Barrett’s esophagus

Barrett’s esophagus is a condition in which tissue that is similar to the lining of your intestine replaces the tissue lining your esophagus. Doctors call this process intestinal metaplasia. People with Barrett’s esophagus are more likely to develop a rare type of esophageal cancer called esophageal adenocarcinoma 1. The esophagus is also called the food pipe or swallowing tube.

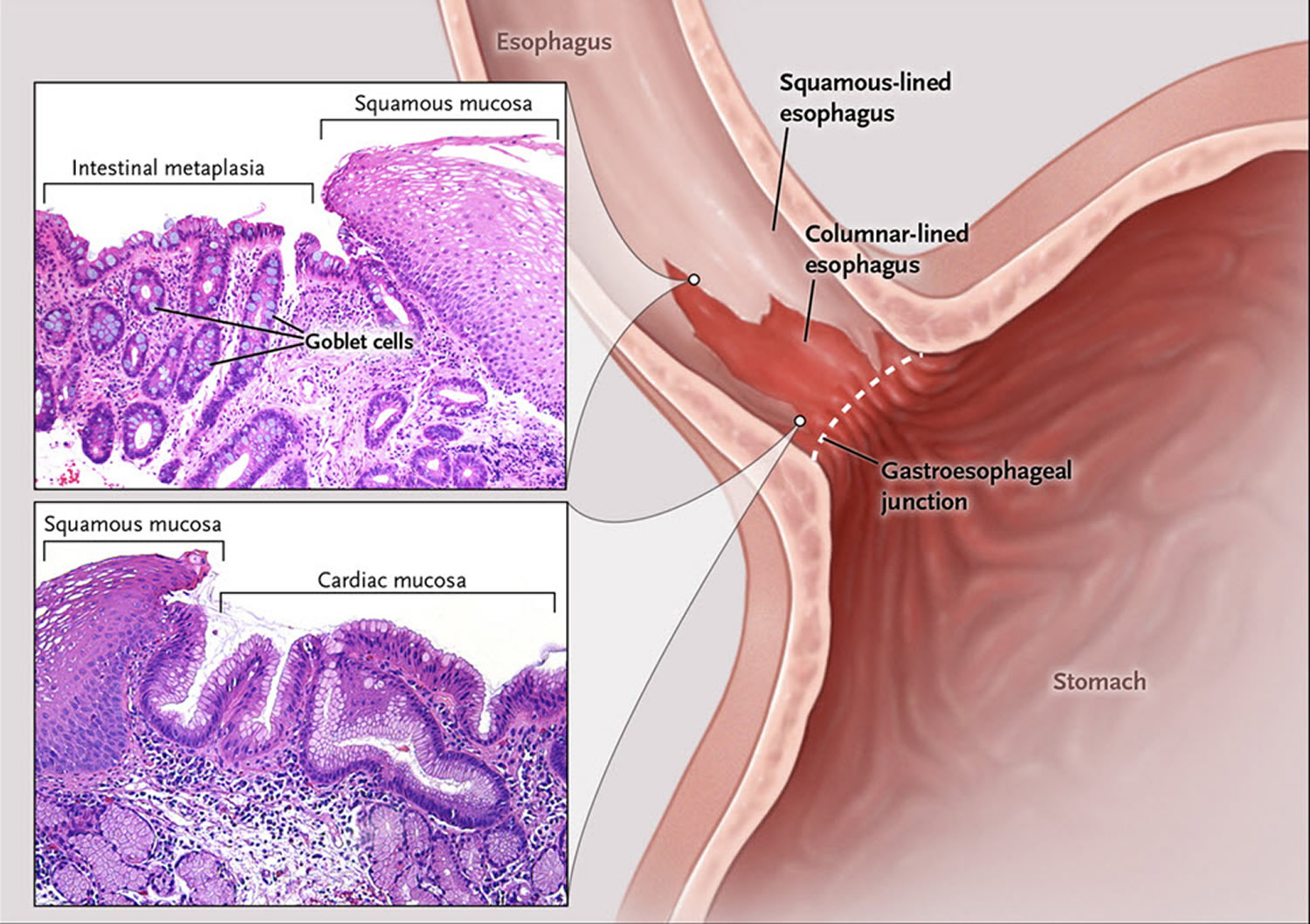

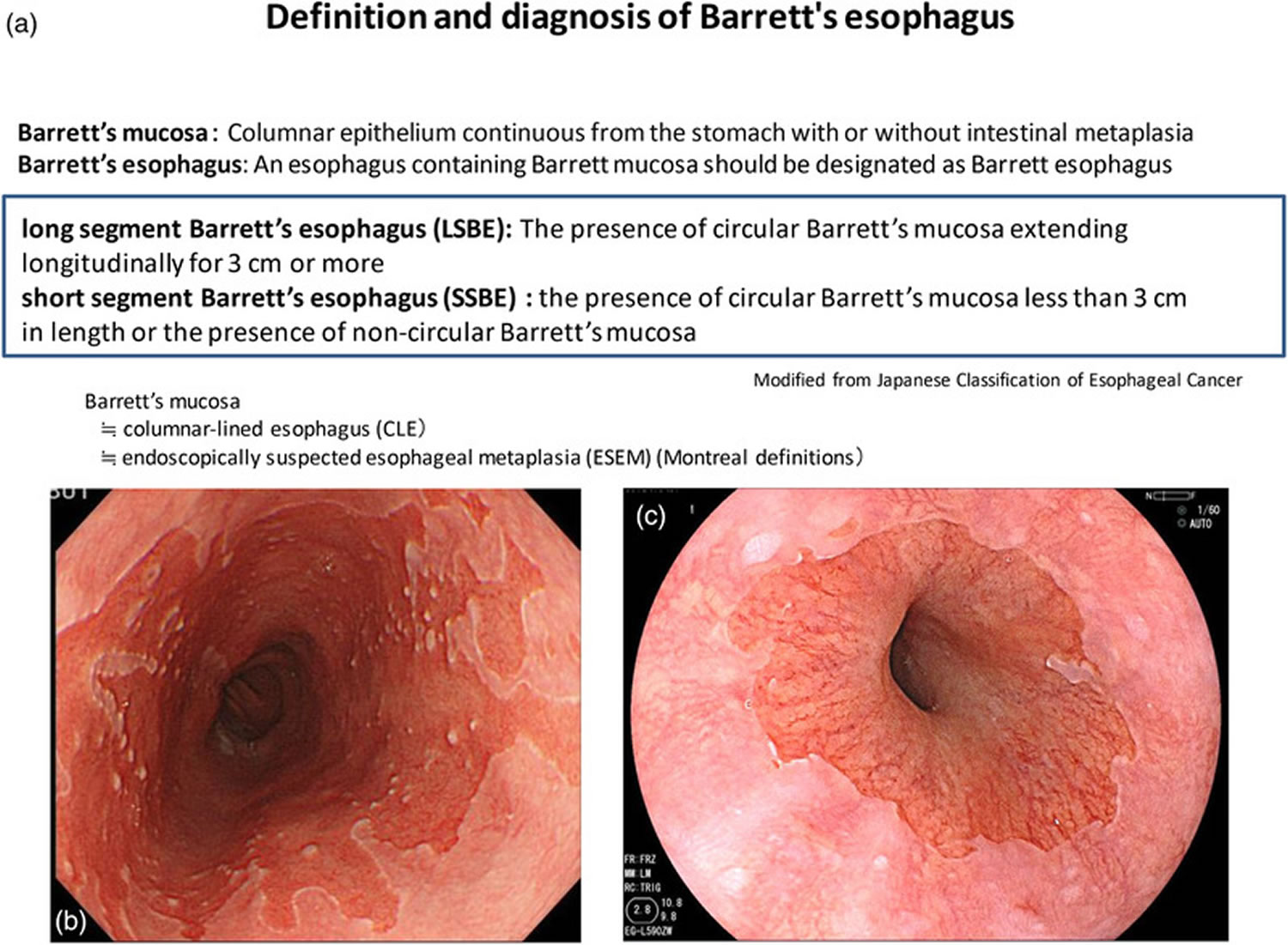

Barrett’s esophagus is defined as the presence of a specialized columnar epithelium with intestinal metaplasia with goblet cells 2. According to the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines, Barrett’s esophagus is diagnosed by the presence of intestinal metaplasia on biopsy in addition to the presence of columnar epithelium of at least 1 cm in the esophagus, generally described as “salmon-pink” colored mucosa extending more than 1 cm proximal to the gastroesophageal junction 3. However, the British Society of Gastroenterology 4, as well as the GERD Society Study Committee in Japan 5, do not require the presence of goblet cells to diagnose Barrett’s esophagus and base the diagnosis solely on the presence of columnar metaplasia. Due to the controversy over the significance of goblet cells, another alternative classification has been proposed, which allows the pathologist to state that there is columnar metaplasia and then further specify whether goblet cells are present or are not present. To maximize the possibility of finding Barrett’s esophagus, dysplasia, and/or carcinoma, a minimum of 8 biopsies is recommended by the American College of Gastroenterology. The Prague C & M criteria are recommended for endoscopic grading of Barrett’s esophagus, with the most proximal extent of circumferential columnar mucosa from the gastroesophageal (GE) junction being the C value, and the maximal extent of non-circumferential columnar mucosa above the gastroesophageal (GE) junction being the M value 6.

The development of Barrett’s esophagus is thought to be related to the reflux of gastric acid and bile into the esophagus and the presence of mucosal damage associated with reflux esophagitis 7. In fact, studies using esophageal pH monitoring have reported that acid exposure time in the esophagus is associated with the presence and length of Barrett’s esophagus 8. Furthermore, bilirubin exposure time in the esophagus is associated with the presence and length of Barrett’s esophagus 9. It has also been shown that the combination of gastric and bile acids further increases the risk of developing Barrett’s esophagus 10. However, why Barrett’s esophagus develops in some patients with GERD and not in others remains unclear 11.

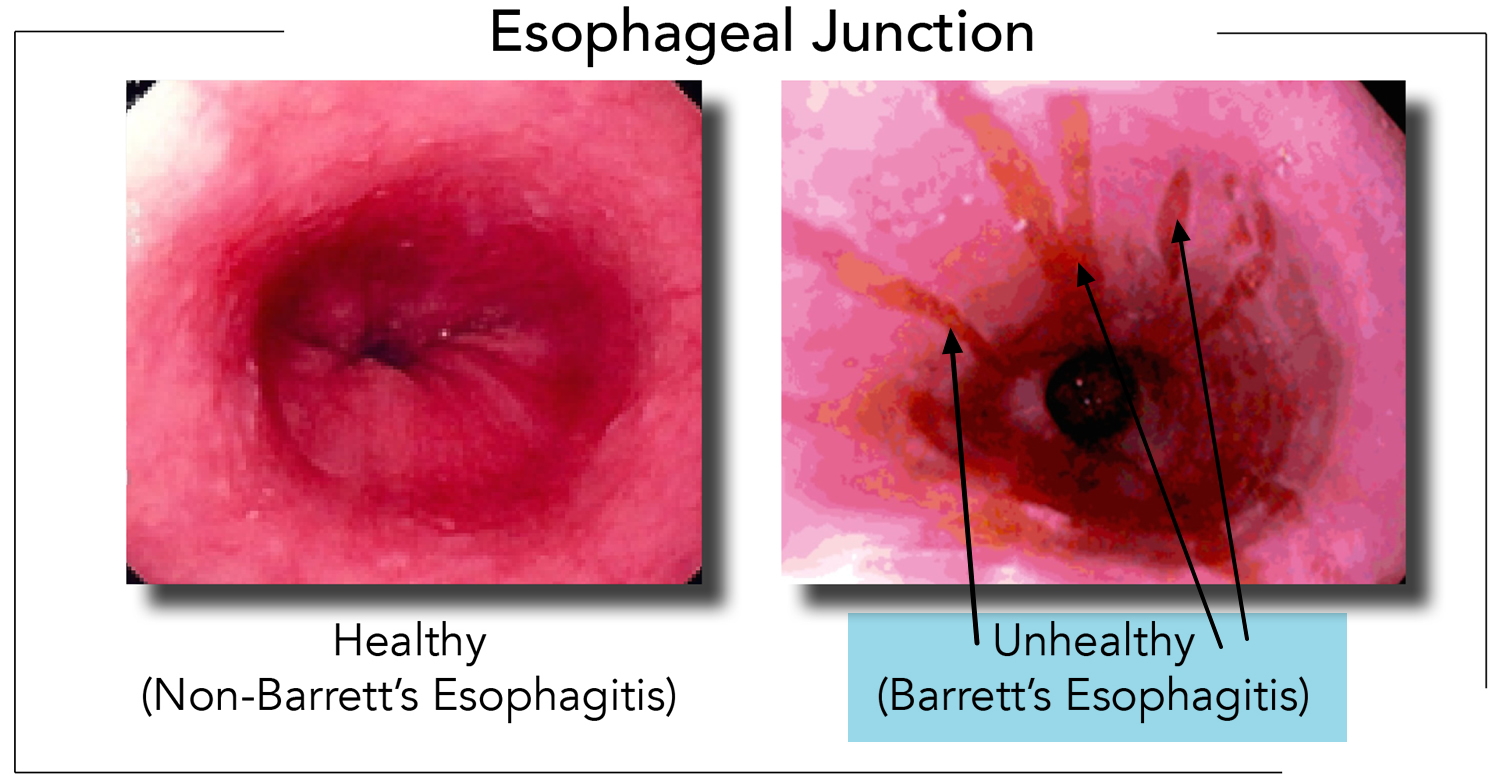

In order to understand Barrett’s esophagus, it is useful to understand the normal appearance of the esophagus. In the normal esophagus, the tissue lining appears pale pink and smooth 12. These flat square cells, called “squamous” (Latin for square) cells, make up the normal lining of the esophagus. See Figures 2 and 3.

In contrast, Barrett’s esophagus is a salmon-colored lining in the esophagus (see Figures 3 and 4), made up of cells that are similar to cells found in the small intestine and are called “specialized intestinal metaplasia.”

The reason Barrett’s esophagus is important is because people who have it have a small increased risk of developing esophageal cancer 12. Barrett’s esophagus and heartburn symptoms are associated with a specific type of esophageal cancer called “esophageal adenocarcinoma.” However, cancer is not common 1.

More than 95% of patients with Barrett’s esophagus do not develop cancer. Between 1 and 5 people out of 100 (1–5%) with Barrett’s esophagus will develop esophageal cancer 13. People with Barrett’s esophagus are at a much higher risk than people without this condition to develop adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Still, most people with Barrett’s esophagus do not get esophageal cancer.

Factors that increase your risk of Barrett’s esophagus include:

- Family history. Your odds of having Barrett’s esophagus increase if you have a family history of Barrett’s esophagus or esophageal cancer.

- Being male. Men are far more likely to develop Barrett’s esophagus.

- Being white. White people have a greater risk of the disease than do people of other races.

- Age. Barrett’s esophagus can occur at any age but is more common in adults over 50.

- Chronic heartburn and acid reflux. Having gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) that doesn’t get better when taking medications known as proton pump inhibitors or having GERD that requires regular medication can increase the risk of Barrett’s esophagus.

- Current or past smoking.

- Being overweight. Body fat around your abdomen further increases your risk.

The development of Barrett’s esophagus is most often attributed to long-standing gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which may include these signs and symptoms:

- Frequent heartburn and regurgitation of stomach contents

- Difficulty swallowing food

- Less commonly, chest pain

Curiously, approximately half of the people diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus report little if any symptoms of acid reflux. So, you should discuss your digestive health with your doctor regarding the possibility of Barrett’s esophagus.

Typically, before esophageal adenocarcinoma develops, precancerous cells appear in the Barrett’s tissue. Doctors call this pre-cancerous condition dysplasia and classify the dysplasia as low grade or high grade (see Figures 6 and 7 below). Dysplasia is graded by how abnormal the cells look under the microscope. Low-grade dysplasia looks more like normal cells, while high-grade dysplasia is more abnormal. High-grade dysplasia is linked to the highest risk of cancer. Barrett’s esophagus is best managed by doctors with an interest in this disease, including gastroenterologists, esophagus surgeons and gastroenterology pathologists.

Studies indicate the absolute annual risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus is 0.1 to 0.5% per year, a highly variable 1 to 43% per year for low-grade dysplasia, and 23-60% per year for high-grade dysplasia. A greater extent of dysplasia has a significantly higher risk of cancer as well as the presence of an endoscopic abnormality 14, 15.

In January 2016, the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) published its new clinical guideline for the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s esophagus 2. The American College of Gastroenterology now recommends screening for Barrett’s esophagus in men with at least five years of chronic GERD symptoms who also have at least two additional risk factors including greater than 50 years of age, history of smoking, white ethnicity, central obesity, or a confirmed family history of Barrett’s esophagus. The current recommendation for surveillance is four-quadrant biopsies every 2 cm (or 1 cm in known or suspected dysplasia) followed by biopsy of mucosal irregularity (nodules, ulcers, or other visible lesions) performed at 3- to 5-year intervals. Due to the extremely low prevalence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in women, this population has no indications for screening except for the presence of multiple risk factors 16, 17.

Figure 1. Esophagus

Figure 2. Barrett’s esophagus

Figure 3. Barrett’s esophagus microscopic view showing changes in the lining of the esophagus

Figure 4. Barrett’s esophagus endoscopic view (as seen by your gut specialist)

Figure 5. Barrett’s esophagus

Footnotes: Definition and diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus according to the Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer. (a) Definition and diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus. (b) Long‐segment Barrett’s esophagus (LSBE). (c) Short‐segment Barrett’s esophagus (SSBE)

[Source 7 ]What is the risk of getting esophageal cancer?

Doctors now know why patients with Barrett’s esophagus have a low risk of esophageal cancer. A person with Barrett’s esophagus has less than a 1 in 200 chance per year of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma 12. The overall risk of cancer may increase as the years go by, but more than 90% of people with Barrett’s esophagus WILL NOT develop cancer 12. Therefore, Barrett’s esophagus is a condition that you need to know about and take care of if you have it. However, the vast majority of patients with Barrett’s esophagus will never get cancer.

When should you see a doctor about Barrett’s esophagus ?

You should ask a doctor about Barrett’s esophagus if you have the risk factors listed earlier (male sex, age 50 or over, Caucasian ethnic group, gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) symptoms of longer than 10 years’ duration). If you have alarm symptoms such as trouble swallowing, losing weight without trying, blood in your stool, vomiting, persistent symptoms despite medical therapy, or new chest pain, you should discuss your symptoms with your doctor and have an endoscopic examination.

How common is Barrett’s esophagus?

Barrett’s esophagus is more commonly seen in people who have frequent, persistent heartburn or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms include heartburn (burning under your breast bone) that may wake you up at night, occur after meals or in between, and may temporarily improve with antacids. Acid regurgitation, or the experience of sour or bitter-tasting fluid coming back up into your mouth, is also a gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptom. Some people do not have any of these symptoms and are still at risk of developing Barrett’s esophagus.

What type of tests are needed to diagnose Barrett’s esophagus?

Endoscopy is the test of choice for Barrett’s esophagus. During endoscopy, a thin tube with a light and camera on the end are run through your mouth, down your throat and into your stomach. During the endoscopy, your doctor may take biopsies (tissue samples) from different parts of the food pipe. Biopsies, meaning small pieces of tissue can be collected to look at under the microscope. Normal esophagus tissue appears pale and glossy. In Barrett’s esophagus, the tissue appears red and velvety.

During endoscopy, your doctor will get multiple biopsies every 1 to 2 cm (one half to one inch) along the length of your Barrett’s esophagus segment. How the biopsies look on a microscope slide influences your management.

Your doctor may recommend a follow-up endoscopy to look for cell changes that indicate cancer. People with Barrett esophagus are recommended to have follow-up endoscopy every 3 to 5 years, or more if abnormal cells are found.

An upper gastrointestinal barium study can be helpful in finding strictures (areas of narrowing), usually causing trouble swallowing. Barium studies are not useful for diagnosing Barrett’s esophagus, because it is a diagnosis that requires biopsies of the tissues to make.

Barrett’s esophagus causes

The exact cause of Barrett’s esophagus isn’t known. While many people with Barrett’s esophagus have long-standing GERD, many have no reflux symptoms, a condition often called “silent reflux.”

Whether this acid reflux is accompanied by GERD symptoms or not, stomach acid and chemicals wash back into the esophagus, damaging esophagus tissue and triggering changes to the lining of the swallowing tube, causing Barrett’s esophagus.

When you eat, food passes from your throat to your stomach through the esophagus. The esophagus is also called the food pipe or swallowing tube. A ring of muscle fibers in the lower esophagus keeps stomach contents from moving backward.

If these muscles do not close tightly, harsh stomach acid can leak into the esophagus. This is called reflux or gastroesophageal reflux (GERD). It may cause tissue damage over time. The lining becomes similar to that of the stomach.

Barrett’s esophagus occurs more often in men than women. People who have had gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) for a long time are more likely to have this condition.

The development of Barrett’s esophagus is thought to be related to the reflux of gastric acid and bile into the esophagus and the presence of mucosal damage associated with reflux esophagitis 7. In fact, studies using esophageal pH monitoring have reported that acid exposure time in the esophagus is associated with the presence and length of Barrett’s esophagus 8. Furthermore, bilirubin exposure time in the esophagus is associated with the presence and length of Barrett’s esophagus 9. It has also been shown that the combination of gastric and bile acids further increases the risk of developing Barrett’s esophagus 10. However, why Barrett’s esophagus develops in some patients with GERD and not in others remains unclear 11.

Barrett’s esophagus risk factors

Factors that increase your risk of Barrett’s esophagus include:

- Age (age 50 or over). Barrett’s esophagus can occur at any age but is more common in adults over 50.

- Male sex. Men are far more likely to develop Barrett’s esophagus.

- Caucasian ethnicity. White people have a greater risk of the disease than do people of other races.

- Family history. Your odds of having Barrett’s esophagus increase if you have a family history of Barrett’s esophagus or esophageal cancer.

- Chronic heartburn and acid reflux. Heartburn symptoms of longer than 10 years duration are risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus.

- Having GERD that doesn’t get better when taking medications known as proton pump inhibitors or having GERD that requires regular medication can increase the risk of Barrett’s esophagus.

- Heartburn, tobacco smoking (current or past smoking), and obesity or being overweight are risk factors for developing esophageal carcinoma.

Tobacco use (especially chewing tobacco) and alcohol consumption are much stronger risk factors for a different type of cancer: squamous cell cancer of the esophagus. Tobacco slightly increases a person’s chance of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma. Obesity specifically high levels of belly fat and smoking also increase your chances of developing Barrett’s esophagus.

Most people with Barrett’s esophagus are in their 60’s at the time of diagnosis 12. It is thought that most people who are diagnosed with Barrett’s have had it for 10 to 20 years before diagnosis.

Men are 3 to 4 times more likely to have Barrett’s esophagus compared to women. Caucasians are about 10 times more likely to have Barrett’s esophagus than persons of African American ethnic background.

Although people who experience weekly heartburn or acid regurgitation are 64 times more likely to get esophageal adenocarcinoma than people who have never experienced these symptoms, 40% of people with esophageal adenocarcinoma deny ever experiencing heartburn. Why these people developed esophageal adenocarcinoma remains a mystery 12.

Some studies suggest that your genetics, or inherited genes, may play a role in whether or not you develop Barrett’s esophagus.

Barrett’s esophagus symptoms

Barrett’s esophagus itself does not cause symptoms. The acid reflux that causes Barrett’s esophagus often leads to symptoms of heartburn. While many people with Barrett’s esophagus have long-standing GERD, many have no reflux symptoms, a condition often called “silent reflux.”

The development of Barrett’s esophagus is most often attributed to long-standing GERD, which may include these signs and symptoms:

- Frequent heartburn and regurgitation of stomach contents

- Difficulty swallowing food

- Less commonly, chest pain

Curiously, approximately half of the people diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus report little if any symptoms of acid reflux. So, you should discuss your digestive health with your doctor regarding the possibility of Barrett’s esophagus.

The classic picture of a patient with Barrett esophagus is a middle-aged (55 years of age) white man with a chronic history of gastroesophageal reflux—for example, acid regurgitation, and, occasionally, dysphagia 18. Some patients, however, deny having any symptoms.

Barrett’s esophagus screening

The American College of Gastroenterology says screening may be recommended for men who have had GERD symptoms at least weekly that don’t respond to treatment with proton pump inhibitor medication, and who have at least two more risk factors, including:

- Having a family history of Barrett’s esophagus or esophageal cancer

- Being male

- Being white

- Being over 50

- Being a current or past smoker

- Having a lot of abdominal fat

While women are significantly less likely to have Barrett’s esophagus, women should be screened if they have uncontrolled reflux or have other risk factors for Barrett’s esophagus.

Barrett’s esophagus prevention

Diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux (GERD)

Diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) may prevent Barrett esophagus.

The risk factors for gastroesophageal reflux (GERD) include:

- Use of alcohol (possibly)

- Hiatal hernia (a condition in which part of the stomach moves above the diaphragm, which is the muscle that separates the chest and abdominal cavities)

- Obesity

- Pregnancy

- Scleroderma

- Smoking

Heartburn and gastroesophageal reflux can be brought on or made worse by pregnancy.

Symptoms can also be caused by certain medicines, such as:

- Anticholinergics (for example, seasickness medicine)

- Bronchodilators for asthma

- Calcium channel blockers for high blood pressure

- Dopamine-active drugs for Parkinson disease

- Progestin for abnormal menstrual bleeding or birth control

- Sedatives for insomnia or anxiety

- Tricyclic antidepressants

Talk to your health care provider if you think one of your medicines may be causing heartburn. Never change or stop taking a medicine without first talking to your provider.

Barrett’s esophagus diet

Can your diet help prevent Barrett’s esophagus?

Researchers have not found that diet and nutrition play an important role in causing or preventing Barrett’s esophagus 19.

If you have gastroesophageal reflux or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), you can prevent or relieve your symptoms by changing your diet. Dietary changes that can help reduce your symptoms include:

- decreasing fatty foods

- eating small, frequent meals instead of three large meals

Avoid eating or drinking the following items that may make gastroesophageal reflux or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) worse:

- chocolate

- coffee

- peppermint

- greasy or spicy foods

- tomatoes and tomato products

- citrus juices

- alcoholic drinks

- smoking

Barrett’s esophagus diagnosis

Endoscopy is the test of choice for Barrett’s esophagus. During endoscopy, a thin tube with a light and camera on the end are run through your mouth, down your throat and into your stomach. During the endoscopy, your doctor may take biopsies (tissue samples) from different parts of the food pipe. Biopsies, meaning small pieces of tissue can be collected to look at under the microscope. Normal esophagus tissue appears pale and glossy. In Barrett’s esophagus, the tissue appears red and velvety.

During endoscopy, your doctor will get multiple biopsies every 1 to 2 cm (one half to one inch) along the length of your Barrett’s esophagus segment. How the biopsies look on a microscope slide influences your management.

Your doctor may recommend a follow-up endoscopy to look for cell changes that indicate cancer. People with Barrett esophagus are recommended to have follow-up endoscopy every 3 to 5 years, or more if abnormal cells are found.

An upper gastrointestinal barium study can be helpful in finding strictures (areas of narrowing), usually causing trouble swallowing. Barium studies are not useful for diagnosing Barrett’s esophagus, because it is a diagnosis that requires biopsies of the tissues to make.

Barrett’s esophagus is defined as a condition in which the mucosa of the lower esophagus has been replaced by a continuous columnar epithelium from the stomach. To endoscopically diagnose Barrett’s esophagus, the gastroesophageal (GE) junction must be identified. According to the Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer edited by the Japan Esophageal Society, the gastroesophageal (GE) junction is defined as the lower margin of palisading small vessels in the lower esophagus on endoscopy, or if the palisading small vessels are unclear, the oral margin of the longitudinal folds of the greater curvature of the stomach is defined as the gastroesophageal (GE) junction 5. On the other hand, in western countries, “the upper margin of the gastric mucosal fold” is mainly used as the definition of gastroesophageal (GE) junction, but the oral edge of the gastric mucosal fold changes easily depending on airflow and the degree of inspiration 7.

Once the gastroesophageal (GE) junction is determined, Barrett’s esophagus can easily be diagnosed, but it is important to note the difference in definitions between Japan and the West. In most western countries, Barrett’s esophagus is defined as the presence of a specialized columnar epithelium with intestinal metaplasia with goblet cells because of the increased risk of carcinogenesis 2. According to the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines, Barrett’s esophagus is diagnosed by the presence of intestinal metaplasia on biopsy in addition to the presence of columnar epithelium of at least 1 cm in the esophagus (Table 1) 3. On the other hand, in Japan, the definition of Barrett’s mucosa by the Japan Esophageal Society is a columnar epithelium continuous from the stomach with or without intestinal metaplasia, and an esophagus containing Barrett’s mucosa should be designated as Barrett’s esophagus. The definition of long‐segment Barrett’s esophagus (LSBE) is the presence of circular Barrett’s mucosa extending longitudinally for 3 cm or more, and the presence of circular Barrett mucosa less than 3 cm in length or the presence of non‐circular Barrett’s mucosa is designated as short‐segment Barrett’s esophagus (SSBE) (Figure 5). On the other hand, in western countries, Barrett’s esophagus with a maximum length of 3 cm is defined as an long‐segment Barrett’s esophagus (LSBE).

Table 1. Diagnostic criteria for Barrett’s esophagus in different countries

| Guidelines | Length criteria | Histology criteria |

|---|---|---|

| American Gastroenterological Association | Any extent | Intestinal metaplasia |

| American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy | None | Intestinal metaplasia |

| British Society of Gastroenterology | ≥ 1 cm | Columnar epithelium |

| Australia | Any extent | Intestinal metaplasia |

| American College of Gastroenterology | ≥ 1 cm | Intestinal metaplasia |

| European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy | ≥ 1 cm | Intestinal metaplasia |

| Asian Pacific Association of Gastroenterology | ≥ 1 cm | Columnar epithelium |

Determining the degree of tissue change

A doctor who specializes in examining tissue in a laboratory (pathologist) determines the degree of dysplasia in your esophagus cells. Because it can be difficult to diagnose dysplasia in the esophagus, it’s best to have two pathologists — with at least one who specializes in gastroenterology pathology — agree on your diagnosis. Your tissue may be classified as:

- No dysplasia, if Barrett’s esophagus is present but no precancerous changes are found in the cells.

- Low-grade dysplasia, if cells show small signs of precancerous changes.

- High-grade dysplasia, if cells show many changes. High-grade dysplasia is thought to be the final step before cells change into esophageal cancer.

Barrett’s esophagus treatment

Your doctor will talk about the best treatment options for you based on your overall health, whether you have dysplasia and its severity. Treatment options include medicines for gastroesophageal reflux (GERD), endoscopic ablative therapies, endoscopic mucosal resection, and surgery.

The key to the management of Barrett’s esophagus is the level of dysplasia that the biopsies show. “Dysplasia” is how much precancerous changes the cells have. “No Dysplasia” means that the Barrett’s cells show no precancerous changes. Low-grade dysplasia means that the cells show some of the early characteristics of cancer. High-grade dysplasia means that the cells show more advanced changes of cancer. The worse the dysplasia, the higher the risk that the Barrett’s esophagus will go on to cancer.

All of your cells are programmed to die. You are constantly making new cells while old cells slough off. For example, dandruff is old dead scalp cells that have dried up and flaked off. Just like your skin on the outside of your body, the lining of the esophagus is skin on the inside of your body. Cells keep their DNA in their nucleus. Cancer is DNA that has lost control of how fast the cells divide, or how quickly they die. In cancer, cells grow and grow without dying.

When cells are changing from normal to cancer, they go through the steps of dysplasia outlined above.

Periodic surveillance endoscopy

Your doctor may use upper gastrointestinal endoscopy with a biopsy periodically to watch for signs of cancer development 20, 21. Doctors call this approach surveillance.

Experts aren’t sure how often doctors should perform surveillance endoscopies. Talk with your doctor about what level of surveillance is best for you. Your doctor may recommend endoscopies more frequently if you have high-grade dysplasia rather than low-grade or no dysplasia.

Table 2. Guidelines for Barrett’s esophagus surveillance in different countries

| Guidelines | Length‐based criteria | Interval |

|---|---|---|

| American Gastroenterological Association | No | 3–5 years |

| American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy | No | 3–5 years |

| British Society of Gastroenterology | <3 cm with intestinal metaplasia | 3–5 years |

| ≥3 cm with intestinal metaplasia | 2–3 years | |

| Australia | <3 cm | 3–5 years |

| >3 cm | 2–3 years | |

| American College of Gastroenterology | No | 3–5 years |

| European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy | ≥1 cm and <3 cm | 5 years |

| ≥3 cm and <10 cm | 3 years | |

| ≥10 cm | Expert center management | |

| Asian Pacific Association of Gastroenterology | No | 3–5 years |

No dysplasia

If a diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus is made, ideally there should be NO dysplasia. Most people with Barrett’s esophagus and no dysplasia will need to undergo future endoscopies to assure there is no progression of the condition. When the next endoscopy occurs is usually based on recommendations by groups of experts whose opinion is endorsed the American College of Gastroenterology. Follow up endoscopy for Barrett’s esophagus without dysplasia is usually recommended at 3-5 years, but your doctor will help decide what is most appropriate for you.

Your doctor will likely recommend:

- Periodic endoscopy to monitor the cells in your esophagus. If your biopsies show no dysplasia, you’ll probably have a follow-up endoscopy in one year and then every three to five years if no changes occur.

- Treatment for GERD. Medication and lifestyle changes can ease your signs and symptoms. Surgery or endoscopy procedures to correct a hiatal hernia or to tighten the lower esophageal sphincter that controls the flow of stomach acid may be an option.

Figure 6. Barrett’s esophagus “NO dysplasia”

Footnote: In biopsies with no dysplasia, the nuclei are small, organized and located at the base (bottom) of the Barrett’s cell.

[Source 12 ]Low-grade dysplasia

Low-grade dysplasia is considered the early stage of precancerous changes. Low-grade dysplasia is where the nuclei are still small but somewhat disorganized (Figure 6). If low-grade dysplasia is found, it should be verified by an experienced pathologist, because low-grade dysplasia can be a hard diagnosis for a pathologist to make correctly, and sometimes there is disagreement among pathologists that might require yet another opinion to resolve.

For low-grade dysplasia, your doctor may recommend another endoscopy in six months, with additional follow-up every six to 12 months.

But, given the risk of esophageal cancer, treatment may be recommended if the diagnosis is confirmed. Preferred treatments include:

- Endoscopic resection, which uses an endoscope to remove damaged cells to aid in the detection of dysplasia and cancer.

- Radiofrequency ablation, which uses heat to remove abnormal esophagus tissue. Radiofrequency ablation may be recommended after endoscopic resection.

- Cryotherapy, which uses an endoscope to apply a cold liquid or gas to abnormal cells in the esophagus. The cells are allowed to warm up and then are frozen again. The cycle of freezing and thawing damages the abnormal cells.

If significant inflammation of the esophagus is present at initial endoscopy, another endoscopy is performed after you’ve received three to four months of treatment to reduce stomach acid.

If the diagnosis of low-grade dysplasia is confirmed, it is recommended that otherwise healthy people consider getting endoscopic treatment to get rid of their Barrett’s esophagus. The most common way of doing this is a process called radiofrequency ablation. In radiofrequency ablation treatments, heat is applied to the precancerous tissue to kill those cells so that normal healthy cells can grow there instead. Studies demonstrate that these treatments can lower the patient’s chance of ever getting cancer. Another acceptable option if low-grade dysplasia is found is to continue to perform endoscopies to monitor the condition, without doing any ablation treatments. If this option is selected, the repeat endoscopy is usually performed 1 year after the first one.

Figure 7. Barrett’s esophagus “Low grade dysplasia”

High-grade dysplasia

High-grade dysplasia is generally thought to be a precursor to esophageal cancer (Figure 7). If diagnosed with high-grade dysplasia the biopsies should be examined again by a pathologist who specializes in diseases of the esophagus. For this reason, your doctor may recommend endoscopic resection, radiofrequency ablation or cryotherapy. Another option may be surgery, which involves removing the damaged part of your esophagus and attaching the remaining portion to your stomach.

Recurrence of Barrett’s esophagus is possible after treatment. Ask your doctor how often you need to come back for follow-up testing. If you have treatment other than surgery to remove abnormal esophageal tissue, your doctor is likely to recommend lifelong medication to reduce acid and help your esophagus heal.

Figure 8. Barrett’s esophagus “High grade dysplasia”

Lifestyle Modification

In order to decrease the amount of gastric contents that reach the lower esophagus, certain simple guidelines should be followed:

- Raise the Head of the Bed. The simplest method is to use a 4″ x 4″ piece of wood to which two jar caps have been nailed an appropriate distance apart to receive the legs or casters at the upper end of the bed. Failure to use the jar caps inevitably results in the patient being jolted from sleep as the upper end of the bed rolls off the 4″ x 4″.

- Alternatively, one may use an under-mattress foam wedge to elevate the head about 6-10 inches. Pillows are not an effective alternative for elevating the head in preventing reflux.

- Change Eating and Sleeping Habits. Avoid lying down for two hours after eating. Do not eat for at least two hours before bedtime. This decreases the amount of stomach acid available for reflux.

- Avoid Tight Clothing. Reduce your weight if obesity contributes to the problem.

- Avoid foods and beverages that contribute to heartburn: chocolate, fats, coffee, peppermint, greasy or spicy foods, citrus juice, tomato products, peppers and alcoholic beverages.

- Avoid drugs such as aspirin, ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin), or naproxen (Aleve, Naprosyn). Take acetaminophen (Tylenol) to relieve pain.

- Stop smoking. Tobacco inhibits saliva, which is the body’s major buffer. Tobacco may also stimulate stomach acid production and relax the muscle between the esophagus and the stomach, permitting acid reflux to occur.

- Reduce weight if too heavy. Obesity is linked to GERD, so maintaining a healthy body weight may help prevent the condition.

- Do not eat 2-3 hours before sleep.

- For infrequent episodes of heartburn, take an over-the-counter antacid or an H2 blocker, some of which are now available without a prescription.

Acid suppression medications

If you have Barrett’s esophagus and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), your doctor will treat you with acid-suppressing medicines called proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). These medicines can prevent further damage to your esophagus and, in some cases, heal existing damage.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) include:

- omeprazole (Prilosec, Zegerid)

- lansoprazole (Prevacid)

- pantoprazole (Protonix)

- rabeprazole (AcipHex)

- esomeprazole (Nexium)

- dexlansoprazole (Dexilant)

All of these medicines are available by prescription. Omeprazole and lansoprazole are also available in over-the-counter strength.

Your doctor may consider anti-reflux surgery if you have GERD symptoms and don’t respond to medicines. However, research has not shown that medicines or surgery for GERD and Barrett’s esophagus lower your chances of developing dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Endoscopic ablative therapies

Endoscopic ablative therapies use different techniques to destroy the dysplasia in your esophagus. The goal of ablative therapy is to destroy the Barrett epithelium to a sufficient depth to eliminate the intestinal metaplasia and allow regrowth of squamous epithelium. A number of modalities have been tried, usually in combination with medical or surgical therapy because successful ablation appears to require an antacid environment.

A doctor, usually a gastroenterologist or surgeon, performs these procedures at certain hospitals and outpatient centers. You will receive local anesthesia and a sedative.

Ablative therapy is emerging as a viable alternative to surgical resection or esophagectomy for patients with high-grade dysplasia in Barrett esophagus. In fact, in most major medical centers ablation is first-line therapy. A study by Prasad found that the 5-year survival rate for patients with high-grade dysplasia in Barrett esophagus who were treated with photodynamic therapy (PDT) and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) was comparable to that of patients treated with esophagectomy (surgery to remove some or most of the esophagus) 22.

A retrospective cohort study of 166 patients with dysplastic Barrett esophagus showed that endoluminal therapy combining endoscopic mucosal resection and ablation is a safe and effective treatment for Barrett esophagus 23.

The most common ablative procedures are the following:

Radiofrequency ablation

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) uses radio waves to kill precancerous and cancerous cells in the Barrett’s tissue. An electrode mounted on a balloon or an endoscope creates heat to destroy the Barrett’s tissue and precancerous and cancerous cells.

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is FDA approved for eradication of high-grade dysplasia in Barrett esophagus. It is also a treatment option for low-grade dysplasia in Barrett esophgus, provided the risks and benefits are thoroughly discussed with the patient 24.

Complications of radiation ablation may include:

- chest pain

- cuts in the lining of your esophagus

- strictures

Clinical trials have shown that complications are less common with radiofrequency ablation compared with photodynamic therapy (PDT).

Shaheen et al 25 demonstrated that radiofrequency ablation (RFA) was associated with a high rate of complete eradication of dysplasia and intestinal metaplasia and a reduced risk of disease progression in patients with dysplastic Barrett esophagus. In the study, complete eradication occurred in 90.5% of patients with low-grade dysplasia who received radiofrequency ablation, compared with 22.7% of patients in the control group, who underwent a sham procedure. Among patients with high-grade dysplasia, complete eradication occurred in 81% of those in the ablation group, whereas complete eradication occurred in only 19% of patients in the control group 25.

Patients in the ablation group had less disease progression than did those in the control group (3.6% vs 16.3%, respectively) and fewer cancers than did patients in the control group (1.2% vs 9.3%, respectively).

In a randomized study of 136 patients with Barrett esophagus and low-grade dysplasia, Phoa et al 26 found that in comparison with endoscopic surveillance, endoscopic radiofrequency ablation (RFA) significantly reduced the rate of neoplastic progression to high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma.

Over 3 years of follow-up, radiofrequency ablation (RFA) reduced the risk of progression to high-grade dysplasia or adenocarcinoma from 26.5% to 1.5% and lowered the risk of progression to adenocarcinoma from 8.8% to 1.5% 26. Among patients in the ablation group, the rate of complete eradication was 92.6% for dysplasia and 88.2% for intestinal metaplasia, compared with 27.9% for dysplasia and 0% for intestinal metaplasia among patients in the surveillance group.

Use of endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) before radiofrequency ablation (RFA) appears to significantly reduce the risk of treatment failure for Barrett esophagus–associated dysplasia and Barrett esophagus–associated intramucosal adenocarcinoma, whereas a significant predictor of treatment failure appears to be the presence of intramucosal adenocarcinoma involving 50% or more of the columnar metapastic area on index examination 27.

Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) uses a light-activated chemical called porfimer (Photofrin), an endoscope, and a laser to kill precancerous cells in your esophagus. A doctor injects porfimer into a vein in your arm, and you return 24 to 72 hours later to complete the procedure.

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) involves the use of a a light-activated chemical called porfimer (Photofrin) that accumulates in tissue and induces local necrosis through the production of intracellular free radicals following exposure to light at a certain wavelength. Typically, a hematoporphyrin is used as the photosensitizing agent because it has a greater affinity for neoplastic tissue.

Another agent, 5-aminolevulinic acid (ALA), which induces endogenous protoporphyrin IX and has selectivity for the mucosa over deeper submucosal layers, has also been used. The results have been promising for the regression of Barrett esophagus, as well as for the treatment of dysplasia and superficial carcinoma.

Using photodynamic therapy (PDT) to treat 100 patients—including 73 with high-grade dysplasia and 13 with superficial adenocarcinoma, Overholt et al found that Barrett mucosa was completely eliminated in 43 patients and dysplasia was eliminated in 78 patients 28.

Other studies have shown similar response rates, but Barrett epithelium beneath the superficial squamous layer has been observed, indicating that deeper-placed pluripotent cells may be preserved. Additionally, photodynamic therapy (PDT) is an expensive and time-consuming endeavor, and early use was complicated by esophageal stricture requiring dilation in 58% of patients. Photodynamic therapy (PDT) has been largely replaced by radiofrequency ablation (RFA) in most medical centers performing ablation.

Complications of photodynamic therapy (PDT) may include:

- sensitivity of your skin and eyes to light for about 6 weeks after the procedure

- burns, swelling, pain, and scarring in nearby healthy tissue

- coughing, trouble swallowing, stomach pain, painful breathing, and shortness of breath.

Endoscopic mucosal resection

In endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), your doctor lifts the Barrett’s tissue, injects a solution underneath or applies suction to the tissue, and then cuts the tissue off. The doctor then removes the tissue with an endoscope. Gastroenterologists perform this procedure at certain hospitals and outpatient centers. You will receive local anesthesia to numb your throat and a sedative to help you relax and stay comfortable.

Before performing an endoscopic mucosal resection for cancer, your doctor will do an endoscopic ultrasound.

Endoscopic mucosal resection complications can include bleeding or tearing of your esophagus. Doctors sometimes combine endoscopic mucosal resection with photodynamic therapy.

Surgery

Surgery called esophagectomy is an alternative to endoscopic therapies. Many doctors prefer endoscopic therapies because these procedures have fewer complications.

Esophagectomy is the surgical removal of the affected sections of your esophagus. After removing sections of your esophagus, a surgeon rebuilds your esophagus from part of your stomach or large intestine. The surgery is performed at a hospital. You’ll receive general anesthesia, and you’ll stay in the hospital for 7 to 14 days after the surgery to recover.

Surgery may not be an option if you have other medical problems. Your doctor may consider the less-invasive endoscopic treatments or continued frequent surveillance instead.

Barrett’s esophagus prognosis

Barrett esophagus is left untreated, it can develop into an esophageal adenocarcinoma 29. However, the risk of progression is very slow, and most patients with Barrett esophagus will not develop esophageal cancer, with the risk of progression to adenocarcinoma of the esophagus being estimated at approximately 0.3% to 0.5% per year in patients without dysplasia (nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus) on initial surveillance biopsies 30. Therefore, control of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms along with periodic surveillance with appropriate technique is recommended in most patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus 30. Certain patients with nondysplastic Barrett’s esophagus remain at high risk for neoplastic progression and consideration may be given to endoscopic eradication therapy in these high-risk groups.

It should be noted that the number of cases of esophageal adenocarcinoma has steadily increased over the past three decades 31, 32, 33.

Barrett’s esophagus cancer

Esophageal cancer is cancer that starts in the esophagus — a long, hollow muscular tube that runs from your throat to your stomach 34. Your esophagus helps move the food you swallow from the back of your throat to your stomach to be digested. You’re at greater risk for getting esophageal cancer if you smoke, drink heavily, or have acid reflux. Your risk also goes up as you age.

Esophageal cancer usually begins in the cells that line the inside of the esophagus. Esophageal cancer can occur anywhere along the esophagus. More men than women get esophageal cancer.

Esophageal cancer makes up about 1% of all cancers diagnosed in the United States, but it is much more common in some other parts of the world, such as Iran, northern China, India, and southern Africa.

Esophageal cancer is the sixth most common cause of cancer deaths worldwide. Incidence rates vary within different geographic locations. In some regions, higher rates of esophageal cancer cases may be attributed to tobacco and alcohol use or particular nutritional habits and obesity.

The American Cancer Society’s estimates for esophageal cancer in the United States for 2022 are 35, 36:

- New cases: About 20,640 new esophageal cancer cases diagnosed (16,510 in men and 4,130 in women)

- Deaths: About 16,410 deaths from esophageal cancer (13,250 in men and 3,160 in women)

- 5-Year Relative Survival: 20.6%. Relative survival is an estimate of the percentage of patients who would be expected to survive the effects of their esophageal cancer. It excludes the risk of dying from other causes. Because survival statistics are based on large groups of people, they cannot be used to predict exactly what will happen to an individual patient. No two patients are entirely alike, and treatment and responses to treatment can vary greatly.

- Esophageal cancer deaths as a percentage of All Cancer Deaths: 2.7%.

- Rate of New Cases and Deaths per 100,000: The rate of new cases of esophageal cancer was 4.2 per 100,000 men and women per year. The death rate was 3.8 per 100,000 men and women per year. These rates are age-adjusted and based on 2015–2019 cases and 2016–2020 deaths.

- Lifetime Risk of Developing Cancer: Approximately 0.5 percent of men and women will be diagnosed with esophageal cancer at some point during their lifetime, based on 2017–2019 data.

- In 2019, there were an estimated 49,084 people living with esophageal cancer in the United States.

Esophageal cancer is more common among men than among women. The lifetime risk of esophageal cancer in the United States is about 1 in 125 in men and about 1 in 417 in women 35.

Overall, the rates of esophageal cancer in the United States have been fairly stable for many years, but over the past decade they have been decreasing slightly. It is most common in whites, but is now almost equally as common in African Americans. Adenocarcinoma is the most common type of cancer of the esophagus among whites, while squamous cell carcinoma is more common in African Americans. American Indian/Alaska Natives and Hispanics have lower rates of esophageal cancer, followed by Asians/Pacific Islanders 35.

There are two main types of cancer that can occur in the esophagus 37:

- Squamous cell carcinoma. The esophagus is normally lined with squamous cells. Cancer starting in these cells is called squamous cell carcinoma. This type of cancer can occur anywhere along the esophagus, but is most common in the portion of the esophagus located in the neck region and in the upper two-thirds of the chest cavity. Squamous cell carcinoma is linked to smoking and drinking alcohol. Squamous cell carcinoma used to be the most common type of esophageal cancer in the United States. This has changed over time, and now it makes up less than half of esophageal cancers in this country.

- Adenocarcinoma. Cancers that start in gland cells (cells that make mucus) are called adenocarcinomas. This type of cancer usually occurs in the distal (lower third) part of the esophagus (lower thoracic esophagus). Before an adenocarcinoma can develop, gland cells must replace an area of squamous cells, which is what happens in Barrett’s esophagus. Having Barrett esophagus increases the risk of adenocarcinoma. This occurs mainly in the lower esophagus, which is where most adenocarcinomas start. Adenocarcinomas that start at the area where the esophagus joins the stomach (the gastroesophageal (GE) junction, which includes about the first 2 inches (5 cm) of the stomach called the cardia), tend to behave like cancers in the esophagus (and are treated like them, as well), so they are grouped with esophagus cancers. Acid reflux disease (gastroesophageal reflux disease or GERD) can develop into Barrett’s esophagus. Other risk factors include smoking, being male, or being obese.

Many people with esophageal cancer do not have signs or symptoms when the cancer first starts. Later, when the tumor gets larger, symptoms can include:

- Painful or difficult swallowing (dysphagia)

- Weight loss for no known reason

- Chest pain, pressure or burning

- Worsening indigestion or heartburn

- Hiccups

- Throwing up with streaks of blood

- A hoarse voice or cough that doesn’t go away

- Streaks of blood in mucus coughed up from the lungs

Your doctor uses imaging tests and a biopsy to diagnose esophageal cancer. Treatments include surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy.

When the cancer has not spread outside the esophagus, surgery may improve the chance of survival.

When the cancer has spread to other areas of the body, a cure is generally not possible 34. Treatment is directed toward relieving symptoms. You might also need nutritional support, since the cancer or treatment may make it hard to swallow.

Although many people with esophageal cancer will go on to die from this disease, treatment has improved and survival rates are getting better. During the 1960s and 1970s, only about 5% of patients survived at least 5 years after being diagnosed. Now, about 20% of patients survive at least 5 years after diagnosis. This number includes patients with all stages of esophageal cancer. Survival rates for people with early stage cancer are higher.

Make an appointment with your doctor if you have any persistent signs and symptoms that worry you.

You should see your doctor if you have:

- difficulty swallowing

- symptoms that are unusual for you

- symptoms that don’t go away

Your symptoms are unlikely to be cancer but it is important to get them checked by a doctor.

If you’ve been diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus, a precancerous condition caused by chronic acid reflux, your risk of esophageal cancer is higher. Ask your doctor what signs and symptoms to watch for that may signal that your condition is worsening.

If you’ve had trouble with heartburn, regurgitation and acid reflux for more than five years, then you should ask your doctor about your risk of Barrett’s esophagus.

Screening for esophageal cancer may be an option for people with Barrett’s esophagus. If you have Barrett’s esophagus, discuss the pros and cons of screening with your doctor.

Seek immediate help if you:

- Have chest pain, which may be a symptom of a heart attack

- Have difficulty swallowing

- Are vomiting red blood or blood that looks like coffee grounds

- Are passing black, tarry or bloody stools

- Are unintentionally losing weight

Esophageal cancer causes

Studies show that esophageal cancer is more commonly diagnosed in people over the age of 55 years. Less than 15% of cases are found in people younger than age 55. Men are affected twice as commonly as women. Squamous cell esophageal cancer is more common in African Americans than Caucasians. On the other hand, adenocarcinoma appears to be more common in middle-aged Caucasian men.

The exact cause is unknown; however there are well-recognized risk factors that make getting esophageal cancer more likely. In the US, alcohol, smoking and obesity are the major risk factors. Stopping drinking and smoking may reduce the chance of getting esophageal cancer as well as other types of cancers. Sometimes adenocarcinoma of the esophagus runs in families.

The risk of cancer of the esophagus is also increased by irritation of the lining of the esophagus. In patients with acid reflux, where contents from the stomach back up into the esophagus, the cells that line the esophagus can change and begin to resemble the cells of the intestine. This condition is knows as Barrett’s esophagus. Those with Barrett’s esophagus have a higher risk of developing esophageal cancer.

Less common causes of irritation can also increase the chance of developing esophageal cancer. For example, people who have swallowed caustic substances like lye can have damage to the esophagus that increases the risk of developing esophageal cancer.

Factors that cause irritation in the cells of your esophagus and increase your risk of esophageal cancer include:

- Having gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Smoking

- Having precancerous changes in the cells of the esophagus (Barrett’s esophagus)

- Being obese

- Drinking alcohol

- Having bile reflux

- Having difficulty swallowing because of an esophageal sphincter that won’t relax (achalasia)

- Having a steady habit of drinking very hot liquids

- Not eating enough fruits and vegetables

- Undergoing radiation treatment to the chest or upper abdomen

Scientists believe that some risk factors, such as the use of tobacco or alcohol, may cause esophageal cancer by damaging the DNA in cells that line the inside of the esophagus. Long-term irritation of the lining of the esophagus, as happens with reflux, Barrett’s esophagus, achalasia, Plummer-Vinson syndrome, or scarring from swallowing lye, may also lead to DNA damage.

DNA is the chemical in each of our cells that makes up your genes – the instructions for how your cells function. You usually look like your parents because they are the source of your DNA. However, DNA affects more than how you look. Some genes control when cells grow, divide into new cells, and die. Genes that help cells grow, divide, and stay alive are called oncogenes. Genes that slow down cell division or make cells die at the right time are called tumor suppressor genes. Cancers can be caused by DNA changes that turn on oncogenes or turn off tumor suppressor genes.

The DNA of esophageal cancer cells often shows changes in many different genes. However, it’s not clear if there are specific gene changes that can be found in all (or most) esophageal cancers.

Some people inherit DNA changes (mutations) from their parents that increase their risk for developing certain cancers. These are called inherited mutations. But esophageal cancer does not seem to run in families, and inherited gene mutations are not thought to be a major cause of this disease. For example:

- Tylosis with esophageal cancer (sometimes called Howel-Evans syndrome) is caused by inherited changes in the RHBDF2 gene. People with changes in this gene are more at risk of developing the squamous cell type of esophageal cancer.

- Bloom syndrome is caused by changes in the BLM gene. The BLM gene is important in making a protein that stabilizes DNA as a cell divides. Without this protein, the DNA can become damaged, which can lead to cancer. People with Bloom syndrome are at a higher risk of developing squamous cell esophageal cancer, as well as AML, ALL, and other cancers involving the lymph system. For this syndrome, an abnormal gene is usually inherited from both parents, not just one.

- Fanconi anemia is a rare syndrome that involves abnormal genes that cannot repair damaged DNA. Mutations (changes) in certain FANC genes can lead to a higher risk of many cancers including AML and squamous cell cancer of the esophagus.

- Familial Barrett’s Esophagus is a syndrome that includes families with Barrett’s esophagus and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastroesophageal (GE) junction. The exact genes associated with this are still being studied.

Special genetic tests can find some of the gene mutations linked to these inherited syndromes. If you have a family history of esophageal cancer or other symptoms linked to these syndromes, you may want to ask your doctor about genetic counseling and genetic testing. The American Cancer Society recommends discussing genetic testing with a qualified cancer genetics professional before any genetic testing is done.

Esophageal cancer prevention

To reduce your risk of cancer of the esophagus:

- DO NOT smoke.

- Limit or DO NOT drink alcoholic beverages.

- Get checked by your doctor if you have severe GERD.

- Get regular checkups if you have Barrett’s esophagus.

Avoiding tobacco and alcohol

In the United States, the most important lifestyle risk factors for cancer of the esophagus are the use of tobacco and alcohol. Each of these factors alone increases the risk of esophageal cancer many times, and the risk is even greater if they are combined. Avoiding tobacco and alcohol is one of the best ways of limiting your risk of esophageal cancer.

If you smoke, talk to your doctor about strategies for quitting. Medications and counseling are available to help you quit. If you don’t use tobacco, don’t start.

Watching your diet and body weight

Eating a healthy diet and staying at a healthy weight are also important. A diet rich in fruits and vegetables may help protect against esophageal cancer. Obesity has been linked with esophageal cancer, particularly the adenocarcinoma type, so staying at a healthy weight may also help limit the risk of this disease.

Getting treated for gastroesophageal reflux or Barrett’s esophagus

Treating people with reflux may help prevent Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal cancer. Often, reflux is treated using drugs called proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), such as omeprazole (Prilosec®), lansoprazole (Prevacid®), or esomeprazole (Nexium®). Surgery might also be an option for treating reflux if the reflux is not controlled with medical therapy alone.

People at a higher risk for esophageal cancer, such as those with Barrett’s esophagus, are often watched closely by their doctors to look for signs that the cells lining the esophagus have become more abnormal. If dysplasia (a pre-cancerous condition) is found, the doctor may recommend treatments to keep it from developing into esophageal cancer.

For those who have Barrett’s esophagus, daily treatment with a proton pump inhibitor might lower the risk of developing cell changes (dysplasia) that can turn into cancer. If you have chronic heartburn (or reflux), tell your doctor. Treatment can often improve symptoms and might prevent future problems.

Some studies have found that the risk of cancer of the esophagus is lower in people with Barrett’s esophagus who take aspirin or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen. However, taking these drugs every day can lead to problems, such as kidney damage and bleeding in the stomach. For this reason, most doctors don’t advise that people take NSAIDs to try to prevent cancer. If you are thinking of taking an NSAID regularly, discuss the potential benefits and risks with your doctor first.

Some studies have also found a lower risk of esophageal cancer in people with Barrett’s esophagus who take drugs called statins, which are used to treat high cholesterol. Examples include atorvastatin (Lipitor®) and rosuvastatin (Crestor®). While taking one of these drugs might help some patients lower esophageal cancer risk, doctors don’t advise taking them just to prevent cancer because they can have serious side effects.

What are the symptoms of esophageal cancer?

Early esophageal cancer typically causes no signs or symptoms. Cancers of the esophagus are usually found because of the symptoms they cause. Diagnosis in people without symptoms is rare and usually accidental (because of tests done for other medical problems). Unfortunately, most esophageal cancers do not cause symptoms until they have reached an advanced stage, when they are harder to treat.

The most common symptoms of esophageal cancer are:

- Backward movement of food through the esophagus and possibly mouth (regurgitation)

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia)

- Weight loss without trying

- Chest pain, pressure or burning

- Worsening indigestion or heartburn

- Coughing or hoarseness

- Chronic cough

- Vomiting

- Bone pain (if cancer has spread to the bone)

- Bleeding into the esophagus. This blood then passes through the digestive tract, which may turn the stool black. Over time, this blood loss can lead to anemia (low red blood cell levels), which can make a person feel tired.

Having one or more symptoms does not mean you have esophageal cancer. In fact, many of these symptoms are more likely to be caused by other conditions. Still, if you have any of these symptoms, especially trouble swallowing, it’s important to have them checked by a doctor so that the cause can be found and treated, if needed.

Patients commonly experience difficulty swallowing as the tumor gets larger and the width of the esophagus becomes narrowed. At first, most have trouble swallowing solid foods such as meats, breads or raw vegetables. As the tumor grows, the esophagus becomes more narrowed causing difficulty in swallowing even liquids. Cancer of the esophagus can also cause symptoms of indigestion, heartburn, vomiting and choking. Patients may also have coughing and hoarseness of the voice. Involuntary weight loss is also common.

How is esophageal cancer diagnosed?

Esophagus cancers are usually found because of signs or symptoms a person is having. If esophagus cancer is suspected, exams and tests will be needed to confirm the diagnosis. If cancer is found, further tests will be done to help determine the extent (stage) of the cancer.

Medical history and physical exam

If you have symptoms that might be caused by esophageal cancer, the doctor will ask about your medical history to check for possible risk factors and to learn more about your symptoms.

Your doctor will also examine you to look for possible signs of esophageal cancer and other health problems. He or she will probably pay special attention to your neck and chest areas.

If the results of the exam are abnormal, your doctor will probably order tests to help find the problem. You may also be referred to a gastroenterologist (a doctor specializing in digestive system diseases) for further tests and treatment.

Imaging tests to look for esophagus cancer

Imaging tests use x-rays, magnetic fields, sound waves, or radioactive substances to create pictures of the inside of your body. Imaging tests might be done for many reasons, such as:

- To help find a suspicious area that might be cancer

- To learn if and how far cancer has spread

- To help determine if the treatment is working

- To look for possible signs of cancer coming back after treatment

Barium swallow

In this test, a thick, chalky liquid called barium is swallowed to coat the walls of the esophagus. When x-rays are then taken, the barium clearly outlines the esophagus. This test can be done by itself, or as a part of a series of x-rays that includes the stomach and part of the intestine, called an upper gastrointestinal (GI) series. A barium swallow test can show any abnormal areas in the normally smooth surface of the inner lining of the esophagus, but it can’t be used to determine how far a cancer may have spread outside of the esophagus.

This is sometimes the first test done to see what is causing a problem with swallowing. Even small, early cancers can often be seen using this test. Early cancers can look like small round bumps or flat, raised areas (called plaques), while advanced cancers look like large irregular areas and can cause narrowing of the inside of the esophagus.

This test can also be used to diagnose one of the more serious complications of esophageal cancer called a tracheo-esophageal fistula. This occurs when the tumor destroys the tissue between the esophagus and the trachea (windpipe) and creates a hole connecting them. Anything that is swallowed can then pass from the esophagus into the windpipe and lungs. This can lead to frequent coughing, gagging, or even pneumonia. This problem can be helped with surgery or an endoscopy procedure.

Computed tomography (CT or CAT) scan

A CT scan uses x-rays to produce detailed cross-sectional images of your body. This test can help tell if esophageal cancer has spread to nearby organs and lymph nodes (bean-sized collections of immune cells to which cancers often spread first) or to distant parts of the body.

Before the test, you may be asked to drink 1 to 2 pints of a liquid called oral contrast. This helps outline the esophagus and intestines. If you are having any trouble swallowing, you need to tell your doctor before the scan.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

Like CT scans, MRI scans provide detailed images of soft tissues in the body. But MRI scans use radio waves and strong magnets instead of x-rays. A contrast material called gadolinium may be injected into a vein before the scan to see details better. MRI can be used to look at abnormal areas in the brain and spinal cord that might be due to cancer spread.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scan

PET scans usually use a form of radioactive sugar (known as fluorodeoxyglucose or FDG) that is injected into the blood. Normal cells use different amounts of the sugar, depending on how fast they are growing. Cancer cells, which grow quickly, are more likely to absorb larger amounts of the radioactive sugar than normal cells. These areas of radioactivity can be seen on a PET scan using a special camera.

The picture from a PET scan is not as detailed as a CT or MRI scan, but it provides helpful information about whether abnormal areas seen on these other tests are likely to be cancer or not.

If you have already been diagnosed with cancer, your doctor may use this test to see if the cancer has spread to lymph nodes or other parts of the body. A PET scan can also be useful if your doctor thinks the cancer may have spread but doesn’t know where.

PET/CT scan: Some machines can do both a PET and CT scan at the same time. This lets the doctor compare areas of higher radioactivity on the PET scan with the more detailed picture of that area on the CT scan.

Endoscopy

An endoscope is a flexible, narrow tube with a tiny video camera and light on the end that is used to look inside the body. Tests that use endoscopes can help diagnose esophageal cancer or determine the extent of its spread.

Upper endoscopy

This is an important test for diagnosing esophageal cancer. During an upper endoscopy, you are sedated (made sleepy) and then the doctor passes an endoscope down yourthroat and into the esophagus and stomach. The camera is connected to a monitor, which lets the doctor see any abnormal areas in the wall of the esophagus clearly.

The doctor can use special instruments through the scope to remove (biopsy) samples from any abnormal areas. These samples are sent to the lab to see if they contain cancer.

If the esophageal cancer is blocking the opening (called the lumen) of the esophagus, certain instruments can be used to help enlarge the opening to help food and liquid pass.

Upper endoscopy can give the doctor important information about the size and spread of the tumor, which can be used to help determine if the tumor can be removed with surgery.

Endoscopic ultrasound

This test is usually done at the same time as the upper endoscopy. For an endoscopic ultrasound, a probe that gives off sound waves is at the end of an endoscope. This allows the probe to get very close to tumors in the esophagus. This test is very useful in determining the size of an esophageal cancer and how far it has grown into nearby areas. It can also help show if nearby lymph nodes might be affected by the cancer. If enlarged lymph nodes are seen on the ultrasound, the doctor can pass a thin, hollow needle through the endoscope to get biopsy samples of them. This helps the doctor decide if the tumor can be removed with surgery.

Bronchoscopy

This exam may be done for cancer in the upper part of the esophagus to see if it has spread to the windpipe (trachea) or the tubes leading from the windpipe into the lungs (bronchi).

Thoracoscopy and laparoscopy

These exams let the doctor see lymph nodes and other organs near the esophagus inside the chest (by thoracoscopy) or the abdomen (by laparoscopy) through a hollow lighted tube.

These procedures are done in an operating room while you are under general anesthesia (in a deep sleep). A small incision (cut) is made in the side of the chest wall (for thoracoscopy) or the abdomen (for laparoscopy). Sometimes more than one cut is made. The doctor then inserts a thin, lighted tube with a small video camera on the end through the incision to view the space around the esophagus. The surgeon can pass thin tools into the space to remove lymph nodes and biopsy samples to see if the cancer has spread. This information is often important in deciding whether a person is likely to benefit from surgery.

Lab tests of biopsy samples

Usually if a suspected esophageal cancer is found on endoscopy or an imaging test, it is biopsied. In a biopsy, the doctor removes a small piece of tissue with a special instrument passed through the scope.

HER2 testing

If esophageal cancer is found but is too advanced for surgery, your biopsy samples may be tested for the HER2 gene or protein. Some people with esophageal cancer have too much of the HER2 protein on the surface of their cancer cells, which helps the cells grow. A drug that targets the HER2 protein called trastuzumab (Herceptin®) may help treat these cancers when used along with chemotherapy. Only cancers that have too much of the HER2 gene or protein are likely to be affected by this drug, which is why doctors may test tumor samples for it.

PD-L1 testing

An esophageal cancer that cannot be treated with surgery or has spread to distant sites may be tested to see if it makes a checkpoint protein called PD-L1. This protein is found in 35% to 45% of esophageal cancers. Tumors that make this protein might be treated with the immunotherapy drug pembrolizumab.

MMR and MSI testing

Esophageal cancer cells might be tested to see if they show high levels of gene changes called microsatellite instability (MSI), or if they have changes in any of the mismatch repair (MMR) genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, and PMS2).

Esophageal cancers that test positive for mismatch repair (MMR) or high microsatellite instability (MSI) and cannot be treated with surgery, have come back after initial treatment, or have spread to other parts of the body might benefit from immunotherapy with the drug pembrolizumab.

Blood tests

Your doctor might order certain blood tests to help determine if you have esophageal cancer.

Complete blood count (CBC): This test measures the different types of cells in your blood. It can show if you have anemia (too few red blood cells). Some people with esophageal cancer become anemic because the tumor has been bleeding.

Liver enzymes: You may also have a blood test to check your liver function, because esophageal cancer can spread to the liver.

What is the treatment for esophageal cancer?

Upper endoscopy (EGD) will be used to obtain a tissue sample from the esophagus to diagnose cancer. What treatments you receive for esophageal cancer are based on the type of cells involved in your cancer, your cancer’s stage, your overall health and your preferences for treatment.

If you’ve been diagnosed with esophageal cancer, your cancer care team will discuss your treatment options with you. It’s important that you think carefully about each of your choices. You will want to weigh the benefits of each treatment option against the possible risks and side effects.

There are several ways to treat esophageal cancer, depending on its type and stage.

Local treatments: Some treatments are called local therapies, meaning they treat the tumor in a specific location, without affecting the rest of the body. Types of local therapy used for esophageal cancer include:

- Surgery

- Radiation therapy

- Endoscopic treatments

These treatments are more likely to be useful for earlier stage (less advanced) cancers, although they might also be used in some other situations.

Systemic treatments: Esophageal cancer can also be treated using drugs, which can be given by mouth or directly into the bloodstream. These are called systemic therapies because they travel through your whole system, allowing them to reach cancer cells almost anywhere in the body. Depending on the type of esophageal cancer, several different types of drugs might be used, including:

- Chemotherapy

- Combined chemotherapy and radiation is called chemoradiotherapy or chemoradiation. You might have chemoradiotherapy before surgery. Or you might have it on its own as your main treatment.

- Targeted drug therapy

- Immunotherapy

Depending on the stage of the cancer and other factors, different types of treatment may be combined at the same time or used after one another.

Doctors are actively looking at new ways of combining various types of treatment to see if they may have a better effect on treating esophageal cancer. Many patients with esophageal cancer undergo some form of combination therapy with surgery, radiation and chemotherapy.

When the cancer is only in the esophagus and has not spread, surgery will be done. The cancer and part, or all, of the esophagus is removed. The surgery may be done using:

- Open surgery, during which one or two larger incisions are made.

- Minimally invasive surgery, during which a 2 to 4 small incisions are made in the belly. A laparoscope with a tiny camera is inserted into the belly through one of the incisions.

Radiation therapy may also be used instead of surgery in some cases when the cancer has not spread outside the esophagus.

Either chemotherapy, radiation, or both may be used to shrink the tumor and make surgery easier to perform.

If the person is too ill to have major surgery or the cancer has spread to other organs, chemotherapy or radiation may be used to help reduce symptoms. This is called palliative therapy. In such cases, the disease is usually not curable.

Beside a change in diet, other treatments that may be used to help the patient swallow include:

- Dilating (widening) the esophagus using an endoscope. Sometimes a stent is placed to keep the esophagus open.

- A feeding tube into the stomach.

- Photodynamic therapy, in which a special drug is injected into the tumor and is then exposed to light. The light activates the medicine that attacks the tumor.

Figure 9. Esophageal stent

References- Barrett esophagus. Medline Plus. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001143.htm

- Clermont M, Falk GW. Clinical Guidelines Update on the Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Esophagus. Dig Dis Sci. 2018 Aug;63(8):2122-2128. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5070-z

- Shaheen NJ, Falk GW, Iyer PG, Gerson LB; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG Clinical Guideline: Diagnosis and Management of Barrett’s Esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016 Jan;111(1):30-50; quiz 51. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.322. Epub 2015 Nov 3. Erratum in: Am J Gastroenterol. 2016 Jul;111(7):1077.

- Beg S, Ragunath K, Wyman A, Banks M, Trudgill N, Pritchard DM, Riley S, Anderson J, Griffiths H, Bhandari P, Kaye P, Veitch A. Quality standards in upper gastrointestinal endoscopy: a position statement of the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) and Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland (AUGIS). Gut. 2017 Nov;66(11):1886-1899. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314109. Epub 2017 Aug 18. Erratum in: Gut. 2017 Dec;66(12 ):2188.

- Japan Esophageal Society. Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer, 11th Edition: part I. Esophagus. 2017;14(1):1-36. doi: 10.1007/s10388-016-0551-7

- Akın H, Aydın Y. How should we describe, diagnose and observe the Barrett’s esophagus? Turk J Gastroenterol. 2017 Dec;28(Suppl 1):S26-S30. doi: 10.5152/tjg.2017.08

- Koike T, Saito M, Ohara Y, Hatta W, Masamune A. Current status of surveillance for Barrett’s esophagus in Japan and the West. DEN Open. 2022 Feb 13;2(1):e94. doi: 10.1002/deo2.94

- Fass R, Hell RW, Garewal HS, Martinez P, Pulliam G, Wendel C, Sampliner RE. Correlation of oesophageal acid exposure with Barrett’s oesophagus length. Gut. 2001 Mar;48(3):310-3. doi: 10.1136/gut.48.3.310

- Koek GH, Sifrim D, Lerut T, Janssens J, Tack J. Multivariate analysis of the association of acid and duodeno-gastro-oesophageal reflux exposure with the presence of oesophagitis, the severity of oesophagitis and Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2008 Aug;57(8):1056-64. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.119206

- Champion G, Richter JE, Vaezi MF, Singh S, Alexander R. Duodenogastroesophageal reflux: relationship to pH and importance in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1994 Sep;107(3):747-54. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90123-6

- Khieu M, Mukherjee S. Barrett Esophagus. [Updated 2022 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430979

- Barrett’s Esophagus. American College of Gastroenterology. https://gi.org/topics/barretts-esophagus/

- Desai TK, Krishnan K, Samala N, Singh J, Cluley J, Perla S, Howden CW. The incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in non-dysplastic Barrett’s oesophagus: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2012 Jul;61(7):970-6. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300730

- Erőss B, Farkas N, Vincze Á, Tinusz B, Szapáry L, Garami A, Balaskó M, Sarlós P, Czopf L, Alizadeh H, Rakonczay Z Jr, Habon T, Hegyi P. Helicobacter pylori infection reduces the risk of Barrett’s esophagus: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Helicobacter. 2018 Aug;23(4):e12504. doi: 10.1111/hel.12504

- Thrift AP. Barrett’s Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma: How Common Are They Really? Dig Dis Sci. 2018 Aug;63(8):1988-1996. doi: 10.1007/s10620-018-5068-6

- Michopoulos S. Critical appraisal of guidelines for screening and surveillance of Barrett’s esophagus. Ann Transl Med. 2018 Jul;6(13):259. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.05.09

- Bellizzi AM, Hafezi-Bakhtiari S, Westerhoff M, Marginean EC, Riddell RH. Gastrointestinal pathologists’ perspective on managing risk in the distal esophagus: convergence on a pragmatic approach. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018 Dec;1434(1):35-45. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13680

- Barrett Esophagus. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/171002-overview#showall

- Eating, Diet, & Nutrition for Barrett’s Esophagus. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disorders. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/digestive-diseases/barretts-esophagus/eating-diet-nutrition

- Cooper GS, Kou TD, Chak A. Receipt of previous diagnoses and endoscopy and outcome from esophageal adenocarcinoma: a population-based study with temporal trends. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 Jun;104(6):1356-62. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.159

- Cooper GS, Yuan Z, Chak A, Rimm AA. Association of prediagnosis endoscopy with stage and survival in adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia. Cancer. 2002 Jul 1;95(1):32-8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10646

- Prasad GA, Wang KK, Buttar NS, Wongkeesong LM, Krishnadath KK, Nichols FC 3rd, Lutzke LS, Borkenhagen LS. Long-term survival following endoscopic and surgical treatment of high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2007 Apr;132(4):1226-33. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.017