What is Brown-Sequard syndrome

Brown-Sequard syndrome is a rare neurological condition caused by incomplete spinal cord injury which results after damage to one side of the spinal cord only (hemisection), typically in the neck (cervical spinal cord), or thoracic spinal cord, however, it could be anywhere along the length of the spinal cord 1. Brown-Sequard syndrome is characterized by a lesion in the spinal cord which results in weakness or paralysis (hemiparaplegia) on one side of the body and a loss of sensation (hemianesthesia) on the opposite side. Brown-Sequard syndrome may be caused by a spinal cord tumor, trauma (such as a puncture wound to the neck or back), ischemia (obstruction of a blood vessel), or infectious or inflammatory diseases such as tuberculosis (TB) or multiple sclerosis (MS). Estimates indicate among all traumatic causes, 4% of spinal cord injuries are Brown-Séquard syndrome 2.

Generally treatment for individuals with Brown-Sequard syndrome focuses on the underlying cause of the disorder. Early treatment with high-dose steroids may be beneficial in many cases. Other treatment is symptomatic and supportive.

Brown-Sequard syndrome causes

The most common causes of Brown- Séquard Syndrome can be divided into traumatic and non-traumatic injuries 1. Traumatic injuries are far more common. Gunshot wounds, stabbings, motor vehicle accident, blunt trauma or a fractured vertebra from a fall could be among the causes. To a lesser extent, Brown-Séquard Syndrome can result from a vast variety of non-traumatic causes including vertebral disc herniation, cysts, cervical spondylosis, tumors, multiple sclerosis, and cystic disease, radiation, decompression sickness. Other miscellaneous vascular reasons include hemorrhage or ischemia. There could be infectious causes like tuberculosis, transverse myelitis, herpes zoster, empyema, and meningitis 3.

Traumatic causes

Brown-Séquard syndrome can be caused by any mechanism resulting in damage to 1 side of the spinal cord. Multiple causes of Brown-Séquard syndrome have been described in the literature. The most common cause remains traumatic injury, often a penetrating mechanism, such as a stab or gunshot wound or a unilateral facet fracture and dislocation due to a motor vehicle accident or fall 4.

More unusual causes that have been reported include assault with a pen, removal of a cerebrospinal fluid drainage catheter after thoracic aortic surgery, and injury from a blowgun dart 5. Traumatic injury may also be the result of blunt trauma or pressure contusion.

Nontraumatic causes

Numerous nontraumatic causes of Brown-Séquard syndrome have also been reported, including the following:

- Tumor (primary or metastatic)

- Multiple sclerosis

- Disk herniation 6

- Cervical spondylosis

- Herniation of the spinal cord through a dural defect (idiopathic or posttraumatic)

- Epidural hematoma

- Vertebral artery dissection 7

- Transverse myelitis

- Radiation

- Type II decompression sickness

- Intravenous drug use

- Tuberculosis

- Ossification of the ligamentum flavum 8

- Meningitis

- Empyema

- Herpes zoster

- Herpes simplex

- Syphilis

- Ischemia

- Hemorrhage – Including spinal subdural/epidural and hematomyelia

- Chiropractic manipulation – Rare, but reported 9

A literature review by Gunasekaran et al found that out of 37 patients with cervical intradural disk herniation, a rare condition, 43.2% had Brown-Séquard syndrome, while 10.8% had Horner syndrome 10.

A retrospective study by Ronzi et al looked at patients with acute traumatic spinal cord injury associated with cervical spinal canal stenosis, in whom spinal stability was retained. The investigators determined that of the 78.6% of patients with a clinical syndrome, the greatest proportion had Brown-Séquard–plus syndrome (30.9% of patients) 11.

Brown Sequard syndrome pathophysiology

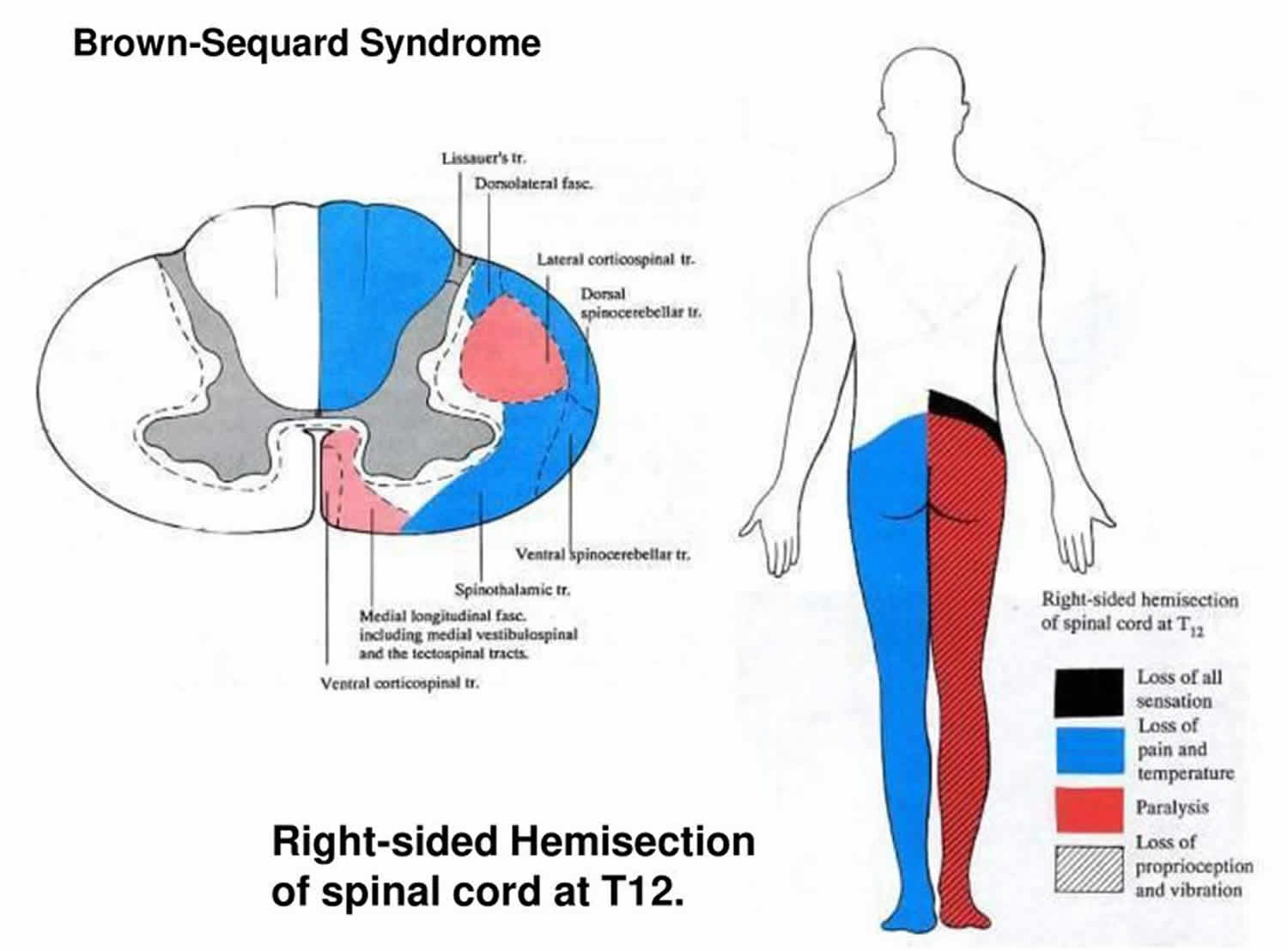

With Brown-Sequard syndrome, a clean-cut hemisection is usually not visible. However, partial hemisection is evident, and it often includes all the nerve tracts lying along the path in the injured area involved. If the lesion is involved in the cervical region, for example, C5 to T1, that hemisection would create deficits in the following manner:

All sensory sensations would be lost ipsilaterally.

- Dorsal columns: sensations which are responsible for fine touch, vibration, two-point discrimination, and conscious proprioception would be affected on the same side of lesion because dorsal columns ascend ipsilaterally carrying the information from the lower half of body in the gracile fasciculus and the upper half of body in the cuneate fasciculus before they decussate in lower medulla.

- Spinothalamic tracts which are responsible for pain, temperature, and crude touch would be affected contralateral to the lesion because they ascend a level up and then cross to the opposite side of the cord.

- Dorsal and ventral spinocerebellar tracts: carrying sensations of unconscious proprioception, lesion affecting dorsal spinocerebellar tracts cause ipsilateral dystaxia and involvement of ventral spinocerebellar would cause contralateral dystaxia since these fibers ascend and cross to the opposite side.

- Horner’s syndrome: if the lesion is at or above T1, this will cause ipsilateral loss of sympathetic fibers resulting in ptosis, miosis, and anhydrosis. There might also be redness of face due to vasodilation.

- Corticospinal tracts: there would be an ipsilateral loss of movements at the site of lesion which presents with flaccid paralysis, lower motor neuron lesion like loss of muscle mass, fasciculations, and decreased power and tone. Below the level of lesion, there would be upper motor neurons lesion signs like paralysis with hypertonia clasp knife type, hyperreflexia, and positive Babinski sign. There is no significant motor deficit on the contralateral side.

Brown-Sequard syndrome symptoms

Clinical history often reflects the cause of Brown-Séquard syndrome. Onset of symptoms may be acute or gradually progressive. Complaints are related to hemiparesis or hemiparalysis and sensory changes, paresthesias, or dysesthesias in the contralateral limb(s). Isolated weakness or sensory changes may be reported.

Complete hemisection, causing classic clinical features of pure Brown-Séquard syndrome, is rare. Incomplete hemisection causing Brown-Séquard syndrome plus other signs and symptoms is more common. These symptoms may consist of findings from posterior column involvement such as loss of vibratory sensation.

Brown Sequard syndrome complications

Untreated Brown-Sequard syndrome may bring complications like hypotension or spinal shock, depression, pulmonary embolism and infections most commonly in the lungs and urinary tract. Respiratory support is critical for patients with high thoracic and cervical lesions.

Brown-Sequard syndrome diagnosis

Diagnosis of Brown-Séquard Syndrome is made by neurological history, any trauma history, and physical examination. Laboratory investigations in case of infectious etiologies like purified protein derivative and sputum for acid-fast bacilli along with chest x-ray. MRI or X-ray when traumatic injuries are in suspected as well as neoplastic causes.

A detailed history and physical exam are extremely important to understand the extent of damage done and establishing what to expect in the coming days regarding neurological deficits. Accounts should have the details of any injury. Careful examination of the wound site is necessary because it may reveal an injury to the dorsal column systems, spinothalamic tracts, dorsal and ventral spinocerebellar tracts, corticospinal tracts and Horner’s syndrome (if the lesion is above or at the level of T1). If the wound is involving the lower lumbar region, then the bladder and bowel symptoms can be detected or respiratory symptoms if lesions are near the brain stem. Usually incomplete forms of the syndrome commonly occur, and this can be caused by vascular impairment secondary to compression of the cord, so history is necessary to rule out infectious causes or recent travel to the endemic areas should be ruled out.

A neurological examination should comprise of a detailed motor and sensory evaluation, although sometimes it is hard to perform the physical exam in the beginning especially after trauma because patients are in spinal shock. Clinically, there would be an ipsilateral sensory loss of all sensations, pressure, vibration, position and flaccid paralysis at the level of lesion and spastic paraparesis below the level of lesion; contralaterally there would be loss of pain and temperature.

Brown-Sequard syndrome treatment

The treatment for individuals with Brown-Sequard syndrome depends on the cause and is focused on preventing the complications. Use of steroids is controversial in traumatic spinal cord injuries due to the risk of infections, and they are not effective in case of Brown-Sequard syndrome, but standard perioperative prophylactic antibiotics are recommended. Decompression surgery is considered for patients who have a traumatic injury or any tumor or abscess causing cord compression 12.

Nonoperative treatment to support individuals, with an emphasis on less dependency for daily activities and improving quality of life with a multidisciplinary approach involving spinal cord injury physicians, nurses, occupational therapists, and social workers. Specific devices can help to improve the quality of life and daily activities for patients with Brown-Sequard syndrome such as wheelchairs, limb supports and hand splits. If the patient has difficulty in breathing or swallowing, various aids can be applied; cervical collars can also be used depending on the level of injury. In the case of thoracolumbar region involvement, spinal orthosis can be used.

Brown Sequard syndrome prognosis

The prognosis for individuals with Brown-Sequard syndrome varies depending on the cause of injury and the extent to which the spinal cord is damaged. Generally, as Brown-Sequard syndrome is an incomplete spinal cord injury the potential for significant recovery is strong. More than half of Brown-Sequard syndrome patients recover well, and the majority of post-traumatic patients recover motor function. Recovery becomes slower throughout three to six months, and it can take up to two years for ongoing neurological recovery 13. If the deficit is at the level where it affects bowel and bladder, patients may gain their function in 90% of the cases. Most patients will regain some strength in lower extremities, and most will regain functional walking ability. When motor function loss is present, recovery is faster on the contralateral side and slower on the ipsilateral side.

Prognosis for significant motor recovery in Brown-Séquard syndrome is good 14. One half to two thirds of the 1-year motor recovery occurs within the first 1-2 months following injury. Recovery then slows but continues for 3-6 months and has been documented to progress for up to 2 years following injury.

The most common pattern of recovery includes the following 15:

- Recovery of the ipsilateral proximal extensor muscles prior to that of the ipsilateral distal flexors

- Recovery from weakness in the extremity with sensory loss before recovery occurs in the opposite extremity

- Recovery of voluntary motor strength and a functional gait within 1-6 months

A retrospective review by Pollard and Apple of 412 patients with traumatic, incomplete cervical spinal cord injuries found that the most important prognostic variable relating to neurologic recovery was completeness of the lesion. If the cervical spinal cord lesion is incomplete, such as central cord or Brown-Séquard syndrome, younger patients with have a more favorable prognosis for recovery.

Recovery in the study was not linked to high-dose steroid administration, early surgical intervention on a routine basis, or surgical decompression in patients with stenosis who were without fracture. Other studies, however, have demonstrated improved outcomes for patients with traumatic spinal cord injuries who were given high-dose steroids early in the clinical course 16. Surgical treatment of stenosis with myelopathy or incomplete spinal cord injury, including Brown-Séquard syndrome, has been shown to halt progressive loss of neurological function 17.

Studies suggest that spared descending motor axons in the contralateral cord may mediate much of the motor recovery. Most individuals with incomplete injuries at the time of initial examination recover the ability to ambulate.

Morbidity and mortality

Potential long-term complications of Brown-Séquard syndrome are similar to those associated with aging and spinal cord injury. Lower extremity problems related to ambulation may increase, but this phenomenon has not been documented in the literature.

Acute mortality rates are measured for all traumatic spinal cord injuries without differentiation according to level or completeness. These figures do not include nontraumatic cases and do not differentiate the incomplete spinal cord syndromes.

Incomplete tetraplegia at hospital discharge has been the most frequent neurologic category (40.6% of traumatic spinal cord injuries) reported to the National Spinal Cord Injury Database since 2010. There are no data specific to Brown-Séquard syndrome.

The mortality rate for incomplete tetraplegia in general is 5.7% during the initial hospitalization if no surgery is performed and is 2.7% if surgical intervention is performed. Mortality prior to hospitalization is not known but has decreased with the advancement of emergency medical services.

Morbidity following any spinal cord injury, regardless of etiology, is related to loss of motor, sensory, and autonomic function, as well as to common secondary medical complications. Although prognosis for neurologic recovery is better in the incomplete syndromes than it is in complete spinal cord injuries, complete recovery by the time of hospital discharge is less than 1%. The most prevalent medical complication is pressure ulcer, followed by pneumonia, urinary tract infection, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolus, and postoperative infection.

References- Shams S, Arain A. Brown Sequard Syndrome. [Updated 2019 Jun 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538135

- Halvorsen A, Pettersen AL, Nilsen SM, Halle KK, Schaanning EE, Rekand T. Epidemiology of traumatic spinal cord injury in Norway in 2012-2016: a registry-based cross-sectional study. Spinal Cord. 2019 Apr;57(4):331-338.

- Kashyap S, Majeed G, Lawandy S. A rare case of Brown-Sequard syndrome caused by traumatic cervical epidural hematoma. Surg Neurol Int. 2018;9:213.

- Mac-Thiong JM, Parent S, Poitras B, Joncas J, Labelle H. Neurological Outcome and Management of Pedicle Screws Misplaced Totally Within the Spinal Canal. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2012 Jul 18.

- Moin H, Khalili HA. Brown Séquard syndrome due to cervical pen assault. J Clin Forensic Med. 2006 Apr. 13(3):144-5.

- Urrutia J, Fadic R. Cervical disc herniation producing acute Brown-Sequard syndrome: dynamic changes documented by intraoperative neuromonitoring. Eur Spine J. 2012 Jun. 21 Suppl 4:S418-21.

- Ginos J, Mcnally S, Cortez M, Quigley E, Shah LM. Vertebral Artery Dissection and Cord Infarction – an Uncommon Cause of Brown-Séquard and Horner Syndromes. Cureus. 2015 Aug 21. 7 (8):e308.

- Chen PY, Lin CY, Tzaan WC, et al. Brown-Sequard syndrome caused by ossification of the ligamentum flavum. J Clin Neurosci. 2007 Sep. 14(9):887-90.

- Domenicucci M, Ramieri A, Salvati M, Brogna C, Raco A. Cervicothoracic epidural hematoma after chiropractic spinal manipulation therapy. Case report and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Spine. 2007 Nov. 7(5):571-4.

- Gunasekaran A, de Los Reyes NKM, Walters J, Kazemi N. Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Surgical Treatment of Spontaneous Cervical Intradural Disc Herniations: A Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2018 Jan. 109:275-84.

- Ronzi Y, Perrouin-Verbe B, Hamel O, Gross R. Spinal cord injury associated with cervical spinal canal stenosis: outcomes and prognostic factors. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2018 Jan. 61 (1):27-32.

- Lee DY, Park YJ, Song SY, Hwang SC, Kim KT, Kim DH. The Importance of Early Surgical Decompression for Acute Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury. Clin Orthop Surg. 2018 Dec;10(4):448-454.

- Wirz M, Zörner B, Rupp R, Dietz V. Outcome after incomplete spinal cord injury: central cord versus Brown-Sequard syndrome. Spinal Cord. 2010 May;48(5):407-14.

- McKinley W, Santos K, Meade M, et al. Incidence and outcomes of spinal cord injury clinical syndromes. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007. 30(3):215-24.

- Little JW, Halar E. Temporal course of motor recovery after Brown-Sequard spinal cord injuries. Paraplegia. 1985 Feb. 23(1):39-46.

- Pollard ME, Apple DF. Factors associated with improved neurologic outcomes in patients with incomplete tetraplegia. Spine. 2003 Jan 1. 28(1):33-9.

- Kohno M, Takahashi H, Yamakawa K, et al. Postoperative prognosis of Brown-Séquard-type myelopathy in patients with cervical lesions. Surg Neurol. 1999 Mar. 51(3):241-6.