What is alkaptonuria Alkaptonuria is a rare genetic metabolic disorder characterized by the accumulation of homogentisic acid in the body. Affected individuals lack enough functional

What is ambiguous genitalia Ambiguous genitalia encompasses a variety of disorders labeled as disorders of sex development or alternatively, differences in sex development ((Indyk JA.

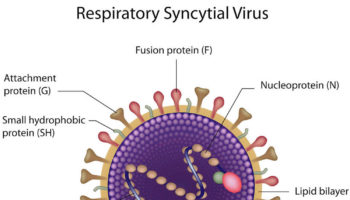

What is respiratory syncytial virus Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a common respiratory virus that infects your airways and lungs that usually causes mild, cold-like

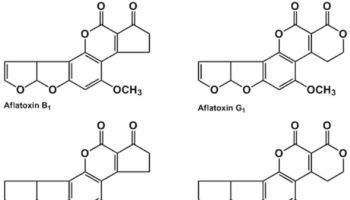

What is aflatoxin Aflatoxins are toxins produced by a Aspergillus flavus and and the closely related species Aspergillus parasiticus fungus, one of the most abundant soil-borne

What is SHBG SHBG is short for sex hormone binding globulin is also called Testosterone-Estradiol Binding Globulin, SHBG is a glycoprotein that is produced by

What does crystals in urine mean Crystals in urine is also called crystalluria, is a frequent finding in the routine examination of urine sediments. Your urine

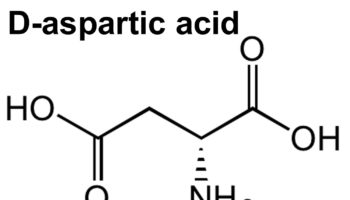

What does d aspartic acid do D-Aspartic acid is an non-essential amino acid that plays an important role in tuning testosterone production in the gonads

What is horse chestnut Horse chestnut is an herb prepared from the leaves or seeds of the horse chestnut tree (Aesculus hippocastanum L.), and is

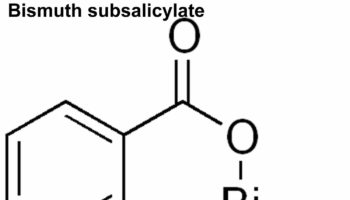

What is bismuth subsalicylate Bismuth subsalicylate is an antacid and anti-diarrhea medication that is used to treat diarrhea, heartburn, nausea, indigestion and upset stomach in adults

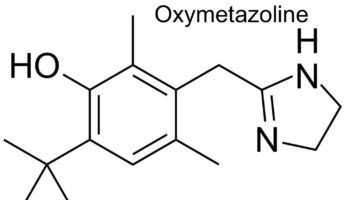

Oxymetazoline nasal spray Oxymetazoline is a a direct acting sympathomimetic vasoconstrictor that works by narrowing swollen blood vessels. Oxymetazoline works by narrowing the blood vessels in