Bronchorrhea

Bronchorrhea is arbitrarily defined as the production of more than 100 mL of watery sputum per day 1. Bronchorrhea is typically associated with malignancy, specifically bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma now called adenocarcinoma in situ, which is an uncommon subset of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and pulmonary metastases 2. The bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma is a subtype of pulmonary adenocarcinoma, which is further subdivided into mucinous, nonmucinous, and an intermediate form 2. The mucinous form arises from mucinous metaplasia of bronchiolar cells and is associated with mucosecretion. Rates of bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma are increasing and it accounts for 3–9% of new lung cancer diagnoses, of which 20–25% are the mucinous form 3. Although uncommon, bronchorrhea also is associated with nonmalignant processes such as chronic bronchitis, asthma, tuberculosis, and scorpion stings 2.

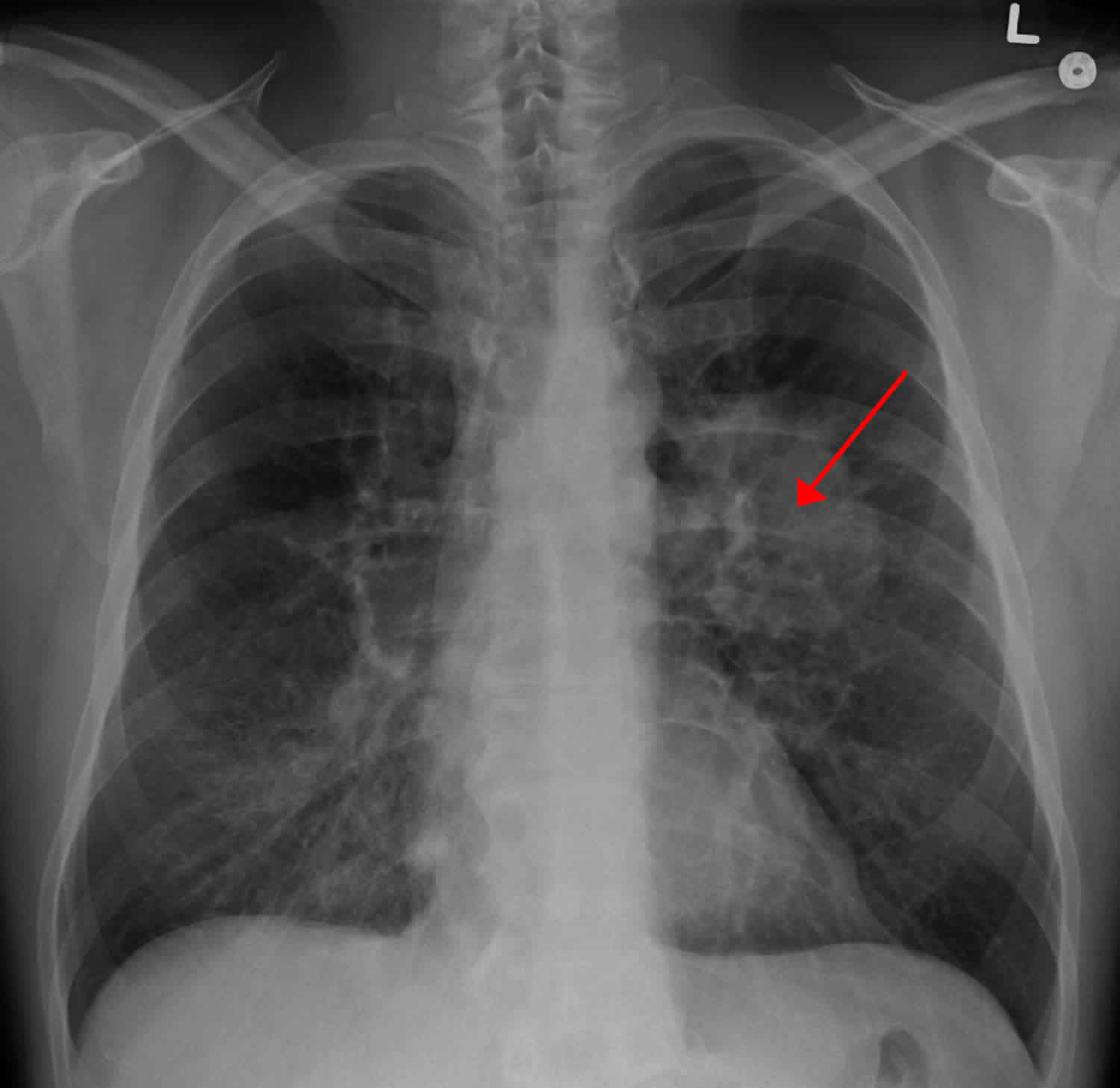

Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (adenocarcinoma in situ) develops from terminal bronchiolar and acinar epithelia, growing along alveolar septa but without evidence of vascular or pleural involvement. A final diagnosis of bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma can only be achieved from a surgical specimen.

Excess sputum production in patients with bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma is thought to be caused by a few different mechanisms. First, inflammatory stimuli are thought to cause hypersecretion of mucous glycoprotein. Takeyama et al. 4 suggested linkage to an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway in which stimulation of epidermal growth factor receptor causes MUC5AC expression in airway epithelial cells in vivo and in vitro. The MUC5AC is a major component of the mucus matrix forming a family of mucins in the airways 5. Bronchorrhea also is thought to be caused by increased trans-epithelial chloride secretion, which in turn is associated with the excretion of water. Finally, it is thought to be related to excessive transudation of plasma products into airways 6. The true incidence of bronchorrhea in patients with bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma is not known; but one review found that it occurs in 6% of the cases 7.

Bronchorrhea causes

Bronchorrhea is typically associated with malignancy, specifically bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma (now called adenocarcinoma in situ, which is an uncommon subset of non-small cell lung cancer [NSCLC]) and pulmonary metastases 2. The bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma is a subtype of pulmonary adenocarcinoma, which is further subdivided into mucinous, nonmucinous, and an intermediate form 2. The mucinous form arises from mucinous metaplasia of bronchiolar cells and is associated with mucosecretion. Rates of bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma are increasing and it accounts for 3–9% of new lung cancer diagnoses, of which 20–25% are the mucinous form 3. Although uncommon, bronchorrhea also is associated with nonmalignant processes such as chronic bronchitis, asthma, tuberculosis, and scorpion stings 2.

Bronchorrhea symptoms

Bronchorrhea is arbitrarily defined as the production of more than 100 mL of watery sputum per day 1. Bronchorrhea is typically associated with malignancy, specifically bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma (now called adenocarcinoma in situ, which is an uncommon subset of non-small cell lung cancer [NSCLC]) and pulmonary metastases 2. The bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma is a subtype of pulmonary adenocarcinoma, which is further subdivided into mucinous, nonmucinous, and an intermediate form 2. The mucinous form arises from mucinous metaplasia of bronchiolar cells and is associated with mucosecretion. Rates of bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma are increasing and it accounts for 3–9% of new lung cancer diagnoses, of which 20–25% are the mucinous form 3. Although uncommon, bronchorrhea also is associated with nonmalignant processes such as chronic bronchitis, asthma, tuberculosis, and scorpion stings 2.

Signs and symptoms of lung cancer

Most lung cancers do not cause any symptoms until they have spread, but some people with early lung cancer do have symptoms. If you go to your doctor when you first notice symptoms, your cancer might be diagnosed at an earlier stage, when treatment is more likely to be effective.

Most of these symptoms are more likely to be caused by something other than lung cancer. Still, if you have any of these problems, it’s important to see your doctor right away so the cause can be found and treated, if needed.

The most common symptoms of lung cancer are:

- A cough that does not go away or gets worse

- Coughing up blood or rust-colored sputum (spit or phlegm)

- Chest pain that is often worse with deep breathing, coughing, or laughing

- Hoarseness

- Loss of appetite

- Unexplained weight loss

- Shortness of breath

- Feeling tired or weak

- Infections such as bronchitis and pneumonia that don’t go away or keep coming back

- New onset of wheezing

If lung cancer spreads to other parts of the body, it may cause:

- Bone pain (like pain in the back or hips)

- Nervous system changes (such as headache, weakness or numbness of an arm or leg, dizziness, balance problems, or seizures), from cancer spread to the brain

- Yellowing of the skin and eyes (jaundice), from cancer spread to the liver

- Swelling of lymph nodes (collection of immune system cells) such as those in the neck or above the collarbone

Some lung cancers can cause syndromes, which are groups of specific symptoms.

Horner syndrome

Cancers of the upper part of the lungs are sometimes called Pancoast tumors. These tumors are more likely to be non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) than small cell lung cancer (SCLC).

Pancoast tumors can affect certain nerves to the eye and part of the face, causing a group of symptoms called Horner syndrome:

- Drooping or weakness of one upper eyelid

- A smaller pupil (dark part in the center of the eye) in the same eye

- Little or no sweating on the same side of the face

Pancoast tumors can also sometimes cause severe shoulder pain.

Superior vena cava syndrome

The superior vena cava (SVC) is a large vein that carries blood from the head and arms down to the heart. It passes next to the upper part of the right lung and the lymph nodes inside the chest. Tumors in this area can press on the superior vena cava, which can cause the blood to back up in the veins. This can lead to swelling in the face, neck, arms, and upper chest (sometimes with a bluish-red skin color). It can also cause headaches, dizziness, and a change in consciousness if it affects the brain. While superior vena cava syndrome can develop gradually over time, in some cases it can become life-threatening, and needs to be treated right away.

Bronchorrhea treatment

Managing the symptoms related to bronchorrhea can be difficult, although there are a few case reports in the literature suggesting the success of various treatments. Macrolide antibiotics and steroids have been shown to reduce sputum volume production in patients with bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma secondary to the anti-inflammatory effect of these drugs, which act as immunomodulators and reduce mucin gene expression 8. Hiratsuka et al. 9 found that clarithromycin treatment in conjunction with inhaled beclomethasone reduced sputum volume from 900 to 300 mL a day in a patient with bronchorrhea secondary to bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma. Furthermore, they found that after stopping the clarithromycin and continuing inhaled beclomethasone alone, the bronchorrhea was controlled for four more months. There also are case reports of successful treatment of bronchorrhea with corticosteroids alone in patients with bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma. Nakajima et al. 10 described the successful treatment of bronchorrhea in a patient with bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma with high-dose pulse methylprednisolone 1000 mg/day followed by oral prednisolone 60 mg/day. The patient’s sputum volume was controlled at 10 mL/day after four weeks of treatment.

There have been case reports about the successful use of inhaled indomethacin for the management of bronchorrhea. Increased transepithelial chloride transport can be promoted by prostaglandins, which are inhibited by indomethacin. Inhaled indomethacin was reported to be effective for severe refractory bronchorrhea in two patients with bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma, not only reducing sputum volume but also improving quality of life 11.

There also have been promising reports of the use of gefitinib in the management of bronchorrhea. Gefitnib is an oral selective EGFR-tyrosine kinase inhibitor. It is thought that EGFR expression and activation causes goblet cell metaplasia from Clara cells and mucus hypersecretion in the airway 12. Takao et al. 13 reported successful treatment of bronchorrhea in a 63-year-old female with bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma after two weeks of gefitinib therapy. She was maintained on gefitinib for nine months without symptoms and without radiologic evidence of recurrence of disease. A recent case report by Popat et al. 6 also showed the successful use of gefitinib in a 46-year-old man with bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma despite his negative EGFR mutation status. The authors suggest that successful use of gefitinib for bronchorrhea is independent of its antiproliferative effect and likely secondary to the role of EGFR in regulating mucin production 6.

There also are case reports of treatment of bronchorrhea with octreotide in patients with bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma. Hudson et al. 14 described the successful use of octreotide through subcutaneous (SC) route to manage the symptoms of bronchorrhea in a 74-year-old female with bronchioloalveolar cell carcinoma. The patient was producing more than 1 L of sputum per day; and after two days of octreotide therapy, sputum production subsided completely.

Octreotide is a synthetic analogue of the hormone somatostatin; and although the exact mechanism of action is unknown, it is thought to act on the same receptors as somatostatin. Octreotide inhibits the secretion of many hormones including gastrin, cholecystokinin, glucagon, growth hormone, insulin, secretin, pancreatic polypeptide, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and vasoactive intestinal peptide. Because of this antisecretoy effect, octreotide reduces gastrointestinal motility, inhibits gall-bladder contraction, reduces secretion of fluids by the intestine and pancreas, and has even been shown to have an analgesic effect 15.

Octreotide has long been used by palliative care practitioners to manage symptoms, including malignant bowel obstruction 16, ascites 17, nausea 18, and gastrointestinal hemorrhage 19. Octreotide also has been used to manage excessive secretions related to fistulae 20. As a result of its antisecretory effect, octreotide is a potent antidiarrheal agent and has been used to manage diarrhea related to carcinoid syndrome20 and human immunodeficiency virus–related diarrhea 21.

Common side effects of octreotide include headache; gastrointestinal reactions including cramps, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and constipation; gallstones; hyperglycemia; hypoglycemia; and transient injection site reactions. Octreotide also is listed among drugs that can prolong the QT interval; however, studies are inconclusive as to whether the prolonged QT interval is the result of octreotide or directly related to the offending illness that required octreotide management, such as acromegaly 22. It is important to note that the patient in our report did not suffer any known side effects related to the octreotide during both the intravenous (IV) and subcutaneous (SC) administration of the drug. She did have pain related to the SC injections; however, no injection site reaction was noted.

It is thought that bronchorrhea is caused by increased transepithelial chloride secretion in the lungs. Octreotide lowers plasma levels of the hormone secretin and there are secretin receptors present on the human lung 13. Secretin is a potent stimulant of electrolyte and water movement, and it has been suggested that inhibiting secretin reduces chloride and water efflux from bronchial epithelial cells, thereby reducing sputum production 14.

As demonstrated in this case report 2, there are many ways to administer octreotide. In addition to the IV and SC routes, there also is an intramuscular depot injection. One intramuscular depot injection may manage symptoms for up to four weeks. However, the intramuscular depot injection can be cost prohibitive. In one large U.S. academic medical center, the cost of a 20 mg depot injection is $2319, versus IV and SC administration, each of which only cost about $10 per day. Given the added cost of administering octreotide daily by the IV or SC routes, further studies are warranted to establish if it is cost-effective to use the intramuscular depot injection in patients who have known improvement of symptoms with octreotide. In addition to the costs, one must take into account the added burden to patients that is associated with daily IV or SC administration.

References- Keal EE. Biochemistry and rheology of sputum in asthma. Postgrad Med J. 1971;47:171–177.

- Pahuja M, Shepherd RW, Lyckholm LJ. The use of octreotide to manage symptoms of bronchorrhea: a case report. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(4):814–818. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.06.008 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4343310

- Read WL, Page NC, Tierney RM, Piccirillo JF, Govindan R. The epidemiology of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma over the past two decades: analysis of the SEER database. Lung Cancer. 2004;45:137–142.

- Takeyama K, Dabbagh K, Lee HM, et al. Epidermal growth factor system regulates mucin production in airways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3081–3086.

- Groneberg DA, Eynott PR, Oates T, et al. Expression of MUC5AC and MUC5B mucins in normal and cystic fibrosis lung. Respir Med. 2002;96:81–86.

- Popat N, Raghavan N, McIvor RA. Severe bronchorrhea in a patient with bronchioloalveolar carcinoma. Chest. 2012;141:513–514.

- Edgerton F, Rao U, Takita H, Vincent RG. Bronchio-alveolar carcinoma. A clinical overview and bibliography. Oncology. 1981;38:269–273.

- Pahuja, M., Shepherd, R. W., & Lyckholm, L. J. (2014). The use of octreotide to manage symptoms of bronchorrhea: a case report. Journal of pain and symptom management, 47(4), 814–818. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.06.008 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4343310

- Hiratsuka T, Mukae H, Ihiboshi H, et al. Severe bronchorrhea accompanying alveolar cell carcinoma: treatment with clarithromycin and inhaled beclomethasone. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai Zasshi. 1998;36:482–487.

- Nakajima T, Terashima T, Nishida J, Onoda M, Koide O. Treatment of bronchorrhea by corticosteroids in a case of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma producing CA19-9. Intern Med. 2002;41:225–228.

- Homma S, Kawabata M, Kishi K, et al. Successful treatment of refractory bronchorrhea by inhaled indomethacin in two patients with bronchioloalveolar carcinoma. Chest. 1999;115:1465–1468.

- Nadel JA. Role of epidermal growth factor receptor activation in regulating mucin synthesis. Respir Res. 2001;2:85–89.

- Takao M, Inoue K, Watanabe F, et al. Successful treatment of persistent bronchorrhea by gefitinib in a case with recurrent bronchioloalveolar carcinoma: a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2003;1:8.

- Hudson E, Lester JF, Attanoos RL, Linnane SJ, Byrne A. Successful treatment of bronchorrhea with octreotide in a patient with adenocarcinoma of the lung. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:200–202.

- Hanks GWC. Oxford textbook of palliative medicine. 4. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2011.

- Mercadante S, Porzio G. Octreotide for malignant bowel obstruction: twenty years after. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2012;83:388–392.

- Cairns W, Malone R. Octreotide as an agent for the relief of malignant ascites in palliative care patients. Palliat Med. 1999;13:429–430.

- Nordesjo-Haglund G, Lonnqvist B, Lindberg G, Hellstrom-Lindberg E. Octreotide for nausea and vomiting after chemotherapy and stem-cell transplantation. Lancet. 1999;353:846. [Letter]

- Kullavanuaya P, Manotaya S, Thong-Ngam D, Mahachai V, Kladchareon N. Efficacy of octreotide in the control of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. J Med Assoc Thai. 2001;84:1714–1720.

- Scott NA, Finnegan S, Irving MH. Octreotide and gastrointestinal fistulae. Digestion. 1990;45(Suppl 1):66–70. discussion 70–71.

- Tinmouth J, Kandel G, Tomlinson G, et al. Systematic review of strategies to measure HIV-related diarrhea. HIV Clin Trials. 2007;8:155–163.

- Fatti LM, Scacchi M, Lavezzi E, et al. Effects of treatment with somatostatin analogues on QT interval duration in acromegalic patients. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2006;65:626–630.