What is Wilms tumor

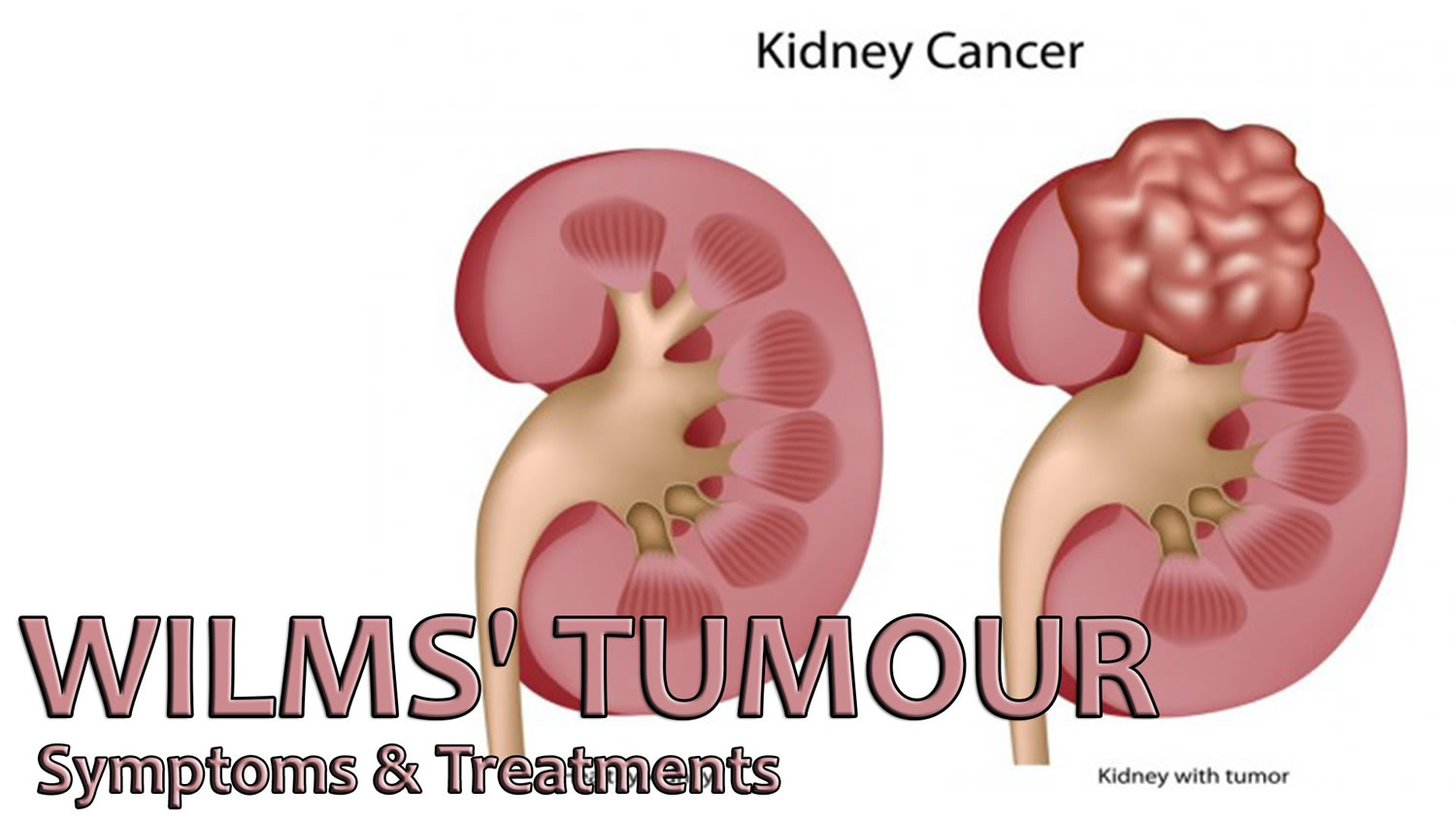

Wilms tumor also known as nephroblastoma, is the most common type of kidney cancer in children 1, 2, 3. In children and adolescents younger than 15 years old, most kidney cancers are Wilms tumors. About 9 of 10 kidney cancers in children are Wilms tumors, but Wilms tumor can happen in adults too (Wilms tumor is very rare in adults). Wilms tumor develops from cells called nephroblasts and so are also called nephroblastoma 4. Dr Max Wilms wrote the first medical paper about this condition. This is how it got its name.

Wilms tumor can affect one kidney (unilateral) or both kidneys (bilateral). Most Wilms tumors are unilateral, which means they affect only one kidney. Most often there is only one tumor, but 5% to 10% of children with Wilms tumors have more than one tumor in the same kidney. About 5% of children with Wilms tumors have tumors in both kidneys (bilateral disease). About 10% of children with Wilms tumor have an associated congenital malformation syndrome (see Table 1 below) 5. Of 295 consecutive patients with Wilms tumor seen at the Institut Curie in Paris, 52 (17.6%) had anomalies or syndromes, 43 of which were considered major, and 14 of which were genetically proven tumor predisposition syndromes 6. Children with Wilms tumor may have associated hemihyperplasia and urinary tract anomalies, including cryptorchidism (undescended testicle) and hypospadias (a birth defect in boys in which the opening of the urethra is not located at the tip of the penis) 1. Children may have recognizable phenotypic syndromes such as overgrowth, aniridia, genetic malformations, and others. These syndromes have provided clues to the genetic basis of Wilms tumor. The phenotypic syndromes and other conditions have been grouped into overgrowth and non-overgrowth categories (Table 1). Overgrowth syndromes and conditions are the result of excessive prenatal and postnatal somatic growth 7, 8.

Wilms tumors often become quite large before they are noticed. The average newly found Wilms tumor is many times larger than the kidney in which it started. Most Wilms tumors are found before they have spread (metastasized) to other organs. Wilms tumor may spread to the lungs, liver, bone, brain, or nearby lymph nodes.

Symptoms include a lump in the abdomen, blood in the urine, and a fever for no reason. Tests that examine the kidney and blood are used to find the tumor.

Even if a doctor thinks a child might have a cancer such as Wilms tumor based on a physical exam or imaging tests, they can’t be sure until a small piece of the tumor is checked in a lab.

Doctors usually diagnose and remove Wilms tumor in surgery. Other treatments include chemotherapy and radiation and biologic therapies. Biologic therapy boosts your body’s own ability to fight cancer.

Having certain genetic conditions or birth defects can increase the risk of getting Wilms tumor. Children that are at risk should be screened for Wilms tumor every three months until they turn eight.

Each year, about 500 to 650 new cases of Wilms tumors are diagnosed in the United States 2, 9, 10. This number has been fairly stable for many years. About 5% of all cancers in children are Wilms tumors.

Wilms tumors tend to occur in young children. The average age at diagnosis is about 3 to 4 years 2. It becomes less common as children grow older and is uncommon after age 6. It’s very rare in adults, although cases have been reported 11.

Wilms tumors are slightly more common in girls than in boys. The risk of Wilms tumor is slightly higher in African American children than in white children and is lowest among Asian American children 10.

Treatment for Wilms tumor usually involves surgery and chemotherapy, and sometimes radiation therapy. Treatments may vary by the stage of the cancer. Because Wilms tumor is rare, your child’s doctor may recommend that you seek treatment at a children’s cancer center that has experience treating this type of cancer.

Over the years, advancements in the diagnosis and treatment of Wilms tumor have greatly improved the outlook (prognosis) for children with this kidney cancer 12. With appropriate treatment, the outlook for most children with Wilms’ tumor is very good 13.

Table 1. Syndromes and conditions associated with Wilms tumor

| Syndrome/Condition | Gene | Overgrowth Phenotype | Non-Overgrowth Phenotype |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Risk of Wilms Tumor (>20%) | |||

| WAGR syndrome | WT1 deletion | X | |

| Denys-Drash syndrome | WT1 missense mutation | X | |

| Perlman syndrome | DIS3L2 mutation | X | |

| Fanconi anemia with biallelic mutations in BRCA2 (FANCD1) or PALB2 (FANCN) | BRCA2, PALB2 | X | |

| Premature chromatid separation/mosaic variegated aneuploidy | Biallelic BUB1B or TRIP13 mutation | X | |

| Moderate Risk of Wilms Tumor (5%–20%) | |||

| Frasier syndrome | WT1 intron 9 splice mutation | X | |

| Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome | Uniparental disomy or H19 epimutation | X | |

| Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome | GPC3 mutation | X | |

| Low Risk of Wilms Tumor (<5%) | |||

| Bloom syndrome | Biallelic BLM mutation | X | |

| DICER1 syndrome | DICER1 mutation | X | |

| Li-Fraumeni syndrome | TP53, CHEK2 | X | |

| Isolated hemihyperplasia | X | ||

| Hyperparathyroidism-jaw tumor syndrome | CDC73 (also known as HRPT2) mutation | X | |

| MULIBREY nanism syndrome | TRIM37 mutation | X | |

| PIK3CA-related segmental overgrowth including CLOVES syndrome | PIK3CA mutation | X | |

| 9q22.3 microdeletion syndrome | 9q22.3 | X | |

| Sotos syndrome | NSD1 | X | |

| Familial Wilms tumor | FWT1 | X | |

| FWT2 | |||

| Genitourinary anomalies | WT1 | X | |

| Sporadic aniridia | WT1 | X | |

| Trisomy 18 | X | ||

Footnotes: CLOVES = congenital lipomatous overgrowth, vascular malformations, epidermal nevi, and skeletal/spinal abnormalities; MULIBREY = distinctive abnormalities of the (MU)scles, (LI)ver, (BR)ain, and (EY)es; WAGR = Wilms tumor, aniridia, genitourinary anomaly, and mental retardation.

[Source 14 ]Can Wilms tumor be found early?

Wilms tumors are usually found when they start to cause symptoms such as swelling in the abdomen (belly), but by this point they have often grown quite large. They can be found earlier in some children with tests such as an ultrasound of the abdomen. But because Wilms tumors are rare, it’s not practical to use ultrasound exams to screen all children for them. Screening is testing for a disease like cancer in people with no signs or symptoms. There are no blood tests or other tests that are useful in screening otherwise healthy children for Wilms tumors.

On the other hand, screening is very important for children who have syndromes or birth defects known to be linked to Wilms tumors (see Table 1). For these children, most doctors recommend physical exams by a specialist and ultrasound exams of the kidneys on a regular basis (for example, about every 3 or 4 months at least until the age of 7) to find any kidney tumors when they are still small and have not yet spread to other organs.

Wilms tumor can also run in families, although this is rare. Talk to your doctor if you have any relatives who have had a Wilms tumor. If you do, the children in your family may need to have regular ultrasound exams of the abdomen. If a person is known to have a WT1 gene mutation, genetic testing can be done to see if they have passed the mutation on to their children. This can be done even before birth.

Kidneys anatomy

The main job of the kidneys is filtering blood coming in from the renal arteries to rid the body of excess water, salt, and waste products. These substances become urine. Urine leaves the kidneys through long, slender tubes called ureters that connect to the bladder. Urine flows down the ureters into the bladder, and is stored there until the person urinates. Another tube called the urethra carries the urine from the bladder out of the body.

Inside the kidney, tiny networks of tubes called nephrons filter the blood. Inside the nephrons, waste products move from the small blood vessels into urine collecting tubes. As blood passes through the nephrons all unwanted water and waste gets taken away. Chemicals that your body needs are kept and returned to the bloodstream. The urine gathers in an area called the renal pelvis at the center of each kidney. From here it drains down a tube called the ureter and into the bladder.

The kidneys also have other jobs:

- They help control blood pressure by making a hormone called renin.

- They help make sure the body has enough red blood cells by making a hormone called erythropoietin. This hormone tells the bone marrow to make more red blood cells.

Your kidneys are important, but you actually need less than one complete kidney to do all of its basic functions. Many people in the United States live normal, healthy lives with just one kidney.

Figure 1. Kidney location

Figure 2. Kidney location (transverse section)

Figure 3. Kidney anatomy

Types of Wilms tumor

Wilms tumors (nephroblastoma) are grouped into 2 major types based on how they look under a microscope (their histology):

- Favorable histology: Although the cancer cells in these tumors don’t look quite normal, there is no anaplasia (see next paragraph). More than 9 of 10 Wilms tumors have a favorable histology. The chance of curing children with these tumors is very good.

- Unfavorable histology (anaplastic Wilms tumor): In these tumors, the look of the cancer cells varies widely, and the cells’ nuclei (the central parts that contain the DNA) tend to be very large and distorted. This is called anaplasia. In general, tumors in which the anaplasia is spread throughout the tumor (known as diffuse anaplasia) are harder to treat than tumors in which the anaplasia is limited just to certain parts of the tumor (known as focal anaplasia).

Other types of kidney cancers in children

Most kidney cancers in children are Wilms tumors, but in rare cases children can develop other types of kidney tumors.

- Mesoblastic nephroma

These tumors usually appear in the first few months of life. Children are usually cured with surgery, but sometimes chemotherapy is given as well. These tumors sometimes come back soon after treatment, so children who have had these tumors need to be watched closely for the first year afterward.

- Clear cell sarcoma of kidney

These tumors are much more likely to spread to other parts of the body than Wilms tumors, and they are harder to cure. Because these tumors are rare, treatment is often given as part of a clinical trial. It’s usually much like the intensive treatment used for Wilms tumors with unfavorable histology.

- Malignant rhabdoid tumor of the kidney

These tumors occur most often in infants and toddlers. They tend to spread to other parts of the body quickly, and most have already spread by the time they are found, which makes them hard to cure. Because these tumors are rare, treatment is often given as part of a clinical trial, and usually includes chemotherapy with several different drugs.

- Renal cell carcinoma

This is the most common type of kidney cancer in adults, but it also accounts for a small number of kidney tumors in children. It’s rare in young children, but it’s actually more common than Wilms tumor in older teens.

Surgery to remove the kidney is the main treatment for these cancers if it can be done. The outlook for these cancers depends largely on the extent (stage) of the cancer at the time it’s found, whether it can be removed completely with surgery, and its subtype (based on how the cancer cells look under a microscope). If the cancer is too advanced to be removed by surgery, other types of treatment may be needed.

Wilms tumor causes

Although there is a clear link between Wilms tumors and certain birth defect syndromes and genetic changes, most children with this type of cancer do not have any known birth defects or inherited gene changes.

Researchers do not yet know exactly why some children get Wilms tumors, but they have made great progress in understanding how normal kidneys develop, as well as how this process can go wrong, leading to a Wilms tumor.

The kidneys develop very early as a fetus grows in the womb. Changes (mutations) in certain genes in early kidney cells (nephroblasts) can lead to problems as the kidneys develop. Some of the cells that are supposed to develop into mature kidney cells stay as early kidney cells instead. Clusters of these early kidney cells sometimes remain after the baby is born. Usually, these cells mature by the time the child is 3 to 4 years old. But if this doesn’t happen, the cells might somehow begin to grow out of control, which might result in a Wilms tumor.

In rare cases, the errors in DNA that lead to Wilms’ tumor are passed from a parent to the child. In most cases, there is no known connection between parents and children that may lead to cancer.

Scientists have found that some Wilms tumors have changes in specific genes 15, 16:

- A small number of Wilms tumors have changes in or loss of the WT1 or WT2 genes, which are tumor suppressor genes found on chromosome 11. Tumor suppressor genes are genes that slow down cell division or cause cells to die at the right time. Changes in WT1 or WT2 genes and some other genes on chromosome 11 can lead to overgrowth of certain body tissues. This may explain why some other growth abnormalities, like those described in Risk Factors for Wilms Tumors, are sometimes found along with Wilms tumors.

- In a small number of Wilms tumors there is a change in a tumor suppressor gene known as WTX (also called AMER1), which is found on the X chromosome at Xq11.1. WTX is altered in 15% to 20% of Wilms tumor cases 18, 20, 21, 19. Germline mutations in WTX cause an X-linked sclerosing bone dysplasia, osteopathia striata congenita with cranial sclerosis 22. Despite having germline WTX mutations, individuals with osteopathia striata congenita are not predisposed to tumor development 22. The WTX protein appears to be involved in both the degradation of beta-catenin and in the intracellular distribution of APC protein 23, 24. WTX is most commonly altered by deletions involving part or all of the WTX gene, with deleterious point mutations occurring less commonly 18. Most Wilms tumor cases with WTX alterations have epigenetic 11p15 abnormalities 18. WTX gene alterations are equally distributed between males and females, and WTX inactivation has no apparent effect on clinical presentation or prognosis 19.

- Another gene that is sometimes altered in Wilms tumor cells is known as CTNNB1, which is on chromosome 3.

- CTNNB1 gene mutation reported occured in 15% of patients with Wilms tumor 18, 16. These CTNNB1 mutations result in activation of the WNT pathway, which plays a prominent role in the developing kidney 25. CTNNB1 mutations commonly occur with WT1 mutations, and most cases of Wilms tumor with WT1 mutations have a concurrent CTNNB1 mutation 26, 18. Activation of beta-catenin in the presence of intact WT1 protein appears to be inadequate to promote tumor development because CTNNB1 mutations are rarely found in the absence of a WT1 or WTX mutation, except when associated with a MLLT1 mutation 23, 27. CTNNB1 mutations appear to be late events in Wilms tumor development because they are found in tumors but not in nephrogenic rests 28.

It’s not clear exactly what causes these genes to be altered. Approximately one-third of Wilms tumor cases involve mutations in WT1, CTNNB1, or WTX 19, 27. Another subset of Wilms tumor cases results from mutations in miRNA processing genes (miRNAPG), including DROSHA, DGCR8, DICER1, and XPO5 29, 30. Other genes critical for early renal development that are recurrently mutated in Wilms tumor include SIX1 and SIX2 (transcription factors that play key roles in early renal development) 29, 30, EP300, CREBBP, and MYCN 16. Of the mutations in Wilms tumors, 30% to 50% appear to converge on the process of transcriptional elongation in renal development and include the genes MLLT1, BCOR, MAP3K4, BRD7, and HDAC4 16. Anaplastic Wilms tumor is characterized by the presence of TP53 mutations.

Several other gene or chromosome changes have been found in Wilms tumor cells. Typically, more than one gene change is needed to cause cancer. None of the gene changes found so far are seen in all Wilms tumors. There are also likely to be other gene changes that have not yet been found.

Researchers now understand some of the gene changes that can occur in Wilms tumors, but it’s still not clear what causes these changes. Some gene changes can be inherited, but most Wilms tumors are not the result of known inherited syndromes.

Some gene changes may just be random events that sometimes happen inside a cell, without having an outside cause. There are no known lifestyle-related or environmental causes of Wilms tumors, so it’s important to know that there is nothing these children or their parents could have done to prevent these cancers.

Risk factors for Wilms tumor

A risk factor is anything that affects the chance of having a disease such as cancer. Different cancers have different risk factors. Most Wilms tumors have no clear cause, but there are some factors that affect risk.

So far research has not found any strong links between Wilms tumor and environmental factors, either during a mother’s pregnancy or after a child’s birth.

Age

Wilms tumors are most common in young children, with the average age being about 3 to 4 years. They are less common in older children, and rare in adults.

Race

In the United States, the risk of Wilms tumor is slightly higher in African-American children than in white children and is lowest among Asian-American children. The reason for this is not known.

Gender

Wilms tumors are slightly more common in girls than in boys.

Family history of Wilms tumor

About 1% to 2% of children with Wilms tumors have one or more relatives with the same cancer. Scientists think that these children inherit chromosomes with an abnormal or missing gene from a parent that increases their risk of developing Wilms tumor.

Children with a family history of Wilms tumors are slightly more likely to have tumors in both kidneys. Still, in most children only one kidney is affected.

Certain genetic syndromes or birth defects

There is a strong link between Wilms tumors and certain kinds of birth defects. About 1 child in 10 with Wilms tumor also has birth defects. Most birth defects linked to Wilms tumors occur in syndromes. A syndrome is a group of symptoms, signs, malformations, or other abnormalities that occur together in the same person.

Elevated rates of Wilms tumor are observed in patients with a number of genetic disorders, including WAGR (Wilms tumor, aniridia, genitourinary anomalies, and mental retardation) syndrome, Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, hemihypertrophy, Denys-Drash syndrome, and Perlman syndrome 31. Other genetic causes that have been observed in familial Wilms tumor cases include germline mutations in REST and CTR9 32, 33.

Syndromes linked to Wilms tumor include:

WAGR syndrome

WAGR stands for the first letters of the physical and mental problems linked with this syndrome (although not all children have all of them):

- Wilms tumor

- Aniridia (complete or partial lack of the iris [colored area] of the eyes)

- Genitourinary tract abnormalities (defects of the kidneys, urinary tract, penis, scrotum, clitoris, testicles, or ovaries)

- Mental Retardation

Children with WAGR syndrome have about a 30% to 50% chance of having a Wilms tumor. The cells in children with WAGR syndrome are missing part of chromosome 11, where the WT1 gene is normally found. Children with WAGR tend to get Wilms tumors at an earlier age and often have tumors in both kidneys.

Denys-Drash syndrome and Frasier syndrome

These rare syndromes have also been linked to changes (mutations) in the WT1 gene.

In Denys-Drash syndrome, the kidneys become diseased and stop working when the child is very young. Wilms tumors usually develop in the diseased kidneys. The reproductive organs don’t develop normally, and boys may be mistaken for girls. Because the risk of Wilms tumors is very high, doctors often advise removing the kidneys soon after Denys-Drash syndrome is diagnosed.

In Frasier syndrome the kidneys are also diseased, but they usually keep working into adolescence. As with Denys-Drash syndrome, the reproductive organs don’t develop normally. Children with Frasier syndrome are also at increased risk for Wilms tumors, although they are at even higher risk for cancers in the reproductive organs.

Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome

Children with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome tend to be big for their age. They also have larger than normal internal organs and often have an enlarged tongue. They may have an oversized arm and/or leg on one side of the body (called hemihypertrophy), as well as other medical problems. They have about a 5% risk of having Wilms tumors (or, less often, other cancers that develop during childhood). Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome is caused by a defect in chromosome 11 that affects the WT2 gene.

Other syndromes

Less often, Wilms tumor has been linked to other syndromes, including:

- Perlman syndrome

- Sotos syndrome

- Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome

- Bloom syndrome

- Li-Fraumeni syndrome

- Trisomy 18

Certain birth defects

Wilms tumor is also more common in children with certain birth defects (without known syndromes):

- Aniridia (complete or partial lack of the iris [colored area] of the eyes)

- Hemihypertrophy (an oversized arm and/or leg on one side of the body)

- Cryptorchidism (failure of the testicles to descend into the scrotum) in boys

- Hypospadias (defect in boys where the urinary opening is on the underside of the penis)

Wilms tumor prevention

The risk of many adult cancers can be reduced with certain lifestyle changes (such as staying at a healthy weight or quitting smoking), but at this time there are no known ways to prevent most cancers in children.

The only known risk factors for Wilms tumors (age, race, gender, and certain inherited conditions) can’t be changed. There are no known lifestyle-related or environmental causes of Wilms tumors, so at this time there is no way to protect against most of these cancers. Experts think these cancers come from cells that were in the fetus but failed to develop into mature kidney cells. This doesn’t seem to be caused by anything a mother could avoid during pregnancy.

In some very rare cases, such as in children with Denys-Drash syndrome who are almost certain to develop Wilms tumors, doctors may recommend removing the kidneys at a very young age (with a donor kidney transplant later on) to prevent tumors from developing.

Wilms tumor symptoms

Signs and symptoms of Wilms tumor vary widely, and before being diagnosed with Wilms tumor most children do not show any signs of having cancer, and usually act and play normally. Wilms tumor often grow quite large before causing any symptoms. Often, a parent may discover a firm, smooth lump in the child’s abdomen. It is not uncommon for the mass to grow quite large before it is discovered ― the average Wilms tumor is 1 pound at diagnosis.

Swelling or a hard mass in the abdomen (belly): This is often the first sign of a Wilms tumor. Parents may notice this while bathing or dressing the child. It feels firm and is often large enough to be felt on both sides of the belly. It’s usually not painful, but it might cause belly pain in some children.

Other possible symptoms. Some children with Wilms tumor may also have:

- Fever

- Nausea or vomiting or both

- Loss of appetite

- Shortness of breath

- Constipation

- Blood in the urine

Wilms tumors can also sometimes cause high blood pressure (hypertension). This does not usually cause symptoms on its own, but in rare cases blood pressure can get high enough to cause problems such as headaches, bleeding inside the eye, or even a change in consciousness.

Many of the signs and symptoms above are more likely to be caused by something other than a kidney tumor. Still, if your child has any of these symptoms, check with your child’s doctor so that the cause can be found and treated, if needed.

Even though Wilms tumors often are large when found, most have not spread to other areas of the body. This makes it easier to successfully treat than if the cancer cells have spread (metastasized) to other parts of the body.

Wilms tumor diagnosis

Wilms tumors are usually found when a child is brought to a doctor because of symptoms he or she is having. The doctor might suspect a child has a Wilms tumor because of the physical exam or other test results, but the diagnosis can only be made for certain by taking out a small piece of the tumor and looking at it under a microscope.

Medical history and physical exam

If your child has signs or symptoms that suggest he or she may have a kidney tumor, the doctor will want to get a complete medical history to learn more about the symptoms and how long they have been there. The doctor may also ask if there’s a family history of cancer or birth defects, especially in the genitals or urinary system.

The doctor will examine your child for possible signs of a kidney tumor or other health problems. The focus will probably be on the abdomen (belly) and on any increase in blood pressure, which is another possible sign of a kidney tumor. Blood and urine samples might also be collected and tested.

Several tests are used to confirm a Wilms tumor diagnosis and determine the stage of the disease. Tests that might be used include:

- Ultrasonography (ultrasound or US), usually the first tool used to diagnose a Wilms tumor (or another type of tumor in the abdomen), uses sound waves instead of X-rays to generate an image of the area doctors wish to view. It’s also very useful when looking for tumor growing into the main veins coming out of the kidney. This can help in planning for surgery, if it’s needed.

- Computed tomography (CT or CAT scan) produces a detailed cross-sectional view of an organ through X-rays. It is extremely useful in detecting tumors and determining whether cancer has spread to other areas. It’s also helpful for checking whether a cancer has grown into nearby veins or has spread to organs beyond the kidney, such as the lungs. Your child will need to lie very still on a table while the scans are being done. Younger children may be given medicine to help keep them calm or even asleep during the test to help make sure the pictures are clear.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses radio waves and strong magnets to produce detailed pictures of the internal parts of the body. This provides more intricate images that allow doctors to see if the cancer has invaded any major blood vessels near the kidney. For example, it might be done if there’s a chance that a kidney tumor might have reached a major vein (the inferior vena cava) in the abdomen. An MRI scan might also be used to look for possible spread of cancer to the brain or spinal cord if doctors are concerned the cancer may have spread there. Your child may have to lie inside a narrow tube, which is confining and can be distressing. The test also requires a person to stay still for several minutes at a time. Younger children may be given medicine to help keep them calm or even asleep during the test.

- X-rays are used to look for any metastasized areas, especially in the lungs. This test might not be needed if a CT scan of the chest is done.

- Bone scans use small amounts of radioactive material to highlight areas of diseased bone, if any exist.

- Laboratory tests such as blood tests and urinalysis check the general health of a patient and to detect any adverse side effects (such as low red or white blood cell counts) of the treatment. A urine sample may be tested (urinalysis) to see if there are problems with the kidneys. Urine may also be tested for substances called catecholamines. This is done to make sure your child doesn’t have another kind of tumor called neuroblastoma. (Neuroblastomas often start in the adrenal glands, which are just on top of each kidney.)

- Kidney biopsy/surgery. Most of the time, imaging tests can give doctors enough information to decide if a child probably has a Wilms tumor, and therefore if surgery should be done. But the actual diagnosis of Wilms tumor is made when a small piece of the tumor is removed and checked under a microscope. The cells in Wilms tumors have a distinct appearance when looked at this way. Doctors also look at the sample to determine the histology of the Wilms tumor (favorable or unfavorable). In most cases, a sample is removed during surgery to treat the tumor. Sometimes if the doctors are less certain about the diagnosis or if they aren’t sure the tumor can be removed completely, a sample of the tumor may be taken during a biopsy as a separate procedure before surgery.

The chance of Wilms tumor being hereditary (“running in the family”) is so rare that there is no test to screen those who may pass the disease onto their offspring. However, certain genetic factors like birth defect syndromes can increase the likelihood of developing the disease. Those with a family history or personal history of Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome (a condition associated with larger-than-normal internal organs), WAGR (marked by defects of the iris, kidneys, urinary tract, or genitalia), or Denys-Drash syndrome (a defect of the genitalia) are at risk.

Kids with risk factors for Wilms tumor should be screened for the disease through an ultrasound every 3 months until they reach at least age 8 years 34, 35. Those at high risk may get undergo screening until they’re a little older.

Wilms tumor pathology outlines

Grossly, Wilms tumors are usually well-circumscribed and have a pseudo-capsule. Histologically, Wilms tumor is divided into “favorable” and “unfavorable” histologies.

“Favorable” Histology: Ninety percent of Wilms tumors will demonstrate “favorable” histology, which generally has a better prognosis. Classical histological features of a “favorable” Wilms tumor include a triphasic pattern of blastema, epithelial, and stromal tissues. The blastema is the most undifferentiated and possibly the most malignant component. It consists of collections of small, round blue cells with very active mitotic activity and overlapping nuclei.

The epithelial component can demonstrate wide variations in differentiation from an early tubular formation with primitive epithelial rosette-like structures to differentiating tubules or glomeruli-like structures, representing nephrogenesis at different developmental stages.

The stromal component may include densely packed undifferentiated mesenchymal cells or loose cellular myxoid areas. The latter areas may be difficult to distinguish from non-tumorous stroma associated with chemotherapy-induced change. Heterologous differentiation of neoplastic stroma in the form of well-differentiated smooth or skeletal muscle cells, fat tissue, cartilage, bone, and even glial tissue is present in some cases, especially in tumors that have undergone preoperative chemotherapy.

Even with “Favorable” histology, the loss of heterozygosity at 1p and 16q loci tend to have a worse prognosis. For this reason, when Wilms tumor tissue is available, it should be checked cytogenetically for 1p and 16q deletions.

“Unfavorable” Histology: Wilms tumors with “unfavorable” histology will demonstrate much higher degrees of anaplasia and are associated with a relatively poorer prognosis and survival.

Anaplastic Wilms’ tumors account for 5–8% of all Wilms tumors, and the majority of patients with anaplastic Wilms tumor are older than those with non-anaplastic Wilms tumor. Anaplasia is associated with a poor response to treatment.

The criteria necessary for the diagnosis of anaplasia are the presence of large, atypical multipolar mitotic figures and significantly enlarged and hyperchromatic nuclei 36. These tumors are generally aneuploid. Anaplasia may be focal or diffuse. Focal anaplasia means that there is a localized and definitely completely excised area with anaplastic features. All other cases where anaplasia is found should be regarded as diffuse anaplasia. Diffuse anaplasia is regarded as the only unfavourable histological feature in Wilms tumors undergoing primary nephrectomy. Anaplasia is responsible for adverse outcome, especially in the cases with advanced tumour stage; thus, its recognition is essential for the prognosis and treatment. Because anaplasia is regarded as a chemo-resistant cell clone, it may be easier to detect it in pre-treated cases due to loss of other chemo-sensitive elements. Anaplastic tumours often express p53 on immunohistochemical staining and bear mutants in the TP53 gene 37. TP53 mutation has been shown to compromise patients’ survival, overall and event-free, and therefore has the potential as an adverse prognostic factor combined with anaplastic morphological features 38. Dysregulation of MYCN gene in Wilms tumors with anaplastic histology has also been reported to be involved in the development of tumours with adverse outcome 39.

Wilms tumor differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of Wilms tumor can be tricky. While Wilms tumor is the most common childhood kidney tumor, the second most common is clear cell renal sarcoma. The clear cell renal sarcoma prognosis is not as good as Wilms tumor as it has higher mortality and relapse rates. It often metastasizes to bone 40. Histological appearance can sometimes be similar to Wilms tumor which can lead to a misdiagnosis 41.

Rhabdoid renal tumors are highly malignant and are most often seen before age two and almost never in children older than five years. It is often widely metastatic at the time of initial presentation and has a very poor prognosis with an 80% mortality rate within one year of diagnosis.

Congenital mesoblastic nephroma is typically found in the first year of life, most often by ultrasound. Hypertension and elevated renin levels usually accompany it.

Renal cell carcinoma is rare in the pediatric age group. However, when present, it is often at a more advanced stage than in adults. Neuroblastoma patients who are post-radiation and post-chemotherapy are at increased risk.

Renal medullary carcinoma is a very aggressive and dangerous cancer that is found almost exclusively in individuals with sickle cell disease, usually trait. It tends to be highly locally invasive and metastasizes early.

Wilms tumor staging

The stage of a cancer describes how far it has spread. Your child’s treatment and prognosis (outlook) depend, to a large extent, on the cancer’s stage. Staging is based on the results of the physical exam and imaging tests (ultrasound, CT scans, etc.), as well as on the results of surgery to remove the tumor, if it has been done.

Children’s Oncology Group (COG) staging system

A staging system is a standard way for the cancer care team to sum up the extent of the tumor. In the United States, the Children’s Oncology Group staging system is used most often to describe the extent of spread of Wilms tumors. This system describes Wilms tumor stages using Roman numerals I through V (1 through 5).

Stage 1

The tumor was contained within one kidney and was removed completely by surgery. The tissue layer surrounding the kidney (the renal capsule) was not broken during surgery. The cancer had not grown into blood vessels in or next to the kidney. The tumor was not biopsied before surgery to remove it.

About 40% to 45% of all Wilms tumors are stage 1.

Stage 2

The tumor has grown beyond the kidney, either into nearby fatty tissue or into blood vessels in or near the kidney, but it was removed completely by surgery without any apparent cancer left behind. Nearby lymph nodes (bean-sized collections of immune cells) do not contain cancer. The tumor was not biopsied before surgery.

About 20% of all Wilms tumors are stage 2.

Stage 3

This stage refers to Wilms tumors that may not have been removed completely. The cancer remaining after surgery is limited to the abdomen (belly). One or more of the following features may be present:

- The cancer has spread to lymph nodes in the abdomen or pelvis but not to more distant lymph nodes, such as those inside the chest.

- The cancer has grown into nearby vital structures so the surgeon could not remove it completely.

- Deposits of tumor (tumor implants) are found along the inner lining of the abdominal space.

- Cancer cells are found at the edge of the sample removed by surgery, a sign that some of the cancer still remains after surgery.

- Cancer cells “spilled” into the abdominal space before or during surgery.

- The tumor was removed in more than one piece – for example, the tumor was in the kidney and in the nearby adrenal gland, which was removed separately.

- A biopsy of the tumor was done before it was removed with surgery.

About 20% to 25% of all Wilms tumors are stage 3.

Stage 4

The cancer has spread through the blood to organs away from the kidneys such as the lungs, liver, brain, or bones, or to lymph nodes far away from the kidneys.

About 10% of all Wilms tumors are stage 4.

Stage 5

Tumors are found in both kidneys at diagnosis.

About 5% of all Wilms tumors are stage 5.

Tumor histology

The other main factor in determining the prognosis and treatment for a Wilms tumor is the tumor’s histology, which is based on how the tumor cells look under a microscope. The histology can be either favorable or unfavorable (anaplastic).

Wilms tumor prognosis

Overall, about 9 of 10 children with Wilms tumor are cured. A great deal of progress has been made in treating this disease. Much of this progress in the United States has been because of the work of the National Wilms Tumor Study Group (now part of the Children’s Oncology Group), which runs clinical trials of new treatments for children with Wilms tumor. Today, most children with this cancer are treated in a clinical trial to try to improve on what doctors believe is the best treatment. The goal of these studies is to find ways to cure as many children as possible while limiting side effects by giving as little treatment as needed.

Because of major advances in treatment, most children treated for Wilms tumor are now surviving into adulthood. Doctors have learned that treatment can affect children’s health later in life, so watching for health effects as they get older has become more of a concern in recent years.

Just as the treatment of childhood cancer requires a very specialized approach, so does the care and follow-up after treatment. The earlier any problems can be recognized, the more likely it is they can be treated effectively. Young people treated for Wilms tumor are at risk, to some degree, for several possible late effects of their cancer treatment. It’s important to discuss what these possible effects might be with your child’s medical team so you know what to watch for and report to the doctor.

The risk of late effects depends on a number of factors, such as the specific treatments the child has, the doses of treatment, and the age of the child when being treated. These late effects may include:

- Reduced kidney function

- Heart or lung problems after getting certain chemotherapy drugs or radiation therapy to these parts of the body

- Slowed or delayed growth and development

- Changes in sexual development and ability to have children, especially in girls

- Increased risk of second cancers later in life (rare)

There may be other possible complications from treatment as well. Your child’s doctor should carefully review any possible problems with you before your child starts treatment.

Along with physical side effects, some childhood cancer survivors might have emotional or psychological issues. They might also have problems with normal functioning and school work. These can often be addressed with support and encouragement. If needed, doctors and other members of the health care team can recommend special support programs and services to help children after cancer treatment.

Long-term follow-up care

To help increase awareness of late effects and improve follow-up care of childhood cancer survivors throughout their lives, the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) has developed long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood cancers. These guidelines can help you know what to watch for, what type of screening tests should be done to look for problems, and how late effects can be treated.

Ask your child’s health care team about possible long-term complications and make sure there’s a plan in place to watch for these problems and treat them, if needed. To learn more, ask your child’s doctors about the COG survivor guidelines. You can also read them online at http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org. You may want to discuss them with your child’s doctor.

Wilms tumor survival rate

Survival rates are often used by doctors as a standard way of discussing a person’s prognosis (outlook). These numbers tell you what portion of people in a similar situation (such as with the same type and stage of cancer) are still alive a certain amount of time after they were diagnosed. They can’t tell you exactly what will happen with any person, but they may help give you a better understanding about how likely it is that treatment will be successful. Some people find survival rates helpful, but some people might not.

For Wilms tumors, survival is often measured using a 4-year survival rate. This refers to the percentage of children who live at least 4 years after their cancer is diagnosed. For example, a 4-year survival rate of 95% means that an estimated 95 out of 100 children who have that cancer are still alive 4 years after being diagnosed. Of course, many children live much longer than 4 years (and many are cured).

To get 4-year survival rates, doctors have to look at children who were treated at least 4 years ago. Improvements in treatment since then may result in a better outlook for children now being diagnosed with Wilms tumors.

Remember, survival rates are estimates only and they can’t predict what will happen in a particular child’s case. Each child’s outlook can vary based on a number of factors specific to them. The most important factors in determining a child’s outlook are the stage and histology of the tumor. Histology refers to how the cancer cells look under the microscope.

Furthermore, other factors can also affect a child’s outlook, such as the child’s age and how well the tumor responds to treatment.

Even when taking other factors into account, survival rates are only rough estimates. Your child’s doctor can tell you how the numbers below might apply, as he or she knows your child’s situation best.

Table 2. Wilms tumor survival rate

| Wilms Tumor 4-year Survival Rates | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor Stage | Favorable Histology | Focal Anaplastic | Diffuse Anaplastic |

| 1 | 95% – 100% | 85% – 90% | 75% – 80% |

| 2 | 95% – 100% | 80% – 85% | 80% – 85% |

| 3 | 95% – 100% | 75% – 90% | 50% – 70% |

| 4 | 85% – 90% | 70% – 75% | 30% – 45% |

| 5 | 95% – 100% | 95% – 100% | 65% – 70% |

Footnotes: These survival rates are based on the results of the National Wilms Tumor Studies, which included most of the children treated in the United States in the last few decades. Some of these rates are based on only small numbers of children, so it’s hard to know how accurate they are.

[Source 42]Wilms tumor treatment

Treatment is determined by many factors, the most important being the stage of the cancer at diagnosis, and the condition, or histology, of the cancer cells when observed under a microscope. “Favorable” histology is associated with a good chance of a cure; tumors with “unfavorable” histology are more aggressive and difficult to cure. About 95% of Wilms tumors have favorable histology.

Other factors can influence treatment as well, including:

- The child’s age

- If the tumor cells have certain chromosome changes

- The size of the main tumor

Because Wilms tumors are rare, few doctors outside of those in children’s cancer centers have much experience in treating them. Children with Wilms tumors are treated with a team approach that includes the child’s pediatrician as well as specialists at a child’s cancer center. For Wilms tumors, the doctors on this team often include:

- A pediatric surgeon or pediatric urologist (doctor who treats urinary system problems in children [and genital problems in boys])

- A pediatric oncologist (doctor who uses chemotherapy and other medicines to treat childhood cancers)

- A pediatric radiation oncologist (doctor who uses radiation therapy to treat cancer in children)

Doctors use a staging system to describe the extent of a metastasized tumor. It is extremely useful in determining prognosis (possibility for a cure) and the best course of treatment. For example, a child with very aggressive disease should be given an intensive regimen of medication to achieve the best chance for a cure. A child with less-invasive disease should be given the least amount needed to reduce long-term side effects from toxicity.

The stages are:

- Stage 1: Cancer is found in one kidney only and can be completely removed by surgery. About 41% of all Wilms tumors are stage I.

- Stage 2: Cancer has spread beyond the kidney to the surrounding area, but can be completely removed by surgery. About 23% are stage II.

- Stage 3: Cancer has not spread beyond the abdomen, but cannot be completely removed by surgery. About 23% are stage III.

- Stage 4: Cancer has spread to distant parts of the body; most commonly, the lungs, liver, bone, and/or brain. About 10% are stage IV.

- Stage 5: Cancer is found in both kidneys at diagnosis (also called bilateral tumors). About 5% are stage V.

After your child’s tumor is found and its stage and histology are determined, the cancer care team will discuss treatment options with you. It’s important to discuss all of the options as well as their possible side effects with your child’s doctors so you can make an informed decision.

The main types of treatment for Wilms tumor are:

- Surgery for all children

- Chemotherapy for almost all children

- Radiation therapy for some children

Most children will get more than one type of treatment.

In the United States, doctors prefer to use surgery as the first treatment in most cases, and then give chemotherapy (and possibly radiation therapy) afterward 43. In Europe, doctors prefer to start the chemotherapy before surgery. The results from these approaches seem to be about the same.

The first goal of treatment is to remove the primary (main) tumor, even if the cancer has spread to distant parts of the body. Sometimes the tumor might be hard to remove because it is very large, it has spread into nearby blood vessels or other vital structures, or it’s in both kidneys. For these children, doctors might use chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or a combination of the 2 to try to shrink the tumor(s) before surgery.

If any cancer is left after surgery, radiation therapy or more surgery may be needed.

Surgery

Surgery is most often used to treat Wilms tumor. It’s important that it is done by a surgeon who specializes in operating on children and has experience in treating these cancers. For stages I through IV, a radical nephrectomy ― removal of the cancer along with the entire kidney, ureter (tube that carries urine from the kidney to the bladder), adrenal gland (hormone-producing gland that sits on top of the kidney), and surrounding fatty tissue ― is done.

Since stage V patients have cancer involvement in both kidneys, removing both kidneys would result in kidney failure and the need for a kidney transplant. As a result, surgeons usually take out as much of the cancer as possible and preserve as much healthy kidney tissue as they can to avoid an organ transplant.

Surgery to remove all or part of a kidney

Treatment for Wilms’ tumor may begin with surgery to remove all or part of a kidney (nephrectomy). Surgery is also used to confirm the diagnosis — the tissue removed during surgery is sent to a lab to determine whether it’s cancerous and what type of cancer is in the tumor.

Surgery for Wilms’ tumor may include:

- Removing part of the affected kidney. Partial nephrectomy (nephron-sparing surgery) involves removal of the tumor and a small part of the kidney tissue surrounding it. Partial nephrectomy may be an option if the cancer is very small or if your child has only one functioning kidney.

- Removing the affected kidney and surrounding tissue. In a radical nephrectomy, doctors remove the kidney and surrounding tissues, including part of the ureter and sometimes the adrenal gland. Nearby lymph nodes also are removed. The remaining kidney can increase its capacity and take over the job of filtering the blood.

- Removing all or part of both kidneys. If the cancer affects both kidneys, the surgeon removes as much cancer as possible from both kidneys. In a small number of cases, this may mean removing both kidneys, and your child would then need kidney dialysis. If a kidney transplant is an option, your child would no longer need dialysis.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (chemo) uses powerful drugs to kill cancer cells throughout the body. Treatment for Wilms’ tumor usually involves a combination of drugs, given through a vein (IV) or through a central venous catheter (a thin tube inserted into a large blood vessel during surgery), that work together to kill cancer cells.

The chemo drugs used most often to treat Wilms tumors are:

- Actinomycin D (dactinomycin)

- Vincristine

For Wilms tumors at more advanced stages, those with anaplastic histology, or tumors that recur (come back) after treatment, other drugs might also be used, such as:

- Doxorubicin (Adriamycin)

- Cyclophosphamide

- Etoposide

- Irinotecan

- Carboplatin

What side effects your child may experience will depend on which drugs are used. Common side effects include nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, hair loss and higher risk of infections. Ask the doctor what side effects may occur during treatment, and if there are any potential long-term complications.

Chemotherapy may be used before surgery to shrink tumors and make them easier to remove. It may be used after surgery to kill any cancer cells that may remain in the body. Chemotherapy may also be an option for children whose cancers are too advanced to be removed completely with surgery.

In the United States, chemo is usually given after surgery. Sometimes it may be needed before surgery to shrink a tumor to make the operation possible. In Europe, chemo is given before surgery and continued afterward. In both cases, the type and amount of chemo depend on the stage and histology of the cancer.

For children who have cancer in both kidneys, chemotherapy is administered before surgery. This may make it more likely that surgeons can save at least one kidney in order to preserve kidney function.

Regardless of the stage and histology, all treatment plans usually include both surgery and chemotherapy, and the more advanced stages also may require radiation therapy. Chemotherapy uses drugs (administered either orally or intravenously) to enter the bloodstream, circulate throughout the body, and kill cancerous cells wherever they may be. Radiation uses high-energy X-ray beams to kill specific cells in different areas of the body.

Both treatments have short-term and long-term risks. The side effects of chemo depend on the types and doses of drugs used, and the length of treatment.

Possible short-term side effects can include:

- Hair loss

- Mouth sores

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diarrhea or constipation

- Increased chance of infections (from having too few white blood cells)

- Easy bruising or bleeding (from having too few blood platelets)

- Fatigue or extreme tiredness (from having too few red blood cells)

Along with the effects listed above, some drugs can have specific side effects. For example:

- Vincristine can damage nerves. Some patients may have tingling, numbness, weakness, or pain, particularly in the hands and feet. (This is called peripheral neuropathy.)

- Doxorubicin can damage the heart. The risk of this happening goes up as the total amount of the drug given goes up. Doctors try to limit this risk as much as possible by not giving more than the recommended doses and by checking the heart with a test called an echocardiogram (an ultrasound of the heart) during treatment.

- Cyclophosphamide can damage the bladder, which can cause blood in the urine. The risk of this can be lowered by giving the drug with plenty of fluids and with a drug called mesna, which helps protect the bladder.

Possible long-term effects of treatment are one of the major challenges children might face after cancer treatment. For example:

- If your child is given doxorubicin (Adriamycin), there is a chance it could damage the heart. Your child’s doctor will carefully watch the doses used and will check your child’s heart function with imaging tests.

- Some chemo drugs can increase the risk of developing a second type of cancer (such as leukemia) years after the Wilms tumor is cured. But this small increase in risk has to be weighed against the importance of chemo in treating Wilms tumor.

- Some drugs might also affect fertility (the ability to have children) years later.

Radiation therapy

Depending on the stage of the tumor, radiation therapy (radiotherapy) may be recommended. Radiation therapy uses high-energy beams to kill cancer cells.

Radiation therapy is often part of treatment for more advanced Wilms tumors (stages 3, 4, and 5), as well as for some earlier stage tumors with anaplastic histology. Radiation therapy might be used:

- After surgery to try to make sure all of the cancer is gone

- Before surgery to try to shrink the tumor to make it easier to remove

- Instead of surgery if it can’t be done for some reason

The type of radiation used for Wilms tumors is called external beam radiation therapy (EBRT). Radiation from a source outside the body is focused onto the cancer.

Before treatments start, the radiation team will take careful measurements with imaging tests such as CT or MRI scans to determine the correct angles for aiming the radiation beams and the proper dose of radiation. This planning session is called simulation. Your child may be fitted with a plastic mold that looks like a body cast to keep them in the same position during each treatment so that the radiation can be aimed more accurately.

During radiation therapy, your child is carefully positioned on a table and a large machine moves around your child, precisely aiming energy beams at the cancer.

Only a few centers in the United States, offer proton beam therapy — highly targeted precision beam therapy that destroys cancer while sparing healthy tissue.

Radiation therapy may be used after surgery to kill any cancer cells that weren’t removed during the operation. It may also be an option to control cancer that has spread to other areas of the body, depending on where the cancer has spread.

Radiation is usually given 5 days a week for several weeks. Each treatment is much like getting an x-ray, although the dose of radiation is much stronger. For each session, your child lies on a special table while a machine delivers the radiation from precise angles. Each session lasts about 15 to 30 minutes, with most of the time being spent making sure the radiation is aimed correctly. The actual treatment time is much shorter. The treatment is not painful, but some younger children may be given medicine to make them drowsy or asleep before each treatment to help make sure they stay still.

Radiation is often an important part of treatment, but young children’s bodies are very sensitive to it, so doctors try to use as little as possible to help avoid or limit any problems. Radiation therapy can cause both short-term and long-term side effects, which depend on the dose of radiation and where it’s aimed.

Possible short-term effects include:

- Effects on areas of skin that get radiation can range from mild sunburn-like changes and hair loss to more severe skin reactions.

- Radiation to the abdomen (belly) can cause nausea or diarrhea.

- Radiation therapy can make a child tired, especially after several days or weeks of treatment.

Possible long-term effects include:

- Radiation to the kidney area can damage the kidneys. This is more likely to be a concern in children who need treatment in both kidneys.

- Radiation can slow the growth of normal body tissues (such as bones) that get radiation, especially in younger children. In the past this led to problems such as short bones or a curving of the spine, but this is less likely with the lower doses of radiation used today.

- Radiation to the chest area can affect the heart and lungs. This doesn’t usually cause problems right away, but in some children it might lead to heart or lung problems as they get older.

- In girls, radiation to the abdomen (belly) may damage the ovaries. This might lead to abnormal menstrual cycles or problems getting pregnant or having children later on.

- Radiation slightly increases the risk of developing a second cancer in the area, usually many years after it is given. This doesn’t happen often with Wilms tumors because the amount of radiation used is low.

Clinical trials

Your child’s doctor may recommend participating in a clinical trial. These research studies allow your child a chance at the latest cancer treatments, but they can’t guarantee a cure.

Discuss the benefits and risks of clinical trials with your child’s doctor. The majority of children with cancer enroll in a clinical trial, if available. However, enrollment in a clinical trial is up to you and your child.

Stage 1 Wilms tumor treatment

Stage 1 Wilms tumors are only in the kidney, and surgery has completely removed the tumor along with the entire kidney, nearby structures, and some nearby lymph nodes.

- Favorable histology: Children younger than 2 years with small tumors (weighing less than 550 grams) may not need further treatment after surgery. But they need to be watched closely because the chance the cancer will come back is slightly higher than if they also got chemo. If the cancer does come back, the chemo drugs actinomycin D (dactinomycin) and vincristine (and possibly more surgery) are very likely to be effective at this point. For children older than 2 and for those of any age who have larger tumors, surgery is usually followed by chemo for several months, with the drugs actinomycin D and vincristine. If the tumor cells have certain chromosome changes, the drug doxorubicin (Adriamycin) may be given as well.

- Anaplastic histology: For children of any age who have tumors with anaplastic histology, surgery is usually followed by radiation therapy to the area of the tumor, along with chemo with actinomycin D, vincristine, and possibly doxorubicin (Adriamycin) for several months.

Stage 2 Wilms tumor treatment

Stage 2 Wilms tumors have grown outside the kidney into nearby tissues, but surgery has removed all visible signs of cancer.

- Favorable histology: After surgery, standard treatment is chemo with actinomycin D and vincristine. If the tumor cells have certain chromosome changes, the drug doxorubicin (Adriamycin) may be given as well. The chemo is given for several months.

- Anaplastic histology, with focal (only a little) anaplasia: When the child recovers from surgery, radiation therapy is given over several weeks. When this is finished, chemo (doxorubicin, actinomycin D, and vincristine) is given for about 6 months.

- Anaplastic histology, with diffuse (widespread) anaplasia: After surgery, these children get radiation over several weeks. This is followed by a more intense type of chemo using the drugs vincristine, doxorubicin, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, and carboplatin, along with mesna (a drug that helps protect the bladder from the effects of cyclophosphamide), which is given for about 6 months.

Stage 3 Wilms tumor treatment

Surgery cannot remove these tumors completely because of their size or location or for other reasons. In some cases, surgery may be postponed until other treatments are able to shrink the tumor first (see below).

- Favorable histology: Treatment is usually surgery if it can be done, followed by radiation therapy over several days. This is followed by chemo with 3 drugs (actinomycin D, vincristine, and doxorubicin). If the tumor cells have certain chromosome changes, the drugs cyclophosphamide and etoposide may be given as well. Chemo is given for about 6 months.

- Anaplastic histology, with focal (only a little) anaplasia: Treatment starts with surgery if it can be done, followed by radiation therapy over several weeks. This is followed by chemo, usually with 3 drugs (actinomycin D, vincristine, and doxorubicin) for about 6 months.

- Anaplastic histology, with diffuse (widespread) anaplasia: Treatment starts with surgery if it can be done, followed by radiation therapy over several weeks. This is followed by chemo, usually with the drugs vincristine, doxorubicin, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, and carboplatin, along with mesna (a drug that helps protect the bladder from the effects of cyclophosphamide). Chemo lasts about 6 months.

In some instances the tumor may be very large or may have grown into nearby blood vessels or other structures so that it can’t be removed safely. In these children, a small biopsy sample is taken from the tumor to be sure that it’s a Wilms tumor and to determine its histology. Then chemo is started. Usually the tumor will shrink enough within several weeks so that surgery can be done. If not, then radiation therapy might be given as well. Chemo will be started again after surgery. If radiation was not given before surgery, it’s given after surgery.

Stage 4 Wilms tumor treatment

Stage 4 Wilms tumors have already spread to distant parts of the body at the time of diagnosis. As with stage 3 Wilms tumors, surgery to remove the tumor might be the first treatment, but it might need to be delayed until other treatments can shrink the tumor (see below).

- Favorable histology: Surgery to remove the tumor is the first treatment if it can be done, followed by radiation therapy. The entire abdomen will be treated if there is still some cancer left after surgery. If the cancer has spread to the lungs, low doses of radiation might also be given to that area. This is followed by chemo, usually with 3 drugs (actinomycin D, vincristine, and doxorubicin) for about 6 months. If the tumor cells have certain chromosome changes, the drugs cyclophosphamide and etoposide may be given as well.

- Anaplastic histology: Treatment might start with surgery if it can be done, followed by radiation therapy. The entire abdomen will be treated if there is still some cancer left after surgery. Low doses of radiation will also be given to the lungs if the cancer has spread there. This is followed by chemo with the drugs vincristine, doxorubicin, etoposide, cyclophosphamide, and carboplatin, along with mesna given for about 6 months. If the tumor cells have diffuse (widespread) anaplasia, some doctors might try the chemo drugs irinotecan and vincristine first instead (although this is not yet a commonly used treatment). The treatment would then be adjusted if the tumor shrinks in response to these drugs.

If the tumor is too large or has grown too much to be removed safely with surgery first, a small biopsy sample may be taken from the tumor to be sure that it’s a Wilms tumor and to determine its histology. Chemo and/or radiation therapy may then be used to shrink the tumor. Surgery might be an option at this point. This would be followed by more chemo and radiation therapy if it wasn’t given already.

For stage 4 cancers that have spread to the liver, surgery may be an option to remove any liver tumors that still remain after chemo and radiation therapy.

Stage 5 Wilms tumor treatment

Treatment for children with tumors in both kidneys is unique for each child, although it typically includes surgery, chemo, and radiation therapy at some point.

Biopsies (tissue samples) of tumors in both kidneys and of nearby lymph nodes may be taken first, although not all doctors feel this is needed because when both kidneys have tumors, the chance that they are Wilms tumors is very high.

Chemo is typically given first to try to shrink the tumors. The drugs used will depend on the extent and histology (if known) of the tumors. After about 6 weeks of chemo, surgery (partial nephrectomy) may be done to remove the tumors if enough normal kidney tissue can be left behind. If the tumors haven’t shrunk enough, treatment may include more chemo or radiation therapy for about another 6 weeks. Surgery (either partial or radical nephrectomy) may then be done. This is followed by more chemo, possibly along with radiation therapy if it hasn’t been given already.

If not enough functioning kidney tissue is left after surgery, a child may need dialysis, a procedure where a special machine filters waste products out of the blood several times a week. If there is no evidence of any cancer after a year or two, a donor kidney transplant may be done.

Recurrent Wilms tumor

The prognosis and treatment for children with Wilms tumor that recurs (comes back after treatment) depends on their prior treatment, the cancer’s histology (favorable or anaplastic), and where it recurs. The outlook is generally better for recurrent Wilms tumors with the following features:

- Favorable histology

- Initial diagnosis of stage 1 or 2

- Initial chemo with vincristine and actinomycin D only

- No previous radiation therapy

The usual treatment for these children is surgery to remove the recurrent cancer (if possible), radiation therapy (if not already given to the area), and chemo, often with drugs different from those used during first treatment.

Recurrent Wilms tumors that do not have the features above are much harder to treat. These children are usually treated with aggressive chemo, such as the ICE regimen (ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide) or others being studied in clinical trials. Very high-dose chemo followed by a stem cell transplant (sometimes called a bone marrow transplant) might also be an option in this situation, although this is still being studied.

What Happens After Treatment for Wilms Tumor?

During and after treatment for Wilms tumors, the main concerns for most families are the short- and long-term effects of the tumor and its treatment, and concerns about the tumor still being there or coming back.

It’s certainly normal to want to put the tumor and its treatment behind you, and get back to a life that doesn’t revolve around cancer. But it’s important to realize that follow-up care is a central part of treatment that offers your child the best chance for long-term recovery.

Follow-up exams and tests

Your child’s health care team will set up a follow-up schedule, which will include physical exams and imaging tests (such as chest x-rays, ultrasounds, and CT scans) to look for the growth or return of the tumor, or any problems related to treatment.

Since most children have had a kidney removed, blood and urine tests will be done to check how well the remaining kidney is working. If your child received the drug doxorubicin (Adriamycin) during chemotherapy, the doctor may also order tests to check the function of your child’s heart.

The recommended schedule for follow-up exams and tests depends on several factors, including:

- The initial stage and histology (favorable or anaplastic) of the tumor

- If the child has a genetic syndrome related to the tumor

- The type of treatment the child received

- Any problems that the child may have had during treatment

Doctor visits and tests will be more frequent at first (about every 6 to 12 weeks for the first couple of years), but the time between visits may be extended as time goes on.

During this time, it’s important to report any new symptoms to your child’s doctor right away, so that the cause can be found and treated, if needed. Your child’s doctor can give you an idea of what to watch for.

If the tumor does come back, or if it doesn’t respond to treatment, your child’s doctors will discuss the treatment options with you.

Children with bilateral Wilms tumors (tumors in both kidneys) or Denys-Drash syndrome will also need regular tests to look for possible early signs of kidney failure (including urine tests, blood pressure checks, and blood tests of kidney function).

Late and long-term effects of treatment

Because of major advances in treatment, most children treated for Wilms tumor are now surviving into adulthood. Doctors have learned that treatment can affect children’s health later in life, so watching for health effects as they get older has become more of a concern in recent years.

Just as the treatment of childhood cancer requires a very specialized approach, so does the care and follow-up after treatment. The earlier any problems can be recognized, the more likely it is they can be treated effectively. Young people treated for Wilms tumor are at risk, to some degree, for several possible late effects of their cancer treatment. It’s important to discuss what these possible effects might be with your child’s medical team so you know what to watch for and report to the doctor

The risk of late effects depends on a number of factors, such as the specific treatments the child had, the doses of treatment, and the age of the child when being treated. These late effects may include:

- Reduced kidney function

- Heart or lung problems after getting certain chemotherapy drugs or radiation therapy to the chest

- Slowed or delayed growth and development

- Changes in sexual development and ability to have children, especially in girls

- Increased risk of second cancers later in life (although these are rare)

There may be other possible complications from treatment as well. Your child’s doctors should discuss any possible problems with you.

Caring for Your Child

As much as parents long to have their child out of the hospital, they often feel unsure of whether they can provide appropriate care after their child comes home. The doctors, nurses, and home health services should provide all the information and support needed to help a parent care for a child between hospital visits.

Depending on the treatment regimen (and a child’s general health and the doctor’s recommendations), appropriate at-home care can vary. Treatment for most children with Wilms tumor is not as intensive as treatment for other cancers (except for more advanced stages) so most kids won’t have tremendous restrictions on them.

Most kids undergoing treatment for Wilms don’t have special nutritional requirements or need medication for low blood cell counts, as most other cancer patients do. However, parents must watch for signs of distress, like fever, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. A child with a high fever should see a doctor right away.

Once a child is finished with therapy, the care team will provide a schedule of follow-up tests. Chest X-rays or CT scans may be taken every several months. Stage and histology of the cancer will determine the ultrasound schedule. Blood work and a physical exam may be required to check for adverse effects of the treatment.

For kids who relapse (the cancer returns), prognosis and treatment depend on their prior therapy, the cancer’s histology, and how long it’s been since the last treatment. The longer it’s been, the better. There are few late recurrences of Wilms tumor, so remaining cancer-free for at least 2 years after treatment is generally a very good sign.

Coping and support

Here are some suggestions to help you guide your family through cancer treatment.

At the hospital

When your child has medical appointments or stays in the hospital:

- Bring a favorite toy or book to office or clinic visits, to keep your child occupied while waiting.

- Stay with your child during a test or treatment, if possible. Use words that he or she will understand to describe what will happen.

- Include play time in your child’s schedule. Major hospitals usually have a playroom for children undergoing treatment. Often playroom staff members are part of the treatment team, with training in child development, recreation, psychology or social work. If your child must remain in his or her room, a child life specialist or recreational therapist may be available to make a bedside visit.

- Ask for support from clinic or hospital staff members. Seek out organizations for parents of children with cancer. Parents who have already been through this can provide encouragement and hope, as well as practical advice. Ask your child’s doctor about local support groups.

At home

After leaving the hospital:

- Monitor your child’s energy level outside of the hospital. If he or she feels well enough, gently encourage participation in regular activities. At times your child will seem tired or listless, particularly after chemotherapy or radiation, so make time for enough rest, too.

- Keep a daily record of your child’s condition at home — body temperature, energy level, sleeping patterns, drugs administered and any side effects. Share this information with your child’s doctor.

- Plan a normal diet unless your child’s doctor suggests otherwise. Prepare favorite foods when possible. If your child is undergoing chemotherapy, his or her appetite may dwindle. Make sure fluid intake increases to counter the decrease in solid food intake.

- Encourage good oral hygiene for your child. A mouth rinse can be helpful for sores or areas that are bleeding. Use lip balm to soothe cracked lips. Ideally, your child should have necessary dental care before treatment begins. Afterward check with your child’s doctor before scheduling visits to the dentist.

- Check with the doctor before any vaccinations, because cancer treatment affects the immune system.

- Be prepared to talk with your other children about the illness. Tell them about changes they might see in their sibling, such as hair loss and flagging energy, and listen to their concerns.

- Wilms Tumor and Other Childhood Kidney Tumors Treatment (PDQ®)–Health Professional Version. https://www.cancer.gov/types/kidney/hp/wilms-treatment-pdq[↩][↩]

- Key Statistics for Wilms Tumors. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/wilms-tumor/about/key-statistics.html[↩][↩][↩]

- Fernandez C, Geller J, Ehrlich P, van den Heuvel-Eibrink M, Graf N, Mullen E, Hill D, Kalapurakal J, Dome J. Renal tumors. In: Blaney S, Helman LJ, Adamson PC, eds. Pizzo and Poplack’s Pediatric Oncology, 8 ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2021:673-92.[↩]

- Al-Hussain T, Ali A, Akhtar M. Wilms tumor: an update. Adv Anat Pathol. 2014 May;21(3):166-73. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000017[↩]

- Scott RH, Stiller CA, Walker L, Rahman N. Syndromes and constitutional chromosomal abnormalities associated with Wilms tumour. J Med Genet. 2006 Sep;43(9):705-15. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.041723[↩]

- Dumoucel, S., Gauthier-Villars, M., Stoppa-Lyonnet, D., Parisot, P., Brisse, H., Philippe-Chomette, P., Sarnacki, S., Boccon-Gibod, L., Rossignol, S., Baumann, C., Aerts, I., Bourdeaut, F., Doz, F., Orbach, D., Pacquement, H., Michon, J. and Schleiermacher, G. (2014), Malformations, genetic abnormalities, and wilms tumor. Pediatr Blood Cancer, 61: 140-144. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.24709[↩]

- Gracia Bouthelier R, Lapunzina P. Follow-up and risk of tumors in overgrowth syndromes. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2005 Dec;18 Suppl 1:1227-35. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2005.18.s1.1227[↩]

- Lapunzina, P. (2005), Risk of tumorigenesis in overgrowth syndromes: A comprehensive review. Am. J. Med. Genet., 137C: 53-71. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.c.30064[↩]

- SEER Cancer Statistics Review (CSR) 1975-2016. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2016/[↩]

- Norman Breslow, Andrew Olshan, J. Bruce Beckwith, Jami Moksness, Polly Feigl, Daniel Green, Ethnic Variation in the Incidence, Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Follow-up of Children With Wilms’ Tumor, JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Volume 86, Issue 1, 5 January 1994, Pages 49–51, https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/86.1.49[↩][↩]

- Sudour-Bonnange H, Coulomb-Lherminé A, Fantoni JC, Escande A, Brisse HJ, Thebaud E, Verschuur A. Standard of care for adult Wilms tumor? From adult urologist to pediatric oncologist. A retrospective review. Bull Cancer. 2021 Feb;108(2):177-186. doi: 10.1016/j.bulcan.2020.09.007[↩]

- Smith MA, Altekruse SF, Adamson PC, Reaman GH, Seibel NL. Declining childhood and adolescent cancer mortality. Cancer. 2014 Aug 15;120(16):2497-506. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28748[↩]

- Ehrlich P, Chi YY, Chintagumpala MM, Hoffer FA, Perlman EJ, Kalapurakal JA, Warwick A, Shamberger RC, Khanna G, Hamilton TE, Gow KW, Paulino AC, Gratias EJ, Mullen EA, Geller JI, Grundy PE, Fernandez CV, Ritchey ML, Dome JS. Results of the First Prospective Multi-institutional Treatment Study in Children With Bilateral Wilms Tumor (AREN0534): A Report From the Children’s Oncology Group. Ann Surg. 2017 Sep;266(3):470-478. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002356[↩]

- Treger TD, Chowdhury T, Pritchard-Jones K, Behjati S. The genetic changes of Wilms tumour. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2019 Apr;15(4):240-251. doi: 10.1038/s41581-019-0112-0[↩]