What is Wolff Parkinson White syndrome

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome also known as WPW syndrome, accessory atrioventricular pathways or preexcitation syndrome, is a heart condition that causes the heart to beat abnormally fast for periods of time 1.

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome is a relatively common condition, in large-scale population-based studies involving children and adult populations the general prevalence of WPW syndrome has been estimated to affect between one and three in every 1,000 people (0.1 to 0.3 %). A general estimate by experts suggests that about 65% of adolescents and 40% of individuals over 30 years with a WPW pattern on a resting ECG are asymptomatic. The incidence of patients with the WPW pattern progressing to arrhythmia (heart rhythm problem) is thought to be around 1% to 2% per year, and WPW syndrome prevalence peaks from age 20 to 24 2, 3. WPW syndrome is more common in men than women.

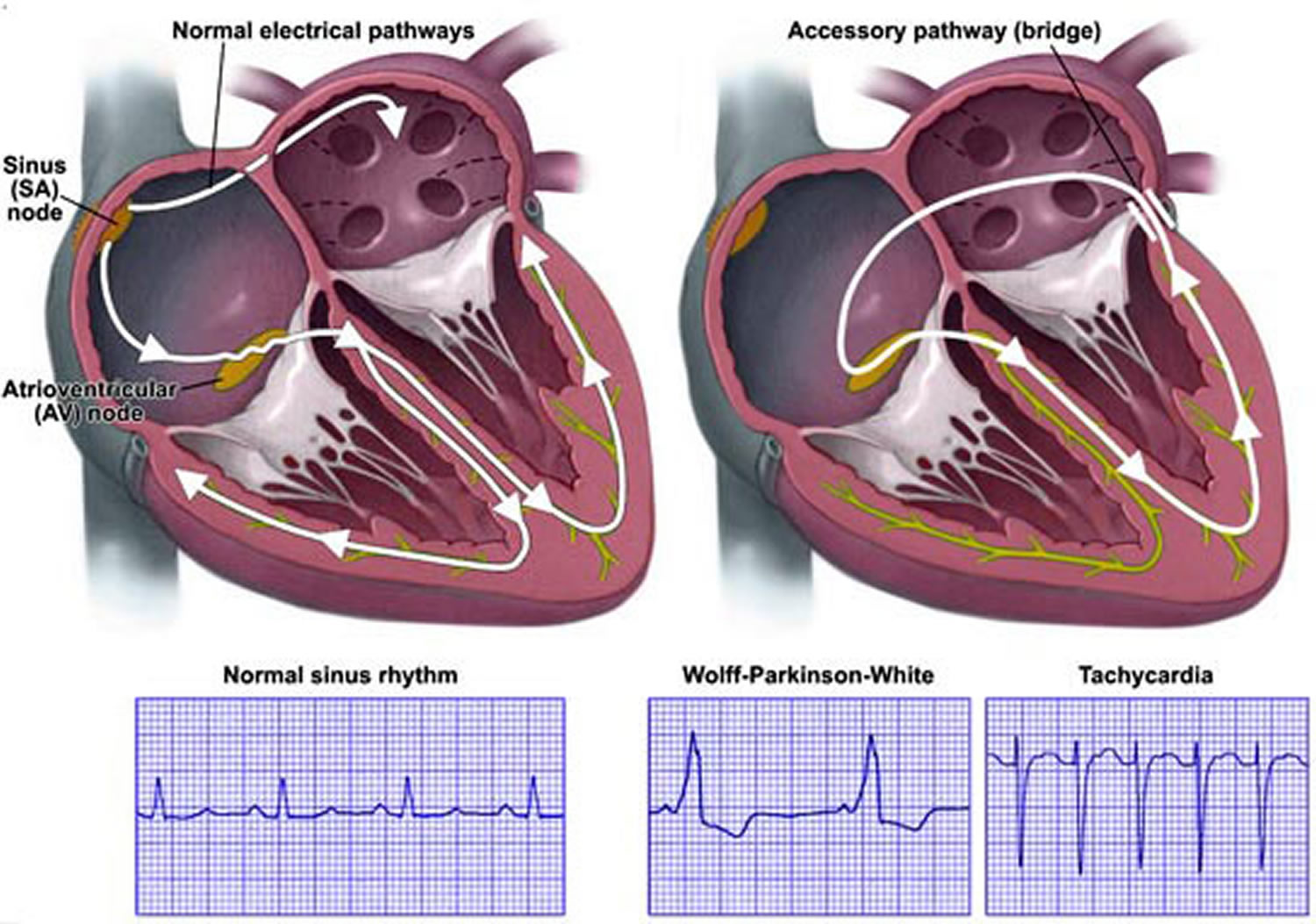

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome is caused by an abnormal electrical pathways between the atria and ventricles (called accessory pathways) causing the electrical signal to arrive at the ventricles too soon and to be transmitted back into the atria. These accessory pathways can cause electrical impulses to travel in both directions rather than one direction (normal direction from the atria into the ventricles). In Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, an extra electrical pathway between your heart’s upper chambers and lower chambers causes a rapid heartbeat. Some people with Wolff Parkinson White syndrome also have atrial fibrillation. Wolff Parkinson White syndrome causes the conduct of impulses to be faster than normal. Very fast heart rates may develop as the electrical signal ricochets between the atria and ventricles. Some people with WPW syndrome don’t have symptoms but they still have an increased risk for sudden cardiac death. The cause of sudden cardiac death in WPW syndrome is rapid conduction of atrial fibrillation (AF) to the ventricles via the accessory pathway, resulting in ventricular fibrillation (VF) 4, 1. The incidence of sudden cardiac death in WPW syndrome is approximately 1 in 100 symptomatic cases when followed for up to 15 years 4. Although relatively uncommon, sudden cardiac death may be the initial presentation in as many as 4.5% of cases 4.

Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome heart problem is present at birth (congenital), although symptoms may not develop until later in life. Many cases are diagnosed in otherwise healthy adults aged between 20 and 40.

The most common sign of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome is a heart rate greater than 100 beats a minute (tachycardia) 5. Episodes of a fast heart rate (tachycardia) can begin suddenly and may last a few seconds or several hours. Episodes can occur during exercise or while at rest. They most often appear for the first time in people in their teens or 20s.

Patients with WPW syndrome may also experience palpitations, dizziness, syncope (fainting), congestive heart failure or sudden cardiac death 6.

Sometimes the extra electrical connection won’t cause any symptoms and may only be picked up when an electrocardiogram (ECG) test is carried out for another reason. This condition is called Wolff-Parkinson-White pattern (WPW pattern). In these cases, further tests will be done to determine if treatment is required.

Doctors can detect WPW syndrome through a routine exam known as an electrocardiogram or ECG (see Figures 2 to 4). Electrodes placed on the chest will pick up the heart’s electrical activity and chart it on a graph. The electrocardiogram or ECG will show any irregularities.

The ECG features of WPW include a short PR interval of <0.12 seconds, slurring and slow rise of the initial QRS complex (delta wave), a widened QRS complex with a total duration >0.12 seconds, and an abnormal ventricular repolarization 1.

Treatment of WPW syndrome may include special actions, medications, a shock to the heart (cardioversion) or a catheter procedure to stop the irregular heart rhythm (arrhythmia).

Is Wolff Parkinson White syndrome serious?

It can be scary to be told that you have a problem with your heart, but Wolff Parkinson White syndrome usually isn’t serious.

Many people will have no symptoms or only experience occasional, mild episodes of their heart racing. With treatment, Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome can normally be completely cured.

Wolff Parkinson White syndrome can sometimes be life-threatening, particularly if it occurs alongside a type of irregular heartbeat called atrial fibrillation (see Figure 6). But this is rare and treatment can eliminate this risk.

Many things can cause a fast heartbeat. It’s important to get a prompt diagnosis and care. Sometimes a fast heartbeat or heart rate, isn’t a concern. For example, the heart rate may increase with exercise. If you feel like your heart is beating too fast, make an appointment to see your doctor in case it could be something serious.

Call your local emergency services number if you have any of the following symptoms for more than a few minutes:

- Sensation of a fast or pounding heartbeat

- Difficulty breathing

- Chest pain

- You have pain in your check, neck, jaw, arms or back for more than 15 minutes

- You have a fast heartbeat as well as other symptoms like feeling sick, being sick, feeling breathless or sweating

- You faint and someone can’t wake you up.

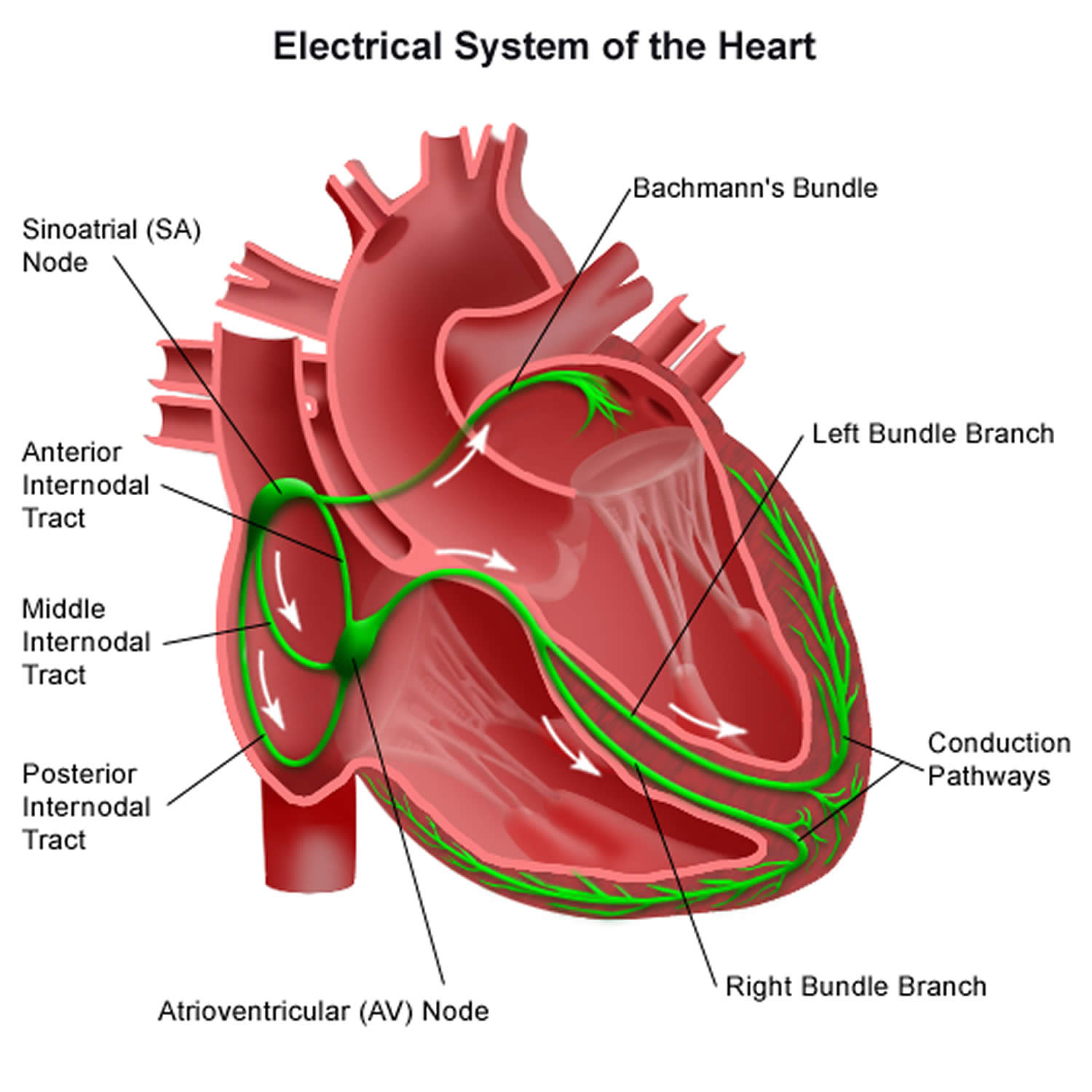

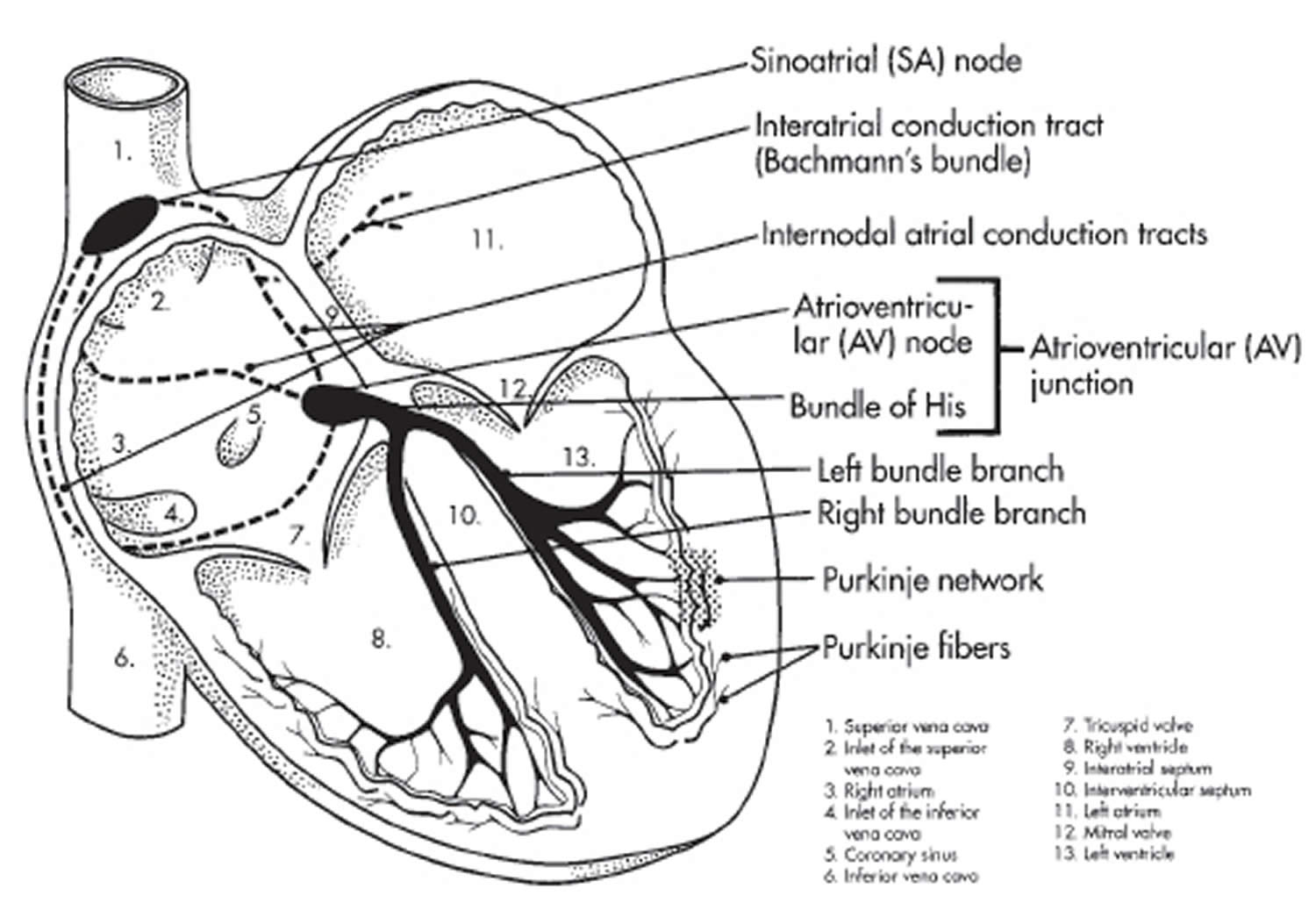

Normal heart electrical system

To understand WPW syndrome, it helps to understand the heart’s internal electrical system. The heart’s electrical system controls the rate and rhythm of the heartbeat.

The heart is made of four chambers — two upper chambers (atria) (one is called an atrium) and two lower chambers (ventricles).

Your heartbeat is the contraction of your heart to pump blood to your lungs and the rest of your body. Your heart’s electrical system determines how fast your heart beats. The contraction of the atria and ventricles makes a heartbeat. After your atria pump blood into the ventricles, the valves between the atria and ventricles close to prevent backflow. After your ventricles contract to pump blood away from the heart, the aortic and pulmonary valves close.

Your heart’s electrical system is made up of three main parts:

- The sinoatrial (SA) node, located in the right atrium of your heart

- The atrioventricular (AV) node, located on the interatrial septum close to the tricuspid valve

- The His-Purkinje system, located along the walls of your heart’s ventricles

Each beat of your heart is set in motion by an electrical signal from within your heart muscle. The signal is generated as the vena cavae fill your heart’s right atrium with blood from other parts of your body. The signal spreads across the cells of your heart’s right and left atria. In a normal, healthy heart, each beat begins with a signal from the natural pacemaker called the sinoatrial (SA) node — or sinus node — an area of specialized cells in the right atrium. This is why the sinoatrial (SA) node sometimes is called your heart’s natural pacemaker. Your pulse, or heart rate, is the number of signals the SA node produces per minute. In a healthy adult heart at rest, the SA node sends an electrical signal to begin a new heartbeat 60 to 100 times a minute. (This rate may be slower in very fit athletes.)

The sinoatrial (SA) node produces electrical impulses that normally start each heartbeat. This natural pacemaker produces the electrical impulses that trigger the normal heartbeat. From the sinus node, electrical impulses travel across the atria to the ventricles, causing them to contract and pump blood to your lungs and body.

From the sinoatrial (SA) node, electrical impulses travel across the atria, causing the atrial muscles to contract and pump blood into the ventricles.

The electrical impulses then arrive at a cluster of cells called the atrioventricular (AV) node — usually the only pathway for signals to travel from the atria to the ventricles.

The atrioventricular (AV) node slows down the electrical signal before sending it to the ventricles. This slight delay allows the ventricles to fill with blood.

The signal is released and moves along a pathway called the bundle of His, which is located in the walls of your heart’s ventricles. From the bundle of His, the signal fibers divide into left and right bundle branches through the Purkinje fibers. These fibers connect directly to the cells in the walls of your heart’s left and right ventricles.

The signal spreads across the cells of your ventricle walls, and both ventricles contract. However, this doesn’t happen at exactly the same moment.

The left ventricle contracts an instant before the right ventricle. This pushes blood through the pulmonary valve (for the right ventricle) to your lungs, and through the aortic valve (for the left ventricle) to the rest of your body.

As the signal passes, the walls of the ventricles relax and await the next signal.

This process continues over and over as the atria refill with blood and more electrical signals come from the SA node.

When electrical impulses reach the muscles of the ventricles, they contract, causing them to pump blood either to the lungs or to the rest of your body.

When anything disrupts this complex system, it can cause the heart to beat too fast (tachycardia), too slow (bradycardia) or with an irregular rhythm.

Your heart’s electrical system controls all the events that occur when your heart pumps blood. The electrical system also is called the cardiac conduction system. If you’ve ever seen the heart test called an EKG (electrocardiogram), you’ve seen a graphical picture of the heart’s electrical activity.

Figure 1. The heart’s electrical system

Abnormal electrical system in Wolff Parkinson White syndrome

In Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, an extra electrical pathway connects the atria and ventricles, allowing electrical impulses to bypass the AV node. When the electrical impulses use this detour through the heart, the ventricles are activated too early.

The extra electrical pathway can cause two major types of rhythm disturbances:

- Looped electrical impulses. In Wolff Parkinson White, the heart’s electrical impulses travel down either the normal or the extra pathway and up the other one, creating a complete electrical loop of signals. This condition (AV reentrant tachycardia) sends impulses to the ventricles at a very rapid rate. As a result, the ventricles pump very quickly, causing rapid heartbeat.

- Disorganized electrical impulses. If electrical impulses don’t begin correctly in the right atrium, they may travel across the atria in a disorganized way, causing atrial fibrillation. The disorganized signals and the extra pathway of Wolff Parkinson White also can cause the ventricles to beat faster. As a result, the ventricles don’t have time to fill with blood and don’t pump enough blood to the body.

Figure 2. Wolff Parkinson White syndrome

Note: In Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, an extra electrical pathway between your heart’s upper chambers and lower chambers causes a rapid heartbeat.

Note: In Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, an extra electrical pathway between your heart’s upper chambers and lower chambers causes a rapid heartbeat.Figure 3. Wolff Parkinson White syndrome ECG

Figure 4. Wolff Parkinson White syndrome ECG (Classic Wolff-Parkinson-White electrocardiogram with short PR, QRS >120 ms, and delta wave.)

Figure 5. WPW syndrome ECG

Note: 12-lead electrocardiogram from asymptomatic 7-year-old boy with Wolff-Parkinson-White pattern. Delta waves are positive in I and aVL; negative in II, III, and aVF; isoelectric in V1; and positive in rest of precordial leads. This predicts posteroseptal location for accessory pathway.

Figure 6. Preexcited atrial fribrillation

Wolff Parkinson White syndrome causes

When the heart beats, its muscular walls contract (tighten and squeeze) to force blood out and around the body. They then relax, allowing the heart to fill with blood again. This is controlled by electrical signals.

In Wolff Parkinson White syndrome, there’s an extra electrical connection called an accessory pathway (AP) in the heart between the top part (atria) of your heart and the bottom (ventricle), which allows electrical signals to bypass the usual route and form a short circuit. This electrical ‘short circuit’ means that signals travel round in a loop, causing episodes where the heart beats very fast.

The extra electrical connection called an accessory pathway (AP) is caused by a strand of heart muscle that grows while the unborn baby is developing in the womb (congenital heart defect) 7, 8, 9.

An accessory pathway is present from birth and WPW syndrome is most common in babies born with other types of heart defects (congenital heart disease such as Ebstein anomaly) 10. In Ebstein’s anomaly, the tricuspid valve is located lower than it should be, so the upper part of the right ventricle is part of the right atrium. This means that the right ventricle is too small and the right atrium is too large. However, Wolff Parkinson White syndrome is also seen in people who have structurally normal hearts.

It’s not clear exactly why this happens. It just seems to occur randomly in some babies, although rare cases have been found to run in families. Familial appearance of WPW syndrome displays an autosomal dominant inheritance. The PRKAG2 gene was identified as a possible susceptibility gene in WPW syndrome 11. PRKAG2 encodes the γ2 subunit of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which is an important regulator of cardiac metabolism 12.

Wolff Parkinson White is more common in males than in females.

Wolff Parkinson White syndrome complications

For many people, WPW syndrome doesn’t cause significant problems. But complications can occur, and it’s not always possible to know your risk of serious heart-related events. If the disorder is untreated, and particularly if you have other heart conditions, you may experience:

- Fainting spells

- Fast heartbeats

- Rarely, sudden cardiac death

Population studies suggest that sudden cardiac death is most often a result of ventricular fibrillation leading to cardiac arrest or with atrial fibrillation or circus movement tachycardia 7. The mechanism for deterioration to ventricular fibrillation leading to sudden cardiac death is an accessory pathway that is capable of rapid antegrade conduction that allows rapid transmission of atrial impulses to the ventricle 7. This can be exacerbated or initiated by the use of AV nodal blocking agents, and care should be taken to avoid these medications in the setting of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome on resting ECG with rapid atrial arrhythmias; atrial fibrillation and flutter are the most dangerous given their excessively rapid rates. Recurrent or prolonged tachyarrhythmias can predispose to heart failure. Hemodynamic instability during a tachyarrhythmia can initiate or exacerbate comorbid medical conditions. Patients that experience fainting (syncope) with acute arrhythmia are at risk for traumatic injuries 13, 2.

Wolff Parkinson White syndrome symptoms

People with Wolff Parkinson White syndrome may not get any symptoms, and the condition often goes undetected until later in life.

If you have Wolff Parkinson White syndrome, you’ll experience episodes where your heart suddenly starts racing, before stopping or slowing down abruptly. This rapid heart rate is called supraventricular tachycardia (SVT).

The most common sign of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome is a heart rate greater than 100 beats a minute. Episodes of a fast heart rate (tachycardia) can begin suddenly and may last a few seconds or several hours. Episodes can occur during exercise or while at rest. They most often appear for the first time in people in their teens or 20s.

Other signs and symptoms of WPW syndrome are related to the fast heart rate and underlying heart rhythm problem (arrhythmia). The most common arrhythmia seen with WPW syndrome is supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). Supraventricular tachycardia causes episodes of a fast, pounding heartbeat that begin and end abruptly. Some people with WPW syndrome also have a fast and chaotic heart rhythm problem called atrial fibrillation.

Common symptoms of Wolff Parkinson White syndrome include 14, 15:

- Sensation of rapid, fluttering or pounding heartbeats (palpitations)

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain

- Sweating

- Feeling anxious

- Finding physical activity exhausting

- Passing out or fainting (known as syncope)

- Fatigue

- Anxiety

Symptoms in more-serious cases

About 10 to 30 percent of people with WPW syndrome occasionally experience a type of irregular heartbeat known as atrial fibrillation. In these people WPW signs and symptoms may include:

- Chest pain

- Chest tightness

- Difficulty breathing

- Fainting

Symptoms in infants

Signs and symptoms in infants with WPW syndrome may include:

- Pale or faded skin color (pallor)

- Blue or gray coloring to the skin, lips and nails (cyanosis)

- Restlessness or irritability

- Rapid breathing

- Poor eating

WPW syndrome symptoms will affect people differently. An episode of a very fast heartbeat can begin suddenly and last for a few seconds, minutes or several hours. Rarely, they can last for days.

Episodes normally occur randomly, without any identifiable cause and occur during exercise or while at rest. They can sometimes be triggered by strenuous exercise, stress, caffeine or drinking alcohol for some people.

How often they occur varies from person to person. Some people may have episodes on a daily basis, while others may only experience them a few times a year.

- Call your local emergency services number for an ambulance if your symptoms are particularly severe or long-lasting.

If you’ve already been diagnosed with WPW syndrome and you experience an episode, first try the techniques you’ve been taught or take any medication you’ve been given (see below).

Over time, symptoms of Wolff Parkinson White may disappear in as many as 25 percent of people who experience them.

Wolff Parkinson White syndrome diagnosis

If your doctor thinks you might have Wolff Parkinson White syndrome after assessing your symptoms, they’ll probably recommend having an electrocardiogram (ECG) and will refer you to a cardiologist (heart specialist).

An ECG is a test that records your heart’s rhythm and electrical activity. Small discs called electrodes are stuck onto your arms, legs and chest and connected by wires to an ECG machine. The machine records the tiny electrical signals produced by your heart each time it beats.

If you have Wolff Parkinson White syndrome, the ECG will record an unusual pattern that isn’t usually present in people who don’t have the condition.

To confirm the diagnosis, you may be asked to wear a small portable ECG recorder (Holter monitor) so your heart rhythm can be recorded during an episode. A Holter monitor records your heart activity for 24 hours. An event recorder is a wearable ECG device is used to detect infrequent arrhythmias. You press a button when symptoms occur. An event recorder is typically worn for up to 30 days or until you have an arrhythmia or symptoms.

Electrophysiological testing. Thin, flexible tubes (catheters) tipped with electrodes are threaded through your blood vessels to various spots in your heart. The electrodes can precisely map the spread of electrical impulses during each heartbeat and identify an extra electrical pathway.

Wolff Parkinson White syndrome treatment

In many cases, episodes of abnormal heart activity associated with Wolff Parkinson White syndrome are harmless, don’t last long and settle down on their own without treatment.

You may therefore not need any treatment if your symptoms are mild or occur very occasionally, although you should still have regular check-ups so your heart can be monitored.

If your cardiologist recommends treatment, there are a number of options available. You can have treatment to either stop episodes when they occur, or prevent them occurring in the future.

Stopping an episode

There are three main techniques and treatments that can help stop episodes as they occur. These are:

- Vagal manoeuvers – techniques designed to stimulate the nerve that slows down the electrical signals in your heart. Types of vagal manoeuvres:

- Coughing. This can create pressure in your chest which can trigger your vagus nerve.

- Valsalva manoeuver. Breathe out through your mouth hard whist pinching your nose tightly as if you’re on the toilet. The pressure can set your heart off into its normal rhythm.

- Holding your knees against your chest.

- Ice or cold water. Cold showers, cold baths, ice packs on the face or putting your face in very cold water for a few seconds can help to lower your heart rate.

- Gag reflex. Causing yourself to lightly gag can get the vagus nerve working.

- Medication – an injection of medicine such as adenosine can be given in hospital if vagal manoeuvers don’t help. It can block the abnormal electrical signals in your heart. This will make your heart’s electrical messages travel through the normal path and set your heartbeat back to normal. You may also be given daily tablets to control the speed of the electrical messages being delivered to your heart.

- Cardioversion – a type of electric shock therapy that jolts the heart back into a normal rhythm. This may be carried out in hospital if the above treatments don’t work.

Preventing further episodes

Techniques and treatments that can help prevent episodes include:

- Lifestyle changes – if your episodes are triggered by things such as strenuous exercise, caffeine, other stimulants or alcohol, avoiding these may help. Your cardiologist can advise you about this.

- Medication – daily tablets of medication such as amiodarone can help prevent episodes by slowing down the electrical impulses in your heart.

- Radiofrequency catheter ablation – this procedure is commonly used nowadays to destroy the extra part of the heart causing the problems in the heart’s electrical system. Thin, flexible tubes (catheters) are threaded through blood vessels to your heart. Electrodes at the catheter tips are heated to destroy (ablate) the extra electrical pathway causing your condition. Radiofrequency ablation permanently corrects the heart-rhythm problems in most people with Wolff Parkinson White syndrome. It’s effective in around 95% of cases. Catheter ablation is very effective at preventing future episodes of Wolff Parkinson White syndrome (19 out of every 20 people treated will never have the problem again), but like all operations it carries a risk of complications. These include bruising and bleeding where the catheter was inserted. Any bruising will usually be small, but even if you have a large bruise it won’t require any treatment and will disappear within two weeks. There’s also a small risk (less than 1 in 100) of the heart’s normal electrical system being damaged. This is known as heart block, and if it happens you may need a permanent pacemaker to control your heart rhythm. You should discuss potential benefits and risks of catheter ablation with your surgeon (the electrophysiologist) before the procedure.

Wolff Parkinson White syndrome prognosis

Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome is a rare condition, and most patients with preexcitation on ECG will never have symptoms, associated arrhythmias (irregular heartbeats), or the most feared complication of sudden cardiac death 7. Two population studies put the rate of sudden cardiac death between 0.0002 to 0.0015 per patient-years for patients with WPW syndrome 7. Some risk factors place a patient at higher risk for sudden cardiac death, including male gender, age less than 35 years, history of atrial fibrillation or atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia, multiple accessory pathways, septal location of the accessory pathway, the ability for rapid anterograde conduction of the accessory pathway 2, 16, 17. Despite the low prevalence of WPW syndrome or the low incidence of serious complications, it remains a dangerous medical condition. The prognosis for patients with WPW syndrome has improved significantly as antiarrhythmic medications, and ablation techniques were developed over the last 80 years. For patients who have WPW syndrome, high-risk factors, or strong preference, radiofrequency catheter ablation can be curative and has high success rates with low rates of complications 18.

- Silva G, de Morais GP, Primo J, Sousa O, Pereira E, Ponte M, Simões L, Gama V. Aborted sudden cardiac death as first presentation of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Rev Port Cardiol. 2013 Apr;32(4):325-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.repc.2012.08.015[↩][↩][↩]

- Fitzsimmons PJ, McWhirter PD, Peterson DW, Kruyer WB. The natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in 228 military aviators: a long-term follow-up of 22 years. Am Heart J. 2001 Sep;142(3):530-6. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.117779[↩][↩][↩]

- KOBZA, R., TOGGWEILER, S., DILLIER, R., ABÄCHERLI, R., CUCULI, F., FREY, F., JAKOB SCHMID, J. and ERNE, P. (2011), Prevalence of Preexcitation in a Young Population of Male Swiss Conscripts. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology, 34: 949-953. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.2011.03085.x[↩]

- Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/159222-overview#a6[↩][↩][↩]

- Cain N, Irving C, Webber S, Beerman L, Arora G. Natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome diagnosed in childhood. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:961–965. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.05.035.[↩]

- Qiu M, Lv B, Lin W, Ma J, Dong H. Sudden cardiac death due to the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: A case report with genetic analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018 Dec;97(51):e13248. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013248[↩]

- Chhabra L, Goyal A, Benham MD. Wolff Parkinson White Syndrome. [Updated 2022 Aug 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554437[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Moorman A, Webb S, Brown NA, Lamers W, Anderson RH. Development of the heart: (1) formation of the cardiac chambers and arterial trunks. Heart. 2003 Jul;89(7):806-14. doi: 10.1136/heart.89.7.806[↩]

- Mirzoyev S, McLeod CJ, Asirvatham SJ. Embryology of the conduction system for the electrophysiologist. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2010 Aug 15;10(8):329-38[↩]

- Wever EF, Robles de Medina EO. Sudden death in patients without structural heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004 Apr 7;43(7):1137-44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2003.10.053[↩]

- Zhang LP, Hui B, Gao BR. High risk of sudden death associated with a PRKAG2-related familial Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. J Electrocardiol. 2011 Jul-Aug;44(4):483-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2010.02.009[↩]

- Hinson JT, Chopra A, Lowe A, Sheng CC, Gupta RM, Kuppusamy R, O’Sullivan J, Rowe G, Wakimoto H, Gorham J, Burke MA, Zhang K, Musunuru K, Gerszten RE, Wu SM, Chen CS, Seidman JG, Seidman CE. Integrative Analysis of PRKAG2 Cardiomyopathy iPS and Microtissue Models Identifies AMPK as a Regulator of Metabolism, Survival, and Fibrosis. Cell Rep. 2016 Dec 20;17(12):3292-3304. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.11.066. Erratum in: Cell Rep. 2017 Jun 13;19(11):2410[↩]

- MacRae CA, Ghaisas N, Kass S, Donnelly S, Basson CT, Watkins HC, Anan R, Thierfelder LH, McGarry K, Rowland E, et al. Familial Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome maps to a locus on chromosome 7q3. J Clin Invest. 1995 Sep;96(3):1216-20. doi: 10.1172/JCI118154[↩]

- Cain N, Irving C, Webber S, Beerman L, Arora G. Natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome diagnosed in childhood. Am J Cardiol. 2013;112:961–965. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.05.035[↩]

- Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. https://www.bhf.org.uk/informationsupport/conditions/wolff-parkinson-white-syndrome[↩]

- Munger TM, Packer DL, Hammill SC, Feldman BJ, Bailey KR, Ballard DJ, Holmes DR Jr, Gersh BJ. A population study of the natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1953-1989. Circulation. 1993 Mar;87(3):866-73. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.87.3.866[↩]

- Timmermans C, Smeets JL, Rodriguez LM, Vrouchos G, van den Dool A, Wellens HJ. Aborted sudden death in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1995 Sep 1;76(7):492-4. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80136-2[↩]

- Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES); Heart Rhythm Society (HRS); American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF); American Heart Association (AHA); American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP); Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS), Cohen MI, Triedman JK, Cannon BC, Davis AM, Drago F, Janousek J, Klein GJ, Law IH, Morady FJ, Paul T, Perry JC, Sanatani S, Tanel RE. PACES/HRS expert consensus statement on the management of the asymptomatic young patient with a Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW, ventricular preexcitation) electrocardiographic pattern: developed in partnership between the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of PACES, HRS, the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF), the American Heart Association (AHA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS). Heart Rhythm. 2012 Jun;9(6):1006-24. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.03.050[↩]