What is biofeedback

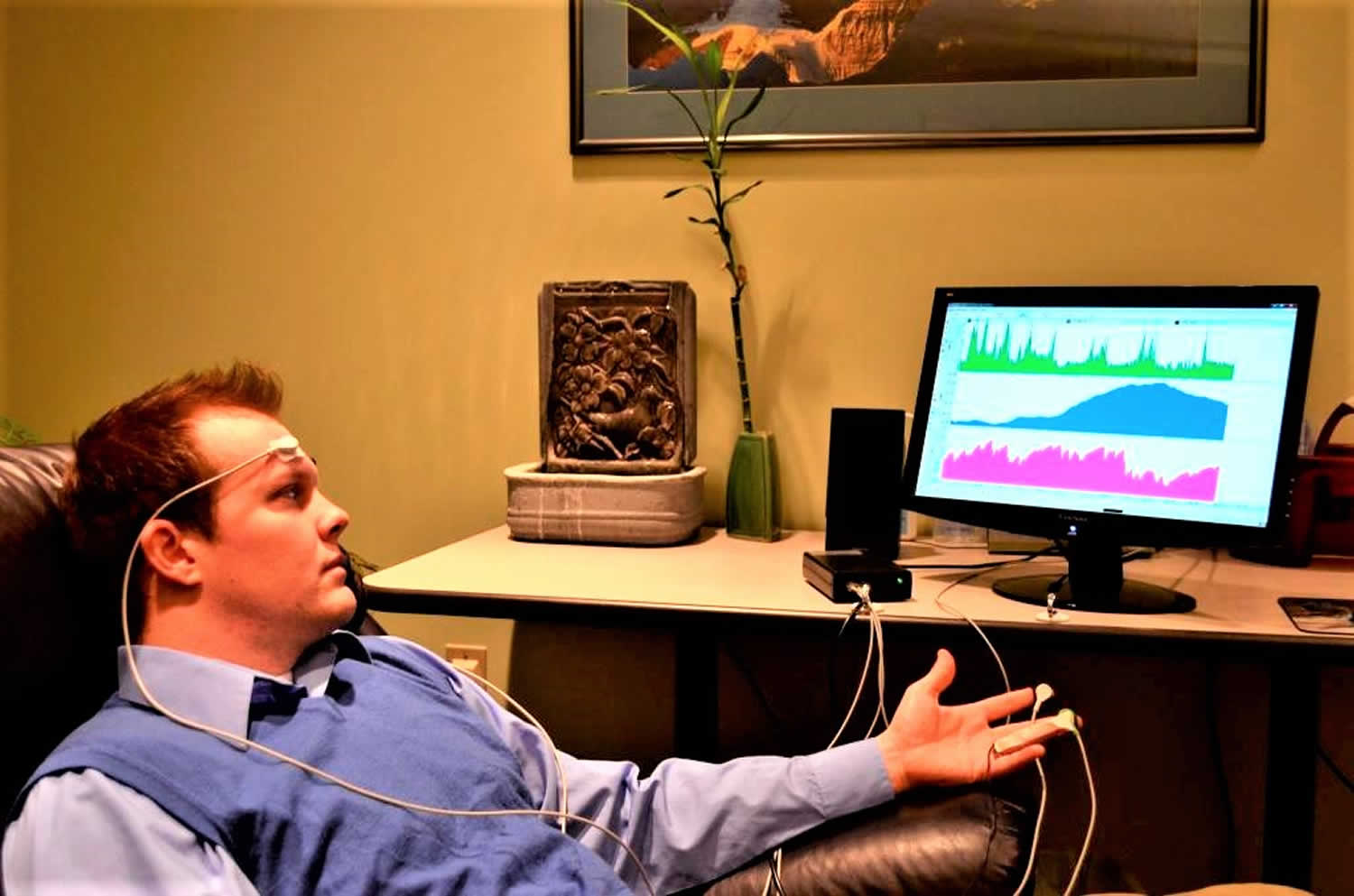

Biofeedback is a self‐regulation technique you can use to learn to voluntarily control your body’s functions, such as your heart rate. The idea of controlling body functions with the mind is not new. Many Eastern philosophies, such as yoga, are based on the belief that meditation and visualization can lead to control over automatic physical processes. With biofeedback, you’re connected to electrical sensors that help you receive information (feedback) about your body (bio). Biofeedback therapy requires specialized equipment to convert physiological signals into meaningful visual and auditory cues, as well as a trained biofeedback practitioner to guide the therapy. Using a screen such as a computer monitor, patients get feedback that helps them develop control over their physiology. Just as looking into a mirror allows you to see and change positions, expressions, etc., biofeedback allows patients to see inside their bodies, with a trained practitioner serving as a guide directing them to use the feedback to regulate their physiology in a healthy direction 1.

Biofeedback helps you focus on making subtle changes in your body, such as relaxing certain muscles, to achieve the results you want, such as reducing pain. In essence, biofeedback gives you the power to use your thoughts to control your body, often to improve a health condition or physical performance.

Biofeedback is generally safe. Biofeedback might not be appropriate for everyone, though. Be sure to discuss it with your doctor first.

In its modern applications, numerous types of biofeedback instruments are available that display the effectiveness of the therapy as it is being done and can be used to monitor the progress of the activity.

Biofeedback is most often used with instruments that measure:

- Blood pressure

- Brain waves

- Breathing rate

- Heart rate and heart rate variability

- Muscle tension

- Skin conductivity of electricity

- Skin temperature

Hooked up with electrodes to electronic equipment, a person’s breathing rate, perspiration, skin temperature, blood pressure, and heartbeat are measured. The results are displayed on a computer screen. Specific devices are used to measure each body change, including:

- Electromyogram (EMG). This is used to measure muscle tension.

- Electrodermal activity (EDA). This is used to measure changes in perspiration rate.

- Finger pulse measurements. These measure blood pressure and heartbeat.

- Electroencephalogram (EEG). This is used to measure electrical activity in the brain.

In addition, both the rhythm and volume of breathing are measured.

Once a person’s body signals are recorded with the electronic devices, a biofeedback technician or computer feedback may recommend both physical and mental exercises to gain control. Biofeedback technicians are trained and nationally certified.

Biofeedback is most helpful to reduce stress and promote relaxation. It is also under investigation for conditions such as urinary incontinence, migraines, and other headaches.

To find a biofeedback therapist, ask your doctor or another health care professional with knowledge of biofeedback therapy to recommend someone who has experience treating your condition. Many biofeedback therapists are licensed in another area of health care, such as nursing or physical therapy, and might work under the guidance of a doctor.

State laws regulating biofeedback practitioners vary. Some biofeedback therapists choose to become certified to show their extra training and experience in the practice.

Ask a potential biofeedback therapist questions before starting treatment, such as:

- Are you licensed, certified or registered?

- What is your training and experience?

- Do you have experience providing feedback for my condition?

- How many biofeedback sessions do you think I’ll need?

- What’s the cost, and is it covered by health insurance?

- Can you provide a list of references?

How does biofeedback work

Biofeedback is a mind-body technique that uses various forms of monitoring devices to create conscious control over physical processes that are normally under automatic control of the body. Biofeedback is a technique that measures bodily functions and gives you information about them in order to help train you to control them. Biofeedback is a non-invasive training and can be helpful for reducing symptoms. Biofeedback may be an option for individuals who are pregnant or can’t tolerate medications for their conditions.

Biofeedback is most often based on measurements of:

- Blood pressure

- Brain waves with an electroencephalograph (EEG)

- Breathing

- Heart rate with an electrocardiograph (ECG)

- Muscle tension with an electromyography (EMG)

- Skin conductivity of electricity with an electrodermograph (EDG)

- Skin temperature

By watching these measurements, you can learn how to change these functions by relaxing or by holding pleasant images in your mind.

Patches, called electrodes, are placed on different parts of your body. They measure your heart rate, blood pressure, or other function. A monitor displays the results. A tone or other sound may be used to let you know when you have reached a goal or certain state.

Your health care provider will describe a situation and guide you through relaxation techniques. The monitor lets you see how your heart rate and blood pressure change in response to being stressed or remaining relaxed.

Biofeedback teaches you how to control and change these bodily functions. By doing so, you feel more relaxed or more able to cause specific muscle relaxation processes.

This may help treat conditions such as:

- Anxiety and insomnia

- Constipation

- Tension and migraine headaches

- Urinary incontinence

- Pain disorders such as headache or fibromyalgia

Types of biofeedback

Your therapist might use several different biofeedback methods. Determining the method that’s right for you depends on your health problems and goals.

Biofeedback methods include:

- Brainwave. This type of method uses scalp sensors to monitor your brain waves using an electroencephalograph (EEG).

- Breathing. During respiratory biofeedback, bands are placed around your abdomen and chest to monitor your breathing pattern and respiration rate.

- Heart rate. This type of biofeedback uses finger or earlobe sensors with a device called a photoplethysmograph or sensors placed on your chest, lower torso or wrists using an electrocardiograph (ECG) to measure your heart rate and heart rate variability.

- Muscle. This method of biofeedback involves placing sensors over your skeletal muscles with an electromyography (EMG) to monitor the electrical activity that causes muscle contraction.

- Sweat glands. Sensors attached around your fingers or on your palm or wrist with an electrodermograph (EDG) measure the activity of your sweat glands and the amount of perspiration on your skin, alerting you to anxiety.

- Temperature. Sensors attached to your fingers or feet measure your blood flow to your skin. Because your temperature often drops when you’re under stress, a low reading can prompt you to begin relaxation techniques.

Biofeedback machines

You can receive biofeedback training in physical therapy clinics, medical centers and hospitals. A growing number of biofeedback machines and programs are also being marketed for home use, including:

- Interactive computer or mobile device programs. Some types of biofeedback devices measure physiological changes in your body, such as your heart rate activity and skin changes, by using one or more sensors attached to your fingers or your ear. The sensors plug into your computer. Using computer graphics and prompts, the devices then help you master stress by pacing your breathing, relaxing your muscles and thinking positive thoughts. Studies show that these types of devices might be effective in improving responses during moments of stress, and inducing feelings of calm and well-being.

- Another type of biofeedback therapy involves wearing a headband that monitors your brain activity while you meditate. It uses sounds to let you know when your mind is calm and when it’s active to help you learn how to control your stress response. The information from each session can then be stored to your computer or mobile device.

- Wearable devices. One type of wearable device involves wearing a sensor on your waist that monitors your breathing and tracks your breathing patterns using a downloadable app. The app can alert you if you’re experiencing prolonged tension, and it offers guided breathing activities to help restore your calm.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) defined a biofeedback device (21 CFR 882.5050) as “biofeedback device is an instrument that provides a visual or auditory signal corresponding to the status of one or more of a patient’s physiological parameters (e.g., brain alpha wave activity, muscle activity, skin temperature, etc.) so that the patient can control voluntarily these physiological parameters.” The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a biofeedback device, Resperate, for reducing stress and lowering blood pressure. Resperate is a portable electronic device that promotes slow, deep breathing.

However, many biofeedback devices marketed for home use aren’t regulated by the Food and Drug Administration. Before trying biofeedback therapy at home, discuss the different types of devices with your doctor to find the best fit.

Be aware that some products might be falsely marketed as biofeedback devices, and that not all biofeedback practitioners are reputable. If a manufacturer or biofeedback practitioner claims that a biofeedback device can assess your organs for disease, find impurities in your blood, cure your condition or send signals into your body, check with your doctor before using it, as it might not be legitimate.

What is biofeedback therapy?

Biofeedback therapy is a process of training as opposed to a treatment 1. Much like being taught how to tie their shoes or ride a bicycle, individuals undergoing biofeedback training must take an active role and practise in order to develop the skill. Rather than passively receiving a treatment, the patient is an active learner. It’s like learning a new language.

Biofeedback, sometimes called biofeedback training, is used to help manage many physical and mental health issues, including:

- Anxiety or stress

- Asthma

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Chemotherapy side effects

- Chronic pain

- Constipation

- Fecal incontinence

- Fibromyalgia

- Headache

- High blood pressure

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Motion sickness

- Raynaud’s disease

- Ringing in the ears (tinnitus)

- Stroke

- Temporomandibular joint disorder (TMJ)

- Urinary incontinence

When a patient comes in for clinical biofeedback therapy, an emphasis is placed on education. As sensors are placed on the patient’s skin, the therapist explains what each sensor will be measuring, assuring the patient that the sensors do not cause any pain or shock but rather are simply recording signals from the body and displaying those signals on the screen. The therapist chooses signal displays which take into account both the needs and limitations of the individual being seen, and then explains each signal. This may be as simple as ‘the green line is muscle tension, the blue line is temperature’, etc 2. Patients are then taught how the signals being displayed relate to their physiology. For example, the therapist may say, ‘Raise your shoulders’ or ‘Scrunch your face,’ using the muscle tension signal on the screen to point out the patient’s physiological responses.

Patients are also shown how their physiology is reactive to mental stimuli, particularly stressful situations. This is often done with a psychophysiological assessment including a series of activities and recoveries. First patients are asked to relax, and then they are asked to engage in a stressful activity such as the Stroop Color–Word Test 3 or the Serial Sevens Test 4 before once again being asked to relax. The therapist can then pause the feedback and show the patient his or her physiological reactivity to the mental task, as well as the extent and speed with which the physiology returned to baseline values. At this point the therapist may explain what the optimal values are for each of the physiological variables being measured as well as how they relate to patient health. For example, the therapist may say, ‘Keeping the green line down below two microvolts means that your muscles are already relaxed’. This may also be related to the patient’s current condition by saying something such as ‘If you practise letting go of the tension in these muscles, then you will experience headaches less frequently or with less intensity’. The therapist may then provide the patient with suggestions of how to use imagery or self‐talk to reduce stress. The final aspect of biofeedback training is reinforcement by the therapist that the patient is doing a good job and is more in control of his or her recovery and wellness.

Biofeedback appeals to people for a variety of reasons:

- It’s noninvasive.

- It might reduce or eliminate the need for medications.

- It might be a treatment alternative for those who can’t tolerate medications

- It might be an option when medications haven’t worked well.

- It might be an alternative to medications for some conditions during pregnancy.

- It helps people take charge of their health.

During the biofeedback therapy

During a biofeedback session, a therapist attaches electrical sensors to different parts of your body. These sensors monitor your body’s physiological state, such as brain waves, skin temperature, muscle tension, heart rate and breathing. This information is fed back to you via cues, such as a beeping sound or a flashing light.

The feedback teaches you to change or control your body’s physiological reactions by changing your thoughts, emotions or behavior. In turn, this can help the condition for which you sought treatment.

For instance, biofeedback can pinpoint tense muscles that are causing headaches. You then learn how to invoke positive physical changes in your body, such as relaxing those specific muscles, to reduce your pain. The ultimate goal with biofeedback is to learn to use these techniques at home on your own.

A typical biofeedback session lasts 60 to 90 minutes. The length and number of sessions are determined by your condition and how quickly you learn to control your physical responses. You might need at least 10 to 15 sessions, which can make it more expensive and time-consuming. Biofeedback might not be covered by insurance.

Biofeedback therapy results

If biofeedback is successful for you, it might help you control symptoms of your condition or reduce the amount of medication you take. Eventually, you can practice the biofeedback techniques you learn on your own. You might need to continue with standard treatment for your condition, though.

Keep in mind that learning biofeedback can take time and, if it’s not covered by health insurance, it can be expensive.

Does biofeedback therapy work?

In 2001, a Task Force of the Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback and the Society for Neuronal Regulation outlined criteria for levels of evidence‐based clinical efficacy of psychophysiological interventions 5. The official standards for inclusion of research studies in this task force report are described below.

Level 1: Not empirically supported

- Evidence for Level 1 efficacy is supported only by anecdotal reports and/or case studies which are not peer reviewed.

Level 2: Possibly efficacious

- Evidence for Level 2 efficacy is supported by at least one study of sufficient statistical power with well‐identified outcome measures but which lacks random assignment to a control condition internal to the study.

Level 3: Probably efficacious

- Evidence for Level 3 efficacy is supported by multiple observational, clinical, wait list controlled, within‐subject and intrasubject replication studies that demonstrate efficacy.

Level 4: Efficacious

Evidence for Level 4 efficacy meets all of the following criteria:

- in a comparison with a no‐treatment control group, alternative treatment group, or sham (placebo) control utilising randomised assignment, the investigational treatment is shown to be statistically significantly superior to the control condition, or the investigational treatment is equivalent to a treatment of established efficacy in a study with sufficient power to detect moderate differences and

- the studies have been conducted with a population treated for a specific problem, for whom inclusion criteria are delineated in a reliable, operationally defined manner and

- the study used valid and clearly specified outcome measures related to the problem being treated and

- the data are subjected to appropriate data analysis and

- the diagnostic and treatment variables and procedures are clearly defined in a manner that permits replication of the study by independent researchers and

- the superiority or equivalence of the investigational treatment has been shown in at least two independent research settings.

Level 5: Efficacious and specific

Evidence for Level 5 efficacy meets all of the Level 4 criteria and, in addition, the investigational treatment has been shown to be statistically superior to credible sham therapy, pill, or alternative bona fide treatment in at least two independent research settings.

Efficacy ratings for specific conditions

Using the criteria detailed above, Yucha and Montgomery7 rated the current evidence on the efficacy of biofeedback training on various diseases and reported this in 2008 5. These ratings are summarized in Table 1. Keep in mind that if a condition has a lower efficacy rating, this does not suggest that biofeedback is not helpful in that condition, but rather that relevant research has not yet been conducted. Also, when combined with conventional medical management, an individual may very much benefit from a ‘possibly efficacious’ biofeedback application. An initial evaluation can usually reveal whether physiology monitored by biofeedback is outside normal limits and whether correcting it is likely to help the symptoms or disorder. For example, someone with a tension headache but normal electromyogram (EMG) readings from the trapezius and forehead sites probably won’t benefit from EMG biofeedback, but someone with elevated readings probably would.

Table 1. Efficacy ratings for biofeedback training on various medical conditions

| Level 5 Efficacious and specific | Level 2 Possibly efficacious |

| Urinary incontinence (females)6 | Asthma7 |

| Autism8 | |

| Level 4 Efficacious | Bell’s palsy9 |

| Anxiety10 | Cerebral palsy11 |

| ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) 12 | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease13 |

| Chronic pain14 | Coronary artery disease15 |

| Constipation (adult)16 | Cystic fibrosis17 |

| Epilepsy18 | Depressive disorders19 |

| Headache (adult)20 | Erectile dysfunction21 |

| Hypertension22 | Fibromyalgia/chronic fatigue syndrome23 |

| Motion sickness24 | Hand dystonia25 |

| Raynaud’s disease26 | Irritable bowel syndrome27 |

| Temporomandibular disorder28 | Post‐traumatic stress disorder29 |

| Repetitive strain injury30 | |

| Level 3 Probably efficacious | Respiratory failure: mechanical ventilation31 |

| Alcoholism/substance abuse32 | Stroke33 |

| Arthritis34 | Tinnitus35 |

| Diabetes mellitus36 | Urinary incontinence (children)37 |

| Faecal incontinence38 | |

| Headache (pediatric)39 | Level 1 Not empirically supported |

| Insomnia40 | Eating disorders41 |

| Traumatic brain injury42 | Immune function43 |

| Urinary incontinence (males)44 | Spinal cord injury45 |

| Vulvar vestibulitis46 | Syncope47 |

- Frank DL, Khorshid L, Kiffer JF, Moravec CS, McKee MG. Biofeedback in medicine: who, when, why and how? Mental Health in Family Medicine. 2010;7(2):85-91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2939454/

- Schwartz MS, Andrasik F. Biofeedback: a practitioner’s guide. New York: Guilford Press, 2003.

- Half a century of research on the Stroop effect: an integrative review. MacLeod CM. Psychol Bull. 1991 Mar; 109(2):163-203.

- Serial Sevens Test. Schneider L. Arch Intern Med. 1983 Mar; 143(3):612.

- Yucha C, Montgomery D. Evidence‐Based Practice in Biofeedback and Neurofeedback. Wheat Ridge: Association for Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 2008.

- Burgio KL, Locher JL, Goode PS, et al. Behavioral vs drug treatment for urge urinary incontinence in older women: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association 1998;280:1995–2000

- Ritz T, Dahme B, Roth WT. Behavioral interventions in asthma: biofeedback techniques. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2004;56:711–20

- Coben R, Padolsky I. Assessment‐guided neurofeedback for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Neurotherapy 2007;11:5–19

- Dalla Toffola E, Bossi D, Buonocore M, et al. Usefulness of biofeedback/EMG in facial palsy rehabilitation. Disability and Rehabilitation 2005;27:809–15

- Rice KM, Blanchard EB, Purcell M. Biofeedback treatments of generalized anxiety disorder: preliminary results. Biofeedback and Self‐Regulation 1993;18:93–105

- Bolek JE. A preliminary study of modification of gait in real time using surface electromyography. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback 2003;28:129–38

- Monastra VJ, Lynn S, Linden M, et al. Electroencephalographic biofeedback in the treatment of attention‐deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback 2005;30:95–114

- Giardino ND, Chan L, Borson S. Combined heart rate variability and pulse oximetry biofeedback for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: preliminary findings. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback 2004;29:121–33

- Corrado P, Gottlieb H, Abdelhamid MH. The effect of biofeedback and relaxation training on anxiety and somatic complaints in chronic pain patients. American Journal of Pain Management 2003;13:133–9

- Del Pozo JM, Gevirtz RN, Scher B, et al. Biofeedback treatment increases heart rate variability in patients with known coronary artery disease. American Heart Journal 2004;147:E11

- Bassotti G, Chistolini F, Sietchiping‐Nzepa F, et al. Biofeedback for pelvic floor dysfunction in constipation. BMJ 2004;328:393–6

- Delk KK, Gevirtz R, Hicks DA, et al. The effects of biofeedback‐assisted breathing retraining on lung functions in patients with cystic fibrosis. Chest 1994;105:23–8

- Sterman MB. Basic concepts and clinical findings in the treatment of seizure disorders with EEG operant conditioning. Clinical Electroencephalography 2000;31:45–55

- Karavidas MK, Lehrer OM, Vaschillo E, et al. Preliminary results of an open‐label study of heart rate variability biofeedback for the treatment of major depression. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback 2007;32:19–30

- Arena JG, Bruno GM, Hannah SL, et al. Comparison of frontal electromyographic biofeedback training, trapezius electromyographic biofeedback training, and progressive muscle relaxation therapy in the treatment of tension headache. Headache 2001;35:411–19

- Van Kampen M, de Weerdt W, Claes H, et al. Treatment of erectile dysfunction by perineal exercise, electromyographic biofeedback, and electrical stimulation. Physical Therapy 2003;83:536–43

- Linden W, Moseley JV. The efficacy of behavioral treatments for hypertension. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback 2006;31:51–63

- Mueller HH, Donaldson CC, Nelson DV, et al. Treatment of fibromyalgia incorporating EEG‐driven stimulation: a clinical outcomes study. Journal of Clinical Psychology 2001;57:933–52

- Stout CS, Toscano W, Cowings PS. Reliability of psychophysiological responses across multiple motion sickness stimulation tests. Journal of Vestibular Research 1995;5:25–33

- Deepak KK, Behari M. Specific muscle EMG biofeedback for hand dystonia. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback 1999;24:267–80

- Karavidas MK, Tsai PS, Yucha C, et al. Thermal biofeedback for primary Raynaud’s phenomenon: a review of the literature. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback 2006;31:203–16

- Schwartz SP, Taylor AC, Scharff L, et al. Behaviorally treated irritable bowel syndrome patients: a four‐year follow‐up. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1990;28:331–5

- Crider A, Glaros AG, Gevirtz RN. Efficacy of biofeedback‐based treatments for temporomandibular disorders. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback 2005;30:333–45

- Silver SM, Brooks A, Obenchain J. Treatment of Vietnam War veterans with PTSD: a comparison of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, biofeedback, and relaxation training. Journal of Traumatic Stress 1995;8:337–42

- Peper E, Gibney KH, Wilson VE. Group training with healthy computing practicing to prevent repetitive strain injury (RSI): a preliminary study. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback 2004;29:279–87

- Holliday JE, Lippmann M. Reduction in ventilatory response to CO2 with relaxation feedback during CO2 breathing for ventilator patients. Chest 2003;124:1500–11

- Sokhadze TM, Cannon RL, Trudeau DL. EEG biofeedback as a treatment for substance use disorders: review, rating of efficacy, and recommendations for further research. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback 2008;33:1–28

- Woodford H, Price C. EMG biofeedback for the recovery of motor function after stroke. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2006;2:CD004585

- Young LD, Bradley LA, Turner RA. Decreases in health care resource utilization in patients with rheumatoid arthritis following a cognitive behavioral intervention. Biofeedback and Self‐Regulation 1995;20:259–68

- Heinecke K, Weise C, Schwarz K, et al. Physiological and psychological stress reactivity in chronic tinnitus. Journal of Behavioral Medicine 2008;31:179–88

- Jablon SL, Naliboff BD, Gilmore SL, et al. Effects of relaxation training on glucose tolerance and diabetic control in type II diabetes. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback 1997;22:155–69

- Khen‐Dunlop N, Van Egroo A, Bouteiller C, et al. Biofeedback therapy in the treatment of bladder overactivity, vesico‐ureteral reflux, and urinary tract infection. Journal of Pediatric Urology 2006;2:24–9

- Solomon MJ, Pager CK, Rex J, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of biofeedback with anal manometry, transanal ultrasound, or pelvic floor retraining with digital guidance alone in the treatment of mild to moderate fecal incontinence. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum 2003;46:703–10

- Arndorfer RE, Allen KD. Extending the efficacy of a thermal biofeedback treatment package to the management of tension‐type headaches in children. Headache 2001;41:183–92

- NIH Technology Assessment Panel on Integration of Behavioral and Relaxation Approaches into the Treatment of Chronic Pain and Insomnia Integration of behavioral and relaxation approaches into the treatment of chronic pain and insomnia. Journal of the American Medical Association 1996;276:313–18

- Pop Jordanova N. Psychological characteristics and biofeedback mitigation in preadolescents with eating disorders. Pediatrics International 2000;42:76–81

- Hammond DC. Can LENS neurofeedback treat anosmia resulting from a head injury? Journal of Neurotherapy 2007;11:57–62

- Gruber BL, Hersh SP, Hall NR, et al. Immunological responses of breast cancer patients to behavioral interventions. Biofeedback and Self‐Regulation 1993;18:1–22

- Van Kampen M, de Weerdt W, Van Poppel H, et al. Effect of pelvic‐floor re‐education on duration and degree of incontinence after radical prostatectomy: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2000;355:98–102

- Brucker BS, Bulaeva NV. Biofeedback effect on electromyography responses in patients with spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 1996;77:133–7

- Glazer HI, Rodke G, Swencionis C, et al. Treatment of vulvar vestibulitis syndrome with electromyographic biofeedback of pelvic floor musculature. Journal of Reproductive Medicine 1995;40:283–90

- McGrady AV, Kern‐Buell C, Bush E, et al. Biofeedback‐assisted relaxation therapy in neurocardiogenic syncope: a pilot study. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback 2003;28:183–92