Alcohol withdrawal syndrome

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome is a collection of withdrawal symptoms that may occur when a person who has been drinking too much alcohol on a regular basis suddenly stops or greatly reduced drinking alcohol 1. Approximately 50% of individuals with alcohol use disorder who abruptly stop or reduce their alcohol use will develop signs or symptoms of alcohol withdrawal syndrome 2. Alcohol use disorder is diagnosed in individuals who drink excessively and whose functioning (social, psychological, physical) is at least moderately impacted by their drinking. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome can occur within 6–24 hours to four or five days after the abrupt discontinuation or decrease of alcohol consumption. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome signs and symptoms include sweating, rapid heartbeat, hand tremors, problems sleeping (insomnia), nausea and vomiting, hallucinations, restlessness and agitation, anxiety, and occasionally seizures 3. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome is a potentially life-threatening condition whose severity ranges from mild/moderate forms characterized by tremors, nausea, anxiety, and depression, to severe forms characterized by hallucinations, seizures, delirium tremens and coma 4. If untreated or inadequately treated, alcohol withdrawal can progress to generalized tonic-clonic seizures, delirium tremens, and death 5.

Your alcohol withdrawal symptoms will be at their worst for the first 48 hours. Alcohol withdrawal symptoms can be severe enough to impair your ability to function at work or in social situations. You’ll also find your sleep is disturbed. You may wake up several times during the night or have problems getting to sleep. This is to be expected, and your sleep patterns should return to normal within a month. Your alcohol withdrawal symptoms should gradually start to improve as your body begins to adjust to being without alcohol. This usually takes 3 to 7 days from the time of your last drink. Alcohol withdrawal symptoms are relieved immediately by consuming additional alcohol 6. However, if you’re dependent on alcohol to function, it’s recommended you seek medical advice to manage your alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Furthermore, you’ll need further treatment and support to help you in the long term. People who have gone through alcohol withdrawal syndrome before are more likely to have symptoms each time they quit drinking. You may also have more severe alcohol withdrawal symptoms if you have certain other medical problems.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome represents a continuous spectrum of symptoms ranging from mild withdrawal symptoms to delirium tremens (DT). Signs and symptoms of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, divided by stage 7, 1:

- Stage 1 – Minor alcohol withdrawal symptoms: Symptoms include anxiety, nausea, and vomiting. It occurs around 8 hours after the last drink of alcohol.

- Stage 2 – Alcoholic hallucinosis: Here there may be hallucinations (visual [zoopsy], auditory [voices] and tactile [paresthesia]) and hypertension 8. Symptoms occur within 12 to 24 hours after the last drink.

- Stage 3 – Alcohol withdrawal with seizures: Generalized tonic-clonic seizures (with short or no postictal period). It usually occurs 24 to 48 hours after the last drink.

- Stage 4 – Delirium tremens: Delirium tremens is an acute episode of sudden confusion (delirium) caused by alcohol withdrawal and is the most severe form of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, potentially leading to intensive care unit (ICU) admission or death 9. Delirium tremens can cause confusion (delirium), panic, hallucinations (seeing, hearing, or feeling things that aren’t real), psychosis, hyperthermia, malignant hypertension, seizures and coma. Some studies estimate that 3% to 5% of hospitalized patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome progress to delirium tremens 10. Delirium tremens usually occurs 48 to 72 hours after the last drink. Delirium tremens may lead to death in about 5%–10% of the cases, if not managed properly 11.

Common alcohol withdrawal symptoms include:

- Anxiety or nervousness

- Depression

- Fatigue

- Irritability

- Jumpiness or shakiness

- Mood swings

- Nightmares

- Not thinking clearly

Other alcohol withdrawal symptoms may include:

- Sweating, clammy skin

- Enlarged (dilated) pupils

- Headache

- Insomnia (sleeping difficulty)

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea and vomiting

- Pallor

- Rapid heart rate

- Sweating, clammy skin

- Tremor of the hands or other body parts

A severe form of alcohol withdrawal called delirium tremens can cause:

- Agitation

- Fever

- Seeing or feeling things that aren’t there (hallucinations)

- Seizures

- Severe confusion

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome occurs most often in adults. Chronic alcoholism and withdrawal are more common in men than in women 12. But, alcohol withdrawal syndrome may also occur in teenagers or children. The more you drink regularly, the more likely you are to develop alcohol withdrawal syndrome when you stop drinking.

The withdrawal response after discontinuation of a particular drug or alcohol can depend on the duration and quantity of use 13. When people consume alcohol for at least 1 to 3 months or even consume large quantities for at least seven to ten days, the withdrawal response can occur within 6 to 24 hours after cessation of alcohol 14.

About 20% of adults in the emergency room may suffer from alcohol use disorder 12 and about 4-40% of patients admitted to ICU will have alcohol withdrawal syndrome 15. Patients who have alcohol withdrawal syndrome have an increased length of hospital stay and increased mortality than those who do not have alcohol withdrawal syndrome 16.

Talk to your doctor if you think you are going through alcohol withdrawal. It does not matter if your symptoms are mild or severe. The doctor needs to know your problem and if you have had it before. They will treat and manage your alcohol withdrawal symptoms to make sure they don’t lead to other health problems. If you go through alcohol withdrawal more than once and don’t receive treatment, your symptoms can get worse each time.

Treatment for alcohol withdrawal using benzodiazepines and any other medicinal combinations should always be under the supervision of a board-certified physician or psychiatrist. You should never try to withdraw from alcohol using benzodiazepines on your own.

Your doctor will help you manage your alcohol withdrawal symptoms to prevent more serious health problems. Your doctor may prescribe medicine to treat your symptoms. Medicines can help control shakiness, anxiety, and confusion. It can help to take these medicines early on in your withdrawal period. They can keep symptoms from getting worse or lasting as long.

Some people may be prescribed medication to help achieve alcohol abstinence. It’s likely the medication will make you feel drowsy. Only take your medication as directed. Benzodiazepines administration represents the “gold-standard” for the management of any grade of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, including seizures and delirium tremens. In particular, the European Federation of Neurological Societies recommends the use of benzodiazepines for the primary prevention and for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome-related seizures. The drugs of choice are lorazepam and diazepam. Although lorazepam has some pharmacological advantages to diazepam, the differences are minor and, because i.v. lorazepam is largely unavailable in Europe, diazepam is recommended. Other drugs for detoxification should only be considered as add-on treatments 17. Despite its primary indication as anticonvulsivant drug, phenytoin has been shown to be ineffective in the secondary prevention of alcohol withdrawal seizures in placebo-controlled trials 18. Thus its use should be avoided.

Other medicines used with benzodiazepines or in place of them include 19:

- Acamprosate – Acamprosate is an FDA-approved medication for alcoholism that reduces cravings. Acamprosate can be used with counseling to help readjust the brain to prevent you from drinking.

- Anticonvulsants – Certain anticonvulsants help regulate brain activity during medical detox.

- Opioid antagonists – Opioid antagonists are used to help those detoxing from opioid misuse.

- Barbiturates – Barbiturates work similarly to benzodiazepines and may be used when benzodiazepines are contraindicated.

- Beta-blockers – Beta-blockers are sometimes used for acute anxiety or sleep issues and may be used in place of benzodiazepines.

- GABA agonists – GABA agonists are typically prescribed to assist with sleep issues and seizures.

- Antipsychotics – In low doses, some antipsychotics may be useful in medical detox.

- Naltrexone (two brand names: Revia or Vivitrol) reduces cravings and blocks the alcohol “high.”

- Disulfiram (brand name: Antabuse) creates an unpleasant effect even when you consume only a small amount of alcohol.

- Nutritional therapy may also be part of medical detox and addiction treatment. For example, lack of thiamine, or vitamin B1, leads to cognitive impairments. Because many people with alcohol use disorder are vitamin B1 deficient, replacing it is crucial 20

People who have severe withdrawal often need to go to the hospital. They may need fluids to prevent or treat dehydration. They may need medicines to treat the alcohol withdrawal syndrome symptoms. These often are given through an IV. Your doctor can tell you what level of testing or treatment you need. After the treatment of acute alcohol withdrawal syndrome, some symptoms can persist from weeks to months following the 5–7 days of acute detoxification period, representing the “protracted alcohol withdrawal syndrome” 4.

You must not drive if you’re taking medication to help ease your alcohol withdrawal symptoms. You should also get advice about operating heavy machinery at work. You need to tell the DMV if you have an alcohol problem – failure to do so could result in a fine.

Detox can be a stressful time. Ways you can try to relieve stress include reading, listening to music, going for a walk, and taking a bath. During detox, make sure you drink plenty of fluids (about 3 liters a day). However, avoid drinking large amounts of caffeinated drinks, including tea and coffee, because they can make your sleep problems worse and cause feelings of anxiety. Water, squash or fruit juice are better choices.

Try to eat regular meals, even if you’re not feeling hungry. Your appetite will return gradually.

Your urge to drink again during alcohol withdrawal can be very strong. Support from family and friends can help you resist that urge. It’s important to avoid any triggers or situations that may make you want alcohol. This could mean avoiding certain places or people. You may also choose to attend self-help groups, receive extended counseling or use a talking therapy such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). After withdrawal symptoms go away, you may need more treatment. You can join a support group or sobriety program, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (https://www.aa.org).

If you’re detoxing at home, you’ll regularly see a nurse or another healthcare professional. This might be at home, your family physician or an alcohol withdrawal specialist service. You’ll also be given the relevant contact details for other support group or sobriety program such as National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (https://www.niaaa.nih.gov) or Al-Anon Family Groups/Al-Anon/Alateen (https://al-anon.org) should you need additional support. These programs can help prevent relapse.

What is delirium tremens syndrome?

Delirium tremens represents the most severe complication of alcohol withdrawal syndrome and it significantly increases the morbidity and mortality of patients 9. Risk factors for delirium tremens include sustained heavy drinking especially if you do not eat enough food, people who have used alcohol for more than 10 years, age older than 30 years, increased days since last alcohol intake, and a prior episode of delirium tremens 21. Delirium tremens is especially common in those who drink 4 to 5 pints (1.8 to 2.4 liters) of wine, 7 to 8 pints (3.3 to 3.8 liters) of beer, or 1 pint (1/2 liter) of “hard” alcohol every day for several months. Delirium tremens may also be caused by head injury, infection, or illness in people with a history of heavy alcohol use. Alcohol withdrawal delirium tremens is characterized by features of alcohol withdrawal itself (tremor, sweating, high blood pressure, fast heart beat etc.) together with general delirious symptoms such as clouded consciousness, confusion, hallucinations (seeing, hearing, or feeling things that aren’t real), panic, disorientation, disturbed circadian rhythms, thought processes and sensory disturbances, all of them fluctuating in time. Some studies estimate that 3% to 5% of hospitalized patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome progress to delirium tremens 10. Delirium tremens usually occurs 48 hours after the last drink. Delirium tremens may lead to death in about 5%–10% of the cases, if not managed properly 22, 23. Patients with delirium tremens should be treated in an inpatient setting. Delirium tremens treatment combines a supportive and symptomatic approach. Benzodiazepines in supramaximal doses are usually used as drugs of choice but in some European countries, clomethiazole is frequently used as well 9.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome symptoms

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome symptoms usually occur within 8 hours after your last drink, but can occur days later. In its mild-to-moderate forms, alcohol withdrawal syndrome symptoms such as increase in blood pressure and pulse rate, tremors, overactive reflexes, irritability, and anxiety usually develop within 6 to 24 hours after your last drink and may subside within few days 24. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome symptoms usually peak by 24 to 72 hours, but may go on for weeks. You’ll also find your sleep is disturbed. You may wake up several times during the night or have problems getting to sleep. This is to be expected, and your sleep patterns should return to normal within a month.

The types of symptoms experienced in alcohol withdrawal syndrome are broken down into three components: autonomic, motor, and psychiatric.

Autonomic symptoms are responses of the nervous system and include 25:

- Rapid heart rate

- Rapid breathing

- Dilated or larger than normal pupils

- Elevated blood pressure

- Elevated body temperature

- Diarrhea

- Nausea/vomiting

Motor symptoms are responses of the body’s nervous and muscular systems and include:

- Hand and body tremors

- Ataxia (impaired speech, balance, or coordination when not intoxicated)

- Changes in a person’s gait

- Hyper responsive reflexes

- Seizures

Psychological symptoms are changes to a person’s mood and perceptual experiences. These symptoms include:

- Paranoia

- Delusions (a fixed, false belief)

- Hallucinations (seeing, hearing, or feeling things that aren’t there)

- Mood instability

- Combativeness

- Agitation

- Disorientation

- Delirium

- Insomnia

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome represents a continuous spectrum of symptoms ranging from mild withdrawal symptoms to delirium tremens (DT). Alcohol withdrawal syndrome can start with mild symptoms and then evolve to more severe forms, or can start with delirium tremens, in particular in those patients with previous history of delirium tremens or with history of repeated alcohol withdrawal syndrome (kindling phenomenon) 2. Usually, 1st degree alcohol withdrawal syndrome symptoms (tremors, diaphoresis, nausea/vomiting, hypertension, tachycardia, hyperthermia, tachypnea) begin 6–12 hours after the last alcohol consumption, lasting until the next drink 26. In co-morbid patients taking other medications such as beta-blockers, significant changes in vital signs (blood pressure and heart rate) can be masked and appear normal. The 2nd degree alcohol withdrawal syndrome symptoms are characterized by visual and tactile disturbances and generally start 24 hours after the last drink. Almost 25% of alcohol withdrawal syndrome patients show transient alterations of perception such as auditory (voices) 27 or less frequently, visual (zooscopies) or tactile disturbances 26. They may be persecutory and cause paranoia, leading to increased patient agitation 28. When these symptoms become persistent, the patient has progressed to alcoholic hallucinosis. However, the patient recognizes the hallucinations as unreal, as dysperceptions, and maintains a clear sensorium 26.

Almost 10% of patients showing withdrawal symptoms develops alcohol withdrawal seizures (3rd degree alcohol withdrawal syndrome), generally starting after 24–48 hours from the last drink and characterized by diffuse, tonic-clonic seizures usually with little or no postictal period 29. Even if self-limiting in the majority of cases, seizures can be difficult to treat and almost in one-third of patients, delirium tremens may represent a clinical worsening of alcohol withdrawal seizures 30.

Delirium tremens represents the most severe manifestation (4th degree) of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, as the result of no treatment or undertreatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome and occurrs approximately in 5% of patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome 4. Usually it appears 48–72 hours after the last drink, although it could begin up to 10 days later. Symptoms last normally 5–7 days 31. Delirium tremens is characterized by a rapid fluctuation of consciousness and change in cognition occurring over a short period of time, accompanied by severe autonomic symptoms (sweating, nausea, palpitations and tremor) and psychological symptoms (i.e. anxiety). The typical delirium tremens patient shows agitation, hallucinations and disorientation. The presence of disorientation differentiates delirium from alcoholic hallucinosis 32. Delirium, psychosis, hallucinations, hyperthermia, malignant hypertension, seizures and coma are common manifestations of delirium tremens. Delirium tremens could be responsible of injury to patient or to staff, or of medical complications (aspiration pneumonia, arrhythmia or myocardial infarction), which may lead to death in 1–5% of patients 33.

After the treatment of acute alcohol withdrawal syndrome, some symptoms can persist from weeks to months following the 5–7 days of acute detoxification period, representing the “protracted alcohol withdrawal syndrome” 4.

Risk factors for severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome

Risk factors for severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome include 34, 7:

- Previous episodes of alcohol withdrawal (detoxification, rehabilitation, seizures, delirium tremens

- Concomitant use of CNS-depressant agents, such as benzodiazepine or barbiturates

- Concomitant use of other illicit substances

- High blood alcohol level (BAL) on admission (i.e. >200 mg/dl)

- Evidence of increased autonomic activity (i.e. systolic blood pressure > 150 mmHg, body temperature > 38°C)

- Older age

- Moderate to severe alcohol withdrawal at diagnosis (Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol – revised > 10)

- Medical or surgical illness (i.e. trauma, infection, liver disease, central nervous system (CNS) infection, electrolyte disturbances, hypoglycemia, etc.)

- Severe alcohol dependence

- Abnormal liver function (elevated aspartate aminotransferase [AST])

- Recent alcohol intoxication

- Male sex

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome pathophysiology

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome pathophysiology is complex. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome is due to overactivity of the central and autonomic nervous systems, leading to tremors, insomnia, nausea and vomiting, hallucinations, anxiety, and agitation. Most effects can be explained by the interaction of alcohol with neurotransmitters and neuroreceptors including gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glutamate (NMDA) 35. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) represents the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in central nervous system (brain and spinal cord) while glutamate represents the main excitatory neurotransmitter 2. The changes in the inhibitory and excitation neurotransmitters disrupting the neurochemical balance in the brain, causing symptoms of alcohol withdrawal.

Acute alcohol ingestion produces central nervous system (CNS) depression secondary to an enhanced GABAergic neurotransmission 36 and to a reduced glutamatergic activity. The stimulation of GABAA receptors 37 and the inhibition of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors represents the most known mechanisms 35.

Chronic central nervous system (CNS) exposure to alcohol produces adaptive changes in several neurotransmitter systems, including GABA, glutamate and norepinephrine pathways 38 in order to compensate for alcohol-induced destabilization and restore a neurochemical equilibrium 39. This adaptive phenomenon results in long-term reductions in the effects of alcohol in the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord), i.e., tolerance 30. In particular, changes observed after chronic alcohol exposure include a reduction in number, function, and sensitivity to GABA of the GABAA receptors (down-regulation) 40 and an increase in number, sensitivity and affinity for glutamate of NMDA receptors (up-regulation) 41. Ethanol inhibits opioid binding to P-opioid receptors, and long-term use results in the upregulation of opioid receptors 42. Opioid receptors in the nucleus accumbens and the ventral tegmental area of the brain modulate ethanol-induced dopamine release, this, in turn, produces alcohol craving and use of opioid antagonists to prevent this craving 43. More recently, an up-regulation of glutamate receptors alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA) and kainate has been described during alcohol withdrawal syndrome 44.

The abrupt reduction or cessation of alcohol intake produces an acute unbalance due both to the acute reduction of GABA activity and the increase of glutamatergic action, with consequent hyper excitability and development of alcohol withdrawal syndrome symptoms which may start as early as a few hours after the last alcohol intake 39. The up-regulation of dopaminergic and noradrenergic pathways could be responsible for the development, respectively, of hallucinations and of autonomic hyperactivity during alcohol withdrawal syndrome 4.

“Kindling” is represented by an increased neuronal excitability and sensitivity after repeated episodes of alcohol withdrawal syndrome 45. “Kindling” has been proposed to explain the risk of progression of some patients from milder to more severe forms of alcohol withdrawal syndrome.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome complications

Complications that can accompany alcohol withdrawal syndrome include 46:

- Delirium tremens

- Seizures

- Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Sleep disturbances

- Hallucinations

- Cardiovascular complications

A variety of clinical conditions could be associated with alcohol withdrawal syndrome both as complication of the disease or of the treatment 4. In particular, infectious (i.e. pneumonia and sepsis) and neurological (Wernicke’s encephalopathy) complications could be associated with immune and nutritional deficits related to alcohol use disorder or can be the direct consequence of the mechanical ventilation and/or ICU stay due to respiratory depression 47. On this connection physicians should be aware of these risks in order to start an adequate treatment.

Moreover, it should be underlined that severe medical illnesses (i.e. pneumonia, coronary heart disease, alcohol liver disease and anaemia) have been reported to precipitate alcohol withdrawal syndrome and to increase the risk of severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome 33. In these patients a prophylactic treatment could be useful, regardless of the clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol (CIWA) score.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome prevention

Reduce or avoid alcohol. If you have a drinking problem, you should stop alcohol completely. Total and lifelong avoidance of alcohol (abstinence) is the safest approach.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome diagnosis

When alcohol is consumed in large quantities for a prolonged period (greater than two weeks) and then abruptly discontinued, withdrawal symptoms are likely to occur. Symptoms of alcohol withdrawal syndrome begin six to 24 hours after the last alcohol intake. Alcohol withdrawal affects the central nervous system, autonomic nervous system, and cognitive function 48. Patients have acute alcohol withdrawal syndrome if two of the following symptoms are present after the reduction or discontinuation of alcohol use 49: autonomic hyperactivity (sweating, tachycardia); increased hand tremor; insomnia; nausea or vomiting; transient visual, tactile, auditory hallucinations or illusions; psychomotor agitation; anxiety; or tonic-clonic seizures. If acute alcohol withdrawal syndrome is not treated or is undertreated, delirium tremens can occur. This condition is a severe hyperadrenergic state (i.e., hyperthermia, diaphoresis, tachypnea, tachycardia) characterized by disorientation, impaired attention and consciousness, and visual and/or auditory hallucinations 48.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome diagnosis depends on the severity of the patient’s condition 50. The severity of acute alcohol withdrawal syndrome can be classified into three stages 51.

- Stage 1 symptoms are mild and not usually associated with abnormal vital signs.

- Stage 2 symptoms are more intense and associated with abnormal vital signs (e.g., elevated blood pressure, respiration, and body temperature).

- Stage 3 includes delirium tremens or seizures. Progression to stage 2 or 3 can occur quickly without treatment.

Your health care provider will perform a physical exam. This may reveal:

- Abnormal eye movements

- Abnormal heart rhythms

- Dehydration (not enough fluids in the body)

- Fever

- Rapid breathing

- Rapid heart rate

- Shaky hands

Blood and urine tests, including a toxicology screen, may be done. Tests to be considered include:

- Glucose – liver disease due to alcoholism may reduce glycogen stores, and ethanol impairs gluconeogenesis. As a consequence, patients in alcohol withdrawal develop anxiety, agitation, tremor, seizures, and diaphoresis, all of which can occur with hypoglycemia.

- Arterial blood gas (ABG) – mixed acid-base disorders are common and often result from alcoholic ketoacidosis, volume-contraction alkalosis, and respiratory alkalosis.

- Complete blood count (CBC) – long-term alcohol ingestion causes myelosuppression (bone marrow suppression resulting in reduced production of red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets), thrombocytopenia (low blood platelet count) and anemia (lack of red blood cells). Megaloblastic anemia occurs with dietary deficiency of vitamin B-12 and folate; increased mean corpuscular volume (MCV) suggests this condition

- Metabolic panel – look for acidosis, dehydration, concurrent renal disease, and other abnormalities that can occur in chronic alcoholism. Calculate anion and delta gaps, which are helpful in differentiating mixed acid-base disorders. A low blood urea nitrogen (BUN) value is expected in alcoholic liver disease. Expect an elevated lipase level if pancreatitis is suspected. Obtain the blood ammonia level if hepatic encephalopathy is suspected.

- Magnesium, calcium, and liver function tests (LFTs) – may be indicated because patients with chronic alcoholism usually have a dietary magnesium deficiency and concurrent alcoholic hepatitis. Alcoholic pancreatitis may cause hypocalcemia.

- Urinalysis – check for ketones, as patients may have associated alcoholic ketoacidosis. Ketonuria without glycosuria to exclude alcoholic ketoacidosis and the ingestion of isopropyl alcohol. Myoglobinuria from rhabdomyolysis may be suspected when hematuria is noted on urinalysis.

- Cardiac markers – elevated creatine kinase (CK) and cardiac troponin levels may indicate myocardial infarction. Elevated CK level may be from rhabdomyolysis, which may be associated with adrenergic hyperactivity from alcohol withdrawal or myonecrosis if immobile.

- Prothrombin time (PT) – useful index of liver function; patients with cirrhosis are at risk for coagulopathy.

- Toxicology screening – consider measuring serum osmolality and screening for toxic alcohols if severely acidaemic. Other recreational drugs may be present as well.

- Imaging studies – chest radiography to evaluate for aspiration pneumonia, cardiomyopathy, and chronic heart failure.

- Head computed tomography (CT) – risk for intracranial bleeding because of cortical atrophy and coagulopathy.

- Electrocardiography (ECG) – a prolonged QTc interval has been described in patients with an alcohol withdrawal syndrome.

- Lumbar puncture – to rule out meningitis or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- Blood cultures may also be indicated if sepsis or endocarditis is suspected.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome DSM-5 diagnostic criteria

According to the American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of mental disorders (DSM-5) criteria, the diagnosis of alcohol withdrawal syndrome is based on the observation of signs and symptoms of withdrawal in those patients who experienced an abrupt reduction or cessation of alcohol consumption 32. DSM-5 requires the observation of at least two of the following symptoms: autonomic hyperactivity (sweating or tachycardia); increased hand tremor; insomnia; nausea or vomiting; transient visual, tactile or auditory hallucinations or illusions; psychomotor agitation; anxiety; and tonic–clonic seizures 32.

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Alcohol Withdrawal Syndrome 32:

- A. Cessation of (or reduction in) alcohol use that has been heavy and prolonged.

- B. Two (or more) of the following, developing within several hours to a few days after criterion A:

- Autonomic hyperactivity (e.g., sweating or pulse rate greater than 100 beats per minute)

- Increased hand tremor

- Insomnia

- Nausea or vomiting

- Transient visual, tactile, or auditory hallucination s or illusions

- Psychomotor agitation

- Anxiety

- Generalized tonic-clonic seizures

- C. The symptoms in criterion B cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

- D. The symptoms are not due to a general medical condition and are not better accounted for by another mental disorder.

- Specify if: With perceptual disturbances: This specifier applies in the rare instance when hallucinations (usually visual or tactile) occur with intact reality testing, or auditory, visual, or tactile illusions occur in the absence of a delirium.

- When hallucinations occur in the absence of delirium (i.e., in a clear sensorium), a diagnosis of substance/medication-induced psychotic disorder should be considered.

Diagnostic features

The essential feature of alcohol withdrawal is the presence of a characteristic withdrawal syndrome that develops within several hours to a few days after the cessation of (or reduction in) heavy and prolonged alcohol use (Criteria A and B). The withdrawal syndrome includes two or more of the symptoms reflecting autonomic hyperactivity and anxiety listed in Criterion B, along with gastrointestinal symptoms.

Withdrawal symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning (Criterion C). The symptoms must not be attributable to another medical condition and are not better explained by another mental disorder (e.g., generalized anxiety disorder), including intoxication or withdrawal from another substance (e.g., sedative, hypnotic, or anxiolytic withdrawal) (Criterion D).

Symptoms can be relieved by administering alcohol or benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam). The withdrawal symptoms typically begin when blood concentrations of alcohol decline sharply (i.e., within 4-12 hours) after alcohol use has been stopped or reduced. Reflecting the relatively fast metabolism of alcohol, symptoms of alcohol withdrawal usually peak in intensity during the second day of abstinence and are likely to improve markedly by the fourth or fifth day. Following acute withdrawal, however, symptoms of anxiety, insomnia, and autonomic dysfunction may persist for up to 3-6 months at lower levels of intensity.

Fewer than 10% of individuals who develop alcohol withdrawal will ever develop dramatic symptoms (e.g., severe autonomic hyperactivity, tremors, alcohol withdrawal delirium). Tonic-clonic seizures occur in fewer than 3% of individuals.

Associated features supporting diagnosis

Although confusion and changes in consciousness are not core criteria for alcohol withdrawal, alcohol withdrawal delirium may occur in the context of withdrawal. As is true for any agitated, confused state, regardless of the cause, in addition to a disturbance of consciousness and cognition, withdrawal delirium can include visual, tactile, or (rarely) auditory hallucinations (delirium tremens). When alcohol withdrawal delirium develops, it is likely that a clinically relevant medical condition may be present (e.g., liver failure, pneumonia, gastrointestinal bleeding, sequelae of head trauma, hypoglycemia, an electrolyte imbalance, postoperative status).

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome severity assessment

In clinical practice, physicians have the need to predict the probability of a patient to develop severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome. In particular, in those patients in whom a complete medical history is not available (i.e. emergency department, trauma unit, ICU), a high risk of complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome could orientate the medical decision toward a more aggressive treatment, despite presenting symptoms.

Validated instruments used to assess acute alcohol withdrawal syndrome severity include the Alcohol Withdrawal Scale (Table 1), the revised 10-item form of the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (Table 2), Luebeck Alcohol withdrawal Risk Scale (LARS) (Table 4) or the recently proposed PAWSS (Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale) (Table 5) 2. The self-completed, 10-item Short Alcohol Withdrawal Scale (SAWS) (Table 3) has been validated in the outpatient setting 52. Outpatient treatment is appropriate in patients with mild or moderate alcohol withdrawal syndrome, if there are no contraindications. Patients who have not had alcohol in at least five days may also receive outpatient treatment.

The Alcohol Withdrawal Scale (Table 1) and the revised 10-item form of the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA-Ar) scale have emerged as a useful tool to assess alcohol withdrawal syndrome severity, even in those patients presenting with severe withdrawal and delirium, without requiring the patient’s participation 53, 54.

The Alcohol Withdrawal Scale (Table 1) was developed in order to provide an assessment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, even in those patients presenting with severe withdrawal and delirium, without requiring the patient’s participation 55. In this connection, “hallucinations” and “contact” items were included for a better identification of delirium tremens 55. This scale consists of 2 subscales (S subscale: pulse rate, diastolic blood pressure, temperature, breathing rate, sweating, tremor; M subscale: agitation, contact, orientation, hallucination, anxiety) allowing a separate assessment of somatic and mental withdrawal symptoms. Mild alcohol withdrawal syndrome is identified by a total score ≤5; moderate alcohol withdrawal syndrome scores 6–9; severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome results in a score ≥10 (Table 1).

The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Revised (CIWA-Ar) scale requires limited patient cooperation to evaluate its ten symptoms (Table 2). The Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Revised (CIWA-Ar) Scores of less than 8 indicate mild withdrawal, scores of 8–15 indicate moderate withdrawal (marked autonomic arousal) and scores of greater than 15 points indicate severe withdrawal and are also predictive of the development of seizures and delirium 56. If Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Revised (CIWA-Ar) score is <8–10 pharmacological treatment is not necessary, while it may be appropriate in those patients scoring between 8 and 15, to prevent the progression to more severe forms of alcohol withdrawal syndrome (see table 3). Pharmacological treatment is strongly indicated in patients with Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Revised (CIWA-Ar) score >15. The evaluation of Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Revised (CIWA-Ar) score should be repeated at least every 8 hours. In patients with scores >8–10 or requiring treatment, Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Revised (CIWA-Ar) should be repeated every hour to evaluate the response to treatments. In using the CIWA-Ar, the clinical picture should be considered because medical and psychiatric conditions may mimic alcohol withdrawal symptoms. In addition, certain medications (e.g., beta blockers) may blunt the manifestation of these symptoms.

The initial LARS (Luebeck Alcohol withdrawal Risk Scale) scale (Table 3) applied to the patients consists of 22 items compiled in 4 subscores:

- LARS I: history of alcohol use (detoxification and withdrawal complications) and abuse of sedatives;

- LARS II. drinking habits and possible alcohol use complications during the past 4 weeks; in this subscale some items assumed to indicate bad physical condition prior to detoxification (malnutrition, sleep disturbances, etc.) were included;

- LARS III: clinical symptoms at clinical investigation;

- LARS IV: laboratory values of serum electrolytes at admission.

Table 1. Alcohol-Withdrawal Scale

| Alcohol-withdrawal Scale | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Score | ||||||

| Subscale S – somatic symptoms | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Pulse rate (per min) | <100 | 101–110 | 111–120 | >120 | ||

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | <95 | 96–100 | 101–105 | >105 | ||

| Temperature (°C) | <37.0 | 37.0–37.5 | 37.6–38.0 | >38.0 | ||

| Breathing (per min) | <20 | 20–24 | >24 | n.a. | ||

| Sweating | None | Mild (wet hands) | Moderate (forehead) | Severe (profuse) | ||

| Tremor | None | mild (arms raised + fingers spread | moderate (fingers spread) | severe (spontaneous) | ||

| Subscale M – mental symptoms | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Agitation | none | fastening | rolling in bed | try to leave bed | in rage | |

| Contact | short talk possible | easily distractable (i.e. noise) | drifting contact | dialogue impossible | ||

| Orientation (time, place. person, situation) | fully aware | one kind (i.e. time) | two kinds disturbed | totally confused | ||

| Hallucinations (visual, acoustic and tactile) | none | suggestive | one kind (i.e. visual) | two kinds (visual + tactile) | all kinds | visual hallucinations (as in a film) |

| Anxiety | None | mild (only if asked) | severe (spontaneous complaint) | |||

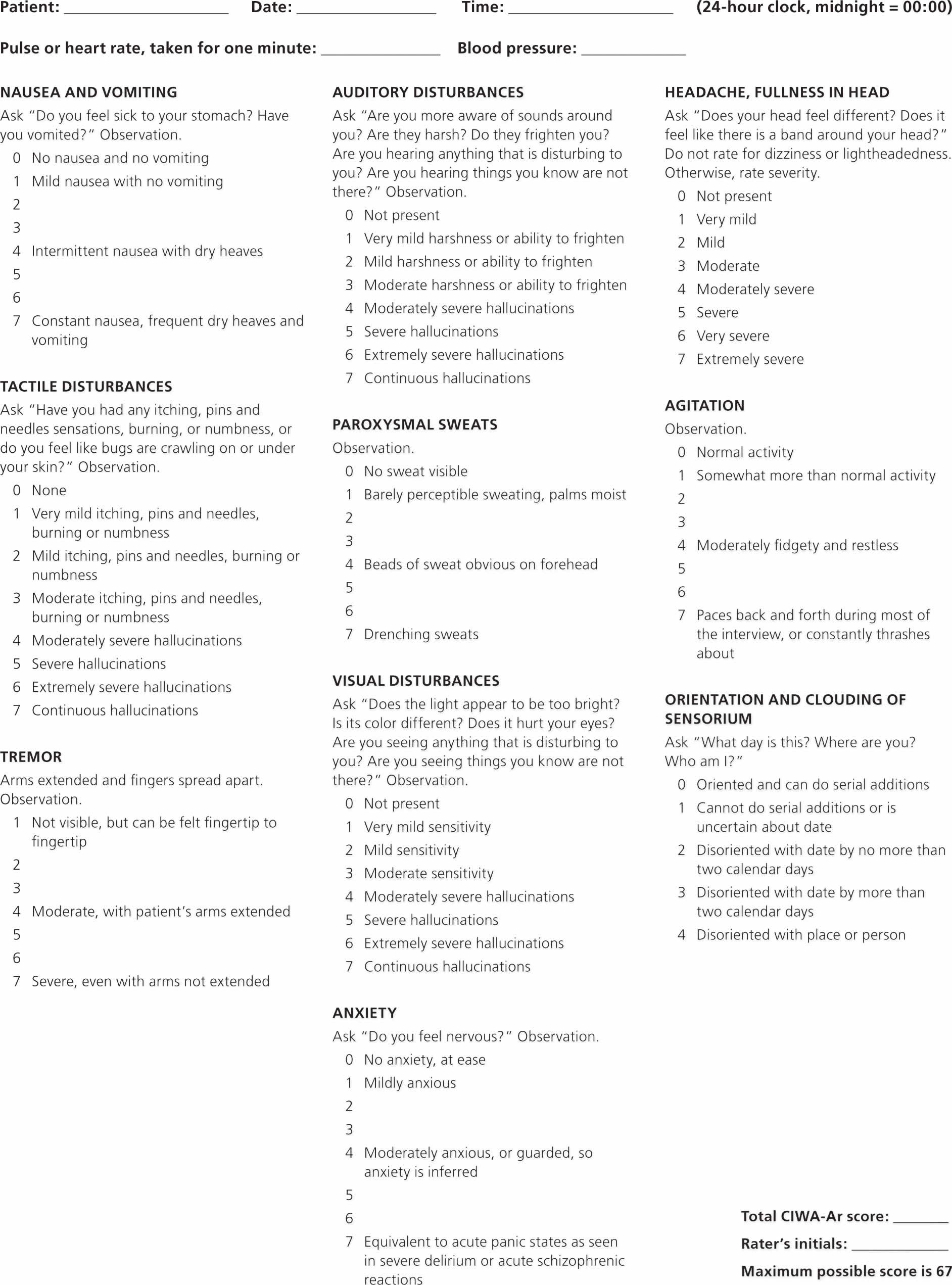

Table 2. Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol – revised (CIWA-Ar) scale

Footnote: Tool to assess the severity of alcohol withdrawal. Absent or very mild ≤ 8 points; mild = 9 to 14 points; moderate = 15 to 20 points; severe > 20 points. Those with a score < 10 do not usually need additional medication.

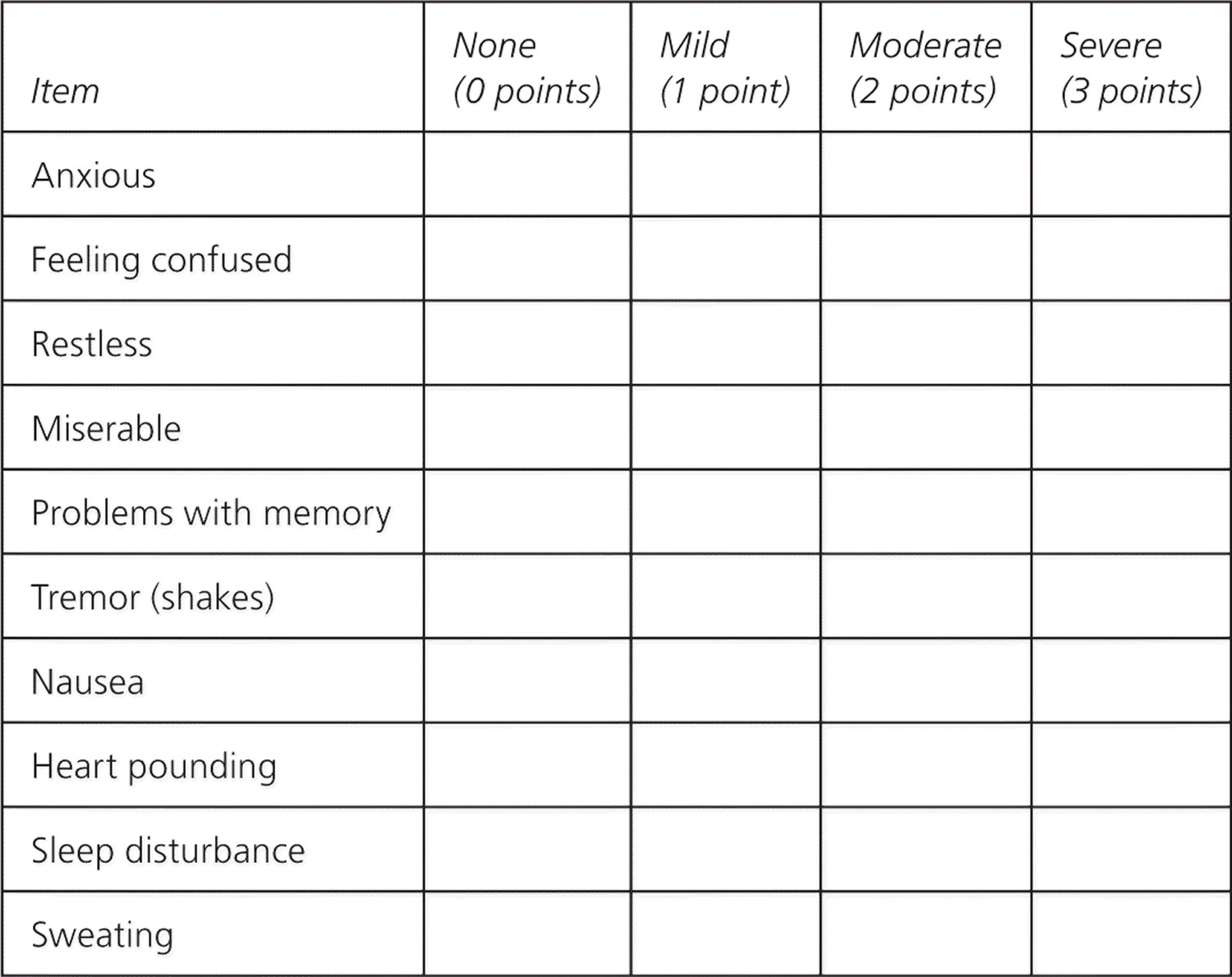

[Source 57 ]Table 3. Short Alcohol Withdrawal Scale (SAWS)

Footnote: Tool to assess the severity of alcohol withdrawal. Patients indicate how they have felt in the previous 24 hours. Mild withdrawal < 12 points; moderate to severe withdrawal ≥ 12 points.

[Source 58 ]Table 4. Luebeck Alcohol withdrawal Risk Scale (LARS)

| Item |

|---|

| LARS 1 |

| Previous inpatient detoxifications (2–5 = 2; 6–10 = 3, ≥11 = 4) |

| Previous outpatient detoxifications (2–5 = 2; 6–10 = 3, ≥11 = 4) |

| Previous withdrawal delirium (≥3 = 3) |

| Previous withdrawal seizures (≥3 = 3) |

| Use of hypnotics during last 2 weeks |

| LARS 2 |

| Daily consumption of alcoholic beverages during last 4 weeks |

| Pattern of steady drinking |

| Frequent sleep disturbances during the last week |

| Nightmares during the last week |

| Malnutrition during last week |

| Multiple vomiting during last week |

| LARS 3 |

| Blood alcohol content (BAC) ° 1 g/l |

| Tremor (despite of BAC ≥1 g/l) |

| Sweating (despite of BAC ≥1 g/l) |

| Pulse rate ≥100/min (despite of BAC ≥1 g/l) |

| Seizure prior or at admission |

| Polyneuropathy |

| Ataxia |

| LARS 4 |

| Sodium (<136 mmol/l) |

| Potassium ( <3.6 mmol/l) |

| Calcium (<2.2 mmol/l) |

| Chloride (<96 mmol/l) |

Footnote: BAC = blood alcohol content

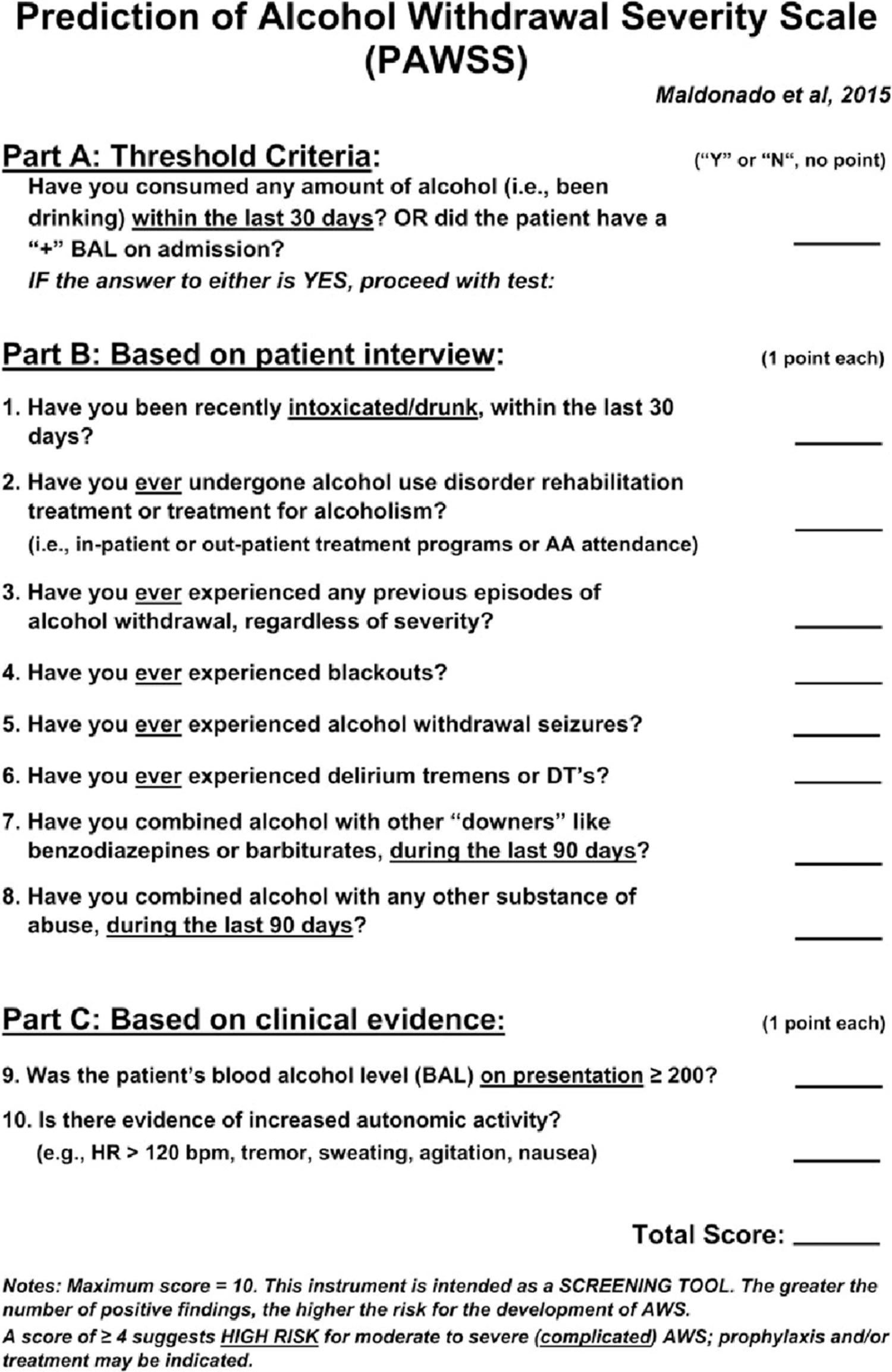

[Source 59 ]Table 5. Prediction of Alcohol Withdrawal Severity Scale (PAWSS)

Footnote: AWS = alcohol withdrawal syndrome

[Source 60 ]Alcohol withdrawal syndrome treatments

Patients in alcohol withdrawal may have numerous potentially life-threatening medical problems 14. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome is a cause of severe discomfort to patients, symptoms are disabling and patients who experienced withdrawal, often are afraid to stop drinking for fear of developing withdrawal symptoms again.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome treatment goal includes:

- Reducing withdrawal symptoms

- Prevent seizures, delirium tremens, and death

- Preventing complications of alcohol use

- Therapy to get you to stop drinking (abstinence from alcohol use)

Treatment goals for patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome are to minimize the severity of symptoms in order to prevent the more severe manifestations such as seizure, delirium and death and to improve the patient’s quality of life 4. Alcohol withdrawal seizures can occur 24 to 72 hours after the last alcohol intake, are typically tonic-clonic, and last less than five minutes. Up to one-third of patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome who have a related seizure will progress to delirium tremens 23. Moreover an effective treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome should be followed by efforts in increasing patient motivation to maintain long-term alcohol abstinence and facilitate the entry into a relapse prevention program 4.

Patients suffering from mild to moderate alcohol withdrawal syndrome can be managed as outpatients while more severe forms should be monitored and treated in an inpatient setting. The availability of an Alcohol Addiction Unit is of help in the clinical evaluation, management, and treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome patients, with a reduction in hospitalization costs. Patients can be managed principally as outpatients and transferred to the inpatient unit only when the clinical situation requires 61. Because alcohol withdrawal syndrome symptoms increase with external stimulation, patients should be treated in a quiet environment. Patients with mild alcohol withdrawal syndrome may only require supportive care 62. Psychological treatment does not reduce the risk of seizures or delirium tremens. Most patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome are prescribed medication, particularly if there is any question about duration of abstinence.

Prophylactic and routine use of thiamine to prevent Wernicke’s encephalopathy:

- Prophylactic thiamine administration is recommended as soon as possible and prior to any carbohydrate load (e.g. intravenous glucose), as glucose intake in the presence of thiamine deficiency can precipitate Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Thiamine should initially be given parentally, as oral thiamine is poorly absorbed through the gastro-intestinal mucosa in people who drink alcohol.

- Administer thiamine 300mg IV per day (diluted in saline over 30 minutes) for 3 days then change to oral 100mg three time per day with meals for at least 5-7 days. Patients with chronic poor nutrition may benefit from extended periods of oral thiamine doses following discharge.

- In the event that the patient presents to hospital but inpatient admission for longer than 2 days is unlikely (e.g. emergency room presentation or 24-48 hour admission), then higher thiamine

doses (e.g. 300mg IV twice a day) may be administered to ensure adequate thiamine dosing. - In the event of poor intravenous access that prevents the recommended regimen, alternative approaches to thiamine dosing should be used. This may include:

- a single intravenous (e.g. 300mg) and high oral doses (e.g. 500mg three time per day) for three days

- once daily intramuscular (e.g. 100mg) dose and high oral doses (e.g. 500mg three time per day) for three days

NOTE: If there is a clinical suspicion of Wernicke’s encephalopathy (e.g. one sign such as confusion, or ataxia or eye signs; or a history of poor nutrition), then consider treating with high dose parenteral thiamine (500mg IV three time per day) as though a diagnosis of Wernicke’s encephalopathy is confirmed.

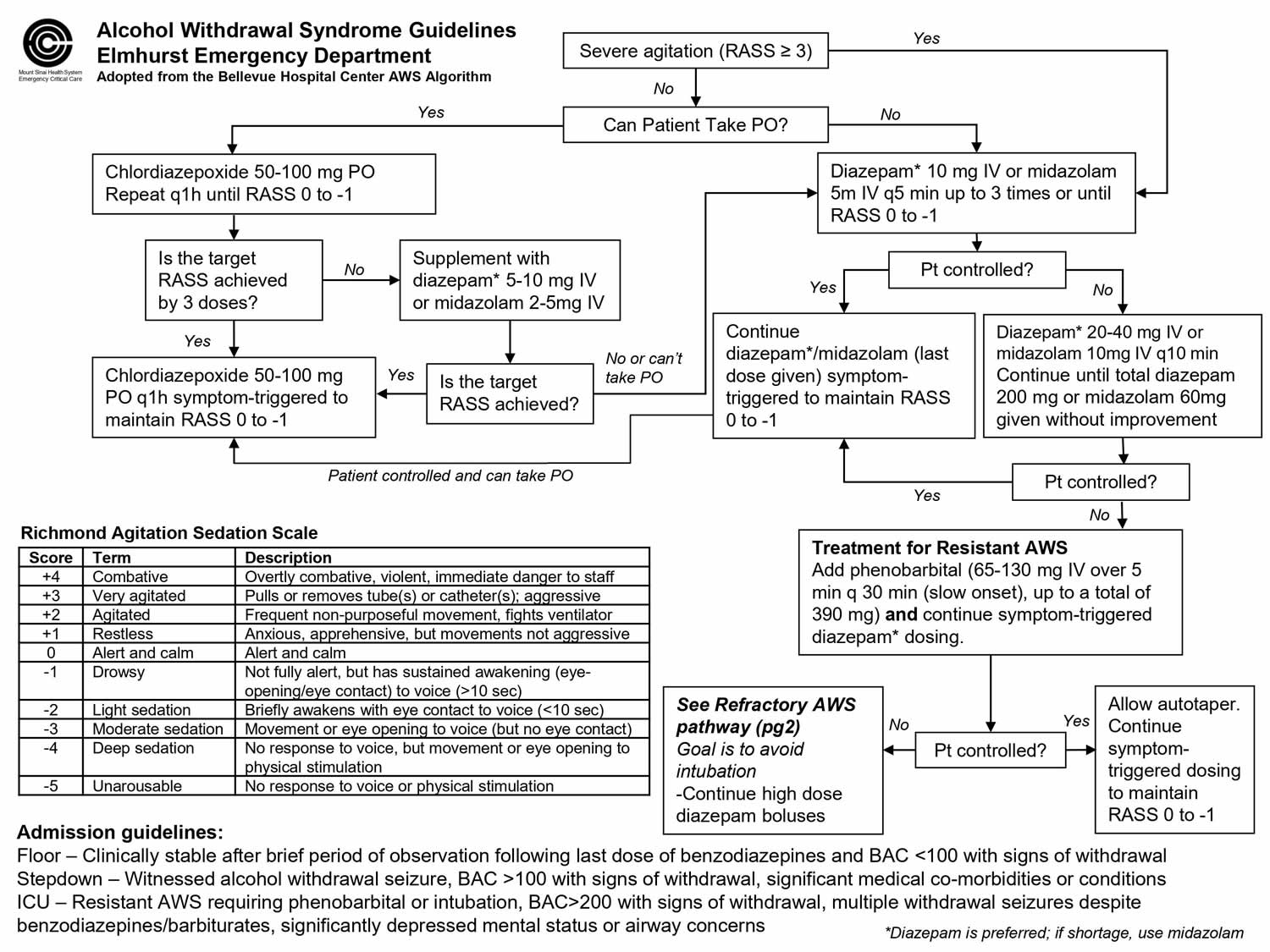

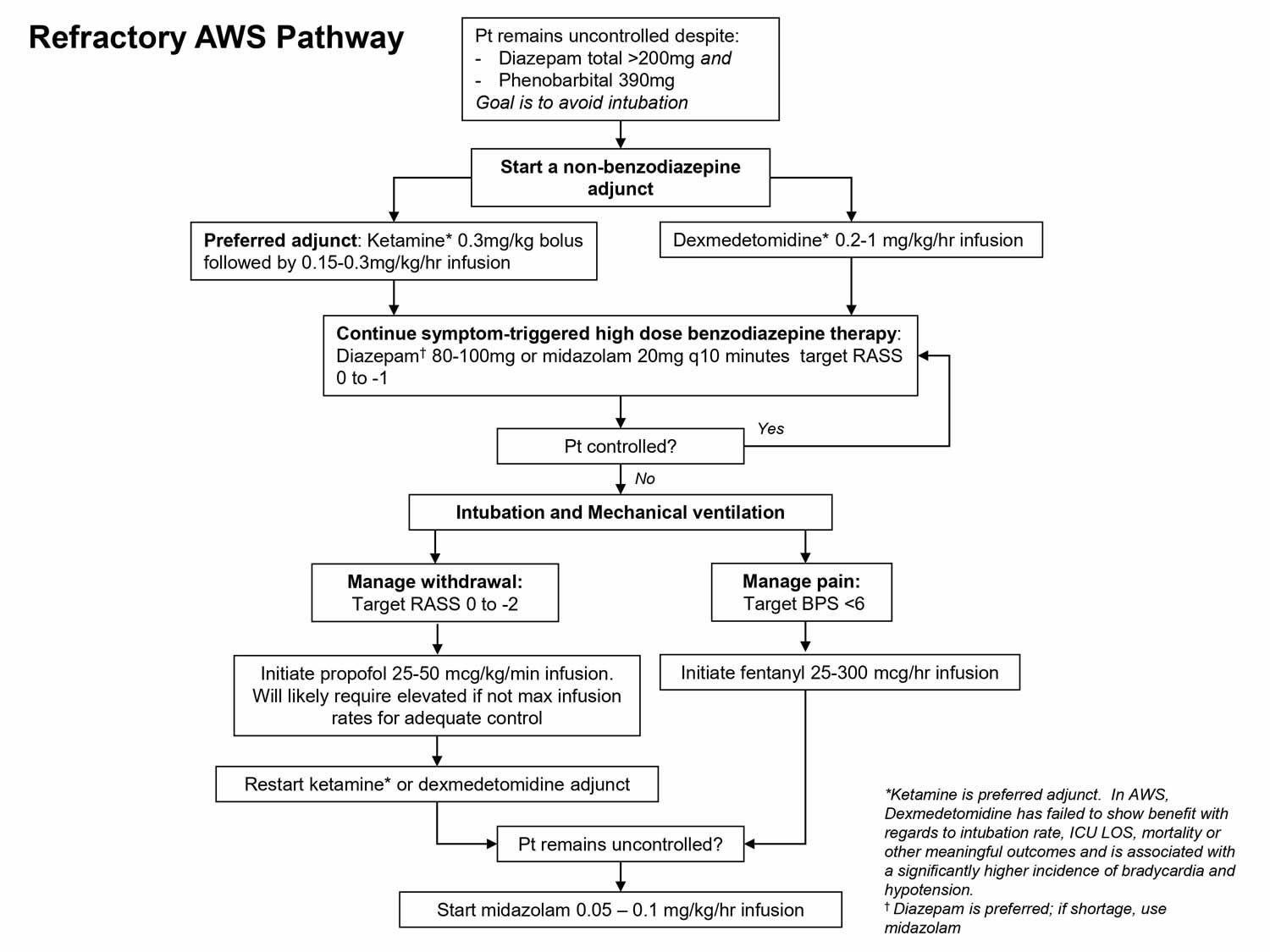

Figure 1. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome guidelines

Footnote: Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) is a medical scale used to measure the agitation or sedation level of a person 63.

Footnote: The refractory alcohol withdrawal syndrome pathway outlines a suggested strategy for those patients in whom adequate control cannot be obtained despite diazepam 200mg and phenobarbital 390mg. In these patients the overall goal is to avoid intubation unless absolutely necessary. The suggested non-benzodiazepine adjunct in this scenario is ketamine, which is more strongly supported by evidence..

INPATIENT TREATMENT

People with moderate-to-severe symptoms of alcohol withdrawal may need inpatient treatment at a hospital or other facility that treats alcohol withdrawal. You will be watched closely for hallucinations and other signs of delirium tremens.

Treatment may include:

- Monitoring of blood pressure, body temperature, heart rate, and blood levels of different chemicals in the body

- Fluids or medicines given through a vein (by IV)

- Sedation using medicines until withdrawal is complete

Administration of intravenous (IV) glucose to patients with seizures is controversial because this is thought to precipitate acute Wernicke encephalopathy in chronic alcoholism unless thiamine (vitamin B1) is also administered. A benzodiazepine can be administered to control seizures. If the patient has hypoglycemia, dextrose 50% in water (D50W) 25 mL to 50 mL and thiamine (vitamin B1) 100 mg intravenously (IV) is also indicated. Low doses of clonidine can help reverse central adrenergic discharge, relieving tachypnea (rapid breathing), tachycardia (fast heart beat), hypertension (high blood pressure), tremor, and craving for alcohol. In an agitated patient, neuroleptics such as haloperidol 5 mg IV or intramuscularly (IM) may be added to sedative-hypnotic agents as an adjunctive therapy. Caution must be taken because haloperidol may decrease the seizure threshold as well as prolong the QT interval.

OUTPATIENT TREATMENT

Outpatient detoxification is an effective, safe, and low-cost treatment for patients with mild to moderate symptoms of alcohol withdrawal syndrome and may allow for less interruption of work and family life 64, 65. During this process, you will need someone who can stay with and keep an eye on you. It is important that caregivers be comfortable with this responsibility 66. Family support can be critical to the success of outpatient treatment. However, family dysfunction or home triggers for alcohol consumption make success unlikely.

You will likely need to make daily visits to your doctor until you are stable. However, patients with serious psychiatric problems (e.g., suicidal ideation, psychosis) or medical conditions should be treated in an inpatient setting 67. Although routine laboratory tests are unnecessary for patients with mild alcohol withdrawal syndrome, significant laboratory abnormalities (e.g., complete blood count, liver function, glucose, or electrolyte testing) would exclude outpatient treatment. Patients with positive results on a urine drug screen, which signifies concurrent drug abuse, should be treated as inpatients. Outpatient treatment requires that the patient be able to take oral medications; is committed to frequent follow-up visits; and has a relative, friend, or other caregiver who can stay with the patient and administer medication 68.

Treatment usually includes:

- Sedative drugs to help ease withdrawal symptoms

- Blood tests

- Patient and family counseling to discuss the long-term issue of alcoholism

- Testing and treatment for other medical problems linked to alcohol use

It is important to go to a living situation that helps support you in staying sober. Some areas have housing options that provide a supportive environment for those trying to stay sober.

Permanent and life-long abstinence from alcohol is the best treatment for those who have gone through alcohol withdrawal.

Contraindications to outpatient treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome

- Coexisting acute or chronic illness requiring inpatient treatment

- Current severe alcohol withdrawal, especially with delirium

- High risk of delirium tremens

- No possibility for follow-up

- No reliable contact person to monitor the patient

- Absence of a support network

- Pregnancy

- Long-term intake of large amounts of alcohol

- Seizure disorder or history of severe alcohol withdrawal seizures

- Suicide risk

- Poorly controlled chronic medical conditions (e.g., diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure)

Relative contraindications

- Coexisting benzodiazepine dependence

- History of unsuccessful outpatient detoxification

- High risk for severe alcohol withdrawal or delirium tremens 69

- Age > 40 years

- Heavy drinking > 8 years

- Drinking > 100 g of ethanol daily (e.g., about one pint of liquor or eight 12-oz cans of beer)

- Symptoms and signs of withdrawal when not drinking

- Random blood alcohol concentration (BAC) > 200 mg per dL

- Elevated mean corpuscular volume

- Elevated blood urea nitrogen (BUN)

- Cirrhosis

Alcoholic hallucinosis treatment

Alcoholic hallucinosis is a rare complication of chronic alcohol abuse characterized by predominantly auditory hallucinations that occur either during or after a period of heavy alcohol consumption 8. Although this condition had been noted for centuries, its classification status is not yet clear 70. Bleuler (1916) termed the condition as alcohol hallucinosis and differentiated it from delirium tremens 70. International Classification of Diseases-10 (ICD-10) relabeled it as Alcohol induced Psychotic Disorder, Predominantly hallucinatory type 71. Usually alcoholic hallucinosis presents with acoustic verbal hallucinations, delusions and mood disturbances arising in clear consciousness and sometimes may progress to a chronic form mimicking schizophrenia.

The pathophysiology of alcohol-related psychosis is unclear. Several hypotheses exist. Some studies suggest that an increase in central dopaminergic activity and dopamine receptor alterations may be associated with hallucinations in patients with alcohol use disorder 72. However, serotonin may also be involved. Other studies imply that amino acid abnormalities may lead to decreased brain serotonin and increased dopamine activity leading to hallucinations. Elevated levels of beta-carbolines and an impaired auditory system have also been associated with alcohol-related psychosis. Neuro-imaging studies have suggested that perfusion abnormalities to various regions in the brain may be associated with the hallucinations in alcohol dependence 73.

Alcoholic hallucinosis treatment is to stabilize the patient paying close attention to airway, breathing and vital signs. If the patient requires sedation due to alcohol-related psychosis, neuroleptics, such as haloperidol, have been considered the first-line medications for treatment 72. Benzodiazepines, such as lorazepam, are used if there is a concern for alcohol withdrawal and seizures. Certain atypical antipsychotics, such as ziprasidone and olanzpine, have also been used to help sedate patients with acute psychosis. Some patients may require the use of physical restraints to protect the patient as well as the staff. Patients with alcohol-related psychosis must also be evaluated for suicidality since it is associated with higher rates of suicidal behaviors. The prognosis for alcohol-related psychosis is less favorable than earlier studies had speculated. However, if the patient can abstain from alcohol, the prognosis is good. If patients are unable to abstain from alcohol, the risk of recurrence is high 74.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome supportive therapy

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome supportive therapy is the first-line approach and, sometimes, the only approach required. It includes frequent reassurance, reality orientation, and nursing care 75. A quiet room without dark shadows, noises, and other excessive stimuli (i.e. bright lights) is recommended 76.

Routine examination should include blood (or breath) alcohol concentration, complete blood count, renal function tests, electrolytes, glucose, liver enzymes, urinalysis and urine toxicology screening. General supportive care should correct fluid depletion, hypoglycemia and electrolytes disturbances, and should include hydration and vitamin supplementation. In particular, thiamine supplementation and B-complex vitamins (including folates) are essential for the prevention of Wernicke’s encephalopathy 77. Thiamine can be given routinely in these patients given the absence of significant adverse effects or contraindications 76. Moreover, since the administration of glucose can precipitate or worsen Wernicke’s encephalopathy, thiamine should be administered before any glucose infusion 78. Finally, with the exception of patients with cardiac arrhythmias, electrolytes disturbances or previous history of alcohol withdrawal syndrome-related seizures, there is no evidence to support the routine administration of magnesium during alcohol withdrawal syndrome 79.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome medication

Because patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome are often nutritionally depleted, thiamine (100 mg daily) and folic acid (1 mg daily) should be used routinely. Thiamine supplementation lowers the risk of Wernicke encephalopathy, which is characterized by oculomotor dysfunction, abnormal mentation, and ataxia.

The treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome requires the use of a long-acting drug as a substitutive agent to be gradually tapered off 80. The ideal drug for alcohol withdrawal syndrome should have a rapid onset and a long duration of action in reducing withdrawal symptoms and a relatively simple metabolism, not depending on liver function. It should not interact with alcohol, should suppress the “drinking behavior” without producing cognitive and/or motor impairment and it should not have a potential for abuse 81.

At present benzodiazepines represent the “gold-standard” in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome (Table 6 and 7) 82. The choice of benzodiazepine in the management of alcohol withdrawal syndrome may be influenced by rapid onset of action for quick agitation control, longer duration of action to lessen potential wearing off and breakthrough symptoms, or shorter duration of action to lessen prolonged sedation in elderly patients or those with compromised hepatic function 83. When given for alcohol withdrawal syndrome, benzodiazepines may be prescribed as either a fixed or symptom-triggered dosing regimen. Studies have shown that symptom-triggered treatment results in a decreased cumulative dose of benzodiazepines and decreased duration of treatment compared with fixed-dose regimens 84. Alternative medications that have been studied for the treatment of acute alcohol withdrawal include valproic acid, carbamazepine, phenobarbital, gabapentin, clonidine, propofol, antipsychotics, dexmedetomidine, and ketamine 16, 85, 86. In particular, phenobarbital, propofol, dexmedetomidine, and ketamine have been investigated extensively as adjuncts to benzodiazepine therapy for benzodiazepine-refractory alcohol withdrawal syndrome in the ICU setting 87, 88, 85.

In severe cases of alcohol withdrawal syndrome or delirium tremens, barbiturates are sometimes prescribed in addition to benzodiazepines. Barbiturates are stronger than benzodiazepines and carry significant risks of extreme sedation, they are normally delivered in intensive care units with close medical monitoring.

Baclofin and gamma‐hydroxybutyric acid (GHB) and sodium oxylate are also sometimes administered during detoxification from alcohol 89.

Medications like dexmedetomidine may be used only in addition to other medications to reduce symptoms like severe agitation, anxiety, and dangerously high blood pressure 89.

When you have completed medically-supervised detox, other medications may be introduced to reduce cravings for alcohol and prevent relapse. The two most effective and commonly prescribed medications are:

- Acamprosate

- Naltrexone: has the unique benefit of reducing the euphoric feelings that accompany alcohol when consumed. It does this by blocking opioid receptors in the brain which contribute to alcohol’s pleasure-causing effects 90.

Other medications that are sometimes used to treat alcoholism are:

- Disulfiram: Antabuse medication that has been approved to treat alcoholism since 1949 91. It blocks the enzyme responsible for metabolizing a toxic component of alcohol. The result is a cluster of undesirable effects (e.g. nausea, vomiting, flushing) that occur when alcohol is consumed.

- Gabapentin and Topiramate: Anti-seizure medications that are prescribed off-label for alcoholism. Both medications are thought to reduce cravings 90.

Table 6. Oral medications used to treat alcohol withdrawal syndrome

| Medication | Typical single dose | Common adverse effects | Contraindications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzodiazepines | |||

| Chlordiazepoxide (Librium) | 25 to 50 mg | Sedation, fatigue, respiratory depression, retrograde amnesia, ataxia, dependence and abuse | Hypersensitivity to drug/class ingredient, severe hepatic impairment, avoid abrupt withdrawal |

| Diazepam (Valium) | 10 mg | ||

| Lorazepam (Ativan) | 2 mg | ||

| Oxazepam | 15 to 30 mg | ||

| Anticonvulsants | |||

| Carbamazepine (Tegretol) | 600 to 800 mg | Dizziness, ataxia, diplopia, nausea, vomiting | Hypersensitivity to drug/class ingredient, hypersensitivity to tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitor use within the previous 14 days, hepatic porphyria |

| Gabapentin (Neurontin) | 300 to 600 mg | ||

| Oxcarbazepine (Trileptal) | 450 to 900 mg | ||

| Valproic acid (Depakene) | 1,000 to 1,200 mg | ||

| Beta blocker | |||

| Atenolol (Tenormin) | Pulse 50 to 79 beats per minute: 50 mg | Bradycardia, hypotension, fatigue, dizziness, cold extremities, depression | Hypersensitivity to drug/class ingredient, second- or third-degree atrioventricular block, uncompensated heart failure, cardiogenic shock, sick sinus syndrome without implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, untreated pheochromocytoma |

| Pulse ≥ 80 beats per minute: 100 mg | |||

| Alpha-adrenergic agonist | |||

| Clonidine (Catapres) | 0.2 mg | Hypotension, dry mouth, dizziness, constipation, sedation | Hypersensitivity to drug/class ingredient |

Footnote: These medications should not be stop suddenly.

[Source 92 ]Benzodiazepines

At present benzodiazepines represent the “gold-standard” in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome (Table 7) 82. Furthermore, benzodiazepines represent the only class of medications with proven efficacy in preventing the development of complicated forms of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, with a reduction in the incidence of seizures (84%), delirium tremens and the associated risk of mortality 93. However, the use of benzodiazepines is associated with increased risk of excessive sedation, motor and memory deficits and respiratory depression, and these effects are more pronounced in patients with liver impairment 82. Moreover the risk of abuse and dependence 94 limits benzodiazepine use in alcohol dependent patients 82.

In the United States, the only benzodiazepines that are approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome are chlordiazepoxide and diazepam; however, other benzodiazepines are often used because no single agent has proven superior to the others 95. While in Europe, clomethiazole is also widely used 82. The efficacy of benzodiazepines in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome seems to be mediated by their stimulation of GABAA receptors with alcohol mimicking effects 80.

Certain people make better candidates than others to treat alcohol withdrawal symptoms with benzodiazepines. Those who can benefit the most are those who 96:

- Have a diagnosable anxiety disorder, such as panic disorder or social anxiety, that would interfere with their ability to participate in recovery treatment

- Have trouble falling asleep or staying asleep or not sleeping for long periods

- Have withdrawal symptoms such as agitation, insomnia, tremors, seizures, or convulsions

- Have post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms

No study has shown a clear superiority of any agent over the others. The greater evidence exists for the long-acting agents (chlordiazepoxide and diazepam) 97, given their ability to produce a smoother withdrawal 7. The clinical effect is mediated by the drug (benzodiazepine) per se, and by its active metabolites produced by phase 1 liver oxidation. Subsequently all products of oxidative metabolism are inactivated by phase 2 liver glucuronidation and excreted 98. However, in patients with reduced liver metabolism, such as in the elderly or in those with advanced liver disease, the use of short-acting agents may be preferred in order to prevent excessive sedation and respiratory depression 93. In these cases, oxazepam and lorazepam represent the drugs of choice due to the absence of oxidative metabolism and active metabolites (see Table 7) 99.

The possibility of multiple administration routes (oral, intramuscular [I.M.], or intravenous [I.V.]) represents an advantage of benzodiazepines. The intravenous (IV) route should be preferred for moderate to severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome because of the rapid onset of action, while the oral route can be used in the milder forms. Chlorodiazepoxide and diazepam should not be administered intramuscular (IM) due to their erratic absorption; lorazepam can be administered by all three routes; oxazepam can be administered only orally, while midazolam can be given intravenously as continuous infusion 7.

A “fixed-dose”, rather than a “loading dose” or a “symptoms-triggered” regimen can be adopted for the management of alcohol withdrawal syndrome (Table 7).

- Fixed-Dose Treatment Regimen

- Medical staff breaks the total dose into four smaller amounts with fixed-dose treatments. For example, if a doctor prescribed 40 mg benzodiazepines a day, the doses are given in 10 mg doses four times a day (i.e. diazepam 10 mg four times per day for 1 day, then 5 mg four times per day for 2 days, then tapering off; alternatively chlordiazepoxide 50–100 mg four times per day for 1 day, then 25–50 mg four times per day for 2 days, with subsequent tapering off). With the fixed-dose approach, the chosen drug is given at regular intervals (independently from patient’s symptoms), tapering off the dose by 25% per day from day 4 to day 7. Additional doses can be administered if symptoms are not adequately controlled. This approach is highly effective and could be preferred in those patients at risk for severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome, or in those patients with history of seizures or delirium tremens. However patients should be monitored for the risk of excessive sedation and respiratory depression 97.

- This regimen is helpful in outpatient or inpatient treatment settings 100.

- Loading-Dose Treatment Regimen

- Loading-dose regimens involve doctors administering a moderate-to-high dose of a long-acting benzodiazepine (i.e. diazepam 10–20 mg or chlordiazepoxide 100 mg, every 1–2 hours) in two-hour intervals in order to produce sedation; successively, drug levels will decrease (auto-taper) through metabolism. The risk of benzodiazepine toxicity is high during the early phase of the treatment and the patient requires a strict clinical monitoring to prevent benzodiazepine toxicity. However, this approach seems to produce the shorter treatment course secondary to the progressive auto-tapering of drug levels and to reduce the incidence of severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome promoting recovery from alcohol withdrawal syndrome 97..

- Close monitoring by medical staff includes checking the severity level of withdrawal symptoms. This regimen works best in an inpatient environment.

- Symptom-Triggered Treatment Regimen

- The last scheme, symptom-triggered, is based on the administration of the chosen drug (diazepam 5–20 mg, chlordiazepoxide 50–100 mg or lorazepam 2–4 mg) if the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Revised (CIWA-Ar) score is >8–10. Symptom severity is measured hourly. The dose is adjusted (i.e. from 5 to 10 mg of diazepam) according to the severity of the symptoms and can be repeated every hour until the CIWA-Ar score decreases to <8 80. The use of the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Revised (CIWA-Ar) score seems to be useful and effective in the dose-adjustment of the drug.

- Monitoring trigger symptoms of alcohol withdrawal should take place in an inpatient medical detox. As triggers occur, medical staff administer benzodiazepines. This method can decrease a person’s time in medical detox.

- However, if someone has a history of seizures or other complications of medical detox, this regimen is considered too high-risk for potential seizure activity 100.

Trials comparing different alcohol withdrawal syndrome treatment strategies did not find clear evidence of the superiority for one of these regimens 101. However, the symptom-triggered regimen has been shown to reduce total benzodiazepine consumption and treatment duration with respect to fixed-dose in patients at low risk for complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome 102.

From a practical point of view, in an inpatients setting in which an intensive care unit (ICU) is rapidly available the front-loading scheme could be safely chosen. On the contrary, if ICU is not available but a strict clinical observation is possible, symptom-triggered regimen could be preferred in order to reach the clinical effect with the minimum benzodiazepine administration. The fixed-dose treatment represents the recommended regimen in those patients at risk for complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome, with history of seizures or delirium tremens (in whom drugs should be administered regardless of the symptoms) 7.

Treatment of delirium tremens requires the use of benzodiazepines as primary drugs, with the possible use of neuroleptics to control psychosis and dysperceptions.

Table 7. Benzodiazepines used to treat alcohol withdrawal syndrome

| DRUG | HALF-LIFE | ACTIVE METABOLITES | METABOLISM | EXCRETION |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diazepam | 20–80 hours (metabolites 30- 100 hours) | Yes | Hepatic | Hepatic – urinary (metabolites) |

| Chlordiazepoxide | 5–30 hours (metabolites 30- 200 hours) | Yes | Hepatic | Hepatic – urinary (metabolites) |

| Lorazepam | 10–20 hours | No | Hepatic | Urinary, fecal |

| Oxazepam | 10–20 hours | No | Hepatic | Urinary |

| Midazolam | 2–6 hours | Yes | Hepatic, Gut | Urinary |

Table 8. Fixed and Symptom-Triggered Benzodiazepine dosing for oral alcohol withdrawal medications

| Medication | Fixed schedule | Symptom-triggered schedule* |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | ||

| Diazepam (Valium) | 10 mg every 6 hours | 10 mg every 4 hours |

| Chlordiazepoxide (Librium) | 25 to 50 mg every 6 hours | 25 to 50 mg every 4 hours |

| Lorazepam (Ativan) | 2 mg every 8 hours | 2 mg every 6 hours |

| Day 2 | ||

| Diazepam | 10 mg every 8 hours | 10 mg every 6 hours |

| Chlordiazepoxide | 25 to 50 mg every 8 hours | 25 to 50 mg every 6 hours |

| Lorazepam | 2 mg every 8 hours | 2 mg every 6 hours |

| Day 3 | ||

| Diazepam | 10 mg every 12 hours | 10 mg every 6 hours |

| Chlordiazepoxide | 25 to 50 mg every 12 hours | 25 to 50 mg every 6 hours |

| Lorazepam | 1 mg every 8 hours | 1 mg every 8 hours |

| Day 4 | ||

| Diazepam | 10 mg at bedtime | 10 mg every 12 hours |

| Chlordiazepoxide | 25 to 50 mg at bedtime | 25 to 50 mg every 12 hours |

| Lorazepam | 1 mg every 12 hours | 1 mg every 12 hours |

| Day 5 | ||

| Diazepam | 10 mg at bedtime | 10 mg every 12 hours |

| Chlordiazepoxide | 25 to 50 mg at bedtime | 25 to 50 mg every 6 hours |

| Lorazepam | 1 mg at bedtime | 1 mg every 12 hours |

Footnote: *For patients with a SAWS (Short Alcohol Withdrawal Scale) score ≥ 12, or CIWA-Ar (Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol, Revised) score > 9.

[Source 92 ]Benzodiazepines side effects

All drugs, including benzodiazepines, have the potential for adverse effects. Some who are taking the medication for alcoholism will not have any side effects. Many factors other than the drug play a role in how it reacts with the body. A few examples are allergies, underlying medical conditions, and interactions with other medicines.

Some of the most common side effects of benzodiazepines include 103:

- Breathing issues

- Drowsiness

- Disorientation

- Impaired motor skills

- Drop in blood pressure that may cause a loss of consciousness

- Digestive problems

There are contraindications or times when taking benzodiazepines could result in dangerous or toxic reactions. For example, during pregnancy taking benzodiazepines could lead to congenital malformations 103.

More severe, yet rare, side effects can occur with benzodiazepine toxicity. Complications can lead to 104:

- Food, saliva, liquids, or vomit is breathed into the lungs rather than into the stomach, also called aspiration pneumonia

- Respiratory arrest

- A breakdown of muscle tissue that leaks proteins that can damage kidneys into the blood is also called rhabdomyolysis.

Fortunately, there is a medicine that can reverse the adverse effects of benzodiazepines, flumazenil if toxicity or overdose occurs 104.

Who should not take benzodiazepines for alcohol withdrawal?

Warnings for doctors regarding benzodiazepines as alcohol withdrawal medication include considering other medication for patients who 105:

- Are pregnant or breastfeeding

- Are allergic to any of the ingredients of the medicine

- Are taking other central nervous system depressants, including illicit use

- Have respiratory illness or disease

- Have certain medical problems such as liver or kidney disease

- Have a nervous system disorder

- Have severe depression or suicidal ideation

- Are elderly

Benzodiazepines are also contraindicated for anyone taking them for another condition or taking other medication for alcoholism.

Barbiturates and propofol

The use of barbiturates in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome has been limited given their narrow therapeutic window, the risk of excessive sedation and the interference with the clearance of many drugs 76. However, in the setting of ICU, in those patients requiring high doses of benzodiazepines to control alcohol withdrawal syndrome symptoms or developing delirium tremens, barbiturates maintain a specific indication. The combination of phenobarbital with benzodiazepines promotes benzodiazepine binding to the GABAA receptor, possibly increasing the efficacy of the benzodiazepine action 106. In patients affected by severe delirium tremens requiring mechanical ventilation, the combination of benzodiazepines and barbiturates produces both a decrease in the need of mechanical ventilation and a trend towards a decrease in ICU length of stay 86.

Propofol enhances the inhibitory effects at the GABAA receptor and decreases excitatory circuits of the NMDA transmitter system. Due to its strong lipophilic properties, it features a rapid onset of action and is easy to titrate because of the short half‐life that allows a rapid evaluation of patient’s mental status after discontinuation 107. Propofol has general anesthetic effects that often require intubation and mechanical ventilation. Its use is therefore restricted to the intensive care unit (ICU) making this agent an adjunct therapy for refractory cases of alcohol withdrawal syndrome 108, 109. These characteristics make propofol a useful therapeutic option in patients with severe delirium tremens, who are poorly controlled with high doses of benzodiazepines 110. However, the use of this drug requires clinical monitoring, endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation. In the setting of ICU, in those patients requiring sedation and mechanical ventilation, the Sedation-Agitation Scale (SAS) or the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) can be used to titrate sedation 86. Its application and experience in alcohol withdrawal syndrome is limited to only a few cases and rebound of withdrawal symptoms soon after stopping propofol infusion has been reported 100.

Alpha2-agonists, beta-blockers and neuroleptics

These classes of medications have been tested and are currently used as adjunctive treatment for alcohol withdrawal syndrome. However, the lack of efficacy in preventing severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome and the risk of masking alcohol withdrawal syndrome symptoms make these drugs not recommended as monotherapy. They should be used only as adjunctive treatment, in patients with co-existing comorbidities, and to control neuro-autonomic manifestations of alcohol withdrawal syndrome when not adequately controlled by benzodiazepines administration.

The administration of these drugs as monotherapy could mask alcohol withdrawal syndrome symptoms and reduce the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol Revised (CIWA-Ar) scores with a consequent reduction of the prescription of benzodiazepines and possible risk to develop complicated alcohol withdrawal syndrome.

Beta-blockers (e.g. atenolol) could be used to treat hyperarousal symptoms in patients with coronary artery disease 1. However, given their effect on tremors, tachycardia and hypertension, these drugs could mask alcohol withdrawal syndrome symptoms and should be considered only in conjunction with benzodiazepines in patients with persistent hypertension or tachycardia 82.

The use of alpha2-agonists could have a role in the management of alcohol withdrawal syndrome. Parenteral administration of clonidine may be associated with sedation and other side effects, while low doses of clonidine (oral, transdermal) may have a role in the control of alcohol withdrawal syndrome symptoms via a reduction of autonomic hyperactivity (hypertension and tachycardia) 111. The use of dexmedetomidine, a more selective alfa2-receptor agonist, showed interesting results in controlling sympathetic symptoms with less sedation than clonidine as adjunctive drug to lorazepam for severe alcohol withdrawal syndrome, and with a possible benzodiazepine-sparing effect. However, bradycardia was a commonly observed side-effect. Moreover, these results require further investigations and validation 112.

Neuroleptics (i.e., haloperidol) are generally used for the management of hallucinosis and delirium. However, given their lack of effect in preventing the worsening of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, their facilitating effect on the development of seizures and the risk of QT prolongation, the use of neuroleptic agents as monotherapy is contraindicated. Moreover they are associated with a longer duration of delirium, higher complication rate and higher mortality 83. The use of neuroleptics should be reserved as adjunctive treatment in the case of agitation, perceptual disturbances, or disturbed thinking not adequately controlled by benzodiazepines 82.

Carbamazepine

Carbamazepine is a tricyclic anticonvulsant able to produce a GABAergic effect and to block NMDA receptors 113. It has been shown to be an effective drug in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, at least in mild to moderate forms, producing an effect superior to placebo and non-inferior to benzodiazepines 113. The proposed treatment scheme is 600–800 mg/day on day 1, tapered down to 200 mg over 5 days 114. A reduction of alcohol relapse has also been showed in the post-alcohol withdrawal syndrome phase 115. However, side effects associated with long-term administration (i.e. nausea, vomiting, dermatitis, Steven-Johnson syndrome, agranulocitosis) could limit its extensive use. Moreover, given its drug-drug interaction potential, this drug may be difficult to manage in patients with in patients with multiple comorbidities and treated with other medications 116. Oxcarbazepine (900 mg for 3 days, 450 mg for 4th day, 150 mg for 5th day), a metabolite of carbamazepine, due to the only weak induction of Cytochrome P450 and the kidney excretion, could represent a valid alternative to carbamazepine 4. However its role in alcohol withdrawal syndrome remains to be completely demonstrated.

Valproate