The pineal gland

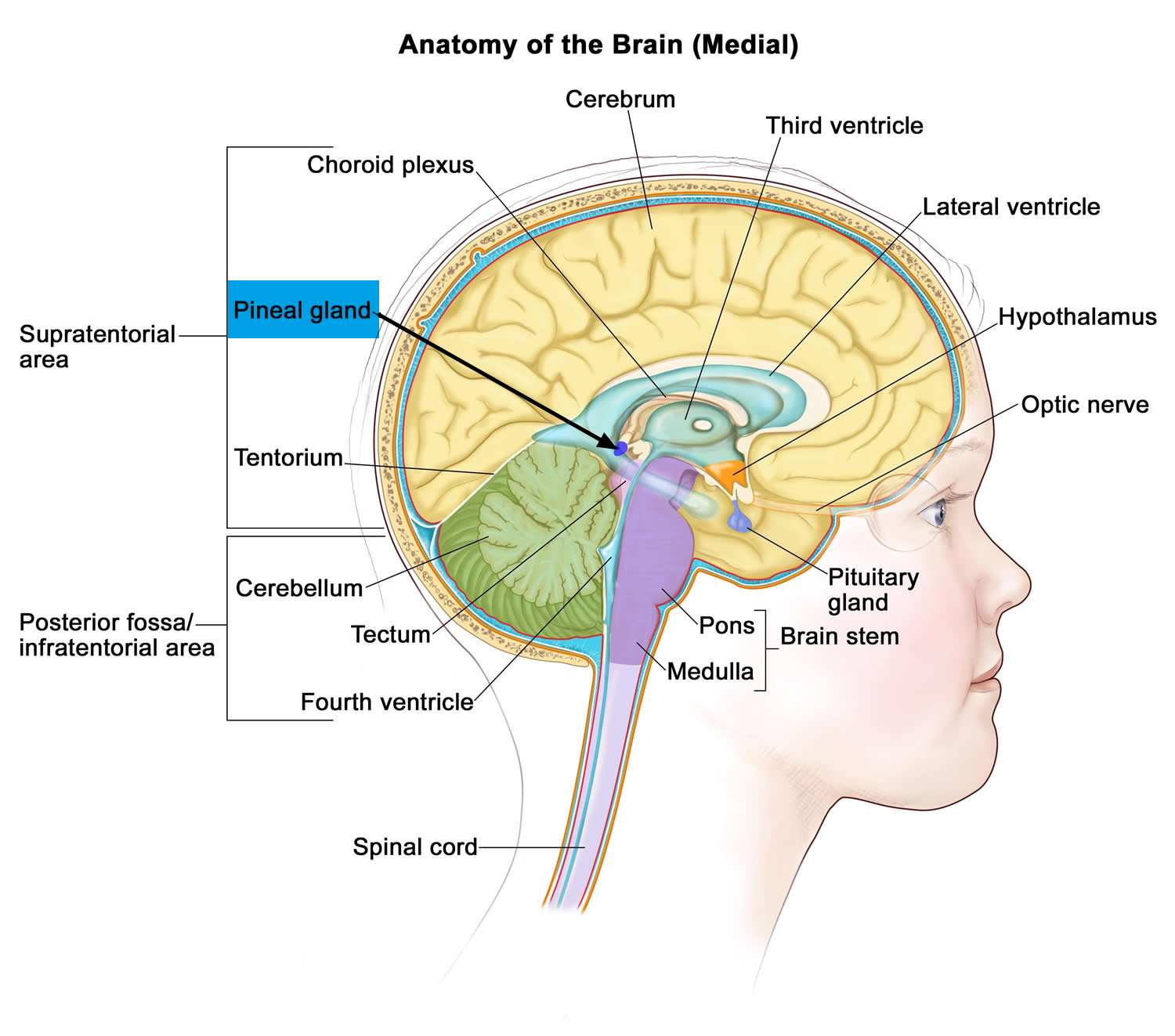

The pineal gland is a small pine cone like shape of highly vascularized structure weighing 100-150mg located deep between the cerebral hemispheres but outside the blood-brain barrier where it is attached to the upper part of the thalamus near the roof of the third ventricle by a short stalk (see Figures 1 and 2) 1. The normal pineal gland appears as a small reddish-brown structure and the normal size ranges between 10 and 14 mm 2. Two primary cell types make up the pineal gland. The pineocyte is the principal parenchyma cell and comprises 95% of the pineal gland. The other 5% are supporting cells referred to as astrocytes. Together, these two cell types are arranged in lobules, which are separated by a fibrovascular stroma. Calcifications commonly occur within the pineal gland and are often associated with increasing age 3, 4.

It was reported that several physiological or pathological conditions alter the morphology of the pineal glands 3. For example, the pineal gland of obese individuals is usually significantly smaller than that in a lean subject 5. The pineal gland volume is also significantly reduced in patients with primary insomnia compared to healthy controls and further studies are needed to clarify whether low pineal volume is the basis or a consequence of a functional sleep disorder 6. These observations indicate that the phenotype of the pineal gland may be changeable by health status or by environmental factors, even in humans 3. The largest pineal gland was recorded in newborn South Pole seals; it occupies one third of their entire brain 7. The pineal size decreases as they grow. Even in the adult seal, however, the pineal gland is considerably large and its weight can reach up to approximately 4000 mg, 27 times larger than that of a human. This huge pineal gland is attributed to the harsh survival environments these animals experience 8.

To the present day, the functions of the pineal gland are not fully understood 9. Current knowledge indicates that by secretion of melatonin (N-acetyl-5-hydroxytryptamine), the pineal gland plays an important role in the regulation of the sleep-wake cycle and of reproductive function (e.g. onset of puberty) 10, with melatonin also acting as a neuroprotector or antioxidant 11, 12.

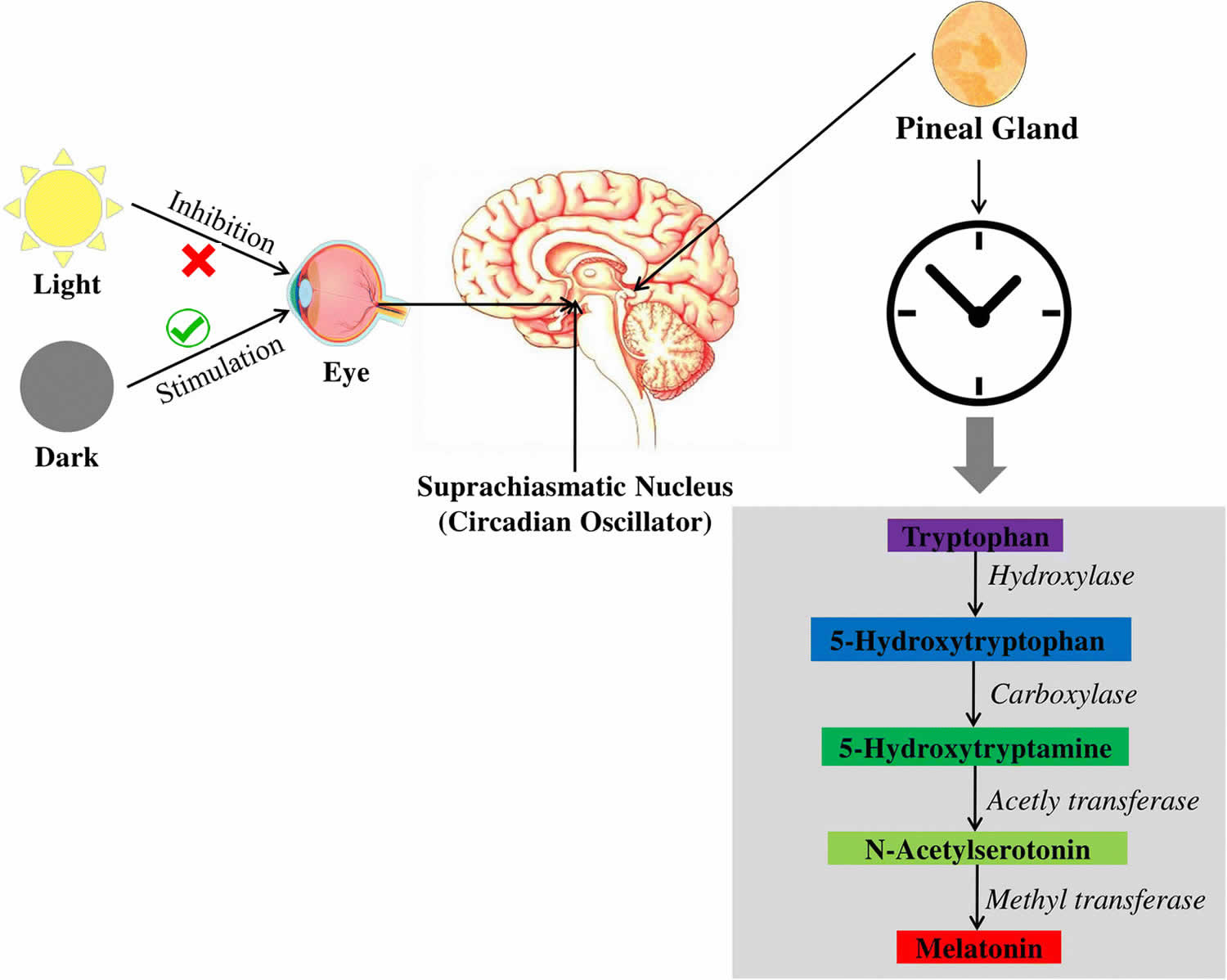

The pineal gland translates the rhythmic cycles of night and day encoded by the retina into hormonal signals that are transmitted to the rest of the neuronal system in the form of serotonin and melatonin synthesis and release 13. The pineal gland secretes the hormone melatonin in response to changing light conditions outside the body (see Figure 3 below). Impulses originating in the retinas of the eyes are conducted along a complex pathway that eventually reaches the pineal gland. Melatonin secretion is suppressed during the day and increases in the dark of night.

Melatonin may help to regulate circadian rhythms. Circadian rhythms are patterns of repeated activity associated with the environmental cycles of day and night, including the sleep–wake cycle. The fact that melatonin secretion responds to day length may explain why traveling across several time zones produces the temporary insomnia of jet lag.

Previous studies have suggested a decline of melatonin secretion with age and an association between melatonin decrease and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s disease 14, 15, 16, 17. The amount of uncalcified pineal tissue was shown to predict total melatonin excretion with lack of melatonin being hypothesized to result from pineal gland calcification 18, 19. As a consequence, detection and measurement of pineal gland calcification might be of clinical interest by identifying patients with possible melatonin deficits and a risk for the development of neurodegenerative diseases 18, 19.

In addition, the pineal gland also produces some peptides 20 and other methylated molecules, for example, N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT or N,N-DMT) 21, a potent psychedelic. This chemical was suggested to be exclusively generated by the pineal gland at birth, during dreaming, and/or near death to produce “out of body” experiences 22. However, the exact biological consequences (if any) of these substances remain to be clarified. Recently, it was reported that pineal gland is an important organ to synthesize neurosteroids from cholesterol. These neurosteroids include testosterone, 5α- and 5β-dihydrotestosterone (5α- and 5β-DHT), 7α-hydroxypregnenolone (7α-OH PREG) and estradiol-17β (E2). The machinery for synthesis of these steroids has been identified in the pineal gland. 7α-hydroxypregnenolone (7α-OH PREG) is the major neurosteroid synthesized by the pineal gland. Its synthesis and release from the pineal gland exhibits a circadian rhythm and it is regulates the locomote activities of some vertebrates, especially in birds 23. These observations opened a new avenue for functional research on pineal gland; the observations require further confirmation.

Figure 1. Pineal gland

Note: The pineal gland is commonly located along the midline above the superior colliculi and inferior to the splenium of the corpus callosum. It is attached to the superior aspect of the posterior border of the third ventricle.

Figure 2. Pineal gland

Biological rhythms

Biological rhythms are changes that systematically recur in organisms. The period of any rhythm is the duration of one complete cycle. The frequency of a rhythm is the number of cycles per time unit.

Three common types of rhythms in humans are:

- Ultradian rhythm: Ultradian rhythms have periods shorter than 24 hours and include the cardiac cycle and the breathing cycle,

- Infradian rhythm: Periods of infradian rhythms, such as the female reproductive cycle, are longer than 24 hours,

- Circadian rhythm: Periods of circadian rhythms, such as the sleep–wake cycle, variation in body temperature, and changes in hormone secretion, are approximately 24 hours.

Both external (exogenous) and internal (endogenous) factors regulate human biological rhythms. Exogenous factors are environmental components, such as daily temperature changes and the light–dark cycle. Endogenous factors include “clock” genes. Many members of an extended family in Utah, for example, have “advanced sleep phase syndrome” due to a mutation in a gene called “period.” The effect is striking—they promptly fall asleep at 7:30 each night and awaken suddenly at 4:30 a.m 24.

The sleep–wake cycle is the most obvious circadian rhythm in humans. It is largely controlled by the pattern of daylight and night, but under laboratory conditions of constant light or dark, the human body eventually follows an approximately 25-hour cycle.

Using a backlit electronic device, such as a smartphone or tablet, can delay falling asleep long after the device is shut off. Experiments show that such light exposure decreases melatonin production by about 22 percent. Body temperature is mostly endogenously regulated, but light exposure and physical activity help

keep this rhythm on a 24- rather than 25-hour cycle. Body temperature is usually lowest between 4 and 6 a.m., and then increases and peaks between 5 and 11 p.m. It drops during the late evening hours and into the night.

Platelet cohesion, blood pressure, and pulse rate are typically highest 2 hours after awakening. This may explain why heart attacks and strokes are more likely to occur between 6 a.m. and noon than at other times. Plasma cortisol surges and peaks at about 6 a.m., and then gradually declines to its minimum level in late evening before increasing again in the early morning. Growth hormone secretion peaks during the night. Antidiuretic hormone secretion is greater at night, when it decreases urine formation.

Pineal gland function

The main function of the pineal gland is to receive and convey information about the current light-dark cycle from the environment and, consequently produce and secrete melatonin cyclically at night (dark period) 1. Melatonin is the main hormone secreted by the pineal gland. Extrapineal sources of melatonin were reported in the retina, bone marrow cells, platelets, skin, lymphocytes, Harderian gland, cerebellum, and especially in the gastrointestinal tract of vertebrate species 25. Indeed, melatonin is present but can also be synthesized in the enterochromaffin cells; the release of gastrointestinal melatonin into the circulation seems to follow the periodicity of food intake, particularly tryptophan intake 26. It is noteworthy that the concentration of melatonin in the gastrointestinal tract surpasses blood levels by 10-100 times and there is at least 400 times more melatonin in the gastrointestinal tract than in the pineal gland 26. Melatonin in the gastrointestinal tract of newborn and infant mammals is of maternal origin given that melatonin penetrates easily the placenta and is after secreted into the mother’s milk 27. It has even been suggested that melatonin is involved in the production of mekonium 26. Melatonin in human breast milk follows a circadian rhythm in both preterm and term milk, with high levels during the night and undetectable levels during the day 28. No correlation was found between gestational age and concentration of melatonin. It is noteworthy that bottle milk composition does not contain melatonin in powder formula. Also, human colostrum, during the first 4 or 5 days after birth, contains immune – competent cells (colostral mononuclear cells) which are able to synthesize melatonin in an autocrine manner 29.

Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-hydroxytryptamine) is mainly synthesized by the pinealocytes from the amino acid tryptophan, which is hydroxylated (by the tryptophan-5-hydroxylase) into 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), then decarboxylated (by the 5-hydroxytryptophan decarboxylase) into serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT) (see Figure 5). Two enzymes, found mainly in the pineal gland, transform serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5-HT) to melatonin (N-acetyl-5-hydroxytryptamine) 30: serotonin is first acetylated to form N-acetylserotonin by arylalkylamine-N-acetyltransferase (AA-NAT, also called “Timezyme”, is the rate-limiting enzyme for melatonin synthesis), and then N-acetylserotonin is methylated by acetylserotonin-O-methyltransferase (ASMT, also called hydroxyindole-O- methyltransferase or HIOMT) to form melatonin (Figure 2). Both AA-NAT and ASMT activities are controlled by noradrenergic and neuropeptidergic projections to the pineal gland 31. Norepinephrine, also called noradrenaline, activates adenylate cyclase which in turn promotes the melatonin biosynthesis enzymes, especially AA-NAT 32. Once synthesized, melatonin is quickly released into the systemic circulation to reach central and peripheral target tissues.

Melatonin synthesis and secretion is enhanced by darkness and inhibited by light (Figure 3) 33. Luminous information is transmitted from the retina to pineal gland through the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus. In humans, its secretion starts soon after sundown, reaches a peak in the middle of the night (between 2 and 4 in the morning) and decreases gradually during the second half of the night 34. Nearly 80% of the melatonin is synthesized at night, with serum concentrations varying between 80 and 120 pg/ml. During daylight hours, serum concentrations are low (10-20 pg/ml) 35.

Serum concentrations of melatonin vary considerably with age, and infants secrete very low levels of melatonin before 3 months of age. Melatonin secretion increases and becomes circadian along with child development: Sadeh 36 reported an association between melatonin secretion and organization of sleep-wake rhythm from 6 months of age. However, more recent studies suggest that melatonin rhythm is set around 3 months of age in typical development, at the same time that infants begin to have more regular sleep–wake cycles associated with nighttime sleep lasting 6-8 h 37. In 3-years-old children, a stabilization of the sleep-wake rhythm is observed, which corresponds to a regular melatonin secretion rhythm. Nocturnal concentration peaks are the highest between the 4th and 7th years of age 38 and then decline progressively 39.

Both serotonin-N-acetyltransferase (NAT) and serotonin availability play a role limiting melatonin production 1. Serotonin-N-acetyltransferase (NAT) mRNA is expressed mainly in the pineal gland, retina, and to a lesser extent in some other brain areas, pituitary, and testis. Serotonin-N-acetyltransferase (NAT) activation is trigger by the activation of β1 and α1b adrenergic receptors by norepinephrine 40. Norepinephrine is the major transmitter via β-1 adrenoceptors with potentiation by α-1 stimulation. Norepinephrine levels are higher at night, approximately 180 degrees out of phase with the serotonin rhythm. Both availability of norepinephrine and serotonin are stimulatory for melatonin synthesis. Pathological or traumatic sympathetic denervation of the pineal gland or administration of β-adrenergic antagonists abolishes the rhythmic synthesis of melatonin and the light-dark control of its production.

Recently, it has been found that almost all organs, tissues and cells tested have the ability to synthesize melatonin using the same pathway and enzymes the pineal uses 41. These include, but not limited to, skin, lens, ciliary body, retina, gastrointestinal tract, testis, ovary, uterus, bone marrow, placenta, oocytes, red blood cells, platelets, lymphocytes, astrocytes, glia cells, mast cells and neurons 3, acting in an autocrine or paracrine manner 42. In the autocrine signaling process, molecules act on the same cells that produce them. In paracrine signaling, they act on nearby cells. Autocrine signals include extracellular matrix molecules and various factors that stimulate cell growth. Nevertheless, except for the pineal gland, these structures contribute little to circulating concentrations in mammals, since after pinealectomy, melatonin levels remain undetectable 43. It was calculated that the amounts of extrapineal derived melatonin is much greater than that produced by the pineal 44. However, the extra pineal-derived melatonin cannot replace/compensate for the role played by the pineal-derived melatonin in terms of circadian rhythm regulation. As scientists know pineal melatonin exhibits a circadian rhythm in circulation and in the CSF with a secretory peak at night and low level during the day 45; thus, the primary function of the pineal-derived melatonin is as a chemical signal of darkness for vertebrates 46. This melatonin signal helps the animals to cope with the light/dark circadian changes to synchronize their daily physiological activities (feeding, metabolism, reproduction, sleep, etc.).

Several other factors, summarized in Table 1, have been related to the secretion and production of melatonin 47.

After intravenous or oral administration, melatonin is quickly metabolized, mainly in the liver and secondarily in the kidney. However, after intravenous administration, the hepatic bio-degradation is less important due to the absence of hepatic first pass. It undergoes hydroxylation to 6-hydroxymelatonin by the action of the cytochrome P450 enzyme CYP1A2, followed by conjugation with sulfuric acid (90%) or glucuronic acid (10%) and is excreted in the urine. About 5% of serum melatonin is excreted unmetabolized also in urine. The principal metabolite, the 6-sulfatoxy-melatonin, is inactive, and its urinary excretion reflects melatonin plasma concentrations 48. Plasma levels can be also measured directly or indirectly assessed through salivary measures. A reverse relation between bioavailability of melatonin and the 6-sulfatoxy-melatonin concentrations area under the curve has been shown, the low bioavailability being explained by an important hepatic first pass 49.

Table 1. Factors influencing human melatonin secretion and production

| Factor | Effect(s) on melatonin | Comment |

| Light | Suppression | >30 lux white 460-480 nm most effective |

| Light | Phase-shift/ Synchronization | Short wavelengths most effective |

| Sleep timing | Phase-shift | Partly secondary to light exposure |

| Posture | ↑ standing (night) | |

| Exercise | ↑ phase shifts | Hard exercise |

| ß-adrenoceptor-antagonist | ↓ synthesis | Anti-hypertensives |

| Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine or 5HT) uptake inhibitor | ↑ fluvoxamine | Metabolic effect |

| Norepinephrine uptake inhibitor | ↑ change in timing | Antidepressants |

| MAOA inhibitor | ↑ may change phase | Antidepressants |

| α-adrenoceptor-antagonist | ↓ alpha-1, ↑ alpha-2 | |

| Benzodiazepines | Variable↓ diazepam, alprazolam | GABA mechanisms |

| Testosterone | ↓ | Treatment |

| Oral contraceptives | ↑ | |

| Estradiol | ↓? Not clear | |

| Menstrual cycle | Inconsistent | ↑ amenorrhea |

| Smoking | Possible changes ↑↓ ? | |

| Alcohol | ↓ | Dose dependent |

| Caffeine | ↑ | Delays clearance (exogenous) |

| Aspirin, Ibuprofen | ↓ | |

| Chlorpromazine | ↑ | Metabolic effect |

| Benserazide | Possible phase change, Parkinson patients | Aromatic amino-acid decarboxylase-inhibitor |

Abbreviations: A: antagonist, U: uptake, I: inhibitor, MAO: monoamine oxidase, OC: oral contraceptives, 5HT: 5-hydroxytryptamine.

[Source 1 ]Figure 3. Melatonin plasma concentrations – Circadian profile (in grey is represented the period of darkness)

Footnote: Melatonin (N-acetyl-5-hydroxytryptamine) is synthesized within the pinealocytes from tryptophan, mostly occurring during the dark phase of the day. The duration of melatonin secretion each day is directly proportional to the length of the night. The mechanism behind this pattern of melatonin secretion during the night (dark cycle) is that activity of the rate-limiting enzyme in melatonin synthesis – serotonin N-acetyltransferase (NAT) – responsible for the transformation of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5HT, serotonin) to N-acetylserotonin (NAS), is low during daylight and peaks during the dark phase. Finally, N-acetylserotonin is converted to melatonin by acetylserotonin O-methyltransferase.

Figure 4. Melatonin chemical structure

Figure 5. Melatonin synthesis

Footnote: AA-NAT = arylalkylamine-N-acetyl-transferase; ASMT = acetylserotonin-O-methyltransferase

[Source 50 ]Footnote: In higher vertebrates, light is sensed by the inner retina (retinal ganglion cells) that send neural signals to the visual areas of the brain. However, a few retinal ganglion cells contain melanopsin and have intrinsic photoreceptor capability that send neural signals to non-image forming areas of the brain, including the pineal gland through complex neuronal connections. The photic information from the retina is sent to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), the major rhythm-generating system or “clock” in mammals, and from there to the hypothalamus. When the light signal is positive, the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) secretes gamma-amino butyric acid (GABA), responsible for the inhibition of the neurons that synapse in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus, consequently the signal to the pineal gland is interrupted and melatonin is not synthesized. On the contrary, when there is no light (darkness), the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) secretes glutamate, responsible for the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) transmission of the signal along the pathway to the pineal gland. The paraventricular nucleus (PVN) communicates with higher thoracic segments of spinal column, conveying information to the superior cervical ganglion that transmits the final signal to the pineal gland through sympathetic postsynaptic fibers by releasing norepinephrine (NE). Norepinephrine (noradrenaline) is the trigger for the pinealocytes to produce melatonin by activating the transcription of the mRNA encoding the enzyme serotonin-N-acetyltransferase (arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase, AA-NAT), the first molecular step for melatonin synthesis 51.

Control of melatonin synthesis

The rhythm of melatonin production is internally generated and controlled by interacting networks of “clock genes” in the bilateral suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) 52. Damage to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) leads to a loss of the majority of circadian rhythms. The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) rhythm is synchronized to 24 hours mainly by the light-dark cycle acting via the retina and the retinohypothalamic projection to the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN); the longer the night the longer the duration of secretion is, and the ocular light serves to synchronize the rhythm to 24 hour and to suppress secretion at the end of the dark phase, as explained above. Light exposure is the most important factor related to pineal gland function and melatonin secretion. A single daily light pulse of suitable intensity and duration in otherwise constant darkness is enough to phase shift and to synchronize the melatonin rhythm to 24 hour 53. The amount of light required at night to suppress melatonin secretion varies across species. In humans, intensities of 2500 lux full spectrum light (domestic light is around 100 to 500 lux) or light preferably in the blue range (460 to 480 nm) are required to completely suppress melatonin at night and shift the rhythm, but lower intensities < 200 lux might suppress secretion 54. Furthermore, the degree of light perception between individuals is related with the incidence of circadian desynchrony; along these lines, blind people with unconscious light perception show abnormally synchronized melatonin and other circadian rhythms 55. Some blind subjects retain an intact retinohypothalamic tract and therefore a normal melatonin response despite a lack of conscious light perception 56. It seems clear that an intact innervated pineal gland is necessary for the perfection of photoperiod change 57. Melatonin functions as a paracrine signal within the retina, it enhances retinal function in low intensity light by inducing photomechanical changes and provides a closed-loop to the pineal-retina-suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) system. All together, they are the basic structures to perceive and transduce non-visual effects of light, and to generate the melatonin rhythm by a closed-loop negative feedback (Clock, “Circadian locomotor output cycles kaput” and Bmal, “Brain and muscle ARNT-like” genes), positive stimulatory elements (Per, “period” and Cry, “Cryptochrome” genes), and negative elements (CCG, clock-controlled genes) of clock gene expression in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN).

Low melatonin level is considered as a biomarker of aging 58. As to the association between the aging and melatonin production, in most vertebrates, melatonin production wanes with aging. The reasons for this may be two-fold. Melatonin synthetic capacity is dampened during aging due to the reduced density of β-adrenergic receptors in the pineal gland 59 and the downregulation of gene expression or phosphorylation of arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase (AANAT) or serotonin-N-acetyltransferase (NAT) 60. A second reason is the increased consumption of melatonin. This is due to the metabolic alterations. For example, more reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated by the aged cells than in the young cells and melatonin as the endogenous antioxidant is used to neutralize the overproduced ROS in aging organisms. Both of these effects may cause its low levels in the aged vertebrates. When melatonin production was depressed by pinealectomy in rats, accumulation of oxidatively-damaged products accelerated their aging process 61. In contrast, when young pineal glands were grafted to the old animals or exogenous melatonin was supplemented, both significantly increased the life span of experimental animals 62.

Physiological effects of melatonin

Melatonin regulates circadian rhythms such as the sleep-wake rhythm, neuroendocrine rhythms or body temperature cycles through its action on melatonin receptors (MT-1 and MT-2) 63. Ingestion of melatonin induces fatigue, sleepiness and a diminution of sleep latency 64. Disturbed circadian rhythms are associated with sleep disorders and impaired health 65. For example, children with multiple developmental, neuro-psychiatric and health difficulties often show melatonin deficiency 66. When circadian rhythms are restored, behavior, mood, development, intellectual function, health, and even seizure control may improve 65. It should be noted that according to several studies, circadian rhythms are important for typical (normal) neurodevelopment and their absence suppresses neurogenesis in animal models 67.

Finally, melatonin may be involved in early fetal development, with direct effects on placenta, glial and neuronal development, and could play an ontogenic role in the establishment of diurnal rhythms and synchronization of the fetal biological clock 68. Iwasaki et al. 68 investigated the expression of the two enzymes involved in the conversion of serotonin to melatonin (AA-NAT and ASMT) (see Figure 3 above) and found that transcripts of these enzymes were present in the first-trimester human placenta. Moreover, they found also that melatonin significantly potentiated hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) secretion at optimal concentrations on cultured human trophoblast cells. These results suggest that melatonin regulates in a paracrine/autocrine way human placental function with a potential role in human reproduction. Test tube studies have shown that neural stem/progenitor cells express melatonin MT1 receptors and melatonin induces glial cell-line derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) expression in neural stem cells, suggesting an early role for melatonin in central nervous system development. Indeed, as indicated previously, melatonin of maternal origin crosses the placenta and can therefore influence fetal development. Studies in humans have repeatedly confirmed that the cycle of melatonin in maternal blood occurs also in fetal circulation 69. The maturation and synchronization of the fetal circadian system have not been thoroughly studied. However, studies in nonhuman primate fetus have shown that maternal melatonin stimulates growth of the primate fetal adrenal gland and entrains fetal circadian rhythms, including suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) rhythms 70. Furthermore, in mice, the suppression of melatonin rhythm by maternal exposure to constant light changes the rhythmic expression in fetal clock genes; these changes are reversed when melatonin is injected daily to the mother 71. These results document that the fetal clock is imprinted by melatonin, which under normal circumstances is of maternal origin. In addition, some studies in humans and nonhuman primates show 24h rhythms in fetal heart rate and respiratory movements during the latter half of pregnancy. Whether the circadian system of the human fetus, particularly in late pregnancy, is under the influence of maternal suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) remains to be better ascertained 72.

Besides the well-known effects of melatonin on the regulation of sleep-wake rhythms, melatonin is considered as an endogenous synchronizer and a chronobiotic molecule, i.e. a substance that reinforces oscillations or adjusts the timing of the central biological clock located in the suprachiasmatic nuclei of the hypothalamus to stabilize bodily rhythms 73. Furthermore, Pevet and Challet 74 view melatonin as both the master clock output and internal time-giver in the complex circadian clocks network: as a major hormonal output, melatonin distributes, through its daily rhythm of secretion, temporal cues to the numerous tissue targets with melatonin receptors, driving circadian rhythms in some tissue structures such as the adenohypophysis or synchronizing peripheral oscillators such as the fetal adrenal gland but also many other peripheral tissues (pancreas, liver, kidney, heart, lung, fat, gut, etc.). Circadian rhythms, and more precisely the circadian clocks network, allow temporal organization of biological functions in relation to periodic environmental changes and therefore reflect adaptation to the environment. Thus, the sleep–wake rhythm associated with biological circadian rhythms can be seen as an adaptation to the day–night cycle. Moreover, the synchronization by melatonin of peripheral oscillators reflects adaptation of the individual to his/her internal and external environment (for example, the synchronized effects of melatonin on cortisol and insulin secretion allow the individual to be fully awake at 8am and able to start the day by eating and getting some energy from food intake). Given the major synchronizing effects of melatonin on central and peripheral oscillators, measures of melatonin are considered the best peripheral indices of human circadian timing 75.

Futhermore, melatonin is involved in blood pressure and autonomic cardiovascular regulation, immune system regulation but also various physiological functions such as retinal functions, detoxification of free radicals and antioxidant actions through its action on melatonin MT3 receptors protecting the brain from oxidative stress 76. A through its action on MT3 receptors specific section is developed below on melatonin and brain protection. The antioxidant actions of melatonin protect also the gastrointestinal tract from ulcerations by reducing secretion of hydrochloric acid and the oxidative effects of bile acids on the intestinal epithelium, and by increasing duodenal mucosal secretion of bicarbonate through its action on MT2 receptors (this alkaline secretion is an important mechanism for duodenal protection against gastric acid); melatonin prevents also ulcerations of gastrointestinal tract by increasing microcirculation and fostering epithelial regeneration 77. Concerning the role of melatonin in immune regulation, melatonin has direct immuno-enhancement effects in animals and humans 78. Indeed, melatonin stimulates the production of cytokines and more specifically interleukins (IL-2, IL-6, IL-12) 79. In addition, melatonin enhances T helper immune responses 80. Furthermore, the melatonin antioxidant actions contribute to its immuno-enhancing effects 79 and have also an indirect effect by reducing nitric oxide formation which facilitates the decrease of the inflammatory response 81. As suggested by Esquifino et al. 82, melatonin might provide a time-related signal to the immune network.

In addition, effects of melatonin on body mass and bone mass regulation have been reported. Melatonin is known for its role in energy expenditure and body mass regulation in mammals by preventing the increase in body fat with age 83. These effects are mediated by MT2 receptors in adipose tissue 84. Moreover, melatonin increases bone mass by promoting osteoblast cell differentiation and bone formation 85. In humans, melatonin stimulates bone cell proliferation and Type I collagen synthesis in these cells, and inhibits bone resorption through down-regulation of the RANKL-mediated osteoclast formation and activation 86. Also, a deficit of melatonin has been found to be associated with animal scoliosis following pinealectomy and human idiopathic scoliosis 87.

Finally, melatonin has physiological effects on reproduction and sexual maturation in mammals through down-regulation of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) gene expression in a cyclical pattern over a 24-hour period 88. The rhythmic release of GnRH controls luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicule-stimulating hormone (FSH) secretion. The daily profile of melatonin secretion conveys internal information used for both circadian and seasonal temporal organization 74. The melatonin rhythmic pattern entrains the reproductive rhythm via the influence of photoperiod on LH pulsatile secretion and therefore mediates the seasonal fluctuations of reproduction clearly observed in animals (seasonal breading as species-specific seasons for reproduction) and moderately observed in humans 89.

Pineal gland calcification

Pineal gland calcification also known as “brain sand”, “psammoma bodies”, pineal concretions, corpora arenacea or acervuli, is calcium deposition (hydroxyapatite deposits [Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2]) in pineal gland and was observed as early as in 1653 in humans 90 and is very common with a reported prevalence of approximately 68–75% in adults 91, 92, 93. Apart from humans, pineal calcification was also identified in a wide range of species including ox, sheep, horse, donkey, monkey, cow, gerbil, rat, guinea pig, chicken and turkey 94. Thus, pineal calcium metabolism and pineal calcification are wide spread phenomenon across species. In all population groups, calcification of the pineal gland was found to increase with age 91, 93 and in some species the pineal calcification rates are as high as 100% with age 95, 96. Ironically, pineal calcification also occurs in neonatal humans 97, 98. Studies have shown that pineal gland calcification can be noted in children as young as 5 years 99. The degree and frequency of pineal calcification have been noted to increase with age 100. Pineal gland calcification also depends on environmental factors, such as altitude and sunlight exposure 100. And it has been hypothesized that increased pineal gland calcification results in decreased melatonin production 101. Pineal gland calcification reduces CSF melatonin levels and dampens its rhythm resulting in chronological disturbance including insomnia and migraine. The low levels of CSF melatonin also elevate neuronal damage from reactive oxygen species (ROS), thus, accelerating the neurodegenerative disorders 3.

Pineal calcification occurs when calcareous deposits form within the connective tissue of the pineal gland stroma 102. Unlike kidney stones, the main component of pineal calcification is hydroxyapatite [Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2] and the Calcium/Phosphorus molar ratio in pineal calcification is similar to that found in the enamel and dentine of teeth 103. Pineal gland calcification is frequently detected on computed tomography (CT) scans 9. As CT causes substantial radiation exposure, it would be of advantage to identify pineal gland calcification with MRI instead. Apart from the absence of ionizing radiation, MRI provides superior soft-tissue contrast and is the modality of choice to evaluate the pineal region, as it enables an accurate delineation of pineal tumors before surgery. However, in the case of calcifications of the pineal gland or tumor calcifications in the pineal region, conventional MRI sequences do not allow for a reliable identification and have a poor sensitivity, as calcifications appear hypointense on T1, T2 and T2*weighted sequences and consequently cannot be reliably differentiated from e.g. soft tissue artifacts or microbleeds 9.

Some researchers believe that pineal calcification was associated with certain neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis), schizophrenia 104, bipolar disorder 105, migraine, symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage, symptomatic cerebral infarction 106, sleep disorders 107, defective sense of direction, pediatric primary brain tumor 108 and breast cancer 109, 110, 111, 112, 113, 114. Others feel that it is a natural process and has no consequences for human physiopathology since this process occurs early in childhood 115 and it also may not impact the melatonin synthetic ability of the pineal gland in some animals 116, 117. Recently, additional studies have shown that reduced pineal gland volume and pineal calcification jeopardizes the melatonin production in humans due to the decreased function in the pineal gland tissue 118 and resulting in altered sleep patterns 107.

A few studies reported that pineal calcification trigger severe sleep disorders by disturbing melatonin secretion in the pineal gland 119, 118 and pineal cysts 120. In clinical studies, patients with primary insomnia showed reduced plasma melatonin levels during the daytime 121.

Decades ago several studies pointed out the relationship between the pineal calcification and schizophrenia 122, 123. The highest pineal calcium content was detected in the pineal gland of patients who died of kidney disease associated with hypertension among other diseases 124. Currently, additional studies have reported the strong association of pineal gland calcification and neurodegenerative diseases, particularly Alzheimer’s disease 101 accompanied by cognitive decline and sleep disturbances 125 and aging 100.

This association is connected with the melatonin levels synthesized by this gland. It is well established that melatonin is a neuroprotector with its potent antioxidant function and anti-inflammatory activity 126, 127, 128. The brain is rich in lipid, lacks the antioxidative enzyme, catalase, and consumes large quantity of oxygen (roughly 20% of the total oxygen consumed by the brain with 1% of the total body weight). This makes the brain more vulnerable to the oxidative stress than other organs. Decrease of endogenous melatonin will result in the neurons being less resistance to the oxidative stress or brain inflammation. The mechanistic investigations uncovered that in addition to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities, melatonin directly inhibits the secretion and deposition of the β amyloid protein (Alzheimer’s disease plague) 129, 130 which is the hallmark of this disease; it also suppresses tau protein hyperphosphorylation thereby reducing intracellular neurotangles 131, 132, another biomarker of Alzheimer’s disease.

In Alzheimer’s disease, reduced pineal size, pineal gland dysfunction, and pineal calcification have been reported 133 and decreased melatonin levels have been detected in serum 134 and urine 135 of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Previous researches demonstrated that the reduction of melatonin levels in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and serum leads to the aggravation of Alzheimer’s disease neuropathology 136, 133, 137. A recent computed tomography study clearly observed pineal calcification in Alzheimer’s disease patients 101. However, the detailed mechanisms on pineal gland calcification and pineal gland dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease are not fully understood yet 125. The majority of the small scale clinical trials support that melatonin application improved the symptoms of sundowning syndrome and retarded the progress of Alzheimer’s disease 138, 139.

The most suggestive results come from the animal studies. In single, double or triple gene mutated Alzheimer’s disease animal models large doses of melatonin (100 mg/L drinking water or 10 mg/kg body weight/day) prolonged their life span, positively modulated the biochemical and morphological alterations and improved their cognitive performance 140, 141, 142. To date, the large doses of melatonin used in animal studies have not been applied in human clinical trials of Alzheimer’s disease or for dementia prevention, though several trials have examined its short-term effects on cognitive function. Clinical trials in humans have reported mixed effects of melatonin on short-term cognitive functions. In one trial, melatonin improved verbal memory, with slight improvements in other cognitive tests 143. Another trial showed that a single dose of melatonin enhanced memory functions while under stress, but not after stress 144. However, in a third trial, melatonin cream 12.5% did not result in significant effects on cognition 145. Other clinical trials have found that melatonin treatment significantly lowered the risk of delirium, which is a risk factor for dementia 146, 147. But a trial of 452 patients found that treatment with melatonin after surgery did not reduce the incidence of delirium 148.

Clinical trials have not shown that melatonin can slow disease progression or improve cognitive function in patients with dementia or mild cognitive impairment. A recent meta-analysis of patients with Alzheimer’s and other dementias concluded that there are no significant benefits of melatonin on cognitive scores or measures of sleep 149. In 2015, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline 150 recommended against the use of melatonin and sleep-promoting medications for elderly people with dementia due to increased risks of falls and other adverse events.

No clinical studies have tested whether melatonin effects are different in APOE4 carriers. One preclinical study tentatively reported that melatonin could protect from possible toxicity from APOE4 151 but the findings have not yet been replicated.

What causes pineal gland calcification?

The exact cause, formation processes and mechanisms of pineal gland calcification is currently unknown. Here, we summarize several opinions, hypothesis and speculations on the potential mechanisms of pineal gland calcification formation. Large amounts of evidence suggests that the pineal gland calcification was associated with human pathological disorders and aging. A great deal of attention has recently been given to the relationship of decreased melatonin levels in neurodegenerative diseases and aging associated pineal calcification. With the increased use of the PET scan, susceptibility-weighted magnetic resonance imaging or other advanced technologies, even very small pineal concretions can be identified in patients or animals, which could not be seen previously. It was found that the rates of pineal calcification have been significantly underestimated previously. For example, in non-specifically targeted patients with the average age of 58.7 ± 17.4 years, 214 out of 346 showed gland calcification on CT scans (62%) 152; the data of 12,000 healthy subjects from Turkey indicated that the highest intracranial calcifications occurred in the pineal gland with an incidence of 71.6% 153. Pineal gland calcification appears to occur without significant differences among countries, regions and races. For example, in Iran the gland calcification incidence is around 71% 154 and in African (Ethiopia), it is roughly 72% 155 and in black people in the US it is 70% 156.

Some studies found that pineal gland calcification was restricted to the connective tissue. The mechanisms involved the formation of calcareous deposits within the connective tissue stroma of the gland 157. These deposits represent the aging-related calcium accumulation within the connective tissue. This type of calcification is similar to that found in the habenular commissure and choroid plexus 158. The connective tissue derived pineal gland calcification is predominant in the rat 159 and Pirbright white guinea pig 160. In analysis of the specimens of human pineal gland, Maslinska et al. 97 reported that the initiation of pineal gland calcification was associated with the tryptase-containing mast cells. During the systemic or local pathological conditions, the tryptase-containing mast cells infiltrate into the pineal gland where they release biologically active substances including tryptase which participates in calcification. This process is pathological but not age related since it also occurs in the children.

The high accumulation of fluoride in pineal gland hydroxyapatite (among those chronically exposed) points to a plausible mechanism by which fluoride may influence sleep patterns 161. In adults, pineal gland fluoride concentrations have been shown to strongly correlate with degree of pineal gland calcification 162, 163. Interestingly, greater degree of pineal calcification among older adolescents and/or adults is associated with decreased melatonin production 164, lower REM sleep percentage, decreased total sleep time, poorer sleep efficiency 165, greater sleep disturbances and greater daytime tiredness 166. While there are no existing human studies on fluoride exposure and melatonin production or sleep behaviors, findings from a doctoral dissertation demonstrated that gerbils fed a high fluoride diet had lower nighttime melatonin production than those fed a low fluoride diet 167. Moreover, their melatonin production was lower than normal for their developmental stage 168. Therefore, it is possible that excess fluoride exposure may contribute to increased pineal gland calcification and subsequent decreases in nighttime melatonin production that contribute to sleep disturbances 167. Additional animal and prospective human studies are needed to explore this hypothesis.

As to the pineal gland calcification of pinealocyte-origin, two speculations should be mentioned. One is proposed by Lukaszyk and Reiter 169. They reported that the pinealocytes extruded polypeptides into the extracellular space in conjunction with their hypothetic carrier protein, neuroepiphysin. The pineal polypeptides of exocytotic microvesicles were actively exchanged for the calcium. The calcium-carrier complex then is formed and deposited on the surface of adjacent mutilayed concretions. Thus, the concretion formation is related to the secretory function of pineal gland. For example, in the gerbil following the superior cervical ganglionectomy, the pineal gland calcification are completely inhibited; this was attributed to a decrease in the functional activity of the gland 170. However, this cannot explain the observation of intracellular calcification of the pinealocytes 171. Krstić 172 proposed another mechanism to explain the origin of pineal gland calcification from pinealocytes. He speculated that the cytoplasmic matrix, vacuoles, mitochondria and the endoplasmic reticulum of large clear pinealocytes were the initial intracellular calcification sites. These loci, and particularly those within the cytoplasmic matrix, transformed into acervuli by a further addition of hydroxyapatite crystals. The cells gradually degenerated, died, broke down, and the acervuli reached the extracellular space. High intracellular calcium levels could be a situation that is responsible for eliminating calcium from the cell, with the hypercalcemic intracellular milieu promoting the initial crystallization. The failure of Ca2+-ATPase could be a natural process of aging or pathological conditions 173. Hence, pineal gland calcification does not occur under normal conditions and it is a result of altered molecular processes in vertebrates. These speculations; however, cannot completely explain the mechanisms of the pineal gland calcification formation. In another speculation, which is a complementary of the previous suggestions, it seems that the pineal gland calcification in some cases is an active rather than a passive process. Tan et al 174 previously hypothesized that the pineal gland may have a blood filtration function like the kidney since its vascular structures as well as its blood flow rate are similar to the kidney. The question is whether they share a similarity to the calcification this is observed in both organs. It is well documented that the compositions of pineal gland calcification is totally different from the kidney stone 3. Kidney stones are primarily composed of calcium oxalate and its formation is simply a sedimentary process caused by high concentrations of both calcium and oxalate 175. A main component of a pineal gland calcification is hydroxyapatite [Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2] 103 which is the chief structural element of vertebrate bone. The Ca/P molar ratio in pineal concretions is similar to the enamel and dentine 176 and these authors pointed out that the nature and crystallinity of the inorganic tissue of the pineal concretions lead one to think of a physiological rather than pathological ossification type with characteristics between enamel and dentine. It is not very clear how the hydroxyapatite is formed in the bone but there is little doubt that its formation involves the collaboration of bone cells and it is a programmed process. In addition, the concentric laminated pineal concretions are frequent observed 177 to be structurally similar the osteons, the major unit of compact bone.

The laminated pineal stone indicates its formation is not random but organized and programmed 3. For example, in humans, laminated pineal stones are associated with aging. The older the individual, the larger number of lamellae 177. Tan et al 3 hypothesis is that the pineal calcification, at least partially, may be similar to the bone formation that is, the pineal calcium deposit may be formed by differentiated bone cells under certain conditions. Recently, numerous studies have reported that melatonin facilitates the capacity of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) to differentiate into osteoblast-like cells under in vivo or in vitro conditions 178. Mesenchymal cells are found in the early stage of pineal development in birds and in rats 179. Mesenchymal cells have an important role in pineal follicular formation later during development of the pineal gland. It was also documented that the striated muscle fibers are present in the pig 180 and rat pineal gland 181. These striated muscle fibers are of mesenchymal rather than ectodermal origin 181. These observations indicate that the mesenchymal stem cells are present in the pineal gland and they have the capacity to differentiate into different cell types including muscle as well as probably the osteoblasts and even the osteocytes. The mesenchymal stem cells in the pineal gland may be retained from its early embryonic stage of mesenchymal tissue and/or they may be of vasculature origin. The differentiation from mesenchymal stem cells into osteoblasts/osteocytes seems to be melatonin dependent. The signal transduction pathway of this transition is probably mediated by melatonin membrane receptor 2 (MT2) 181. The detailed mechanism was proposed by Maria and Witt-Enderby 182. Simply, melatonin binds to the MT2 of mesenchymal stem cells to promote them to differentiate into pre-osteoblasts. At the same time melatonin increases the levels of parathyroid hormone (PTH); type I collagen and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and these factors further promote pre-osteoblasts to form osteoblasts. Finally, melatonin upregulates the gene expression of the osteopontin (OSP), bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2), osteocalcin (OCN) and ALP and facilitates the osteoblast proliferation, osteocyte formation, mineralization and bone formation.

Transgenic knockout of the membrane receptor 2 (MT2) in mice inhibited the osteoblast proliferation and bone formation 183. This indicates that the pineal gland has the capacity to form the bone like structure (calcification) by the pathway including mesenchymal stem cells. The promotor is the high levels of melatonin generated by this gland. The process of pineal gland calcification in bird (turkey) resembles the bone formation which strongly supports our hypothesis. It requires a microenvironment which includes collagen fibrils, phosphate and calcium. The osteocyte-like cells are found in the center of the pineal concretion and the peripheral part contains the osteoblast-like cells and densely packed collagen fibrils 184. The intermediate portion is the place of mineralization as bone.

Pineal Gland Cyst

Pineal gland cysts are common. Pineal cysts are relatively common and may be found by chance in up to 10% of people who have a head CT scan or MRI 185. Most people with a pineal cyst do not have any signs or symptoms 186. Rarely, a pineal cyst may cause headaches, hydrocephalus, obstruction of the vein of Galen (a vein at the base of the brain), Parinaud syndrome (also known as dorsal midbrain syndrome, which leads to difficulty of upward vertical gaze, mydriasis, blepharospasm and impaired ocular convergence), or other symptoms 187, 188. The exact cause of pineal cysts is unknown. Treatment is usually only considered when a cyst causes symptoms. In most cases, no treatment is necessary for a pineal gland cyst 189. Treatment may involve open or stereotactic (a surgical technique for precisely directing the tip of a delicate instrument (e.g a needle) or beam of radiation in three planes using coordinates provided by medical imaging) removal of the cyst, stereotactic aspiration, and/or CSF diversion (a procedure used to drain fluid from the brain) 188.

A cyst is a sac that can form in any part of the body. Often cysts are filled with air, fluid or other material. Cysts that occur in the pineal gland almost never cause symptoms. So, it is unlikely that headaches are the result of a pineal gland cyst. In most cases, these cysts are discovered when a brain scan is done for an unrelated reason, such as a head trauma, migraine headaches or dizzy spells. Pineal gland cysts are most commonly found in women 20 to 30 years old, and are very rare before puberty or after menopause. This suggests hormones may play a role in causing the cysts.

Because they do not usually cause symptoms or lead to complications, the vast majority of pineal gland cysts do not require surgery or other treatment. Pineal cysts are best seen on brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This type of brain imaging is typically reviewed by a specialist, such as a neuroradiologist, who is experienced in evaluating brain cysts and tumors. That physician can tell the difference between a simple pineal gland cyst and another condition that may require treatment, such as a pineal gland tumor.

In contrast to cysts, tumors are an abnormal mass of tissue. They can be either noncancerous or cancerous. If a pineal gland tumor is found, treatment depends on the specific type, size and location of the tumor, as well as the individual’s overall health and preferences. In many cases, surgery is often the first step in treating pineal gland tumors.

Pineoblastoma

Pineoblastoma is a rare, aggressive type of cancer that begins in the cells of the brain’s pineal gland 190. Your pineal gland, located in the center of your brain, produces a hormone (melatonin) that plays a role in your natural sleep-wake cycle.

Pineoblastoma can occur at any age, but it tends to occur most often in young children 190. Pineoblastoma may cause headaches, sleepiness and subtle changes in the way the eyes move 190.

Pineoblastoma can be very difficult to treat. It can spread within the brain and the fluid (cerebrospinal fluid) around the brain, but it rarely spreads beyond the central nervous system. Treatment usually involves surgery to remove as much of the cancer as possible. Additional treatments may also be recommended.

Diagnosis of pineoblastoma

Tests and procedures used to diagnose pineoblastoma include:

- Imaging tests. Imaging tests can help your doctor determine the location and size of your child’s brain tumor. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is often used to diagnose brain tumors, and advanced techniques, such as perfusion MRI and magnetic resonance spectroscopy, may also be used.

Additional tests might include computerized tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography (PET).

- Removing a sample of tissue for testing (biopsy). A biopsy can be done with a needle before surgery or during surgery to remove the pineoblastoma. The sample of suspicious tissue is analyzed in a laboratory to determine the types of cells and their level of aggressiveness.

- Removing cerebrospinal fluid for testing (lumbar puncture). Also called a spinal tap, this procedure involves inserting a needle between two bones in the lower spine to draw out cerebrospinal fluid from around the spinal cord. The fluid is tested to look for tumor cells or other abnormalities. In certain situations, cerebrospinal fluid may instead be collected during a biopsy procedure to remove suspicious tissue from the brain.

Treatment for pineoblastoma

Pineoblastoma treatment options include:

- Surgery to relieve fluid buildup in the brain. A pineoblastoma may grow to block the flow of cerebrospinal fluid, which can cause a buildup of fluid that puts pressure on the brain (hydrocephalus). An operation to create a way for the fluid to flow out of the brain may be recommended. Sometimes this procedure can be combined with a biopsy or surgery to remove the tumor.

- Surgery to remove the pineoblastoma. The brain surgeon (neurosurgeon) will work to remove the pineoblastoma with the goal of removing as much of the tumor as possible. But it’s often impossible to remove the tumor entirely because pineoblastoma forms near critical structures deep within the brain. Most children with pineoblastoma receive additional treatments after surgery to target the remaining cells.

- Radiation therapy. Radiation therapy uses high-energy beams, such as X-rays or protons, to kill cancer cells. During radiation therapy, your child lies on a table while a machine moves around him or her, directing beams to the brain and spinal cord, with additional radiation to the tumor. Because there is a high risk the tumor cells can spread beyond the initial site to other areas of the central nervous system, radiation therapy directed to the entire brain and spinal cord is recommended for children older than 3.

- Chemotherapy. Chemotherapy uses drugs to kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy may be recommended after surgery or radiation therapy in children with pineoblastoma. In some cases, it’s used at the same time as radiation therapy. For larger tumors, chemotherapy may be used before surgery to shrink the tumor and make it easier to remove.

- Radiosurgery. Technically a type of radiation and not an operation, stereotactic radiosurgery focuses multiple beams of radiation on precise points to kill the tumor cells. Radiosurgery is sometimes used to treat pineoblastoma that recurs.

- Clinical trials. Clinical trials are studies of new treatments. These studies give you a chance to try the latest treatment options, but the risk of side effects may not be known. Ask your doctor whether your child might be eligible to participate in a clinical trial.

Melatonin supplement

Melatonin is a hormone secreted by the pineal gland in the brain. It helps regulate other hormones and maintains the body’s circadian rhythm. The circadian rhythm is an internal 24-hour “clock” that plays a critical role in when you fall asleep and when you wake up. When it is dark, your body produces more melatonin. When it is light, the production of melatonin drops. Being exposed to bright lights in the evening, or too little light during the day, can disrupt the body’s normal melatonin cycles. For example, jet lag, shift work, and poor vision can disrupt melatonin cycles.

Some scientific evidence supports use of melatonin to minimize the effects of jet lag, especially in people traveling eastward over 2 to 5 time zones 191, 192. However, in one well-designed study, melatonin supplements did not relieve symptoms of jet lag 193 and only a few small studies suggest that these supplements can relieve jet lag symptoms 194, 195, indicating that clinical trial results are inconsistent.

Standard dosage is not established and ranges from 0.5 to 5 mg orally taken 1 hour before usual bedtime on the day of travel and 2 to 4 nights after arrival. Evidence supporting use of melatonin as a sleep aid in adults and children with neuropsychiatric disorders (eg, pervasive developmental disorders) is less strong.

Melatonin also helps control the timing and release of female reproductive hormones 196. It helps determine when a woman starts to menstruate, the frequency and duration of menstrual cycles, and when a woman stops menstruating (menopause). Preliminary research suggests low levels of melatonin help identify women at risk of a pregnancy complication called pre-eclampsia 196.

Some researchers also believe that melatonin levels may be related to aging 196. For example, young children have the highest levels of nighttime melatonin. Researchers believe these levels drop as we age. Some people think lower levels of melatonin may explain why some older adults have sleep problems and tend to go to bed and wake up earlier than when they were younger. However, newer research calls this theory into question.

Melatonin has strong antioxidant effects. Preliminary evidence suggests that it may help strengthen the immune system 196.

Melatonin levels may also play a role in 196, 197:

- regulating the immune response or immune system function

- regulating development and aging

- temperature homeostasis

- the development of cardiovascular diseases, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and osteoporosis

- mood

However, it is not confirmed whether melatonin levels cause, or are a consequence of, specific conditions because they may strongly influence sleep 197. The most common use of melatonin as a supplement is to aid in sleep 198.

There is very limited information in the literature about the influence of a pineal cyst on melatonin secretion. A recent study concluded that their patients with a pineal cyst retained a pattern of melatonin secretion comparable to those without a pineal cyst. However, this study had several limitations, including a small sample size of 4 patients. It should be noted that those who have a pineal cyst removed will no longer produce melatonin. Possible consequences of melatonin deficiency other than expected sleep disturbances are difficult to identify 197.

If you are considering using melatonin supplements, talk to your doctor first.

How much melatonin should I take?

The typical adult dose ranges from 0.3 mg to 5 mg at bedtime. Lower doses often work as well as higher doses. Intake of an usual dose (i.e., 1 to 5 mg), allows within the hour after ingestion, melatonin concentrations 10 to 100 times higher than the physiological nocturnal peak to be obtained, with a return to basal concentrations in 4 to 8 hours 50. A bioavailability study in four male healthy volunteers 199 showed a plasma melatonin peak varying between 2 and 395 nmol/L and an elimination half-life of 47± 3 min (mean ± SD) after oral administration of a 0.5 mg dose. Bioavailability varied from 10 to 56% (mean 33%).

Read the directions on the label of the pill bottle. These will tell you how much melatonin to take and how often to take it. If you have questions about how to take melatonin, call your doctor or pharmacist. Do not take more than the recommended amount. Taking more melatonin does not make it work quicker or better. Overdosing on any medicine can be dangerous.

Keep a record of all medicines and supplements you take and when you take them. Take this list with you when you go to the doctor. Ask your doctor if it’s okay to take melatonin if:

- You take other prescription or over the counter (OTC) medicines.

- You have ongoing health problems.

- You are pregnant or nursing (it is unclear what effect melatonin can have on an unborn baby or nursing infant).

Melatonin for sleep

How to Take Melatonin for Sleep (Insomnia):

Dosage: Take melatonin 0.1 mg to 0.5 mg thirty minutes before bedtime. The most effective dose and length of treatment vary by individual. Treatment can range from a few days (for jet lag) to nine months (for trouble falling asleep) and should be overseen by a physician. Studies suggest melatonin for sleep may be effective in promoting but not maintaining sleep (early morning awakening).

How to Take Melatonin for Shift-Work Sleep Disorders

Dosage: Take melatonin 1.8 mg to 3 mg thirty minutes prior to the desired onset of daytime sleep; melatonin may NOT lead to improved alertness during the nighttime work shift and may only improve daytime sleep time by about 30 minutes.

How to Take Melatonin for Delayed Sleep Phase Disorder

Delayed sleep phase disorder most often occurs in adolescents, possibly due to reduced melatonin production and melatonin deficiency at this age. Sleep onset is delayed by 3 to 6 hours compared with conventional bedtimes (10 to 11 pm). Delayed sleep phase disorder can negatively affect school performance, daily activities, and lead to morning drowsiness which can be dangerous for teen drivers. Any sleep disorder in an adolescent should be evaluated by a physician.

Dosage: Take melatonin 1 mg four to six hours before set bedtime. Once a set bedtime is achieved, use maintenance doses of 0.5 mg melatonin 2 hours before expected sleep onset. Bright light therapy and behavioral management may enhance results. Be aware drowsiness may occur after melatonin dose, so avoid hazardous activities such as driving.

How to Take Melatonin for Non-24-Hour Sleep Wake Disorder (Non-24)

More than 70% of people who are totally blind have Non-24, a circadian rhythm disorder. For people who are totally blind, there are no light cues to help reset the biological clock. The sleep time and wake up time of people who have Non-24-Hour Sleep Wake Disorder shifts a little later every day. Sleep times go in and out of alignment compared to a normal sleep-wake phase. Extra minutes add up each day by day and disrupt the normal wake-sleep pattern.

Use of melatonin in Non-24 is to aid in stimulation to reset the biological clock with one long sleep time at night and one long awake time during the day. However, no large-scale clinical trials of melatonin therapy for Non-24 have been conducted to date.

Dosage: Studies on the blind suggest that 0.5 mg/day melatonin is an effective dose.

Hetlioz, a prescription-only melatonin agonist is also approved for use in Non-24-Hour Sleep Wake Disorder in blind individuals.

Hetlioz (tasimelteon)

Fast-dissolving Melatonin

Some melatonin tablets are available in fast-dissolving formulations in the U.S. To take the orally disintegrating tablet:

- Use dry hands to remove the tablet and place it in your mouth.

- Do not swallow the tablet whole. Allow it to dissolve in your mouth without chewing. If desired, you may drink liquid to help swallow the dissolved tablet.

Call your doctor if the condition you are treating with melatonin does not improve, or if it gets worse while using this product.

Store at room temperature away from moisture and heat.

Melatonin for children

Parents may consider using melatonin to help their child who has a trouble falling asleep. Only use melatonin for your child under the care of a pediatrician or other medical sleep specialist. Insomnia or other sleeping disorders in children should always be evaluated by a medical professional. Children 6 months to 14 years of age with sleep disorders : Melatonin 2 to 5 mg has been used.

Melatonin should not be used as a substitute for good sleep hygiene and consistent bedtime routines in children.

Products containing lower-dose melatonin for kids do exist on the U.S. market. However, long-term use of melatonin has not been studied in children and possible side effects with prolonged use are not known. Use for children with autism spectrum disorder or attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder should involve behavioral interventions and should be directed by a physician.

Delayed sleep phase disorder often occurs in teenagers and young adults, possibly due to alterations in endogenous melatonin production. Sleep onset is delayed by 3 to 6 hours compared with normal bedtime hours of 10 to 11 PM. Maintaining a consistent bedtime free of electronics for at least one hour prior to bedtime is especially important for children and adolescents.

Melatonin Side Effects in Children

The most common melatonin side effect in children is morning drowsiness. Other common side effects in children include:

- Bedwetting

- Headache

- Dizziness

- Nausea

- Diarrhea

- Possible increased risk for seizures in children with severe neurological disorders.

Dietary melatonin supplements can still have drug interactions or health risks if you have certain medical conditions, upcoming surgery, or other health concerns.

Melatonin benefits

Melatonin supplements may help some people with certain sleep disorders, including jet lag, sleep problems related to shift work, and delayed sleep phase disorder (one in which people go to bed but can’t fall asleep until hours later), and insomnia. Unlike many other sleep medications, with melatonin you are unlikely to become dependent, have a diminished response after repeated use (habituation), or experience a hangover effect.

If melatonin for sleep isn’t helping after a week or two, stop using it. And if your sleep problems continue, talk with your health care provider.

If melatonin does seem to help, it’s safe for most people to take nightly for one to two months. After that, stop and see how your sleep is. Be sure you’re also relaxing before bed, keeping the lights low and sleeping in a cool, dark, comfortable bedroom for optimal results.

Sleep Disorders

Studies suggest that melatonin may help with certain sleep disorders, such as jet lag, delayed sleep phase disorder (a disruption of the body’s biological clock in which a person’s sleep-wake timing cycle is delayed by 3 to 6 hours), sleep problems related to shift work, and some sleep disorders in children. It’s also been shown to be helpful for a circadian rhythm sleep disorders in the blind that causes changes in blind peoples’ sleep and wake times. Melatonin can help improve these disorders in adults and children.

However, study results are mixed on whether melatonin is effective for insomnia in adults, but some studies suggest it may slightly reduce the time it takes to fall asleep.

Jet lag

Jet lag is caused by rapid travel across several time zones; its symptoms include disturbed sleep, daytime fatigue, indigestion, and a general feeling of discomfort. To ease jet lag, try taking melatonin two hours before your bedtime at your destination, starting a few days before your trip.

- In a 2009 research review, results from six small studies and two large studies suggested that melatonin may ease jet lag symptoms, such as alertness.

- In a 2007 clinical practice guideline, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine supported using melatonin to reduce jet lag symptoms and improve sleep after traveling across more than one time zone.

You can also adjust your sleep-wake schedule to be in sync with your new time zone by simply staying awake when you reach your destination—delaying sleep until your usual bedtime in the new time zone. Also, get outside for natural light exposure.

Melatonin for Jet Lag:

- Eastbound: If you are traveling east, say from the US to Europe, take melatonin after dark, 30 minutes before bedtime in the new time zone or if you are on the plane. Then take it for the next 4 nights in the new time zone, after dark, 30 minutes before bedtime. If drowsy the day after melatonin use, try a lower dose.

- Westbound: If you are heading west, for example, from the US to Australia, a dose is not needed for your first travel night, but you then may take it for the next 4 nights in the new time zone, after dark, 30 minutes before bedtime. Melatonin may not always be needed for westbound travel.

Given enough time (usually 3 to 5 days), jet lag will usually resolve on its own, but this is not always optimal when traveling.

Delayed Sleep Phase Disorder

In this disorder your sleep pattern is delayed two hours or more from a conventional sleep pattern, causing you to go to sleep later and wake up later. Adults and teens with delayed sleep-wake phase sleep disorder have trouble falling asleep before 2 a.m. and have trouble waking up in the morning. Research shows that melatonin reduces the length of time needed to fall asleep and advances the start of sleep in young adults and children with this condition. Talk to your child’s doctor before giving melatonin to a child.

- In a 2007 review of the literature, researchers suggested that a combination of melatonin supplements, a behavioral approach to delay sleep and wake times until the desired sleep time is achieved, and reduced evening light may even out sleep cycles in people with this sleep disorder.

- In a 2007 clinical practice guideline, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommended timed melatonin supplementation for this sleep disorder.

Shift Work Disorder

Shift work refers to job-related duties conducted outside of morning to evening working hours. About 2 million Americans who work afternoon to nighttime or nighttime to early morning hours are affected by shift work disorder.

- A 2007 clinical practice guideline and 2010 review of the evidence concluded that melatonin may improve daytime sleep quality and duration, but not nighttime alertness, in people whose jobs require them to work outside the traditional morning to evening schedule.

- The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommended taking melatonin prior to daytime sleep for night shift workers with shift work disorder to enhance daytime sleep.

Insomnia

Insomnia is a general term for a group of problems characterized by an inability to fall asleep and stay asleep. Research suggests that melatonin might provide relief from the inability to fall asleep and stay asleep (insomnia) by slightly improving your total sleep time, sleep quality and how long it takes you to fall asleep.

- In adults. A 2013 analysis of 19 studies of people with primary sleep disorders found that melatonin slightly improved time to fall asleep, total sleep time, and overall sleep quality. In a 2007 study of people with insomnia, aged 55 years or older, researchers found that prolonged-release melatonin significantly improved quality of sleep and morning alertness.

- In children. There’s limited evidence from rigorous studies of melatonin for sleep disorders among young people. A 2011 literature review suggested a benefit with minimal side effects in healthy children as well as youth with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, autism, and several other populations. There’s insufficient information to make conclusions about the safety and effectiveness of long-term melatonin use.

Sleep-wake cycle disturbances in children

Sleep problems are one of the most common problems parents encounter with their children. There are some simple steps parents can take to improve their children’s sleep, such as having a set bedtime and bedtime routine, avoiding foods or drinks with caffeine, and limiting the amount of screen time. Melatonin can help treat these sleep-wake cycle disturbances in children with a number of disabilities. For example, children with multiple developmental, neuro-psychiatric and health difficulties often show melatonin deficiency 66. When circadian rhythms are restored, behavior, mood, development, intellectual function, health, and even seizure control may improve 65.

Other therapeutic effects of melatonin

Therapeutic effects of melatonin have been reported in several disorders such as certain tumors, cardiovascular diseases or psychiatric disorders. The part concerning melatonin and psychiatric disorders is in particular developed given our past and current work on this topic.

Indeed, oncostatic effects of melatonin have been reported in several tumors (breast cancer, ovarian and endometrial carcinoma, human uveal melanoma, prostate cancer, hepatomas, and intestinal tumors) 200. These oncostatic effects have been attributed to the anti-oxidative role of melatonin given that oxidative stress is involved in the initiation, promotion and progression of carcinogenesis 201. Also, decreased melatonin levels (measures of blood melatonin or urinary excretion of 6-SM) were reported in patients with cardiovascular diseases 202. Inversely, melatonin treatment reduces blood pressure in patients with hypertension 203.

Concerning psychiatric disorders, secretion disturbances of the pineal gland have been described in child and adult psychiatry, with notably in most studies a decreased nocturnal melatonin secretion observed in major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or autism spectrum disorder 204.

Also, a phase-shift of melatonin has been reported in major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder, including in particular a delayed melatonin peak secretion 205. It is noteworthy that increased melatonin levels (measures of blood melatonin and urinary excretion of 6-SM) were found when clinical therapeutic benefits were observed following the use of antidepressants 206. Furthermore, significant improvement of major depressive disorder and anxiety was described following administration of 25mg per day of agomelatine, a MT1/MT2 melatonin agonist and selective antagonist of 5-HT2C receptors 207.

Autism spectrum disorder

Concerning autism spectrum disorder (ASD), abnormalities in the serotoninergic system and sleep-wake rhythm disturbances observed in children with autism spectrum disorder suggest altered melatonin secretion in autism 208. Sleep disorders (mostly increased sleep latency, reduced total sleep and nocturnal awakenings with insomnia) are observed in 50-80% of individuals with autism 209. It is noteworthy that sleep problems are not specific of autism and are also observed in children with intellectual disability associated or not with autism 210. However, melatonin measures in children with intellectual disability not associated with autism, such as some children with Down syndrome and Fragile X syndrome, showed respectively normal melatonin production despite delayed nocturnal melatonin peak secretion and increased levels of melatonin 211, whereas decreased nocturnal melatonin secretion was mostly observed in children with autism 210. Scientists reported in two different large samples of children with autism significant relationships between decreased nocturnal urinary excretion and severity of autistic impairments in social communication 212, 213. These results suggest that abnormalities in melatonin physiology might contribute not only to sleep problems in autism, but also to biological and psychopathological mechanisms involved in the development of autism spectrum disorder (for example, certain immunological abnormalities found in autism, such as a decrease number of T lymphocytes, might be explained by the hypo-functioning of the melatonin system).

Schizophrenia

Concerning schizophrenia, as suggested by Morera-Fumero and Abreu-Gonzalez 204, a possible explanation for the “low melatonin syndrome” present in some individuals with schizophrenia may stem from the study of the melatonin-synthesizing enzymes, the AA-NAT and ASMT. Furthermore, according to some authors, MT3 might be involved in the melatonin disturbances observed in schiozophrenia 214. Finally, melatonin secretion was also studied in obsessive compulsive disorder but no abnormalities in melatonin levels were reported.

Brain Protection