What is alcohol poisoning

Alcohol (ethanol) poisoning also known as alcohol overdose is generally caused by binge drinking at high intensity or from drinking too many alcoholic beverages, especially in a short period of time. Such drinking can exceed the body’s physiologic capacity to process alcohol, causing the blood alcohol concentration to rise. Alcohol exerts its effects by several mechanisms. Alcohol binds directly to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors in the brain, causing sedation. Alcohol also directly affects cardiac, hepatic, and thyroid tissue. Very high levels of alcohol in the body can shutdown critical areas of the brain that control breathing, heart rate, and body temperature, resulting in death. Alcohol poisoning deaths affect people of all ages but are most common among middle-aged adults and men. The clinical signs and symptoms of an overdose of alcohol occurs when a person has a blood alcohol content sufficient to produce impairments that increase the risk of harm.

- Rapid binge drinking (which often happens on a bet or a dare) is especially dangerous because the victim can drink a fatal dose before losing consciousness.

Alcohol overdoses can range in severity, from minimal impairment with balance, decreased judgment and control, slurred speech, reduced muscle coordination, vomiting, and stupor (reduced level of consciousness and cognitive function) to coma and death 1. However, an individual’s response to alcohol is variable depending on many factors, including the amount and rate of alcohol consumption, health status, consumption of other drugs, age, gender, the amount of food eaten, even ethnicity and metabolic and functional tolerance of the drinker 2, 3.

Alcohol in the form of ethanol (ethyl alcohol) is found in alcoholic beverages, mouthwash, cooking extracts, some medications and certain household products. Other forms of alcohol — including isopropyl alcohol (found in rubbing alcohol, lotions and some cleaning products) and methanol or ethylene glycol (a common ingredient in antifreeze, paints and solvents) — can cause other types of toxic poisoning that require emergency treatment.

A major cause of alcohol poisoning is binge drinking — a pattern of heavy drinking when a male rapidly consumes five or more alcoholic drinks within two hours, or a female downs at least four drinks within two hours. An alcohol binge can occur over hours or last up to several days.

You can consume a fatal dose before you pass out. Even when you’re unconscious or you’ve stopped drinking, alcohol continues to be released from your stomach and intestines into your bloodstream, and the level of alcohol in your body continues to rise.

- If you suspect someone has alcohol poisoning, get medical help immediately. If you or someone you are with has an exposure, call your local emergency number (such as 911) immediately. Cold showers, hot coffee, or walking will not reverse the effects of alcohol overdose and could actually make things worse.

- When in doubt, call for medical help.

- If you are having difficulty in determining whether an individual is acutely intoxicated, contact a health professional immediately – you cannot afford to guess.

- Hundreds of people die each year from acute alcohol intoxication, more commonly known as alcohol poisoning or alcohol overdose. Caused by drinking too much alcohol too fast, it often occurs on college campuses or wherever heavy drinking takes place.

- At the hospital, medical staff will manage any breathing problems, administer fluids to combat dehydration and low blood sugar, and flush the drinker’s stomach to help clear the body of toxins.

- The best way to avoid an alcohol overdose is to drink responsibly if you choose to drink.

Consider joining Alcoholics Anonymous or another mutual support group (see links below). Recovering people who attend support groups regularly do better than those who do not. Groups can vary widely, so shop around for one that’s comfortable. You’ll get more out of it if you become actively involved by having a sponsor and reaching out to other members for assistance.

- Alcoholics Anonymous (https://www.aa.org)

- Moderation Management (https://moderation.org)

- Secular Organizations for Sobriety (https://www.sossobriety.org)

- SMART Recovery (https://www.smartrecovery.org)

- Women for Sobriety (https://womenforsobriety.org)

- Al-Anon Family Groups (https://al-anon.org)

- Adult Children of Alcoholics (https://adultchildren.org)

- National Council on Alcoholism and Drug Dependence (https://recovered.org)

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (https://www.niaaa.nih.gov)

- National Organization on Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (https://fasdunited.org)

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (https://findtreatment.gov)

Figure 1. Alcohol Poisoning Scale

[Source 4]Alcohol is absorbed into the blood mainly from the small bowel, although some is absorbed from the stomach. Alcohol accumulates in blood because absorption is more rapid than oxidation and elimination. The concentration peaks about 30 to 90 min after ingestion if the stomach was previously empty 5.

About 5 to 10% of ingested alcohol is excreted unchanged in urine, sweat, and expired air; the remainder is metabolized mainly by the liver, where alcohol dehydrogenase converts ethanol to acetaldehyde. Acetaldehyde is ultimately oxidized to CO2 and water at a rate of 5 to 10 mL/hour (of absolute alcohol); each milliliter yields about 7 kcal. Alcohol dehydrogenase in the gastric mucosa accounts for some metabolism; much less gastric metabolism occurs in women.

In alcohol-naive people, a blood alcohol level of 300 to 400 mg/dL (BAC 0.3 to 0.4 percent) often causes unconsciousness, and a BAC ≥ 400 mg/dL may be fatal. Sudden death due to respiratory depression or arrhythmias may occur, especially when large quantities are drunk rapidly. This problem is emerging in US colleges but has been known in other countries where it is more common. Other common effects include hypotension and hypoglycemia.

The effect of a particular BAC varies widely; some chronic drinkers seem unaffected and appear to function normally with a BAC in the 300 to 400 mg/dL range, whereas nondrinkers and social drinkers are impaired at a BAC that is inconsequential in chronic drinkers.

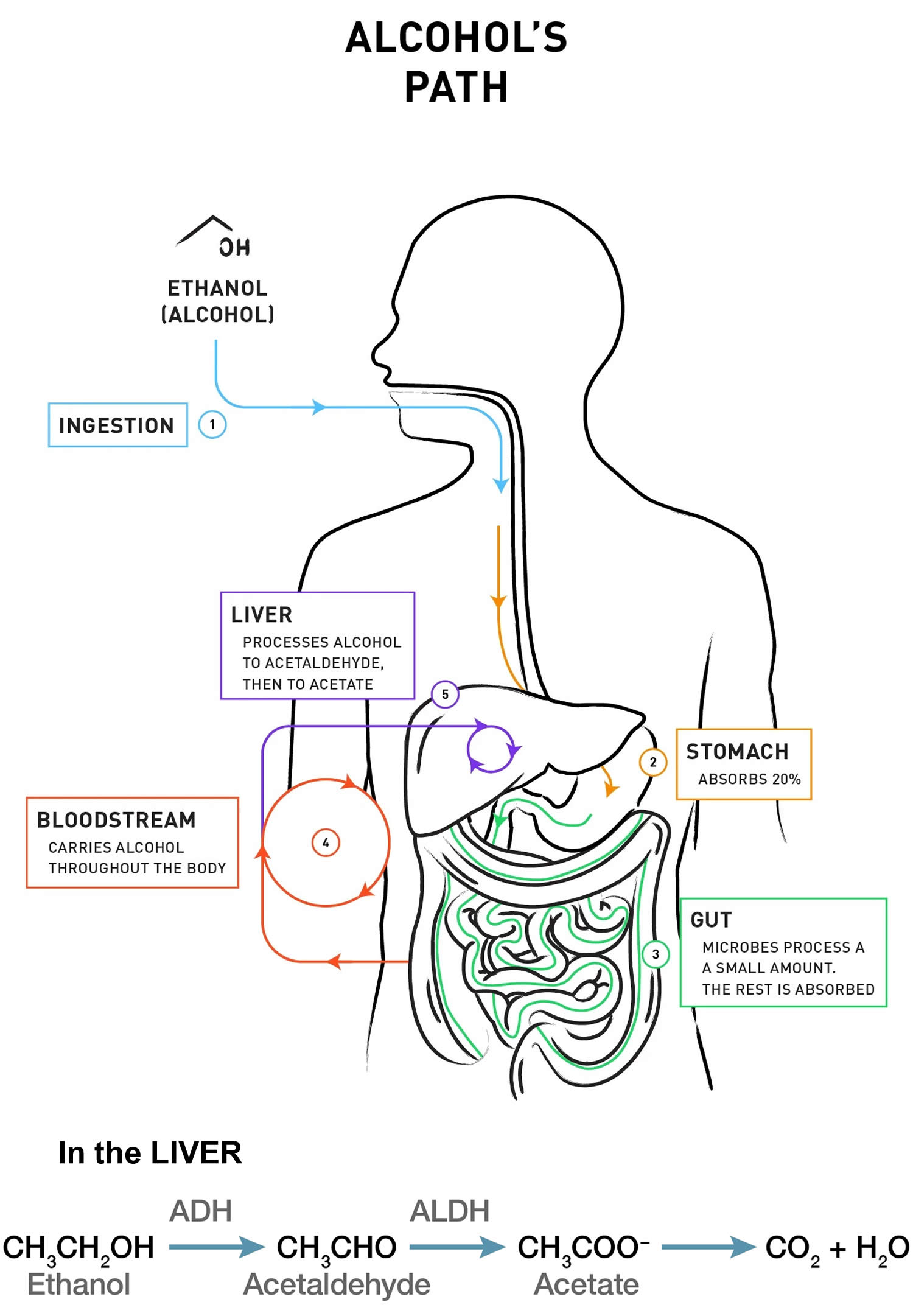

How does my body process alcohol?

When alcohol is consumed, it passes from your stomach and intestines into your bloodstream, where it distributes itself evenly throughout all the water in your body’s tissues and fluids. Drinking alcohol on an empty stomach increases the rate of absorption, resulting in higher blood alcohol level, compared to drinking on a full stomach. In either case, however, alcohol is still absorbed into the bloodstream at a much faster rate than it is metabolized. Thus, your blood alcohol concentration (BAC) builds when you have additional drinks before prior drinks are metabolized.

Your blood alcohol concentration (BAC) is largely determined by how much and how quickly you drink alcohol as well as by your body’s rates of alcohol absorption, distribution, and metabolism. Binge drinking is defined as reaching a BAC of 0.08% (0.08 grams of alcohol per deciliter of blood) or higher. A typical adult reaches this BAC after consuming 4 or more drinks (women) or 5 or more drinks (men), in about 2 hours.

Your body begins to metabolize alcohol within seconds after ingestion and proceeds at a steady rate, regardless of how much alcohol a person drinks or of attempts to sober up with caffeine or by other means. Most of the alcohol is broken down in your liver by the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH). Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) transforms ethanol, the type of alcohol in alcohol beverages, into acetaldehyde, a toxic, carcinogenic compound. Generally, acetaldehyde is quickly broken down to a less toxic compound, acetate, by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) (also called aldehyde dehydrogenase). Acetate then is broken down, mainly in tissues other than the liver, into carbon dioxide (CO2) and water (H2O), which are easily eliminated. To a lesser degree, other enzymes (CYP2E1 and catalase) also break down alcohol to acetaldehyde 6.

Although the rate of metabolism is steady in any given person, it varies widely among individuals depending on factors including liver size and body mass, as well as genetics. There are multiple ADH and ALDH enzymes that are encoded by different genes 6. These genetic variants have been shown to influence a person’s drinking levels and, consequently, the risk of developing alcohol abuse or dependence 7. Studies have shown that people carrying certain ADH and ALDH alleles (one of two or more variants of a gene) are at significantly reduced risk of becoming alcohol dependent. In fact, these associations are the strongest and most widely reproduced associations of any gene with the risk of alcoholism. Some people of Asian descent, for example, carry variations of the genes for alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) or acetaldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) that cause acetaldehyde (a toxic carcinogenic compound) to build up when alcohol is consumed, which in turn produces a flushing reaction and increases the risk of cancer risk 8, 9, 10. 20% of Chinese and Japanese cannot drink alcohol because of an inherited deficiency of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase 11.

Figure 2. How the body processes alcohol

What is binge drinking?

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) defines binge drinking is drinking so much at once that your blood alcohol concentration (BAC) level is 0.08% (0.08 grams of alcohol per deciliter of blood) or more. For a man, this usually happens after having 5 or more drinks within about 2 hours. For a woman, it is after about 4 or more drinks within about 2 hours 12. Not everyone who binge drinks has an alcohol use disorder, but they are at higher risk for getting one.

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), which conducts the annual National Survey on Drug Use and Health, defines binge drinking as 5 or more alcoholic drinks for males or 4 or more alcoholic drinks for females on the same occasion (i.e., at the same time or within a couple of hours of each other) on at least 1 day in the past month.

Binge drinking occurs in the majority of adolescents who drink 13, in half of adults who drink 13 and in 1 in 10 adults over age 65 14 and is increasing among women 15, 16.

Binge drinking causes more than half of the alcohol-related deaths in the U.S. 13. Binge drinking increases the risk of falls, burns, car crashes, memory blackouts, medication interactions, assaults, drownings, and overdose deaths 13.

An average of 6 people die of alcohol poisoning each day in the US from 2010 to 2012 17.

76% of alcohol poisoning deaths are among adults ages 35 to 64 17.

About 76% of those who die from alcohol poisoning are men 17.

Alcohol poisoning deaths

- Most people who die are 35-64 years old.

- Most people who die are men.

- Most alcohol poisoning deaths are among non- Hispanic whites. Although a smaller share of the US population, American Indians/Alaska Natives have the most alcohol poisoning deaths per million people of any of the races.

- Alaska has the most alcohol poisoning deaths per million people, while Alabama has the least.

- Alcohol dependence (alcoholism) was identified as a factor in 30% of alcohol poisoning deaths.

Binge drinking can lead to death from alcohol poisoning.

- Binge drinking (4 or more drinks for women or 5 or more drinks for men in a short period of time) typically leads to a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) that exceeds 0.08 g/dL, the legal limit for driving in all states.

- US adults who binge drink consume an average of about 8 drinks per binge, which can result in even higher levels of alcohol in the body.

- The more you drink the greater your risk of death.

An estimated 88,000 people (approximately 62,000 men and 26,000 women) die from alcohol-related causes annually, making alcohol the fourth leading preventable cause of death in the United States 18. Alcohol deaths accounted for 1 in 10 deaths among working-age adults aged 20–64 years 19. Excessive alcohol use shortened the lives of those who died by about 30 years. These deaths were due to health effects from drinking too much over time, such as breast cancer, liver disease, and heart disease, and health effects from consuming a large amount of alcohol in a short period of time, such as violence, alcohol poisoning, and motor vehicle crashes.

In 2014, alcohol-impaired driving fatalities accounted for 9,967 deaths (31 percent of overall driving fatalities) 20.

Figure 3. Alcohol Poisoning Deaths

[Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 17 ]What counts as a standard drink?

In the United States, a “standard drink” or “alcoholic drink equivalent” is any drink containing 14 grams, or about 0.6 fluid ounces, of “pure” ethanol. One alcoholic drink equals one 12-ounce (oz), or 355 milliliters (mL), can or bottle of beer (with 5% alcohol by volume or alc/vol), a 5-ounce (148 mL) glass of wine (with 12% alc/vol), 1 wine cooler, 1 cocktail, 1 shot of hard liquor; or 1.5 ounces of 80-proof distilled spirits (such as whiskey, rum, or tequila) (with 40% alc/vol) 21. While there is no guaranteed safe amount of alcohol for anyone, the answer from current research is, the less alcohol, the better 22, 23. Alcohol is a carcinogen associated with cancer of the oral cavity, pharynx, larynx, esophagus, colon, rectum, liver, and female breast, with breast cancer risk rising with less than one drink a day. Your whole body is impacted by alcohol use not just your liver, but also your brain, gut, pancreas, lungs, cardiovascular system, immune system, and more and may explain, for example, challenges in managing hypertension, atrial fibrillation, diabetes, and recurrent lung infections.

The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism defines one standard drink as any one of these:

- 12 ounces (355 milliliters) of regular beer (about 5 percent alcohol)

- 8 to 9 ounces (237 to 266 milliliters) of malt liquor (about 7 percent alcohol)

- 5 ounces (148 milliliters) of unfortified wine (about 12 percent alcohol)

- 1.5 ounces (44 milliliters) of 80-proof hard liquor (about 40 percent alcohol)

Mixed drinks may contain more than one serving of alcohol and take even longer to metabolize.

If you want to know the alcohol content of a canned or bottled beverage, start by checking the label. Not all beverages are required to list the alcohol content, so you may need to search online for a reliable source of information, such as the bottler’s Web site. For fact sheets about how to read wine, malt beverage, and distilled spirits labels, visit the consumer corner of the U.S. Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau 24.

Although the “standard” drink amounts are helpful for following health guidelines, they may not reflect customary serving sizes. In addition, while the alcohol concentrations listed are “typical,” there is considerable variability in alcohol content within each type of beverage (e.g., beer, wine, distilled spirits). If you want to know how much alcohol is in a cocktail or a beverage container, try the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rethinking Drinking – Alcohol calculators (https://www.rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/Tools/Calculators/Default.aspx).

The 2020-2025 U.S. Dietary Guidelines states that for adults who choose to drink alcohol, women should have 1 drink or less in a day and men should have 2 drinks or less in a day 25. These amounts are not intended as an average but rather a daily limit.

You are abusing alcohol when:

- You drink 7 drinks per week or more than 3 drinks per occasion (for women).

- You drink more than 14 drinks per week or more than 4 drinks per occasion (for men).

- You have more than 7 drinks per week or more than 3 drinks per occasion (for men and women older than 65).

- Consuming these amounts of alcohol harms your health, relationships, work, and/or causes legal problems.

Footnotes: The sample standard drinks above are just starting points for comparison, because actual alcohol content and customary serving sizes can vary greatly both across and within types of beverages. For example:

- Beer: The most popular type of beer is light beer, which may be light in calories, but not necessarily in alcohol. The mean alc/vol for light beers is 4.3%, almost as much as a regular beer with 5% alc/vol.4 On average, craft beers have more than 5% alc/vol and flavored malt beverages, such as hard seltzers, more than 6% alc/vol.4 Some craft beers and flavored malt beverages have in the range of 8-9% alc/vol. Advise patients to check container labels for the alcohol content and adjust their intake accordingly.

- Wine: The largest category of wine is table wine. On average, table wines contain about 12% alc/vol4 and can range from about 5% to 16%. Larger wine glasses can encourage larger pours. People are often unaware that a 25-ounce (750ml) bottle of table wine with 12% alc/vol contains five standard drinks, and one with 14% alc/vol holds nearly six.

- Cocktails: Recipes for cocktails often exceed one standard drink’s worth of alcohol. The cocktail content calculator on Rethinking Drinking shows the alcohol content in sample cocktails.

Do you have a drinking problem?

While there is no guaranteed safe amount of alcohol for anyone, the answer from current research is, the less alcohol, the better 22, 23. The 2020-2025 U.S. Dietary Guidelines states that for adults who choose to drink alcohol, women should have 1 drink or less in a day and men should have 2 drinks or less in a day 25. These amounts are not intended as an average but rather a daily limit. Many people with alcohol problems cannot tell when their drinking is out of control. It is important to be aware of how much you are drinking. You should also know how your alcohol use may affect your life and those around you.

Many patients may think that heavy drinking is not a concern because they can “hold their liquor.” However, having an innate “low level of response” or “high tolerance” to alcohol is a reason for caution, as people with this trait tend to drink more and thus have an increased risk for alcohol-related problems including alcohol use disorder 26. People who drink within the U.S. Dietary Guidelines, too, may be unaware that even if they don’t feel a “buzz,” driving can be impaired 27.

Doctors consider your drinking medically unsafe when you drink:

- Many times a month, or even many times a week

- 3 to 4 drinks (or more) in 1 day

- 5 or more drinks on one occasion monthly, or even weekly

Twelve questions to ask if you think you may have a drinking problem

- Have you ever decided to stop drinking for a week or so, but only lasted for a couple of days? (Yes or No)

- Do you wish people would mind their own business about your drinking– stop telling you what to do? (Yes or No)

- Have you ever switched from one kind of drink to another in the hope that this would keep you from getting drunk? (Yes or No)

- Have you had to have a drink upon awakening during the past year? (Yes or No)

- Do you envy people who can drink without getting into trouble? (Yes or No)

- Have you had problems connected with drinking during the past year? (Yes or No)

- Has your drinking caused trouble at home? (Yes or No)

- Do you ever try to get “extra” drinks at a party because you do not get enough? (Yes or No)

- Do you tell yourself you can stop drinking any time you want to, even though you keep getting drunk when you don’t mean to? (Yes or No)

- Have you missed days of work or school because of drinking? (Yes or No)

- Do you have “blackouts”? (Yes or No) (Alcohol-related blackouts are gaps in a person’s memory for events that occurred while they were intoxicated. These gaps happen when a person drinks enough alcohol to temporarily block the transfer of memories from short-term to long-term storage, known as memory consolidation, in a brain area called the hippocampus.)

- Have you ever felt that your life would be better if you did not drink? (Yes or No)

If you answer YES 4 or more times – you are probably in trouble with alcohol.

However severe your drinking problem may seem, most people with alcohol use disorder can benefit from treatment. Unfortunately, less than 10 percent of them receive any treatment.

Ultimately, receiving treatment can improve your chances of success in overcoming alcohol use disorder.

Talk with your doctor to determine the best course of action for you.

Levels of alcohol use

There are four levels of alcohol use:

- Social drinking: There is no guaranteed safe amount of alcohol for anyone. According to the “Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2020-2025” 25, adults of legal drinking age can choose not to drink or to drink in moderation by limiting intake to 2 drinks or less in a day for men (less than 14 drinks per week for men) and 1 drink or less in a day for women (less than 7 drinks per week for women), when alcohol is consumed. Drinking less is better for health than drinking more.

- At risk consumption: the level of drinking begins to pose a health risk. Frequent heavy drinking raises the risk for both acute harms, such as falls and medication interactions, and for chronic consequences, such as alcohol use disorder and dose-dependent increases in liver disease, heart disease and cancers 28, 29, 30.

- For men, consuming more than 5 drinks on any day or more than 15 drinks per week

- For women, consuming more than 4 drinks on any day or more than 8 drinks per week

- Binge drinking on 5 or more days in the past month

- Heavy drinking thresholds for women are lower than men because after consumption, alcohol distributes itself evenly in body water, and pound for pound, women have proportionally less water in their bodies than men do. This means that after a woman and a man of the same weight drink the same amount of alcohol, the woman’s blood alcohol concentration (BAC) will tend to be higher, putting her at greater risk for harm.

- Problem drinking: drinking causes serious problems to you, your family, your work and society in general

- Alcohol dependence and addiction:

- periodic or chronic intoxication

- uncontrollable craving for drink when sober

- tolerance to the effects of alcohol

- psychological and/or physical dependence

How much alcohol is too much?

Unlike food, which can take hours to digest, alcohol is absorbed quickly by your body — long before most other nutrients. And it takes a lot more time for your body to get rid of the alcohol you’ve consumed. Most alcohol is processed (metabolized) by your liver.

The more you drink, especially in a short period of time, the greater your risk of alcohol poisoning.

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans defines moderate drinking as up to 1 drink per day for women and up to 2 drinks per day for men 31. In addition, the Dietary Guidelines do not recommend that individuals who do not drink alcohol start drinking for any reason.

You are drinking too much if:

- On any day in the past year, For MEN: you drink more than 4 “standard” drinks per day and For WOMEN: you drink more than 3 “standard” drinks per day.

- On average, you drink alcohol more than 2 days per week.

- On a typical drinking day, you drink more than 4 standard drinks (for Men) or more than 3 standard drinks (for Women).

Figure 4. U.S. Adults Drinking Patterns

[Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rethinking Drinking 32]You have had more “heavy drinking days” in the past year than 7 in 10 U.S. adults . Although your weekly average is typically within low-risk limits, once or twice a week you have more than the single-day limit of 4 drinks for men. You may be surprised that the majority of U.S. adults never exceed the low-risk drinking limits.

Your particular risk depends on how much, how quickly, and how often you drink. According to the National Institutes of Health survey, about 1 in 3 people in your drinking pattern group has an alcohol use disorder. In addition, just a single episode of drinking too much, too quickly, can lead to a serious injury.

Excessive drinking includes binge drinking, heavy drinking, and any drinking by pregnant women or people younger than age 21.

- Binge drinking, the most common form of excessive drinking, is defined as consuming

+ For women, 4 or more drinks within 2 hours.

+ For men, 5 or more drinks within 2 hours. - Heavy drinking is defined as consuming

+For women, the consumption of more than 3 drinks on any day or more than 7 per week.

+ For men, it is more than 4 drinks on any day or more than 14 per week.

This pattern of drinking too much, too often, is associated with an increased risk for alcohol use disorders. This dangerous pattern of drinking typically results in a blood alcohol level of .08% for the average adult and increases the risk of immediate adverse consequences.

Most people who drink excessively are not alcoholics or alcohol dependent 33

You can reduce your risks. Research shows that people who stay within both the single-day and weekly limits have the lowest rates of alcohol-related problems. It’s safest to quit, however, if you already have signs of a problem.

Figure 5. “Low-Risk” Drinking Patterns

[Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rethinking Drinking 34]“Low risk” is not “no risk.” Even within these limits, alcohol can cause problems if people drink too quickly, have health problems, or are older (both men and women over 65 are generally advised to have no more than 3 drinks on any day and 7 per week) 34. Based on your health and how alcohol affects you, you may need to drink less or not at all.

Research demonstrates “low-risk” drinking levels for men are no more than 4 drinks on any single day AND no more than 14 drinks per week 35. For women, “low-risk” drinking levels are no more than three drinks on any single day AND no more than seven drinks per week 35. To stay low-risk, you must keep within both the single-day and weekly limits.

Even within these limits, you can have problems if you drink too quickly, have health conditions, or are over age 65. Older adults should have no more than three drinks on any day and no more than seven drinks per week.

Research shows that women start to have alcohol-related problems at lower drinking levels than men do 32. One reason is that, on average, women weigh less than men. In addition, alcohol disperses in body water, and pound for pound, women have less water in their bodies than men do. So after a man and woman of the same weight drink the same amount of alcohol, the woman’s blood alcohol concentration will tend to be higher, putting her at greater risk for harm.

Risk factors for alcohol poisoning

A number of factors can increase your risk of alcohol poisoning, including:

- Your size and weight

- Your overall health

- Whether you’ve eaten recently

- Whether you’re combining alcohol with other drugs

- The percentage of alcohol in your drinks

- The rate and amount of alcohol consumption

- Your tolerance level.

Signs and symptoms of alcohol poisoning

Alcohol poisoning signs and symptoms include 36:

- Confusion, slurred speech.

- Unsteady walking.

- Internal (stomach and intestinal) bleeding.

- Vomiting, sometimes bloody.

- Seizures.

- Slowed breathing (less than eight breaths a minute).

- Irregular breathing (a gap of more than 10 seconds between breaths).

- Blue-tinged skin or pale skin (clammy skin).

- Extremely low body temperature (hypothermia).

- Stupor (decreased level of alertness), even coma.

- Dulled responses, such as no gag reflex (which prevents choking).

- Passing out (unconsciousness) and can’t be awakened

- Abdominal pain.

- Chronic alcohol overuse can lead to additional symptoms and multiple organ failure.

- When in doubt, call for medical help.

- If you are having difficulty in determining whether an individual is acutely intoxicated, contact a health professional immediately – you cannot afford to guess.

- Hundreds of people die each year from acute alcohol intoxication, more commonly known as alcohol poisoning or alcohol overdose. Caused by drinking too much alcohol too fast, it often occurs on college campuses or wherever heavy drinking takes place.

Severe complications can result from alcohol poisoning, include:

- Choking. Alcohol may cause vomiting. Because it depresses your gag reflex, this increases the risk of choking on vomit if you’ve passed out.

- Stopping breathing. Accidentally inhaling vomit into your lungs can lead to a dangerous or fatal interruption of breathing (asphyxiation).

- Severe dehydration. Vomiting can result in severe dehydration, leading to dangerously low blood pressure and fast heart rate.

- Seizures. Your blood sugar level may drop low enough to cause seizures.

- Hypothermia. Your body temperature may drop so low that it leads to cardiac arrest.

- Irregular heartbeat. Alcohol poisoning can cause the heart to beat irregularly or even stop.

- Brain damage. Heavy drinking may cause irreversible brain damage.

- Death. Any of the issues above can lead to death.

Your blood alcohol level can continue to rise even when you are unconscious. Alcohol in the stomach and intestine continues to enter the bloodstream and circulate throughout the body.

- It is dangerous to assume that an unconscious person will be fine by sleeping it off. Alcohol acts as a depressant, hindering signals in the brain that control automatic responses such as the gag reflex 4. Alcohol also can irritate the stomach, causing vomiting. With no gag reflex, a person who drinks to the point of passing out is in danger of choking on vomit, which, in turn, could lead to death by asphyxiation. Even if the drinker survives, an alcohol overdose can lead to long-lasting brain damage.

Alcohol poisoning treatment

- When in doubt, call for medical help.

- If you are having difficulty in determining whether an individual is acutely intoxicated, contact a health professional immediately – you cannot afford to guess.

- Hundreds of people die each year from acute alcohol intoxication, more commonly known as alcohol poisoning or alcohol overdose. Caused by drinking too much alcohol too fast, it often occurs on college campuses or wherever heavy drinking takes place.

While waiting for the emergency transport, gently turn the intoxicated person on his/her side in case they throw up (vomit) and maintain that position by placing a pillow in the small of the person’s back. This is important to prevent aspiration (choking) should the person vomit. Stay with the person until medical help arrives.

DO NOT make the person throw up unless told to do so by a health care professional or Poison Control.

Check the person frequently to make sure their condition does not get worse.

A more difficult situation occurs when an intoxicated person appears to be “sleeping it off.” It is important to understand that even though a person may be semi-conscious, alcohol already in the stomach will continue to enter the bloodstream and circulate throughout the body. The person’s life still may be in danger.

If you should encounter such a situation, place the person on his/her side, help them maintain that position, and watch them closely for signs of alcohol poisoning. If any signs appear, call your local emergency number. If you can wake an adult who has drunk too much alcohol, move the person to a comfortable place to sleep off the effects. Make sure the person will not fall or get hurt.

If the person is not alert (unconscious) or only somewhat alert (semi-conscious), emergency assistance may be needed.

What to Expect at the Emergency Room

The health care provider will measure and monitor the person’s vital signs, including temperature, pulse, breathing rate, and blood pressure. The person may receive:

- Airway support, including oxygen, breathing tube through the mouth (intubation) and ventilator (breathing machine).

- Blood and urine tests

- Chest x-ray

- CT (computerized tomography, or advanced imaging) scan

- EKG (electrocardiogram, or heart tracing)

- Fluids through the vein (intravenous or IV), sometime with thiamin, Magnesium and vitamins

- Medicines to treat symptoms

How long does alcohol poisoning last?

Survival over 24 hours past the drinking binge usually means the person will recover. A withdrawal syndrome may develop as alcohol levels in the blood drop, so the person should be observed and kept safe for at least another 24 hours.

Alcohol Withdrawal

For detail treatment and management including, signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal please read more here: What are signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal.

References- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital Signs: Alcohol Poisoning Deaths — United States, 2010–2012. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6353a2.htm

- Caplan YH, Goldberger BA, eds. Garriott’s medicolegal aspects of alcohol, sixth edition. Tucson, AZ: Lawyers and Judges Publication Company; 2015.

- National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol overdose: the dangers of drinking too much. Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2013. https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/AlcoholOverdoseFactsheet/Overdosefact.htm

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol Overdose: The Dangers of Drinking Too Much. https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/AlcoholOverdoseFactsheet/Overdosefact.htm

- Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. Alcohol Toxicity and Withdrawal. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/special-subjects/recreational-drugs-and-intoxicants/alcohol-toxicity-and-withdrawal

- Edenberg HJ. The genetics of alcohol metabolism: role of alcohol dehydrogenase and aldehyde dehydrogenase variants. Alcohol Res Health. 2007;30(1):5-13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3860432

- Hurley TD, Edenberg HJ, Li T-K. Pharmacogenomics: The Search for Individualized Therapies. Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH; 2002. The pharmacogenomics of alcoholism; pp. 417–441.

- Zaso MJ, Goodhines PA, Wall TL, Park A. Meta-Analysis on Associations of Alcohol Metabolism Genes With Alcohol Use Disorder in East Asians. Alcohol Alcohol. 2019 May 1;54(3):216-224. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agz011

- Goldman D, Oroszi G, Ducci F. The genetics of addictions: uncovering the genes. Nat Rev Genet. 2005 Jul;6(7):521-32. doi: 10.1038/nrg1635

- Hurley TD, Edenberg HJ. Genes encoding enzymes involved in ethanol metabolism. Alcohol Res. 2012;34(3):339-44. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3756590

- National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Alcohol-Use Disorders: Diagnosis, Assessment and Management of Harmful Drinking and Alcohol Dependence. Leicester (UK): British Psychological Society (UK); 2011. (NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 115.) Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK65487

- Drinking Levels Defined. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/alcohol-health/overview-alcohol-consumption/moderate-binge-drinking

- White AM, Tapert S, Shukla SD. Binge Drinking. Alcohol Res. 2018;39(1):1-3. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6104965

- Han BH, Moore AA, Ferris R, Palamar JJ. Binge Drinking Among Older Adults in the United States, 2015 to 2017. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019 Oct;67(10):2139-2144. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16071

- Keyes KM, Jager J, Mal-Sarkar T, Patrick ME, Rutherford C, Hasin D. Is There a Recent Epidemic of Women’s Drinking? A Critical Review of National Studies. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2019 Jul;43(7):1344-1359. doi: 10.1111/acer.14082. Epub 2019 Jun 5. Erratum in: Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2020 Feb;44(2):579.

- Wilsnack RW, Wilsnack SC, Gmel G, Kantor LW. Gender Differences in Binge Drinking. Alcohol Res. 2018;39(1):57-76. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6104960

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol Poisoning Deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/alcohol-poisoning-deaths/index.html

- Mokdad, A.H.; Marks, J.S.; Stroup, D.F.; and Gerberding, J.L. Actual causes of death in the United States 2000. [Published erratum in: JAMA 293(3):293–294, 298] JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association 291(10):1238–1245, 2004. http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/198357

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol Deaths. https://www.cdc.gov/features/alcohol-deaths/index.html

- National Center for Statistics and Analysis. 2014 Crash Data Key Findings (Traffic Safety Facts Crash Stats. Report No. DOT HS 812 219). Washington, DC: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, 2015. https://crashstats.nhtsa.dot.gov/Api/Public/ViewPublication/812219

- The Basics: Defining How Much Alcohol is Too Much. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/health-professionals-communities/core-resource-on-alcohol/basics-defining-how-much-alcohol-too-much#pub-toc1

- GBD 2016 Alcohol and Drug Use Collaborators. The global burden of disease attributable to alcohol and drug use in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018 Dec;5(12):987-1012. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30337-7. Epub 2018 Nov 1. Erratum in: Lancet Psychiatry. 2019 Jan;6(1):e2.

- GBD 2016 Alcohol Collaborators. Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2018 Sep 22;392(10152):1015-1035. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2. Epub 2018 Aug 23. Erratum in: Lancet. 2018 Sep 29;392(10153):1116. Erratum in: Lancet. 2019 Jun 22;393(10190):e44.

- U.S. Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau. Alcohol Beverage Labeling and Advertising. https://www.ttb.gov/consumer/labeling_advertising.shtml

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th Edition. December 2020. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2021-03/Dietary_Guidelines_for_Americans-2020-2025.pdf

- Schuckit MA. A Critical Review of Methods and Results in the Search for Genetic Contributors to Alcohol Sensitivity. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2018 May;42(5):822-835. doi: 10.1111/acer.13628

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Preventing impaired driving. Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23(1):31-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6761696

- Dawson DA, Li TK, Grant BF. A prospective study of risk drinking: at risk for what? Drug Alcohol Depend. 2008 May 1;95(1-2):62-72. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.12.007

- Roerecke M, Rehm J. Chronic heavy drinking and ischaemic heart disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Heart. 2014 Aug 6;1(1):e000135. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2014-000135

- Scoccianti C, Straif K, Romieu I. Recent evidence on alcohol and cancer epidemiology. Future Oncol. 2013 Sep;9(9):1315-22. https://doi.org/10.2217/fon.13.94

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. 2015 – 2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 8th Edition, Washington, DC; 2015. https://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rethinking Drinking – What’s your pattern ? https://www.rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/How-much-is-too-much/Is-your-drinking-pattern-risky/Whats-Your-Pattern.aspx?type=MaleFrequentlyOverSingleDayONLY&avg=10&day=5&week=2

- Esser MB, Hedden SL, Kanny D, Brewer RD, Gfroerer JC, Naimi TS. Prevalence of Alcohol Dependence Among US Adult Drinkers, 2009–2011. Prev Chronic Dis 2014;11:140329. https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2014/14_0329.htm

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rethinking Drinking – What’s low-risk drinking ? https://www.rethinkingdrinking.niaaa.nih.gov/How-much-is-too-much/Is-your-drinking-pattern-risky/Whats-Low-Risk-Drinking.aspx

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Beyond Hangovers. https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Hangovers/beyondHangovers.htm

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Ethanol poisoning. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002644.htm