow dyes During first 4 weeks, patients followed their normal diets followed by 4 weeks of assigned diets and then administration of normal diet for 4 weeks | No significant difference could be found in clinical effects between the allergen free and allergen restricted diet. Only 9 out of 94 patients enrolled in the study showed favorable response but the disease relapsed after readministration of usual diets Key note: Some patients have food-aggravated RA, and they can be controlled by administering allergen-free food |

| Karatay et al. 69 | 20 patients—positive skin prick test (SPT) to food extracts 20 patients—negative SPT All patients first fasted to most common allergenic food for 12 days. Food challenge was performed for PPG with allergenic food and for PNG with corn and rice for 12 days. Followed which allergenic foods were removed from respective groups | On food challenge in PPG, ESR (p < 0.05), CRP (p = 0.001), TNF-α (p < 0.01), and IL-1β (p < 0.05) increased and was also observed on re-elimination of food. In PNG, pain decreased significantly (p < 0.05) on food challenge. At end of re-elimination phase, differences were observed in between two groups in pain, duration of stiffness, number of tender and swollen joints, CRP levels, and RAI but not in HAQ and ESR levels. 72% patients in PPG group and 18% in PNG group suffered from disease aggravation on food challenge which continued in re-elimination phase Key note: Diet changes on individual level may change disease activity in patients |

Based on findings discussed in Khanna et al review 40, they have designed an anti-inflammatory food chart (Table 2) that may aid in reducing signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. This may not cure the patients; however, an effective incorporation of these food items in the daily food plan may help to reduce their disease activity, delay disease progression, and reduce joint damage, and eventually a decreased dose of drugs administered for therapeutic treatment of patients. The believe that an ideal meal can include raw or moderately cooked vegetables (lots of greens, legumes), with addition of spices like turmeric and ginger 70, seasonal fruits 71, probiotic yogurt 72; all of which are good sources of natural antioxidants and deliver anti-inflammatory effects. The patient should avoid any processed food, high salt 73, oils, butter, sugar, and animal products 74. Dietary supplements like vitamin D 75, cod liver oil 76, and multivitamins 77 can also help in managing rheumatoid arthritis. This diet therapy with low impact aerobic exercises can be used for a better degree of self-management of rheumatoid arthritis with minimal financial burden 78. A better patient compliance is, however, always necessary for effective care and management of rheumatoid arthritis.

Table 2. Recommended anti-inflammatory food chart

| Fruits | Dried plums, grapefruits, grapes, blueberries, pomegranate, mango (seasonal fruit), banana, peaches, apples |

| Cereals | Whole oatmeal, whole wheat bread, whole flattened rice |

| Legumes | Black soybean, black gram |

| Whole grains | Wheat, rice, oats, corn, rye, barley, millets, sorghum, canary seed |

| Spices | Ginger, turmeric |

| Herbs | Sallaki, ashwagandha |

| Oils | Olive oil, fish oil, borage seed oil (in encapsulated form) |

| Miscellaneous | Yogurt (curd), green tea, basil (tulsi) tea |

Rheumatoid arthritis treatment

Although there is no cure for rheumatoid arthritis, treatment can:

- Relieve pain and swelling

- Slow down or stop joint damage

- Help lower the number of symptom “flareups” (times when pain or swelling is the worst)

- Improve your ability to do daily activities such as bathing, getting dressed, doing chores, reaching, and lifting.

Although there’s no cure for rheumatoid arthritis, early treatment and support (including medicine, lifestyle changes, supportive treatments and surgery) can reduce the risk of joint damage and limit the impact of rheumatoid arthritis.

The International Task Force Guidelines published in 2014 make the following recommendations regarding treatment of rheumatoid arthritis 79:

- The primary goal of treatment is to achieve long-term clinical remission and optimize quality of life with the absence of signs and symptoms associated with inflammatory disease activity.

- If clinical remission cannot be achieved, low disease activity is an acceptable alternative.

- Disease activity should be assessed every month in patients with moderate to severe disease activity.

- In patients with low disease activity or clinical remission, disease activity should be assessed every 3 to 6 months.

Clinical studies indicate that remission of symptoms is more likely when treatment begins early with medications known as disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs).

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) typically used in treating rheumatoid arthritis include methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, sulfasalazine, and leflunomide. Anti-TNF-alpha agents include etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab pegol. Non-TNF biologic DMARDs include interleukin (IL) 6 receptor antagonists such as tocilizumab and sarilumab, T-cell blockers such as abatacept (CTLA4-Ig), and the anti-CD20 B-cell depleting monoclonal antibody such as rituximab. Other synthetic DMARDs include Janus kinases (JAK) inhibitors such as tofacitinib, baricitinib, and upadacitinib.

DMARD therapy, including biologic agents and targeted therapy agents (tofacitinib), should be temporarily held in patients with a serious active infection. They can be resumed after the infection has resolved and antimicrobial treatment has been completed 14. It is essential to remember that all patients starting treatment for rheumatoid arthritis should be screened for hepatitis B and C and tuberculosis. Methotrexate should be avoided in patients with liver damage 14. Patients with latent tuberculosis should complete treatment for at least one month before the initiation of biologic agents. If patients cannot take or complete treatment for latent tuberculosis, conventional DMARD therapy should be used 14. In patients with underlying skin cancer and lymphoproliferative disorders, biologic agents should be avoided except for rituximab in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders as there is evidence of benefit from B-cell suppression in these cases 14. The American College of Rheumatology also recommends that before starting therapy for rheumatoid arthritis, patients should receive vaccination for pneumococcus, hepatitis, influenza, human papillomavirus (HPV), and herpes zoster virus (HZV).

American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism Treatment Guidelines for Rheumatoid Arthritis

American College of Rheumatology and the European League Against Rheumatism Treatment Guidelines 14:

- According to the American College of Rheumatology treatment guidelines for early rheumatoid arthritis, patients who have not taken disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) therapy should start DMARD therapy regardless of the activity level.

- In patients with low disease activity and early disease, monotherapy with methotrexate is the preferred treatment.

- Leflunomide or sulfasalazine are the first-line treatment in patients with a contraindication to methotrexate or intolerance to it.

- If monotherapy with DMARD does not control disease activity (regardless of concomitant glucocorticoid use), therapy should be altered. Methotrexate can be continued or discontinued at this point. Additional therapy options after failed monotherapy with DMARD are recommended as either dual traditional/nonbiologic DMARD therapy, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, or non-tumor necrosis factor biologic agents.

- In patients with established rheumatoid arthritis, who are DMARD naive, methotrexate is the preferred agent for initial monotherapy, regardless of the disease activity level.

- If monotherapy with DMARD does not control disease activity in established rheumatoid arthritis (regardless of concomitant glucocorticoid use), dual DMARD therapy, a TNF inhibitor, a non-TNF biologic agent, or tofacitinib therapy can be added.

- If disease activity remains high on TNF inhibitor monotherapy, DMARD therapy should be added in addition to the TNF inhibitor.

- If disease activity remains high despite anti-TNF inhibitor switch to a non-TNF biologic agent with or without methotrexate

- If disease activity remains high despite a trial of anti-TNF and non-TNF agents, use another non-TNF biologic agent before considering tofacitinib.

- If still uncontrolled despite the above trials, use tofacitinib

- If disease activity remains high despite the above combination therapies, short-term low-dose glucocorticoid therapy should be added.

- TNF inhibitors should be avoided in patients with congestive heart failure.

- Patients with hepatitis C who have not been treated or are currently not on treatment for it should receive nonbiologic DMARD therapy rather than TNF inhibitors.

Rheumatoid arthritis medications

The types of medications recommended by your doctor will depend on the severity of your symptoms and how long you’ve had rheumatoid arthritis.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or cyclo-oxygenase-2 selective (COX-2) inhibitors. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can relieve pain and reduce inflammation. Over-the-counter NSAIDs include ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB) and naproxen sodium (Aleve). Stronger NSAIDs are available by prescription. Side effects may include ringing in your ears, stomach irritation, heart problems, and liver and kidney damage.

- Steroids. Corticosteroid medications, such as prednisone, reduce inflammation and pain and slow joint damage. Side effects may include thinning of bones, weight gain and diabetes. Doctors often prescribe a corticosteroid to relieve acute symptoms, with the goal of gradually tapering off the medication.

- Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). These drugs can slow the progression of rheumatoid arthritis and save the joints and other tissues from permanent damage. Common DMARDs include methotrexate (Trexall, Otrexup, Rasuvo), leflunomide (Arava), hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) and sulfasalazine (Azulfidine). Side effects vary but may include liver damage and severe lung infections.

- Biologic agents also known as biologic response modifiers, this newer class of DMARDs includes abatacept (Orencia), adalimumab (Humira), anakinra (Kineret), certolizumab (Cimzia), etanercept (Enbrel), golimumab (Simponi), infliximab (Remicade), rituximab (Rituxan), sarilumab (Kevzara) and tocilizumab (Actemra). Biologic DMARDs are usually most effective when paired with a conventional DMARD, such as methotrexate. This type of drug also increases the risk of infections.

- Targeted synthetic DMARDs also known as JAK inhibitors. Baricitinib (Olumiant), tofacitinib (Xeljanz) and upadacitinib (Rinvoq) may be used if conventional DMARDs and biologics haven’t been effective. Higher doses of tofacitinib can increase the risk of blood clots in the lungs, serious heart-related events and cancer.

Sometimes DMARDs and corticosteroids are taken together to treat rheumatoid arthritis.

What are DMARDs?

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are a family of medicines that stop your body’s immune system from attacking and destroying joints. If you have severe rheumatoid arthritis symptoms or are not getting enough relief from pain relievers or corticosteroids, your doctor may suggest a disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD). Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs)s may be taken with each other or together with pain relievers and corticosteroids.

There are two kinds of Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs): nonbiologic and biologic.

Nonbiologic Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

Like most medicines, nonbiologic DMARDs are produced from chemicals. They are usually taken daily or weekly as pills, but some can also be given as shots. Nonbiologic DMARDs include:

- Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil®)

- Leflunomide (Arava®)

- Methotrexate (Folex®, Rheumatrex®, Trexall®)

- Sulfasalazine (Azulfidine EN-Tabs®, Sulfazine®)

What does research say about nonbiologic DMARDs?

How well they work to treat rheumatoid arthritis:

- Methotrexate (Folex®, Rheumatrex®, Trexall®) and sulfasalazine (Azulfidine EN-Tabs®, Sulfazine®) work about the same to reduce symptoms, reduce the number of joints affected, improve the ability to do daily activities, and slow down or stop joint damage.

- Leflunomide (Arava®) appears to work about as well as methotrexate, but there is not enough research to know this for certain.

Side effects:

- All nonbiologic DMARDs appear to cause about the same amount of side effects, but there is not enough research to know this for certain.

Biologic Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

Biologic agents also known as biologic response modifiers, this newer class of DMARDs includes abatacept (Orencia), adalimumab (Humira), anakinra (Kineret), certolizumab (Cimzia), etanercept (Enbrel), golimumab (Simponi), infliximab (Remicade), rituximab (Rituxan), tocilizumab (Actemra) and tofacitinib (Xeljanz).

These drugs can target parts of the immune system that trigger inflammation that causes joint and tissue damage. These types of drugs also increase the risk of infections.

Biologic DMARDs are usually most effective when paired with a nonbiologic DMARD, such as methotrexate.

Biologic DMARDs are proteins similar to those made in your body, but these proteins are created in laboratories. Biologic DMARDs must be given as shots or through an IV (intravenous) tube into a vein in your arm. Biologic DMARDs include:

- Abatacept (Orencia®)

- Adalimumab (Humira®)

- Anakinra (Kineret®)

- Certolizumab pegol (Cimzia®)

- Etanercept (Enbrel®)

- Golimumab (Simponi®)

- Infliximab (Remicade®)

- Rituximab (Rituxan®)

- Tocilizumab (Actemra®)

Some biologic DMARDs such as infliximab (Remicade®), rituximab (Rituxan®), and tocilizumab (Actemra®) must be given through an IV tube at a doctor’s office or clinic. This could take up to 2 hours. Other biologic DMARDs come in injection pens that you can use at home.

Most biologic DMARDs are given once a month, once every other week, or once a week. Your doctor may change your schedule depending on how well you are doing.

Side effects vary but may include liver damage, bone marrow suppression and severe lung infections.

What does research say about biologic DMARDs?

How well they work to treat rheumatoid arthritis:

- Biologic DMARDS work to decrease or completely stop symptoms, improve the ability to do daily activities, and slow down or stop joint damage.

Side effects:

- Taking a biologic DMARD increases the risk of developing serious infections.

- Taking biologic DMARDs for long periods of time does not increase the risk of having serious side effects.

What does research say about how nonbiologic and biologic DMARDs compare to each other ?

How well they work to treat rheumatoid arthritis:

- The biologic DMARDs adalimumab (Humira®) and etanercept (Enbrel®) help decrease symptoms about the same as the nonbiologic DMARD methotrexate.

Side effects:

- There is not enough research to know if certain side effects happen more often with nonbiologic or biologic DMARDs.

Table 3. Possible Side Effects of Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

| Nonbiologic DMARDs | Biologic DMARDs |

|---|---|

| Upset stomach Nausea Diarrhea Hair loss Mouth sores Rash or serious skin reactions Liver, kidney, or lung problems | Redness, swelling, itching, bruising, or pain in the area where the shot was given Sinus infection (sore throat, runny nose, hoarseness) Headache Nausea Diarrhea |

| Possible Serious Side Effects | |

| In rare cases, the nonbiologic DMARD methotrexate and some biologic DMARDs (including adalimumab [Humira®], etanercept [Enbrel®], golimumab [Simponi®], and infliximab [Remicade®]) have been associated with: Serious infections such as tuberculosis (called “TB”), fungal infections such as yeast, pneumonia, or food-borne illnesses such as listeria Cancer, usually lymphoma (cancer in the lymph glands, which are part of the immune system) The risk of serious infections or cancer is increased by taking two or more biologic DMARDs together or by taking a biologic DMARD with a nonbiologic DMARD. The exact risk to people with RA who are taking a DMARD is not known. Rituximab (Rituxan®) can cause a severe reaction the first time you take it. It could also cause a life-threatening rash. | |

What are corticosteroids?

Corticosteroids are a kind of medicine that works like a certain type of hormone in your body. Corticosteroids can help reduce swelling and stop the body’s immune system from attacking healthy joints. Corticosteroids are taken as pills, liquids, or shots and include:

- Methylprednisolone (Depo Medrol®, Medrol®, Solu-Medrol®)

- Prednisolone (Delta-Cortef ®, Econopred®, Orapred®, Pediapred®, Prelone®)

- Prednisone (Liquidpred®, Deltasone®, Sterapred®)

What are the possible side effects of corticosteroids?

Possible side effects of corticosteroids listed by the FDA include:

- Swelling in the lower legs

- Weight gain

- Increased blood pressure

- Mood swings

- Increased pressure in the eyes

Possible side effects from taking corticosteroids for longer than a few days or weeks include:

- High blood sugar, which can cause or worsen diabetes

- Increased risk of infections

- Loss of calcium from bones, which can make it easier to break a bone

- Irregular menstrual periods

- Thin skin that bruises easily

- Longer time for wounds to heal.

What does research say about combining medicines?

How well they work to treat rheumatoid arthritis:

- If treatment with one DMARD does not relieve symptoms, taking a biologic DMARD together with the nonbiologic DMARD methotrexate works better than taking only one to improve the ability to do daily activities and slow down or stop joint damage.

- Adding a corticosteroid to treatment with a nonbiologic DMARD improves the ability to do daily activities more than taking a nonbiologic DMARD alone.

- Adding a corticosteroid may also slow down or stop joint damage more than taking a nonbiologic DMARD alone, but there is not enough research to know this for certain.

- For people who have had rheumatoid arthritis for less than 3 years, taking two or three nonbiologic DMARDs plus a corticosteroid works better than taking only one nonbiologic DMARD.

- For people who have had rheumatoid arthritis for less than 3 years, taking the nonbiologic DMARD methotrexate together with a biologic DMARD decreases or completely stops symptoms and slows down or stops joint damage in people whose rheumatoid arthritis was quickly getting worse.

- For people who have had rheumatoid arthritis for a long time without any improvement, taking three nonbiologic DMARDs together reduces symptoms and the number of joints affected more than taking one or two nonbiologic DMARDs.

Side effects:

- Taking a nonbiologic DMARD with a biologic DMARD does not cause more side effects than taking the biologic DMARD alone.

- Taking two or more biologic DMARDs together can cause more serious side effects than taking only one.

- Taking a corticosteroid together with a nonbiologic DMARD does not make treatment more difficult to tolerate.

- In people who have had RA for less than 3 years, taking two or three nonbiologic DMARDs plus a corticosteroid does not make treatment more difficult to tolerate than taking only a nonbiologic DMARD.

What should you think about when deciding which medicine is right for you?

More research is needed to know which rheumatoid arthritis medicines might work best for different people. There are several things to consider when choosing a medicine to treat your rheumatoid arthritis:

- The trade-offs between the possible benefits and side effects for each medicine

- Which medicine best fits your lifestyle, what is important to you (your values), and your preferences

- You may want to think about how comfortable you are with taking pills, getting shots, or taking the medicine through an IV tube. You may also want to consider how often you are able to go to the doctor’s office or clinic and how much time you are able to spend there.

- The cost of each medicine

What are the trade-offs ?

Only you and your doctor can decide whether taking a DMARD for your rheumatoid arthritis is worth the risk of possible side effects. You and your doctor should discuss:

- The amount of pain or joint damage you have and whether treatment with a DMARD can help

- The risk of serious side effects from DMARDs

- Signs to look for to help you notice serious side effects so they can be treated or so your medicine can be changed

- Whether adding a corticosteroid to your treatment with DMARDs might help

- Other options besides DMARDs that might help your rheumatoid arthritis

What are the costs of rheumatoid arthritis medications?

The costs to you for nonbiologic and biologic DMARDs and corticosteroids depend on:

- Your health insurance plan

- The amount (dose) you need

- Whether you take the medicine as a pill, as a shot, or through an IV tube

- Whether a generic form of the medicine is available

- Whether the company that makes the medicine offers financial help to lower the cost

Corticosteroids can be taken for short periods of time (30 days) or longer, depending on your specific needs. The cost for corticosteroids is around $3 to $15 a month. The cost to you depends on how much of the medicine you need and how long you will need to take it.

Table 4. Wholesale Prices: Nonbiologic and Biologic DMARDs

| Drug Name | Brand Name | Price per Month* | Form | Dose |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonbiologic DMARDs | ||||

| Hydroxychloroquine | Generic | $35–$75 | Tablet | 200–400 mg daily |

| Plaquenil® | $110–$215 | |||

| Leflunomide | Generic | $490.00 | Tablet | 20 mg daily |

| Arava® | $910.00 | |||

| Methotrexate | Generic | $45–$90 | Tablet | 7.5–15 mg weekly |

| Folex®, Rheumatrex®, Trexall® | $125–$140 | |||

| Sulfasalazine | Generic | $40.00 | Tablet | 2,000 mg daily |

| Azulfidine EN-Tabs® | $120.00 | |||

| Sulfazine® | $30.00 | |||

| Biologic DMARDs(Generic versions of these medicines are not available.) | ||||

| Abatacept | Orencia® | $1,430–$2,860 | IV | 500–1,000 mg monthly |

| $2,530.00 | Shot | 125 mg weekly | ||

| Adalimumab | Humira® | $2,450.00 | Shot | 40 mg twice a month |

| Anakinra | Kineret® | $2,760.00 | Shot | 100 mg daily |

| Certolizumab pegol | Cimzia® | $2,360.00 | Shot | 400 mg monthly |

| Etanercept | Enbrel® | $2,475.00 | Shot | 50 mg weekly |

| Golimumab | Simponi® | $2,650.00 | Shot | 50 mg monthly |

| Infliximab | Remicade® | $3,725–$9,300 | IV | 200–500 mg twice a month (depending on your weight) |

| Rituximab | Rituxan® | $15,180.00 | IV | 1,000 mg twice a month |

| Tocilizumab | Actemra® | $1,660–$3,320 | IV | 400–800 mg monthly (depending on your weight) |

Ask your doctor

- Do you think a DMARD could help my rheumatoid arthritis ?

- What serious side effects should I look for?

- Would adding a corticosteroid to a DMARD help my rheumatoid arthritis ?

- How long will it take until I start to feel better?

- Is there a less expensive medicine that I could take?

- What else can I do to help my rheumatoid arthritis ?

- Are there specific lifestyle changes you can suggest that might help?

Physical and Occupational Therapy

Your doctor may send you to a physical or occupational therapist who can teach you exercises to help keep your joints flexible. The therapist may also suggest new ways to do daily tasks, which will be easier on your joints. For example, if your fingers are sore, you may want to pick up an object using your forearms.

Assistive devices can make it easier to avoid stressing your painful joints. For instance, a kitchen knife equipped with a saw handle helps protect your finger and wrist joints. Certain tools, such as buttonhooks, can make it easier to get dressed. Catalogs and medical supply stores are good places to look for ideas.

Surgery

If medications fail to prevent or slow joint damage, you and your doctor may consider surgery to repair damaged joints. Surgery may help restore your ability to use your joint. It can also reduce pain and correct deformities.

Rheumatoid arthritis surgery may involve one or more of the following procedures:

- Synovectomy. Surgery to remove the inflamed synovium (lining of the joint). Synovectomy can be performed on knees, elbows, wrists, fingers and hips.

- Tendon repair. Inflammation and joint damage may cause tendons around your joint to loosen or rupture. Your surgeon may be able to repair the tendons around your joint.

- Joint fusion. Surgically fusing a joint may be recommended to stabilize or realign a joint and for pain relief when a joint replacement isn’t an option.

- Total joint replacement. During joint replacement surgery, your surgeon removes the damaged parts of your joint and inserts a prosthesis made of metal and plastic.

Surgery carries a risk of bleeding, infection and pain. Discuss the benefits and risks with your doctor.

Lifestyle and home remedies for rheumatoid arthritis

You can take steps to care for your body if you have rheumatoid arthritis. These self-care measures, when used along with your rheumatoid arthritis medications, can help you manage your signs and symptoms:

- Exercise regularly. Gentle exercise can help strengthen the muscles around your joints, and it can help fight fatigue you might feel. Check with your doctor before you start exercising. If you’re just getting started, begin by taking a walk. Try swimming or gentle water aerobics. Avoid exercising tender, injured or severely inflamed joints.

- Apply heat or cold. Heat can help ease your pain and relax tense, painful muscles. Cold may dull the sensation of pain. Cold also has a numbing effect and decreases muscle spasms.

- Relax. Find ways to cope with pain by reducing stress in your life. Techniques such as guided imagery, distraction and muscle relaxation can all be used to control pain.

Alternative medicine

Some common complementary and alternative treatments that have shown promise for rheumatoid arthritis include:

- Fish oil. Some preliminary studies have found that fish oil supplements may reduce rheumatoid arthritis pain and stiffness. Side effects can include nausea, belching and a fishy taste in the mouth. Fish oil can interfere with medications, so check with your doctor first.

- Plant oils. The seeds of evening primrose, borage and black currant contain a type of fatty acid that may help with rheumatoid arthritis pain and morning stiffness. Side effects may include nausea, diarrhea and gas. Some plant oils can cause liver damage or interfere with medications, so check with your doctor first.

- Tai chi. This movement therapy involves gentle exercises and stretches combined with deep breathing. Many people use tai chi to relieve stress in their lives. Small studies have found that tai chi may reduce rheumatoid arthritis pain. When led by a knowledgeable instructor, tai chi is safe. But don’t do any moves that cause pain.

Coping and support

The pain and disability associated with rheumatoid arthritis can affect a person’s work and family life. Depression and anxiety are common, as are feelings of helplessness and low self-esteem.

The degree to which rheumatoid arthritis affects your daily activities depends in part on how well you cope with the disease. Talk to your doctor or nurse about strategies for coping. With time you’ll learn what strategies work best for you. In the meantime, try to:

- Take control. With your doctor, make a plan for managing your arthritis. This will help you feel in charge of your disease.

- Know your limits. Rest when you’re tired. Rheumatoid arthritis can make you prone to fatigue and muscle weakness. A rest or short nap that doesn’t interfere with nighttime sleep may help.

- Connect with others. Keep your family aware of how you’re feeling. They may be worried about you but might not feel comfortable asking about your pain.

- Find a family member or friend you can talk to when you’re feeling especially overwhelmed. Also connect with other people who have rheumatoid arthritis — whether through a support group in your community or online.

- Take time for yourself. It’s easy to get busy and not take time for yourself. Find time for what you like, whether it’s time to write in a journal, go for a walk or listen to music. Use this time to relieve stress and reflect on your feelings.

Rheumatoid arthritis prognosis