Glasgow Blatchford score

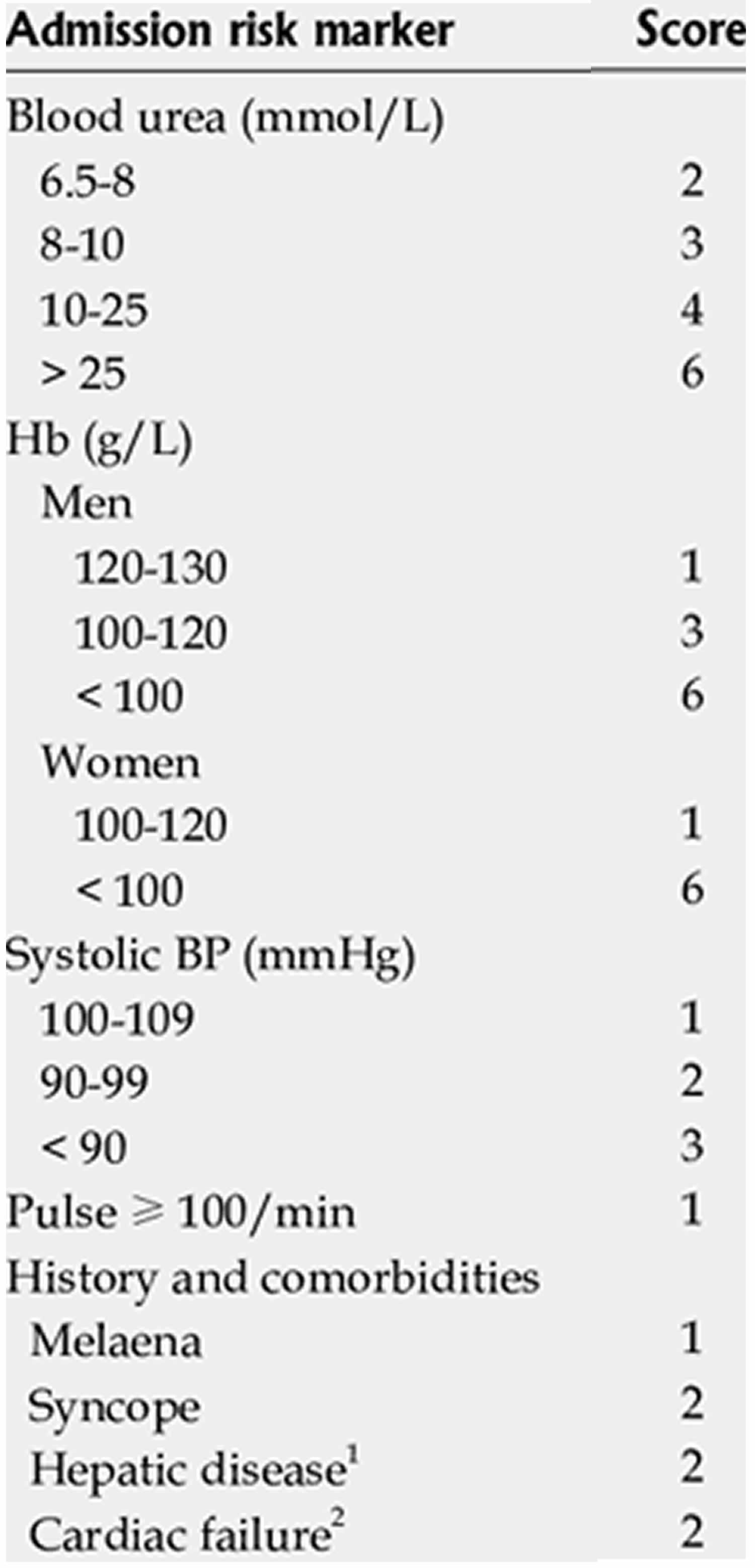

Glasgow Blatchford score was developed in 2000 to predict the need for hospital-based intervention (transfusion, endoscopic therapy or surgery) or death following upper-gastrointestinal bleeding 1. The Glasgow–Blatchford score considers both clinical features and laboratory data (Table 1) 1. Patients with a Glasgow Blatchford score of 0 are considered to be at low risk, and some clinicians recommend that this subgroup of patients could be managed as outpatients, as they do not require early endoscopy 2. Nevertheless, the classification of patients as low risk might not always be accurate. A retrospective study, in which Glasgow Blatchford scores were used to reassess the need for inpatient or outpatient management, found that outpatients had a higher mortality rate than inpatients after 30 days, suggesting that initial assessment was not conducted properly 3.

As the Glasgow–Blatchford score enables the identification of patients who might need intervention, this score is considered to be preferable to the pre-endoscopic clinical Rockall score (not to be confused with the complete Rockall score, which includes both clinical and endoscopic variables, such as diagnosis of the lesion and stigmata of recent hemorrhage) 4, which can only accurately predict the risk of mortality and is less accurate than the Glasgow–Blatchford score for predicting rebleeding or the need for surgery 5. Nevertheless, the pre-endoscopic Rockall score is better than the complete Rockall score for prediction of rebleeding and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and variceal bleeding (at least among patients with upper-gastrointestinal bleeding) 6.

Although the use of such scores is strongly encouraged by professional organizations, such as the British Society of Gastroenterology 7, whose guidelines advise that all patients with suspected upper-gastrointestinal bleeding should undergo risk scoring as part of their initial assessment on presentation, the benefit of these scores in daily clinical practice has been questioned. Insufficient validation or complexity of use have been cited as problems with these scoring systems 8. An independent team of researchers who conducted validation studies of both the Glasgow Blatchford score and Rockall scores (both the pre-endoscopic and complete scores) did not recommend their use in the clinical setting 9.

Despite the existence of these predictive scores the clinical endoscopist’s judgment remains crucial in assessing the patient’s actual level of risk 10, as endoscopic predictors of an increased risk of rebleeding and mortality include active bleeding, an ulcer size >2 cm, ulcers located on the lesser curve of the stomach or in the posterior or superior duodenum 11 and the presence of high-risk stigmata, factors that are not all included in the complete Rockall score 12. Categories of high risk lesions include actively spurting (Forrest class Ia), oozing blood (Forrest class Ib), nonbleeding visible vessels (Forrest class IIa) and adherent clot (Forrest class IIb) 11. Types of low-risk lesions include flat, pigmented spots (Forrest class IIc) and clean-based ulcers (Forrest class III) 13.

Table 1. Glasgow Blatchford score

Footnote: Total Glasgow Blatchford score (0–23). Patients with scores >0 are considered to be at high risk.

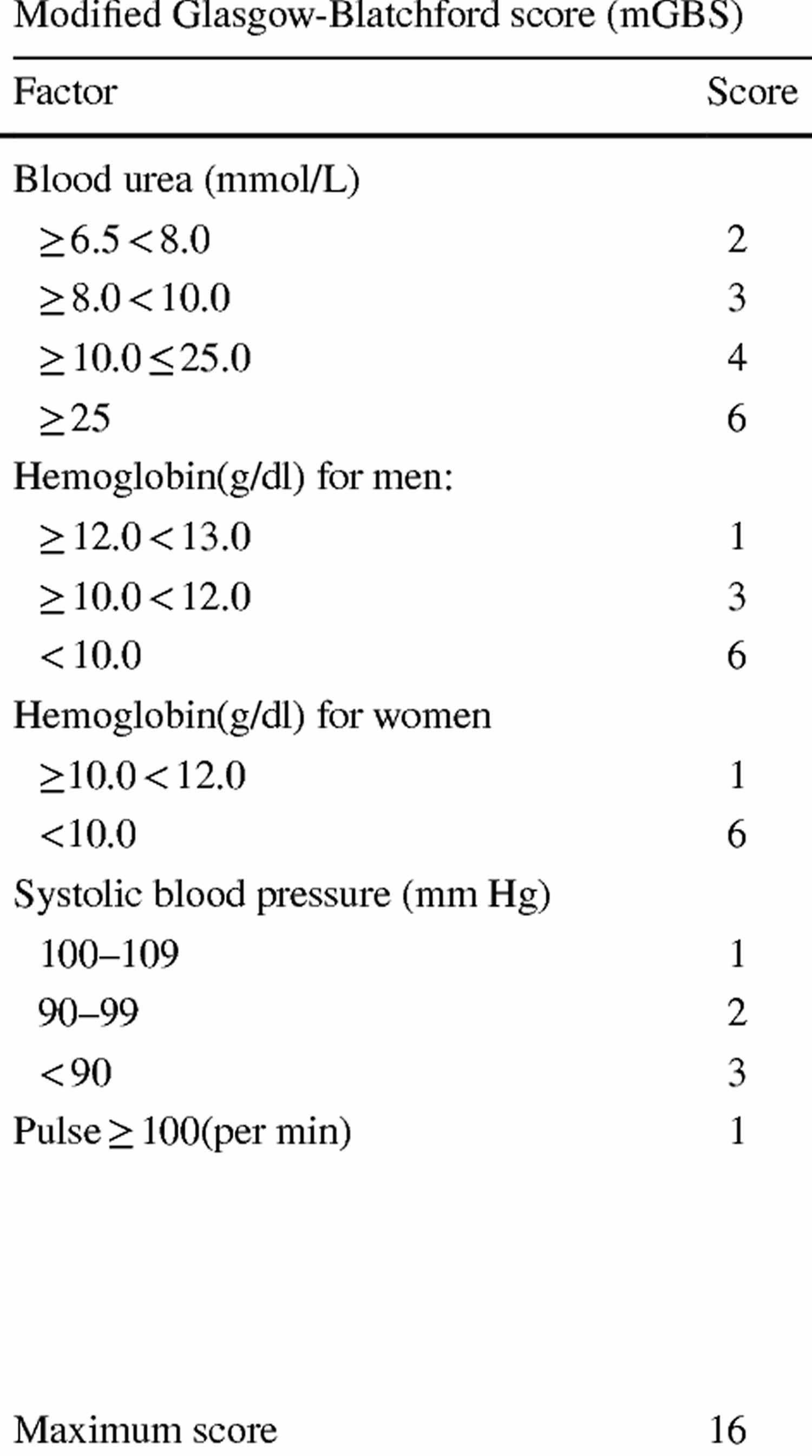

Table 2. Modified Glasgow Blatchford score

Footnote: Glasgow Blatchford score and modified Glasgow Blatchford score scoring systems have similar accuracy in prediction of the probability of re-bleeding, need for blood transfusion, surgery and endoscopic intervention, hospitalization in intensive care unit, and mortality of patients with acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding 14.

Blatchford score interpretation

Glasgow–Blatchford score is a multiple logistic regression-based scoring system (Table 1) that was designed to predict the need for hospital-based intervention (transfusion, endoscopic therapy or surgery) or death in patients presenting with an upper-gastrointestinal bleeding and, therefore, enables appropriate resources to be allocated to critically ill patients 15. The Glasgow-Blatchford Score has been shown to be accurate at predicting the need for intervention and death in acute upper-gastrointestinal bleeding in a variety of populations 16. For example, the results of one study suggested that patients with a Glasgow–Blatchford score above the threshold value of 12 are the most likely to benefit from early endoscopy 17. UK National Institute for health and Care Excellence guidelines have recommended early discharge without endoscopy for patients with a Blatchford score of 0 due to the high negative predictive value of the Glasgow Blatchford score and therefore the safety of discharging patients who have a Glasgow Blatchford score of 0 18. However, this cut-off has a limited sensitivity in that only 3%–22% of patients in different populations actually score Glasgow Blatchford score=0, and many patients scoring >0 have no intervention and do not die so could be safely discharged 19.

Up to 60% of patients who present to the emergency department with an acute upper gastrointestinal bleed are at low risk of requiring intervention or of dying within 30 days. UK National Institute for health and Care Excellence guidelines have recommended early discharge without endoscopy for patients with an acute upper-gastrointestinal bleeding and a Glasgow-Blatchford Score of 0 20. However, this low-risk cut-off has a limited sensitivity in that only 3%–22% of patients score 0 20. International guidelines 21, a few observational and one prospective discharge study 22, have proposed extending the low-risk threshold of the Glasgow Blatchford score to ≤1 or ≤2, with or without an age modification, for discharging patients with an acute upper-gastrointestinal bleeding. These studies demonstrated an ability to identify a higher percentage of low-risk patients (19%–54%) than a cut-off of 0 with a low risk of adverse events. However, one study showed that an extension to ≤2 came at a cost of an increased incidence of adverse events of 7.5% 23. There is therefore controversy as to the optimal Glasgow Blatchford score cut-off for discharge and little evidence on how an extended score performs in routine clinical practice when clinicians use the cut-off to discharge patients with acute upper-gastrointestinal bleeding 20.

What are the new findings?

In this study 20, clinicians using an extended Glasgow Blatchford score score of ≤1 for risk stratification were able to almost double the percentage of patients who could be safely discharged from the emergency department with an acute upper-gastrointestinal bleeding in comparison with a cut-off of 0. This adds weight to the recommendations made in recent international guidelines. A Glasgow Blatchford score cut-off of ≤2 was associated with an adverse outcome in 8% of cases 20.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

Use of an extended Glasgow Blatchford score cut-off of ≤1 has the potential to significantly increase the number of patients with an acute upper-gastrointestinal bleeding who could be discharged from the emergency department, which would, in turn, free up inpatient beds and save costs.

References- Blatchford O, Murray WR, Blatchford M. A risk score to predict need for treatment for upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Lancet 2000; 356: 1318-1321

- Chiu, P. W. & Sung, J. J. Acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 26, 425–428 (2010).

- Cooper, G. S., Kou, T. D. & Wong, R. C. Outpatient management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage: unexpected mortality in Medicare beneficiaries. Gastroenterology 136, 108–114 (2009).

- Rockall, T. A., Logan, R. F., Devlin, H. B. & Northfield, T. C. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Gut 38, 316–321 (1996).

- Enns, R. A. et al. Validation of the Rockall scoring system for outcomes from non-‑variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding in a Canadian setting. World J. Gastroenterol. 12, 7779–7785 (2006).

- Sarwar, S. et al. Predictive value of Rockall score for rebleeding and mortality in patients with variceal bleeding. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 17, 253–256 (2007).

- British Society of Gastroenterology. Scope for improvement: a toolkit for a safer upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) service.

- Abe, Y. et al. Education and imaging. Gastrointestinal: aneurysmal artery in a gastric ulcer after endoscopic hemostasis. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 24, 323 (2009).

- Chandra, S. et al. External validation of the Glasgow–Blatchford Bleeding Score and the Rockall Score in the US setting. Am. J. Emerg. Med. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2011.03.010.

- Farooq, F. T., Lee, M. H., Das, A., Dixit, R. & Wong, R. C. Clinical triage decision vs risk scores in predicting the need for endotherapy in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 30, 129–134 (2010).

- Gralnek, I. M., Barkun, A. N. & Bardou, M. Management of acute bleeding from a peptic ulcer. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 928–937 (2008).

- Barkun, A. N. et al. International consensus recommendations on the management of patients with nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Ann. Intern. Med. 152, 101–113 (2010).

- Forrest, J. A., Finlayson, N. D. & Shearman, D. J. Endoscopy in gastrointestinal bleeding. Lancet 2, 394–397 (1974).

- Shahrami A, Ahmadi S, Safari S. Full and Modified Glasgow-Blatchford Bleeding Score in Predicting the Outcome of Patients with Acute Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding; a Diagnostic Accuracy Study. Emerg (Tehran). 2018;6(1):e31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6036534

- Stanley, A. J. et al. Outpatient management of patients with low-‑risk upper‑gastrointestinal haemorrhage: multicentre validation and prospective evaluation. Lancet 373, 42–47 (2009).

- Stanley AJ, Laine L, Dalton HR, et al. Comparison of risk scoring systems for patients presenting with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: international multicentre prospective study. BMJ. 2017;356:i6432. Published 2017 Jan 4. doi:10.1136/bmj.i6432 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5217768

- Lim, L. G. et al. Urgent endoscopy is associated with lower mortality in high-‑risk but not low‑risk nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy 43, 300–306 (2011).

- Acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding in over 16s: management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg141/chapter/1-Guidance

- Stanley AJ, Ashley D, Dalton HR, et al. Outpatient management of patients with low-risk upper-gastrointestinal haemorrhage: multicentre validation and prospective evaluation. Lancet 2009;373:42–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61769-9

- Banister T, Spiking J, Ayaru L. Discharge of patients with an acute upper gastrointestinal bleed from the emergency department using an extended Glasgow-Blatchford Score. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2018;5(1):e000225. Published 2018 Aug 30. doi:10.1136/bmjgast-2018-000225 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6135483

- Sung JJ, Chiu PC, Chan FKL, et al. Asia-Pacific working group consensus on non-variceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding: an update 2018. Gut 2018. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-316276

- Mustafa Z, Cameron A, Clark E, et al. Outpatient management of low-risk patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding: can we safely extend the Glasgow Blatchford Score in clinical practice? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;27:512–5. 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000333

- Laursen SB, Hansen JM, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB. The Glasgow Blatchford score is the most accurate assessment of patients with upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:1130–5. 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.06.022