Stercoral ulcer

Stercoral ulcer is an ulcer produced by pressure necrosis of the bowel wall from a hard fecal mass that occurs most commonly as an isolated lesion in the rectum and sigmoid colon along the antimesenteric margin 1. This pattern is thought to be caused by harder consistency of the stool, relatively poor blood supply, a narrow diameter and high intraluminal pressure in this location 2. Stercoral ulcer usually occurs in elderly patients with a history of chronic constipation. Although the principal complications of stercoral ulceration include perforation and hemorrhage, there have been few reports of lower gastrointestinal bleeding related to the lesion 3. The prevalence of stercoral ulcer is unknown. In autopsy studies, stercoral ulcer has been found in 1.3%–5.7% of elderly patients in long-term care facilities 4.

Constipation typically is defined as having fewer than three bowel movements a week or other symptoms (e.g., hard stools, excessive straining, or a sense of incomplete evacuation after defecation). Chronic constipation refers to these symptoms when they last for several weeks or longer.

Stercoral ulcer typical risk factors are chronic constipation, age >60, female sex, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) 5, heroin addiction 6, antacids, steroids, amitriptyline, and other constipating agents 7. Stercoral ulcer has also been reported in patients receiving dialysis 7, patients on immunosuppressive therapy after kidney transplant 8, and those with spinal cord injury 9:1054–1058.)).

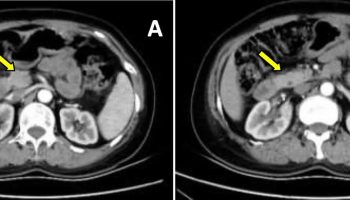

Stercoral ulcer perforation of the colon is a rare life-threatening surgical condition 10. Stercoral ulcer perforation is associated with a mortality rate of 35%. Stercoral ulcer perforation commonly occurs in the sigmoid colon (50%) and rectosigmoid junction (24%) 5. Stercoral ulcer perforation should be suspected in elderly and in anyone with a history of constipation with unexplained abdominal pain and investigated appropriately with a CT scan to allow timely and optimal treatment. Typical pathologic findings include areas of ischemic necrosis surrounded by nonspecific inflammatory changes 11. Since its first description in 1894 12, there have been about 150 cases reported in the literature 13. In one case series, it accounted for 3.2% of all colonic perforations 11.

Vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors (VEGFIs) such as bevacizumab, sorafenib, sunitinib, and pazopanib are associated with vascular-related side effects such as gastrointestinal (GI) ulceration and/or perforation. A 1–2% risk of gastrointestinal perforation with these agents has been described 14. Stercoral ulcer perforation was reported in a patient with opioid-induced constipation receiving intravenous chemotherapy regimen for advanced stomach cancer 15.

Stercoral ulcer causes

Stercoral ulcer typical risk factors are chronic constipation, age >60, female sex, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) 5, heroin addiction 6, antacids, steroids, amitriptyline, and other constipating agents 7. Stercoral ulcer has also been reported in patients receiving dialysis 7, patients on immunosuppressive therapy after kidney transplant 8, and those with spinal cord injury 9:1054–1058.)).

Vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors (VEGFIs) such as bevacizumab, sorafenib, sunitinib, and pazopanib are associated with vascular-related side effects such as gastrointestinal (GI) ulceration and/or perforation. A 1–2% risk of gastrointestinal perforation with these agents has been described 14. Stercoral ulcer perforation was reported in a patient with opioid-induced constipation receiving intravenous chemotherapy regimen for advanced stomach cancer 15.

Stercoral ulcer symptoms

Stercoral ulcer usually occurs in elderly patients with a history of chronic constipation. Although the principal complications of stercoral ulceration include perforation and hemorrhage, there have been few reports of lower gastrointestinal bleeding related to the lesion 3.

Constipation typically is defined as having fewer than three bowel movements a week or other symptoms (e.g., hard stools, excessive straining, or a sense of incomplete evacuation after defecation). Chronic constipation refers to these symptoms when they last for several weeks or longer.

Signs and symptoms of chronic constipation include:

- Passing fewer than three stools a week

- Having lumpy or hard stools

- Straining to have bowel movements

- Feeling as though there’s a blockage in your rectum that prevents bowel movements

- Feeling as though you can’t completely empty the stool from your rectum

- Needing help to empty your rectum, such as using your hands to press on your abdomen and using a finger to remove stool from your rectum

Constipation may be considered chronic if you’ve experienced two or more of these symptoms for the last three months.

Stercoral ulcer diagnosis

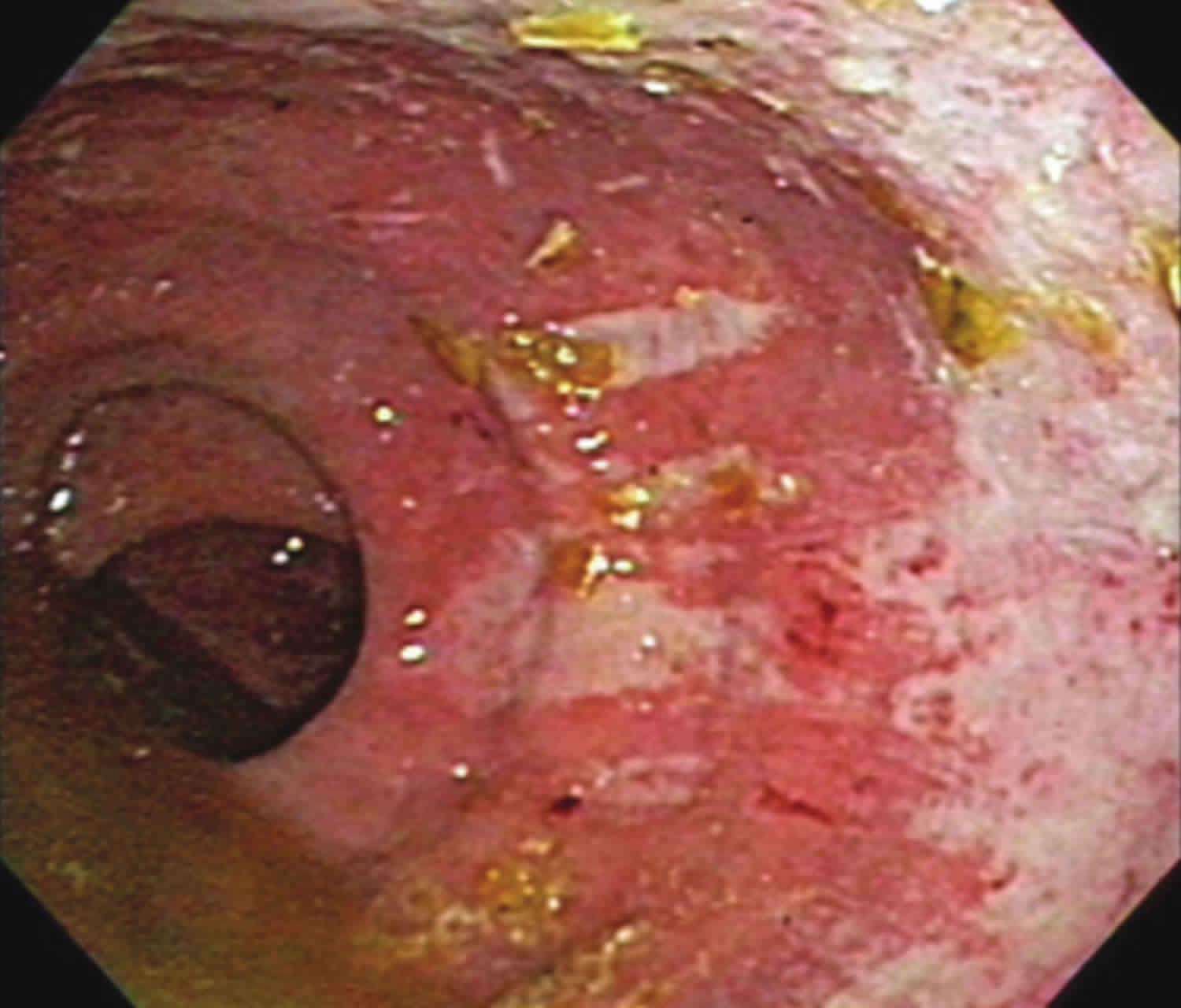

The diagnosis of nonperforating stercoral ulcer is usually based on the endoscopic finding of an irregular, geographically outlined ulcer that conforms to the contour of the impacted feces.

Stercoral ulcer treatment

Bleeding from stercoral ulcers has been successfully treated with endoscopic hemostasis, including endoscopic multipolar electrocoagulation and injection therapy 16. Surgical intervention is indicated if stercoral perforation or failure to control bleeding is encountered.

References- Massive hematochezia from a visible vessel within a stercoral ulcer: effective endoscopic therapy. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Volume 46, Issue 4, October 1997, Pages 369-370 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0016-5107(97)70130-5

- Huang CC, Wang IF, Chiu HH. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding caused by stercoral ulcer. CMAJ. 2011;183(2):E134. doi:10.1503/cmaj.100621 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3033957

- Huang, C. C., Wang, I. F., & Chiu, H. H. (2011). Lower gastrointestinal bleeding caused by stercoral ulcer. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne, 183(2), E134. doi:10.1503/cmaj.100621 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3033957

- Madan P, Bhayana S, Chandra P, et al. Lower gastrointestinal bleeding: associated with Sevelamer use. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:2615–6

- Chakravartty S, Chang A, Nunoo-Mensah J. A systematic review of stercoral perforation. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:930–935.

- Hollingworth J, Alexander-Williams J. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and stercoral perforation of the colon. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1991;73:337–339. discussion 339–340.

- Velitchkov N, et al. Stercoral perforation of the normal colon: report of five cases. Sao Paulo Med J. 1996;114:1317–1323.

- Aguilo JJ, et al. Intestinal perforation due to fecal impaction after renal transplantation. J Urol. 1976;116:153–155.

- Gekas P, Schuster MM. Stercoral perforation of the colon: case report and review of the literature. Gastroenterology. 1981;80((Pt 1

- Mouchli MA, Meehan AM. Stercoral Ulcer-Associated Perforation and Chemotherapy. Case Rep Oncol. 2017;10(2):442–446. Published 2017 May 16. doi:10.1159/000475756 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5597916

- Maurer CA, et al. Use of accurate diagnostic criteria may increase incidence of stercoral perforation of the colon. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:991–998.

- Berry J. Dilatation and rupture of the sigmoid flexure. BMJ 1894;1:301

- Gough AE, et al. Perforated stercoral ulcer: a 10-year experience. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64:912–914.

- Barney BM, et al. Increased bowel toxicity in patients treated with a vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor (VEGFI) after stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;87:73–80.

- Kang J, Chung M. A stercoral perforation of the descending colon. J Korean Surg Soc. 2012;82:125–127.

- Matsushita M, Hajiro K, Takakuwa H, et al. Bleeding stercoral ulcer with visible vessels: effective endoscopic injection therapy without electrocoagulation. Gastrointest Endosc 1998;48:559.