Streptococcus agalactiae

Streptococcus agalactiae is a group B Streptococcus, is an encapsulated, opportunistic Gram-positive bacterium that causes illness in people of all ages such as neonatal invasive infections, including neonatal septicemia, pneumonia, meningitis, and orthopedic device infections 1. Also known as GBS (group B Streptococcus), Streptococcus agalactiae bacterium is a common cause of severe infections in newborns during the first week of life. Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) is a major cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality worldwide 2. More recently, experts recognized the increasing impact invasive group B Streptococcus disease has on adults.

Approximately 30,800 cases of invasive Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease occur annually in the United States in all age groups 3. This number includes invasive disease that manifests most commonly as bloodstream infections. In newborns, approximately 7,600 cases occurred before widespread adoption of prevention guidelines. The rate of early-onset infection decreased from 1.7 cases per 1,000 live births (1993) to 0.22 cases per 1,000 live births (2016). Racial disparities in disease persist with the incidence higher among African Americans for all age groups.

Streptococcus agalactiae are currently divided into ten serotypes based on type-specific capsular antigens and are designated as Ia, Ib, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, and IX. There are multiple methods to perform group B Streptococcus serotyping:

- The Lancefield precipitation test – considered the standard method for group B Streptococcus serotype determination

- Latex agglutination method – serotypes group B Streptococcus isolates phenotypically; several kits are commercially available

- Real-time PCR 4

- Conventional PCR – a recommended and validated method 5

- Whole-genome sequencing 6

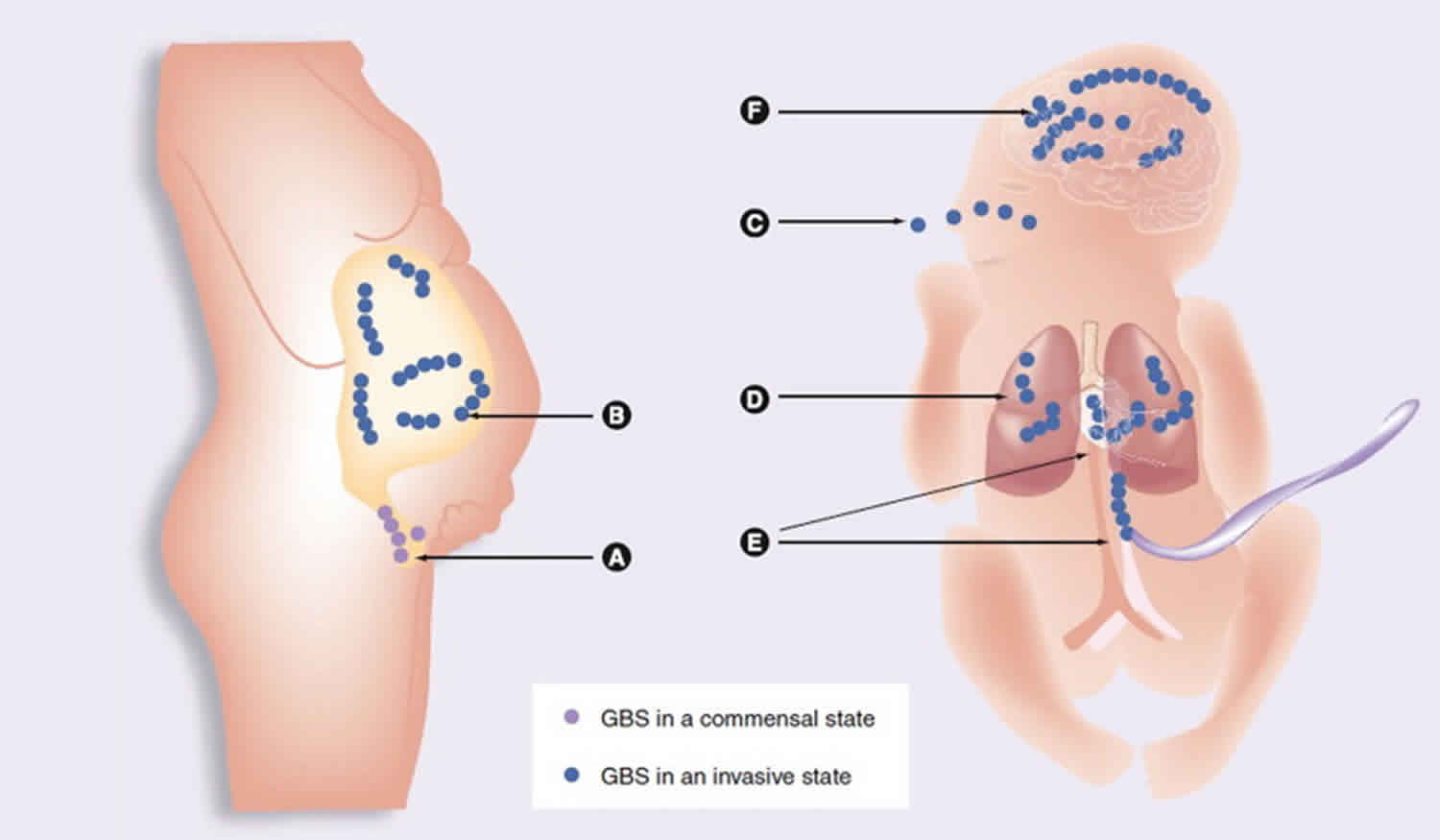

Epidemiological investigations in the United States and Europe show that serotypes Ia, Ib, III, and V account for 85–90% of all clinical isolates 7. Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) is found in the intestine and urogenital tracts of adult women and these women’s newborn babies may develop infection during exposure to the bacterium before birth or during the neonatal period. In the neonatal period, Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) can first be localized in the human vaginal epithelial cells, where it specifically attaches to molecules such as fibrinogen (FBG), fibronectin (Fn), and laminin (Lm), largely abundant in the extracellular matrix (ECM) and basement membranes 1. Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) can then infiltrate the uterine compartment of pregnant mothers where newborn aspirate Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) in utero or at birth 8. From there bacteria move toward the neonatal lung and gain access to the blood stream of the neonate with consequent bacteremia and sepsis syndrome. Finally, Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) invades multiple neonatal organs and penetrates the blood–brain barrier (BBB) eventually causing meningitis 8. Upon invasion and penetration into deep tissues, Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) are opsonized by antibodies and the complement system and ingested and killed by host phagocytic cells (neutrophils and macrophages) 9. To be successful, Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]), at each stage of this complex infective process, require the coordinate production and involvement of several factors. To mediate adherence to extracellular matrix and host cell surface, Streptococcus agalactiae expresses several surface-associated protein families including sets of cell wall-anchored proteins and lipoproteins and a myriad of secreted proteins that can re-bind to the bacterial cell surface. Typical examples of Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) adhesins are the cell wall-anchored FBG-binding protein A (FbsA) 10 and the secreted Lm-binding protein Lmb 11. Additional structures involved in adhesion are pili, long filamentous structures extending from the surface made up of the covalent polymerization of pilin subunits 12. Other cell wall-anchored and secreted proteins promote invasion of host epithelial cells. For example, alpha C protein, a cell wall-anchored protein 13, and FbsB, a secreted FBG-binding protein 14, both enhance internalization of Streptococcus agalactiae into epithelial cells. Translocation through placental, epithelial or endothelial barriers is facilitated by specific virulence determinants such as the pore-forming toxin known as β-hemolysin/cytolysin 15 and surface protein plasminogen-binding surface protein (PbsP), which captures plasminogen (PLG) 16. Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) expresses several cell wall-anchored proteins such as Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) immunogenic bacterial adhesion protein (BibA) 17 and the secreted protein complement inhibitory protein 18 with functions in avoidance of the host immune defense system. Finally, an additional factor targeting the innate immune system includes an extracellular DNA nuclease named NucA which degrades the DNA matrix comprising the neutrophil extracellular traps 19.

Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) key points

- In the United States of America, Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) is known to be the most common infectious cause of morbidity and mortality in neonates 20.

- Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis is only effective in the prevention of early-onset Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) infection 20.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends universal screening with Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) rectovaginal culture between 35 to 37 weeks in each pregnancy 20.

- Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended with positive Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) rectovaginal culture, Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) bacteriuria at any time during the pregnancy, or a history of delivery of infant affected by early onset Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) infection 20.

- If Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) status is unknown, antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended during preterm labor and delivery (less than 37 weeks), in the presence of maternal fever during labor, or with prolonged rupture of membranes (greater than 18 hours) 20.

- Intravenous Penicillin G is the antibiotic of choice for intrapartum prophylaxis 21.

- Additional options for antibiotic prophylaxis are ampicillin, cefazolin, clindamycin, or vancomycin 21.

Streptococcus agalactiae causes

Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) commonly live in people’s gastrointestinal and genital tracts. The gastrointestinal tract is the part of the body that digests food and includes the stomach and intestines. The genital tract is the part of the body involved in reproduction and includes the vagina in women. Most of the time the bacteria are not harmful and do not make people feel sick or have any symptoms. Sometimes the bacteria invade the body and cause certain infections, which are known as GBS disease.

Streptococcus agalactiae infection

Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) bacteria can cause many types of infections:

- Bacteremia (bloodstream infection) and sepsis (the body’s extreme response to an infection)

- Bone and joint infections

- Meningitis (infection of the tissue covering the brain and spinal cord)

- Pneumonia (lung infection)

- Skin and soft-tissue infections

Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) most commonly causes bacteremia, sepsis, pneumonia, and meningitis in newborns. It is very uncommon for Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) to cause meningitis in adults.

In neonates two syndromes exist for Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease:

- Early-onset (<7 days old)

- Late-onset (7-90 days old)

Both can manifest as bacteremia, sepsis, pneumonia, and meningitis. In adults, severe infections can manifest as bacteremia (including sepsis) and soft tissue infections. Pregnancy-related infections include:

- Bloodstream infections (including sepsis)

- Amnionitis

- Urinary tract infection

- Stillbirth

Streptococcus agalactiae (group B Streptococcus [GBS]), is an opportunistic Gram-positive human pathogen, is a major causative agent of pneumonia, sepsis, and meningitis in neonates and a serious cause of disease in parturient women and immunocompromised and elderly people 22. Streptococcus agalactiae [group B Streptococcus (GBS)] is also a frequent cause of bone and joint infections 23 and infections associated with orthopedic medical devices 24.

Streptococcus agalactiae (group B Streptococcus [GBS]) is the most common cause of neonatal sepsis in high-income countries 25. Disease risk is highest during the first 3 months of life and declines substantially thereafter. Early-onset disease (day 0–6) is the result of vertical transmission from a colonized mother during or just before delivery 26. Late-onset disease (day 7–89) can be acquired from the mother or from environmental sources 27. Case fatality from both early-onset and late-onset disease is high, even with antibiotic therapy 28. Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) is also an important cause of preterm delivery, antepartum and intrapartum stillbirth, and puerperal sepsis 29. Prevention of early-onset Streptococcus agalactiae (group B Streptococcus [GBS]) has become a realistic option, through the use of intrapartum antibiotics given to pregnant women with risk factors or known carriage of the bacteria (intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis) 30. This prophylaxis has been implemented in most high-income countries since the late 1990s, but has been difficult to implement in many low-income countries and middle-income countries 25. Several group B streptococcus vaccines are also at various stages of testing and could allow prevention of both early-onset disease and late-onset disease 31. However, many challenges exist to obtaining accurate estimates of disease burden, especially for low-income and middle-income countries, including difficulties with obtaining specimens and poor laboratory capacity for diagnosis of Streptococcus agalactiae (group B Streptococcus [GBS]).

Streptococcus agalactiae infection in babies

Among babies, there are 2 main types of Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease:

- Early-onset — occurs during the first week of life.

- Late-onset — occurs from the first week through three months of life.

In the United States, Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) bacteria are a leading cause of meningitis and bloodstream infections in a newborn’s first three months of life.

Early-onset disease used to be the most common type of Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease in babies. Today, because of effective early-onset disease prevention, early- and late-onset disease occur at similarly low rates.

In the United States on average each year:

- About 900 babies get early-onset Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease.

- About 1,200 babies get late-onset Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease.

Newborns are at increased risk for Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease if their mother tests positive for the bacteria during pregnancy.

- 2 to 3 in every 50 babies (4 to 6%) who develop Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease will die.

Streptococcus agalactiae infection in pregnant women

About 1 in 4 pregnant women carry Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) bacteria in their body.

Doctors should test pregnant woman for Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) bacteria when they are 36 through 37 weeks pregnant.

Giving pregnant women antibiotics through the vein (IV) during labor can prevent most early-onset Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease in newborns.

- A pregnant woman who tests positive for Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) bacteria and gets antibiotics during labor has only a 1 in 4,000 chance of delivering a baby who will develop Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease. If she does not receive antibiotics during labor, her chance of delivering a baby who will develop Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease is 1 in 200.

Pregnant women cannot take antibiotics to prevent early-onset Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease in newborns before labor. The bacteria can grow back quickly. The antibiotics only help during labor.

Streptococcus agalactiae infection in other ages and groups

Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) bacteria may come and go in people’s bodies without symptoms.

On average, about 1 in 20 non-pregnant adults with serious Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) infections die.

The rate of serious group B strep disease increases with age:

- There are 10 cases in every 100,000 non-pregnant adults each year.

- There are 25 cases in every 100,000 adults 65 years or older each year.

- The average age of cases in non-pregnant adults is about 60 years old.

Streptococcus agalactiae prevention

The two best ways to prevent Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease during the first week of a newborn’s life are:

- Testing pregnant women for Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) bacteria

- Giving antibiotics, during labor, to women at increased risk

Unfortunately, experts have not identified effective ways to prevent Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease in people older than one week old.

Testing pregnant women

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and American College of Nurse-Midwives (ACNM) recommend women get tested for Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) bacteria when they are 36 through 37 weeks pregnant. The test is simple and does not hurt. Clinicians use a sterile swab (“Q-tip”) to collect a sample from the vagina and the rectum. They send the sample to a laboratory for testing.

Women who test positive for Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) are not sick. However, they are at increased risk for passing the bacteria to their babies during birth.

Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) bacteria come and go naturally in people’s bodies. A woman may test positive for the bacteria at some times and not others. That is why doctors test women late in their pregnancy, close to the time of delivery.

Antibiotics during labor

Clinicians give antibiotics to women who are at increased risk of having a baby who will develop Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease. The antibiotics help protect babies from infection, but only if given during labor. Doctors cannot give antibiotics before labor begins because the bacteria can grow back quickly.

Clinicians give the antibiotic by IV (through the vein). Clinicians most commonly prescribe a type of antibiotic called beta-lactams, which includes penicillin and ampicillin. However, clinicians can also give other antibiotics to women who are severely allergic to these antibiotics. Antibiotics are very safe. For example, about 1 in 10 women have mild side effects from receiving penicillin. There is a rare chance (about 1 in 10,000 women) of having a severe allergic reaction that requires emergency treatment.

Vaccination

Currently, there is no vaccine to help pregnant women protect their newborns from Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) bacteria and disease. Researchers are working on developing a vaccine, which may become available in the future.

Strategies Proven Not to Work

The following strategies are not effective at preventing Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease in babies:

- Taking antibiotics by mouth

- Taking antibiotics before labor begins

- Using birth canal washes with the disinfectant chlorhexidine

Streptococcus agalactiae signs and symptoms

Symptoms of Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease are different in newborns compared to people of other ages who get GBS disease.

In Newborns and Their Mothers

The symptoms of Streptococcus agalactiae disease can seem like other health problems in newborns and babies. Symptoms include:

- Fever

- Difficulty feeding

- Irritability or lethargy (limpness or hard to wake up the baby)

- Difficulty breathing

- Blue-ish color to skin

Babies who get it in the first week of life have “early-onset GBS disease.” Most newborns with early-onset disease have symptoms on the day of birth. In contrast, babies who develop disease later can appear healthy at birth and during their first week of life.

Women who give birth to a baby who develops GBS disease usually do not feel sick or have any symptoms.

In Others

Symptoms depend on the part of the body that is infected. Listed below are symptoms associated with the most common infections caused by Streptococcus agalactiae bacteria.

Symptoms of bacteremia (blood stream infection) and sepsis (the body’s extreme response to an infection) include:

- Fever

- Chills

- Low alertness

Symptoms of pneumonia (lung infection) include:

- Fever

- Chills

- Cough

- Rapid breathing or difficulty breathing

- Chest pain

Skin and soft-tissue infections often appear as a bump or infected area on the skin that may be:

- Red

- Swollen or painful

- Warm to the touch

- Full of pus or other drainage

People with skin infections may also have a fever.

Bone and joint infections often appear as pain in the infected area and might also include:

- Fever

- Chills

- Swelling

- Stiffness or inability to use the affected limb or joint.

Streptococcus agalactiae complications

Babies may have long-term problems, such as deafness and developmental disabilities, due to having Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease. Babies who had meningitis are especially at risk for having long-term problems. Care for sick babies has improved a lot in the United States. However, 2 to 3 in every 50 babies (4% to 6%) who develop Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease will die.

Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) bacteria may also cause some miscarriages, stillbirths, and preterm deliveries. However, many different factors can lead to stillbirth, pre-term delivery, or miscarriage. Most of the time, the cause for these events is not known.

Serious Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) infections, such as bacteremia, sepsis, and pneumonia, can also be deadly for adults. On average, about 1 in 20 non-pregnant adults with serious Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) infections die. Risk of death is lower among younger adults and adults who do not have other medical conditions.

Streptococcus agalactiae diagnosis

If doctors suspect someone has Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease, they will take samples of sterile body fluids. Examples of sterile body fluids are blood and spinal fluid. Doctors look to see if Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) bacteria grow from the samples (culture). It can take a few days to get these results since the bacteria need time to grow. Doctors may also order a chest x-ray to help determine if someone has Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease.

Sometimes Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) bacteria can cause urinary tract infections (UTIs or bladder infections). Doctors use a sample of urine to diagnose urinary tract infections.

Streptococcus agalactiae treatment

Doctors usually treat Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) disease with a type of antibiotic called beta-lactams, which includes penicillin and ampicillin. Sometimes people with soft tissue and bone infections may need additional treatment, such as surgery. Treatment will depend on the kind of infection caused by Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) bacteria. Patients should ask their or their child’s doctor about specific treatment options.

Intravenous penicillin G is the treatment of choice for intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis against Group B Streptococcus[1]. Penicillin G 5 million units intravenous is administered as a loading dose, followed by 2.5 to 3 million units every 4 hours during labor until delivery 32. Ampicillin is a reasonable alternative to penicillin G if penicillin G is unavailable[1]. Ampicillin is administered as a 2 gm intravenous loading dose followed by 1 gm intravenous every 4 hours during labor until delivery 32.

Penicillin G and ampicillin should not be used in patients with penicillin allergy. Antibiotic prophylaxis in patients with a history of anaphylaxis, angioedema, respiratory distress, or urticaria following penicillin or cephalosporin is guided by antibiotic susceptibility testing 32. If Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) is sensitive to both clindamycin and erythromycin, then clindamycin 900 mg intravenous every 8 hours is recommended for Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) prophylaxis during labor until delivery 32. Occasionally Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) susceptibility testing will return susceptible to clindamycin but resistant to erythromycin. Resistance to erythromycin can induce resistance to clindamycin even in the presence of a culture that appears sensitive to clindamycin. For this reason, if the culture returns resistant to erythromycin, vancomycin 1 gm intravenously every 12 hours is recommended for Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) prophylaxis 32.

In patients without Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) susceptibility testing with penicillin allergy, vancomycin is recommended for Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) prophylaxis with dosing as described above 32.

Cefazolin 2 gram intravenous loading dose followed by 1 gm every 8 hours may be used in patients without a history of anaphylaxis, angioedema, respiratory distress, or urticaria following penicillin or cephalosporin administration 32.

Initiating antibiotic prophylaxis greater than 4 hours before delivery is considered to be adequate antibiotic prophylaxis and is effective in the prevention of transmission of Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) to the fetus. However, antibiotic prophylaxis administered at a shorter interval will provide some protection. If a patient presents in active labor and delivery is expected in less than 4 hours, antibiotic prophylaxis should still be initiated 20.

Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) vaccines show promise to combat early-onset Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) infection, but there are currently no approved Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) vaccines on the market 20.

Streptococcus agalactiae prognosis

Since the initiation of universal screening for Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) colonization and intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis, the incidence of early-onset Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) infection has decreased approximately 80% 20. Efficacy of intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis is estimated between 86% to 89% 20. Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) culture screening during prenatal care will not identify all women with Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) colonization during labor because genital tract colonization can be temporary. Approximately 60% of cases of early-onset Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) infection occur in neonates born to patients with negative Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) culture at 35 to 37 weeks 20.

Early-onset Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) infection typically presents in the first 24 to 48 hours of life. Symptoms include respiratory distress, apnea, with signs of sepsis 20. Sepsis and pneumonia commonly result from early-onset Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) infection, but rarely meningitis can occur 20. Mortality from early-onset Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) infection is much higher in preterm infants than term infants. Preterm infants with early-onset Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus [GBS]) infection have a case fatality rate between 20% to 30% compared to 2% to 3% in term infants 20.

References- Pietrocola G, Arciola CR, Rindi S, Montanaro L, Speziale P. Streptococcus agalactiae Non-Pilus, Cell Wall-Anchored Proteins: Involvement in Colonization and Pathogenesis and Potential as Vaccine Candidates. Front Immunol. 2018;9:602. Published 2018 Apr 5. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00602 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5900788

- Group B streptococcal disease in infants aged younger than 3 months: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012 Feb 11;379(9815):547-56. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61651-6. Epub 2012 Jan 4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61651-6

- Group B Strep (GBS) Clinical Overview. https://www.cdc.gov/groupbstrep/clinicians/index.html

- Breeding KM, Ragipani B, Lee KD, Malik M, Randis TM, Ratner AJ. Real-time PCR-based serotyping of Streptococcus agalactiae. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38523. Published 2016 Dec 2. doi:10.1038/srep38523 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5133537

- A multiplex PCR assay for the direct identification of the capsular type (Ia to IX) of Streptococcus agalactiae. J Microbiol Methods. 2010 Feb;80(2):212-4. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2009.11.010. Epub 2009 Dec 1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mimet.2009.11.010

- Metcalf BJ, Chochua S, Gertz RE Jr, et al. Short-read whole genome sequencing for determination of antimicrobial resistance mechanisms and capsular serotypes of current invasive Streptococcus agalactiae recovered in the USA.External Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;pii: S1198-743X(17):30118–0.

- Hickman ME, Rench MA, Ferrieri P, Baker CJ. Changing epidemiology of group B streptococcal colonization. Pediatrics (1999) 104(2 Pt 1):203–9.10.1542/peds.104.2.203

- Rajagopal L. Understanding the regulation of group B streptococcal virulence factors. Future Microbiol (2009) 4(2):201–21.10.2217/17460913.4.2.201

- Doran KS, Nizet V. Molecular pathogenesis of neonatal group B streptococcal infection: no longer in its infancy. Mol Microbiol (2004) 54(1):23–31.10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04266.x

- Schubert A, Zakikhany K, Schreiner M, Frank R, Spellerberg B, Eikmanns BJ, et al. A fibrinogen receptor from group B Streptococcus interacts with fibrinogen by repetitive units with novel ligand binding sites. Mol Microbiol (2002) 46(2):557–69.10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03177.x

- Spellerberg B, Rozdzinski E, Martin S, Weber-Heynemann J, Schnitzler N, Lütticken R, et al. Lmb, a protein with similarities to the LraI adhesin family, mediates attachment of Streptococcus agalactiae to human laminin. Infect Immun (1999) 67(2):871–8.

- Rosini R, Rinaudo CD, Soriani M, Lauer P, Mora M, Maione D, et al. Identification of novel genomic islands coding for antigenic pilus-like structures in Streptococcus agalactiae. Mol Microbiol (2006) 61(1):126–41.10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05225.x

- Brodt S, Pöhlchen D, Flanagin VL, Glasauer S, Gais S, Schönauer M. Rapid and independent memory formation in the parietal cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2016) 113(46):13251–6.10.1073/pnas.1605719113

- Gutekunst H, Eikmanns BJ, Reinscheid DJ. The novel fibrinogen-binding protein FbsB promotes Streptococcus agalactiae invasion into epithelial cells. Infect Immun (2004) 72(6):3495–504.10.1128/IAI.72.6.3495-3504.2004

- Liu GY, Doran KS, Lawrence T, Turkson N, Puliti M, Tissi L, et al. Sword and shield: linked group B streptococcal beta-hemolysin/cytolysin and carotenoid pigment function to subvert host phagocyte defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2004) 101(40):14491–6.10.1073/pnas.0406143101

- Buscetta M, Firon A, Pietrocola G, Biondo C, Mancuso G, Midiri A, et al. PbsP, a cell wall-anchored protein that binds plasminogen to promote hematogenous dissemination of group B Streptococcus. Mol Microbiol (2016) 101(1):27–41.10.1111/mmi.13357

- Santi I, Scarselli M, Mariani M, Pezzicoli A, Masignani V, Taddei A, et al. BibA: a novel immunogenic bacterial adhesin contributing to group B Streptococcus survival in human blood. Mol Microbiol (2007) 63(3):754–67.10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05555.x

- Pietrocola G, Rindi S, Rosini R, Buccato S, Speziale P, Margarit I. The group B Streptococcus-secreted protein CIP interacts with C4, preventing C3b deposition via the lectin and classical complement pathways. J Immunol (2016) 196(1):385–94.10.4049/jimmunol.1501954

- Derré-Bobillot A, Cortes-Perez NG, Yamamoto Y, Kharrat P, Couvé E, Da Cunha V, et al. Nuclease A (Gbs0661), an extracellular nuclease of Streptococcus agalactiae, attacks the neutrophil extracellular traps and is needed for full virulence. Mol Microbiol (2013) 89(3):518–31.10.1111/mmi.12295

- Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ., Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease–revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010 Nov 19;59(RR-10):1-36.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 485: Prevention of early-onset group B streptococcal disease in newborns. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Apr;117(4):1019-27.

- Seng P, Vernier M, Gay A, Pinelli PO, Legré R, Stein A. Clinical features and outcome of bone and joint infections with streptococcal involvement: 5-year experience of interregional reference centres in the south of France. New Microbes New Infect (2016) 12:8–17.10.1016/j.nmni.2016.03.009

- Salloum M, van der Mee-Marquet N, Domelier AS, Arnault L, Quentin R. Molecular characterization and prophage DNA contents of Streptococcus agalactiae strains isolated from adult skin and osteoarticular infections. J Clin Microbiol (2010) 8(4):1261–9.10.1128/JCM.01820-09

- Sendi P, Christensson B, Uçkay I, Trampuz A, Achermann Y, Boggian K, et al. Group B Streptococcus in prosthetic hip and knee joint-associated infections. J Hosp Infect (2011) 79(1):64–9.10.1016/j.jhin.2011.04.022

- Stoll BJ Hansen NI Sanchez PJ et al. Early onset neonatal sepsis: the burden of group B Streptococcal and E coli disease continues. Pediatrics. 2011; 127: 817-826

- Colbourn T Gilbert R. An overview of the natural history of early onset group B streptococcal disease in the UK. Early Hum Dev. 2007; 83: 149-156

- Guilbert J Levy C Cohen R Delacourt C Renolleau S Flamant C. Late and ultra late onset Streptococcus B meningitis: clinical and bacteriological data over 6 years in France. Acta Paediatr. 2009; 99: 47-51

- Remington JS Infectious disease of the fetus and the newborn infant. 7th edn. Elsevier Saunders, Philadephia 2011

- Walsh JA Hutchins S. Group B streptococcal disease: its importance in the developing world and prospect for prevention with vaccines. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989; 8: 271-277

- Colbourn TE Asseburg C Bojke L et al. Preventive strategies for group B streptococcal and other bacterial infections in early infancy: cost effectiveness and value of information analyses. BMJ. 2007; 335: 655

- Schrag SJ. Group B streptococcal vaccine for resource-poor countries. Lancet. 2011; 378: 11-12

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 485: Prevention of early-onset group B streptococcal disease in newborns. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Apr;117(4):1019-27