Acute otitis media

Acute otitis media is a bacterial or viral infection of the middle ear, usually accompanying an upper respiratory infection. Symptoms include otalgia (ear pain), often with systemic symptoms (eg, fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea), especially in the very young children. Diagnosis is based on otoscopy. Treatment is with analgesics and sometimes antibiotics.

Although acute otitis media can occur at any age, it is most common between ages 3 months and 3 years. At this age, the eustachian tube is structurally and functionally immature—the angle of the eustachian tube is more horizontal, and the angle of the tensor veli palatini muscle and the cartilaginous eustachian tube renders the opening mechanism less efficient. Anything that causes the eustachian tubes to become swollen or blocked makes more fluid build up in the middle ear behind the eardrum.

Otitis media is less common in adults than in children, though it is more common in specific sub-populations such as those with a childhood history of recurrent otitis media, cleft palate, immunodeficiency or immunocompromised status, and others 1.

The cause of acute otitis media may be viral or bacterial. Viral infections are often complicated by secondary bacterial infection. In neonates, Gram-negative enteric bacilli, particularly Escherichia coli, and Staphylococcus aureus cause acute otitis media. In older infants and children < 14 years, the most common organisms are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Moraxella (Branhamella) catarrhalis, and nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae; less common causes are group A β-hemolytic streptococci and Staphylococcus aureus. In patients > 14 years, Streptococcus pneumoniae, group A β-hemolytic streptococci, and Staphylococcus aureus are most common, followed by Haemophilus influenzae. The most common viral pathogens of otitis media include the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), coronaviruses, influenza viruses, adenoviruses, human metapneumovirus, and picornaviruses 2.

Because most ear infections often clear up on their own without antibiotic treatment, treatment may begin with managing pain and monitoring the problem. Sometimes, antibiotics are used to clear the infection. However, what’s best for your child depends on many factors, including your child’s age and the severity of symptoms. Some people are prone to having multiple ear infections. This can cause hearing problems and other serious complications.

Your child’s doctor is more likely to prescribe antibiotics if your child:

- Is under age 2

- Has a fever

- Appears sick

- Does not improve in 24 to 48 hours

All children younger than 6 months with a fever or symptoms of an ear infection should see a doctor. Children who are older than 6 months may be watched at home if they DO NOT have:

- A fever higher than 102°F (38.9°C)

- More severe pain or other symptoms

- Other medical problems

Let your child’s doctor know right away if your child is younger than 6 months has a fever, even if your child doesn’t have other symptoms.

See your child’s doctor if:

- Pain, fever, or irritability do not improve within 24 to 48 hours

- At the start, the child seems sicker than you would expect from an ear infection

- Your child has a high fever or severe pain

- Severe pain suddenly stops — this may indicate a ruptured eardrum

- Symptoms get worse

- New symptoms appear, especially severe headache, dizziness, swelling around the ear, or twitching of the face muscles

If there is no improvement or if symptoms get worse, schedule an appointment with your health care provider to determine whether antibiotics are needed.

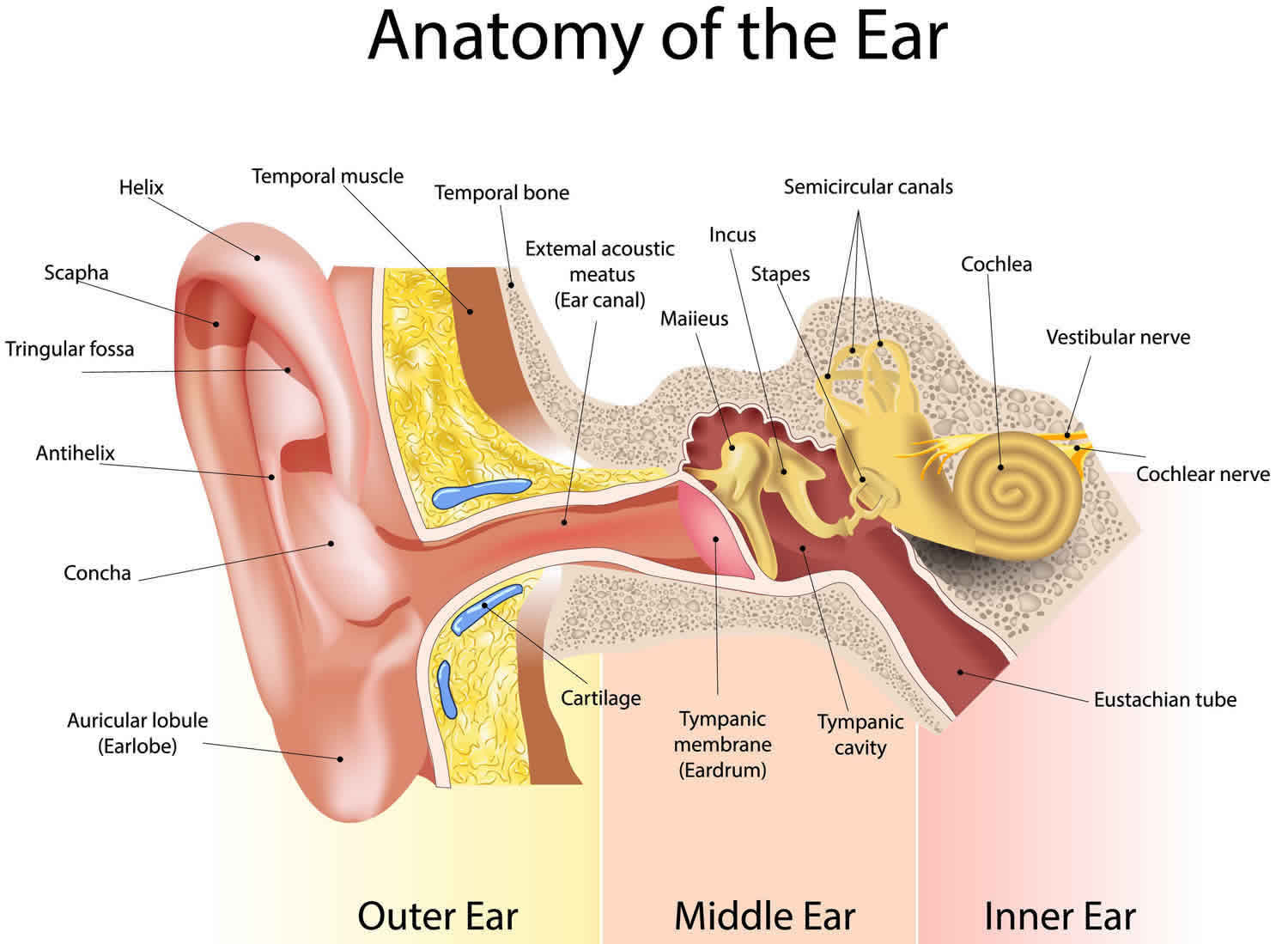

Figure 1. Ear anatomy

Figure 2. Middle ear and auditory ossicles

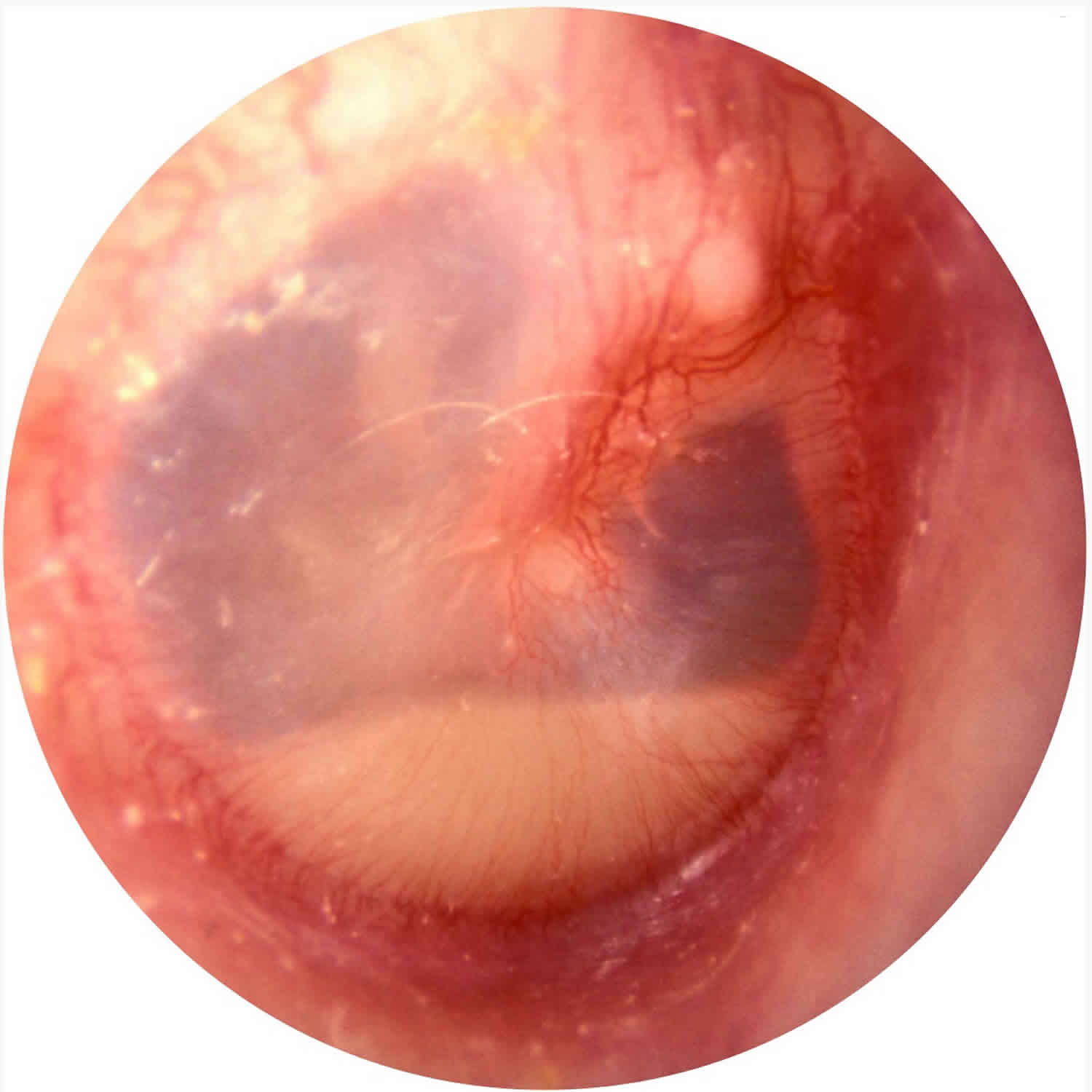

Footnote: Otoscopic view of acute otitis media. Erythema and bulging of the tympanic membrane with loss of normal landmarks are noted.

Acute otitis media causes

Acute otitis media usually starts with a cold or a sore throat caused by bacteria or a virus. The infection spreads through the back of the throat to the middle ear, to which it is connected by the eustachian tube (also called auditory tube). The infection in the middle ear causes swelling and fluid build-up, which puts pressure on the eardrum.

Acute otitis media are common in infants and children because the eustachian tubes are easily clogged. Acute otitis media can also occur in adults, although they are less common than in children.

The eustachian tube runs from the middle of each ear to the back of the throat (see Figures 1 and 2). Normally, the eustachian tube drains fluid that is made in the middle ear. If the eustachian tube gets blocked, fluid can build up. This can lead to infection.

Anything that causes the eustachian tubes to become swollen or blocked makes more fluid build up in the middle ear behind the eardrum. Some causes are:

- Allergies

- Colds and sinus infections

- Excess mucus and saliva produced during teething

- Infected or overgrown adenoids (lymph tissue in the upper part of the throat)

- Tobacco smoke

Acute otitis media are also more likely in children who spend a lot of time drinking from a sippy cup or bottle while lying on their back. Getting water in the ears will not cause an acute ear infection, unless the eardrum has a hole in it.

Usually, acute otitis media is a complication of eustachian tube dysfunction that occurred during an acute viral upper respiratory tract infection. Bacteria can be isolated from middle ear fluid cultures in 50% to 90% of cases of acute otitis media and serous otitis media 3. Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae (nontypable), and Moraxella catarrhalis are the most common organisms 4. Haemophilus influenzae has become the most prevalent organism among children with severe or refractory acute otitis media following the introduction of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine 5. The most common viral pathogens of otitis media include the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), coronaviruses, influenza viruses, adenoviruses, human metapneumovirus, and picornaviruses 2.

Acute otitis media most often occur in the winter. You cannot catch an ear infection from someone else. But a cold that spreads among children may cause some of them to get ear infections.

Adults

There is little published information to guide the management of otitis media in adults. Adults with new-onset unilateral, recurrent acute otitis media (greater than two episodes per year) or persistent otitis media with effusion (greater than six weeks) should receive additional evaluation to rule out a serious underlying condition, such as mechanical obstruction, which in rare cases is caused by nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Isolated acute otitis media or transient otitis media with effusion may be caused by eustachian tube dysfunction from a viral upper respiratory tract infection; however, adults with recurrent acute otitis media or persistent otitis media with effusion should be referred to an otolaryngologist.

Risk factors for acute otitis media

The presence of smoking in the household is a significant risk factor for acute otitis media. Other risk factors include a strong family history of otitis media, bottle feeding (ie, instead of breastfeeding), and attending a day care center.

Risk factors for acute otitis media 6:

- Age (younger). Children between the ages of 6 months and 2 years are more susceptible to ear infections because of the size and shape of their eustachian tubes and because their immune systems are still developing.

- Allergies. Ear infections are most common during the fall and winter. People with seasonal allergies may have a greater risk of ear infections when pollen counts are high.

- Craniofacial abnormalities e.g., cleft palate. Differences in the bone structure and muscles in children who have cleft palates may make it more difficult for the eustachian tube to drain.

- Exposure to environmental smoke or other respiratory irritants. Exposure to tobacco smoke or high levels of air pollution can increase the risk of ear infections.

- Attending day care (especially centers with more than 6 children). Children cared for in group settings are more likely to get colds and ear infections than are children who stay home. The children in group settings are exposed to more infections, such as the common cold.

- Family history of recurrent acute otitis media

- Gastroesophageal reflux

- Immunodeficiency

- No breastfeeding. Babies who drink from a bottle, especially while lying down, tend to have more ear infections than do babies who are breast-fed.

- Pacifier use

- Upper respiratory tract infections (URTI)

- Changes in altitude or climate

- Cold climate

- Recent ear infection

- Recent illness of any type (because illness lowers the body’s resistance to infection)

- Alaska Native heritage. Ear infections are more common among Alaska Natives.

- Decreased immunity due to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), diabetes, and other immuno-deficiencies 7

- Lower socioeconomic status

- Ciliary dysfunction

- Cochlear implants

- Vitamin A deficiency

Acute otitis media prevention

Routine childhood vaccination against pneumococci (with pneumococcal conjugate vaccine), Haemophilus influenzae type B, and influenza decreases the incidence of acute otitis media. Infants should not sleep with a bottle, and elimination of household smoking may decrease incidence. Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended for children who have recurrent episodes of acute otitis media.

Recurrent acute otitis media and recurrent secretory otitis media may be prevented by the insertion of tympanostomy tubes.

You can reduce your child’s risk of ear infections with the following measures:

- Wash hands and toys often. Teach your children to wash their hands frequently and thoroughly and to not share eating and drinking utensils. Teach your children to cough or sneeze into their elbow. If possible, limit the time your child spends in group child care. A child care setting with fewer children may help. Try to keep your child home from child care or school when ill.

- If possible, choose a day care that has 6 or fewer children. This can reduce your child’s chances of getting a cold or other infection, and lead to fewer ear infections.

- DO NOT use pacifiers.

- Breastfeed — This makes a child much less prone to ear infections. Breast milk contains antibodies that may offer protection from ear infections. If possible, breast-feed your baby for at least six months. If you are bottle feeding, hold your infant in an upright, seated position. Avoid propping a bottle in your baby’s mouth while he or she is lying down. Don’t put bottles in the crib with your baby.

- DO NOT expose your child to secondhand smoke. Make sure that no one smokes in your home. Away from home, stay in smoke-free environments.

- Make sure your child’s immunizations are up to date. The pneumococcal vaccine prevents infections from the bacteria that most commonly cause acute ear infections and many respiratory infections.

- DO NOT overuse antibiotics. Doing so can lead to antibiotic resistance.

Acute otitis media symptoms

The usual initial symptom is earache, often with hearing loss.

In infants, often the main sign of an acute otitis media is acting irritable, cranky or crying that cannot be soothed. Many infants and children with an acute ear infection have a fever or trouble sleeping. Fever, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea often occur in young children. Tugging on the ear is not always a sign that the child has an ear infection.

Acute otitis media signs and symptoms common in children include:

- Ear pain, especially when lying down

- Tugging or pulling at an ear

- Trouble sleeping

- Crying more than usual

- Fussiness

- Trouble hearing or responding to sounds

- Loss of balance

- Fever of 100 °F (38 °C) or higher

- Drainage of fluid from the ear

- Headache

- Loss of appetite

Symptoms of an acute otitis media in older children or adults include:

- Ear pain or earache

- Fullness in the ear

- Feeling of general illness

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Hearing loss in the affected ear

Sudden drainage of yellow or green fluid from the ear may mean the eardrum has ruptured.

All acute ear infections involve fluid behind the eardrum. At home, you can use an electronic ear monitor to check for this fluid. You can buy this device at a drugstore. You still need to see a health care provider to confirm an ear infection.

Otoscopic examination can show a bulging, erythematous tympanic membrane (eardrum) with indistinct landmarks and displacement of the light reflex. Air insufflation (pneumatic otoscopy) shows poor mobility of the eardrum. Spontaneous perforation of the eardrum (tympanic membrane) causes serosanguineous or purulent ear discharge (otorrhea).

Severe headache, confusion, or focal neurologic signs may occur with intracranial spread of infection. Facial paralysis or vertigo suggests local extension to the fallopian canal or labyrinth.

Acute otitis media complications

Most midlle ear infections don’t cause long-term complications. In rare cases, bacterial middle ear infection spreads locally, resulting in acute mastoiditis (an infection of the bones around the skull), petrositis, or labyrinthitis. Intracranial spread is extremely rare and usually causes meningitis, but brain abscess, subdural empyema, epidural abscess, lateral sinus thrombosis, or otitic hydrocephalus may occur. Even with antibiotic treatment, intracranial complications are slow to resolve, especially in immunocompromised patients.

Middle ear infections that happen again and again can lead to serious complications:

- Impaired hearing. Mild hearing loss that comes and goes is fairly common with an ear infection, but it usually gets better after the infection clears. Ear infections that happen again and again, or fluid in the middle ear, may lead to more-significant hearing loss. If there is some permanent damage to the eardrum or other middle ear structures, permanent hearing loss may occur.

- Speech or developmental delays. If hearing is temporarily or permanently impaired in infants and toddlers, they may experience delays in speech, social and developmental skills.

- Spread of infection. Untreated infections or infections that don’t respond well to treatment can spread to nearby tissues. Infection of the mastoid, the bony protrusion behind the ear, is called mastoiditis. This infection can result in damage to the bone and the formation of pus-filled cysts. Rarely, serious middle ear infections spread to other tissues in the skull, including the brain or the membranes surrounding the brain (meningitis).

- Tearing of the eardrum. Most eardrum tears heal within 72 hours. In some cases, surgical repair is needed.

Acute otitis media diagnosis

Diagnosis of acute otitis media usually is clinical, based on the presence of acute (within 48 hours) onset of pain, bulging of the tympanic membrane and, particularly in children, the presence of signs of middle ear effusion on pneumatic otoscopy. With the pneumatic otoscope, your doctor gently puffs air against the eardrum. Normally, this puff of air would cause the eardrum to move. If the middle ear is filled with fluid, your doctor will observe little to no movement of the eardrum. Except for fluid obtained during myringotomy, cultures are not generally done.

Your doctor may perform other tests if there is any doubt about a diagnosis, if the condition hasn’t responded to previous treatments, or if there are other long-term or serious problems.

- Tympanometry. This test measures the movement of the eardrum. The device, which seals off the ear canal, adjusts air pressure in the canal, which causes the eardrum to move. The device measures how well the eardrum moves and provides an indirect measure of pressure within the middle ear.

- Acoustic reflectometry. This test measures how much sound is reflected back from the eardrum — an indirect measure of fluids in the middle ear. Normally, the eardrum absorbs most of the sound. However, the more pressure there is from fluid in the middle ear, the more sound the eardrum will reflect.

- Tympanocentesis. Rarely, a doctor may use a tiny tube that pierces the eardrum to drain fluid from the middle ear — a procedure called tympanocentesis. The fluid is tested for viruses and bacteria. This can be helpful if an infection hasn’t responded well to previous treatments.

- Other tests. If your child has had multiple ear infections or fluid buildup in the middle ear, your doctor may refer you to a hearing specialist (audiologist), speech therapist or developmental therapist for tests of hearing, speech skills, language comprehension or developmental abilities.

Previous diagnostic criteria for acute otitis media were based on symptomatology without otoscopic findings of inflammation. The updated American Academy of Pediatrics guideline endorses more stringent otoscopic criteria for diagnosis 6. An acute otitis media diagnosis requires moderate to severe bulging of the tympanic membrane (see Figure 3), new onset of ear discharge (otorrhea) not caused by otitis externa, or mild bulging of the tympanic membrane associated with recent onset of ear pain (less than 48 hours) or erythema. Acute otitis media should not be diagnosed in children who do not have objective evidence of middle ear effusion 6. An inaccurate diagnosis can lead to unnecessary treatment with antibiotics and contribute to the development of antibiotic resistance.

Otitis media with effusion (serous otitis media) is defined as middle ear effusion in the absence of acute symptoms 8. If otitis media with effusion is suspected and the presence of effusion on otoscopy is not evident by loss of landmarks, pneumatic otoscopy, tympanometry, or both should be used 9. Pneumatic otoscopy is a useful technique for the diagnosis of acute otitis media and otitis media with effusion 6 and is 70% to 90% sensitive and specific for determining the presence of middle ear effusion. By comparison, simple otoscopy is 60% to 70% accurate 8. Inflammation with bulging of the tympanic membrane on otoscopy is highly predictive of acute otitis media 5. Pneumatic otoscopy is most helpful when ear wax (cerumen) is removed from the external auditory canal.

Tympanometry and acoustic reflectometry are valuable adjuncts to otoscopy or pneumatic otoscopy 6. Tympanometry has a sensitivity and specificity of 70% to 90% for the detection of middle ear fluid, but is dependent on patient cooperation 10. Combined with normal otoscopy findings, a normal tympanometry result may be helpful to predict absence of middle ear effusion. Acoustic reflectometry has lower sensitivity and specificity in detecting middle ear effusion and must be correlated with the clinical examination 11. Tympanocentesis is the preferred method for detecting the presence of middle ear effusion and documenting bacterial cause 6, but is rarely performed in the primary care setting.

Acute otitis media treatment

Painkillers or pain relievers should be provided when necessary, including to pre-verbal children with behavioral manifestations of pain (eg, tugging or rubbing the ear, excessive crying or fussiness). Painkillers are recommended for symptoms of ear pain, fever, and irritability 6. Painkillers are particularly important at bedtime because disrupted sleep is one of the most common symptoms motivating parents to seek care 12. Oral analgesics, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen have been shown to be effective; weight-based doses are used for children 13. Ibuprofen is preferred, given its longer duration of action and its lower toxicity in the event of overdose 12. Topical analgesics, such as benzocaine, can also be helpful 14. A variety of topical agents are available by prescription and over the counter. Although not well studied, some topical agents may provide transient relief but probably not for more than 20 to 30 minutes. Topical agents should not be used when there is a tympanic membrane perforation.

Although 80% of cases resolve spontaneously, in the US, antibiotics are often given. Antibiotics relieve symptoms quicker (although results after 1 to 2 weeks are similar) and may reduce the chance of residual hearing loss and labyrinthine or intracranial complications. However, with the recent emergence of resistant organisms, pediatric organizations have strongly recommended initial antibiotics only for certain children (eg, those who are younger or more severely ill or for those with recurrent acute otitis media (eg, ≥ 4 episodes in 6 months). Antibiotics should be routinely prescribed for children with acute otitis media who are six months or older with severe signs or symptoms (i.e., moderate or severe otalgia, otalgia for at least 48 hours, or temperature of 102.2°F [39°C] or higher), and for children younger than two years with bilateral acute otitis media regardless of additional signs or symptoms 6.

Others, provided there is good follow-up, can safely be observed for 48 to 72 hours and given antibiotics only if no improvement is seen; if follow-up by phone is planned, a prescription can be given at the initial visit to save time and expense. Decision to observe should be discussed with the caregiver.

Among children with mild symptoms, observation may be an option in those six to 23 months of age with unilateral acute otitis media, or in those two years or older with bilateral or unilateral acute otitis media 6. A large prospective study of this strategy found that two out of three children will recover without antibiotics 15. Recently, the American Academy of Family Physicians recommended not prescribing antibiotics for otitis media in children two to 12 years of age with nonsevere symptoms if observation is a reasonable option 16. If observation is chosen, a mechanism must be in place to ensure appropriate treatment if symptoms persist for more than 48 to 72 hours. Strategies include a scheduled follow-up visit or providing patients with a backup antibiotic prescription to be filled only if symptoms persist 17.

In adults, topical intranasal vasoconstrictors, such as phenylephrine 0.25% 3 drops every 3 hours, improve eustachian tube function. To avoid rebound congestion, these preparations should not be used > 4 days. Systemic decongestants (eg, pseudoephedrine 30 to 60 mg orally every 6 hours as needed) may be helpful. Antihistamines (eg, chlorpheniramine 4 mg orally every 4 to 6 hours for 7 to 10 days) may improve eustachian tube function in people with allergies but should be reserved for the truly allergic.

For children, neither vasoconstrictors nor antihistamines are of benefit.

Myringotomy may be done for a bulging tympanic membrane, particularly if severe or persistent pain, fever, vomiting, or diarrhea is present. The patient’s hearing, tympanometry, and tympanic membrane appearance and movement are monitored until normal.

A wait-and-see approach

Symptoms of middle ear infections usually improve within the first couple of days, and most acute otitis media clear up on their own within one to two weeks without any treatment. The American Academy of Pediatrics and the American Academy of Family Physicians recommend a wait-and-see approach as one option for:

- Children 6 to 23 months with mild middle ear pain in one ear for less than 48 hours and a temperature less than 102.2 °F (39 °C)

- Children 24 months and older with mild middle ear pain in one or both ears for less than 48 hours and a temperature less than 102.2 °F (39 °C)

Some evidence suggests that treatment with antibiotics might be helpful for certain children with middle ear infections. On the other hand, using antibiotics too often can cause bacteria to become resistant to the medicine. Talk with your doctor about the potential benefits and risks of using antibiotics.

Your doctor will also advise you on treatments to lessen pain from an ear infection. These may include the following:

- Pain medication. Your doctor may advise the use of over-the-counter acetaminophen (Tylenol, others) or ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) to relieve pain. Use the drugs as directed on the label.

- Use caution when giving aspirin to children or teenagers. Children and teenagers recovering from chickenpox or flu-like symptoms should never take aspirin because aspirin has been linked with Reye’s syndrome. Talk to your doctor if you have concerns.

- Anesthetic drops. These may be used to relieve pain if the eardrum doesn’t have a hole or tear in it.

Acute otitis media antibiotics

A virus or bacteria can cause acute otitis media. Antibiotics will not help an infection that is caused by a virus. Most health care providers don’t prescribe antibiotics for every ear infection. However, all children younger than 6 months with acute otitis media are treated with antibiotics.

After an initial observation period, your doctor may recommend antibiotic treatment for an ear infection in the following situations:

- Children 6 months and older with moderate to severe ear pain in one or both ears for at least 48 hours or a temperature of 102.2 °F (39 °C) or higher

- Children 6 to 23 months with mild middle ear pain in one or both ears for less than 48 hours and a temperature less than 102.2 °F (39 °C)

- Children 24 months and older with mild middle ear pain in one or both ears for less than 48 hours and a temperature less than 102.2 °F (39 °C)

Children younger than 6 months of age with confirmed acute otitis media are more likely to be treated with antibiotics without the initial observational waiting time.

Even after symptoms have improved, be sure to use the antibiotic as directed. DO NOT stop the medicine when symptoms go away. Failing to take all the antibiotics can lead to recurring infection and resistance of bacteria to antibiotic medications. Talk with your doctor or pharmacist about what to do if you accidentally miss a dose.

If the antibiotics do not seem to be working within 48 to 72 hours, contact your doctor. You may need to switch to a different antibiotic.

Side effects of antibiotics may include nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. Although rare, serious allergic reactions may also occur.

Some children have repeat ear infections that seem to go away between episodes. They may receive a smaller, daily dose of antibiotics to prevent new infections.

Tables 1 and 2 summarize the antibiotic options for children with acute otitis media. High-dose amoxicillin should be the initial treatment in the absence of a known allergy 6 The advantages of amoxicillin include low cost, acceptable taste, safety, effectiveness, and a narrow microbiologic spectrum. Children who have taken amoxicillin in the past 30 days, who have conjunctivitis, or who need coverage for β-lactamase–positive organisms should be treated with high-dose amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin) 6.

Oral cephalosporins, such as cefuroxime (Ceftin), may be used in children who are allergic to penicillin. Recent research indicates that the degree of cross reactivity between penicillin and second- and third-generation cephalosporins is low (less than 10% to 15%), and avoidance is no longer recommended 18. Because of their broad-spectrum coverage, third-generation cephalosporins in particular may have an increased risk of selection of resistant bacteria in the community 19. High-dose azithromycin (Zithromax; 30 mg per kg, single dose) appears to be more effective than the commonly used five-day course, and has a similar cure rate as high-dose amoxicillin/clavulanate 6. However, excessive use of azithromycin is associated with increased resistance, and routine use is not recommended 6. Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is no longer effective for the treatment of acute otitis media due to evidence of Streptococcus pneumoniae resistance 20.

Intramuscular or intravenous ceftriaxone (Rocephin) should be reserved for episodes of treatment failure or when a serious comorbid bacterial infection is suspected 12. One dose of ceftriaxone may be used in children who cannot tolerate oral antibiotics because it has been shown to have similar effectiveness as high-dose amoxicillin 21. A three-day course of ceftriaxone is superior to a one-day course in the treatment of nonresponsive acute otitis media caused by penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae 21. Although some children will likely benefit from intramuscular ceftriaxone, overuse of this agent may significantly increase high-level penicillin resistance in the community 12. High-level penicillin-resistant pneumococci are also resistant to first- and third-generation cephalosporins.

Antibiotic therapy for acute otitis media is often associated with diarrhea 22. Probiotics and yogurts containing active cultures reduce the incidence of diarrhea and should be suggested for children receiving antibiotics for acute otitis media 22. There is no compelling evidence to support the use of complementary and alternative treatments in acute otitis media 6.

Table 1. Antibiotics for Otitis Media

| Drug | Dose* (by Age) | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Initial treatment | ||

| Amoxicillin | < 14 years: 40–45 mg/kg every 12 hours > 14 years: 500 mg every 8 hours | Preferred unless the child has one of the following:

High-dose regimen for possible resistant organisms |

| Penicillin-allergic† | ||

| Cefdinir | 14 mg/kg once a day or 7 mg/kg every 12 hours | — |

| Cefuroxime | < 14 years: 15 mg/kg every 12 hours > 14 years: 500 mg every 12 hours | Maximum 1000 mg/day |

| Cefpodoxime | 5 mg/kg every 12 hours | — |

| Ceftriaxone | 50 mg/kg IM or IV once May repeat at 72 hours | Consider particularly for children with severe vomiting or who will not swallow antibiotic liquids |

| Resistant cases‡ | ||

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate | < 14 years: 40–45 mg/kg every 12 hours ≥ 14 years: 500 mg every 12 hours | Preferred; dose based on amoxicillin component Use new formulation to limit clavulanate to maximum of 10 mg/kg/day |

| Ceftriaxone | 50 mg/kg IM or IV once a day for 3 days | Can use even if failed on oral cephalosporin Considered if adherence is likely to be poor |

| Clindamycin | 10 to 13 mg/kg every 8 hours | 2nd-line alternative, consider using along with a cephalosporin |

| *Treatment duration is typically 10 days for children < 2 years and 7 days for older children unless otherwise specified. Drugs are given orally unless otherwise specified. | ||

| †Cross reactivity of 2nd- and 3rd-generation cephalosporins with penicillin is very low. | ||

| ‡No improvement after 48 to 72 hours of treatment, or previous resistant infection; amoxicillin used in the previous 30 days; or concurrent purulent conjunctivitis | ||

Table 2. Recommended Antibiotics for (Initial or Delayed) Treatment and for Patients Who Have Failed Initial Antibiotic Therapy

| Initial immediate or delayed antibiotic treatment | Antibiotic treatment after 48–72 hours of failure of initial antibiotic treatment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recommended first-line treatment | Alternative treatment (if penicillin allergy) | Recommended first-line treatment | Alternative treatment | ||

|

|

|

| ||

Footnotes:

Cefdinir, cefuroxime, cefpodoxime, and ceftriaxone are highly unlikely to be associated with cross-reactivity with penicillin allergy on the basis of their distinct chemical structures.

*—May be considered in patients who have received amoxicillin in the previous 30 d or who have the otitis-conjunctivitis syndrome.

†—Perform tympanocentesis/drainage if skilled in the procedure, or seek a consultation from an otolaryngologist for tympanocentesis/drainage. If the tympanocentesis reveals multidrug-resistant bacteria, seek an infectious disease specialist consultation.

Abbreviations: IM = intramuscular; IV = intravenous.

[Source 6 ]Infants eight weeks or younger

Young infants are at increased risk of severe sequelae from suppurative acute otitis media. Middle ear pathogens found in neonates younger than two weeks include group B streptococcus, gram-negative enteric bacteria, and Chlamydia trachomatis 23. Febrile neonates younger than two weeks with apparent acute otitis media should have a full sepsis workup, which is indicated for any febrile neonate 23. Empiric amoxicillin is acceptable for infants older than two weeks with upper respiratory tract infection and acute otitis media who are otherwise healthy 24.

Persistent or recurrent acute otitis media

Children with persistent, significant acute otitis media symptoms despite at least 48 to 72 hours of antibiotic therapy should be reexamined 6. If a bulging, inflamed tympanic membrane is observed, therapy should be changed to a second-line agent 12. For children initially on amoxicillin, high-dose amoxicillin/clavulanate is recommended 6.

For children with an amoxicillin allergy who do not improve with an oral cephalosporin, intramuscular ceftriaxone, clindamycin, or tympanocentesis may be considered 4. If symptoms recur more than one month after the initial diagnosis of acute otitis media, a new and unrelated episode of acute otitis media should be assumed 8. For children with recurrent acute otitis media (i.e., three or more episodes in six months, or four episodes within 12 months with at least one episode during the preceding six months) with middle ear effusion, tympanostomy tubes may be considered to reduce the need for systemic antibiotics in favor of observation, or topical antibiotics for tube otorrhea 6. However, tympanostomy tubes may increase the risk of long-term tympanic membrane abnormalities and reduced hearing compared with medical therapy 25. Other strategies may help prevent recurrence 26.

Strategies for preventing recurrent otitis media

- Check for undiagnosed allergies leading to chronic rhinorrhea

- Eliminate bottle propping and pacifiers 27

- Eliminate exposure to passive smoke 28

- Routinely immunize with the pneumococcal conjugate and influenza vaccines 29

- Use xylitol gum in appropriate children (two pieces, five times a day after meals and chewed for at least five minutes) 26

Probiotics, particularly in infants, have been suggested to reduce the incidence of infections during the first year of life. Although available evidence has not demonstrated that probiotics prevent respiratory infections 30, probiotics do not cause adverse effects and need not be discouraged. Antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended 6.

Serous otitis media treatment

Management of otitis media with effusion is summarized below. Two rare complications of otitis media with effusion are transient hearing loss potentially associated with language delay, and chronic anatomic injury to the tympanic membrane requiring reconstructive surgery 9. Children should be screened for speech delay at all visits. If a developmental delay is apparent or middle ear structures appear abnormal, the child should be referred to an otolaryngologist 9. Antibiotics, decongestants, and nasal steroids do not hasten the clearance of middle ear fluid and are not recommended 31.

Diagnosis and treatment of otitis media with effusion 9:

- Evaluate tympanic membranes at every well-child and sick visit if feasible; perform pneumatic otoscopy or tympanometry when possible (consider removing cerumen)

- If transient effusion is likely, reevaluate at three-month intervals, including screening for language delay; if there is no anatomic damage or evidence of developmental or behavioral complications, continue to observe at three- to six-month intervals; if complications are suspected, refer to an otolaryngologist

- For effusion that appears to be associated with anatomic damage, such as adhesive otitis media or retraction pockets, reevaluate in four to six weeks; if abnormality persists, refer to an otolaryngologist

- Antibiotics, decongestants, and nasal steroids are not indicated

Surgery

If acute otitis media does not go away with the usual medical treatment, or if a child has many ear infections over a short period of time, your child’s doctor may recommend ear tubes or tympanostomy tubes:

- A tiny tube is inserted into the eardrum, keeping open a small hole that allows air to get in so fluids can drain more easily.

- Usually the tubes fall out by themselves. Those that don’t fall out may be removed in the provider’s office.

Tympanostomy tubes are appropriate for children six months to 12 years of age who have had bilateral otitis media with effusion for three months or longer with documented hearing difficulties, or for children with recurrent acute otitis media who have evidence of middle ear effusion at the time of assessment for tube candidacy. Tympanostomy tubes are not indicated in children with a single episode of otitis media with effusion of less than three months’ duration, or in children with recurrent acute otitis media who do not have middle ear effusion in either ear at the time of assessment for tube candidacy. Children with chronic otitis media with effusion who did not receive tubes should be reevaluated every three to six months until the effusion is no longer present, hearing loss is detected, or structural abnormalities of the tympanic membrane or middle ear are suspected 32.

Children with tympanostomy tubes who present with acute uncomplicated otorrhea should be treated with topical antibiotics and not oral antibiotics. Routine, prophylactic water precautions such as ear plugs, headbands, or avoidance of swimming are not necessary for children with tympanostomy tubes 32.

If the adenoids are enlarged, removing them with surgery may be considered if ear infections continue to occur. Removing tonsils does not seem to help prevent ear infections.

Treatment for chronic suppurative otitis media

Chronic infection that results in a hole or tear in the eardrum — called chronic suppurative otitis media — is difficult to treat. It’s often treated with antibiotics administered as drops. You may receive instructions on how to suction fluids out through the ear canal before administering drops.

Acute otitis media prognosis

Most often, acute otitis media is a minor problem that gets better 33. Acute otitis media can be treated, but they may occur again in the future. Death from acute otitis media is rare in the era of modern medicine. With effective antibiotic therapy, the systemic signs of fever and lethargy should begin to dissipate, along with the localized pain, within 48 hours. Children with fewer than 3 episodes of acute otitis media are 3 times more likely to resolve with a single course of antibiotics, as are children who develop acute otitis media in nonwinter months 34. Typically, patients eventually recover the conductive hearing loss associated with acute otitis media.

Most children will have slight short-term hearing loss during and right after an acute otitis media. This is due to fluid in the middle ear (middle ear effusion). Fluid can stay behind the eardrum for weeks or even months after the infection has cleared. Middle ear effusion and conductive hearing loss can be expected to persist well beyond the duration of therapy, with up to 70% of children expected to have middle ear effusion after 14 days, 50% at 1 month, 20% at 2 months, and 10% after 3 months, irrespective of therapy.

In most instances, persistent middle ear effusion can merely be observed without antimicrobial therapy; however, a second course of either the same antibiotic or a drug of a different mechanism of action may be warranted to prevent a relapse before resolution.

Speech or language delay is uncommon. It may occur in a child who has lasting hearing loss from many repeated acute otitis media.

Children with a history of prelingual otitis media are at risk for a mild-to-moderate conductive hearing loss. Children with otitis media in the first 24 months of life often have difficulty perceiving strident or high-frequency consonants, such as sibilants.

References- Schilder, A. G., Chonmaitree, T., Cripps, A. W., Rosenfeld, R. M., Casselbrant, M. L., Haggard, M. P., & Venekamp, R. P. (2016). Otitis media. Nature reviews. Disease primers, 2(1), 16063. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.63

- Ubukata K, Morozumi M, Sakuma M, Takata M, Mokuno E, Tajima T, Iwata S; AOM Surveillance Study Group. Etiology of Acute Otitis Media and Characterization of Pneumococcal Isolates After Introduction of 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine in Japanese Children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2018 Jun;37(6):598-604. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001956

- Otitis Media: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2013 Oct 1;88(7):435-440. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2013/1001/p435.html

- Arrieta A, Singh J. Management of recurrent and persistent acute otitis media: new options with familiar antibiotics. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23(2 suppl):S115–S124.

- Coker TR, Chan LS, Newberry SJ, et al. Diagnosis, microbial epidemiology, and antibiotic treatment of acute otitis media in children: a systematic review. JAMA. 2010;304(19):2161–2169.

- Lieberthal AS, Carroll AE, Chonmaitree T, et al. The diagnosis and management of acute otitis media. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):e964–e999.

- Danishyar A, Ashurst JV. Acute Otitis Media. [Updated 2021 Mar 16]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470332

- Shekelle PG, Takata G, Newberry SJ, et al. Management of acute otitis media: update. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2010;(198):1–426.

- American Academy of Family Physicians; American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery; American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Otitis Media with Effusion. Otitis media with effusion. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):1412–1429.

- Watters GW, Jones JE, Freeland AP. The predictive value of tympanometry in the diagnosis of middle ear effusion. Clin Otolayngol Allied Sci. 1997;22(4):343–345.

- Kimball S. Acoustic reflectometry: spectral gradient analysis for improved detection of middle ear effusion in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1998;17(6):552–555.

- Burrows HL, Blackwood RA, Cooke JM, et al.; Otitis Media Guideline Team. University of Michigan Health System otitis media guideline. http://www.med.umich.edu/1info/FHP/practiceguides/om/OM.pdf

- Bertin L, Pons G, d’Athis P, et al. A randomized, double-blind, multi-centre controlled trial of ibuprofen versus acetaminophen and placebo for symptoms of acute otitis media in children. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1996;10(4):387–392.

- Hoberman A, Paradise JL, Reynolds EA, et al. Efficacy of Auralgan for treating ear pain in children with acute otitis media. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151(7):675–678.

- Marchetti F, Ronfani L, Nibali SC, et al.; Italian Study Group on Acute Otitis Media. Delayed prescription may reduce the use of antibiotics for acute otitis media: a prospective observational study in primary care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(7):679–684.

- Antibiotics for Otitis Media. https://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/cw-otitis-media.html

- Siegel RM, Kiely M, Bien JP, et al. Treatment of otitis media with observation and a safety-net antibiotic prescription. Pediatrics. 2003;112(3 pt 1):527–531.

- Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters; American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; Joint Council of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Drug allergy: an updated practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105(4):259–273.

- Arguedas A, Dagan R, Leibovitz E, et al. A multicenter, open label, double tympanocentesis study of high dose cefdinir in children with acute otitis media at high risk of persistent or recurrent infection. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25(3):211–218.

- Doern GV, Pfaller MA, Kugler K, et al. Prevalence of antimicrobial resistance among respiratory tract isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae in North America: 1997 results from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27(4):764–770.

- Leibovitz E, Piglansky L, Raiz S, et al. Bacteriologic and clinical efficacy of one day vs. three day intramuscular ceftriaxone for treatment of nonresponsive acute otitis media in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19(11):1040–1045.

- Johnston BC, Goldenberg JZ, Vandvik PO, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of pediatric antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011(11):CD004827

- Nozicka CA, Hanly JG, Beste DJ, et al. Otitis media in infants aged 0–8 weeks: frequency of associated serious bacterial disease. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1999;15(4):252–254.

- Turner D, Leibovitz E, Aran A, et al. Acute otitis media in infants younger than two months of age: microbiology, clinical presentation and therapeutic approach. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2002;21(7):669–674.

- Stenstrom R, Pless IB, Bernard P. Hearing thresholds and tympanic membrane sequelae in children managed medically or surgically for otitis media with effusion [published correction appears in Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(6):588]. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(12):1151–1156.

- Azarpazhooh A, Limeback H, Lawrence HP, et al. Xylitol for preventing acute otitis media in children up to 12 years of age. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011(11):CD007095

- Niemelä M, Pihakari O, Pokka T, et al. Pacifier as a risk factor for acute otitis media: a randomized, controlled trial of parental counseling. Pediatrics. 2000;106(3):483–488.

- Etzel RA, Pattishall EN, Haley NJ, et al. Passive smoking and middle ear effusion among children in day care. Pediatrics. 1992;90(2 pt 1):228–232.

- Fireman B, Black SB, Shinefield HR, et al. Impact of the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine on otitis media [published correction appears in Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(2):163]. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22(1):10–16.

- Weichert S, Schroten H, Adam R. The role of prebiotics and probiotics in prevention and treatment of childhood infectious diseases. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(8):859–862.

- Gluth MB, McDonald DR, Weaver AL, et al. Management of eustachian tube dysfunction with nasal steroid spray: a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137(5):449–455.

- Rosenfeld RM, Schwartz SR, Pynnonen MA, et al. Clinical practice guideline: tympanostomy tubes in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;149(1 suppl):S1–S35.

- Paradise, J. L., Hoberman, A., Rockette, H. E., & Shaikh, N. (2013). Treating acute otitis media in young children: what constitutes success?. The Pediatric infectious disease journal, 32(7), 745–747. https://doi.org/10.1097/INF.0b013e31828e1417

- Tähtinen PA, Laine MK, Ruohola A. Prognostic Factors for Treatment Failure in Acute Otitis Media. Pediatrics. 2017 Sep;140(3):e20170072. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0072