American dog tick

American dog tick also called Dermacentor variabilis or wood tick, the 8-legged adult tick is the primary vector for Rickettsia rickettsii, the bacterium causing Rocky Mountain spotted fever and can also cause canine tick paralysis in humans and domestic or companion animals 1. American dog tick also is reportedly capable of transmitting Coxiella burnetii (Q fever) and Francisella tularensis (tularemia) 2. Consequently, expansion of its geographic range poses a significant public health problem in areas previously free of this vector species 3. American dog tick or wood tick, is found predominantly in the United States, east of the Rocky Mountains and as its name suggests, is most commonly found on dogs as an adult. American dog tick also occurs in certain areas of Canada, Mexico and the Pacific Northwest of the U.S. 4. American dog tick is a 3-host tick, targeting smaller mammals as a larva and nymph and larger mammals as an adult. Although it is normally found on dogs, this tick will readily attack larger animals, such as cattle, horses, and even humans. While the American dog tick can be managed without pesticides, when necessary a recommended acaricide is an effective way of eliminating an existing tick infestation near residences.

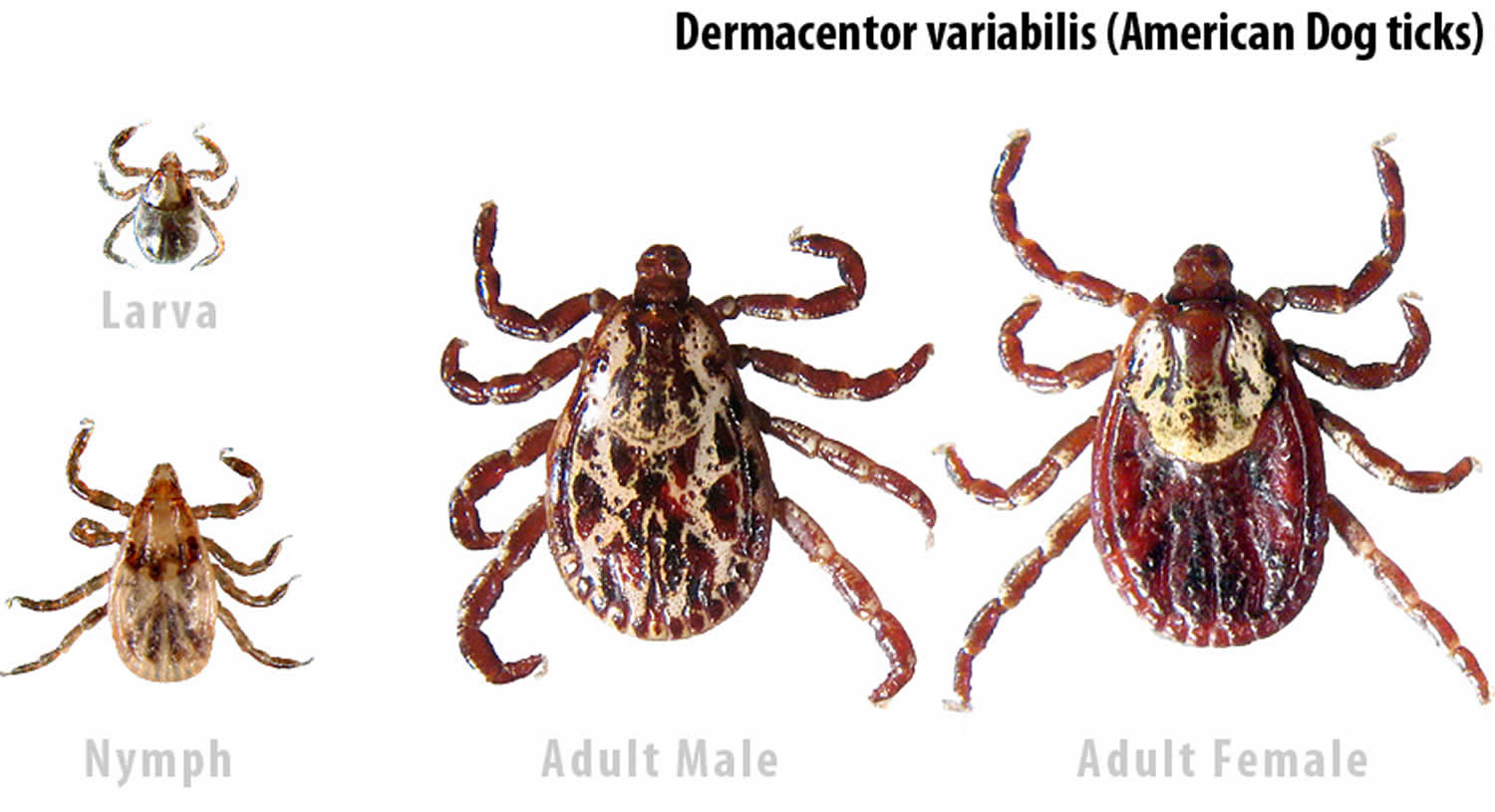

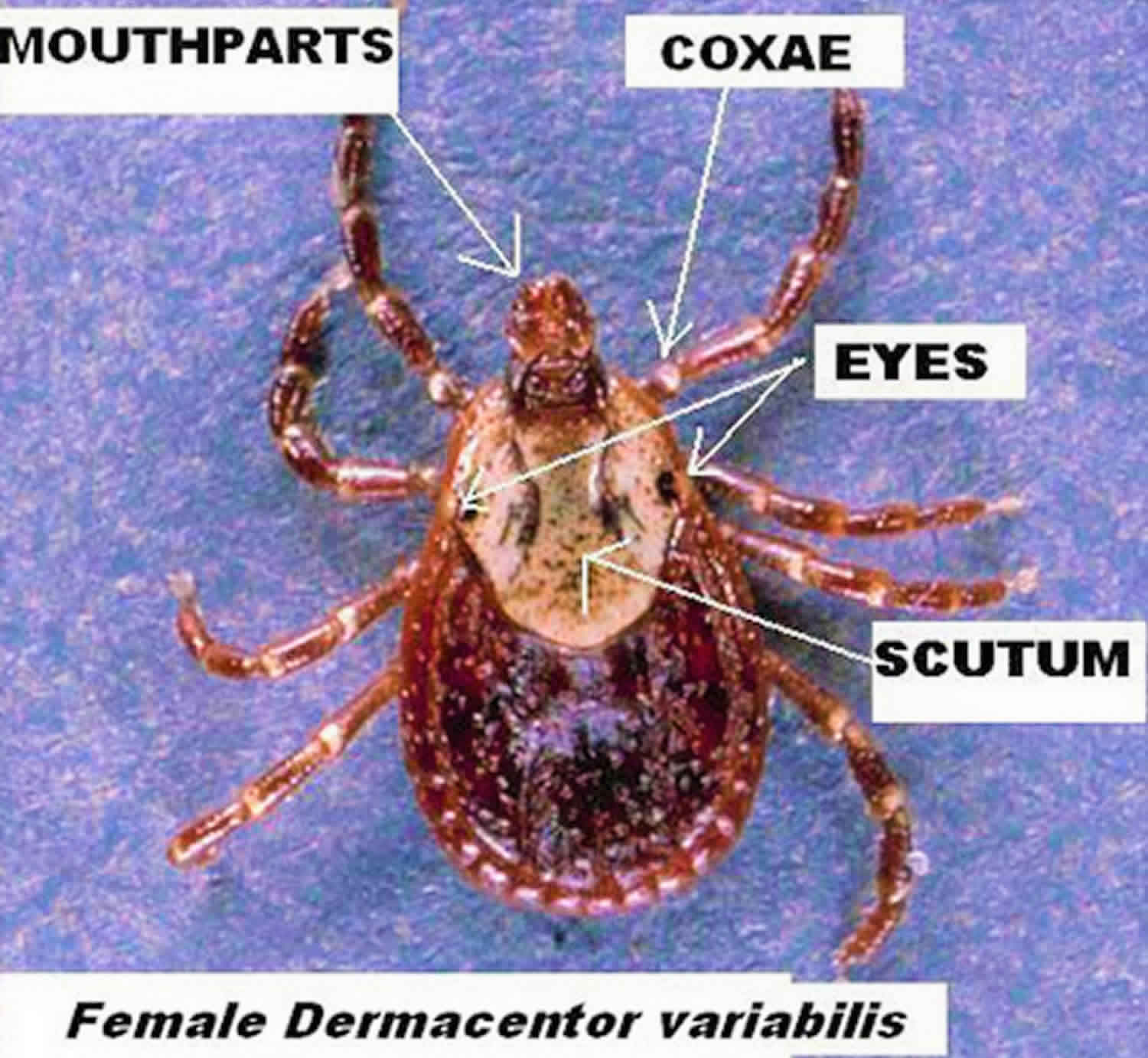

The 8-legged adult male and female American dog ticks are typically brown to reddish-brown in color with gray/silver markings on their scutum (dorsal “shield”). The female will vary in size depending on whether or not it has blood fed. Unfed females are typically 5 mm long and are slightly larger than males, which are about 3.6 mm long. Females can be distinguished by a short or small dorsal scutum, right behind the mouthparts while the male scutum covers the majority of its dorsal surface. Blood-fed (engorged) females can enlarge up to 15 mm long and 10 mm wide.

Figure 1. American dog ticks

Figure 2. Adult female American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis (Say)

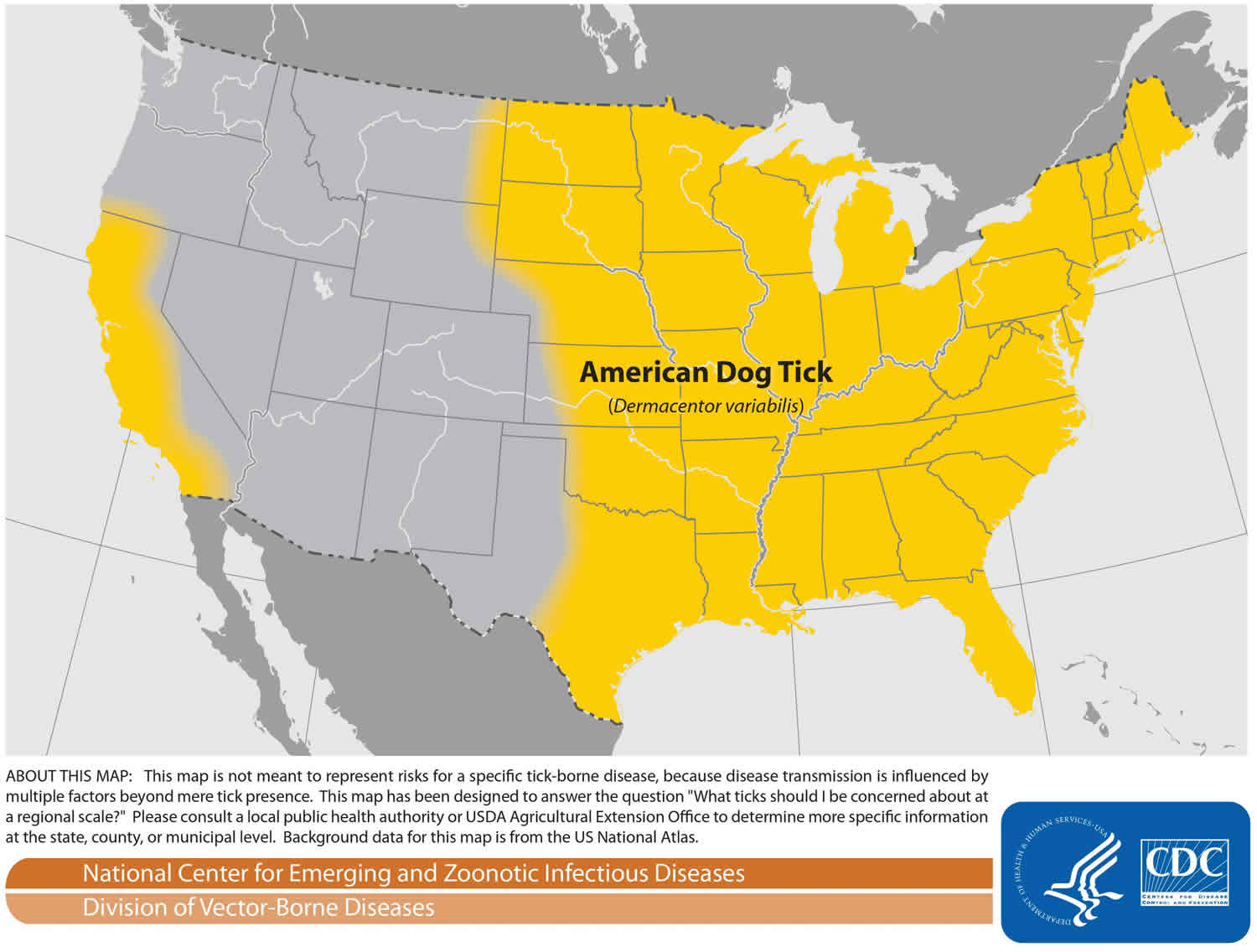

American dog tick distribution

The American dog tick is widely distributed in the United States east of a line drawn from Montana to South Texas. It is also found in Canada, east of Saskatchewan, and in California, west of the Cascade and the Sierra Nevada Mountain ranges. This species is most abundant in the eastern United States from Massachusetts south to Florida but is also common in more central areas of the U.S., including Iowa and Minnesota 5.

It was been suggested that adult ticks move to the edge of the roads and trails in an attempt to find a host, or “quest.” Some have hypothesized that because many animals typically follow trails, they leave an odor that attracts these ticks causing them to move toward and quest alongside trails in attempts to find a host 4.

Figure 4. American dog tick geographic distribution

American dog tick life cycle

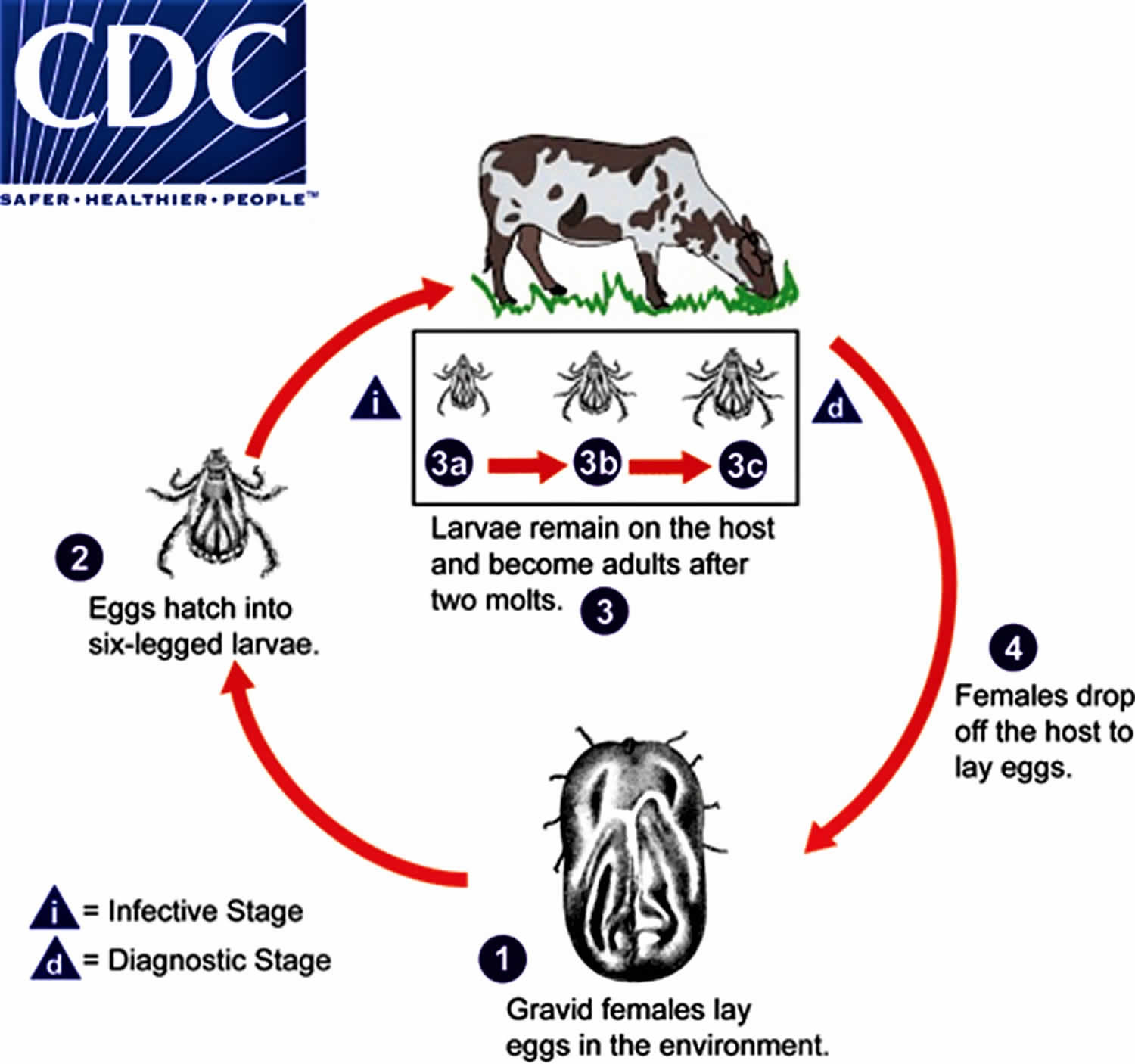

American dog tick develops from the egg stage, to the 6-legged larva, to the 8-legged nymph, and finally to the adult. The cycle requires a blood meal before progression from larva to nymph, from nymph to adult and by the adult for egg production. This cycle also requires three different hosts and requires at least 54 days to complete, but can take up to two years depending on the host availability, host location and the temperature.

After five to 14 days of blood feeding, a fully engorged female American dog tick drops from the host. She digests the blood meal and develops her egg clutch over the next four to 10 days. She then lays anywhere from 4,000 to 6,500 eggs on the ground 5. About 26 to 40 days later, depending on the temperature, the eggs hatch into larvae 6.

After hatching, larvae remain on the ground or climb growing vegetation where they wait for small mammals, such as mice, to serve as hosts for their first blood meal. This host location behavior is called questing. Under favorable conditions, larvae can survive up to 11 months without feeding. After contacting and attaching to a host, larvae require from two to 14 days to complete blood feeding. After feeding, larvae detach from their host and fall to the ground where they digest their blood meal and molt into the nymphal stage. This process can take as little as a week, although this period is often prolonged.

Nymphs can survive six months without a blood meal. After successfully questing for their second host, which is normally a slightly larger mammal (such as a raccoon or opossum), the nymphs will blood feed over a three to 10-day period. After engorging, they fall off the host, digest their blood meal and molt into an adult. This process can take anywhere from three weeks to several months.

Adults can survive two years without feeding, but readily feed on dogs or other larger animals when available. Questing adult ticks climb onto a grass blade or other low vegetation, cling to it with their third pair of legs, and wave its legs as a potential host approaches. As the hosts brush the vegetation, the ticks grab onto the passing animal. Mating occurs on the host and the female engorges within six to 13 days after which she drops from the host to lay her eggs and then she dies, thus completing the cycle 5.

Figure 5. American dog tick life cycle

Footnote: Life cycle of one-host American dog ticks. One-host American dog ticks remain on the same host for the larval, nymphal and adult stages, only leaving the host prior to laying eggs. Gravid females lay eggs in the environment (number 1). The eggs hatch into six-legged larvae (number 2). Larvae seek out and attach to the host and after two molts, develop into adults (number 3a & number 3b). Although humans may serve as incidental hosts for species normally found on other animals, they usually do not host all three stages. Females drop from the host to lay eggs (number 4) and the cycle repeats. The adult is considered the diagnostic stage, as identification to the species level is best achieved with adults.

Footnote: Life cycle of one-host American dog ticks. One-host American dog ticks remain on the same host for the larval, nymphal and adult stages, only leaving the host prior to laying eggs. Gravid females lay eggs in the environment (number 1). The eggs hatch into six-legged larvae (number 2). Larvae seek out and attach to the host and after two molts, develop into adults (number 3a & number 3b). Although humans may serve as incidental hosts for species normally found on other animals, they usually do not host all three stages. Females drop from the host to lay eggs (number 4) and the cycle repeats. The adult is considered the diagnostic stage, as identification to the species level is best achieved with adults.American dog tick seasonality

Adult American dog ticks overwinter in the soil and are most active from around mid-April to early September. Larvae are active from about March through July and nymphs are usually found from June to early September 7. In northern areas, such as Massachusetts and Nova Scotia, adults appear from April to August with a peak in May and June 8. In central latitudes of the U.S., such as Virginia, adults are found to be active from April to September/October with peaks in May and July 9. In Ohio, adult activity occurred between April and September with a peak in May/June and a second smaller peak in August/September 10.

A study done in Lexington, Kentucky, found the duration of American dog tick’s spring activity was related to its overwintering success. This study also concluded that overwintering adult American dog ticks remained active throughout the entire season 11. This same study reported that adult activity began a week or two earlier than in more northern states, such as Ohio, and a week or two later than in more southern states, such as Georgia. In Georgia, adult ticks are active from late March to August with peaks from early May to late June 12. While in Florida, adult American dog tick activity occurs from April to July 13.

American dog tick diseases

The American dog tick is the primary vector for Rickettsia rickettsii, the bacterium causing Rocky Mountain spotted fever, although it is also known to transmit the causative agent of tularemia and can cause canine tick paralysis. First discovered in the late 19th century in the Rocky Mountain region, Rocky Mountain spotted fever is more commonly reported in eastern U.S. Rickettsia rickettsii, the causative agent of Rocky Mountain spotted fever, is primarily vectored by American dog tick to dogs and humans following its acquisition from rodents. Overwintering larvae can also acquire Rocky Mountain spotted fever transovarially (mother to egg) yielding Rocky Mountain spotted fever-infected larvae 14. Because larval and nymphal ticks rarely bite humans, the adult tick is the primary lifestage of concern for humans. In the southeast U.S., peak occurrence of the disease is in July, at or shortly after the peak activity of adult American dog tick.

Rocky Mountain spotted fever is an infectious disease. The rickettsia affect small peripheral blood vessels causing rashes to develop within two to five days after fever begins. These rashes are known to start in the wrists and ankles and move up to the rest of the body. The look of the rash can vary widely over the course of illness. Some rashes can look like red splotches and some look like pinpoint dots. While almost all patients with Rocky Mountain spotted fever will develop a rash, it often does not appear early in illness, which can make Rocky Mountain spotted fever difficult to diagnose. Because of its direct association with adult American dog tick, Rocky Mountain spotted fever is a seasonal disease, and is more prevalent during the months between April and September. Symptoms usually appear within two to 14 days, with averages of around a week. Fever, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headaches, muscle pain and lack or appetite are all symptoms of this disease. Clinical symptoms include elevated liver enzymes, abnormal platelet count, and electrolyte abnormalities 15. Mortality from this disease in humans is 20 to 25% if untreated and 5% with appropriate clinical therapy. In order for transmission to occur, however, the tick must be attached for six to eight hours and in some cases transmission requires more than 24 hours 16.

Early signs and symptoms are not specific to Rocky Mountain spotted fever (including fever and headache). However, the disease can rapidly progress to a serious and life-threatening illness. See your healthcare provider if you become ill after having been bitten by a tick or having been in the woods or in areas with high brush where ticks commonly live. Some patients who recover from severe Rocky Mountain spotted fever may be left with permanent damage, including amputation of arms, legs, fingers, or toes (from damage to blood vessels in these areas); hearing loss; paralysis; or mental disability. Any permanent damage is caused by the acute illness and does not result from a chronic infection.

Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever signs and symptoms can include:

- Fever

- Headache

- Rash

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Stomach pain

- Muscle pain

- Lack of appetite

American dog tick can also vector Francisella tularensis, the organism causing tularemia. This gram negative coccobacillus (bacteria) also can be transmitted by contact with arthropods including other ticks, deer flies, mosquitoes, fleas, as well as from infected animals (principally rabbits) to hunters and ranchers. However person-to-person contact is rare. Incubation for this disease is usually three to five days but can take up to 21 days for symptoms to appear 17. Symptoms of tularemia include chills, fever, prostration, ulceration at the site of the bite, and tender, swollen lymph nodes. If untreated, fatality rate may be as high as 5 to 7%. Tularemia occurs only in the northern hemisphere and most frequently in Scandinavia, North America, Japan, and Russia 18.

Canine tick paralysis can occur due to the feeding of American dog tick. In this case, the tick will attach to the back of the dog’s neck, or at the base of the skull, and feed for at least five to six days. It is believed to release a salivary gland protein into the body. Paralytic symptoms then become visible through unsteadiness and loss of reflex actions. If the tick is not removed, respiratory failures can be fatal. Such paralysis is not limited to dogs, as it can happen to children as well. Once the tick is properly removed, recovery is usually within one to three days 19. In the U.S., the fatality rate is about 10% in the Pacific Northwest, and most of those who die are children 20.

How to remove a tick

If you find a tick attached to your skin, there’s no need to panic—the key is to remove the tick as soon as possible. There are several tick removal devices on the market, but a plain set of fine-tipped tweezers work very well.

To remove a tick, follow these steps:

- Using a pair of fine-tipped or pointy tweezers, grasp the tick by the head or mouth-parts right where they enter the skin. DO NOT grasp the tick by the body.

- Without jerking, pull firmly and steadily directly outward. DO NOT twist the tick out or apply petroleum jelly, a hot match, alcohol, nail polish or any other irritant to the tick in an attempt to get it to back out. Your goal is to remove the tick as quickly as possible–not waiting for it to detach. If the mouth-parts to break off and remain in the skin, remove the mouth-parts with tweezers. If you are unable to remove the mouth easily with clean tweezers, leave it alone and let the skin heal.

- Never crush a tick with your fingers. Dispose of a live tick by putting it in alcohol, placing it in a sealed bag/container, wrapping it tightly in tape, or flushing it down the toilet.

- Clean the bite wound with with rubbing alcohol or soap and water. Keep in mind that certain types of fine-pointed tweezers, especially those that are etched, or rasped, at the tips, may not be effective in removing nymphal deer ticks. Choose unrasped fine-pointed tweezers whose tips align tightly when pressed firmly together.

Then, monitor the site of the bite for the appearance of a rash beginning 3 to 30 days after the bite. At the same time, learn about the other early symptoms of Lyme disease and watch to see if they appear in about the same timeframe. If a rash or other early symptoms develop, see a physician immediately. Be sure to tell the doctor about your recent tick bite, when the bite occurred, and where you most likely acquired the tick.

American dog tick diseases prevention

Prevention is the best way to avoid tick-borne illness. Except for tick-borne encephalitis, there is no vaccine available to prevent tick-borne disease. Protective clothing, such as long pants, long sleeves, and closed shoes should be worn in tick-infested areas, particularly in the late spring in summer when most cases occur. Pant legs should be tucked into socks when walking through high grass and brush. Permethrin, which is an insecticide, may be applied to clothing and is quite effective in repelling ticks. Other tick repellents such as diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET) may be applied to skin or clothing, with variable effectiveness. DEET can be quite toxic, with effects ranging from local skin irritation to seizures. DEET should be avoided in infants.

Use insect repellents and protective clothing when in tick-infested areas. Tuck pant legs into socks. Carefully check the skin and hair after being outside and remove any ticks you find.

If you find a tick on your child, write the information down and keep it for several months. Many tick-borne diseases do not show symptoms right away, and you may forget the incident by the time your child becomes sick with a tick-borne disease.

Before you go outdoors

- Know where to expect ticks. Ticks live in grassy, brushy, or wooded areas, or even on animals. Spending time outside walking your dog, camping, gardening, or hunting could bring you in close contact with ticks. Many people get ticks in their own yard or neighborhood.

- Treat clothing and gear with products containing 0.5% permethrin. Permethrin can be used to treat boots, clothing and camping gear and remain protective through several washings. Alternatively, you can buy permethrin-treated clothing and gear.

- Use Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)-registered insect repellents containing DEET, picaridin, IR3535, Oil of Lemon Eucalyptus (OLE), para-menthane-diol (PMD), or 2-undecanone (https://www.epa.gov/insect-repellents). EPA’s helpful search tool (https://www.epa.gov/insect-repellents/find-repellent-right-you) can help you find the product that best suits your needs. Always follow product instructions.

- DO NOT use insect repellent on babies younger than 2 months old.

- DO NOT use products containing OLE or PMD on children under 3 years old.

Avoid contact with ticks

- Avoid wooded and brushy areas with high grass and leaf litter.

- Walk in the center of trails.

After you come indoors

Check your clothing for ticks. Ticks may be carried into the house on clothing. Any ticks that are found should be removed. Tumble dry clothes in a dryer on high heat for 10 minutes to kill ticks on dry clothing after you come indoors. If the clothes are damp, additional time may be needed. If the clothes require washing first, hot water is recommended. Cold and medium temperature water will not kill ticks.

Examine gear and pets. Ticks can ride into the home on clothing and pets, then attach to a person later, so carefully examine pets, coats, and daypacks.

Shower soon after being outdoors. Showering within two hours of coming indoors has been shown to reduce your risk of getting Lyme disease and may be effective in reducing the risk of other tickborne diseases. Showering may help wash off unattached ticks and it is a good opportunity to do a tick check.

Check your body for ticks after being outdoors. Conduct a full body check upon return from potentially tick-infested areas, including your own backyard. Use a hand-held or full-length mirror to view all parts of your body. Check these parts of your body and your child’s body for ticks:

- Under the arms

- In and around the ears

- Inside belly button

- Back of the knees

- In and around the hair

- Between the legs

- Around the waist

Figure 7. Check your body for ticks

Preventing tick bites

Tick exposure can occur year-round, but ticks are most active during warmer months (April-September). Know which ticks are most common in your area (see geographic distribution of ticks that bite humans below).

When spending time outdoors, make these easy precautions part of your routine:

- Wear enclosed shoes and light-colored clothing with a tight weave to spot ticks easily

- Scan clothes and any exposed skin frequently for ticks while outdoors

- Stay on cleared, well-traveled trails

- Use insect repellant containing DEET (Diethyl-meta-toluamide) on skin or clothes if you intend to go off-trail or into overgrown areas

- Avoid sitting directly on the ground or on stone walls (havens for ticks and their hosts)

- Keep long hair tied back, especially when gardening

- Do a final, full-body tick-check at the end of the day (also check children and pets)

When taking the above precautions, consider these important facts:

- If you tuck long pants into socks and shirts into pants, be aware that ticks that contact your clothes will climb upward in search of exposed skin. This means they may climb to hidden areas of the head and neck if not intercepted first; spot-check clothes frequently.

- Clothes can be sprayed with either DEET or Permethrin. Only DEET can be used on exposed skin, but never in high concentrations; follow the manufacturer’s directions.

- Upon returning home, clothes can be spun in the dryer for 20 minutes to kill any unseen ticks

- A shower and shampoo may help to remove crawling ticks, but will not remove attached ticks. Inspect yourself and your children carefully after a shower. Keep in mind that nymphal deer ticks are the size of poppy seeds; adult deer ticks are the size of apple seeds.

Any contact with vegetation, even playing in the yard, can result in exposure to ticks, so careful daily self-inspection is necessary whenever you engage in outdoor activities and the temperature exceeds 45° F (the temperature above which deer ticks are active). Frequent tick checks should be followed by a systematic, whole-body examination each night before going to bed. Performed consistently, this ritual is perhaps the single most effective current method for prevention of Lyme disease.

Finally, prevention is not limited to personal precautions. Those who enjoy spending time in their yards can reduce the tick population around the home by:

- keeping lawns mowed and edges trimmed

- clearing brush, leaf litter and tall grass around houses and at the edges of gardens and open stone walls

- stacking woodpiles neatly in a dry location and preferably off the ground

- clearing all leaf litter (including the remains of perennials) out of the garden in the fall

- having a licensed professional spray the residential environment (only the areas frequented by humans) with an insecticide in late May (to control nymphs) and optionally in September (to control adults).

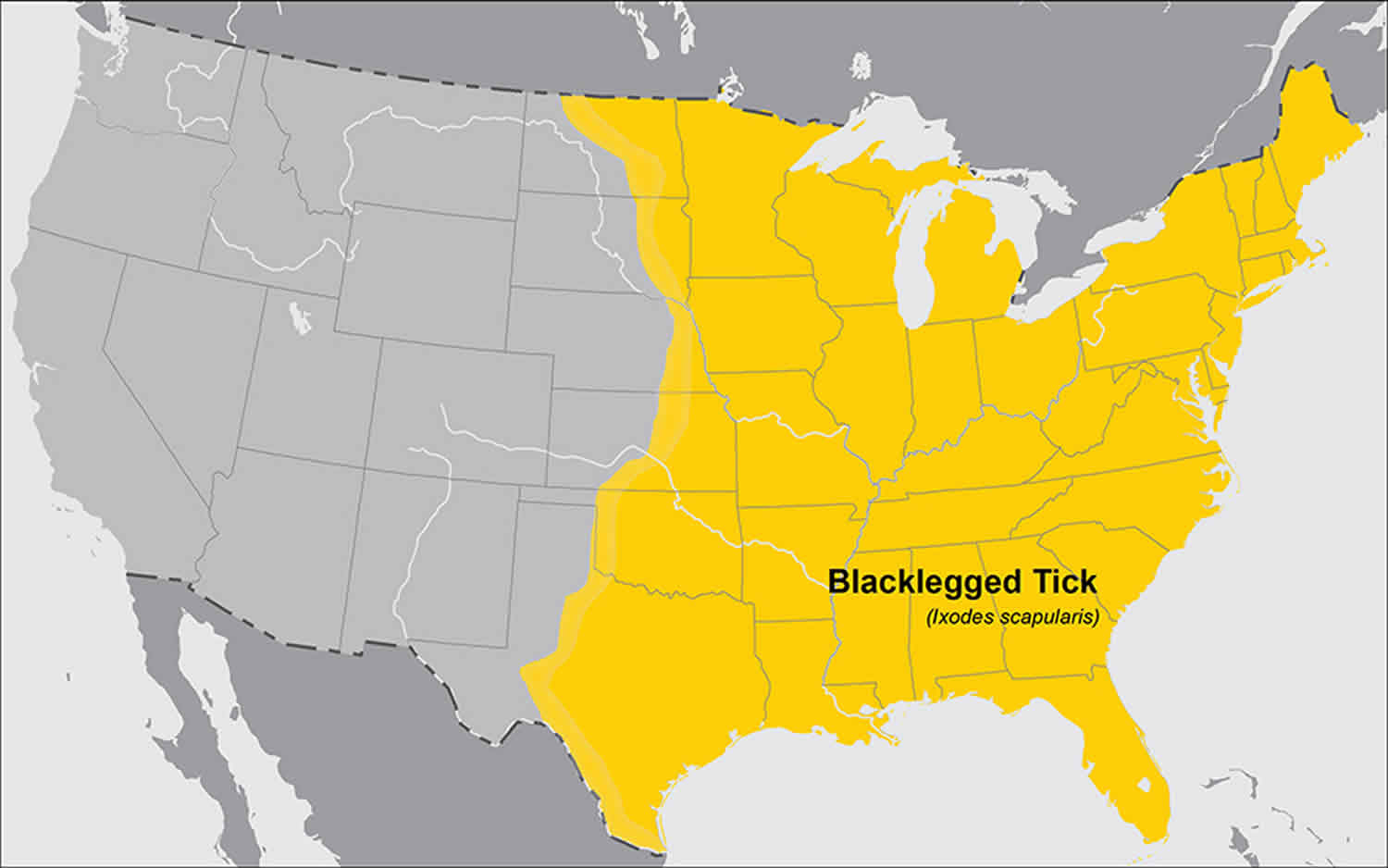

American dog tick vs Deer tick

Deer tick is also called blacklegged tick or Ixodes scapularis, is an important vector of the Lyme disease spirochetes, Borrelia burgdorferi and Borrelia mayonii, as well as the agents of human babesiosis, Babesia microti, and human granulocytic ehrlichiosis 21. Deer tick also transmits Anaplasma phagocytophilum (anaplasmosis), Borrelia miyamotoi disease (a form of relapsing fever), Ehrlichia muris eauclairensis (ehrlichiosis) and Powassan virus (Powassan virus disease). A significant feature in the transmission dynamics of Borrelia burgdorferi is the importance of the nymphal stage’s activity preceding that of the larvae which allows for an efficient transmission cycle 22. Before and during larval tick feeding, the naturally infected nymphs transmit Borrelia burgdorferi to reservoir hosts. The newly hatched spirochete-free larvae 23 acquire the bacteria from the reservoir host and retain infection through the molting process. In the springtime, nymphs derived from infected larvae transmit infection to susceptible animals, which will serve as hosts for larvae later in the summer 24. The greatest risk of being bitten exists in the spring, summer, and fall in the Northeast, Upper Midwest and mid-Atlantic. However, adult ticks may be out searching for a host any time winter temperatures are above freezing. All life stages bite humans, but nymphs and adult females are most commonly found on people.

Figure 8. Deer ticks

Figure 9. Geographic distribution of deer ticks (blacklegged ticks) that bite humans

References- Sonenshine DE. Range Expansion of Tick Disease Vectors in North America: Implications for Spread of Tick-Borne Disease. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(3):478. Published 2018 Mar 9. doi:10.3390/ijerph15030478 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5877023

- Wood H., Dillon L., Patel S.N., Ralevski F. Prevalence of rickettsia species on Dermacentor variabilis from Ontario, Canada. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2016;7:1044–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2016.06.001

- James A.M., Burdett C., McCool M.J., Fox A., Riggs P. The geographic distribution and ecological preferences of the American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis (Say), in the USA. Med. Vet. Entomol. 2015;29:178–188. doi: 10.1111/mve.12099

- Mcnemee RB, Sames WJ, Maloney Jr FA. 2003. Occurrence of Dermacentor variabilis (Acari:Ixodidae) around a porcupine (Rodentia: Erthethizontidae) carcass at Camp Ripley, Minnesota. Journal of Medical Entomology 40: 108-111.

- Matheson R. 1950. Medical Entomology, 2nd Edition. Comstock Publishing Company, Inc. Ithaca, NY.

- James M, Robert FH. 1969. Herm’s Medical Entomology. 6th Edition. pp. 326-329. The Macmillan Company. Toronto, Ontario.

- Goddard J. 1996. Physician’s Guide to Arthropods of Medical Importance. pp. 287-302. CRC Press. Jackson, Mississippi.

- Campbel A. 1979. Ecology of the American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis in southwestern Nova Scotia. Recent Advances in Acarology. Rodriguez JG (editor). Volume 2: 135-143.

- Carroll JF, Nichols JD. 1986. Parasitization of meadow voles, Microtus pennsylvanicus (Ord), by American dog ticks, Dermacentor variabilis (Say), and adult tick movement during high host density. Journal of Entomological Science 21: 102-113.

- Conlon JM, Rockett CL. 1982. Ecological investigations of the American dog tick, Dermacentor variabilis (Say), in northwest Ohio (Acari: Ixodidae). International Journal of Acarology 8: 125-131.

- Burg JG. 2001. Seasonal Activity and spatial distribution of host-seeking adults of the tick Dermacentor variabilis. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 15: 413-421.

- Newhouse VF. (1983) Variations in population density, movement, and rickettsial infection rates in a local population of Dermacentor variabilis (Acarina: Ixodidae) ticks in the piedmont of Georgia. Environmental Entomology 12: 1737-1746.

- McEnroe, W.D. 1979b. The effect of the temperature regime on Dermacentor variabilis (Say) populations in eastern North America. Acarologia 20: 58-67.

- Piesman J, Gage KL. 1996. Ticks and mites and the agents they transmit. The Biology of Disease Vectors. Beaty BJ, Marquardt WC (editors). pp. 160-174. University Press of Colorado. Newot, CO.

- Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (RMSF). https://www.cdc.gov/rmsf

- Thorner AR, Walker D, Petri WA. 1998. Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. Clinical Infectious Diseases by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 27: 1353-1360.

- Tularemia. https://www.cdc.gov/tularemia

- Eddis J, Oyston CF, Green M, Titball RW. 2002. Tularemia. Clinical Microbiology Reviews: 15: 631-646.

- Schmitt N. Bowner EJ, Gregson JD. 1969. Tick paralysis in British Columbia. Canadian Medical Association 100: 417-21.

- Gregson JD. 1973. Tick paralysis: an appraisal of natural and experimental data. Monograph No. 9. Canada Department of Agriculture, Ottawa.

- Des Vignes F, Fish D. 1997. Transmission of the agent of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis by host-seeking Ixodes scapularis (Acari: Ixodidae) in southern New York State. Journal of Medical Entomology 34: 379-382.

- Spielman A, Wilson ML, Levine JE, Piesman J. 1985. Ecology of Ixodes dammini-borne human babesiosis and Lyme disease. Annual Review of Entomology 30: 439-460.

- Piesman J, Donahue JG, Mather TN, Spielman A. 1986a. Transovarially acquired Lyme disease spirochetes (Borrelia burgdorferi) in field-collected larval Ixodes dammini (Acari: Ixodidae). Journal of Medical Entomology. 23: 219.

- Fish D. 1993. Population ecology of Ixodes dammini, pp. 25-42. In Ginsberg H [ed.], Ecology and environmental management of Lyme disease. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ.