Antisynthetase syndrome

Antisynthetase syndrome is a chronic autoimmune condition that affects the muscles and various other parts of the body 1. Antisynthetase syndrome is 2–3 times more common in women than in men 2. Antisynthetase syndrome signs and symptoms can vary but may include muscle inflammation (myositis), non-erosive arthritis, polyarthritis (inflammation of many joints), interstitial lung disease, unexplained fever and/or thickening and cracking of the hands (mechanic’s hands) and Raynaud phenomenon 3. The interstitial lung disease in antisynthetase syndrome patients is often severe and rapidly progressive, causing much of the increased morbidity and mortality associated with anti-synthetase syndrome as compared to the other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies 4.

The exact underlying cause of antisynthetase syndrome is unknown; however, the production of autoantibodies (antibodies that attack normal cells) that attack certain enzymes in the body called ‘aminoacyl-transfer RNA (tRNA) synthetases’ appears to be linked to the cause of the antisynthetase syndrome 5. Aminoacyl-transfer RNA (tRNA) synthetases are cellular enzymes involved in protein synthesis. Antisynthetase antibodies include Jo-1, PL-7, PL-12, OJ, EJ, KS, Wa, YRS and Zo. Anti-Jo-1 antibodies are the most commonly detected in antisynthetase syndrome. These autoantibodies may arise after viral infections, or patients may have a genetic predisposition.

Antisynthetase syndrome treatment is based on the signs and symptoms present in each person but may include corticosteroids, immunosuppressive medications, and/or physical therapy 6. Patients with antisynthetase syndrome may have corticosteroid-resistant myositis or interstitial lung disease, frequently requiring additional immunosuppressive medications 1.

Antisynthetase syndrome key points

- Antisynthetase syndrome can present with a wide variety of clinical manifestations, including myositis and interstitial lung disease. The type and severity of interstitial lung disease usually determine the long-term outcome.

- In the appropriate clinical setting, the diagnosis is usually confirmed by the detection of antibodies to various aminoacyl-transfer RNA synthetases, anti-Jo-1 antibody being the most common.

- Although glucocorticoids are considered the mainstay of treatment, additional immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine or methotrexate are often required as steroid-sparing agents and also to achieve disease control.In the case of severe pulmonary involvement, cyclophosphamide is recommended.

Antisynthetase syndrome cause

The underlying cause of antisynthetase syndrome is currently unknown. However, it is considered a chronic autoimmune disease. Autoimmune disorders occur when the body’s immune system attacks and destroys healthy body tissue by mistake. In antisynthetase syndrome, specifically, the production of autoantibodies (antibodies that attack normal cells instead of disease-causing agents) that recognize and attack certain enzymes in the body called ‘aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases’ appears to be linked to the cause of the syndrome. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases are involved in protein production within the body. These autoantibodies seem to appear after certain viral infections, drug exposure or in some people who already have a genetic predisposition. The exact role of autoantibodies in causing antisynthetase syndrome is not yet understood 7.

Aminoacyl-tRNA synthase autoantibodies associated with antisynthetase syndrome include anti-Jo1 (anti-histidyl), anti-EJ (anti-glycyl), anti-OJ (anti-isoleucyl), anti-PL7 (anti-threonyl), anti-PL12 (anti-alanyl), anti-SC (anti-lysil), anti-KS (anti-asparaginyl), anti-JS (anti-glutaminyl), anti-Ha or anti-YRS (anti-threonyl), anti-tryptophanyl, and anti-Zo (anti-phenylalanyl) autoantibodies, with anti-Jo1 being the most common 8. The exact role these autoantibodies play in the development of antisynthetase syndrome is not fully understood.

Some autoantibodies are more likely to be associated with specific symptoms. Muscle disease occurs more often with anti-Jo1 or anti-PL7. Interstitial lung disease occurs more often with anti-PL7, anti-PL12, anti-KS, and anti-OJ autoantibodies. Some individuals with anti-OJ autoantibodies have developed severe muscle weakness.

These autoantibodies are believed to be produced after a ‘triggering’ event such as a viral infection or exposure to certain drugs. When the immune system responds to these triggering events, something goes wrong, and these autoantibodies are created that then damage healthy tissue.

Some affected individuals may have a genetic predisposition to developing antisynthetase syndrome. A genetic predisposition means that a person may carry a gene or genes for a particular condition, but the condition will not develop unless other factors help to trigger the disease. Most likely, antisynthetase syndrome is a multifactorial disease, in which multiple factors including immune, genetic and environmental ones are necessary for the development of the disorder.

Antisynthetase syndrome symptoms

The signs and symptoms of antisynthetase syndrome can present with a variety of clinical features and these may vary over time, but may include 9:

- Fever:

- Present in about 20% of patients

- May occur at onset of disease

- May persist or recur with relapses

- Loss of appetite

- Weight loss

- Muscle inflammation (myositis)

- Present in >90% of patients

- Associated with anti Jo-1 antibodies

- Proximal muscle weakness causes difficulty getting up from a chair or climbing stairs

- Muscles may be painful

- Weakness of the muscles involved in swallowing can result in aspiration pneumonia.

- Weakness of the muscles of respiration can result in shortness of breath

- Inflammation of multiple joints (polyarthritis)

- 50% of patients experience joint pains or arthritis

- Most often symmetrical arthritis of small joints of hands and feet

- Typically, does not result in bony erosions

- Interstitial lung disease (non-specific inflammation of the lungs) causing shortness of breath, coughing, and/or dysphagia

- Interstitial lung disease develops in most patients with anti- Jo-1 antisynthetase syndrome

- Often presents with sudden or gradual onset of shortness of breath on exertion

- Sometimes causes intractable dry cough

- May lead to pulmonary hypertension (increased pressure in pulmonary arteries) in patients with or without concomitant interstitial lung disease.

- Mechanic’s hands (thickened skin of tips and margins of the fingers)

- Affects about 30% of patients

- Thickened skin of tips and margins of the fingers

- Resembles a mechanic’s hands

- Raynaud phenomenon

- Occurs in about 40% of patients

- An episodic reduction in blood supply of fingers or toes which turn white, then blue and finally red

- A response to cold or emotional stress

- Some patients have associated nail fold capillary abnormalities

Some studies suggest that affected people may be at an increased risk for various types of cancer, occurring within 6–12 months of the diagnosis of antisynthetase syndrome 2. Age-appropriate screening is therefore recommended, as for dermatomyositis. Some symptoms of the disease seem to vary according to the autoantibody involved in the disease. Myopathy occurs more often in patients with anti-Jo-1 or anti-PL-7; anti-Jo-1 is related to severe arthritis and “mechanic’s hand”, while anti-PL-12 with higher rates of Raynaud phenomenon; and anti-PL-7, anti-PL-12, anti-KS, and anti-OJ with cases of interstitial lung disease 10.

Antisynthetase syndrome diagnosis

A diagnosis of antisynthetase syndrome is often suspected based on the presence of characteristic signs and symptoms once other conditions that cause similar features have been ruled out. Additional testing can then be ordered to confirm the diagnosis, determine the severity of the condition, and assist with determining treatment. This testing varies based on the signs and symptoms present in each person, but may include 5:

- Blood tests to evaluate levels of muscle enzymes such as creatine kinase (CK) and aldolase

- Laboratory tests to look for the presence of autoantibodies associated with antisynthetase syndrome

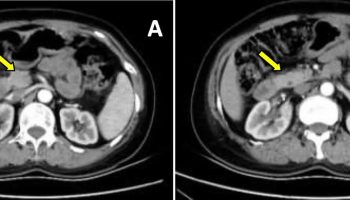

- High resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the lungs

- Electromyography (EMG)

- Muscle biopsy

- Pulmonary function testing

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of affected muscles

- Evaluation of swallowing difficulties and aspiration risk

- Lung biopsy

Not all patients with antisynthetase antibodies or even those classified as having the antisynthetase syndrome have all manifestations of this syndrome. Diagnosis is considered in patients with an antisynthetase antibody plus two major criteria or one major criterion and two minor criteria 10:

Major criteria:

- Interstitial lung disease (not explained by environmental, occupational, medication exposure, and not related to any other base disease)

- Polymyositis or dermatomyositis

Minor criteria:

- Arthritis

- Raynaud phenomenon

- Mechanic’s hand

Antisynthetase syndrome treatment

Corticosteroids are typically the first-line of treatment and may be required for several months or years. These medications are often given orally; however, in severe cases, intravenous methylprednisolone may be prescribe initially. Immunosuppressive medications may also be recommended, especially in people with severe muscle weakness or symptomatic interstitial lung disease 5. According to recent studies, Rituximab is the medication option when patients with lung disease do not respond well to other treatments 11.

Improvement in muscle strength can take several weeks or months. Symptomatic improvement is a more reliable indicator of response to treatment than serum creatine kinase (CK) levels.

Prophylactic treatment is recommended against steroid-induced osteoporosis and certain fungus infections such as Pneumocystis jirovecii. Need for immunisations should be assessed prior to commencing therapy.

Other immunosuppressive medications may be used, such as:

- Azathioprine

- Methotrexate

- Cyclophosphamide

- Tacrolimus

- Ciclosporin

- Mycophenolate

- Rituximab

Physical therapy is often necessary to improve weakness, reduce further muscle wasting from disuse, and prevent muscle contractures 2.

Antisynthetase syndrome prognosis

The long-term outlook (prognosis) for people with antisynthetase syndrome varies based on the severity of the condition and the signs and symptoms present. Although the condition is considered chronic and often requires long-term treatment, those with muscle involvement as the only symptom are generally very responsive to treatment with corticosteroids and/or immunosuppressive medications. When the lungs are affected, the severity and type of lung condition generally determines the prognosis 5. For example, patients with a progressive course of interstitial lung disease generally have a worse prognosis than those with a nonprogressive course, because respiratory failure is the main cause of death. However, in most cases the interstitial lung disease is nonprogressive 12.

Several studies have shown that the following factors may be associated with a worse prognosis 8:

- Older age at onset (greater than 60 years)

- Severity and extension of lung disease: The more severe and extensive lung involvement the worse the prognosis

- Presence of malignancy (cancer)

- Delay in diagnosis and treatment: Prognosis is better when the patients are treated early

- Having a negative Jo1 antibody test: Several studies have shown that Jo1 status seems to be associated with prognosis, suggesting that non-Jo1 patients (patients who have other anti-ARS antibodies, that are non-Jo1) have worse survival rates than Jo1 patients.

Antisynthetase syndrome life expectancy

Several studies suggest that patients with anti-PL7/PL12 autoantibodies have aggressive interstitial lung disease and decreased survival as compared to those with anti-Jo-1 autoantibodies 1. Additionally, patients with other anti-synthetase antibodies may not be appropriately diagnosed, which may slow the institution of therapy. One retrospective review found a 0.6 year median delay to diagnosis in patients with a non-Jo-1 anti-synthetase antibodies compared to patients with a Jo-1 antibody 13. In an analysis of patients with anti-synthetase syndrome, decreased survival was seen in patients without muscle weakness and with severe dyspnea 14. Patients with anti-PL7 or anti-PL12 often have severe and difficult to treat interstitial lung disease, frequently without myositis 15, suggesting that the pulmonary manifestations of anti-synthetase syndrome are responsible for the difference in mortality. These findings were reproduced in a 2014 meta-analysis of 27 studies on anti-synthetase syndrome, in which the authors found that arthralgia and interstitial lung disease predominate in anti-synthetase syndrome as compared to the other IIMs, and patients with Jo-1 have more myositis and a better prognosis compared to PL7 and PL12 16.

In a 2015 survival analysis of 45 patients with anti-synthetase syndrome-interstitial lung disease, 14% of patients had died at 5 years 17. Survivors more frequently had Jo-1 positivity and arthritis. Patients who died had a significantly lower baseline forced vital capacity (FVC) and more patients that could not perform diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO) due to severity of disease. A 2013 retrospective evaluation of 202 patients, with an anti-synthetase antibody from the University of Pittsburgh CTD Registry during a 24 year time period, found a 5-year cumulative survival of 90% for Jo-1 patients and 75% for non-Jo-1 patients 18. The 10-year survival was 70% for Jo-1 patients and 49% for non-Jo-1 patients. The most common causes of death were pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary hypertension. Of this cohort, 6% underwent lung transplantation. As patients with interstitial lung disease due to anti-synthetase syndrome often have severe and aggressive interstitial lung disease requiring multi-modality therapy, physicians should consider early referral to centers capable of lung transplantation when disease progresses or fails to adequately respond to treatment.

References- Witt LJ, Curran JJ, Strek ME. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Antisynthetase Syndrome. Clin Pulm Med. 2016;23(5):218–226. doi:10.1097/CPM.0000000000000171 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5006392

- Antisynthetase syndrome. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/antisynthetase-syndrome

- Connors GR, Christopher-Stine L, Oddis CV, Danoff SK. Interstitial lung disease associated with the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies: What progress has been made in the past 35 years? Chest. 2010;138:1464–1474.

- Kalluri M, Oddis CV. Pulmonary manifestations of the idiopathic inflammatory myopathies. Clinics in chest medicine. 2010;31:501–512.

- Antisynthetase syndrome: not just an inflammatory myopathy. Cleve Clin J Med. 2013 Oct;80(10):655-66. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.80a.12171. https://mdedge-files-live.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/files/s3fs-public/issues/articles/media_9d4816d_655.pdf

- Mirrakhimov AE. Antisynthetase syndrome: a review of etiopathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Curr Med Chem. 2015; 22(16):1963-75.

- Antisynthetase syndrome. Orphanet. https://www.orpha.net/consor/cgi-bin/Disease_Search.php?lng=EN&data_id=8611

- Rojas-Serrano J, Herrera-Bringas D, Mejía M, Rivero H, Mateos-Toledo H & Figueroa JE. Prognostic factors in a cohort of antisynthetase syndrome (ASS): serologic profile is associated with mortality in patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD).. Clin Rheumatol. September, 2015; 34(9):1563-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26219488

- Miller ML & Vleugels RA. Clinical manifestations of dermatomyositis and polymyositis in adults. UpToDate. 2016

- Esposito ACC, Gige TC & Miot HA. Syndrome in question: antisynthetase syndrome (anti-PL-7). An Bras Dermatol. 2016; 91(5):683-685. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5087238

- Sharp C, McCabe M, Dodds N, Edey A, Mayers L, Adamali H, Millar AB & Gunawardena H. Rituximab in autoimmune connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. Rheumatology (Oxford). April 8, 2016; pii: kew195. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27060110

- Trallero-Araguás E& cols. Clinical manifestations and long-term outcome of anti-Jo1 antisynthetase patients in a large cohort of Spanish patients from the GEAS-IIM group. Semin Arthritis Rheum. March 30, 2016; 16:30001-4.. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27139168

- Aggarwal R, Cassidy E, Fertig N, Koontz DC, Lucas M, Ascherman DP, Oddis CV. Patients with non-Jo-1 anti-tRNA-synthetase autoantibodies have worse survival than Jo-1 positive patients. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2013 annrheumdis-2012-201800

- Hervier B, Devilliers H, Stanciu R, Meyer A, Uzunhan Y, Masseau A, Dubucquoi S, Hatron P-Y, Musset L, Wallaert B. Hierarchical cluster and survival analyses of antisynthetase syndrome: phenotype and outcome are correlated with anti-tRNA synthetase antibody specificity. Autoimmunity reviews. 2012;12:210–217.

- Fischer A, Swigris JJ, du Bois RM, Lynch DA, Downey GP, Cosgrove GP, Frankel SK, Fernandez-Perez ER, Gillis JZ, Brown KK. Anti-synthetase syndrome in ANA and anti-Jo-1 negative patients presenting with idiopathic interstitial pneumonia. Respiratory medicine. 2009;103:1719–1724.

- Lega J-C, Fabien N, Reynaud Q, Durieu I, Durupt S, Dutertre M, Cordier J-F, Cottin V. The clinical phenotype associated with myositis-specific and associated autoantibodies: a meta-analysis revisiting the so-called antisynthetase syndrome. Autoimmunity reviews. 2014;13:883–891.

- Rojas-Serrano J, Herrera-Bringas D, Mejía M, Rivero H, Mateos-Toledo H, Figueroa J. Prognostic factors in a cohort of antisynthetase syndrome (ASS): serologic profile is associated with mortality in patients with interstitial lung disease (ILD) Clinical rheumatology. 2015;34:1563–1569.

- Aggarwal R, Cassidy E, Fertig N, Koontz DC, Lucas M, Ascherman DP, Oddis CV. Patients with non-Jo-1 anti-tRNA-synthetase autoantibodies have worse survival than Jo-1 positive patients. Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2013 annrheumdis-2012-201800.