What is biliary atresia?

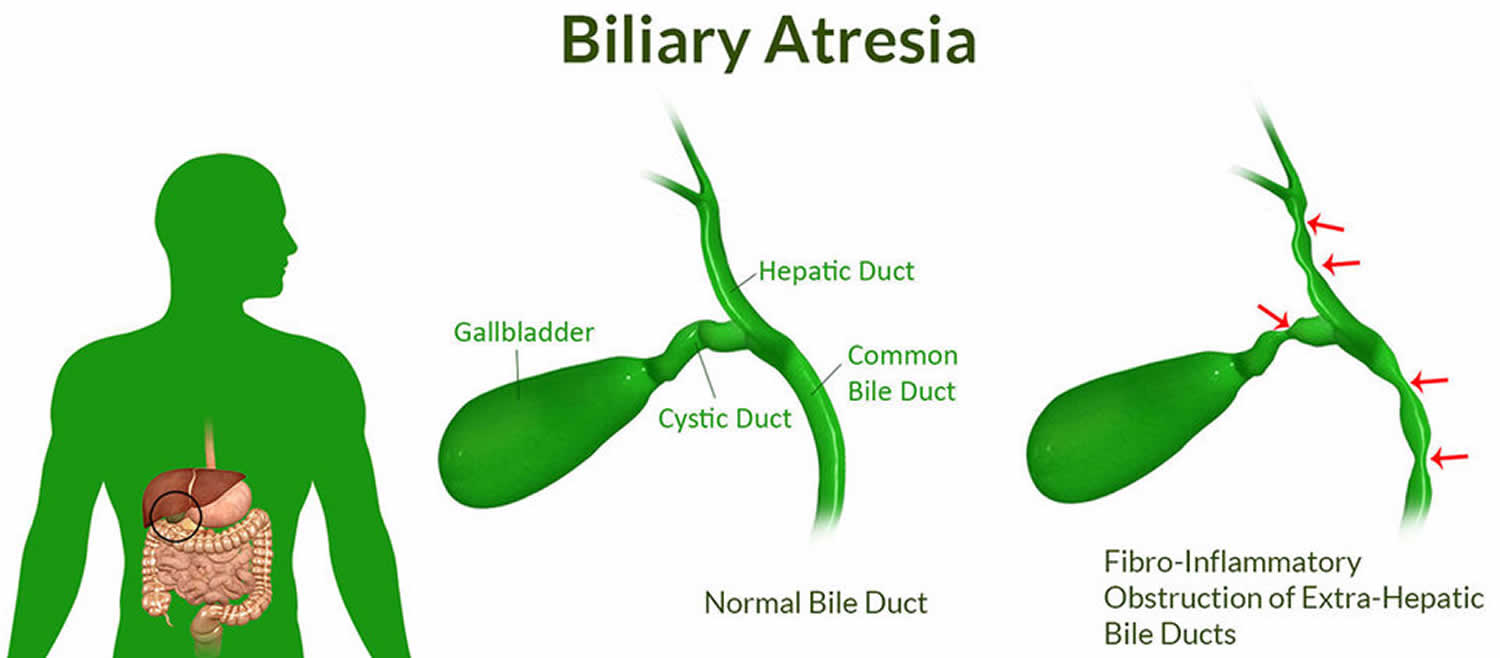

Biliary atresia is a condition in infants in which the bile ducts—tubes inside and outside the liver—are scarred and blocked. Bile ducts carry bile from the liver to the gallbladder for storage, and to the first part of the small intestine, also called the duodenum, for use in digestion. In infants with congenital biliary atresia, bile can’t flow into the intestine, so bile builds up in the liver and damages it. The damage leads to scarring, loss of liver tissue and function, and cirrhosis.

Biliary atresia is life-threatening, but with treatment, most infants with biliary atresia survive to adulthood.

Biliary atresia is rare and affects about 1 out of every 12,000 infants in the United States 1.

Biliary atresia only occurs in newborn infants. The disease is slightly more common in female infants and in infants with Asian or African American heritage 2.

Doctors treat biliary atresia with a surgery called the Kasai procedure and eventually, in most cases, a liver transplant. Thanks to advances in treatment, more than 80 to 90 percent of infants with biliary atresia survive to adulthood 3.

Figure 1. Biliary atresia

Types of biliary atresia

Doctors have identified different types of biliary atresia.

Biliary atresia without birth defects

In the most common type of biliary atresia, infants have no other major birth defects . Doctors may call this type perinatal biliary atresia or isolated biliary atresia 4. A recent North American study found that 84 percent of infants with biliary atresia have this type 5.

Biliary atresia with other congenital malformations

Some infants have major birth defects—including problems with the heart, spleen, or intestines—along with biliary atresia. Doctors may call this fetal or embryonic biliary atresia, also known as biliary atresia splenic malformation (BASM). A recent North American study found that 16 percent of infants with biliary atresia have major birth defects 6. Other birth defects include intestinal atresia, imperforate anus, kidney anomalies, and heart malformations, situs inversus, asplenia or polysplenia, malrotation and interrupted inferior vena cava 5. Data suggest that children with embryonic biliary atresia have poorer outcomes compared with those with perinatal biliary atresia, possibly due to the associated cardiac abnormalities 7.

What causes biliary atresia?

Experts don’t know what causes biliary atresia. Research suggests that infants develop biliary atresia in the womb or shortly after birth. Experts are trying to find out if one or more of the following factors could play a role in causing biliary atresia:

- infections with certain viruses

- coming into contact with harmful chemicals

- problems with the immune system

- a problem during liver and bile duct development in the womb

- certain genes or changes in genes—called mutations—that may increase the chances of developing biliary atresia

Biliary atresia is not an inherited disease, meaning it does not pass from parent to child.

Biliary atresia symptoms

Typically, the first sign of biliary atresia is yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes, called jaundice, which results from the buildup of bile in the body. Bile contains a reddish-yellow substance called bilirubin.

Infants often have jaundice in the first 2 weeks of life, so it is not easy to identify biliary atresia in newborn infants. Jaundice that lasts beyond 3 weeks of age may be the first sign of biliary atresia. Infants with biliary atresia typically develop jaundice by 3 to 6 weeks of age.

Infants with biliary atresia may also have pale yellow, gray, or white poop (stools). Poop change color because bilirubin is not reaching the intestines and passing out of the body in the poop.

Biliary atresia complications

Complications of biliary atresia include failure to thrive and malnutrition, cirrhosis and related complications, and liver failure.

Without treatment, infants with biliary atresia would develop cirrhosis within 6 months and liver failure within 1 year 2. By age 2, untreated infants would need a liver transplant to survive 8.

Early treatment with a surgery called the Kasai procedure may slow or, in some cases, prevent the development of cirrhosis and liver failure. Even with treatment, about half of children with biliary atresia will need a liver transplant by age 2. Two-thirds will need a liver transplant sometime during childhood 2.

Malnutrition

Even after treatment with the Kasai procedure, children with biliary atresia may have reduced bile flow to the small intestine and liver damage, leading to malnutrition and related problems with growth, such as failure to thrive. Read more about how biliary atresia affects nutrition.

Cirrhosis is a condition in which the liver breaks down and is unable to work normally. Scar tissue replaces healthy liver tissue, partly blocking the flow of blood through the liver. In the early stages of cirrhosis, the liver continues to work. As cirrhosis gets worse, the liver begins to fail.

In children with biliary atresia, cirrhosis may cause complications, including portal hypertension. Portal hypertension is high blood pressure in the portal vein, a blood vessel that carries blood from the intestines to the liver.

Portal hypertension may lead to specific complications, including:

- a buildup of fluid in the abdomen, called ascites. Infection of this fluid can be very dangerous.

- enlarged blood vessels, called varices, which can develop in the esophagus, stomach, or both. Varices can break open and cause life-threatening bleeding in the digestive tract.

Liver failure

With liver failure, also called end-stage liver disease, the liver can no longer perform important functions or replace damaged cells. Infants and children with liver failure need a liver transplant to survive.

Biliary atresia diagnosis

To diagnose biliary atresia, a doctor will ask about your infant’s medical and family history, perform a physical exam, and order a series of tests. Experts recommend testing for biliary atresia and other health problems in infants who still have jaundice 3 weeks after birth.

If test results suggest that an infant is likely to have biliary atresia, the next step is surgery to confirm the diagnosis.

Doctors may refer children with suspected biliary atresia to specialists, such as pediatric gastroenterologists, pediatric hepatologists, or pediatric surgeons.

Family and medical history

The doctor will ask about your infant’s family and medical history. The doctor will also ask about symptoms such as jaundice and changes in poop color.

Physical exam

During a physical exam, the doctor may:

- examine the infant’s body for signs of jaundice

- examine the infant’s body for other birth defects that sometimes occur along with biliary atresia

- feel the infant’s abdomen to check for an enlarged liver or spleen, which may be signs of biliary atresia

- check the color of the infant’s stool and urine.

Tests to diagnose biliary atresia

Doctors may order some or all of the following tests to diagnose biliary atresia and rule out other health problems. Doctors may perform several tests because many other diseases can cause signs that are like the signs of biliary atresia.

Blood tests

A health care professional may take a blood sample from the infant and send the sample to a lab. Doctors may use blood tests to measure bilirubin levels and to check for signs of liver disease.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound uses a device called a transducer, which bounces safe, painless sound waves off organs to create images of their structure. Using ultrasound, doctors can rule out other health problems and look for signs that suggest an infant may have biliary atresia. However, an ultrasound cannot confirm a diagnosis of biliary atresia.

Hepatobiliary scan

A hepatobiliary scan is an imaging test that uses a small amount of safe radioactive material to create an image of the liver and bile ducts. The test can show if and where bile flow is blocked.

Liver biopsy

During a liver biopsy, a doctor will take pieces of tissue from the liver. A pathologist will examine the tissue under a microscope to look for signs of damage or disease. A liver biopsy can show whether an infant is likely to have biliary atresia. A biopsy can also help rule out or identify other liver problems.

Surgery to confirm the diagnosis of biliary atresia

During diagnostic surgery, a pediatric surgeon makes a cut in the infant’s abdomen to directly examine the liver and bile ducts. Alternatively, surgeons may use a device called a laparoscope, which is inserted through a small incision and does not require the abdomen to be opened. If the surgeon confirms that the infant has biliary atresia, the surgeon will usually perform surgery to treat biliary atresia right away.

Biliary atresia treatment

Doctors treat biliary atresia with a surgery called the Kasai procedure and eventually, in most cases, a liver transplant. Thanks to advances in treatment, more than 80 to 90 percent of infants with biliary atresia survive to adulthood 9.

Biliary atresia surgery

The Kasai procedure or Kasai hepatoportoenterostomy 10 is usually the first treatment for biliary atresia. The Kasai procedure does not cure biliary atresia. However, if the procedure is successful, it may slow liver damage and delay or prevent complications and the need for a liver transplant. The earlier the procedure is done, the more effective it may be.

During the procedure, a surgeon removes the damaged bile ducts outside the liver. The surgeon uses a loop of the infant’s own small intestine to replace the damaged bile ducts. If the surgery is successful, bile will flow directly from the liver to the small intestine. Within 3 months of the procedure, one has an idea of whether the surgery has worked or not. After a successful surgery, most infants no longer have jaundice and have a reduced risk of developing complications of advancing liver disease.

Complications. After the procedure, a common complication is infection of the liver, called cholangitis . Doctors may prescribe antibiotics after surgery to help prevent this infection. If cholangitis occurs, doctors treat it with antibiotics, usually intravenous (IV) antibiotics given in the hospital.

If the procedure is not successful, the flow of bile will remain blocked. After an unsuccessful procedure, infants will develop complications of biliary atresia and will usually need a liver transplant by age 2.

Even after a successful surgery, most children will slowly develop complications of biliary atresia, over years or decades, and will eventually need a liver transplant. In some cases, after a successful procedure, children never need a liver transplant.

Kasai procedure complications

The most common complications following the Kasai procedure include:

Cholangitis

Direct communication of the intestine with the dystrophic intrahepatic bile ducts, together with poor bile flow, can cause an ascending bacterial cholangitis. This occurs particularly in the first weeks or months after the Kasai procedure in 30%-60% of cases 11. This infection may be severe and sometimes fulminant. There are signs of sepsis (fever or hypothermia, impaired haemodynamic status), recurrent jaundice, acholic stools and perhaps abdominal pain. Diagnosis can be confirmed by analysis of blood cultures and/or liver biopsies 12. Treatment requires IV antibiotics and effective IV resuscitation. In the cases with recurrent and/or late cholangitis, obstruction of the Roux en Y loop or persisting colonisation of intrabiliary cyst should be considered. Recurrent cholangitis without a “surgical” cause may require continuous antibiotic prophylaxis.

Portal hypertension

Portal hypertension occurs in at least two-thirds of the children after porto-enterostomy 13, even in those with complete restoration of bile flow. The most common sites of varices include the oesophagus, stomach, Roux loop and anorectum. If the Kasai operation has clearly failed and the patient displays poor biochemical liver function and persisting jaundice, then liver transplantation is indicated. However, variceal sclerotherapy or band ligation before liver replacement may be necessary. In those cases with good liver function and absence of jaundice, endoscopic therapy may be the only treatment necessary 14. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) are rarely used for this indication due to the young age of the patients, the frequently observed hypoplasia of the portal vein and the possible development of intrahepatic biliary cavities 15. Surgical portosystemic shunts are nowadays rarely indicated, especially when transplantation is available, but should be considered when there is a normal liver function, non-progressive liver disease and life-threatening varices 16. Severe hypersplenism may exceptionally require splenic artery embolisation 17.

Hepatopulmonary syndrome and pulmonary hypertension

Similarly to patients with other causes of spontaneous (cirrhosis or prehepatic portal hypertension) or acquired (surgical) portosystemic shunts, pulmonary arteriovenous shunts may occur even after complete clearance of jaundice (hepatopulmonary syndrome). Gut-derived vasoactive substances that are not cleared by the liver (due to the portosystemic shunts) may be responsible for this complication. Typically, hepatopulmonary syndrome causes hypoxia, cyanosis, dyspnoea and digital clubbing. Diagnosis is confirmed by pulmonary scintigraphy. Pulmonary hypertension can occur in cirrhotic children and may provoke syncope or even sudden death. Diagnosis of pulmonary hypertension is suggested by echocardiography. Liver transplantation reverses pulmonary shunts 18 and can reverse pulmonary hypertension (especially when diagnosed at an early stage) 19.

Intrahepatic biliary cavities

Large intrahepatic biliary cysts may develop several months to years after the Kasai operation, even in patients with complete clearance of jaundice. These cavities may become infected and/or may compress the portal vein, requiring external drainage. Cystoenterostomy 20 or liver transplantation may eventually be required.

Cancers

Hepatocarcinomas, hepatoblastomas 21 and cholangiocarcinomas 22 have been described in the cirrhotic livers of patients with biliary atresia, in childhood or adulthood. Screening for malignancy has to be performed regularly in the follow-up of patients who underwent a successful Kasai operation.

Liver transplant

If biliary atresia leads to serious complications, the infant or child will need a liver transplant. A liver transplant is surgery to remove a diseased or injured liver and replace it with a healthy liver from another person, called a donor.

Most children with biliary atresia eventually need a liver transplant, even after a successful Kasai procedure.

Diet for biliary atresia

Even after treatment with the Kasai procedure, children with biliary atresia may have reduced bile flow to the small intestine and liver damage, leading to:

- problems digesting fats and absorbing fat-soluble vitamins

- loss of appetite

- a faster metabolism and a need for more calories

- low levels of protein, vitamins, and minerals

These problems may cause children with biliary atresia to become malnourished, and they may not grow normally.

What should infants and children with biliary atresia eat?

To make sure infants and children with biliary atresia get enough nutrients and calories, doctors may recommend:

- a special eating plan

- a special formula for formula-fed infants

- supplements, which may be added to breast milk, formula, or food

Supplements for biliary atresia include vitamins—especially fat-soluble vitamins—and medium-chain triglyceride (MCT) oil. MCT oil adds calories to foods and is easier to digest without bile than other fats. Doctors may recommend other types of supplements as well.

If a child isn’t getting enough nutrients from food and supplements taken by mouth, a doctor may recommend using a feeding tube, called a nasogastric feeding tube , to provide high-calorie liquid directly to the stomach. In some cases, children with biliary atresia need to receive nutrition through an intravenous (IV) line. This type of feeding is called total parenteral nutrition (TPN) .

Your child’s doctor or a dietitian can recommend a specific eating plan and supplements for your child.

What should infants and children eat after a liver transplant?

After a liver transplant, most infants and children can eat a healthy, balanced diet that is normal for their age.

Biliary atresia prognosis

The overall prognosis of biliary atresia patients has improved since the early days of paediatric liver transplantation. Nowadays about 90% of biliary atresia patients may hope to survive (Table 1), with a normal quality of life for most of them 3 .

Several prognostic factors have been identified in biliary atresia patients. Some of them are related to characteristics of the disease (and cannot be altered): the prognosis of the Kasai operation is worse when biliary atresia is associated with a polysplenia syndrome 23; when macroscopic obstructive lesions of extra-hepatic biliary remnant are diffuse (prognosis worsens) 24; when histological obliteration of the bile ducts (especially at porta hepatis) is more severe 25; and when liver fibrosis is more extensive at time of the Kasai operation 26.

Other prognostic factors are related to the management of biliary atresia patients and can be improved:

- the chances of success of the Kasai operation decrease when the age at Kasai operation increases 24. It is, therefore, very important to diagnose biliary atresia early.

- accessibility to liver transplantation 27: the mortality while waiting for a liver graft has recently decreased due to the development of surgical techniques that increase the availability of liver grafts: liver graft splitting 28, living related liver donation 29.

- experience of the centre managing biliary atresia patients 30. This point led the British health authorities to centralize all biliary atresia patients from England and Wales in three paediatric liver units 31. In France, a collaborative policy between centres was promoted and a national observatory of biliary atresia was created, in order to standardize therapeutic results nationwide and evaluate the results of this decentralized management.

Table 1. Current prognosis of biliary atresia in France and the United Kingdom.

| France 1997–2002 (271 patients) | UK 1999–2002 (148 patients) [98] | |

| Overall 4-year patient survival | 87% | 89% |

| 4-year survival with native liver after Kasai operation | 43% | 51% |

| 4-year survival after liver transplantation | 89% | 90% |

Biliary atresia life expectancy

Currently, patient survival at 5 and 10 years after liver transplantation is more than 80% 32. In most cases, the quality of life of the transplanted patient is close to normal. Normal somatic growth pattern and physical, sexual and intellectual maturity are usually achieved 33.

Figure 2. Biliary atresia life expectancy

Footnote: Survival with native liver of 271 infants who underwent Kasai operation for biliary atresia between 1968 and 1983 at Bicêtre hospital (Paris)

[Source 34 ] References- Fawaz R, Baumann U, Ekong U, et al. Guideline for the evaluation of cholestatic jaundice in infants: joint recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2017;64(1):154–168.

- Russo P, Rand EB, Loomes KM. Chapter 10: Diseases of the biliary tree. In: Russo P, Ruchelli ED, Piccoli DA, eds. Pathology of Pediatric Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 2014;395–444.

- Chardot C. Biliary atresia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2006;1:28. Published 2006 Jul 26. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-1-28 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1560371/

- Definition & Facts of Biliary Atresia. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/liver-disease/biliary-atresia/definition-facts

- Schwarz KB, Haber BH, Rosenthal P, et al. Extrahepatic anomalies in infants with biliary atresia: results of a large prospective North American multicenter study. Hepatology. 2013;58(5):1724-31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3844083

- Schwarz KB, Haber BH, Rosenthal P, et al. Extrahepatic anomalies in infants with biliary atresia: results of a large prospective North American multicenter study. Hepatology. 2013;58(5):1724–1731.

- Long-term outcomes of biliary atresia with splenic malformation. J Pediatr Surg. 2015 Dec;50(12):2124-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2015.08.040.

- Wang KS. Newborn screening for biliary atresia. Pediatrics. 2015;136(6):e1663–e1669.

- Biliary atresia. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/biliary-atresia

- Kasai M, Suzuki S. A new operation for “non-correctable” biliary atresia, hepatic portoenterostomy. Shujutsu. 1959;13:733–739.

- Burnweit CA, Coln D. Influence of diversion on the development of cholangitis after hepatoportoenterostomy for biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1986;21:1143–1146. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(86)90028-X

- Ecoffey C, Rothman E, Bernard O, Hadchouel M, Valayer J, Alagille D. Bacterial cholangitis after surgery for biliary atresia. J Pediatr. 1987;111:824–849. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3476(87)80195-6

- Ohi R, Mochizuki I, Komatsu K, Kasai M. Portal hypertension after successful hepatic portoenterostomy in biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1986;21:271–274.

- Sasaki T, Hasegawa T, Nakajima K, Tanano H, Wasa M, Fukui Y, Okada A. Endoscopic variceal ligation in the management of gastroesophageal varices in postoperative biliary atresia. J Pediatr Surg. 1998;33:1628–1632. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(98)90595-4

- Rossle M, Siegerstetter V, Huber M, Ochs A. The first decade of the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS): state of the art. Liver. 1998;18:73–89

- Valayer J, Branchereau S. Portal hypertension: porto systemic shunts. In: Stringer MD, Oldham KT, Mouriquand PDE, Howard ER, editor. Pediatric surgery and urology: long term outcomes. London: W.B. Saunders; 1998. pp. 439–446.

- Chiba T, Ohi R, Yaoita M. Partial splenic embolization for hypersplenism in pediatric patients with special reference to its long-term efficacy. In: Ohi R, editor. Biliary atresia. Tokyo: ICOM Associates Inc; 1991. pp. 154–158.

- Yonemura T, Yoshibayashi M, Uemoto S, Inomata Y, Tanaka K, Furusho K. Intrapulmonary shunting in biliary atresia before and after living-related liver transplantation. Br J Surg. 1999;86:1139–1143. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01207.x.

- Losay J, Piot D, Bougaran J, Ozier Y, Devictor D, Houssin D, Bernard O. Early liver transplantation is crucial in children with liver disease and pulmonary artery hypertension. J Hepatol. 1998;28:337–342. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(88)80022-9

- Tsuchida Y, Honna T, Kawarasaki H. Cystic dilatation of the intrahepatic biliary system in biliary atresia after hepatic portoenterostomy. J Pediatr Surg. 1994;29:630–634. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(94)90728-5

- Tatekawa Y, Asonuma K, Uemoto S, Inomata Y, Tanaka K. Liver transplantation for biliary atresia associated with malignant hepatic tumors. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36:436–439. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2001.21600.

- Kulkarni PB, Beatty E., Jr Cholangiocarcinoma associated with biliary cirrhosis due to congenital biliary atresia. Am J Dis Child. 1977;131:442–444.

- Vazquez J, Lopez Gutierrez JC, Gamez M, Lopez-Santamaria M, Murcia J, Larrauri J, Diaz MC, Jara P, Tovar JA. Biliary atresia and the polysplenia syndrome: its impact on final outcome. J Pediatr Surg. 1995;30:485–487. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(95)90062-4.

- Altman RP, Lilly JR, Greenfeld J, Weinberg A, van Leeuwen K, Flanigan L. A multivariable risk factor analysis of the portoenterostomy (Kasai) procedure for biliary atresia: twenty-five years of experience from two centers. Ann Surg. 1997;226:348–355. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199709000-00014.

- Schweizer P, Kirschner HJ, Schittenhelm C. Anatomy of the porta hepatis (PH) as rational basis for the hepatoporto-enterostomy (HPE) Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1999;9:13–18.

- Wildhaber BE, Coran AG, Drongowski RA, Hirschl RB, Geiger JD, Lelli JL, Teitelbaum DH. The Kasai portoenterostomy for biliary atresia: A review of a 27-year experience with 81 patients. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:1480–1485. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(03)00499-8.

- Nio M, Ohi R, Miyano T, Saeki M, Shiraki K, Tanaka K. Five- and 10-year survival rates after surgery for biliary atresia: a report from the Japanese Biliary Atresia Registry. J Pediatr Surg. 2003;38:997–1000. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3468(03)00178-7

- Gridelli B, Spada M, Petz W, Bertani A, Lucianetti A, Colledan M, Altobelli M, Alberti D, Guizzetti M, Riva S, Melzi ML, Stroppa P, Torre G. Split-liver transplantation eliminates the need for living-donor liver transplantation in children with end-stage cholestatic liver disease. Transplantation. 2003;75:1197–1203. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000061940.96949.A1

- Reding R, Chardot C, Paul K, Veyckemans F, Van Obbergh L, De Clety SC, Detaille T, Clapuyt P, Saint-Martin C, Janssen M, Lerut J, Sokal E, Otte JB. Living-related liver transplantation in children at Saint-Luc University Clinics: a seven year experience in 77 recipients. Acta Chir Belg. 2001;101:17–19.

- McKiernan PJ, Baker AJ, Kelly DA. The frequency and outcome of biliary atresia in the UK and Ireland. Lancet. 2000;355:25–29. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03492-3.

- Davenport M, De Ville de Goyet J, Stringer MD, Mieli-Vergani G, Kelly DA, McClean P, Spitz L. Seamless management of biliary atresia in England and Wales (1999–2002) Lancet. 2004;363:1354–1357. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16045-5.

- Bourdeaux C, Tri TT, Gras J, Sokal E, Otte JB, de Ville de Goyet J, Reding R. PELD score and posttransplant outcome in pediatric liver transplantation: a retrospective study of 100 recipients. Transplantation. 2005;79:1273–1276. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200505150-00060

- Midgley DE, Bradlee TA, Donohoe C, Kent KP, Alonso EM. Health-related quality of life in long-term survivors of pediatric liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:333–639. doi: 10.1053/lv.2000.6139.

- Lykavieris P, Chardot C, Sokhn M, Gauthier F, Valayer J, Bernard O. Outcome in adulthood of biliary atresia: a study of 63 patients who survived for over 20 years with their native liver. Hepatology. 2005;41:366–371. doi: 10.1002/hep.20547