What is vulvar cancer

Vulvar cancer also known as cancer of the vulva, most often affects the two skin folds (or lips) around the vagina, the inner edges of the labia majora or the labia minora. Vulvar cancer starts in the clitoris or in the Bartholin glands less often (see Figure 1 below).

Vulvar cancer usually grows slowly over several years. First, precancerous cells grow on vulvar skin. This is called vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) or dysplasia. Not all vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) cases turn into vulvar cancer, but it is best to treat it early.

Vulvar cancer most often affects women 65 to 75 years of age. However, it can also occur in women 40 years of age or younger. Vulvar cancer may be related to genital warts, a sexually transmitted disease caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV).

In the United States, vulvar cancer accounts for nearly 6% of cancers of the female reproductive organs and 0.7% of all cancers in women. In the United States, women have a 1 in 333 chance of developing vulvar cancer at some point during their life.

The American Cancer Society’s estimates for vulvar cancer in the United States for 2022 are 1, 2:

- New cases: About 6,330 cancers of the vulva will be diagnosed.

- Deaths: About 1,560 women will die of vulvar cancer

- 5-Year Relative Survival: 70.3%. Relative survival is an estimate of the percentage of patients who would be expected to survive the effects of their cancer. It excludes the risk of dying from other causes. Because survival statistics are based on large groups of people, they cannot be used to predict exactly what will happen to an individual patient. No two patients are entirely alike, and treatment and responses to treatment can vary greatly.

- Vulvar cancer deaths as a percentage of All Cancer Deaths: 0.3%.

- Rate of New Cases and Deaths per 100,000: The rate of new cases of vulvar cancer was 2.5 per 100,000 women per year. The death rate was 0.6 per 100,000 women per year. These rates are age-adjusted and based on 2015–2019 cases and 2016–2020 deaths.

- Lifetime Risk of Developing Cancer: Approximately 0.3 percent of women will be diagnosed with vulvar cancer at some point during their lifetime, based on 2017–2019 data.

- In the United States, vulvar cancer accounts for nearly 6% of cancers of the female reproductive organs and 0.7% of all cancers in women. In the United States, women have a 1 in 333 chance of developing vulvar cancer at some point during their life.

Often, vulvar cancer doesn’t cause symptoms at first. Vulvar cancer can make sex painful and difficult.

See your doctor for testing if you notice:

- A lump in the vulva or mass on the vulva

- Vulvar itching or tenderness that lasts more than one month

- Vulvar pain

- A burning pain when passing urine

- Burning in the genital area that lasts even after your doctor has treated the burning

- Bleeding from the vulva (different from your usual menstrual bleeding)

- Changes in the vulvar skin, such as color changes or growths that look like a wart or ulcer

- A mole on the vulva that changes shape or color

- A cut or sore on the vulva that won’t heal

You are at greater risk if you’ve had a human papillomavirus (HPV) infection or have a history of genital warts. Your health care provider diagnoses vulvar cancer with a physical exam and a biopsy. If found early, vulvar cancer has a high cure rate and the treatment options involve less surgery.

Treatment of vulvar cancer varies, depending on your overall health and how advanced the cancer is. It might include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or biologic therapy or a combination of treatments. Biologic therapy boosts your body’s own ability to fight cancer.

The type of surgery depends on the size, depth and spread of the vulvar cancer. Your doctor will review all the options for surgery and the pros and cons of each option. Some people may also need radiation therapy.

When vulvar cancer is found and treated early, the cure rate is over 90%. The key to a cure is to tell your doctor about any warning signs early and to have a biopsy right away. After treatment, be sure to go to all follow-up appointments that your doctor recommends.

The vulva

The vulva is the outer part of the female genitals (Figure 1). The vulva includes the opening of the vagina sometimes called the vestibule. The vulva includes:

- Labia majora: two large, fleshy lips, or folds, of skin.

- Labia minora: small lips just inside the labia majora surrounding the openings to the urethra and vagina.

- Vestibule: space where the vagina opens

- Prepuce: a fold of skin formed by the labia minora that covers the clitoris

- Clitoris: a small protrusion of nerve tissue sensitive to stimulation

- Fourchette: area beneath the vaginal opening where the labia minora meet

- Perineum: area between the vagina and the anus

- Anus: opening at the end of the anal canal

- Urethra: connecting tube to the bladder

Around the opening of the vagina, there are 2 sets of skin folds. The inner set, called the labia minora, are small and hairless. The outer set, the labia majora, are larger, with hair on the outer surface. (Labia is Latin for lips.) The inner and outer labia meet, protecting the vaginal opening and, just above it, the opening of the urethra (the short tube that carries urine from the bladder). The Bartholin glands are found just inside the opening of the vagina — one on each side. These glands produce a mucus-like fluid that acts as a lubricant during sex.

At the front of the vagina, the labia minora meet to form a fold or small hood of skin called the prepuce. The clitoris is beneath the prepuce. The clitoris is an approximately ¾-inch structure of highly sensitive tissue that becomes swollen with blood during sexual stimulation. The labia minora also meet at a place just beneath the vaginal opening, at the fourchette. Beyond the fourchette is the anus, the opening to the rectum. This is where stool comes out of the body. The space between the vagina and the anus is called the perineum.

Figure 1. The vulva – the outer part of the female genitalia

Where does vulval cancer start?

Vulval cancer can start in any part of the female external sex organs. Vulval cancer most often starts in the outer lips (labia majora) or the inner lips (labia minora).

Most vulval cancers do not form quickly. Usually, there is a gradual change in the cells. First, normal cells become abnormal. Then these abnormal cells may go on to develop into cancer.

The medical name for these abnormal cells is vulval epithelial neoplasm or VIN. Your doctor may call these pre cancerous changes.

Vulvar cancer types

Squamous cell carcinomas

Most cancers (90%) of the vulva are squamous cell carcinomas. This type of cancer starts in squamous cells, the main type of skin cells. There are several subtypes of squamous cell carcinoma:

- The keratinizing type is most common. It usually develops in older women and is not linked to infection with human papilloma virus (HPV).

- Basaloid and warty types are less common. These are the kinds more often found in younger women with HPV infections.

- Verrucous carcinoma is an uncommon subtype that’s important to recognize because it’s slow-growing and tends to have a good prognosis (outlook). This cancer looks like a large wart and a biopsy is needed to be sure it’s not a benign (non-cancer) growth.

Adenocarcinoma

Cancer that starts in gland cells is called adenocarcinoma. About 8 of every 100 vulvar cancers are adenocarcinomas. Vulvar adenocarcinomas most often start in cells of the Bartholin glands. These glands are found just inside the opening of the vagina. A Bartholin gland cancer is easily mistaken for a cyst (build-up of fluid in the gland), so it’s common to take awhile to get an accurate diagnosis. Most Bartholin gland cancers are adenocarcinomas. Adenocarcinomas can also form in the sweat glands of the vulvar skin.

Paget disease of the vulva is a condition in which adenocarcinoma cells are found in the top layer of the vulvar skin. Up to 25% of patients with vulvar Paget disease also have an invasive vulvar adenocarcinoma (in a Bartholin gland or sweat gland). In the remaining patients, the cancer cells are found only in the skin’s top layer and have not grown into the tissues below.

Melanoma

Melanomas are cancers that start in the pigment-producing cells that give skin color. They are much more common on sun-exposed areas of the skin, but can start in other areas, such as the vulva. Vulvar melanomas are rare, making up about 6 of every 100 vulvar cancers.

Sarcoma

A sarcoma is a cancer that starts in the cells of bones, muscles, or connective tissue. Less than 2 of every 100 vulvar cancers are sarcomas. Unlike other cancers of the vulva, vulvar sarcomas can occur in females at any age, including in childhood.

Basal cell carcinoma

Basal cell carcinoma, the most common type of skin cancer, is more often found on sun-exposed areas of the skin. Develops from cells called basal cells that are found in the deepest layer of the skin of the vulva. It occurs very rarely on the vulva.

Verrucous carcinoma

Looks like a large wart, again very rare.

Vulvar cancer outlook (prognosis)

The outlook for vulval cancer depends on things such as how far the cancer has spread, your age, and your general health. Generally, the earlier the cancer is detected and the younger you are, the better the chances of treatment being successful.

Overall, around 6 in every 10 women diagnosed with vulval cancer will survive at least five years. However, even after successful treatment, the cancer comes back in up to one in every three cases. You’ll need regular follow-up appointments so your doctor can check if this is happening.

What does vulvar cancer look like

Figure 2. Vulvar cancer – squamous cell carcinoma

Figure 3. Vulvar cancer – basal cell carcinoma

Figure 4. Vulvar cancer – melanoma

Vulvar cancer causes

The cause of vulvar cancer is not known at this time. However, certain risk factors are thought to contribute to development of cancer of the vulva and scientists are beginning to understand how these factors can cause cells in the vulva to become cancerous.

Researchers have made a lot of progress in understanding how certain changes in DNA can cause normal cells to become cancerous. DNA is the chemical that carries the instructions for nearly everything our cells do. We usually look like our parents because they are the source of our DNA. However, DNA affects more than our outward appearance. Some genes (parts of your DNA) contain instructions for controlling when our cells grow and divide.

- Certain genes that promote cell division are called oncogenes.

- Others that slow down cell division or cause cells to die at the right time are called tumor suppressor genes.

Cancers can be caused by DNA mutations (defects) that turn on oncogenes or turn off tumor suppressor genes. Usually DNA mutations related to cancers of the vulva occur during life rather than having been inherited before birth. Acquired mutations may result from cancer-causing chemicals in tobacco smoke. Sometimes they occur for no apparent reason.

Studies suggest that squamous cell cancer of the vulva (the most common type ~ 90%) can develop in at least 2 ways. In up to half of cases, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection appears to have an important role. Vulvar cancers associated with HPV infection (the basaloid and warty subtypes) seem to have certain distinctive features. They are often found along with several other areas of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). The women who have these cancers tend to be younger and are often smokers.

The second process by which vulvar cancers develop does not involve HPV infection. Vulvar cancers not linked to HPV infection (the keratinizing subtype) are usually diagnosed in older women (over age 55). These women may have lichen sclerosis and may also have the differentiated type of VIN. DNA tests from vulvar cancers in older women rarely show HPV infection, but often show mutations of the p53 tumor suppressor gene. The p53 gene is important in preventing cells from becoming cancerous. When this gene has undergone mutation, it is easier for cancer to develop. Younger vulvar cancer patients with HPV infection rarely have p53 mutations.

These discoveries have not yet affected treatment. But they may help in finding ways to prevent cancer of the vulva and at some point might lead to changes in treatment.

Because vulvar melanomas and adenocarcinomas are so rare, much less is known about how they develop.

Risk Factors for Vulvar Cancer

A risk factor is anything that changes a person’s chance of getting a disease such as cancer. Different cancers have different risk factors. For example, exposing skin to strong sunlight is a risk factor for skin cancer. Smoking is a risk factor for many cancers.

There are different kinds of risk factors. Some, such as your age or race, can’t be changed. Others may be related to personal choices such as smoking, drinking, or diet. Some factors influence risk more than others. But risk factors don’t tell us everything. Having a risk factor, or even several, does not mean that a person will get the disease. Also, not having any risk factors doesn’t mean that you won’t get it, either.

Although several risk factors increase the odds of developing vulvar cancer, most women with these risks do not develop it. And some women who don’t have any apparent risk factors develop vulvar cancer. When a woman develops vulvar cancer, it is usually not possible to say with certainty that a particular risk factor was the cause.

Age

The risk of vulvar cancer goes up as women age. Less than 20% of cases are in women younger than age 50, and more than half occur in women over age 70. The average age of women diagnosed with invasive vulvar cancer is 70, whereas women diagnosed with non-invasive vulvar cancer average about 20 years younger.

Human papillomavirus

HPV stands for human papillomavirus. HPVs are a large group of related viruses. They are called papillomaviruses because some of them cause a type of growth called a papilloma. Papillomas — more commonly known as warts — are not cancers. Different HPV types can cause different types of warts in different parts of the body. Some types cause common warts on the hands and feet. Other types tend to cause warts on the lips or tongue.

Certain HPV types can infect the outer female and male genital organs and the anal area, causing raised, bumpy warts. These warts may barely be visible or they may be several inches across. The medical term for genital warts is condyloma acuminatum. Two types of HPV (HPV 6 and HPV 11) cause most cases of genital warts, but are seldom linked to cancer and are known as low-risk HPV.

Other HPV types have been linked with cancers of the cervix, vagina, and vulva in women, cancer of the penis in men, and cancers of the anus and throat (in men and women). These are known as high-risk types of HPV and include HPV 16 and HPV 18 as well as others. Infection with a high-risk HPV may produce no visible signs until pre-cancerous changes or cancer develops.

HPV can pass from one person to another during skin-to-skin contact. One way HPV is spread is through sexual activity, including vaginal and anal intercourse and even oral sex.

Some doctors think there are 2 kinds of vulvar cancer. One kind is associated with HPV infection (more than half of all vulvar cancers are linked to infection with the high-risk HPV types) and tends to occur in younger women. The other is not associated with HPV infection, is more often found in older women, and may develop from a precursor lesion called differentiated vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia.

Vaccines have been developed to help prevent infection with some types of HPV.

Smoking

Smoking exposes people to many cancer-causing chemicals that affect more than their lungs. These harmful substances can be absorbed into the lining of the lungs and spread throughout the body. Smoking increases the risk of developing vulvar cancer. Among women who have a history of HPV infection, smoking further increases the risk of developing vulvar cancer. If women are infected with a high-risk HPV, they have a much higher risk of developing vulvar cancer if they smoke.

HIV infection

HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) causes AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). Because this virus damages the immune system, it makes women more likely to get and to stay infected with HPV. This could increase the risk of vulvar pre-cancer and cancer. Scientists also believe that the immune system plays a role in destroying cancer cells and slowing their growth and spread.

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN)

Squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva usually forms slowly over many years. Pre-cancerous changes often occur first and can last for several years. The medical term most often used for this pre-cancerous condition is vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN). Intraepithelial means that the abnormal cells are only found in the surface layer of the vulvar skin (epithelium).

VIN is typed by how the lesions and cells look: usual-type VIN and differentiated-type VIN. It is sometimes graded VIN 2 and VIN 3, with the number 3 indicating furthest progression toward a true cancer. However, many doctors use only one grade of VIN.

- Usual-type VIN occurs in younger women and is caused by HPV infection. When usual-type VIN changes into invasive squamous cell cancer, it becomes the basaloid or warty subtypes.

- Differentiated-type VIN tends to occur in older women and is not linked to HPV infection. It can progress to the keratinizing subtype of invasive squamous cell cancer.

In the past, the term dysplasia was used instead of VIN, but this term is used much less often now. When talking about dysplasia, there is also a range of increasing progress toward cancer — first, mild dysplasia; next, moderate dysplasia; then severe dysplasia; and, finally, carcinoma in situ.

Although women with VIN have an increased risk of developing invasive vulvar cancer, most cases of VIN never progress to cancer. Still, since it is not possible to tell which cases will become cancers, treatment or close medical follow-up is needed.

The risk of progression to cancer seems to be highest with VIN3 and lower with VIN2. This risk can be altered with treatment. In one study, 88% of untreated VIN3 progressed to cancer, but of the women who were treated, only 4% developed vulvar cancer.

In the past, cases of VIN were included in the broad category of disorders known as vulvar dystrophy. Since this category included a wide variety of other diseases, most of which are not pre-cancerous, most doctors no longer use this term.

Lichen sclerosus

This disorder, also called lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, causes the vulvar skin to become very thin and itchy. The risk of vulvar cancer appears to be slightly increased by lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, with about 4% of women having lichen sclerosus et atrophicus later developing vulvar cancer.

Other genital cancers

Women with cervical cancer also have a higher risk of vulvar cancer. This is probably because these cancers share certain risk factors. The same HPV types that are linked to cervical cancer are also linked to vulvar cancer. Smoking is also linked to a higher risk of both cervical and vulvar cancers.

Melanoma or atypical moles

Women who have had melanoma or dysplastic nevi (atypical moles) in other places have an increased risk of developing a melanoma on the vulva. A family history of melanoma also leads to an increased risk.

Vulvar Cancer Prevention

The risk of vulvar cancer can be lowered by avoiding certain risk factors and by having pre-cancerous conditions treated before an invasive cancer develops. Taking these steps cannot guarantee that all vulvar cancers are prevented, but they can greatly reduce your chances of developing vulvar cancer.

Avoid HPV infection

Infection with human papillomavirus (HPV) is a risk factor for vulvar cancer. In women, HPV infections occur mainly at younger ages and are less common in women over 30. The reason for this is not clear.

HPV is passed from one person to another during skin-to-skin contact with an infected area of the body. HPV can be spread during sexual activity — including vaginal intercourse, anal intercourse, and oral sex — but sex doesn’t have to occur for the infection to spread. All that is needed is skin-to-skin contact with an area of the body infected with HPV. The virus can be spread through genital-to-genital contact. It is even possible to spread a genital infection through hand-to-genital contact.

An HPV infection also seems to be able to be spread from one part of the body to another. This means that an infection may start in the cervix and then spread to the vagina and vulva.

It can be very hard to avoid being exposed to HPV. If you are sexually active, limiting the number of sex partners and avoiding sex with people who have had many other sex partners can help lower your risk of exposure to HPV. But again, HPV is very common, so having sex with even one other person can put you at risk.

Infection with HPV is common, and in most cases your body is able to clear the infection on its own. But in some cases, the infection does not go away and becomes chronic. Chronic infection, especially with high-risk HPV types, can eventually cause certain cancers, including vulvar cancer.

A person can be infected with HPV for years and not have any symptoms, so the absence of visible warts cannot be used to tell if someone has HPV. Even when someone doesn’t have warts (or any other symptom), he (or she) can still be infected with HPV and pass the virus to somebody else.

Condoms

Condoms (rubbers) provide some protection against HPV, but they do not completely prevent infection. Condoms cannot protect completely because they don’t cover every possible HPV-infected area of the body, such as the skin on the genital or anal area. Still, condoms do provide some protection against HPV, and they also protect against HIV and some other sexually transmitted diseases.

Get vaccinated

Vaccines that protect against certain HPV infections are available. All of them protect against infection with HPV subtypes 16 and 18. Some can also protect against infections with other HPV subtypes, including some types that cause anal and genital warts.

These vaccines can only be used to prevent HPV infection –they do not help treat an existing infection. To be most effective, the vaccine should be given before a person becomes exposed to HPV (such as through sexual activity).

All of these vaccines can help prevent cervical cancer and pre-cancers. They are also approved to help prevent anal and genital warts, as well as other cancers.

More HPV vaccines are being developed and tested.

Don’t smoke

Not smoking is another way to lower the risk for vulvar cancer. Women who don’t smoke are also less likely to develop a number of other cancers, like those of the lungs, mouth, throat, bladder, kidneys, and several other organs.

Get regular pelvic checkups

Pre-cancerous vulvar conditions that are not causing any symptoms can be found by regular gynecologic checkups. It is also important to see your health care provider if any problems come up between checkups. Symptoms such as vulvar itching, rashes, moles, or lumps that don’t go away could be caused by vulvar pre-cancer and should be checked out. If vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is found, treating it might help prevent invasive squamous cell vulvar cancer. Also, some vulvar melanomas can be prevented by removing atypical moles.

The vulva is examined at the same time a woman has a pelvic examination. Cervical cancer screening with a Pap test (sometimes combined with a HPV test) is often done at the same time. Neither the Pap test nor the HPV test is used to screen for vulvar cancer. The purpose of these tests is to find cervical cancers and pre-cancers early.

How Pap tests and pelvic examinations are done

First, the skin of the outer lips (labia majora) and inner lips (labia minora) is examined for any visible abnormalities. The health care professional then places a speculum inside the vagina. A speculum is a metal or plastic instrument that keeps the vagina open so that the cervix can be seen clearly. Next, using a small spatula, a sample of cells and mucus is lightly scraped from the exocervix (the surface of the cervix that is closest to the vagina). A small brush or a cotton-tipped swab is then inserted into the cervical opening to take a sample from the endocervix (the inside part of the cervix that is closest to the body of the uterus). Then, the speculum is removed. The doctor then will check the organs of the pelvis by inserting 1 or 2 gloved fingers of one hand into the vagina while he or she palpates (feels) the lower abdomen, just above the pubic bone, with the other. The doctor may do a rectal exam at this time also. It is very important to know that a Pap test is not always done when a pelvic exam is done, so if you are uncertain you should ask if one was done.

Self-exam of the vulva

For most women, the best way to find VIN and vulvar cancer is to report any signs and symptoms to their health care provider and have a yearly well-woman exam. If you have an increased risk of vulvar cancer, you may also want to check your vulva regularly to look for any of the signs of vulvar cancer. This is known as self-examination. Some women choose to examine themselves monthly using a mirror. This can allow you to become aware of any changes in the skin of your vulva. If you do this, look for any areas that are white, darkly pigmented, or red and irritated. You should also note any new growths, nodules, bumps, or ulcers (open sores). Report any of these to a doctor, since they could indicate a vulvar cancer or pre-cancer.

Can Vulvar Cancer Be Found Early?

Having pelvic exams and knowing any signs and symptoms of vulvar cancer greatly improve the chances of early detection and successful treatment. If you have any of the problems discussed in signs and symptoms of vulvar cancers and pre-cancers, you should see a doctor. If the doctor finds anything abnormal during a pelvic examination, you may need more tests to figure out what is wrong. This may mean referral to a gynecologist (specialist in problems of the female genital system).

Knowing what to look for can sometimes help with early detection, but it is even better not to wait until you notice symptoms. Get regular well-women exams.

There is no standard screening for this disease.

Vulvar cancer signs and symptoms

Symptoms depend on whether it is a cancer or pre-cancer and what kind of vulvar cancer it is.

Signs and symptoms of vulvar cancer may include:

- A lump in the vulva or mass on the vulva

- Vulvar itching or tenderness that lasts more than one month

- A burning pain when passing urine

- Vulvar pain

- Burning in the genital area that lasts even after your doctor has treated the burning

- Bleeding from the vulva (different from your usual menstrual bleeding)

- Changes in the vulvar skin, such as color changes or growths that look like a wart or ulcer

- A mole on the vulva that changes shape or color

- A cut or sore on the vulva that won’t heal

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN)

Most women with vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) have no symptoms at all. When a woman with VIN does have a symptom, it is most often itching that does not go away or get better. An area of VIN may look different from normal vulvar skin. It is often thicker and lighter than the normal skin around it. However, an area of VIN can also appear red, pink, or darker than the surrounding skin.

Because these changes are often caused by other conditions that are not pre-cancerous, some women don’t realize that they might have a serious condition. Some try to treat the problem themselves with over-the-counter remedies. Sometimes doctors might not even recognize the condition at first.

Invasive squamous cell cancer of the vulva

Almost all women with invasive vulvar cancers will have symptoms. These can include:

- An area on the vulva that looks different from normal – it could be lighter or darker than the normal skin around it, or look red or pink.

- A bump or lump, which could be red, pink, or white and could have a wart-like or raw surface or feel rough or thick

- Thickening of the skin of the vulva

- Itching

- Pain or burning

- Bleeding or discharge not related to the normal menstrual period

- An open sore (especially if it lasts for a month or more)

Verrucous carcinoma, a subtype of invasive squamous cell vulvar cancer, looks like cauliflower-like growths similar to genital warts.

These symptoms are more often caused by other, non-cancerous conditions. Still, if you have these symptoms, you should have them checked by a doctor or nurse.

Vulvar melanoma

Patients with vulvar melanoma can have many of the same symptoms as other vulvar cancers, such as:

- A lump

- Itching

- Pain

- Bleeding or discharge

Most vulvar melanomas are black or dark brown, but they can be white, pink, red, or other colors. They can be found throughout the vulva, but most are in the area around the clitoris or on the labia majora or minora.

Vulvar melanomas can sometimes start in a mole, so a change in a mole that has been present for years can also indicate melanoma. The ABCDE rule can be used to help tell a normal mole from one that could be melanoma.

- Asymmetry: One-half of the mole does not match the other.

- Border irregularity: The edges of the mole are ragged or notched.

- Color: The color over the mole is not the same. There may be differing shades of tan, brown, or black and sometimes patches of red, blue, or white.

- Diameter: The mole is wider than 6 mm (about 1/4 inch).

- Evolving: The mole is changing in size, shape, or color.

The most important sign of melanoma is a change in size, shape, or color of a mole. Still, not all melanomas fit the ABCDE rule.

If you have a mole that has changed, ask your doctor to check it out.

Bartholin gland cancer

A distinct mass (lump) on either side of the opening to the vagina can be the sign of a Bartholin gland carcinoma. More often, however, a lump in this area is from a Bartholin gland cyst, which is much more common (and is not a cancer).

Paget disease

Soreness and a red, scaly area are symptoms of Paget disease of the vulva.

Vulvar cancer diagnosis

Diagnosing vulvar cancer

Tests and procedures used to diagnose vulvar cancer include:

- Examining your vulva. Your doctor will likely conduct a physical exam of your vulva to look for abnormalities.

- Using a special magnifying device to examine your vulva (colposcopy). During a colposcopy exam, your doctor uses a device that works like a magnifying glass to closely inspect your vulva for abnormal areas.

- Removing a sample of tissue for testing (biopsy). To determine whether an area of suspicious skin on your vulva is cancer, your doctor may recommend removing a sample of skin for testing. During a biopsy procedure, the area is numbed with a local anesthetic and a scalpel or other special cutting tool is used to remove all or part of the suspicious area. Depending on how much skin is removed, you may need stitches.

Biopsy

Certain signs and symptoms might strongly suggest vulvar cancer, but many of them can be caused by changes that aren’t cancer. The only way to be sure cancer is present is for the doctor to do a biopsy. To do this, a small piece of tissue from the changed area is removed and examined under a microscope. A pathologist (a doctor specially trained to diagnose diseases with laboratory tests) will look at the tissue sample with a microscope to see if cancer or pre-cancer cells are present and, if so, what type it is.

The doctor might use a colposcope or a hand-held magnifying lens to select areas to biopsy. A colposcope is an instrument that stays outside the body and has magnifying lenses. It lets the doctor see the surface of the vulva closely and clearly. The vulva is treated with a dilute solution of acetic acid (like vinegar) that causes areas of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) and vulvar cancer to turn white. This makes them easier to see through the colposcope. Examining the vulva with magnification is called vulvoscopy.

Less often, the doctor might wipe the vulva with a dye (called toluidine blue) to find areas of abnormal vulvar skin to biopsy. This dye causes skin with certain diseases — including VIN and vulvar cancer — to turn blue.

Once the abnormal areas are found, a numbing medicine (local anesthetic) is injected into the skin so you won’t feel pain. If the abnormal area is small, it may be completely removed (called an excisional biopsy). Sometimes stitches are needed afterward.

If the abnormal area is larger, a punch biopsy is used to take a small piece of it. The instrument used looks like a tiny apple corer and removes a small, cylinder of skin about 4 mm (about 1/6 inch) across. Stitches aren’t usually needed after a punch biopsy. Depending on the results of the punch biopsy, more surgery may be needed.

Determining the extent of the cancer

Once your diagnosis is confirmed, your doctor works to determine the size and extent (stage) of your cancer. Staging tests can include:

Examination of your pelvic area for cancer spread. Your doctor may do a more thorough examination of your pelvis for signs that the cancer has spread.

Imaging tests. Images of your chest or abdomen may show whether the cancer has spread to those areas. Imaging tests may include X-ray, computerized tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET).

Imaging tests

Imaging tests use sound waves, x-rays, magnetic fields, or radioactive substances to create pictures of the inside of your body.

Chest x-ray

An x-ray of your chest may be done to see if cancer has spread to your lungs.

Computed tomography (CT) scan

A CT scan is an x-ray test that makes detailed cross-sectional images of your body. CT scans are not often needed, but they might be done in women with large vulvar tumors or enlarged lymph nodes. They can also be helpful in deciding whether to do a sentinel lymph node procedure to check groin lymph nodes for cancer spread.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

An MRI uses radio waves and strong magnets instead of x-rays to make images of the body. Like a CT scanner, it produces cross sectional slices of the body. MRI images are very useful in examining pelvic tumors. They can show enlarged lymph nodes in the groin. But, they’re rarely used in patients with early vulvar cancer.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan

A PET scan uses a form of radioactive sugar that’s put into the blood. Body cells take in different amounts of the sugar, depending on how fast they’re growing. Cancer cells grow quickly and are more likely to take up larger amounts of the sugar than normal cells. A special camera is then used to create a picture of areas of radioactivity in the body.

This test can be helpful for spotting collections of cancer cells, and seeing if the cancer has spread to lymph nodes. The picture from a PET scan is not as detailed as a CT or MRI scan, but it provides helpful information about whether abnormal areas seen on these other tests are likely to be cancer or not.

PET scans are also useful when your doctor thinks the cancer has spread, but doesn’t know where (although they aren’t useful for finding cancer spread in the brain). PET scans can be used instead of several different x-rays because they scan your whole body. Often, a machine that combines a PET scanner and a CT scanner (called a PET/CT) is used, which gives more information about areas of cancer and cancer spread.

Other tests to look for cancer

These tests aren’t often used, but if the doctor suspects the cancer has spread to nearby organs, other tests may be used to look for it. These tests let the doctor directly look inside your body for signs of cancer. You may be given drugs to put you into a deep sleep (general anesthesia) while the test is done.

Cystoscopy

The doctor uses a lighted tube to check the inside lining of your bladder. Some advanced cases of vulvar cancer can spread to the bladder, so any suspicious areas noted during this exam are biopsied. This procedure also can be done using a local anesthetic, where the area is just numbed, but some patients may need general anesthesia.

Proctoscopy

This lets the doctor look at the inside of the rectum using a thin, lighted tube. Some advanced cases of vulvar cancer can spread to the rectum. Any suspicious areas are biopsied.

Examination of the pelvis while under anesthesia

Putting the patient into a deep sleep (under anesthesia) allows the doctor to do a more thorough exam that can better evaluate how much the cancer has spread to internal organs of the pelvis.

Blood tests

Your doctor might also order certain blood tests to help get an idea of your overall health and how well certain organs, like your liver and kidneys, are working.

Vulvar cancer staging

After a woman is diagnosed with vulvar cancer, doctors will try to figure out if it has spread, and if so, how far. This process is called staging. The stage of a cancer describes the amount of cancer in the body. It helps determine how serious the cancer is and how best to treat it. Doctors also use a cancer’s stage when talking about survival statistics.

Vulvar cancer stages range from stage I (1) through IV (4). As a rule, the lower the number, the less the cancer has spread. A higher number, such as stage IV, means cancer has spread more. Although each person’s cancer experience is unique, cancers with similar stages tend to have a similar outlook and are often treated in much the same way.

How is the stage determined?

The 2 systems used for staging vulvar cancer, the FIGO (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics) system and the AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer ) TNM staging system are basically the same.

They both stage (classify) this cancer based on 3 pieces of information:

- The extent (size) of the tumor (T): How large and deep has the cancer grown? Has the cancer reached nearby structures or organs like the bladder or rectum?

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): How many lymph nodes has the cancer spread to and has it grown outside of those lymph nodes?

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to distant lymph nodes or distant organs?

Numbers or letters after T, N, and M provide more details about each of these factors. Higher numbers mean the cancer is more advanced. Once a person’s T, N, and M categories have been determined, this information is combined in a process called stage grouping to assign an overall stage.

The staging system in the table below uses the pathologic stage (also called the surgical stage). It is determined by examining tissue removed during an operation. . Sometimes, if surgery is not possible right away, the cancer will be given a clinical stage instead. This stage is based on the results of a physical exam, biopsy, and imaging tests done before surgery.

The system described below is the most recent AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer ) system, effective January 2018.

These systems are not used to stage vulvar melanoma, which is staged like melanoma of the skin.

Vulvar cancer staging can be complex, so ask your doctor to explain it to you in a way you understand.

Your vulvar cancer is assigned a Roman numeral that denotes its stage. Stages of vulvar cancer include:

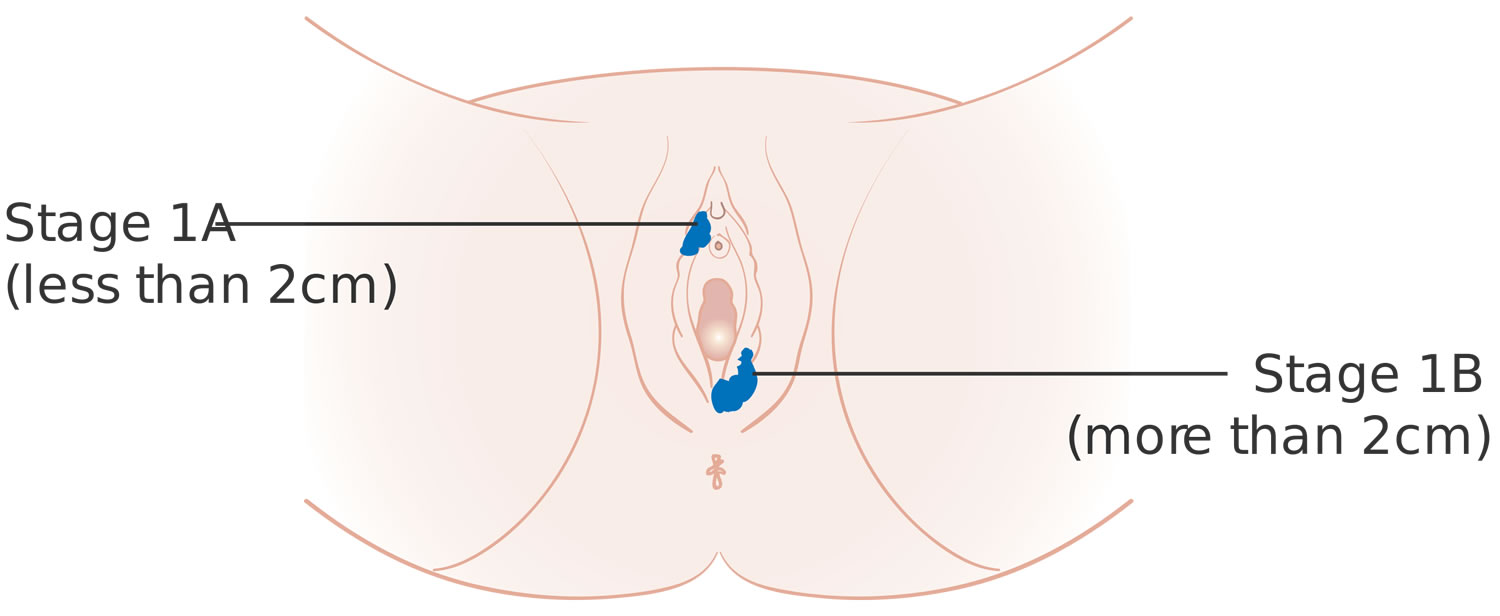

- Stage 1 describes a small tumor that is confined to the vulva or the area of skin between your vaginal opening and anus (perineum). This cancer hasn’t spread to your lymph nodes or other areas of your body.

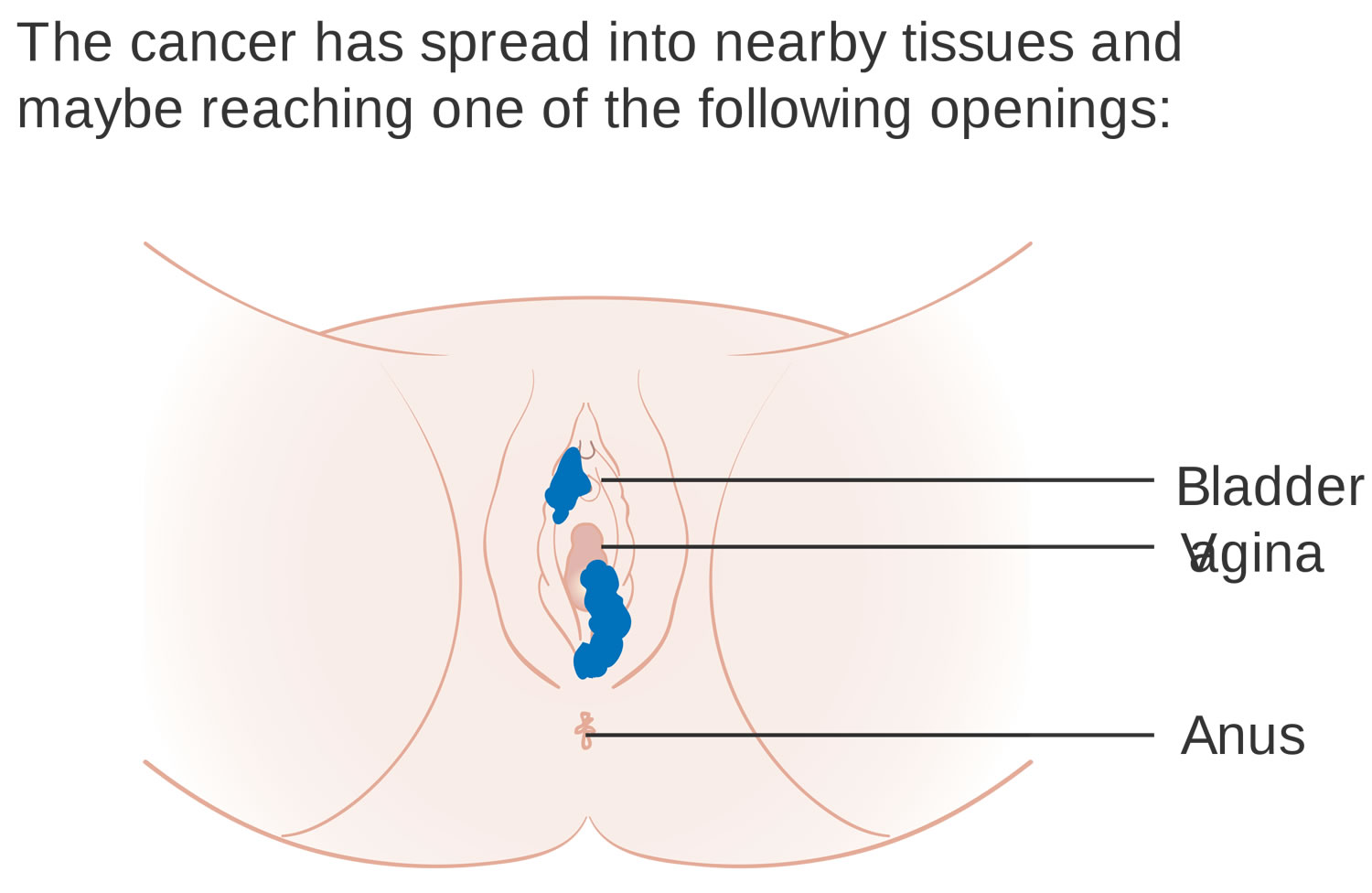

- Stage 2 tumors are those that have grown to include nearby structures, such as the lower portions of the urethra, vagina and anus.

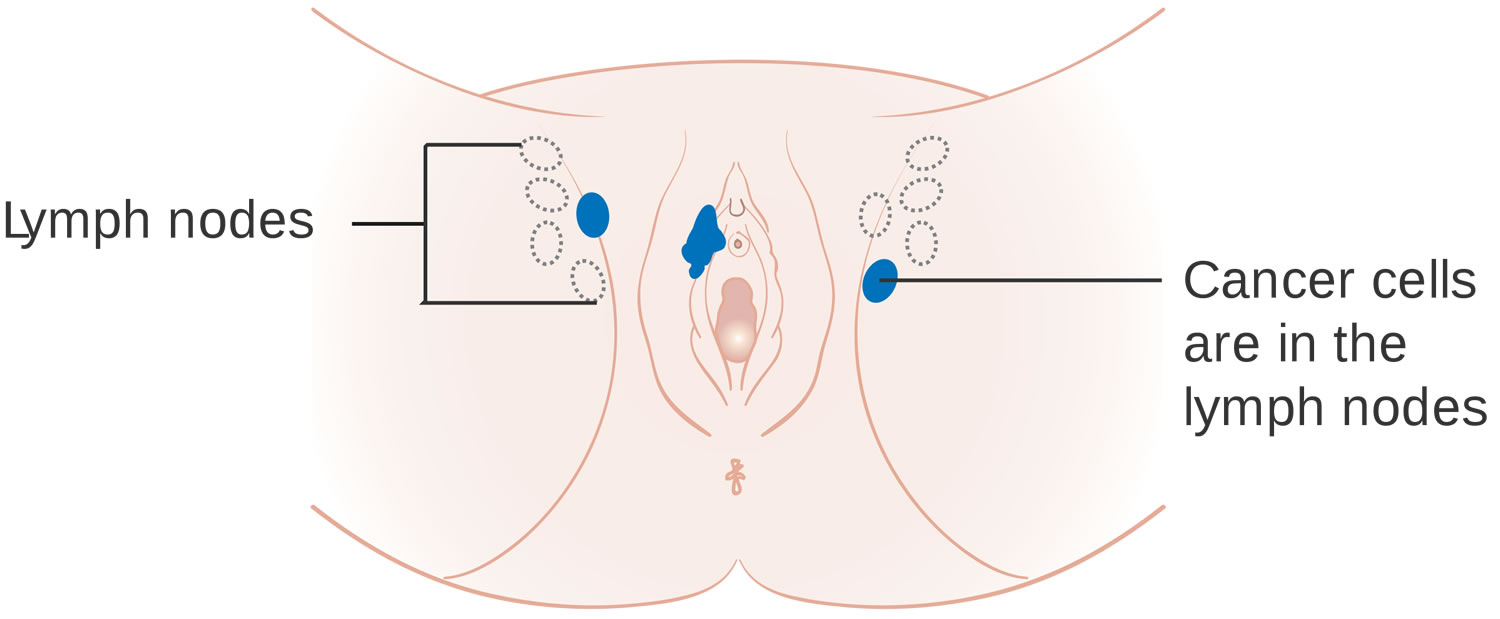

- Stage 3 cancer has spread to lymph nodes.

- Stage 4 signifies a cancer that has spread more extensively to the lymph nodes, or that has spread to the upper portions of the urethra or vagina, or that has spread to the bladder, rectum or pelvic bone. Cancer may have spread (metastasized) to distant parts of your body.

Vulvar melanoma uses a different staging system.

Table 1. Vulvar cancer stages

| AJCC stage | Stage grouping | FIGO stage | Stage description* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1A | T1a N0 M0 | 1A | The cancer is in the vulva or the perineum (the space between the rectum and the vagina) or both and has grown no more than 1 mm into underlying tissue (stroma) and is 2 cm or smaller (about 0.8 inches) (T1a). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 1B | T1b N0 M0 | 1B | The cancer is in the vulva or the perineum or both and is either more than 2 cm (0.8 inches) or it has grown more than 1 mm (0.04 inches) into underlying tissue (stroma) (T1b). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 2 | T2 N0 M0 | 2 | The cancer can be any size and is growing into the anus or the lower third of the vagina or urethra (the tube that drains urine from the bladder) (T2). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

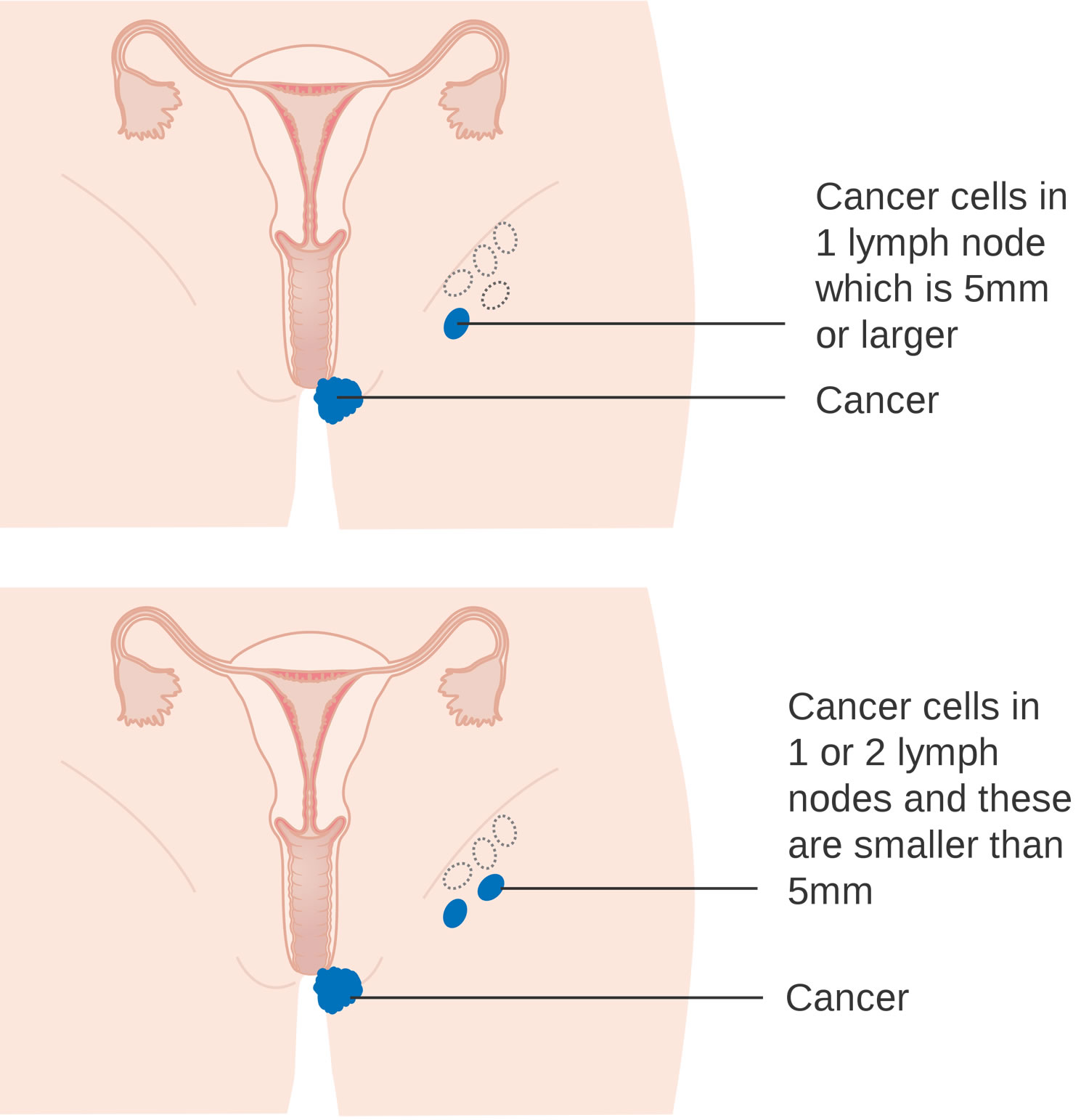

| 3A | T1 or T2 N1 M0 | 3A | Cancer is in the vulva or perineum or both (T1) and may be growing into the anus, lower vagina, or lower urethra (T2). It has either spread to a single nearby lymph node with the area of cancer spread 5 mm or more OR it has spread to 1 or 2 nearby lymph nodes with both areas of cancer spread less than 5 mm (N1). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

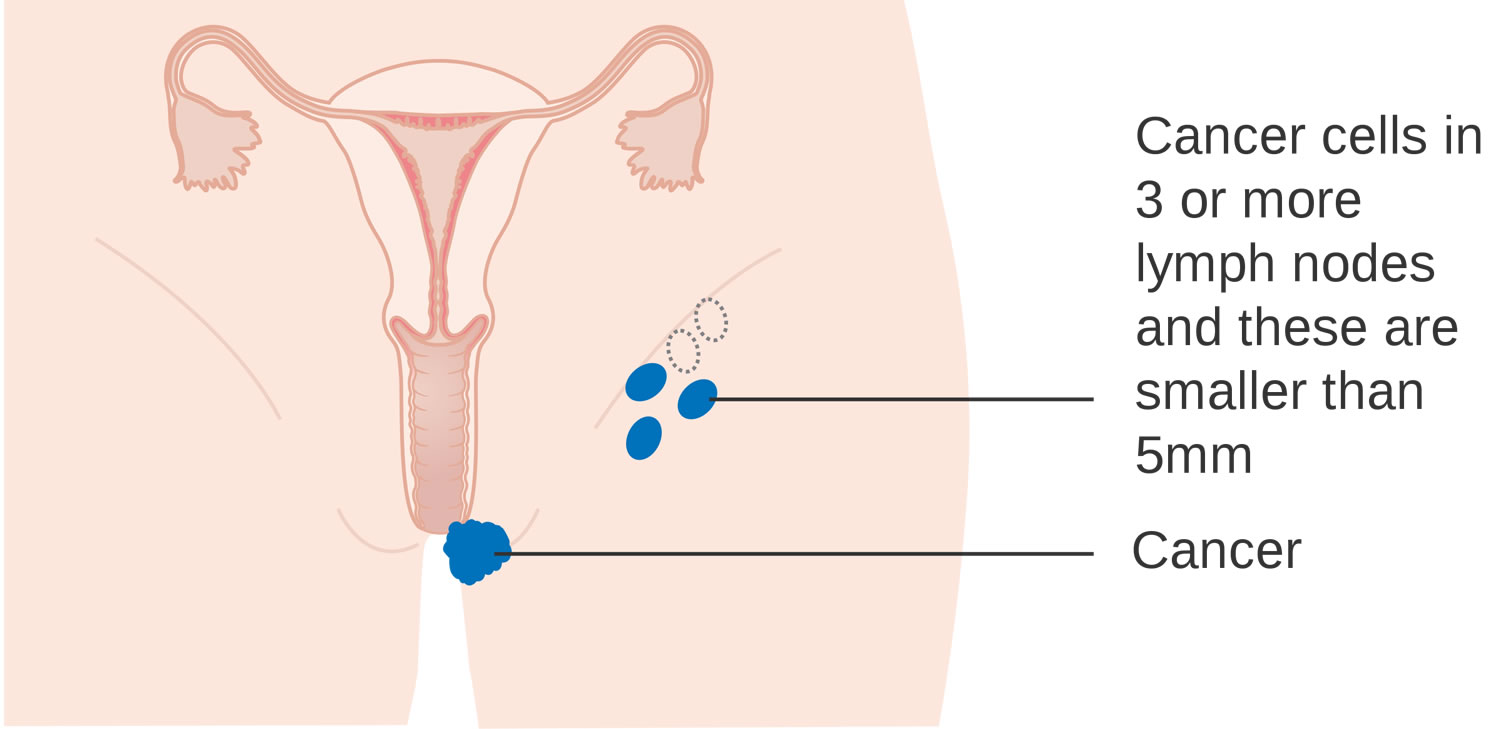

| 3B | T1 or T2 N2a or N2b M0 | 3B | Cancer is in the vulva or perineum or both (T1) and may be growing into the anus, lower vagina, or lower urethra (T2). The cancer has spread either to 3 or more nearby lymph nodes, with all areas of cancer spread less than 5 mm (N2a); OR the cancer has spread to 2 or more lymph nodes with each area of spread 5 mm or greater (N2b). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

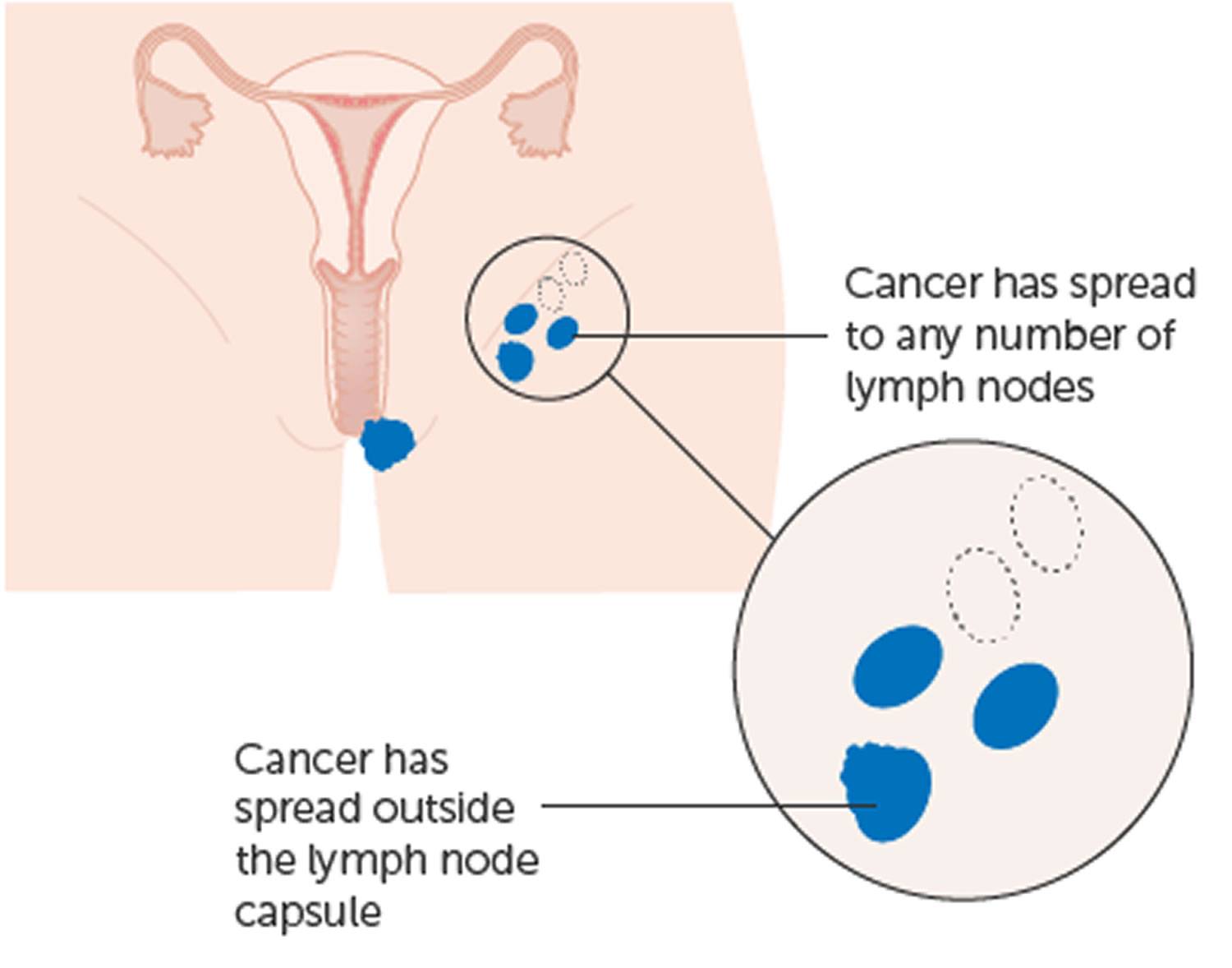

| 3C | T1 or T2 N2c M0 | 3C | Cancer is in the vulva or perineum or both (T1) and may be growing into the anus, lower vagina, or lower urethra (T2). The cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes and has started growing through the outer covering of at least one of the lymph nodes (called extracapsular spread; N2c). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

| 4A | T1 or T2 N3 M0 | 4A | Cancer is in the vulva or perineum or both (T1) and may be growing into the anus, lower vagina, or lower urethra (T2). The cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes and has become stuck (fixed) to the underlying tissue or has caused an ulcer(s) to form on the lymph node(s)(ulceration) (N3). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

| OR | |||

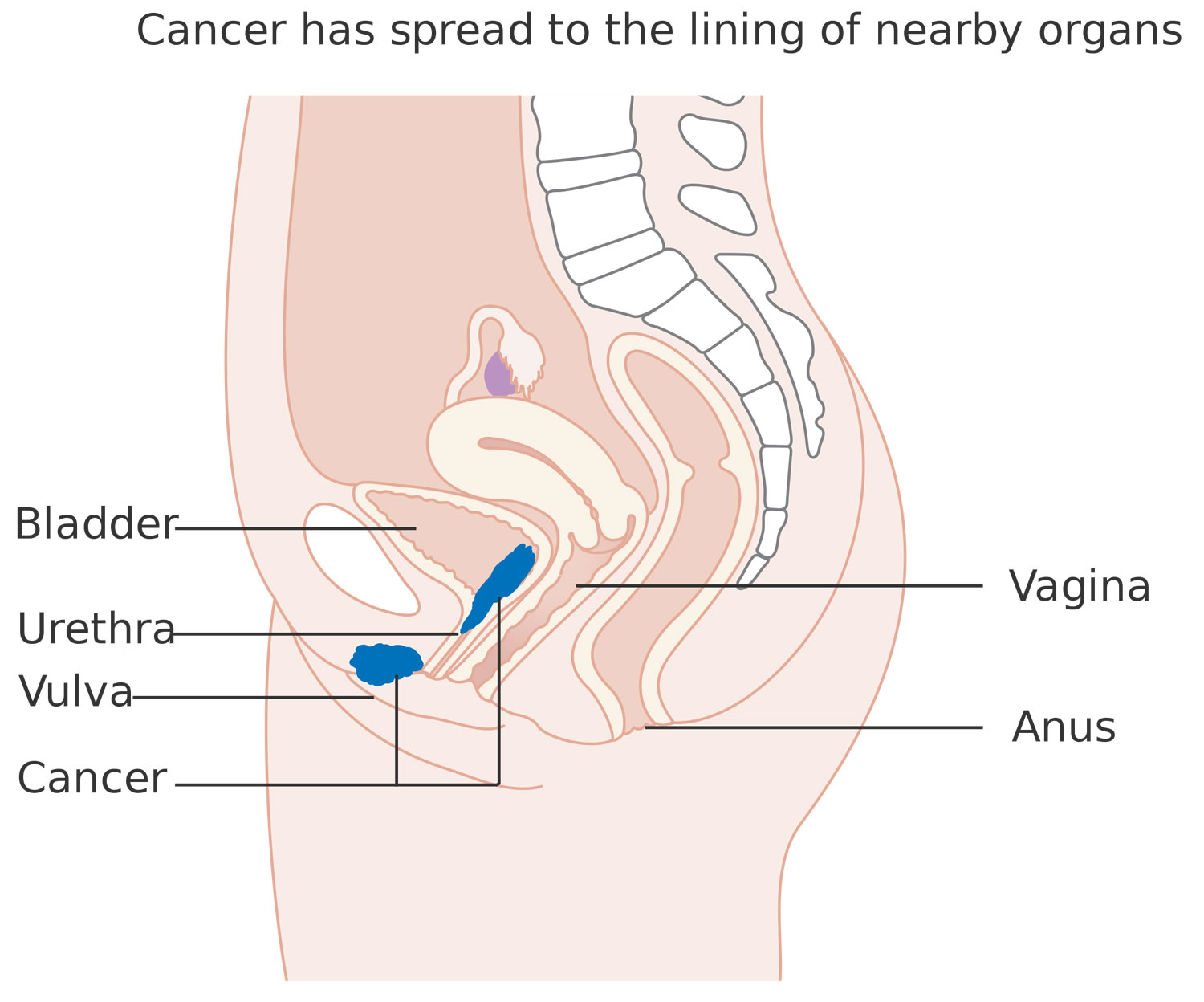

| T3 Any N M0 | 4A | The cancer has spread beyond nearby tissues to the bladder, rectum, pelvic bone, or upper part of the urethra or vagina (T3). It might or might not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (any N). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). | |

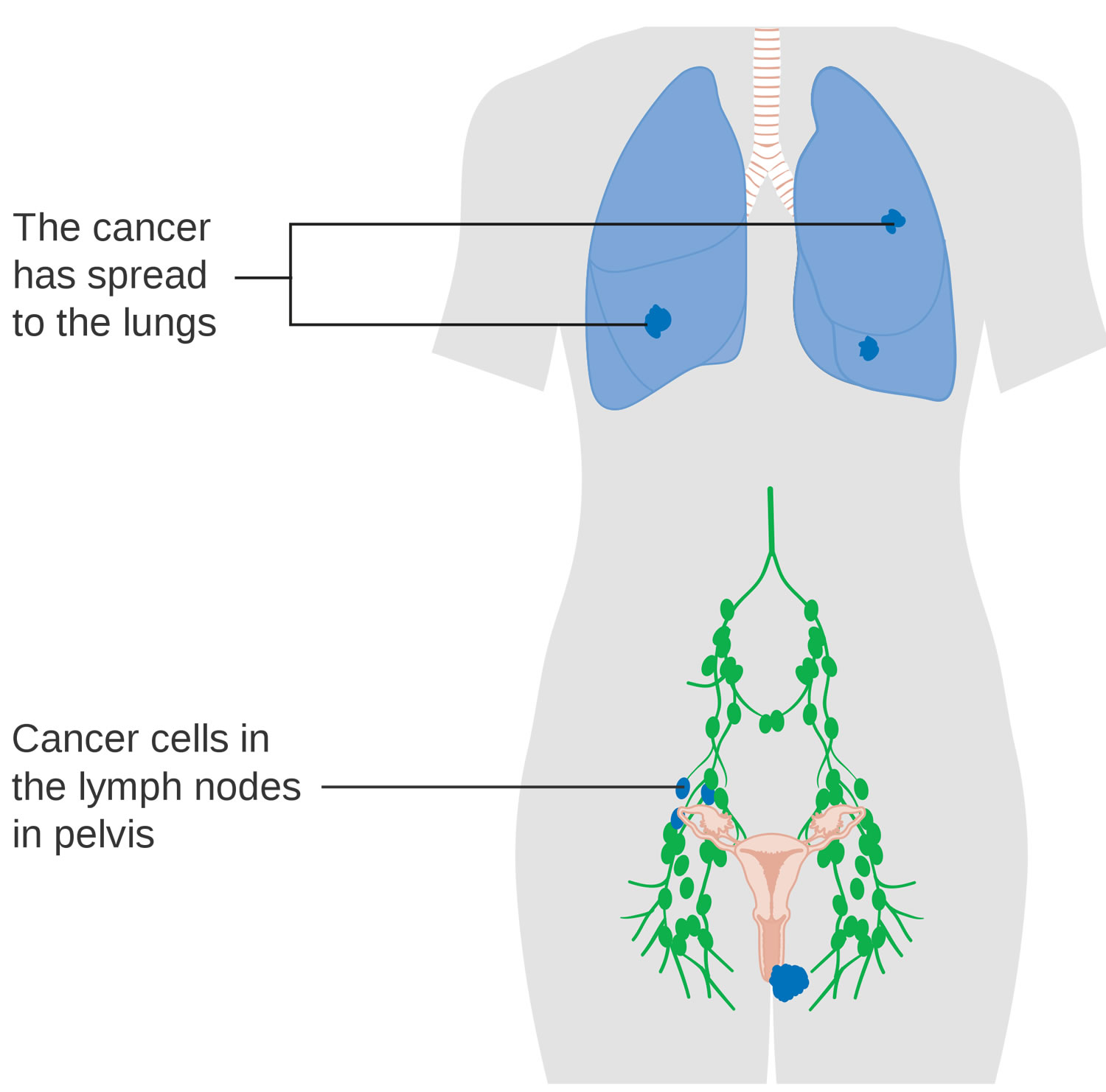

| 4B | Any T Any N M1 | 4B | The cancer has spread to distant lymph nodes (pelvic) or organs such as lung or bone (M1). The cancer can be any size and might or might not have spread to nearby organs (Any T). It might or might not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (Any N). |

Footnotes: * The following additional categories are not listed on the table above:

- TX: Main tumor cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

- T0: No evidence of a primary tumor.

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

Stage 1 vulvar cancer

In stage 1, the cancer is found only in your vulva, or in the vulva and perineum. The perineum is the space between the anus and the vagina. There is no sign cancer in the lymph nodes.

Stage 1 is divided into stages 1A and 1B.

Stage 1A cancer is both of the following:

- the tumor is 2 centimeters or smaller

- has only grown 1 millimeter or less into the skin and tissues underneath the vulva. Cancer has not spread to the lymph nodes.

Stage 1B cancer is:

- the tumor is larger than 2 centimeters OR

- has grown more than 1 millimeter into the skin and tissues underneath the vulva. Cancer has not spread to the lymph nodes.

Stage 1A cancer means you won’t need surgery to check if cancer has spread into your lymph nodes.

For a stage 1B cancer, your specialist will want to check for possible spread to your lymph nodes.

Figure 5. Stage 1 vulvar cancer

Stage 2 vulvar cancer

In stage 2 vulvar cancer, the tumor is any size and has spread to the lower one-third of the urethra, the lower one-third of the vagina, or the lower one-third of the anus. Cancer has not spread to the lymph nodes (there is no sign of cancer in the lymph nodes).

Figure 6. Stage 2 vulvar cancer

Stage 3 vulvar cancer

In stage 3 vulvar cancer, the tumor is any size and has spread to the upper two-thirds of the urethra, the upper two-thirds of the vagina, the inner lining of the bladder or rectum, or to any number of lymph nodes. Stage 3 vulvar cancer is divided into stages 3A, 3B, and 3C.

- In stage 3A, cancer is found in lymph nodes in the groin that are not larger than 5 millimeters.

- In stage 3B, cancer is found in lymph nodes in the groin that are larger than 5 millimeters.

- In stage 3C, cancer is found in lymph nodes in the groin and has extended through the outer covering of the lymph nodes.

Figure 7. Stage 3 vulvar cancer

Figure 8. Stage 3A vulvar cancer

Figure 9. Stage 3B vulvar cancer

Figure 10. Stage 3C vulvar cancer

Stage 4 vulvar cancer

In stage 4 vulvar cancer, the tumor is any size and has become attached to the bone, or cancer has spread to lymph nodes that are not movable or have become ulcerated, or there is distant spread. Stage 4 vulvar cancer is divided into stages 4A and 4B.

- In stage 4A, the cancer is attached to the pelvic bone or has spread to lymph nodes in the groin that are not movable or have become ulcerated.

- In stage 4B, the cancer has spread beyond the pelvis to distant parts of the body.

Figure 11. Stage 4A vulvar cancer

Figure 12. Stage 4B vulvar cancer

Vulvar cancer grade

Grading is a way of dividing cancer cells into groups depending on how much the cells look like normal cells. This gives your doctor an idea of how quickly or slowly the cancer might grow and whether it is likely to spread.

- Grade 1: The cells look very like normal cells. They are also called low grade or well differentiated. They tend to be slow growing and are less likely to spread than higher grade cancer cells.

- Grade 2: The cells look more abnormal and are more likely to spread. This grade is also called moderately differentiated or moderate grade.

- Grade 3: The cells look very abnormal and not like normal cells. They tend to grow quickly and are more likely to spread. They are called poorly differentiated or high grade.

Doctors tend to look at vulvar cancer stage and grade together in order to decide on the best treatment for you.

Vulvar cancer survival rates

The 5-year survival rate refers to the percentage of patients who live at least 5 years after their cancer is diagnosed. Five-year survival rates are used to produce a standard way of discussing prognosis. Of course, many people live much longer than 5 years.

Relative survival rates assume that people will die of other causes and compare the observed survival with that expected for people without vulvar cancer. This is a more accurate way to describe the outlook for patients with a particular type and stage of cancer.

Keep in mind that 5-year survival rates are based on patients diagnosed and initially treated more than 5 years ago. Improvements in treatment often result in a more favorable outlook for women more recently diagnosed with vulvar cancer.

Survival rates are often based on previous outcomes of large numbers of people who had the disease, but they cannot predict what will happen in any particular person’s case. Many other factors may affect a person’s outlook, such as the type of vulvar cancer, the patient’s age and general health, the treatment received, and how well the cancer responds to treatment. Your doctor can tell you how the numbers below may apply to your situation.

These numbers come from the National Cancer Institute’s SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) program. SEER does not list survival rates by FIGO (or AJCC) stage. Instead, it divides vulvar cancers into 3 summary stages 2:

- Localized: The cancer is only in the vulva, without spread to lymph nodes or nearby tissues. This includes stage 1 cancers.

- Regional: The cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes or tissues, but hasn’t spread to distant organs. This includes mainly stage 2, 3 and 4A cancers.

- Distant: The cancer has spread to distant parts of the body such as the lungs, liver or bones. This includes stage 4B cancers.

Table 2. Vulvar cancer survival rates

| SEER Stage | Relative 5-Year Survival Rate |

| Local | 86.2% |

| Regional | 48.4% |

| Distant | 22.9% |

Footnotes:

- Based on women diagnosed with vulvar cancer between 2012 and 2018, All Races, Females by SEER Combined Summary Stage

- Women now being diagnosed with vulvar cancer may have a better outlook than these numbers show. Treatments improve over time, and these numbers are based on people who were diagnosed and treated at least five years earlier.

- These numbers apply only to the stage of the cancer when it is first diagnosed. They do not apply later on if the cancer grows, spreads, or comes back after treatment.

- These numbers don’t take everything into account. Survival rates are grouped based on how far the cancer has spread, but your age, overall health, how well the cancer responds to treatment, and other factors will also affect your outlook.

Vulvar cancer treatment

After the stage of your vulvar cancer is known, your cancer care team will talk with you about treatment options. Think about your options without feeling rushed. If there’s anything you don’t understand, ask to have it explained again.

- The choice of treatment depends largely on the stage of the disease at the time of diagnosis, but other factors can play a part in choosing the best treatment plan, such as your age, your general health, your individual circumstances, and your preferences. Be sure you understand all the risks and side effects of the various options before making a decision.

The treatment that is best for you will depend on:

- the type of vulvar cancer you have

- the stage of your cancer

- the part of your vulva affected

- any previous treatment you might have already had

- your general health

The 3 main types of treatment used for women with vulvar cancer are:

- Surgery. Surgery is the main treatment for vulvar cancer.

- Radiation therapy

- Chemotherapy

Vulvar pre-cancers (vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia or VIN) can also be treated with topical therapy.

Surgery to remove vulvar cancer

Surgery is the main treatment for vulvar cancer. The goal of surgery for vulvar cancer is to remove all the cancer without any loss of the woman’s sexual function. It’s also important to consider how close the tumor is to the urethra and anus, because changes in how waste leaves the body can also have a huge impact on quality of life.

One of the following types of surgery may be done to treat vulvar cancer:

- Wide local excision: A surgical procedure to remove the cancer and some of the normal tissue around the cancer.

- Radical local excision: A surgical procedure to remove the cancer and a large amount of normal tissue around it. Nearby lymph nodes in the groin may also be removed.

- Vulvectomy: A surgical procedure to remove part or all of the vulva:

- Skinning vulvectomy removes only the top layer of skin affected by the cancer. This is an option for treating extensive VIN, but this operation is rarely done.

- In a simple vulvectomy, the entire vulva is removed (the inner and outer labia; sometimes the clitoris, too) as well as tissue just under the skin.

- Modified radical vulvectomy: Surgery to remove most of the vulva. Nearby lymph nodes may also be removed.

- Radical vulvectomy: Surgery to remove the entire vulva. Nearby lymph nodes are also removed.

- Pelvic exenteration: A surgical procedure to remove the lower colon, rectum, and bladder. The cervix, vagina, ovaries, and nearby lymph nodes are also removed. Artificial openings (stoma) are made for urine and stool to flow from the body into a collection bag. This is very complex surgery that can lead to many different kinds of complications.

- If the bladder is removed, a new way to store and pass urine is needed. Usually a short piece of intestine is used to function as a new bladder. This may be connected to the abdominal wall so that urine can be drained when the woman places a catheter into a small opening (called a urostomy). Or urine may drain continuously into a small plastic bag that sticks to the belly over the opening.

- If the rectum and part of the colon are removed, a new way to eliminate solid waste will be needed. This is made by attaching the remaining intestine to the abdominal wall so that stool can pass through a small opening (called a colostomy) into a small plastic bag worn on the front of the abdomen. Sometimes it’s possible to remove a piece of the colon and then reconnect it. In that case, bags or external appliances aren’t needed.

- Lymph node surgery. Because vulvar cancer often spreads to lymph nodes in the groin, these may need to be removed. Treating the lymph nodes is important when it comes to the risk of cancer coming back and long-term outcomes. Still, there’s no one best way to do this. Talk to your doctor about what’s best for you, why it’s best, and what the treatment side effects might be.

- Inguinal lymph node dissection: Surgery to remove lymph nodes in the groin is called an inguinal lymph node dissection. Usually only lymph nodes on the same side as the cancer are removed. If the cancer is in or near the middle, then both sides may have to be done. In the past, the incision (cut in the skin) that was used to remove the cancer in the vulva was made larger to remove the lymph nodes, too. Now, doctors remove the lymph nodes through a separate incision about 1 to 2 cm (less than ½ to 1 inch) below and parallel to the groin crease. The incision is deep, down through membranes that cover the major nerves, veins, and arteries. This exposes most of the inguinal lymph nodes, which are then removed as a solid piece. A major vein, the saphenous vein, may or may not be closed off by the surgeon. Some surgeons will try to save it in an effort to reduce leg swelling (lymphedema) after surgery, but some doctors will not try to save the vein since the problem with swelling is mainly caused by the lymph node removal. After the surgery, a drain is placed into the incision and the wound is closed. The drain stays in until it’s not draining much fluid.

- Sentinel lymph node biopsy: This procedure can help some women avoid having a full inguinal node dissection. It’s used to find and remove the lymph nodes that drain the area where the cancer is. These lymph nodes are known as sentinel lymph nodes because cancer would be expected to spread to them first. The lymph nodes that are removed are then looked at under the microscope to see if they contain cancer cells. If they do, then the rest of the lymph nodes in this area need to be removed. If the sentinel nodes do not contain cancer cells, further lymph node surgery isn’t needed. This procedure can be used instead of an inguinal lymph node dissection for cancers that are fairly small (less than 4 cm) as long as there’s no obvious lymph node spread. To find the sentinel lymph node(s), a small amount of radioactive material and/or blue dye is injected into the tumor site on the day before surgery. The groin is scanned to identify the side (left or right) that picks up the radioactive material. This is the side where the lymph nodes will be removed. During the surgery to remove the cancer, blue dye will be injected again into the tumor site. This allows the surgeon to find the sentinel node by its blue color and then remove it. Sometimes 2 or more lymph nodes turn blue and are removed. If a lymph node near a vulvar cancer is abnormally large, it’s more likely to contain cancer and a sentinel lymph node biopsy is usually not done. Instead, a fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy or surgical biopsy of that lymph node is done to check for cancer cells.

- Vulvar reconstruction. Sometimes these procedures remove a large area of skin from the vulva, requiring skin grafts from other parts of the body to cover the wound. But, most of the time the surgical wounds can be closed without grafts and still provide a very satisfactory appearance. If a skin graft is needed, the gynecologic oncologist may do it. Otherwise, it may be done by a plastic/reconstructive surgeon after the vulvectomy. Reconstructive surgery is available for women who have had more extensive surgery. A reconstructive surgeon can take a piece of skin and underlying fatty tissue and sew it into the area where the cancer was removed. Several sites in the body can be used, but it’s complicated by the fact that the blood supply to the transplanted tissue needs to be kept intact. This is where a skillful surgeon is needed because the tissue must be moved without damaging the blood supply. If you’re having flap reconstruction, ask the surgeon to explain how it will be done, because there’s no set way of doing it.

After the doctor removes all the cancer that can be seen at the time of the surgery, some patients may be given chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy after surgery to kill any cancer cells that are left. Treatment given after the surgery, to lower the risk that the cancer will come back, is called adjuvant therapy.

Complications and side effects of vulvar surgery

Surgery to remove wide areas of vulvar skin carries a risk of complications, such as wound infections and problems with wound healing around the incision or failure of the skin graft to take. The more tissue removed, the greater the risk of these complications. Good hygiene and careful wound care are important.

The urine stream might go to one side because tissue on one or both sides of the urethral opening has been removed.

Other complications of vulvar and groin lymph node surgery include formation of fluid-filled cysts near the surgical wounds, blood clots that may travel to the lungs and urinary infections.

Surgery to your vulva may change sensation in your genital area and reduction of sexual desire or pleasure. Depending on the operation, your genital area may feel numb and you may not be able to achieve orgasm during sexual intercourse.

After vulvar surgery, women often feel discomfort if they wear tight slacks or jeans because the “padding” around the urethral opening and vaginal entrance is gone. The area around the vagina also looks very different.

- Lymphedema: Removal of groin lymph nodes (lymphadenectomy) can result in poor fluid drainage from the legs. This makes fluid build up and leads to leg swelling that is severe and doesn’t go down at night. This is called lymphedema. The risk of lymphedema is higher if radiation is given after surgery. Lymphedema can also cause pain and fatigue. This can also cause problems with sex and a couple will need to use good communication to cope with such problems.

- Sexual impact of vulvectomy: Women often fear their partners will feel turned off by the scarring and loss of the outer genitals, especially during oral sex. Some women may be able to have surgery to rebuild the outer and inner lips of the genitals. It may be difficult for women who have had a vulvectomy to reach orgasm. The outer genitals, especially the clitoris, are important in a woman’s sexual pleasure. For many women, the vagina is just not as sensitive. Women may also notice numbness in their genital area after a radical vulvectomy, but feeling might return over the next few months as nerves slowly heal.

When touching the area around the vagina, and especially the urethra, a light caress and the use of a lubricant can help prevent painful irritation. If scar tissue narrows the entrance to the vagina, penetration may be painful. Vaginal dilators can sometimes help stretch the opening. When scarring is severe, the surgeon can sometimes use skin grafts to widen the entrance. Sometimes, a special type of physical therapy called pelvic floor therapy may help.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-powered energy beams, such as X-rays and protons, to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. Radiation therapy for vulvar cancer is usually administered by a machine that moves around your body and directs radiation to precise points on your skin (external beam radiation). External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward area of the body with cancer.

Radiation therapy is sometimes used to shrink large vulvar cancers in order to make it more likely that surgery will be successful. Radiation is sometimes combined with chemotherapy, which can make cancer cells more vulnerable to radiation therapy.

If cancer cells are discovered in your lymph nodes, your doctor may recommend radiation to the area around your lymph nodes to kill any cancer cells that might remain after surgery. Radiation is sometimes combined with chemotherapy in these situations.

External radiation therapy may also be used as palliative therapy to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life.

Side effects of radiation therapy

Common short-term side effects of radiation therapy to the pelvis include:

- Tiredness can become severe a few weeks after treatment begins. Diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting from radiation can usually be controlled with medicines.

- Skin changes are common in the area the radiation passes through to reach the cancer. This can range from mild, temporary redness to blistering and permanent discoloration.

- Radiation can cause the vulvar area to become sensitive and sore. The skin may release fluid, which can lead to infection, so the area exposed to radiation must be carefully cleaned and protected.

- Radiation can also lead to low blood counts, causing anemia (low red blood cells) and neutropenia (low white blood cells). Low red blood cell counts can lead to feeling tired and short of breath. Low white blood cells can increase the risk of serious infection. The blood counts usually return to normal over time after radiation is stopped.

- Women who receive radiation to the inguinal (groin) area after a lymph node dissection may have problems with the surgical wound site. It may open up or have trouble healing.

- Radiation to the lymph nodes can lead to poor fluid drainage from the legs. The fluid can build up and lead to severe leg swelling that doesn’t go down at night. This is called lymphedema.

These side effects tend to be worse when chemotherapy is given with radiation.If you have side effects from radiation, tell your cancer care team. There are often ways to relieve them.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy also called chemo, is a drug treatment that uses chemicals to kill cancer cells or to stop the growth of cancer cells. Chemotherapy drugs are typically administered through a vein in your arm or by mouth.

When chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein or muscle, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body (systemic chemotherapy). Topical chemotherapy for vulvar cancer may be applied to the skin in a cream or lotion. The way the chemotherapy is given depends on the type and stage of the cancer being treated.

The role of chemo in treating vulvar cancer is not clear. There are no standard chemo treatment plans.

For those with advanced vulvar cancer that has spread to other areas of the body, chemotherapy may be an option. Chemotherapy might be given with radiation therapy before surgery. Chemotherapy helps the radiation work better, and this may shrink the tumor so it’s easier to remove with surgery. Chemotherapy may also be combined with radiation if there’s evidence cancer has spread to the lymph nodes.

At this time, chemo is most often used for vulvar cancers that have spread or have come back after surgery. But so far, the results of using chemo to treat vulvar cancers that have spread to other organs have been disappointing.

Drugs most often used in treating vulvar cancer include cisplatin with or without fluorouracil (5-FU). Another chemo drug, mitomycin, is less commonly used. These are often given at the same time as radiation therapy. (You may hear this called chemoradiation.)

More advanced vulvar cancers may be treated with one or more of these drugs:

- Cisplatin

- Carboplatin

- Vinorelbine

- Paclitaxel

- Erlotinib

Chemotherapy side effects

Many of the chemo drugs used work by attacking cells that are rapidly dividing. This is helpful in killing cancer cells, but these drugs can also affect normal cells, leading to side effects. Side effects of chemo depend on the type of drugs, the amount taken, and the length of time you are treated. Common side effects of some of the drugs used to treat vulvar cancer include:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Loss of hair

- Mouth or vaginal sores

- Changes in the menstrual cycle, premature menopause, and infertility (inability to become pregnant). But most women with vulvar cancer have already gone through menopause.

- Diarrhea

Chemotherapy often affects the blood-forming cells of the bone marrow, leading to low blood counts. This can cause:

- Increased chance of infections (low white blood cell count)

- Increased chance of bleeding and bruising ( low blood platelet count)

- Tiredness (from anemia, which is a low red blood cell count)

Other side effects depend on what drug is used. Most side effects are short-term and stop when the treatment is over, but some chemo drugs can have long-lasting or even permanent effects. For instance, cisplatin can cause nerve damage (called neuropathy). This can lead to numbness, tingling, or even pain in the hands and feet. Cisplatin can also damage the kidneys. To lower the risk of kidney damage, plenty of fluids are given intravenously (IV) before and after each dose.

Ask your cancer care team about the chemo drugs you’ll get and what side effects you can expect. Also be sure to talk with them about any side effects you do have so that they can be treated. For example, you can be given medicine to reduce or prevent nausea and vomiting.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a treatment that uses the patient’s immune system to fight cancer. Substances made by the body or made in a laboratory are used to boost, direct, or restore the body’s natural defenses against cancer. This cancer treatment is a type of biologic therapy.

Imiquimod is an immune response modifier used to treat treat vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN), but it’s not used to treat invasive vulvar cancer and is applied to the skin in a cream.

Vulvar cancer treatment by stage

Treatment for pre cancerous cells (Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia [VIN])

Vulval intraepithelial neoplasm (VIN) is a skin disease in which you have abnormal cells on the surface layer of the vulva. It is not cancer but can sometimes turn into cancer.

The treatment for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) depends on where the disease is, your symptoms, and the risk of your VIN developing into cancer. Your doctor will explain which treatment is best for you. They may include:

- Surgery is the most common treatment for vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) and vulvar cancer. The goal of surgery for vulvar cancer is to remove all the cancer without any loss of the woman’s sexual function. Surgery may be one of the following:

- Separate excision of a lesion: A surgical procedure to remove a lesion of concern.

- Wide local excision: A surgical procedure to remove the area of skin affected by VIN and some of the normal tissue around it.

- Laser surgery: A surgical procedure that uses a laser beam (a narrow beam of intense light) as a knife to make bloodless cuts in tissue or to remove a surface lesion such as a tumor.

- Ultrasound surgical aspiration: A surgical procedure to break the tumor up into small pieces using very fine vibrations. The small pieces of tumor are washed away and removed by suction. This procedure causes less damage to nearby tissue.

- Skinning vulvectomy: The top layer of vulvar skin where the VIN is found is removed. Skin grafts from other parts of the body may be needed to cover the area where the skin was removed.

- Immunotherapy with topical imiquimod.

- A period of no treatment, with close follow up

You will have regular follow up if you have VIN. This helps pick up any early signs of it coming back.

Your specialist will discuss your treatment options if VIN comes back. You may have the same treatment as before, or they may suggest a different type.

Treatment of stage 1 vulvar cancer and stage 2 vulvar cancer

Treatment of stage 1 vulvar cancer and stage 2 vulvar cancer may include the following:

- Surgery (wide local excision).

- Surgery (radical local excision with removal of lymph nodes in the groin and upper thigh).

- Surgery (modified radical vulvectomy or radical vulvectomy with removal of lymph nodes in the groin and upper thigh). Radiation therapy may be given.

- Surgery (radical local excision and removal of sentinel lymph node) followed by radiation therapy in some cases.

- Radiation therapy alone.

Treatment of stage 3 vulvar cancer

Treatment of stage 3 vulvar cancer may include the following:

- Surgery (modified radical vulvectomy or radical vulvectomy with removal of lymph nodes in the groin and upper thigh) with or without radiation therapy.

- Radiation therapy or chemotherapy and radiation therapy followed by surgery.

- Radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy.

Treatment of stage 4A vulvar cancer

Treatment of stage 4A vulvar cancer may include the following:

- Surgery (radical vulvectomy or pelvic exenteration).

- Surgery and radiation therapy.

- Radiation therapy or chemotherapy and radiation therapy followed by surgery.

- Radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy.

Treatment of stage 4B vulvar cancer

There is no standard treatment for stage 4B vulvar cancer. Chemotherapy has been studied and may be used if the patient can tolerate it.

Treatment of recurrent vulvar cancer

Treatment of locally recurrent vulvar cancer may include the following:

- Surgery (wide local excision) with or without radiation therapy.

- Surgery (radical vulvectomy and pelvic exenteration).

- Chemotherapy and radiation therapy with or without surgery.

- Radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy.

- Radiation therapy and surgery.

- Radiation therapy as palliative treatment to relieve symptoms and improve quality of life.

Follow-up tests after treatment

After completing vulvar cancer treatment, your doctor may recommend periodic follow-up exams to look for a cancer recurrence. Even after successful treatment, vulvar cancer can return. Your doctor will determine the schedule of follow-up exams that’s right for you, but doctors generally recommend exams two to four times each year for the first two years after vulvar cancer treatment.

Coping and support

Living with vulvar cancer can be challenging. Although there are no easy answers for coping with vulvar cancer, the following suggestions may help:

- Learn enough about vulvar cancer to feel comfortable making treatment decisions. Ask your doctor to explain the basics of your cancer, such as what types of cells are involved and what stage is your cancer. Also ask your doctor or nurse to recommend good sources of information. Learn enough about your cancer so that you feel comfortable asking questions and discussing your treatment options with your doctor.

- Talk to someone about your feelings. When you feel ready, consider talking to someone you trust about your hopes and fears as you face cancer treatment. This might be a friend, a family member, your doctor, a social worker, a spiritual adviser or a counselor.

- Connect with other cancer survivors. You may find it helpful to talk to other people with vulvar cancer. They can tell you how they’ve coped with problems similar to the ones you’re facing. Ask your doctor about support groups in your area. The National Cancer Institute 5 and the American Cancer Society 6 are good places to start.

- Consider joining a support group for people with cancer. You may find strength and encouragement in being with people who are facing the same challenges you are. Ask your doctor, nurse or social worker about groups in your area. Or try online message boards, such as those available through the American Cancer Society 6.

- Don’t be afraid of intimacy. Your natural reaction to changes in your body may be to avoid intimacy. Although it may not be easy, discuss your feelings with your partner. You may also find it helpful to talk to a therapist, either on your own or together with your partner. Remember that you can express your sexuality in many ways. Touching, holding, hugging and caressing may become far more important to you and your partner.

- Key Statistics for Vulvar Cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/vulvar-cancer/about/key-statistics.html[↩]

- Vulvar Cancer — Cancer Stat Facts. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/vulva.html[↩][↩][↩]

- Vulvar Cancer Stages. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/vulvar-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/staging.html[↩]

- Survival Rates for Vulvar Cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/vulvar-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html[↩]

- National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/[↩]

- American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/[↩][↩]