Pyelolithotomy

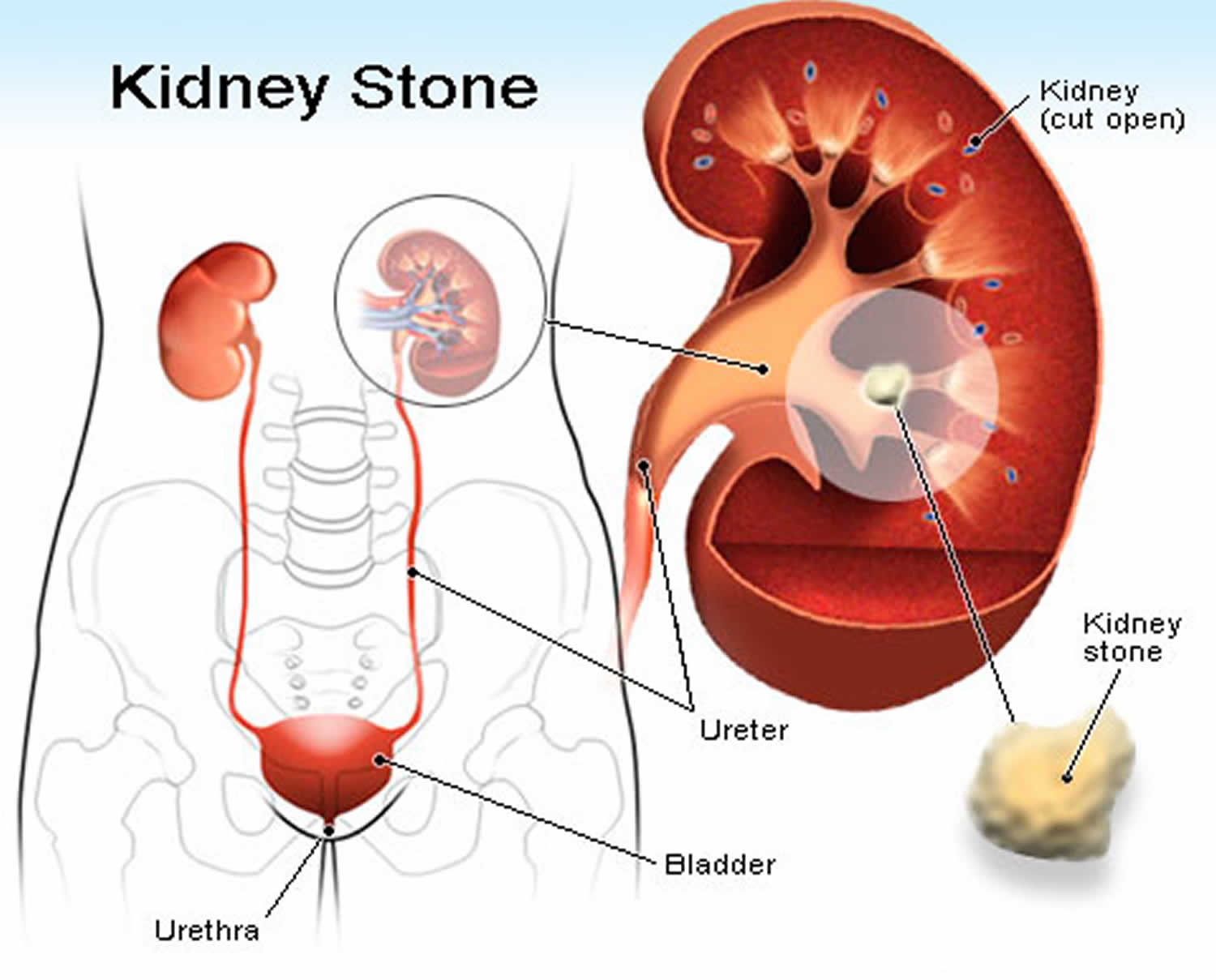

Pyelolithotomy means the removal of stone from the renal pelvis. Since the advent of extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) and percutaneous nephropyelolithotomy, pyelolithotomy is becoming an uncommon surgery in most developing countries 1. However, before these newer technologies, pyelolithotomy was the procedure of choice for stones within the renal pelvis, including stones that demonstrated minimal invasion into calyces and infundibulum. Pyelolithotomy differs from an anatrophic nephrolithotomy, as the anatrophic nephrolithotomy allows for greater access to calyces and allows for repair of infundibulum and calyces 1. Anatrophic nephrolithotomy is indicated for large multiple-branched staghorn calculi with infundibular stenosis.

Extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy (ESWL) is clearly noninvasive, but it may necessitate (1) a cystoscopy and the insertion of a stent to drain the kidney or (2) a nephrostomy in some cases involving infection. extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy is associated with less morbidity than pyelolithotomy, but the overall failure rate and the amount of residual stone fragments are higher. Lower pole stones fragments do not flush out of the renal unit as readily as midpole and upper pole fragments.

Percutaneous nephropyelolithotomy is a highly technical procedure and requires some experience for optimal results. At some facilities, these procedures require the teamwork of a radiologist and a urologist. Morbidity is higher than with extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy, but residual stone fragments are less common. The stone-free rate associated with percutaneous nephrolithotomy is 78%; extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy, 54%.

The 2004 American Urological Association guidelines recommend that staghorn smaller than 2500 mm² with normal renal anatomy should be treated with percutaneous nephrolithotomy as first-line treatment and with extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy as a follow-up procedure.

Pyelolithotomy continues to have a role in the management of renal pelvic stones in areas where extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy and percutaneous nephrolithotomy are not feasible because of the lack of equipment or expertise. Pyelolithotomy is also indicated when the patient’s condition does not permit transfer.

Indications for pyelolithotomy include minimally branched staghorn stones in the renal pelvis of complex collecting systems and excessive morbid obesity. Pyelolithotomy is also appropriate in patients who are undergoing major open abdominal or retroperitoneal surgical procedures for other indications; the most common concomitant procedure is open pyeloplasty for ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction.

Although it is now considered overly invasive for routine use, pyelolithotomy continues to have a role in certain cases. Criteria include the size of the stone 2, the need for concomitant open surgery, and an inaccessibility to extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy or percutaneous nephropyelolithotomy. Current guidelines advocate pyelolithotomy or anatrophic nephrolithotomy when stone burden is greater than 2500 mm², in cases of extreme morbid obesity, or when the patient presents with a complex collecting system.

Other indications are relative and include failure of stone clearance via percutaneous nephrolithotomy, ureteroscopy, or extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy due to difficult extraction, stone composition (ie, cystine), or anatomy (ie, ectopic, pelvic, or horseshoe kidney). Pyelolithotomy is also indicated in combination with pyeloplasty, without increasing morbidity or decreasing the success rate 3.

Indications for stone removal (possible pyelolithotomy) include sepsis, severe flank pain, obstruction with impending parenchymal renal loss, and hematuria. Patients who present for pyelolithotomy also meet the criteria as outlined above.

Pyelolithotomy contraindications

Pyelolithotomy is absolutely contraindicated in patients in a poor general medical condition or those with severe kyphoscoliosis. Only consider this surgery when all other options fail.

Relative contraindications include branched staghorn calculi with infundibular stenosis and stones in the calices. These conditions may be approached using the Boyce anatrophic nephrolithotomy or calycelectomy.

Pyelolithotomy surgery

Pyelolithotomy is an open surgical procedure in cases involving a stone in the renal pelvis. This was a common procedure until the development of extracorporeal shockwave treatment, percutaneous nephrolithotomy, and ureteroscopic laser lithotripsy. However, pyelolithotomy continues to be performed when other modalities fail or when proper facilities are unavailable.

A plain x-ray film of the abdomen (KUB) is essential preoperatively because kidney stones are notorious for moving. Kidney position is always higher than visualized on the x-ray film; always incise above the site noted. Always assume more than one stone is present in the renal pelvis. Make a bigger incision to gain better exposure. Be prepared to take intraoperative x-ray films.

The pyelolithotomy surgical approach is generally through the flank but also may be via a transabdominal approach (in children when concomitant ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction repair is planned) or through a posterior lumbotomy.

Use endotracheal general anesthesia. Insert a Foley catheter. Position the patient in a jack-knife kidney position with the table flexed so that the flank muscles are tight. The kidney bridge may be raised, but the author does not use it often.

Take precautions to protect the auxiliary nerve plexus by placing soft towels under the armpit. Also, do not flex the contralateral knee joint more than 50° to avoid deep vein thrombosis. Finally, apply knee-high stockings preoperatively or use mechanical calf compression devices in order to prevent deep vein thromboses and phlebitis.

The surgeon should position the patient and not rely on the nurse or assistant. The incision may be costal, intercostal, or subcostal, but remember that the kidney is always higher than estimated. Incise the skin over the 12th rib or between the 11th and 12th ribs. Be generous in the skin incision.

Start the incision 3 inches from the spine to the xiphisternum. Do not angle towards the umbilicus, but keep it close to the costal margin. Cut the subcutaneous fat with electrocautery current, which helps limit bleeding. Approach the 12th rib. The intercostal vessels are at the inferior margin of the rib. Incise the periosteum longitudinally with diathermy current or a knife. Elevate using the periosteal elevator.

Resect the rib from the tip to the base of the rib with a rib cutter. The rib may be cut without dissecting the periosteum. Use bone wax to seal the proximal end of the rib, which otherwise tends to slowly ooze. If bleeding occurs, do not cauterize. If necessary, dissect the subcostal nerve and ligate the intercostal vessels.

Incise the periosteum. The pleural cavity may be entered, but if this occurs, do not panic; ask the anesthesiologist to help hyperinflate the lungs after suturing the pleura (with a watertight closure).

Incise the abdominal muscles by diathermy current over the 2 fingers inserted inside, pushing the peritoneum medially. Do not curve the incision towards the pubis; incise towards the xiphisternum (ie, because kidney is always higher than estimated).

Palpate the kidney inside the Gerota fascia. Lift the kidney from the psoas muscle. Identify the ureter lying over the psoas muscle and posterior to the peritoneum. The spleen and liver are intraperitoneal organs. If they are visualized, close the tear in the peritoneum.

Incise the Gerota fascia vertically; diathermy may be used. Dissect the kidney upper pole, lower pole, and posterior aspect. Trace the ureter upwards (a stent is useful). If the ureter is not found, examine the peritoneum from the pelvic brim upwards. Often, the ureter is pushed with the peritoneum. Also, gonadal vessels may be easily mistaken for the ureter; aspirate when in doubt.

Dissect the ureter, and place umbilical tape or a vessel loop behind it. The renal pelvis can be reached by following the ureter upwards. Look for vessels crossing the ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) . Expose the posterior aspect of the pelvis using sharp and blunt dissection.

Remain outside the renal capsule when dissecting the kidney. Do not use blunt dissection because adhesions can tear the renal capsule and cause more bleeding, which obscures the operative field.

The renal pelvis may be intrarenal or extrarenal. For an extrarenal pelvis, insert 2 stay sutures of 3-0 chromic catgut or 5-0 synthetic absorbable suture. Make a transverse incision with a knife between the stay sutures. The incision can be extended into the calyx or, if needed, can be converted into a T incision by crossing the ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) .

If the stone is very large, a Gil-Vernet procedure can be performed (extended pyelolithotomy). The dissection is continued into the sinus by Kuttner (peanut). A vein retractor is very useful for lifting the kidney margin and exposing the infundibulum in the sinus so that the incision can be extended into the calyx. This allows a bigger stone to be removed, especially if the stone extends into a calyx.

The stone can be removed using stone forceps (Turner-Warwick straight or curved stone forceps). Count the number of stones and compare the total with the number of stones observed on the x-ray film. Irrigate the renal pelvis with a red rubber Robinson catheter, and flush out any small fragments.

Coagulum pyelolithotomy

Coagulum pyelolithotomy is used when multiple small stones are present and are scattered throughout the calyceal system. Coagulum or a clot envelops the small stones, and fragments are removed with it.

Into the renal pelvis through a 19-gauge needle, inject cryoprecipitate and 1 mL methylene blue and inject 1 mL of thrombin and calcium chloride. Do not overdistend the renal pelvis.

Block the ureter with a noncrushing bulldog clamp. Thrombin and calcium chloride solution can be made by adding 5000 U of thrombin to 5 mL of saline and adding 10 mL of 10% calcium chloride. Another method to make coagulum is to inject the necessary volume of cryoprecipitate (ie, volume equal to that of the renal pelvis) and inject 1 mL of 10% calcium chloride. After 5-7 minutes, the clot is formed. The thromboplastin from the renal pelvis is used. Pyelolithotomy is then performed, and the clot, along with the stones, is removed.

The procedure is usually safe, but pulmonary embolism and hepatitis are possibilities. This procedure is rarely performed in the United States because of concerns about possible infectious agents in the materials used.

Avoid overdistension of the renal pelvis or ureter. Contact x-ray films can be used to localize the stone. A flexible nephroscope, rigid nephroscope, or cystoscope can be used, if needed, to inspect, locate, and retrieve a stone or fragment from a calyx. Intraoperative fluoroscopy or systematic inspection of each calyx with a flexible cystoscope can also be used to ensure stone-free status.

Pyelotomy may be closed with 4-0 chromic or 5-0 synthetic continuous suture. Try to create a watertight closure, but this is not essential. Insert a drain through a stab incision to drain the pyelotomy site. Close the wound in 2 layers, transversalis and internal oblique fascia, with 0-0 synthetic absorbable suture. Suture the external oblique fascia with interrupted sutures of the same material. Unflexing the table and lowering the kidney bridge help greatly in closing. Skin can be closed with 3-0 monofilament nylon mattress sutures or staples.

Laparoscopic pyelolithotomy

Laparoscopic pyelolithotomy has growing support, especially when laparoscopic reconstruction of a UPJ obstruction is planned 4.

The incisions are the same as used for a laparoscopic pyeloplasty. Upon incision of the renal pelvis, laparoscopic graspers alone can be used to assist in extricating the stone. Irrigation and use of a flexible cystoscope through the 10-mm or 12-mm port is also useful in more difficult extractions.

Pyelolithotomy complications

As with all renal stone procedures, a urinary tract infection or pyelonephritis may occur. Perinephric abscesses may require percutaneous drainage. Retained stone fragments, ureteral/renal pelvic scarring, and obstruction are possibilities that may require additional open or endoscopic urological surgery.

As with any surgery, atelectasis is the most common complication of stone surgery. Aggressive incentive spirometry and patient ambulation assist in treating this. Some advocate a brief period of hyperventilation with vigorous lung expansion immediately postoperatively while the patient is supine and just prior to extubation.

Flank hernia/laxity due to intercostal nerve injury and disruption of the fascial closure are usually benign but very bothersome to patients. An adequate cosmetic result is difficult with this repair. Stone formation on the sutures used to close the renal pelvis incision has been reported.

Other complications include urine leak or urinoma, urinary fistula (to skin or bowel), bleeding, arteriovenous malformations, pseudoaneurysms, and injury to pleura/lung with pneumothorax. The vast majority of cases with urinary leakage and fistula between the collecting system and skin can be treated with a ureteral stent; percutaneous placement of a perinephric drain may be needed if an intraoperative drain was not placed or has already been removed at the time the leak is recognized. An indwelling urethral catheter may also be needed to divert the flow from the fistula tract and allow it to seal.

A small pneumothorax without respiratory distress due to an iatrogenic pleural injury can usually be treated conservatively and monitored. Larger air pockets can be treated with aspiration or a chest tube. If a lung injury is also present, a chest tube should be the initial therapy.

Fistula with the bowel can sometimes be managed with a stent, urethral indwelling catheter, bowel rest, and parenteral nutrition. If the fistula does not respond to this conservative management, surgical repair and possible nephrectomy and/or bowel resection may be necessary.

Bleeding, arteriovenous malformations, and pseudoaneurysms can be severe problems that may require embolization, emergent surgical intervention, transfusion, possible loss of the kidney, and even loss of life in extreme cases.

Pyelolithotomy recovery

Pain is less severe if bupivacaine (Marcaine) is injected, but be absolutely sure that the bupivacaine is not accidentally injected into a vessel because it can cause cardiac arrhythmias.

Drains may be removed in 24 hours if the drainage is less than 25 mL. Ureteral stents can be removed after 2 weeks. If a ureteral catheter is used as a stent, it can be removed after 5 days.

Follow-up

Perform an imaging study to confirm the removal of all stone particles.

Pyelolithotomy prognosis

While the stone-free rates after pyelolithotomy are excellent for solitary renal pelvic stones, the morbidity is so much greater than even multiple percutaneous, ureteroscopic, and/or extracorporeal shockwave approaches that this procedure is rarely used. Urologists practicing before the advent of these technologies or in areas with little access to the complex instrumentation for noninvasive stone management have the most experience and best surgical results.

Note that these patients should be informed about kidney stone prevention metabolic analysis, including a 24-hour urine collection for calcium, citrate, oxalate, magnesium, phosphate, sodium, uric acid, and total volume analysis. Optimally, a screening blood test for hypercalcemia, hyperparathyroidism, and hyperuricemia should also be performed.

References- Pyelolithotomy. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/448503-overview

- Rui X, Hu H, Yu Y, Yu S, Zhang Z. Comparison of safety and efficacy of laparoscopic pyelolithotomy versus percutaneous nephrolithotomy in patients with large renal pelvic stones: a meta-analysis. J Investig Med. 2016 Aug. 64 (6):1134-42.

- Stein RJ, Turna B, Nguyen MM, Aron M, Hafron JM, Gill IS, et al. Laparoscopic pyeloplasty with concomitant pyelolithotomy: technique and outcomes. J Endourol. 2008 Jun. 22(6):1251-5.

- Haggag YM, Morsy G, Badr MM, Al Emam AB, Farid M, Etafy M. Comparative study of laparoscopic pyelolithotomy versus percutaneous nephrolithotomy in the management of large renal pelvic stones. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013 Mar-Apr. 7(3-4):E171-5.