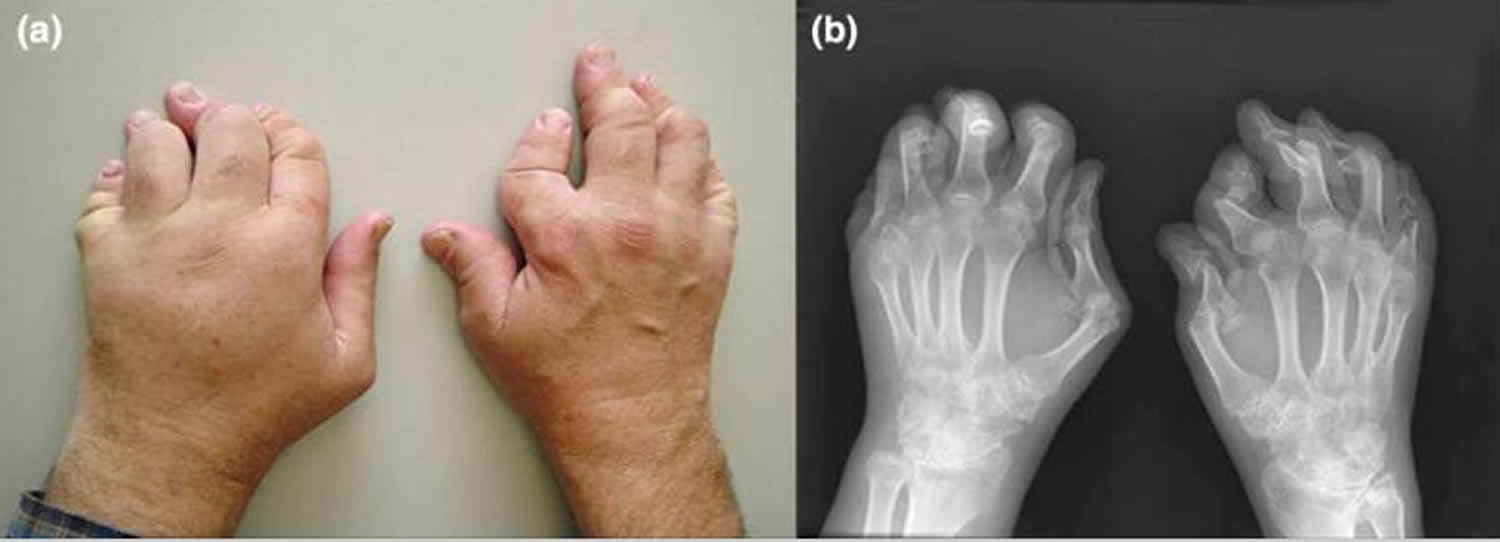

Arthritis mutilans

Arthritis mutilans also known as psoriatic arthritis mutilans, is the most severe form of psoriatic arthritis, arthritis mutilans affects only 5 percent of people who have psoriatic arthritis 1. Arthritis mutilans causes deformities in the small joints at the ends of the fingers and toes, and can destroy them almost completely (see Figure 1). One of the clinical manifestations of psoriatic arthritis mutilans is shortening of one or more digits due to severe osteolysis, a deformity called “opera glass finger” or “telescoping finger” 2. The radiographic findings of psoriatic arthritis mutilans is characterized by severe radiographic erosion with bony osteolysis and pencil-in-cup deformities in joints, often resulting in digital shortening and the ‘main en lorgnette’ (opera-glass hand) deformity 3. Radiographic features in psoriatic arthritis mutilans include bone resorption (41%), joint ankylosis (21%), pencil-in-cup changes (16%), total joint erosion (14%), and joint subluxation (7%) 4. Bone proliferation and arthrodesis may coexist with erosion in psoriatic arthritis and both forms of bone disease have been described in arthritis mutilans 5.

About 30 percent of people with psoriasis also develop a form of inflammatory arthritis called psoriatic arthritis. Like psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis is an autoimmune disease, meaning it occurs when the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks healthy tissue, in this case the joints and skin. The faulty immune response causes inflammation that triggers joint pain, stiffness and swelling. The inflammation can affect the entire body and may lead to permanent joint and tissue damage if it is not treated early and aggressively.

Most people with psoriatic arthritis have skin symptoms before joint symptoms. However, sometimes the joint pain and stiffness strikes first. In some cases, people get psoriatic arthritis without any skin changes.

The disease may lay dormant in the body until triggered by some outside influence, such as a common throat infection. Another theory suggesting that bacteria on the skin triggers the immune response that leads to joint inflammation has yet to be proven.

Types of psoriatic arthritis

There are five types of psoriatic arthritis:

- Symmetric psoriatic arthritis: This makes up about 50 percent of psoriatic arthritis cases. Symmetric means it affects joints on both sides of the body at the same time. This type of arthritis is similar to rheumatoid arthritis.

- Asymmetric psoriatic arthritis: Often mild, this type of psoriatic arthritis appears in 35 percent of people with the condition. It’s called asymmetric because it doesn’t appear in the same joints on both sides of the body.

- Distal psoriatic arthritis: This type causes inflammation and stiffness near the ends of the fingers and toes, along with changes in toenails and fingernails such as pitting, white spots and lifting from the nail bed.

- Spondylitis: Pain and stiffness in the spine and neck are hallmarks of this form of psoriatic arthritis.

- Arthritis mutilans

Figure 1. Arthritis mutilans

Footnote: A patient with arthritis mutilans with digital shortening. (a) Clinical photograph. (b) Radiograph of the hands.

[Source 1 ]Psoriatic arthritis mutilans causes

The cause of psoriatic arthritis is unknown. Experts believe some people may be predisposed to an autoimmune disease like psoriatic arthritis. In fact, studies show a stronger genetic or family link to this particular disease than other autoimmune rheumatic diseases. About 40 percent of people who are diagnosed with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis have family members affected by the disease.

Not everyone who has psoriasis develops psoriatic arthritis. Psoriasis is not infectious, but the disease might be triggered by a strep throat. In addition to infections, researchers believe psoriatic arthritis also can be triggered by extreme stress or an injury that makes the immune system go into overdrive in people who are genetically more likely to get the disease.

Psoriatic arthritis mutilans symptoms

Symptoms of psoriatic arthritis vary among different people. Many are common to other forms of arthritis, making the disease tricky to diagnose. Here’s a look at the most common symptoms – and the other conditions that share them.

Many people experience frequent periods of increased disease activity and symptoms, called flares, while others have only infrequent flares. This waxing and waning of symptoms is frequently seen with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), as well.

Painful, swollen joints

Psoriatic arthritis typically affects the ankle, knees, fingers, toes and lower back. Pain in the lower back is also a symptom of ankylosing spondylitis, a form of inflammatory arthritis that causes the vertebrae to fuse, or joint together. Also, the joint at the tip of the finger may swell, making it easy to confuse with gout, a form of inflammatory arthritis that typically affects only one joint.

Stiffness

Joints tend to be stiff either first thing in the morning or after a period of rest. However, people with osteoarthritis often have similar stiffness.

Sausage-like fingers or toes

Many people with psoriatic arthritis have dactylitis, a sausage-like swelling along the entire length of their fingers or toes. This symptom is one that helps differentiate psoriatic arthritis from rheumatoid arthritis (RA), in which the swelling is usually confined to a single joint.

Skin rashes and nail changes

Psoriatic arthritis occurs with psoriasis so skin symptoms include thick, red skin with flaky, silver-white scaly patches. Nails may become pitted or infected-looking, or even lift from the nail bed entirely. These symptoms are unique to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, actually helps doctors confirm a diagnosis.

Fatigue

People with psoriatic arthritis often experience general feelings of fatigue. This symptom is a common feature of rheumatoid arthritis.

Reduced range of motion

The inability to move joints and limbs as freely as before is a sign of psoriatic arthritis and most other forms of arthritis.

Eye problems

People with psoriatic arthritis may get inflammation of the eyes that can cause redness, irritation and disturbed vision (uveitis) or redness and pain in tissues surrounding the eyes (conjunctivitis, or “pink eye”).

Psoriatic arthritis enthesitis

People with psoriatic arthritis often develop enthesitis, or tenderness or pain where tendons or ligaments attach to bones. This commonly occurs at the heel (Achilles tendinitis) or the bottom of the foot (plantar fasciitis), but it can also occur in the elbow (tennis elbow). Each of these conditions could just as easily result from sports injuries or overuse as from psoriatic arthritis.

Other symptoms of psoriatic arthritis

Psoriatic arthritis is closely linked with inflammatory bowel disease, especially the form called Crohn’s disease. It causes diarrhea and other gastrointestinal problems The inflammation that causes psoriatic arthritis may also harm the lungs, causing a condition known as interstitial lung disease that leads to shortness of breath, coughing and fatigue. Chronic inflammation can damage blood vessels, increasing the risk for heart attacks and strokes. People with psoriatic arthritis often develop metabolic syndrome, a group of conditions that include obesity, high blood pressure and poor cholesterol levels. Other problems that can accompany psoriatic arthritis include depression, an increased risk for osteopenia (thinning bones) and osteoporosis, and a higher-than-average risk of developing gout.

Psoriatic arthritis mutilans diagnosis

Diagnosing psoriatic arthritis can be a tricky process because its symptoms frequently mimic those of other forms of inflammatory arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and gout. It can also be confused with osteoarthritis (OA), the most common form of arthritis.

For a proper diagnosis, the primary care doctor will likely provide a referral to a rheumatologist, a type of doctor who specializes in arthritis and musculoskeletal diseases. A diagnosis is based on many things, including a thorough medical history and the results of a physical examination and medical tests.

Medical History

Because certain conditions can be inherited, the doctor will ask questions about the health history of the patient and his or her relatives.

Additional information needed to help diagnose psoriatic arthritis includes:

- A description of the symptoms

- Details about when and how the pain or other symptoms began

- Location of the pain, stiffness or other symptoms

- How the symptoms affect the patient’s daily life

- Details about medical problems that could be causing these symptoms and a list of currently used medications

Physical exam

The rheumatologist will perform a physical exam, looking for swelling and inflammation of the joints. He’ll also check for signs of psoriasis on the skin or abnormalities on fingernails and toenails. Keep in mind that psoriasis isn’t always readily visible. It can hide on the scalp, behind the ears, in the belly button and in the groove between the buttocks.

Diagnostic tests

The doctor may order X-rays to detect changes to the bones or joints. Blood tests will be done to check for signs of inflammation. They include C-reactive protein and rheumatoid factor (RF). People with psoriatic arthritis are almost always rheumatoid factor-negative. If blood tests are positive for rheumatoid factor, the doctor should suspect rheumatoid arthritis (RA) first.

A blood test to measure the sedimentation or “sed” rate is often done. The higher the “sed rate,” the greater the level of inflammation in the body. The doctor may also test joint fluid to exclude gout or infectious arthritis.

Because psoriatic arthritis can be tricky to diagnose, people sometimes are initially told they have another form of arthritis only to find out later they have psoriatic arthritis.

Ruling out other conditions

The symptoms of psoriatic arthritis can mimic other conditions. Common misdiagnoses include osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and gout. Below are some tips to help avoid a psoriatic arthritis misdiagnosis.

- If a single joint becomes swollen and extremely painful almost overnight, it’s probably gout. Gout pain comes on rapidly and is intense.

- If there is little or no joint swelling, osteoarthritis is the most likely diagnosis. Osteoarthritis pain tends to be felt after activity.

- If joint pain affects the same joint on both sides of the body (is symmetrical), it could be RA. Joint pain in psoriatic arthritis is usually asymmetrical, meaning it’s felt on one side of the body. For example, if one knee is affected, the other likely is not.

If joint pain is worse for more than a few minutes in the morning, or after inactivity, consider psoriatic arthritis or rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

If swelling involves the full length of the fingers or toes, think psoriatic arthritis. This condition is called dactylitis, or “sausage fingers.”

If there are psoriasis symptoms and nail pitting first, followed by joint pain, psoriatic arthritis is likely the culprit, particularly if there is joint swelling. A person can have psoriasis and a form of arthritis that isn’t psoriatic arthritis.

Psoriatic arthritis mutilans treatment

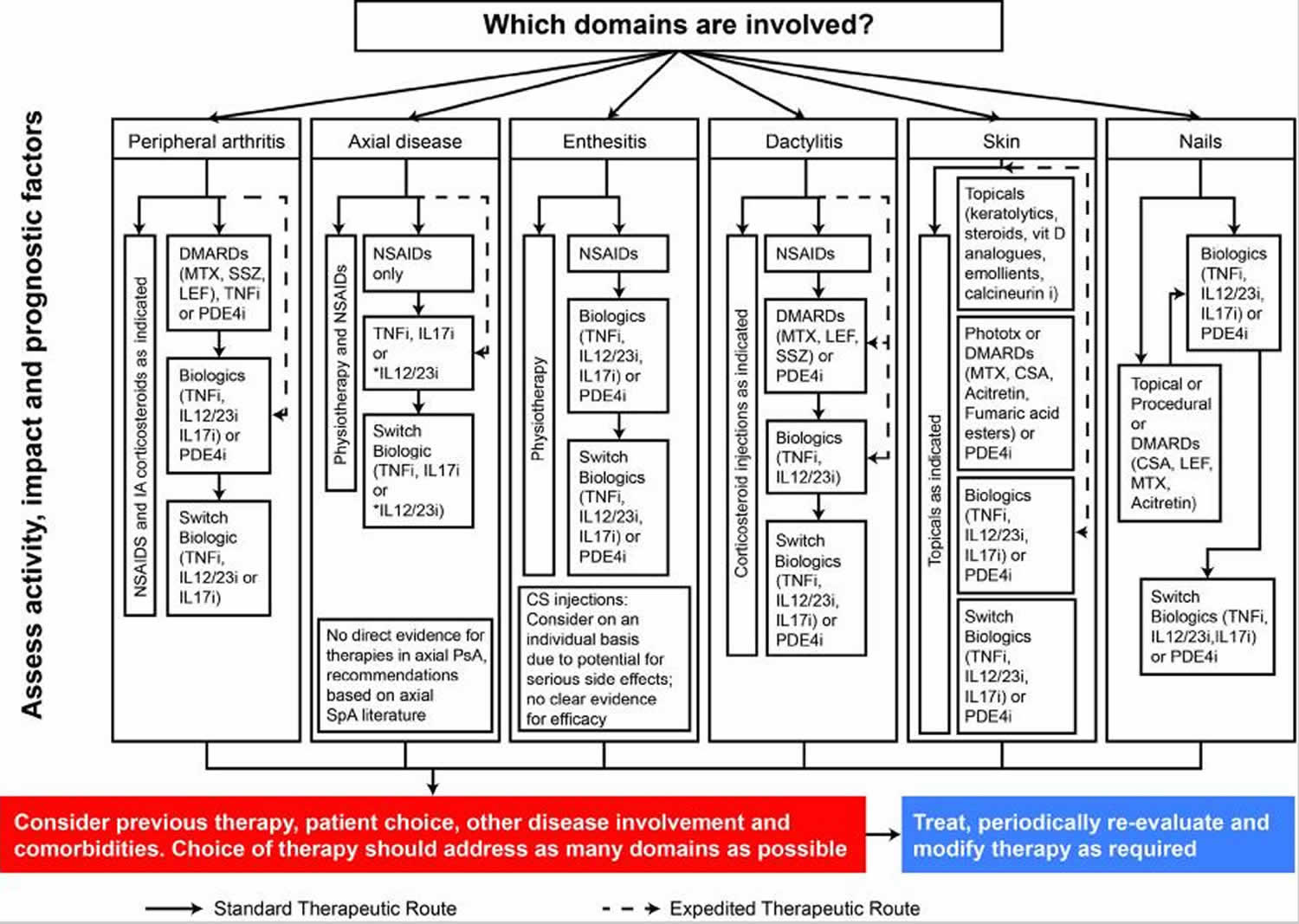

Treatment should be guided by disease severity, degree of joint damage, the extent of extra-articular disease, patient preference, and other co-morbidities. In 2016, the Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis 6 and the European League Against Rheumatism 7 both issued updated treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Given the breadth of available treatments for psoriatic arthritis and the significant heterogeneity in disease presentation, current guidelines provide treatment recommendations specific to each psoriatic arthritis domain (Figure 1) 6. Available treatments often vary in consistency and response across psoriatic arthritis domains.

Figure 1. Treatment schema for active psoriatic arthritis

[Source 8 ]Medications for psoriatic arthritis

- NSAIDs. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are usually taken by mouth, although some can be applied directly to the skin. These medicines reduce inflammation along with pain and swelling. Among the most well-known over-the-counter (OTC) NSAIDs are ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin) and naproxen sodium (Aleve), although there are many others. More than a dozen prescription NSAIDs also are available. The most notable risks of NSAIDs are an increased risk of heart attack and stroke, along with stomach irritation and bleeding that could become severe.

- Corticosteroids. These drugs are designed to mimic the anti-inflammatory hormone cortisol, which is normally made by the body’s adrenal glands. Corticosteroids taken by mouth, such as prednisone, can help reduce inflammation, but long-term use can lead to side effects such as facial swelling, weight gain, osteoporosis and more. Directly injecting corticosteroids into affected joints can provide temporary inflammation relief.

- Topical treatments. Topical medicines are applied directly to the skin to treat scaly, itchy rashes due to psoriasis. Available in creams, gels, lotions, shampoos, sprays or ointments, these drugs are available OTC (over-the-counter) and by prescription. OTC ones include salicylic acid, which helps lift and peel scales, and coal tar, which may slow rapid cell growth of scales and ease itching and inflammation. Prescription topicals contain corticosteroids and/or vitamin derivatives. Common prescription ones include calcitriol, a naturally occurring form of vitamin D3; calcipotriene, a synthetic form of vitamin D3; calcipotriene combined with the corticosteroid betamethasone dipropionate; tazarotene (a vitamin-A derivative); and anthralin, a synthetic form of chrysarobin, a substance derived from the South American araroba tree.

- DMARDs. Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) are a varied group of medications that suppress inflammation-causing chemicals to prevent joint damage and reduce symptoms. Most are taken by mouth. According to the American College of Rheumatology, DMARDs most commonly prescribed for psoriatic arthritis are methotrexate, sulfasalazine, cyclosporine and leflunomide. Azathioprine may also be prescribed. Apremilast is a newer DMARD approved in 2014. It works by blocking an enzyme called phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4), which is linked to inflammation. Studies have shown it reduces the number of tender and swollen joints.

- Biologics. Technically a subset of DMARDs, biologics are complex drugs that stop inflammation at the cellular level. They are usually given by injection or infusion. Three types of biologics are approved to treat psoriatic arthritis. They include:

- Anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) drugs that block a specific protein produced by immune cells that signals other cells to start the inflammatory process. These include etanercept, adalimumab, golimumab, infliximab and certolizumab.

- Selective co-stimulation moderators that interfere with the activation of white blood cells called T cells, preventing immune system reactions that result in inflammation. The only drug in this class is abatacept.

- IL-inhibitors that block pro-inflammatory proteins called interleukins. The drug ustekinumab specifically blocks IL-12 and -23.

While biologics can be very effective, they suppress the immune system and raise the risk of infection.

Tumor Necrosis Factor Inhibitors

TNF inhibitors are currently a cornerstone of biologic treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis 6, largely due to their established history as safe and effective treatments for both rheumatic and psoriatic disease 9. However, TNF is an upstream modulator of psoriatic arthritis pathogenesis, and targeting this cytokine can have relatively non-specific effects on psoriatic arthritis disease features, such as osteoclastogenesis and synovial inflammation 10. As such, some patients with psoriatic arthritis fail to respond to TNF inhibitors. Additionally, among individuals who do respond to initial treatment, efficacy can wane over time, resulting in failure to achieve lasting remission 11.

Interleukin-12/23 Inhibitor

Interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23 are important cytokines in the pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis. Upregulation of IL-12 promotes inflammation and activation of natural killer cells, and upregulation of IL-23 stimulates processes related to bone erosion and osteoclastogenesis 12. The IL-12/23 antagonist ustekinumab is approved for the treatment of active psoriatic arthritis based on results from clinical trials showing that treatment with ustekinumab significantly reduces radiographic progression of joint damage and improves signs and symptoms of enthesitis, dactylitis, skin disease, and nail dystrophy 13. Ustekinumab also improves skin and joint symptoms in patients with psoriatic arthritis who failed to respond to anti-TNF therapies 14.

IL-17A Inhibitors

Upregulation of IL-17A promotes angiogenesis, osteoclastogenesis, and fibrogenesis, which contribute to chronic inflammatory and bone changes that are hallmarks of psoriatic arthritis pathogenesis 15. There are two IL-17A inhibitors, secukinumab and ixekizumab, approved for the treatment of active psoriatic arthritis based on results from pivotal randomized controlled trials showing efficacy across peripheral arthritis, dactylitis, enthesitis, skin, and nail psoriatic arthritis domains. Additionally, secukinumab 150 mg was recently approved for the treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis 16 based on results of the MEASURE 1 and MEASURE 2 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trials 17. In both of these trials, secukinumab 150 mg provided ASAS20 response rates of 61% at week 16 18.

Apremilast

Apremilast is an orally administered small-molecule inhibitor of phosphodiesterase-4, which acts to degrade cyclic adenosine monophosphate, thereby downregulating production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-12, and IL-23 19. Twice-daily treatment with apremilast demonstrated efficacy compared with placebo for treatment of the peripheral arthritis, dactylitis, enthesitis, and skin domains of psoriatic arthritis in the large-scale PALACE clinical studies 20, and efficacy against nail disease was observed in the ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2 trials in patients with psoriasis 21. Axial disease was not evaluated as part of apremilast phase 3 programs.

Abatacept

Abatacept is a fusion protein construct that inhibits T cell activation by modulating CD28 co-stimulation associated with upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines 19. Abatacept is approved for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis, as well as psoriatic arthritis. In the phase 3 ASTRAEA study, abatacept demonstrated significant efficacy compared with placebo for peripheral arthritis; however, numerical improvements in dactylitis, enthesitis, and skin domains did not reach statistical significance, and nail disease was not assessed 22. Abatacept did not appear to demonstrate significant efficacy in axial disease in patients with ankylosing spondylitis 23.

Tofacitinib

Tofacitinib is an oral Janus kinase inhibitor that preferentially targets JAK3 and JAK1, blocking signaling pathways for several inflammatory cytokines 19. Tofacitinib is approved for the treatment of adults with moderately to severely active rheumatoid arthritis and active psoriatic arthritis in adults with inadequate response or intolerance to methotrexate or other non-biologic DMARDs. In the OPAL Beyond trial, tofacitinib was associated with improvements in peripheral arthritis and nail disease, but numerical improvements in dactylitis and enthesitis were not tested for statistical significance; the 10-mg dose but not the 5-mg dose was associated with significantly higher achievement of skin clearance (PASI75) compared with placebo 24. Results of a recently published phase 2 study of tofacitinib in patients with ankylosing spondylitis suggest it may improve axial symptoms of psoriatic arthritis 25.

Light therapy

Another option for treating psoriasis is phototherapy, or light therapy. In light therapy, the skin is regularly exposed to ultraviolet light. For safety reasons, this is done under medical supervision.

References- Tan YM, Østergaard M, Doyle A, et al. MRI bone oedema scores are higher in the arthritis mutilans form of psoriatic arthritis and correlate with high radiographic scores for joint damage. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11(1):R2. doi:10.1186/ar2586 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2688232

- Mochizuki T, Ikari K, Okazaki K. Delayed Diagnosis of Psoriatic Arthritis Mutilans due to Arthritis Prior to Skin Lesion. Case Rep Rheumatol. 2018;2018:4216938. Published 2018 Nov 4. doi:10.1155/2018/4216938 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6247716

- Eisenstadt HB, Eggers GW. Arthritis mutilans. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1955;37-A:337–346.

- Haddad A., Johnson S. R., Somaily M., et al. Psoriatic arthritis mutilans: clinical and radiographic criteria. A systematic review. Journal of Rheumatology. 2015;42(8):1432–1438. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141545

- O’Neill TW, Evison G, Bhalla AK. Pseudoarthroplastic’ hand in arthritis mutilans. Br J Rheumatol. 1992;31:559–560. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/31.8.559

- Coates LC, Kavanaugh A, Mease PJ, et al. Group for research and assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1060–1071.

- Gossec L, Smolen JS, Ramiro S, et al. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2015 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:499–510. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208337

- Giannelli A. A Review for Physician Assistants and Nurse Practitioners on the Considerations for Diagnosing and Treating Psoriatic Arthritis. Rheumatol Ther. 2019;6(1):5–21. doi:10.1007/s40744-018-0133-3

- Mease P. A short history of biological therapy for psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2015;33:S104–S108.

- Addimanda O, Possemato N, Caruso A, Pipitone N, Salvarani C. The role of tumor necrosis factor-α blockers in psoriatic disease. Therapeutic options in psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol Suppl. 2015;93:73–78. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.150642

- Garrido-Cumbrera M, Hillmann O, Mahapatra R, et al. Improving the management of psoriatic arthritis and axial spondyloarthritis: roundtable discussions with healthcare professionals and patients. Rheumatol Ther. 2017;4:219–231. doi: 10.1007/s40744-017-0066-2.

- Marinoni B, Ceribelli A, Massarotti MS, Selmi C. The Th17 axis in psoriatic disease: pathogenetic and therapeutic implications. Auto Immun Highlights. 2014;5:9–19. doi: 10.1007/s13317-013-0057-4.

- Kavanaugh A, Ritchlin C, Rahman P, et al. Ustekinumab, an anti-IL-12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, inhibits radiographic progression in patients with active psoriatic arthritis: results of an integrated analysis of radiographic data from the phase 3, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled PSUMMIT-1 and PSUMMIT-2 trials. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1000–1006. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204741

- Ritchlin C, Rahman P, Kavanaugh A, et al. Efficacy and safety of the anti-IL-12/23 p40 monoclonal antibody, ustekinumab, in patients with active psoriatic arthritis despite conventional non-biological and biological anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy: 6-month and 1-year results of the phase 3, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised PSUMMIT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:990–999. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204655

- de Vlam K, Gottlieb AB, Mease PJ. Current concepts in psoriatic arthritis: pathogenesis and management. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:627–634. doi: 10.2340/00015555-1833

- Cosentyx (secukinumab) [prescribing information]. Novartis, East Hanover. 2018.

- Braun J, Baraliakos X, Deodhar A, et al. Effect of secukinumab on clinical and radiographic outcomes in ankylosing spondylitis: 2-year results from the randomised phase III MEASURE 1 study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1070–1077. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209730

- Baeten D, Sieper J, Braun J, et al. Secukinumab, an interleukin-17A inhibitor, in ankylosing spondylitis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2534–2548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1505066

- Kang EJ, Kavanaugh A. Psoriatic arthritis: latest treatments and their place in therapy. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2015;6:194–203. doi: 10.1177/2040622315582354

- Edwards CJ, Blanco FJ, Crowley J, et al. Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, in patients with psoriatic arthritis and current skin involvement: a phase III, randomised, controlled trial (PALACE 3) Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:1065–1073. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-207963

- Rich P, Gooderham M, Bachelez H, et al. Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, in patients with difficult-to-treat nail and scalp psoriasis: results of 2 phase III randomized, controlled trials (ESTEEM 1 and ESTEEM 2) J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.001

- Mease PJ, Gottlieb AB, van der Heijde D, et al. Efficacy and safety of abatacept, a T-cell modulator, in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1550–1558. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210724

- Song IH, Heldmann F, Rudwaleit M, et al. Treatment of active ankylosing spondylitis with abatacept: an open-label, 24-week pilot study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1108–1110. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.145946

- Gladman D, Rigby W, Azevedo VF, et al. Tofacitinib for psoriatic arthritis in patients with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1525–1536. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1615977

- van der Heijde D, Deodhar A, Wei JC, et al. Tofacitinib in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: a phase II, 16-week, randomised, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1340–1347. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210322