Alternating hemiplegia of childhood

Alternating hemiplegia of childhood is a neurological condition that usually affects children before 18 months of age that is characterized by recurrent episodes of temporary paralysis, often affecting one side of the body (hemiplegia) or both sides of the body, multiple limbs, or a single limb. During some episodes, the paralysis alternates from one side of the body to the other or affects both sides at the same time. These episodes begin in infancy or early childhood, usually before 18 months of age, and the paralysis lasts from minutes to several days. A characteristic feature of alternating hemiplegia of childhood is that symptoms disappear during sleep and return upon waking. Many affected children display some degree of developmental delay, abnormal eye (oculomotor) movements, uncontrolled limb movements (including ataxia, dystonia, and choreoathetosis) and seizures.

In addition to paralysis, affected individuals can have sudden attacks of uncontrollable muscle activity; these can cause involuntary limb movements (choreoathetosis), muscle tensing (dystonia), movement of the eyes (nystagmus), or shortness of breath (dyspnea). People with alternating hemiplegia of childhood may also experience sudden redness and warmth (flushing) or unusual paleness (pallor) of the skin. These attacks can occur during or separately from episodes of hemiplegia.

The episodes of hemiplegia or uncontrolled movements can be triggered by certain factors, such as stress, extreme tiredness, cold temperatures, or bathing, although the trigger is not always known. A characteristic feature of alternating hemiplegia of childhood is that all symptoms disappear while the affected person is sleeping but can reappear shortly after awakening. The number and length of the episodes initially worsen throughout childhood but then begin to decrease over time. The uncontrollable muscle movements may disappear entirely, but the episodes of hemiplegia occur throughout life.

Alternating hemiplegia of childhood also causes mild to severe cognitive problems. Almost all affected individuals have some level of developmental delay and intellectual disability. Their cognitive functioning typically declines over time.

Alternating hemiplegia of childhood is a rare condition that affects approximately 1 in 1 million people 1.

The majority of cases of alternating hemiplegia of childhood are caused by a new change (called a mutation or pathogenic variant) in the ATP1A3 gene that is not inherited. Thus, most patients with alternating hemiplegia of childhood do not have a family history of the disorder. A small number of cases of alternating hemiplegia of childhood are caused by changes in the ATP1A2 gene 2. When this condition does run in families, it follows an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance 1. Treatment is limited to therapies that can help reduce the severity and duration of symptoms. Drug therapy including verapamil may help to reduce the severity and duration of attacks of paralysis associated with the more serious form of alternating hemiplegia 2.

Alternating hemiplegia of childhood causes

Alternating hemiplegia of childhood is primarily caused by mutations in the ATP1A3 gene. Very rarely, a mutation in the ATP1A2 gene is involved in the condition. These genes provide instructions for making very similar proteins. They function as different forms of one piece, the alpha subunit, of a larger protein complex called Na+/K+ ATPase; the two versions of the complex are found in different parts of the brain. Both versions play a critical role in the normal function of nerve cells (neurons). Na+/K+ ATPase transports charged atoms (ions) into and out of neurons, which is an essential part of the signaling process that controls muscle movement.

Other genes which cause alternating hemiplegia of childhood or a disorder with similar symptoms include the CACNA1A, SLC1A3, and ATP1A2 in less than 1% of patients.

Mutations in the ATP1A3 or ATP1A2 gene reduce the activity of the Na+/K+ ATPase, impairing its ability to transport ions normally. It is unclear how a malfunctioning Na+/K+ ATPase causes the episodes of paralysis or uncontrollable movements characteristic of alternating hemiplegia of childhood.

Alternating hemiplegia of childhood inheritance pattern

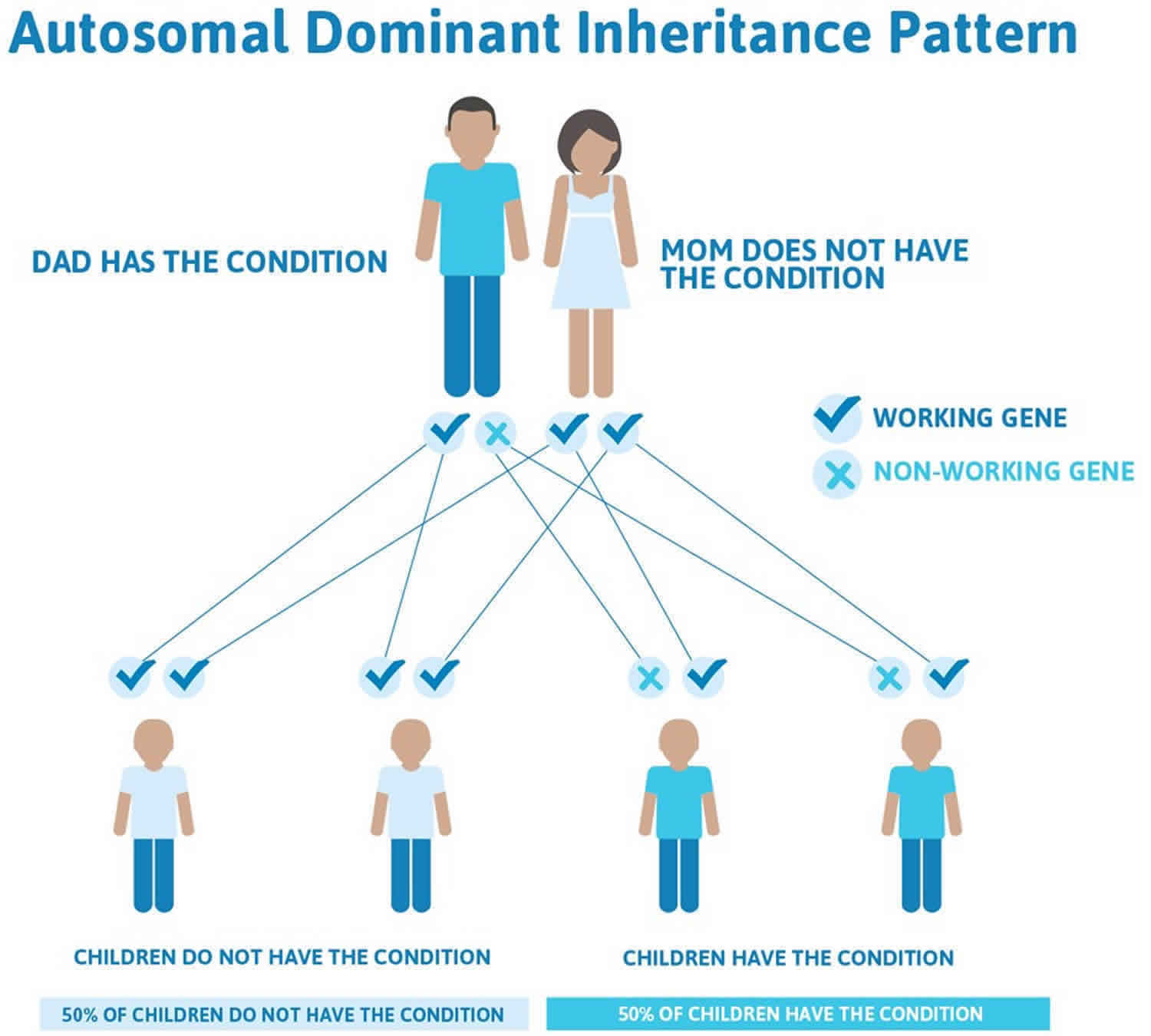

Alternating hemiplegia of childhood is considered an autosomal dominant condition, which means one copy of the altered gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the disorder. Most cases of alternating hemiplegia of childhood result from new mutations in the gene and occur in people with no history of the disorder in their family. However, alternating hemiplegia of childhood can also run in families. For unknown reasons, the signs and symptoms are typically milder when the condition is found in multiple family members than when a single individual is affected.

Figure 1. Alternating hemiplegia of childhood autosomal dominant inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Alternating hemiplegia of childhood symptoms

Alternating hemiplegia of childhood is a highly variable and unpredictable disorder and the specific symptoms and severity of the disorder can vary greatly from one person to another. Some individuals may have mild forms of the disorder with a good prognosis, and develop almost normally. However, others may have a severe form with the potential for serious and disabling complications that can disrupt various aspects of life and manifest as persistent neurologic disability.

It is important to note that affected individuals may not have all of the symptoms discussed below. Affected individuals should talk to their physician and medical team about their specific case, associated symptoms and overall prognosis. Symptoms usually develop before 18 months of age.

The most prominent symptom is repeated episodes of weakness or paralysis affecting one side of the body at a time in an alternating fashion (alternating hemiplegia or hemiparesis). Weakness or paralysis may also sometimes affect both sides of the body (quadriplegia) or rapidly transition from one side to the other. These episodes typically last for minutes to hours, but in some children under certain circumstances can persist for several days or even weeks in some cases. They may occur daily, weekly or once every few months. In some individuals one side of the body is affected more than the other. In episodes when both sides are involved, one side may recover more quickly than the other. The face may be spared during an episode, but weakness of facial muscles (facial paresis) can occur with mouth deviation, slurred speech, and difficulty swallowing. The intensity of individual episodes varies as well and can range from numbness to a complete loss of feeling and movement. Episodes often begin to appear in early infancy, and sometimes even in the first few days of life.

During an episode, affected individuals usually remain alert and may be able to communicate verbally. A unique aspect of these episodes is that they cease when sleeping and may not resume for approximately 15-20 minutes upon waking. In severe, prolonged cases, this window of time may allow affected individuals to eat and drink. Episodes can become worse over time and, in severe cases, can make walking unassisted difficult. Some affected individuals may feel tired or unwell shortly before a hemiplegic episode occurs.

Some individuals with alternating hemiplegia of childhood may also have additional neurologic symptoms that may occur isolated from or during hemiplegic episodes. These symptoms include sudden, dance-like, involuntary movements of the limbs and facial muscles (choreoathetosis), difficulty breathing (dyspnea), difficulty coordinating muscles (ataxia) causing walking and balance problems, and dystonia. Dystonia is a general term for a group of muscle disorders generally characterized by involuntary muscle contractions that force the body into abnormal, sometimes painful, movements and positions (postures). Dystonic attacks can involve the tongue potentially causing breathing and swallowing difficulties.

During these episodes, some affected individuals may experience dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system, which regulates certain involuntary body functions such as heart rate, blood pressure, sweating, and bowel and bladder control. Symptoms associated with autonomic dysfunction can vary greatly, but may include excessive or lack of sweating, changes in body temperature, skin discoloration, altered pain perception and gastrointestinal problems. Cardiorespiratory problems such as a slow heartbeat (bradycardia), a high-pitched wheezing (stridor), sudden constriction of the walls of the tiny airway branches called bronchioles (bronchospasm), and difficulty breathing or gasping for breath may also develop.

The characteristic episodes that define alternating hemiplegia of childhood are not epileptic in nature, although are frequently mistaken for epileptic seizures early in life. However, 50% or more of affected individuals develop epilepsy as they get older. Epileptic seizures typically occur much less frequently than hemiplegic episodes, but when they do, may result in status epilepticus, or persistent seizure activity requiring medical intervention. Epilepsy in children with alternating hemiplegia of childhood is often treated with standard antiepileptic medications, but may sometimes prove resistant to traditional epilepsy treatments (intractable epilepsy).

Some infants and children with alternating hemiplegia of childhood exhibit developmental delays. In addition, some children who experience prolonged, recurrent episodes may develop slowly progressive neurological problems including loss of previously acquired skills (psychomotor regression) and cognitive impairment. Behavioral or psychiatric issues such as impulsivity, short-temperedness, poor communication and poor concentration may also occur. Some affected children may have learning disabilities and issues with skills that require movement and coordination (dyspraxia).

A common, frequent type of spell in infants with alternating hemiplegia of childhood results in irregular eye movements including rapid, involuntary, “jerking” eye movements that may be side to side, up and down or rotary (episodic nystagmus). Nystagmus often affects only one eye (monocular). In some patients, these irregular eye movements are the first noticeable symptom of alternating hemiplegia of childhood, but they often go unrecognized, or are considered most likely to represent seizure activity. Some affected individuals may intermittently appear crossed-eyed, where the eyes are misaligned either outward (exotropia) or inward (esotropia). With exotropia, one eye drifts outward toward the ear, while the other eye faces straight ahead. With esotropia, one eye drifts inward toward the nose, while the other eye faces straight ahead.

Alternating hemiplegia of childhood diagnosis

A diagnosis of alternating hemiplegia of childhood is based upon identification of characteristic symptoms, a detailed patient history, a thorough clinical evaluation and a variety of specialized tests. Specific diagnostic criteria have been proposed for alternating hemiplegia of childhood. The seven criteria are:

- Onset of symptoms before 18 months;

- Repeated episodes of hemiplegia that sometimes involve both sides of the body;

- Quadriplegia that occurs as an isolated incident or as part of a hemiplegic attack;

- Relief from symptoms upon sleeping;

- Additional paroxysmal attacks such as dystonia, tonic episodes, abnormal eye movements or autonomic dysfunction;

- Evidence of developmental delay or neurological abnormalities such as choreoathetosis, ataxia or cognitive disability;

- Cannot be attributed to another cause.

Clinical testing and work-up

A diagnosis of alternating hemiplegia of childhood is primarily one of exclusion. A wide variety of specialized tests may be used to rule out other conditions. Such tests include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), and magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS). An MRI uses a magnetic field and radio waves to produce cross-sectional images of particular organs and bodily tissues such as brain tissue. An MRA, images are produced to evaluate the blood vessels. An MRS is used to detect metabolic changes in the brain and other organs.

Additional tests may include electroencephalogram (EEG), which measures electrical responses in the brain, and is typically used to identify epilepsy; metabolic screening to detect urine organic acids, which is indicative of certain metabolic disorders; studies of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which can exclude neurotransmitter deficiency disorders with similar episodic oculomotor abnormalities; erythrocyte sedimentation rates, which measures how long it takes red blood cells to settle in a test tube over a given period to detect inflammatory disorders; and hypercoagulable studies to detect disorders with a predisposition to forming blood clots.

Molecular genetic testing for mutations in the ATP1A3 gene is available on a clinical basis via individual targeted gene sequencing or as part of larger gene panels. Increasingly, ATP1A3 mutations are identified in the context of clinical exome sequencing.

Alternating hemiplegia of childhood treatment

No specific therapy exists for individuals with alternating hemiplegia of childhood. Treatment is directed toward the specific symptoms apparent in each individual. Treatment may require the coordinated efforts of a team of specialists. Pediatricians, pediatric neurologists, neurologists, ophthalmologists, and other healthcare professionals may need to systematically and comprehensively plan an affected child’s treatment. Because alternating hemiplegia of childhood is highly variable, an individualized treatment program needs to be devised for each child. The effectiveness of current therapies for alternating hemiplegia of childhood will vary greatly among affected individuals. What is effective for one person may not be effective for another.

Treatment is generally focused on trying to reduce the frequency and severity of the characteristic episodes and the management of episodes when they occur. Triggers include psychological stress/excitement; environmental stressors (e.g., bright light, excessive heat or cold, excessive sound, crowds); water exposure (e.g., bathing, swimming); certain foods or odors (e.g., chocolate, food dyes, missed meals); excessive or atypically strenuous exercise; illness; irregular sleep (missing a nap, delayed bedtime. Avoiding triggers to the extent possible is recommended for individuals with alternating hemiplegia of childhood. In addition, long-term drug therapy may be recommended to help lessen the frequency of episodes.

A medication which has proved effective in reducing the frequency or severity of episodes in some individuals is a drug called flunarizine, a drug with calcium channel blocking properties. Flunarizine is given as a preventive (prophylactic) agent and has lessened the frequency, duration and severity of non-epileptic episodes in some individuals with alternating hemiplegia of childhood. Flunarizine is not readily available in the US. However, flunarizine is available in other countries for the treatment of migraine and other neurological symptoms.

Anti-seizure medications (anti-convulsants) are also used either alone or in combination to treat individuals with alternating hemiplegia of childhood who also have epilepsy and to prevent non-epileptic symptoms such as hemiplegia and dystonia. The effectiveness of these medications is highly variable and they are often minimally effective or ineffective. Benzodiazepines such as diazepam have been used to reduce the duration of dystonic episodes.

Because some hemiplegic episodes have an early phase where individuals feel unwell, some researchers have recommended using certain medications to prematurely induce sleep. This can lessen the duration and severity of an episode. Such medications include buccal midazolam, chloral hydrate, melatonin, niaprazine or rectal diazepam.

Severe episodes of alternating hemiplegia of childhood can require hospitalization. In some cases, epileptic seizures can necessitate urgent medical intervention including intravenous to halt seizures or induce sleep in the setting of severe prolonged dystonia.

The various symptoms of alternating hemiplegia of childhood can affect a child’s growth and development. Episodes can disrupt daily life and impact a child’s ability to learn and participate in various activities. Proactive management of potential complications is required. A supportive team approach for children with alternating hemiplegia of childhood is of benefit and may include special education, physical therapy, and additional social, medical or vocational services. Genetic counseling may be of benefit for affected individuals and their families.

Investigational therapies

Well designed clinical trials have proved challenging to perform in alternating hemiplegia of childhood due to both the rarity of the disorder and the difficulty in clearly showing long-term improvement. Flunarizine has been the most well studied, but published reports include a relatively small number of patients. However, because there are currently no approved treatments proven to improve symptoms in alternating hemiplegia of childhood, many individuals undergo treatment trials with the supervision of their physician to try to determine whether a given medication might be helpful in reducing the frequency and/or severity of either the episodes of weakness or seizure like episodes. A few reports have indicated that a drug called topiramate, usually used to treat epilepsy, might improve the frequency and severity of both non-epileptic paroxysmal symptoms, as well as seizure-like episodes, in individuals with alternating hemiplegia of childhood. More research is necessary to determine the long-term safety and true effectiveness of flunarizine, topiramate and other investigational therapies such as sodium oxybate in the treatment of individuals with alternating hemiplegia of childhood.

Alternating hemiplegia of childhood prognosis

Although the disorder is named of “childhood” those affected by alternating hemiplegia of childhood do not grow out of the disorder. Children with the benign form of alternating hemiplegia have a good prognosis. Those who experience the more severe form have a poor prognosis because intellectual and mental capacities do not respond to drug therapy, and balance and gait problems continue. Over time, walking unassisted becomes difficult or impossible.

The alternating hemiplegia of childhood episodes may change and sometimes even decrease in frequency as a child gets older.

Every child with alternating hemiplegia of childhood is unique, and children can be severely or mildly affected. However, as children get older, developmental problems between episodes became more apparent. These developmental problems may include difficulties in fine and gross motor function, cognitive function, speech and language and even social interactions. There is developing evidence that alternating hemiplegia of childhood may cause ongoing mental and neurological deficits with a progressive course. Early intervention for such children is extremely important to help maximize their developmental achievements.

Although there is no proof that alternating hemiplegia of childhood limits life expectancy, these children do appear more susceptible to complications such as aspiration, which can sometimes be life-threatening. In rare cases, children have died suddenly and unexpectedly, in circumstances similar to the sudden death reported in patients with epilepsy (known as SUDEP, or sudden unexplained death in epilepsy). For this reason, careful evaluation to identify problems which could be associated with such episodes is a critical part of the care plan for these patients. Monitoring oxygen levels and insuring safe management of secretions may be needed during severe episodes.

References