What is acral lentiginous melanoma

Acral lentiginous melanoma is a type of malignant melanoma originating on palms, soles of foot and under the nail (subungual melanoma). Acral lentiginous melanoma is a form of melanoma characterized by its site of origin: palm, sole, or beneath the nail (subungual melanoma). Acral lentiginous melanoma represents approximately 3 to 8% of all melanomas. Acral lentiginous melanoma does not represent the most common type of melanoma in any racial group in United States-based studies 1. Acral lentiginous melanoma is more common on feet than on hands. It can arise de novo in normal-appearing skin, or it can develop within an existing melanocytic nevus (mole). Acral lentiginous melanoma constitutes a substantially higher proportion of melanomas in dark-skinned individuals such as 70% of African Americans, 46% of Asians, and Hispanics. The majority of acral lentiginous melanoma lesions are tan to dark brown macule that are large (3 cm in diameter) with an irregular borders, but in advanced lesions it may be ulcerating or may present as a fungating mass. The majority arise in people over the age of 40 (median age, 59 years). Acral lentiginous melanoma is equally common in males and females. Subungual melanoma (melanoma beneath the nail) most commonly occurs on the great toe or thumb.

Although similar in clinical appearance to lentigo maligna melanoma, acral lentiginous melanoma is a biologically much more aggressive lesion, with a relatively short evolution to the vertical growth phase.

When acral lentiginous melanoma arises in the nail region, it is known as melanoma of the nail unit. If it starts in the matrix (nail growth area), it is called subungual melanoma. It may present as diffuse discoloration or irregular pigmented longitudinal band(s) on the nail plate. Advanced melanoma destroys the nail plate altogether. It can be amelanotic (non-pigmented).

Acral lentiginous melanoma starts as a slowly-enlarging flat patch of discolored skin. At first, the malignant cells remain within the tissue of origin, the epidermis. This is the in situ phase of melanoma, which can persist for months or years.

Acral lentiginous melanoma becomes invasive when the melanoma cells cross the basement membrane of the epidermis and malignant cells enter the dermis. A rapidly-growing nodular melanoma can also arise within acral lentiginous melanoma and proliferate more deeply within the skin.

The cause or causes of acral lentiginous melanoma are unknown. Due to the development of acral lentiginous melanoma on sun‐shielded locations, it is believed not to be related to UV exposure. Regardless of its biological origin, a history of trauma has frequently been proposed as an acral lentiginous melanoma trigger, since tumors develop on weight‐bearing areas of the body or sites that are highly susceptible to mechanical injury such as palms and soles 2.

When diagnosed early, melanoma is often curable through a surgical excision of the lesion. Unfortunately, the diagnosis of early‐stage acral lentiginous melanoma remains challenging as diagnostic features are often subtle 3. Acral lentiginous melanoma lesions are often diagnosed at later stages, and it is common for them to be misdiagnosed as fungal infections, warts, diabetic foot ulcers or traumatic ulcers 4. Furthermore, differential diagnosis may be complex considering other pigmented and unpigmented and bleeding tumors (pyogenic granulomas) often seen on acral skin. Misdiagnosis has been observed to be associated with increased median tumor thickness, more advanced stage at diagnosis and lower 5‐year survival 5. Misdiagnosis is also associated with low socioeconomic status, lack of prompt access to assessment by a dermatologist, lack of full body examination during regular primary care physician consultation, low interest and insufficient education regarding skin cancer in the medical school curricula and a highly demanded and saturated public healthcare system 2.

The initial treatment of primary melanoma is to cut it out; the lesion should be completely excised with a 2–3 mm margin of healthy tissue. Further treatment depends mainly on the Breslow thickness of the lesion. A flap or graft may be needed to close the wound. In the case of acral lentiginous and subungual melanoma, this may include partial amputation of a digit. Occasionally, the pathologist will report incomplete excision of the melanoma, despite wide margins requiring further surgery or radiotherapy to ensure the tumor has been completely removed.

Acral lentiginous melanoma key facts

- Acral lentiginous melanoma cause is unknown.

- Acral lentiginous melanoma is not related to sun exposure

- Acral lentiginous melanoma affects men and women equally

- Acral lentiginous melanoma affects all skin types, and is the most common type of melanoma in dark-skinned patients

- The majority of acral lentiginous melanoma arise in patients over the age of 40

- Acral lentiginous melanomas grow relatively slowly in the early stages, although a reliable history can be difficult, especially for lesions on the soles

- Acral lentiginous melanoma are more common on the soles

- Acral lentiginous melanoma initially present as slow growing deceptively banal-looking pigmented macules or patches, hence the term lentiginous

- The development of nodular areas within the lesion suggests deeper invasion.

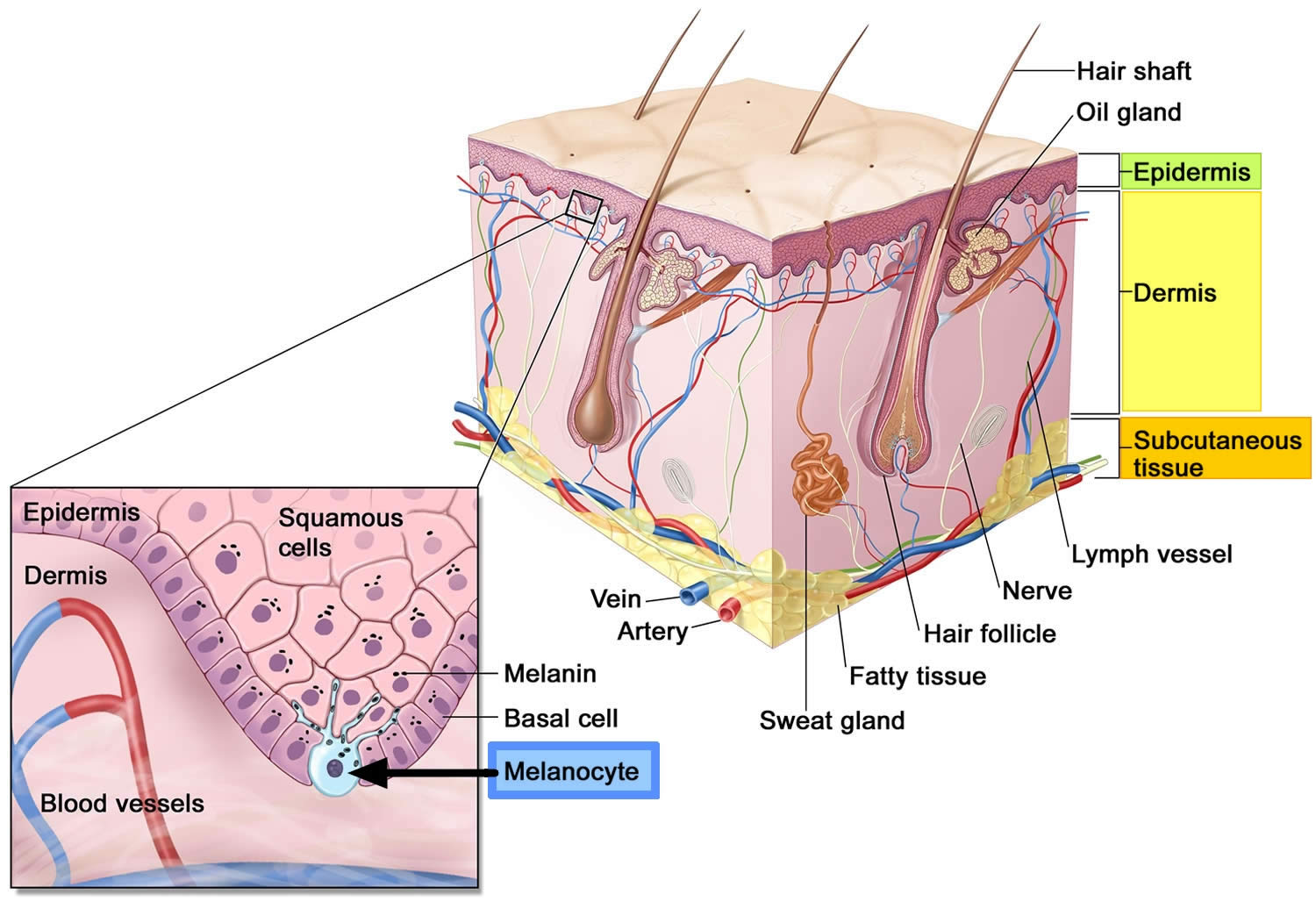

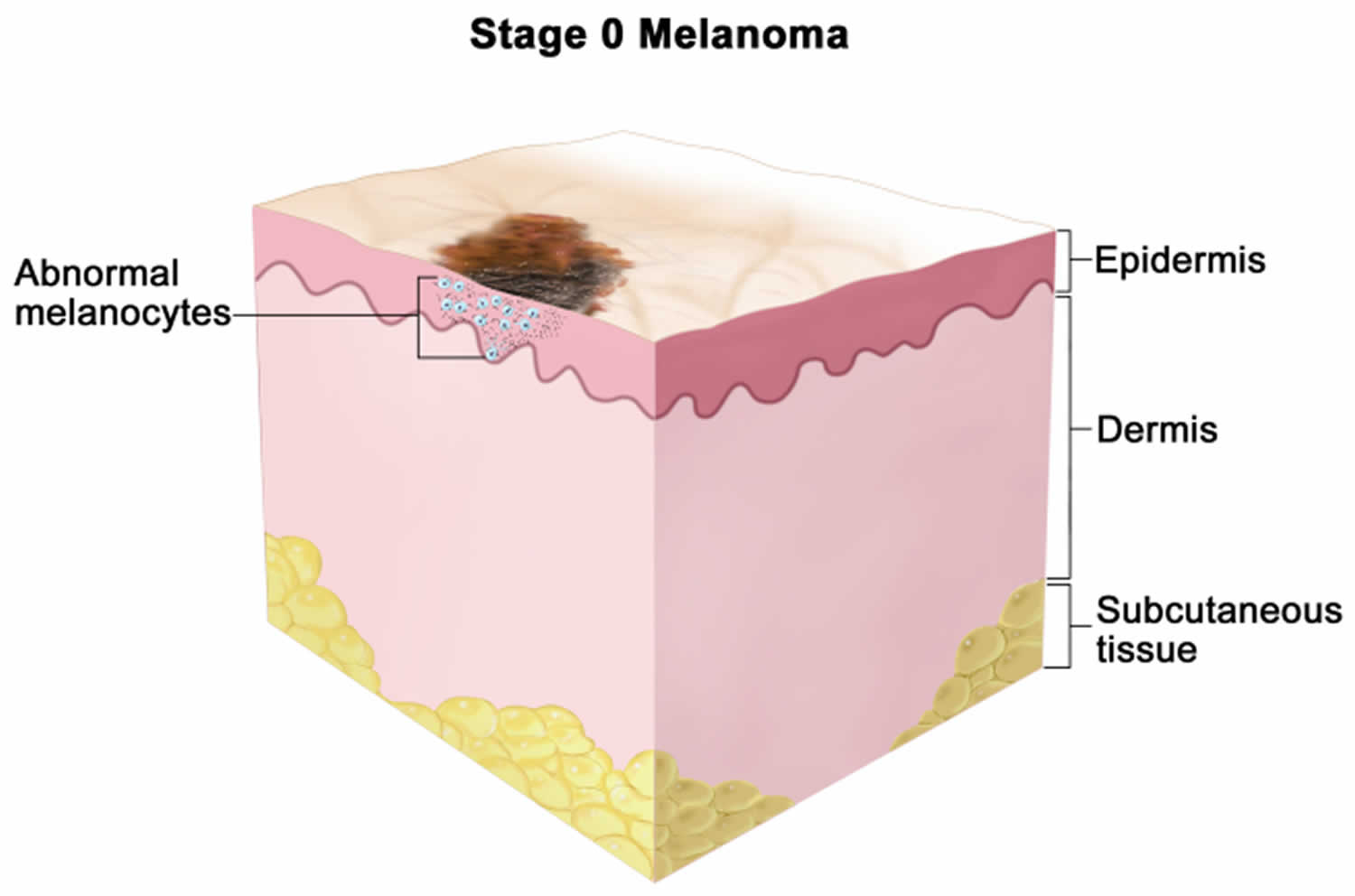

Figure 1. Anatomy of the skin

Footnote: Anatomy of the skin, showing the epidermis, dermis, and subcutaneous tissue. Melanocytes are in the layer of basal cells at the deepest part of the epidermis. Melanoma also called malignant melanoma or cutaneous melanoma, is the most serious type of skin cancer that begins in the melanocytes of the skin (a type of skin cells that produce melanin and melanin gives your skin its color) (see Figure 1 above).

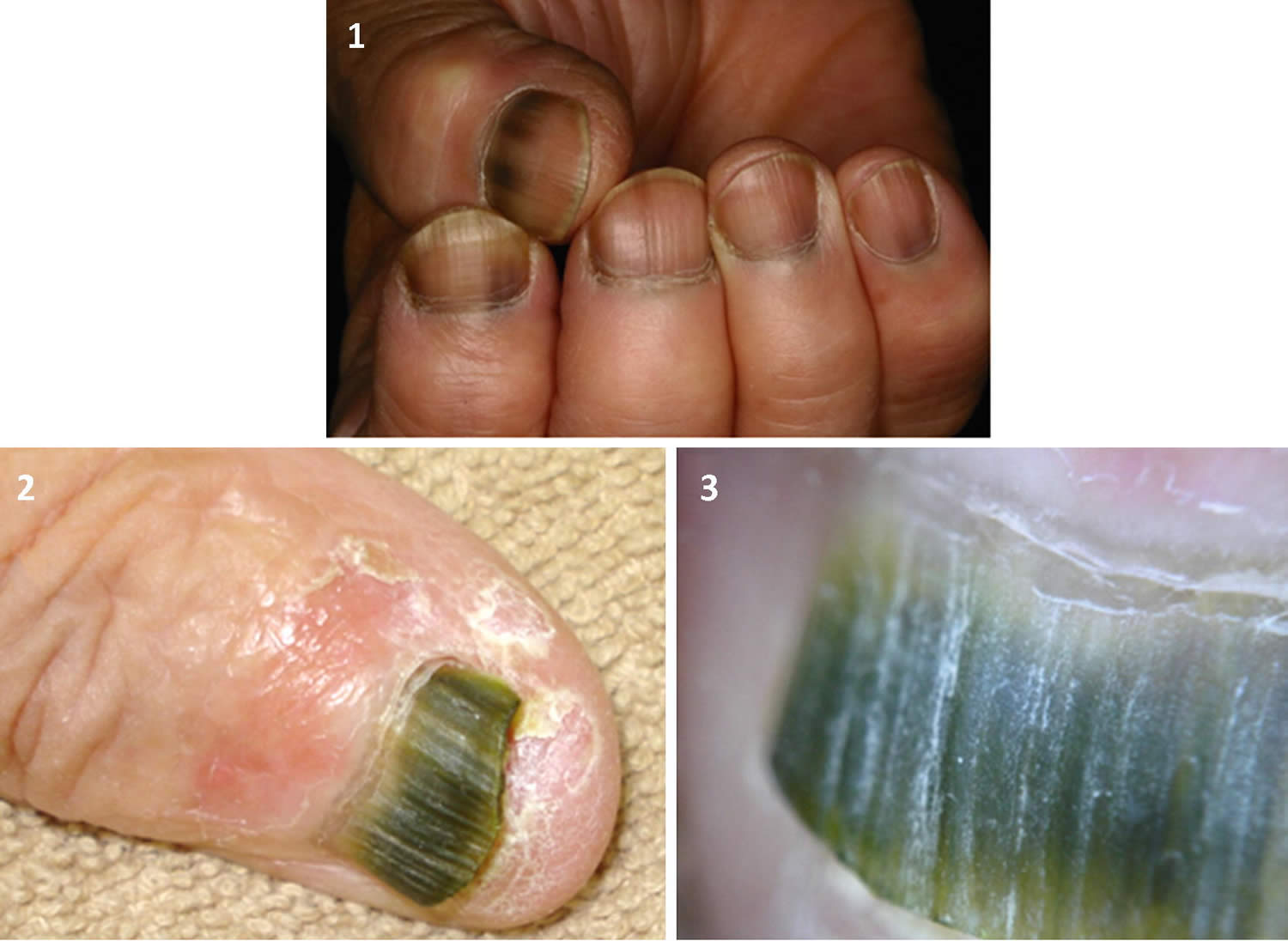

Figure 2. Acral lentiginous melanoma foot

Figure 3. Subungual melanoma

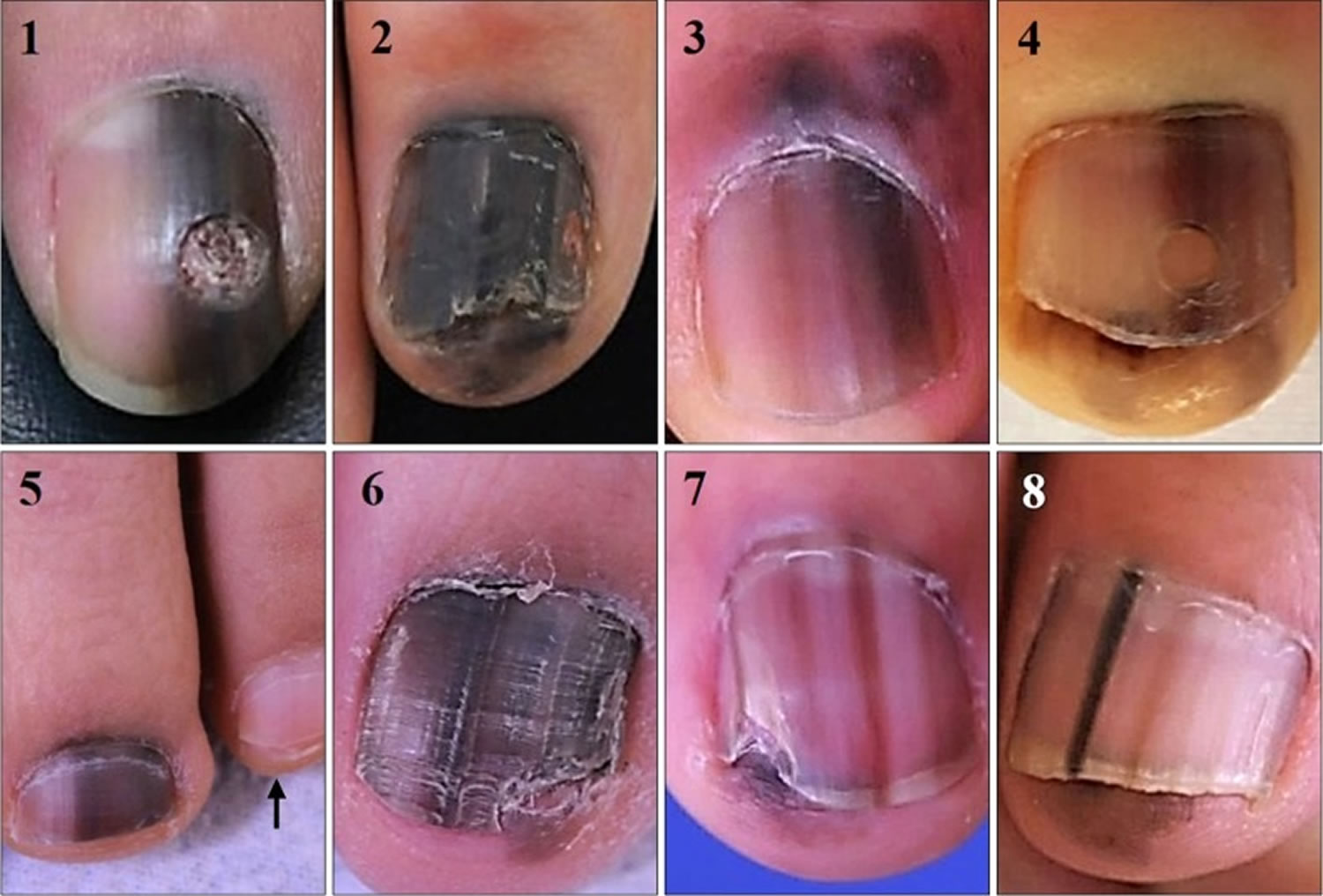

[Source 6 ]Figure 4. Acral lentiginous melanoma toenail

Footnote: Clinical photographs of 8 subungual melanoma in situ cases. Note all cases have entirely pigmented nail plate compared to unaffected ones (arrow in case 5). Hutchinson’s sign was observed except for case 1. Cases 2 and 6 had nail deformity ahead of nail matrix biopsy.

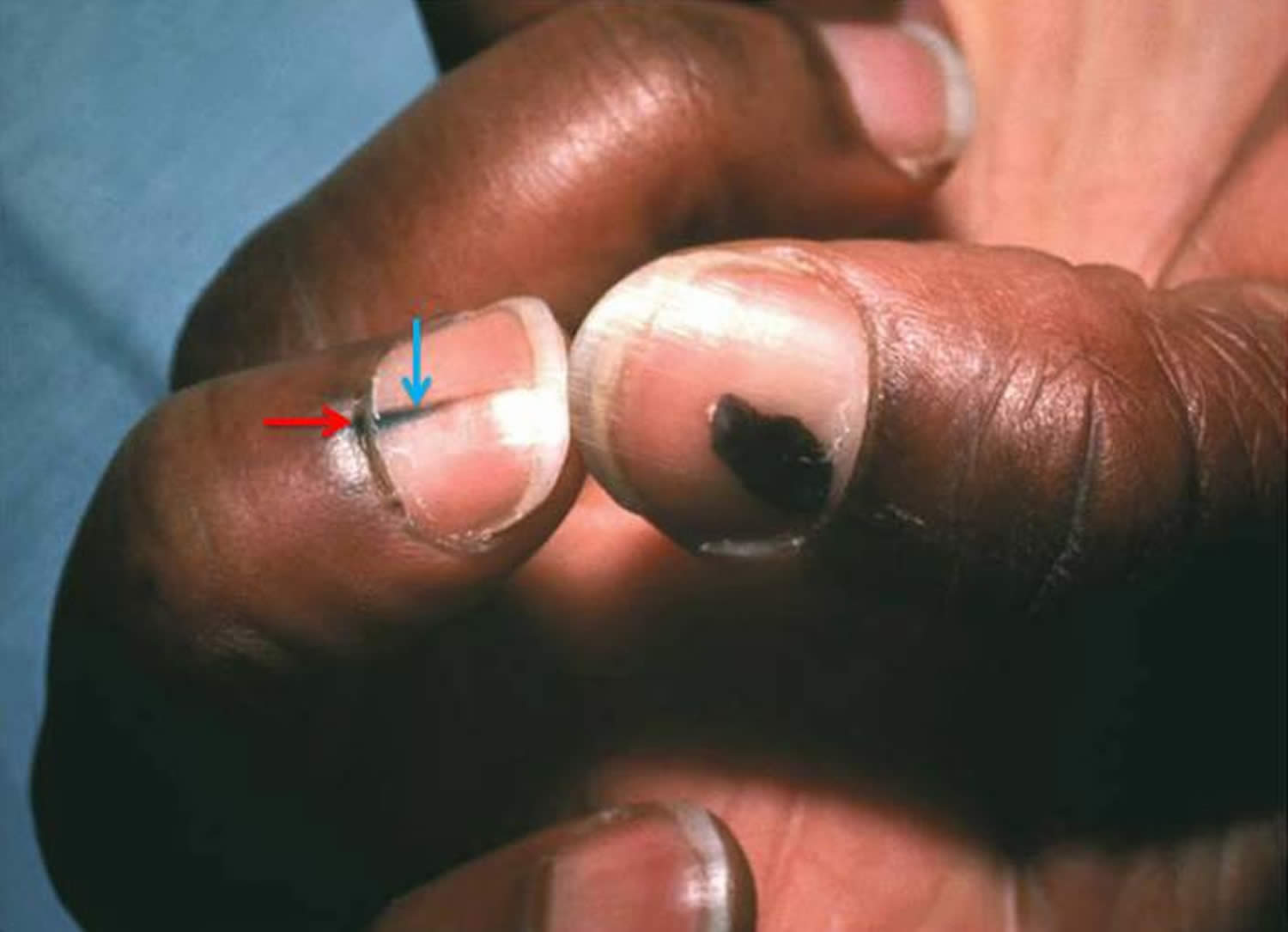

[Source 7 ]Figure 5. Acral lentiginous melanoma (Hutchinson sign [red arrow])

Footnote: Longitudinal pigmentation of the nail (melanonychia striata; blue arrow) and hyperpigmentation extending across lunula to proximal nail fold (Hutchinson sign; red arrow) of the middle finger with rounded pigmented lesion of the thumbnail. This patient was diagnosed with acral-lentiginous melanoma.

[Source 8 ]Figure 6. Subungual acral lentiginous melanoma

Footnotes: (A) large pigmented lesions associated with irregular colours, broad band of pigment, ill-defined edges and nail dystrophy; (B) pigmented lesion with involvement of 100% of the nail bed, nail dystrophy, Hutchinson’s sign (pigmentation in the skin of the proximal nail fold) and pigmentation of the surrounding skin distally; (C) broad pigmented lesion, irregular color, ill-defined edges, Hutchinson’s sign and pigmentation in the skin distally; (D) amelanotic lesion with destruction of the overlying nail plate and the proximal nail fold; (E and F) ulcerated fungating lesion that has replaced the entire nail apparatus, with a satellite lesion located in the pulp skin distally

[Source 9 ]What is Breslow thickness?

Breslow thickness is reported for invasive melanomas. The Breslow thickness is measured vertically in millimeters (mm) from the top of the granular layer (or base of superficial ulceration) to the deepest point of tumor involvement. Breslow thickness is measured in millimeters (mm) with a small ruler, called a micrometer. A specialist doctor called a pathologist uses the special ruler with a microscope when looking at your tissue sample in the laboratory. The Breslow thickness is a strong predictor of outcome; the thicker the melanoma, the more likely it is to metastasize (spread). Doctors use the Breslow thickness in another staging system for melanoma called the TNM staging system.

What is the Clark level of invasion?

The Clark level indicates the anatomic plane of melanoma invasion. The Clark scale is a way of measuring how deeply the melanoma has grown into the skin and which levels of the skin are affected. You can see the main layers of the skin in Figure 1 above. The deeper the Clark level, the greater the risk of metastasis (secondary spread). The Clark level is useful in predicting outcome in thin tumors, and less useful for thicker ones in comparison to the value of the Breslow thickness.

Table 1. The Clark scale has 5 levels

| Level | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Level 1 | In situ melanoma – the melanoma cells are only in the outer layer of the skin (the epidermis) |

| Level 2 | Melanoma has invaded papillary dermis (superficial dermis) |

| Level 3 | Melanoma cells are touching the next layer down known as the reticular dermis (deep dermis) |

| Level 4 | Melanoma has invaded reticular dermis |

| Level 5 | Melanoma has invaded subcutaneous tissue |

What is TNM Staging system?

Most melanoma specialists refer to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system, which is based on 3 key pieces of information:

- The extent of the main (primary) tumor (T): How deep has the cancer grown into the skin? Is the cancer ulcerated?

- Tumor thickness: The thickness of the melanoma is called the Breslow thickness. In general, melanomas less than 1 millimeter (mm) thick (about 1/25 of an inch) have a very small chance of spreading. As the melanoma becomes thicker, it has a greater chance of spreading.

- Ulceration: Ulceration is a breakdown of the skin over the melanoma. Melanomas that are ulcerated tend to have a worse outlook.

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has the cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes?

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to distant lymph nodes or distant organs ? (Melanoma can spread almost anywhere in the body, but the most common sites of spread are the lungs, liver, brain, bones, and the skin or lymph nodes in other parts of the body.)

Numbers or letters after T, N, and M provide more details about each of these factors. Higher numbers mean the cancer is more advanced. Once a person’s T, N, and M categories have been determined, this information is combined in a process called stage grouping to assign an overall stage.

Table 2. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM Staging System

| AJCC Stage | Melanoma Stage Description | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | This stage is also known as melanoma in situ. The cancer is confined to the epidermis, the outermost skin layer (Tis). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant parts of the body (M0). | |

| 1 | The tumor is no more than 2 mm (2/25 of an inch) thick and might or might not be ulcerated (T1 or T2a). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant parts of the body (M0) | |

| 2 | The tumor is more than 2 mm thick (T2b or T3) and may be thicker than 4 mm (T4). It might or might not be ulcerated. The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant parts of the body (M0). | |

| 3A | The tumor is no more than 2 mm thick and might or might not be ulcerated (T1 or T2a). The cancer has spread to 1 to 3 nearby lymph nodes, but it is so small that it is only seen under the microscope (N1a or N2a). It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | |

| 3B | There is no sign of the primary tumor (T0) AND: The cancer has spread to only one nearby lymph node (N1b) OR It has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor (without reaching the nearby lymph nodes) (N1c) It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | |

| OR | ||

| The tumor is no more than 4 mm thick and might or might not be ulcerated (T1, T2, or T3a) AND: The cancer has spread to only one nearby lymph node (N1a or N1b) OR It has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor (without reaching the nearby lymph nodes) (N1c) OR It has spread to 2 or 3 nearby lymph nodes (N2a or N2b) It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | ||

| 3C | There is no sign of the primary tumor (T0) AND: The cancer has spread to 2 or more nearby lymph nodes, at least one of which could be seen or felt (N2b or N3b) OR It has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor, and it has reached the nearby lymph nodes (N2c or N3c) OR It has spread to nearby lymph nodes that are clumped together (N3b or N3c) It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | |

| OR | ||

| The tumor is no more than 4 mm thick, and might or might not be ulcerated (T1, T2, or T3a) AND: The cancer has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor, and it has reached nearby lymph nodes (N2c or N3c) OR The cancer has spread to 4 or more nearby lymph nodes (N3a or N3b), or it has spread to nearby lymph nodes that are clumped together (N3b or N3c) It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | ||

| OR | ||

| The tumor is more than 2 mm but no more than 4 mm thick and is ulcerated (T3b) OR it is thicker than 4 mm but is not ulcerated (T4a). The cancer has spread to one or more nearby lymph nodes AND/OR it has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor (N1 or higher). It has not spread to distant parts of the body. | ||

| OR | ||

| The tumor is thicker than 4 mm and is ulcerated (T4b) AND: The cancer has spread to 1 to 3 nearby lymph nodes, which are not clumped together (N1a/b or N2a/b) OR It has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor, and it might (N2c) or might not (N1c) have reached 1 nearby lymph node) It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | ||

| 3D | The tumor is thicker than 4 mm and is ulcerated (T4b) AND: The cancer has spread to 4 or more nearby lymph nodes (N3a or N3b) OR It has spread to nearby lymph nodes that are clumped together (N3b) It has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor, AND it has spread to at least 2 nearby lymph nodes, or to lymph nodes that are clumped together (N3c) OR It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | |

| 4 | The tumor can be any thickness and might or might not be ulcerated (any T). The cancer might or might not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (any N). It has spread to distant lymph nodes or to organs such as the lungs, liver or brain (M1). | |

Footnotes: The staging system in the table above uses the pathologic stage also called the surgical stage. This is determined by examining tissue removed during an operation. Sometimes, if surgery is not possible right away (or at all), the cancer will be given a clinical stage instead. This is based on the results of physical exams, biopsies, and imaging tests. The clinical stage will be used to help plan treatment. Sometimes, though, the cancer has spread farther than the clinical stage estimates, so it may not predict a person’s outlook as accurately as a pathologic stage. If your cancer has been clinically staged, it is best to talk to your doctor about your specific stage.

[Source 10 ]Who gets acral lentiginous melanoma?

About 3 to 5% of melanomas are acral lentiginous melanoma. Melanoma is a potentially serious skin cancer that arises from pigment cells (melanocytes). Although acral lentiginous melanoma is rare in Caucasians and people with darker skin types, it is the most common subtype in people with darker skins.

Acral lentiginous melanoma is relatively rare compared to other types of melanoma. There is no connection with the color of skin (skin phototype) and it occurs at equal rates in white, brown or black skin 11. Acral lentiginous melanoma accounts for 29-72% of melanoma in dark-skinned individuals but less than 1% of melanoma in fair skinned people, as they are prone to more common sun-induced types of melanoma such as superficial spreading melanoma and lentigo maligna melanoma.

Acral lentiginous melanoma is equally common in males and females. The majority arise in people over the age of 40.

The cause or causes of acral lentiginous melanoma are unknown. It is believed not to be related to sun ultraviolet (UV) exposure.

Studies from Mexico, Taiwan, and China have found acral lentiginous melanoma to be the most common subtype in their populations 12, 13, 14. In two United States population-based registry studies, Bradford et al. 15 and Huang et al. 16 found that acral lentiginous melanoma accounted for 33-36% of cutaneous malignant melanoma in Blacks. Acral lentiginous melanoma represented 18-23.1% of total cutaneous malignant melanoma in Asian/Pacific Islanders. Acral lentiginous melanoma represented 9% of cutaneous malignant melanoma diagnosed in Hispanic Whites and only 1% in non-Hispanic Whites. Incidence rates of acral lentiginous melanoma were highest in Hispanic Whites at 2.5 per 1,000,000 person-years and significantly lower in Blacks, Non-Hispanic Whites, and Asian/Pacific Islanders at 1.8, 1.8, and 1.1 per 1,000,000 person-years, respectively 15. Melanoma specific survival was lower in Black and Hispanic White populations at 5 and 10 years than whites; however, when controlled for Breslow thickness, no difference was seen. This is thought to be attributable to the advanced stage at presentation in these minority groups 16.

Acral lentiginous melanoma causes

Acral lentiginous melanoma cause is unknown. Typical mutations identified in other types of cutaneous malignant melanoma, which are ultraviolet radiation-induced, are not identified in acral lentiginous melanoma 17. Acral lentiginous melanoma is due to the development of malignant pigment cells (melanocytes) along the basal layer of the epidermis (see Figure 1 above). These cells may arise from an existing melanocytic nevus or more often from previously normal-appearing skin. What triggers the melanocytes to become malignant is unknown but it involves genetic mutations.

Common gene mutations in acral lentiginous melanoma include KIT, BRAF, NRAS, and NF1 17. Specifically, KIT copy number gains are seen in up to 36% of acral melanomas, which is thought to be the most common mutation in acral lentiginous melanoma, which is much higher than other cutaneous malignant melanoma. In one study, the most commonly identified molecular aberration was chromosomal instability in the Cyclin D1 gene and was seen in 45% of acral lentiginous melanoma 18. Cytologically typical melanocytes which surround the atypical lesion often harbor KIT copy number gains and Cyclin D1 mutations, which is a concept known as ‘field effect’ and may explain local recurrences after excision of the clinical lesion.

In a paper on fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis of acral lentiginous melanoma, CCND1 gains, MYC gains, and CDKN2A loss were common alterations seen in their cohort 18. TERT promoter mutations, commonly found in UV-radiation induced melanomas, are not prevalent in acral lentiginous melanoma; however, other mutations involving the TERT gene including copy gains, translocations, missense, and promoter mutations were found in up to 41% of cases 17. It has been proposed by Su, J. et al. 19 that the carcinogenesis of acral lentiginous melanoma could be ethnicity dependent, which might help explain the large variety of genetic aberrations seen in the literature.

Although so far, no familial cases of acral lentiginous melanoma have been reported, there is scattered evidence suggesting that some genetic risk factors might exist 2. For instance, a large cohort study (a type of observational study that follows research participants over a period of time, often many years) observed an increased risk of any major melanoma subtype in patients with first‐degree relatives (parent, sibling, or child of an individual) diagnosed with acral lentiginous melanoma 20, suggesting some shared genetic factors with other melanoma subtypes. Another study found that acral lentiginous melanoma patients had secondary cancers and a family history of cancer more often than patients with other melanoma subtypes 21. Similarly, another large study showed a positive association between the number of nevi (moles) and risk of acral melanoma 22 or of rare melanoma subtypes, which included acral lentiginous melanoma 23.

Multiple studies have proposed stress or shearing force as a mechanism for the induction of acral lentiginous melanomas, as the incidence is higher in the weight-bearing areas that are highly susceptible to mechanical injury such as the foot, the heel, forefoot, and lateral side of the foot 24, 25, 26. Melanoma in the arch is rarer, however, was found to occur more frequently in obese patients 27. In this regard, a retrospective study on 685 Chinese acral melanoma patients found an association between prior trauma and disease development at the tumor site 28. Additionally, other studies have indicated that the most common location where acral lentiginous melanoma arises is the foot, in accordance with this being the site under the highest mechanical stress, and have suggested that tumor location in this region overlaps with the highest pressure areas on the plantar foot 29, 26, 24. However, the trauma theory remains contentious, as other studies have not found this correlation; for example, a retrospective study of 122 acral melanomas from the Mayo Clinic found no significant difference in the distribution of acral melanomas on weight‐bearing and non‐weight‐bearing regions 27. Additionally, analyses of the incidence of acral lentiginous melanoma in African tribes did not find differences in incidence between groups who wore shoes or were barefoot, although sample sizes were limited 30. Most recently, Ghanavatian et al. 31 found that once corrected for surface area, acral lentiginous melanoma was inversely proportional to atypical acral nevi and benign acral nevi in weight-bearing areas of the foot. Acral lentiginous melanoma may have an increased incidence on plantar surfaces compared to the palm, due to 50% more melanocytic density on the sole 32. There has been some correlation in the literature with penetrative injuries increasing the likelihood of acral lentiginous melanoma compared to control patients without penetrative injury 33.

Given the observations cited above, the origin of acral lentiginous melanoma may be multifactorial, characterized by an interaction between common genetic variants of small effect and certain environmental cues, such as trauma 2. Gene/environment interactions have previously been demonstrated for other melanoma subtypes, for which both genetic variants in genes such as MC1R and environmental exposures such as UV light are established risk factors. Usually, large‐scale case/control cohort genotyping and genome‐wide association testing are necessary to elucidate the influence of these etiological agents; however to date, no such studies have been published for acral lentiginous melanoma.

Acral lentiginous melanoma prevention

As researchers do not yet know what causes acral lentiginous melanoma, they also do not know how to prevent it. The best opportunity for a favorable outcome is an early diagnosis. Acral lentiginous melanoma is rare, but it can be deadly. Monitoring the skin for changes can be life-saving. It is important to schedule annual skin examinations with your doctor and to make sure your doctor checks the palms of your hands, the soles of your feet, and your nail beds. If an unexplained lesion appears on your hand, foot, or nail, you should see your dermatologist as soon as possible so that s/he can take a biopsy of the area and decide whether the spot is cancerous. As with any form of melanoma, diagnosing it early is key.

Acral lentiginous melanoma symptoms

Acral lentiginous melanoma on palm, soles or fingers and toes starts off as an enlarging patch of discolored skin. It is often thought at first to be a stain. Acral lentiginous melanoma can also be amelanotic (non-pigmented, usually red in color). Like other flat forms of melanoma, it can be recognized by the ABCDE checklist: Asymmetry, Border irregularity, Color variation, large Diameter and Evolving.

The ABCDE checklist can be used to check for the main warning signs of melanoma:

- A is for asymmetrical shape. Look for moles with irregular shapes, such as two very different-looking halves. Melanomas usually have 2 very different halves and are an irregular shape

- B is for irregular border. Look for moles with irregular, notched or scalloped borders — characteristics of melanomas. Melanoma often has an irregular appearance, however, if a symmetrical lesion continues to grow out of proportion to the patient’s other moles, especially if aged > 45, then melanoma must be considered

- C is for changes in color. Look for growths that have many colors (a mix of 2 or more colors) or an uneven distribution of color.

- D is for diameter. Look for new growth in a mole larger than 1/4 inch (about 6 millimeters).

- Melanoma grow at different rates – even if the lesion is not changing, if it looks suspicious or if you notice any skin changes that seem unusual make an appointment with your doctor.

- E is for evolving. Look for changes over time, such as a mole that grows in size or that changes color or shape. Moles may also evolve to develop new signs and symptoms, such as new itchiness or bleeding.

The characteristics of acral lentiginous melanoma include:

- Large size: >6 mm and often several centimeters or more in diameter at diagnosis

- Variable pigmentation: most often a mixture of brown, and blue-grey, black and red colors

- Smooth surface at first, later becoming thicker with an irregular surface that may be dry or warty

- Ulceration or bleeding

It is important to note that cancerous (malignant) moles vary greatly in appearance. Some may show all of the changes listed above, while others may have only one or two unusual characteristics.

Acral lentiginous melanoma is most commonly an acquired lesion and is associated with a previously existing nevus (moles) in less than 11% of cases 34. Acral lentiginous melanoma typically begins as a macule (a small patch of skin that is altered in color, but is not elevated) progressing to a patch with variable light to dark brown pigment. The edges are typically angular, often following the ridges of the dermatoglyphics (ridge patterns of the skin). As the lesion progresses and invades, it may become nodular and darkly pigmented, appearing blue to black. Ulceration may occur as the lesion becomes more nodular.

Acral lentiginous melanoma complications

Large excisions of acral lentiginous melanoma, particularly on the hands, can lead to contractures and painful scarring, which can lead to significant morbidity 35. If digit or limb amputation is required for treatment, patients can experience significant interference with activities of daily living, loss of function of the affected limb, phantom pain, and poor cosmetic outcomes 36.

Acral lentiginous melanoma diagnosis

Assessment begins with a thorough history of the lesion. This includes noting the duration, changes over time and preceding trauma. It is important not to exclude a diagnosis of malignancy solely on a history of trauma, as many patients with a acral lentiginous melanoma will recall an injury to the digit 37. A general medical history, including medications, and a personal and family history of melanoma are important to elicit.

Clinical examination begins with observation. The size, nature and distribution of nail discoloration should be recorded. Further details of the color pattern should also be documented, including whether it is homogenous or heterogenous, and if it contains regular or irregular, thick or thin bands of colour. The percentage of the nail bed that is occupied by the lesion should be noted. The presence of a Hutchinson’s sign should alert the clinician to the likelihood of a malignant process and can be seen as pigmentation in the skin of the proximal nail fold. Further signs of invasive disease include nail dystrophy and ulceration. Figure 6 above shows a spectrum of clinical appearances of subungual melanoma.

Dermoscopy

Dermoscopy or the use of a dermatoscope, by a dermatologist or other doctor trained in its use can be very helpful in distinguishing acral lentiginous melanoma from other skin lesions, particularly 38:

- Melanocytic nevi (moles)

- Viral warts

- Bleeding i.e. subcorneal hemorrhage or subungual haematoma

The most frequently observed dermoscopic features of acral lentiginous melanoma are 38:

- Asymmetrical structure and colors

- Parallel ridge pattern of pigment distribution

- Blue-grey structures

- broad bands of pigment (>3 mm)

- Dark brown to black color

- Irregular colors

- Fuzzy or blurred lateral borders

- Irregular bands that are not parallel, often wider at the proximal end

- Presence of pigmentation on the adjacent skin (Hutchinson’s sign)

- Nail dystrophy and/or ulceration.

Two systems to assess pigmented acral lesions on dermoscopy have been proposed. The first by Koga and Saida is a 3-step algorithm 39. Concerning features of an acral lesion on dermoscopy, include a parallel ridge pattern and/or lack of typical features of an acral nevus (i.e., fibrillar, lattice-like, and parallel furrow patterns) and a size greater than 7 mm 39. The second, by Lallas et al. 40, uses six dermatoscopic variables to assess the likelihood of acral lentiginous melanoma under the acronym BRAAFF. Four positive variables include blotches, ridge pattern, asymmetry of structures, and colors, and two negative variables include furrow pattern and fibrillar pattern. Despite the dermoscopic and clinical appearance, lesions greater than 7 mm in diameter should be biopsied, and all lesions greater than 9 mm are likely to be melanoma 38.

Acral lentiginous melanoma of the nail unit will often present as diffuse pigmentation of the nail, pigmented striping of the nail, or other non-pigmented changes, such as ulceration. The thumb and great toe are the site of subungual acral lentiginous melanoma in 92% of cases 32. When pigment from a subungual acral lentiginous melanoma extends into the nail fold, it is known as Hutchinson sign and is a worrisome clinical feature (see Figure 5 above). The lesion may begin as a subungual acral lentiginous melanoma with pigment isolated to the nail fold; however, extension into the adjacent glabrous skin is common with advanced lesions.

If the patient is shown to have the local cutaneous disease and is otherwise asymptomatic, imaging studies and other laboratory tests such as blood work are not recommended 41. In later stage disease, lactate dehydrogenase levels, while not usually the sole indicator of metastatic disease, are a good predictor of survival in patients with stage 4 disease 42.

Radiologic assessment to detect occult nodal disease or distant metastases has a high rate of false positives. However, if imaging is obtained, a chest x-ray should be considered as a cost-effective option. Imaging done without good reason may result in unnecessary invasive procedures. The American Academy of Dermatology suggests yearly skin exam and regional lymph node palpation as sufficient to assess for recurrence 41.

Sentinel lymph node biopsies have high prognostic value in intermediate and thick melanomas. A sentinel lymph node is defined as the first lymph node to which cancer cells are most likely to spread from a primary tumor. In patients with intermediate thickness melanomas and sentinel lymph node metastases, the melanoma-specific survival was 62.1% when sentinel lymph node biopsy and completion lymphadenectomy were performed, but only 41.5% in the observation group who had a completion lymphadenectomy after clinical nodal metastases were identified 43. The melanoma-specific survival was not affected significantly in patients with thick melanomas who underwent sentinel lymph node biopsy. Despite the previously mentioned study, these findings do remain controversial, with many authors questioning the survival benefit of sentinel lymph node biopsies 41.

Biopsy

If the skin lesion is suspicious of acral lentiginous melanoma, it is best cut out (excision biopsy), however, it is acknowledged in the recommendations that this may be impractical on an acral site 41. A partial biopsy is best avoided, except in unusually large lesions. An incisional or punch biopsy could miss a focus of melanoma arising in a pre-existing nevus. However, sometimes the lesion is very large, and before performing significant surgery, a biopsy is arranged to confirm the diagnosis. Biopsy of a lesion suspicious of acral lentiginous melanoma should remove a long ellipse of skin, or there should be several biopsies taken from multiple sites, as a single site could miss a malignant focus.

The pathological diagnosis of melanoma can be very difficult. Histological features of acral lentiginous melanoma includes asymmetric diffuse proliferation of large atypical melanocytes along the dermoepidermal junction with a lentiginous growth pattern with marked acanthosis and elongation of the rete ridges 3.

Pathology report

The pathologist’s report should include a macroscopic description of the specimen and melanoma (the naked eye view), and a microscopic description.

- Diagnosis of primary melanoma

- Breslow thickness to the nearest 0.1 mm

- Clark level of invasion

- Margins of excision i.e. the normal tissue around the tumor

- Mitotic rate – a measure of how fast the cells are proliferating

- Whether or not there is ulceration

The report may also include comments about the cell type and its growth pattern, invasion of blood vessels or nerves, inflammatory response, regression and whether there is an associated nevus (original mole).

Acral lentiginous melanoma differential diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for a patient presenting with a subungual lesion are broad. Lesions can be divided into melanocytic and non-melanocytic. They can also be categorized as neoplastic, traumatic, infective, systemic and drug-induced.

Acral lentiginous melanoma differential diagnoses could include:

- Melanocytic lesions

- nevi (moles)

- lentigo (increased single melanocytes)

- melanoma in situ

- melanoma

- Subungal squamous cell carcinoma (SCC)

- Subungual haemorrhage

- Fungal infection

- Systemic illness (including systemic lupus erythematosus, scleroderma)

- Drug-induced pigmentation

- Ethnic-type pigmentation (can often involve multiple digits).

Longitudinal melanonychia is a specific appearance of a linear, pigmented band on the nail plate. This appearance in itself is non-specific and can result from the same variety of diagnoses listed above for any subungual pigmentation. Early subungual melanoma often presents as longitudinal melanonychia.

Melanoma Skin Cancer Stages

After someone is diagnosed with melanoma, doctors will try to figure out if it has spread, and if so, how far. This process is called staging. The stage of a cancer describes how much cancer is in the body. It helps determine how serious the cancer is and how best to treat it. Doctors also use a cancer’s stage when talking about survival statistics.

The earliest stage melanomas are called stage 0 (carcinoma in situ), and then range from stages I (1) through IV (4). As a rule, the lower the number, the less the cancer has spread. A higher number, such as stage IV, means cancer has spread more. And within a stage, an earlier letter means a lower stage. Although each person’s cancer experience is unique, cancers with similar stages tend to have a similar outlook and are often treated in much the same way.

Most melanoma specialists refer to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system, which is based on 3 key pieces of information:

- The extent of the main (primary) tumor (T): How deep has the cancer grown into the skin? Is the cancer ulcerated?

- Tumor thickness: The thickness of the melanoma is called the Breslow thickness. In general, melanomas less than 1 millimeter (mm) thick (about 1/25 of an inch) have a very small chance of spreading. As the melanoma becomes thicker, it has a greater chance of spreading.

- Ulceration: Ulceration is a breakdown of the skin over the melanoma. Melanomas that are ulcerated tend to have a worse outlook.

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has the cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes?

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to distant lymph nodes or distant organs ? (Melanoma can spread almost anywhere in the body, but the most common sites of spread are the lungs, liver, brain, bones, and the skin or lymph nodes in other parts of the body.)

Numbers or letters after T, N, and M provide more details about each of these factors. Higher numbers mean the cancer is more advanced. Once a person’s T, N, and M categories have been determined, this information is combined in a process called stage grouping to assign an overall stage.

The staging system in the table below uses the pathologic stage (also called the surgical stage). It is determined by examining tissue removed during an operation. Sometimes, if surgery is not possible right away or at all, the cancer will be given a clinical stage instead. This is based on the results of a physical exam, biopsy, and imaging tests. The clinical stage will be used to help plan treatment. Sometimes, though, the cancer has spread further than the clinical stage estimates, and may not predict the patient’s outlook as accurately as a pathologic stage.

There are both clinical and pathologic staging systems for melanoma. Since most cancers are staged with the pathologic stage, we have included that staging system below. If your cancer has been clinically staged, it is best to talk to your doctor about your specific stage.

The table below is a simplified version of the TNM system. It is based on the most recent American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) system, effective January 2018. It’s important to know that melanoma cancer staging can be complex. If you have any questions about the stage of your cancer or what it means, please ask your doctor to explain it to you in a way you understand.

Table 2. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM Staging System

| AJCC Stage | Melanoma Stage Description | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | This stage is also known as melanoma in situ. The cancer is confined to the epidermis, the outermost skin layer (Tis). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant parts of the body (M0). | |

| 1 | The tumor is no more than 2 mm (2/25 of an inch) thick and might or might not be ulcerated (T1 or T2a). The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant parts of the body (M0) | |

| 2 | The tumor is more than 2 mm thick (T2b or T3) and may be thicker than 4 mm (T4). It might or might not be ulcerated. The cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant parts of the body (M0). | |

| 3A | The tumor is no more than 2 mm thick and might or might not be ulcerated (T1 or T2a). The cancer has spread to 1 to 3 nearby lymph nodes, but it is so small that it is only seen under the microscope (N1a or N2a). It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | |

| 3B | There is no sign of the primary tumor (T0) AND: The cancer has spread to only one nearby lymph node (N1b) OR It has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor (without reaching the nearby lymph nodes) (N1c) It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | |

| OR | ||

| The tumor is no more than 4 mm thick and might or might not be ulcerated (T1, T2, or T3a) AND: The cancer has spread to only one nearby lymph node (N1a or N1b) OR It has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor (without reaching the nearby lymph nodes) (N1c) OR It has spread to 2 or 3 nearby lymph nodes (N2a or N2b) It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | ||

| 3C | There is no sign of the primary tumor (T0) AND: The cancer has spread to 2 or more nearby lymph nodes, at least one of which could be seen or felt (N2b or N3b) OR It has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor, and it has reached the nearby lymph nodes (N2c or N3c) OR It has spread to nearby lymph nodes that are clumped together (N3b or N3c) It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | |

| OR | ||

| The tumor is no more than 4 mm thick, and might or might not be ulcerated (T1, T2, or T3a) AND: The cancer has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor, and it has reached nearby lymph nodes (N2c or N3c) OR The cancer has spread to 4 or more nearby lymph nodes (N3a or N3b), or it has spread to nearby lymph nodes that are clumped together (N3b or N3c) It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | ||

| OR | ||

| The tumor is more than 2 mm but no more than 4 mm thick and is ulcerated (T3b) OR it is thicker than 4 mm but is not ulcerated (T4a). The cancer has spread to one or more nearby lymph nodes AND/OR it has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor (N1 or higher). It has not spread to distant parts of the body. | ||

| OR | ||

| The tumor is thicker than 4 mm and is ulcerated (T4b) AND: The cancer has spread to 1 to 3 nearby lymph nodes, which are not clumped together (N1a/b or N2a/b) OR It has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor, and it might (N2c) or might not (N1c) have reached 1 nearby lymph node) It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | ||

| 3D | The tumor is thicker than 4 mm and is ulcerated (T4b) AND: The cancer has spread to 4 or more nearby lymph nodes (N3a or N3b) OR It has spread to nearby lymph nodes that are clumped together (N3b) It has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumors) or to skin lymphatic channels around the tumor, AND it has spread to at least 2 nearby lymph nodes, or to lymph nodes that are clumped together (N3c) OR It has not spread to distant parts of the body (M0). | |

| 4 | The tumor can be any thickness and might or might not be ulcerated (any T). The cancer might or might not have spread to nearby lymph nodes (any N). It has spread to distant lymph nodes or to organs such as the lungs, liver or brain (M1). | |

Footnotes: The staging system in the table above uses the pathologic stage also called the surgical stage. This is determined by examining tissue removed during an operation. Sometimes, if surgery is not possible right away (or at all), the cancer will be given a clinical stage instead. This is based on the results of physical exams, biopsies, and imaging tests. The clinical stage will be used to help plan treatment. Sometimes, though, the cancer has spread farther than the clinical stage estimates, so it may not predict a person’s outlook as accurately as a pathologic stage. If your cancer has been clinically staged, it is best to talk to your doctor about your specific stage.

[Source 10 ]Stage 0 melanoma (melanoma in situ)

Stage 0 melanoma is also known as melanoma in situ. Abnormal melanocytes are confined to the epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin (Tis). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant parts of the body (M0).

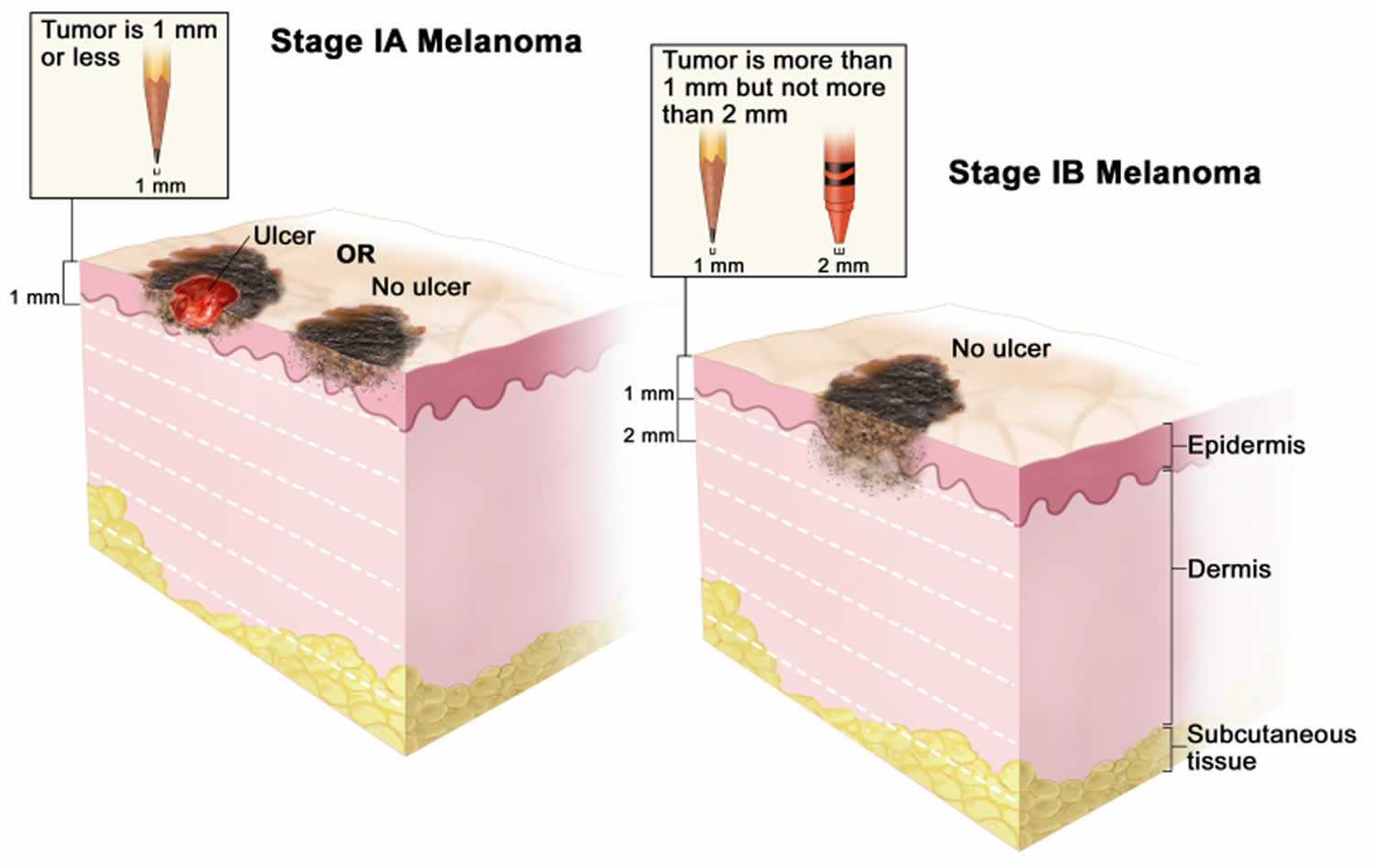

[Source 44 ]Stage 1 melanoma

Stage 1 melanoma. In stage 1A, the tumor is not more than 1 millimeter thick, with or without ulceration (a break in the skin). In stage 1B, the tumor is more than 1 mm but not more than 2 millimeters thick, without ulceration. Skin thickness is different on different parts of the body.

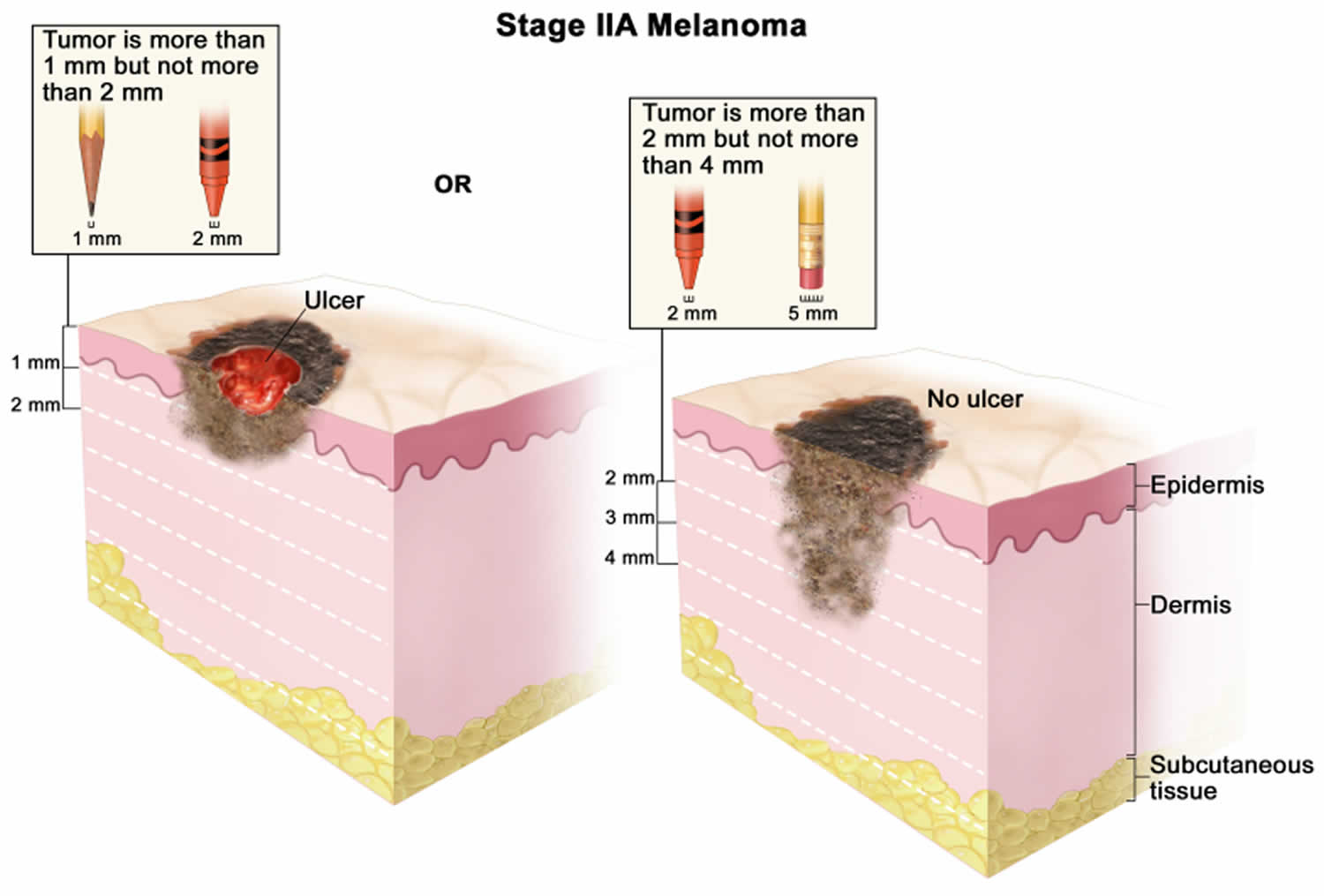

[Source 45 ]Stage 2A melanoma

In stage 2A melanoma the tumor is more than 1 mm but not more than 2 millimeters thick, with ulceration (a break in the skin); OR it is more than 2 but not more than 4 millimeters thick, without ulceration. Skin thickness is different on different parts of the body.

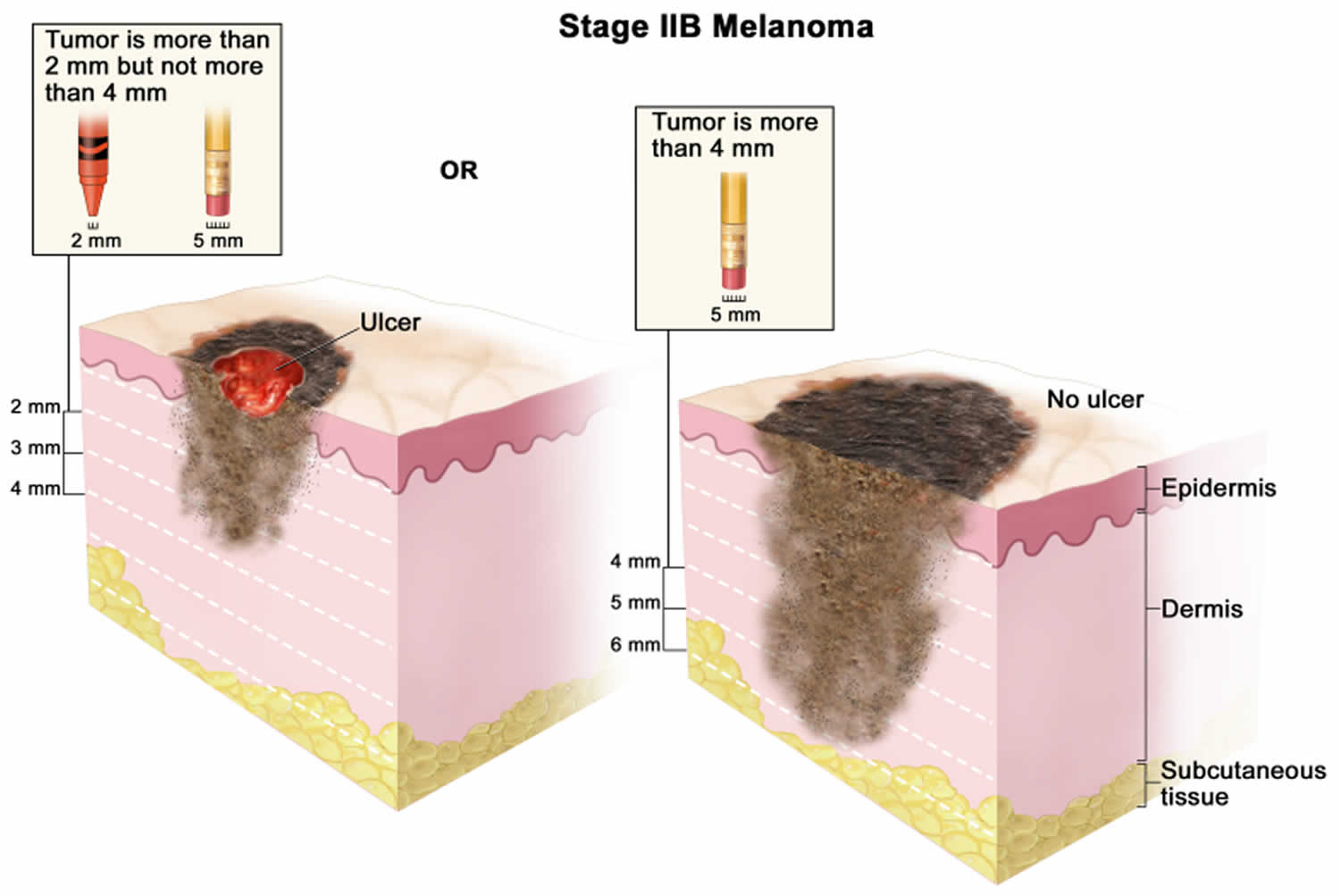

[Source 46 ]Stage 2B melanoma

In stage 2B melanoma the tumor is more than 2 mm but not more than 4 millimeters thick, with ulceration (a break in the skin); OR it is more than 4 millimeters thick, without ulceration. Skin thickness is different on different parts of the body.

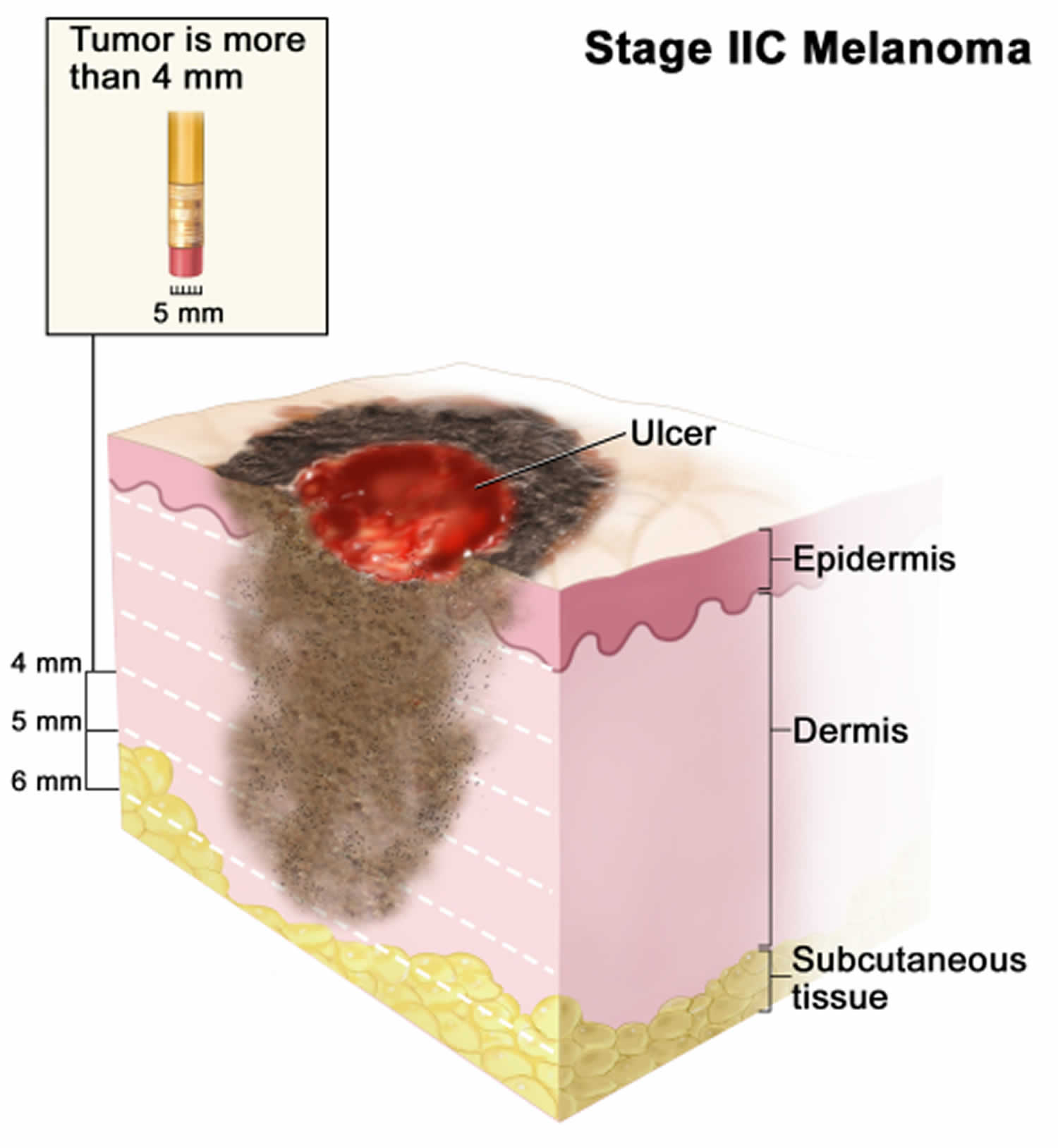

[Source 47 ]Stage 2C melanoma

In stage 2C melanoma the tumor is more than 4 millimeters thick, with ulceration (a break in the skin). Skin thickness is different on different parts of the body.

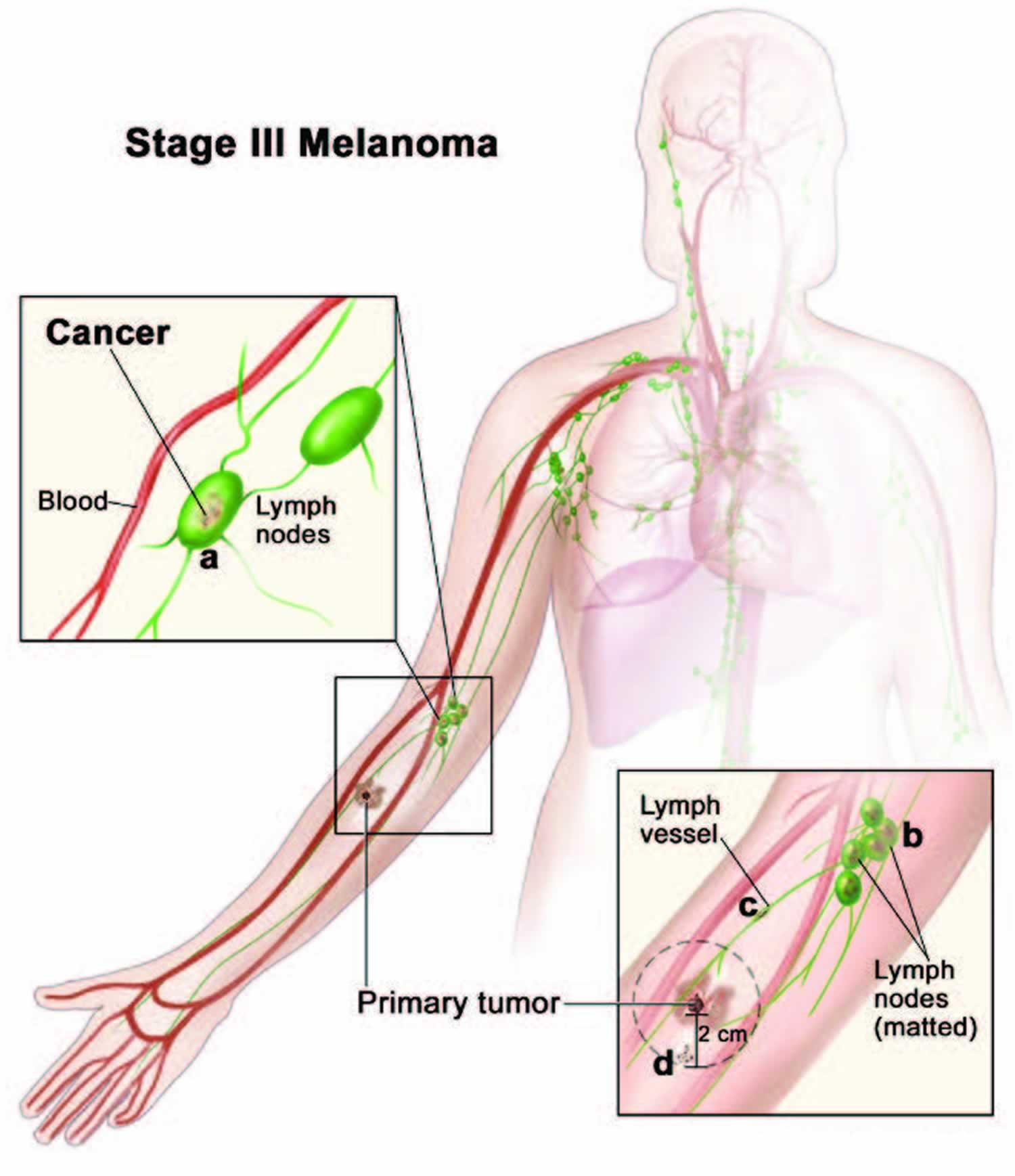

[Source 48 ]Stage 3 melanoma

Stage 3 melanoma generally means that cancer cells have spread to the lymph nodes close to where the melanoma started (the primary tumor). Or it has spread to an area between the primary tumor and the nearby lymph nodes. The tumor may be any thickness, with or without ulceration.

Stage 3 melanoma is divided into four levels – A, B, C and D depending on where the cancer has spread to, such as if there are only satellite or in-transit metastases or if there is melanoma in one or several lymph nodes.

- Stage 3A – the primary melanoma is no more than 2 mm thick. It may or may not be ulcerated. It has spread to nor more than 3 lymph nodes detected by pathology (not palpable nodes). It has not spread to distant sites.

- Stage 3B – Either the primary melanoma site cannot be found and it has spread to only one lymph node or it has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite metastasis) or lymphatic vessels, without spreading to distant sites; OR The melanoma primary is no more than 4 mm and may or may not be ulcerated. It has spread to up to three lymph nodes or to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumours) or lymphatic channels. It has not spread to distant sites.

- Stage 3C – The primary melanoma site cannot be found AND it has spread to up to 4 or more lymph nodes OR it has spread to 2 or more lymph nodes and to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite metastasis) or lymphatic vessels, without spreading to distant sites;

- OR The melanoma primary is no more than 4 mm and may or may not be ulcerated. It has spread to one or more lymph nodes or to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumours) or lymphatic channels or lymph nodes clumped together. It has not spread to distant sites;

- OR The melanoma is between 2.1 mm and 4 mm and may or may not be ulcerated AND has spread to one or more lymph nodes or has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumours) or lymphatic channels or lymph nodes clumped together. It has not spread to distant sites;

- OR The melanoma is thicker than 4 mm, is ulcerated has spread to no more than 3 lymph nodes or to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumours) or lymphatic channels. It has not spread to distant sites.

- Stage 3D – The primary melanoma is thicker than 4 mm, is ulcerated AND has spread to 4 or more lymph nodes OR has spread to very small areas of nearby skin (satellite tumours) or lymphatic channels. It has not spread to distant sites. This area is further divided into satellite or in-transit metastases. Satellite metastases are cancer cells that have spread very close to the primary tumor (within 2 cm). In-transit metastases are cancer cells that have spread further than 2 cm but before the nearest lymph node.

In some cases, the primary tumor can’t be found but there are melanoma cells in the lymph nodes or nearby area.

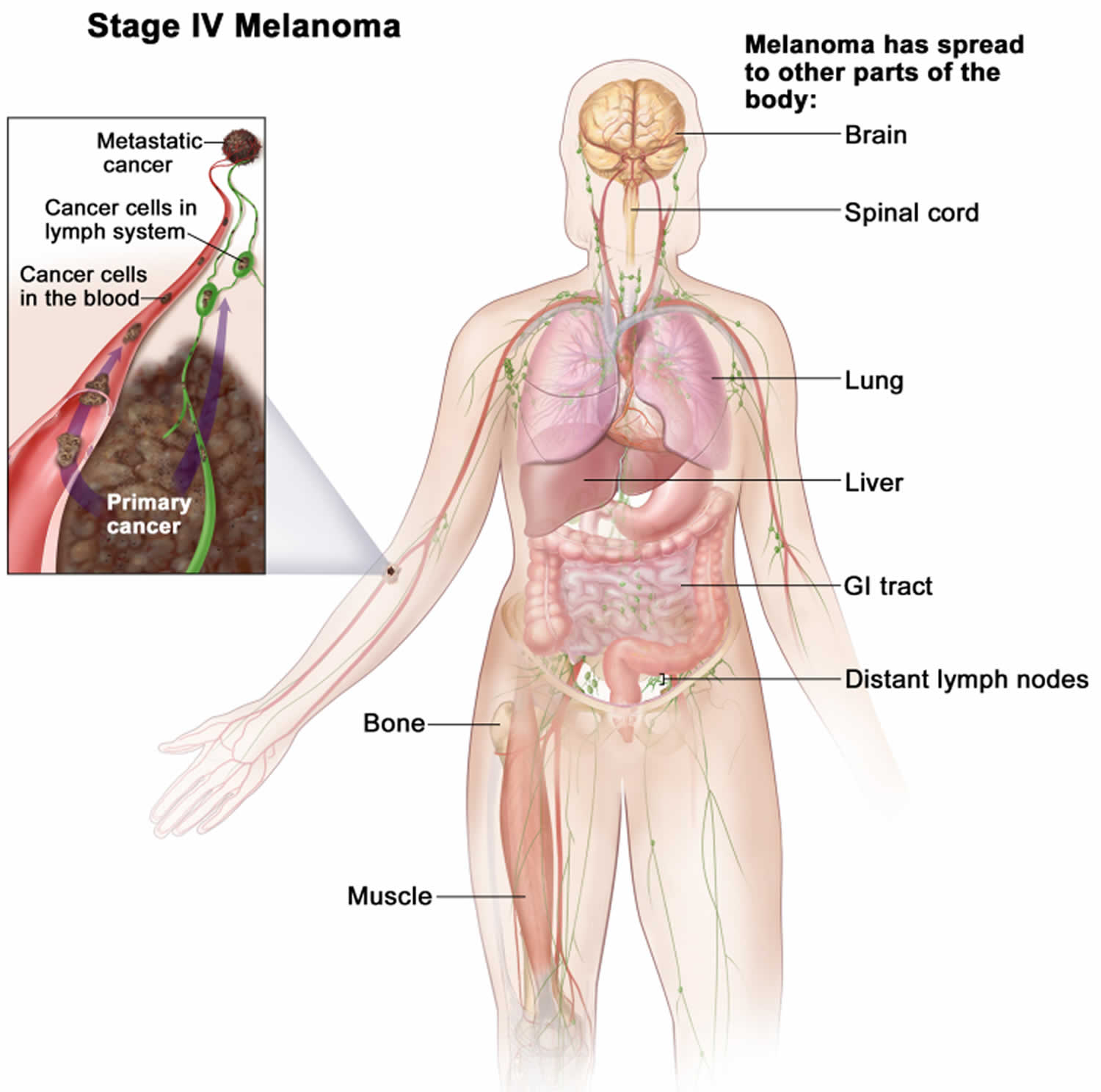

Stage 4 melanoma

Stage 4 melanoma is also known as metastatic melanoma or advanced melanoma, the cancer has spread to other parts of the body, such as the brain, spinal cord, lung, liver, gastrointestinal tract, bone, muscle, and/or distant lymph nodes. Cancer may have spread to places in the skin far away from where it first started.

[Source 49 ]Acral lentiginous melanoma treatment

Based on the stage of acral lentiginous melanoma and other factors, your treatment options might include:

- Surgery

- Immunotherapy

- Targeted Therapy

- Chemotherapy

- Radiation Therapy

Wide local excisions are the mainstay for acral lentiginous melanoma; the lesion should be completely excised with a 2-3 mm margin of normal tissue. Definitive surgical margin recommendations are based on tumor thickness at the time of biopsy. Foregoing surgical excision of in-situ lesions when surgery is not practical can be considered. Further treatment depends mainly on the Breslow thickness of the lesion.

After initial excision biopsy; the radial excision margins, measured clinically from the edge of the melanoma are shown in the table below. This may necessitate flap or graft to close the wound. In the case of acral lentiginous and subungual melanoma, this may include partial amputation of a digit. Occasionally, the pathologist will report incomplete excision of the melanoma, despite wide margins. This means further surgery or radiotherapy will be recommended to ensure the tumor has been completely removed.

- Melanoma in situ — excision margin 5 mm

- Melanoma < 1.0 mm — excision margin 1 cm

- Melanoma 1.0–2.0 mm — excision margin 1–2 cm

- Melanoma 2.0–4.0 mm — excision margin 1–2 cm

- Melanoma > 4.0 mm — excision margin 2 cm

Off label use of topical imiquimod has been studied; however, the persistence of in-situ lesions, failure to detect invasive lesions due to lack of excision, the progression of lesions, and the high cost of treatment are all potential pitfalls of this treatment 18. If metastases are detected clinically, by palpation of local lymph node beds, or by sentinel lymph node biopsy, systemic treatment with chemotherapeutic agents, targeted mutational therapy, and immune checkpoint inhibitors may be indicated. Patients who have asymptomatic high stage disease do not show a survival benefit from treatment before symptoms arise 41.

If melanoma has spread (metastasized) from the skin to other organs such as the lungs or brain, the cancer is very unlikely to be curable by surgery. Even when only 1 or 2 areas of spread are found by imaging tests such as CT or MRI scans, there are likely to be others that are too small to be found by these scans.

Surgery is sometimes done in these circumstances, but the goal is usually to try to control the cancer rather than to cure it. If 1 or even a few metastases are present and can be removed completely, this surgery may help some people live longer. Removing metastases in some places, such as the brain, might also help prevent or relieve symptoms and improve a person’s quality of life.

If you have metastatic melanoma and surgery is a treatment option, talk to your doctor and be sure you understand what the goal of the surgery would be, as well as its possible benefits and risks.

Immunotherapy for melanoma

Immunotherapy is the use of medicines to help the body’s natural defence system (immune system) to recognize and destroy melanoma cells more effectively. Your body’s disease-fighting immune system might not attack cancer because the cancer cells produce proteins that help them hide from the immune system cells. Immunotherapy works by interfering with that process. Immunotherapy is often recommended after surgery for melanoma that has spread to the lymph nodes or to other areas of the body. When melanoma can’t be removed completely with surgery, immunotherapy treatments might be injected directly into the melanoma.

You have immunotherapy if your melanoma is BRAF negative. If your melanoma is BRAF positive, you may have targeted cancer drugs or immunotherapy. Several types of immunotherapy can be used to treat melanoma.

The immunotherapy drugs for melanoma are:

- Ipilimumab (Yervoy)

- Pembrolizumab (Keytruda)

- Atezolizumab (Tecentriq)

- Nivolumab (Opdivo)

You might have a combination of drugs such as nivolumab and ipilimumab.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors

An important part of the immune system is its ability to keep itself from attacking normal cells in the body. To do this, it uses “checkpoints,” which are proteins on immune cells that need to be turned on (or off) to start an immune response. Melanoma cells sometimes use these checkpoints to avoid being attacked by the immune system. But these drugs target the checkpoint proteins, helping to restore the immune response against melanoma cells.

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and nivolumab (Opdivo) are drugs that target PD-1, a protein on immune system cells called T cells that normally help keep these cells from attacking other cells in the body. By blocking PD-1, these drugs boost the immune response against melanoma cells. This can often shrink tumors and help people live longer.

- Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) and nivolumab (Opdivo) can be used to treat melanomas:

- That can’t be removed by surgery

- That have spread to other parts of the body

- After surgery (as adjuvant treatment) for certain stage 2 or 3 melanomas to try to lower the risk of the cancer coming back

- These drugs are given as an intravenous (IV) infusion, typically every 2 to 6 weeks, depending on the drug and why it’s being given.

Atezolizumab (Tecentriq) is a drug that targets PD-L1, a protein related to PD-1 that is found on some tumor cells and immune cells. Blocking this protein can help boost the immune response against melanoma cells.

- Atezolizumab (Tecentriq) can be used along with cobimetinib and vemurafenib in people with melanoma that has the BRAF gene mutation, when the cancer can’t be removed by surgery or has spread to other parts of the body.

- Atezolizumab (Tecentriq) is given as an intravenous (IV) infusion every 2 to 4 weeks.

Ipilimumab (Yervoy) is another drug that boosts the immune response, but it has a different target. Ipilimumab (Yervoy) blocks CTLA-4, another protein on T cells that normally helps keep them in check.

- Ipilimumab (Yervoy) can be used to treat melanomas that can’t be removed by surgery or that have spread to other parts of the body. It might also be used for less advanced melanomas after surgery (as an adjuvant treatment) in some situations, to try to lower the risk of the cancer coming back.

- When used alone, this drug doesn’t seem to shrink as many tumors as the PD-1 inhibitors, and it tends to have more serious side effects, so usually one of those other drugs is used first. Another option in some situations might be to combine this drug with one of the PD-1 inhibitors. This can increase the chance of shrinking the tumors (slightly more than a PD-1 inhibitor alone), but it can also increase the risk of side effects.

- Ipilimumab (Yervoy) is given as an intravenous (IV) infusion, usually once every 3 weeks for 4 treatments (although it may be given for longer when used as an adjuvant treatment).

Relatlimab targets LAG-3, another checkpoint protein on certain immune cells that normally helps keep the immune system in check.

- Relatlimab is given along with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab (in a combination known as Opdualag). It can be used to treat melanomas that can’t be removed by surgery or that have spread to other parts of the body.

- Relatlimab is given as an intravenous (IV) infusion, typically once every 4 weeks.

Side effects of immune checkpoint inhibitors

- Some of the more common side effects of these drugs can include fatigue, cough, nausea, skin rash, poor appetite, constipation, joint pain, and diarrhea.

- Other, more serious side effects occur less often.

- Infusion reactions: Some people might have an infusion reaction while getting these drugs. This is like an allergic reaction, and can include fever, chills, flushing of the face, rash, itchy skin, feeling dizzy, wheezing, and trouble breathing. It’s important to tell your doctor or nurse right away if you have any of these symptoms while getting these drugs.

- Autoimmune reactions: These drugs remove one of the safeguards on the body’s immune system. Sometimes the immune system responds by attacking other parts of the body, which can cause serious or even life-threatening problems in the lungs, intestines, liver, hormone-making glands, kidneys, or other organs.

It’s very important to report any new side effects to someone on your health care team as soon as possible. If serious side effects do occur, treatment may need to be stopped and you might be given high doses of corticosteroids to suppress your immune system.

Talimogene laherparepvec (oncolytic virus therapy)

Doctors might use another type of immunotherapy called talimogene laherparepvec (T- VEC or Imlygic) also known as oncolytic virus therapy, which they inject directly into the melanomas in the skin or lymph nodes that can’t be removed with surgery. Talimogene laherparepvec (T- VEC or Imlygic) is a weakened form of the cold sore virus. The changed virus grows in the cancer cells and destroys them. Talimogene laherparepvec (T- VEC or Imlygic) also works by helping the immune system to recognize and attack cancer cells.

You might have T-VEC for melanoma that can’t be removed with surgery or has spread to certain areas of the body such as the lymph nodes or skin. It treats the tumor it is injected into but may also have an effect on tumors nearby. The virus is injected directly into the tumors, typically every 2 weeks. This treatment can sometimes shrink these tumors, and might also shrink tumors in other parts of the body.

Some of the common side effects include:

- flu-like symptoms including a high temperature, sore throat, shivering and muscle aches

- high blood pressure

- headaches and dizziness

- bleeding

- tummy pain

- diarrhoea and constipation

- feeling or being sick

- skin problems such as a rash

- tiredness (fatigue)

Doctors used to use two other types of immunotherapy drugs called interferon and interleukin-2 (IL-2) to treat melanoma. They don’t use these drugs very often any more.

Interleukin-2 (IL-2)

Interleukins are proteins that certain cells in the body make to boost the immune system in a general way. Lab-made versions of interleukin-2 (IL-2) are sometimes used to treat melanoma. They are given as intravenous (IV) infusions, at least at first. Some patients or caregivers may be able to learn how to give injections under the skin at home.

- For advanced melanomas: Interleukin-2 (IL-2) can sometimes shrink advanced melanomas when used alone. It is not used as much as in the past, because the immune checkpoint inhibitors are more likely to help people and tend to have fewer side effects. But interleukin-2 (IL-2) might be an option if these drugs are no longer working.

- For some earlier-stage melanomas: Melanomas that have reached the nearby lymph nodes are more likely to come back in another part of the body, even if all of the cancer is thought to have been removed. Interleukin-2 (IL-2) can sometimes be injected into the tumors (known as intralesional therapy) to try to prevent this. Side effects are similar but tend to be milder when IL-2 is injected directly into the tumor.

When deciding whether to use interleukin-2 (IL-2), patients and their doctors need to take into account the potential benefits and side effects of this treatment.

Side effects of interleukin-2 (IL-2) can include flu-like symptoms such as fever, chills, aches, severe tiredness, drowsiness, and low blood cell counts. In high doses, interleukin-2 (IL-2) can cause fluid to build up in the body so that the person swells up and can feel quite sick. Because of this and other possible serious side effects, high-dose interleukin-2 (IL-2) is given only in the hospital, in centers that have experience with this type of treatment.

Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine

Bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) is a germ related to the one that causes tuberculosis. BCG doesn’t cause serious disease in humans, but it does activate the immune system. The BCG vaccine can be used to help treat stage 3 melanomas by injecting it directly into tumors, although it isn’t used very often.

Imiquimod cream

Imiquimod (Zyclara) is a drug that is put on the skin as a cream. It stimulates a local immune response against skin cancer cells. For very early (stage 0) melanomas in sensitive areas on the face, some doctors may use imiquimod if surgery might be disfiguring. It might also be an option for some melanomas that have spread along the skin.

The cream is usually applied 2 to 5 times a week for around 3 months. Some people have serious skin reactions to this drug. Imiquimod is not used for more advanced melanomas.

Targeted therapy for melanoma

Targeted therapy drugs target parts of melanoma cells that make them different from normal cells. Targeted drugs work differently from standard chemotherapy drugs, which basically attack any quickly dividing cells. Targeted drugs can be very helpful in treating melanomas that have certain gene changes.

Drugs that target cells with BRAF gene changes

About half of all melanomas have changes (mutations) in the BRAF gene. Melanoma cells with these changes make an altered BRAF protein that helps them grow. Some drugs target this and related proteins, such as the MEK proteins. If you have melanoma that has spread beyond the skin, a biopsy sample of it will likely be tested to see if the cancer cells have a BRAF mutation. Drugs that target the BRAF protein (BRAF inhibitors) or the MEK proteins (MEK inhibitors) aren’t likely to work on melanomas that have a normal BRAF gene.

Most often, if a person has a BRAF mutation and needs targeted therapy, they will get both a BRAF inhibitor and a MEK inhibitor, as combining these drugs often works better than either one alone.

- BRAF inhibitors. Vemurafenib (Zelboraf), dabrafenib (Tafinlar), and encorafenib (Braftovi) are drugs that attack the BRAF protein directly.

- These drugs can shrink or slow the growth of tumors in some people whose melanoma has spread or can’t be removed completely.

- Dabrafenib can also be used (along with the MEK inhibitor trametinib) after surgery in people with stage 3 melanoma, where it can help lower the risk of the cancer coming back.

- These drugs are taken as pills or capsules, once or twice a day.

- Common side effects can include skin thickening, rash, itching, sensitivity to the sun, headache, fever, joint pain, fatigue, hair loss, and nausea. Less common but serious side effects can include heart rhythm problems, liver problems, kidney failure, severe allergic reactions, severe skin or eye problems, bleeding, and increased blood sugar levels. Some people treated with these drugs develop new squamous cell skin cancers. These cancers are usually less serious than melanoma and can be treated by removing them. Still, your doctor will want to check your skin often during treatment and for several months afterward. You should also let your doctor know right away if you notice any new growths or abnormal areas on your skin.

- MEK inhibitors. The MEK gene works together with the BRAF gene, so drugs that block MEK proteins can also help treat melanomas with BRAF gene changes. MEK inhibitors include trametinib (Mekinist), cobimetinib (Cotellic), and binimetinib (Mektovi).

- These drugs can be used to treat melanoma that has spread or can’t be removed completely.

- Trametinib can also be used along with dabrafenib after surgery in people with stage 3 melanoma, where it can help lower the risk of the cancer coming back.

- Again, the most common approach is to combine a MEK inhibitor with a BRAF inhibitor. This seems to shrink tumors for longer periods of time than using either type of drug alone.

- Some side effects (such as the development of other skin cancers) are actually less common with the combination.

- MEK inhibitors are pills taken once or twice a day.

- Common side effects can include rash, nausea, diarrhea, swelling, and sensitivity to sunlight. Rare but serious side effects can include heart lung, or liver damage; bleeding or blood clots; vision problems; muscle damage; and skin infections.

- Drugs that target cells with C-KIT gene changes. A small portion of melanomas have changes in the C-KIT gene that help them grow. These changes are more common in melanomas that start in certain parts of the body:

- On the palms of the hands, soles of the feet, or under the nails (known as acral melanomas)

- Inside the mouth or other mucosal (wet) areas

- In areas that get chronic sun exposure

- Some targeted drugs, such as imatinib (Gleevec) and nilotinib (Tasigna), can affect cells with changes in C-KIT. If you have an advanced melanoma that started in one of these places, your doctor may test your melanoma cells for changes in the C-KIT gene, which might mean that one of these drugs could be helpful.

Drugs that target different gene changes are also being studied in clinical trials.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy (chemo) uses drugs that kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy might be used to treat advanced melanoma after other treatments have been tried, but it’s not often used as the first treatment because newer forms of immunotherapy and targeted drugs are typically more effective. Chemo is usually not as helpful for melanoma as it is for some other types of cancer, but it can shrink tumors in some people.

Several chemo drugs can be used to treat melanoma:

- Dacarbazine (also called DTIC)

- Temozolomide

- Nab-paclitaxel

- Paclitaxel

- Cisplatin

- Carboplatin

Some of these drugs are given alone, while others are more often combined with other drugs. It’s not clear if using combinations of drugs is more helpful than using a single drug, but it can add to the side effects.

Doctors give chemo in cycles, with each period of treatment followed by a rest period to give the body time to recover. Each chemo cycle typically lasts for a few weeks.

Isolated limb perfusion (ILP) and isolated limb infusion (ILI)

These are ways of giving chemotherapy that are sometimes used to treat melanoma that is confined to an arm or leg but that can’t be removed with surgery. The idea with this approach is to keep the chemo in the limb and not allow it to reach other parts of the body, where it could cause more side effects.

This is done during a surgical procedure. The blood flow of the arm or leg is separated from the rest of the body, and a high dose of chemotherapy is circulated through the limb for a short period of time. This lets doctors give high doses to the area of the tumor without exposing other parts of the body to these doses.

To do this, a tube is placed into the artery that feeds blood into the limb, and a second tube is placed into the vein that drains blood from it.

- For isolated limb perfusion (ILP), the artery and vein are first surgically separated from the circulation to the rest of the body, and are then hooked up to tubes going to a special machine in the operating room.

- For isolated limb infusion (ILI), long tubes (catheters) are inserted through the skin and into the artery and vein. This method is less complex and takes less time, and it might not require general anesthesia (where you are in a deep sleep).

In either case, a tourniquet is tied around the limb to help make sure the chemo doesn’t enter the rest of the body. Chemotherapy (usually with a drug called melphalan) is infused into the blood in the limb through the artery. This is done by the machine in isolated limb perfusion (ILP), and by using a syringe in isolated limb infusion (ILI). During the treatment session, the blood exits the limb through the tube in the vein, the chemo is added, and then the blood is returned back to the limb through the tube in the artery. During isolated limb perfusion (ILP), the drug can also be heated by the machine to help the chemo work better. By the end of the treatment the drug is washed out of the limb, and the tubes are removed (and for isolated limb perfusion (ILP) the blood vessels are stitched back together) so that the circulation is returned to normal.

Chemo drugs can cause side effects. These depend on the type and dose of drugs given and how long they are used. The side effects of chemo can include:

- Hair loss

- Mouth sores

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diarrhea or constipation

- Increased risk of infection (from having too few white blood cells)

- Easy bruising or bleeding (from having too few blood platelets)

- Fatigue (from having too few red blood cells)

These side effects usually go away once treatment is finished. There are often ways to lessen side effects. For example, drugs can help prevent or reduce nausea and vomiting. Be sure to ask your doctor or nurse about drugs to help reduce side effects.

Some chemo drugs can have other side effects. For example, some drugs can damage nerves, which can lead to symptoms (mainly in the hands and feet) such as pain, burning or tingling sensations, sensitivity to cold or heat, or weakness. This condition is called peripheral neuropathy. It usually goes away once treatment is stopped, but for some people it can last a long time.

Be sure to talk with your cancer care team about what to expect in terms of side effects. While you are getting chemo, report any side effects to your medical team so that they can be treated promptly. In some cases, the doses of chemo may need to be reduced or treatment may need to be delayed or stopped to prevent side effects from getting worse.

Radiation treatments

Radiation therapy also known as radiotherapy uses high-energy rays (such as x-rays) or particles to kill cancer cells. Radiation therapy is not needed for most people with melanoma on the skin, although it might be useful in certain situations:

- Radiation therapy might be an option to treat very early stage melanomas, if surgery can’t be done for some reason.

- Radiation can also be used after surgery for an uncommon type of melanoma known as desmoplastic melanoma.

- Sometimes, radiation is given after surgery in the area where lymph nodes were removed, especially if many of the nodes contained cancer cells. This is to try to lower the chance that the cancer will come back.

- Radiation can be used to treat melanoma that has come back after surgery, either in the skin or lymph nodes, or to help treat distant spread of the disease.

- Radiation therapy is often used to relieve symptoms caused by the spread of the melanoma, especially to the brain or bones. Treatment with the goal of relieving symptoms is called palliative therapy. Palliative radiation therapy is not expected to cure the cancer, but it might help shrink it or slow its growth for a time to help control some of the symptoms.

The type of radiation most often used to treat melanoma, known as external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), focuses radiation from a source outside of the body on the cancer. Treatment is much like getting an x-ray, but the radiation is stronger. The procedure itself is painless. Each treatment lasts only a few minutes, although the setup time – getting you into place for treatment – usually takes longer. The treatment schedule can vary based on the goal of treatment and where the melanoma is. Before treatments start, your radiation team will take careful measurements to find the correct angles for aiming the radiation beams and the proper dose of radiation. This planning session is called simulation.

Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) is a type of radiation therapy that can sometimes be used for tumors that have spread to the brain. Despite the name, there is no actual surgery. High doses of radiation are aimed precisely at the tumor(s) in one or more treatment sessions. There are 2 main ways to give stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS):

- In one version, a machine called a Gamma Knife® focuses about 200 thin beams of radiation on the tumor from different angles over a few minutes to hours. The head is kept in the same position by placing it in a rigid frame.

- In another version, a linear accelerator (a machine that creates radiation) that is controlled by a computer moves around the head to deliver radiation to the tumor from many different angles over a few minutes. The head is kept in place with a head frame or a plastic face mask.

These treatments can be repeated if needed.

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT) is similar to stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) (using a linear accelerator), but it can be used to treat tumors in other parts of the body.

Side effects of radiation therapy are usually limited to the area getting radiation. Common side effects can include:

- Sunburn-like skin problems

- Changes in skin color

- Hair loss where the radiation enters the body

- Fatigue

- Nausea (if radiation is aimed at the abdomen)

Often these go away after treatment.

Radiation therapy to the brain can sometimes cause memory loss, headaches, trouble thinking, or reduced sexual desire. Usually these symptoms are minor compared with those caused by a tumor in the brain, but they might still affect your quality of life.

Surgery for metastatic melanoma

If melanoma has spread (metastasized) from the skin to other organs such as the lungs or brain, the cancer is very unlikely to be curable by surgery. Even when only 1 or 2 areas of spread are found by imaging tests such as CT or MRI scans, there are likely to be others that are too small to be found by these scans.

Surgery is sometimes done in these circumstances, but the goal is usually to try to control the cancer rather than to cure it. If 1 or even a few metastases are present and can be removed completely, this surgery may help some people live longer. Removing metastases in some places, such as the brain, might also help prevent or relieve symptoms and improve a person’s quality of life.

If you have metastatic melanoma and your doctor suggests surgery as a treatment option, be sure you understand what the goal of the surgery would be, as well as its possible benefits and risks.

Clinical trials

Clinical trials are research studies that test new drugs or other treatments in people. They compare standard treatments with others that may be better.

If you would like to learn more about clinical trials that might be right for you, start by asking your doctor if your clinic or hospital conducts clinical trials.

Clinical trials are one way to get the newest cancer treatment. They are the best way for doctors to find better ways to treat cancer. If your doctor can find one that’s studying the kind of cancer you have, it’s up to you whether to take part. And if you do sign up for a clinical trial, you can always stop at any time.

Acral lentiginous melanoma prognosis

Acral lentiginous melanoma prognosis depends on the stage of the melanoma when it was diagnosed. This means how deeply the melanoma has grown into the skin and whether it has spread. Survival is better for women than it is for men. Scientists don’t know exactly why this is. It may be because women are more likely to see a doctor about their melanoma at an earlier stage. Age can affect outlook and younger people have a better prognosis than older people. Your outlook may also be affected by where the melanoma is in the body.

In two studies 43, 14, positive sentinel lymph nodes were the strongest predictor of disease recurrence and death from melanoma. (A sentinel lymph node is defined as the first lymph node to which cancer cells are most likely to spread from a primary tumor.) Compared to cutaneous malignant melanoma at the same stage and depth, acral lentiginous melanoma has lower respective survival rates 16 with few studies finding that survival rates are similar 50. Acral lentiginous melanomas often present at a more advanced stage, which is thought to be multifactorial in cause. Contributing to this is difficulty in observation of the soles of the feet by the elderly, lack of knowledge in minority populations about their risk for melanoma, decreased access to care, and other cultural factors 18.

Acral lentiginous melanoma in situ is not dangerous; it only becomes potentially life threatening if an invasive melanoma develops within it. The risk of spread from invasive melanoma depends on several factors, but the main one is the measured thickness of the melanoma at the time it was surgically removed.

The Melanoma Guidelines report that metastases are rare for melanomas <0.75mm and the risk for tumors 0.75–1 mm thick is about 5%. The risk steadily increases with thickness so that melanomas >4 mm; result in a 10-year survival of around 50%, according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) statistics.

Survival rates can give you an idea of what percentage of people with the same type and stage of cancer are still alive a certain amount of time (usually 5 years) after they were diagnosed. They can’t tell you how long you will live, but they may help give you a better understanding of how likely it is that your treatment will be successful. A relative survival rate compares people with the same type and stage of cancer to people in the overall population. For example, if the 5-year relative survival rate for a specific stage of melanoma of the skin is 93.7%, it means that people who have that cancer are, on average, about 93.7% as likely as people who don’t have that cancer to live for at least 5 years after being diagnosed 51.

The National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database tracks 5-year relative survival rates for melanoma skin cancer in the United States, based on how far the cancer has spread 51. The SEER database, however, does not group cancers by American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM Staging System stages (stage 1, stage 2, stage 3, etc.). Instead, it groups cancers into localized, regional, and distant stages: