What is carcinoma in situ

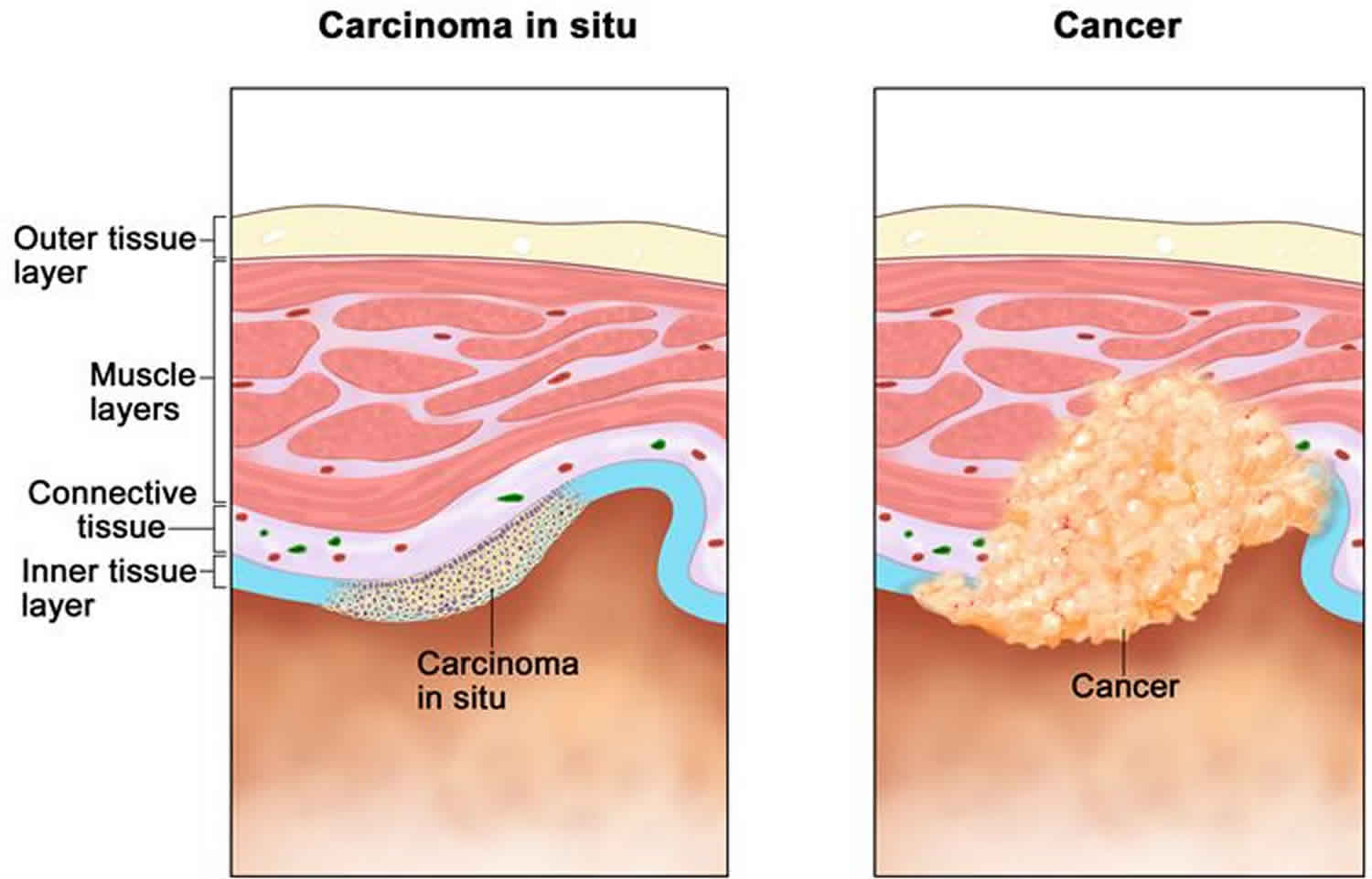

Carcinoma in-situ is defined as a group of abnormal cells that remain in the place where they first formed.

Squamous cell carcinoma in situ

Squamous cell carcinoma in-situ is also called intraepidermal squamous cell carcinoma, Bowen’s disease or intraepidermal carcinoma, which is a common superficial form of skin cancer.

Squamous cell carcinoma in-situ is derived from squamous cells, the flat epidermal cells that make keratin—the horny protein that makes up skin, hair and nails. ‘Intraepidermal’ and ‘in situ’ mean the malignant cells are confined to cell of origin, that is, the epidermis.

Invasive squamous cell carcinoma arises in about 5% of squamous cell carcinoma in-situ lesions.

What are the clinical features of squamous cell carcinoma in-situ?

Squamous cell carcinoma in-situ presents as one or more irregular scaly plaques of up to several centimeters in diameter. They are most often red but may also be pigmented.

Although squamous cell carcinoma in-situ may arise on any area of skin, it is most often diagnosed on sun-exposed sites of the ears, face, hands and lower legs. When there are multiple plaques, distribution is not symmetrical (unlike psoriasis).

Squamous cell carcinoma in-situ may start to grow under a nail, when it results in a red streak (erythronychia) that later may destroy the nail plate.

Figure 1. Squamous cell carcinoma in-situ

Who gets squamous cell carcinoma in-situ?

Risk factors for squamous cell carcinoma in-situ include:

- Sun exposure: Squamous cell carcinoma in-situ is most often found in sun damaged individuals.

- Arsenic ingestion: Squamous cell carcinoma in-situ is common in populations exposed to arsenic.

- Ionizing radiation: Squamous cell carcinoma in-situ was common on unprotected hands of radiologists early in the 20th century.

- Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection: this is implicated in squamous cell carcinoma in-situ on fingers and fingernails.

- Immune suppression due to disease (e.g. chronic lymphocytic leukemia) or medicines (eg azathioprine, ciclosporin).

Up to 50% of patients with squamous cell carcinoma in-situ have other keratinocytic skin cancers, mainly basal cell carcinoma.

What causes squamous cell carcinoma in-situ?

Ultraviolet radiation (UV) is the main cause of squamous cell carcinoma in-situ. It damages the skin cell nucleic acids (DNA), resulting in a mutant clone of the gene p53. This sets off uncontrolled growth of the skin cells. UV also suppresses the immune response, preventing recovery from damage.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is another major cause of squamous cell carcinoma in-situ. Oncogenic strains of HPV are the main cause of squamous intraepithelial lesions (SIL), that is, squamous cell carcinoma in situ in mucosal tissue.

How can squamous cell carcinoma in-situ be prevented?

Very careful sun protection at any time of life can reduce the number of squamous cell carcinomas in-situ. This is particularly important for ageing, sun-damaged white skin; and in patients that are immune suppressed by disease, for example with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, or by medications.

- Stay indoors or under the shade in the middle of the day.

- Wear covering clothing.

- Apply high protection SPF50+, broad-spectrum sunscreens generously to exposed skin if outdoors.

- Avoid indoor tanning (sun beds and solaria).

How is squamous cell carcinomas in-situ diagnosed?

Squamous cell carcinomas in-situ is often recognized clinically. Dermatoscopy of a red scaly irregular plaque is supportive if it reveals crops of rounded and/or coiled blood vessels.

Diagnosis may be confirmed by biopsy; histology reveals full thickness dysplasia of the epidermis.

Squamous cell carcinomas in-situ treatment

As squamous cell carcinoma in-situ is confined to the surface of the skin, there are various ways to remove it. Recurrence rates are high, whatever method is used, particularly in immune suppressed patients.

Observation

As the risk of invasive squamous cell carcinoma is low, it may not be necessary to remove all lesions particularly in elderly patients. Keratolytic emollients, e.g., containing urea or salicylic acid, may be sufficient to improve symptoms.

Excision

Solitary lesions can be cut out, and the defect repaired by stitching it up. Excision is often recommended if there is suspicion of invasive squamous cell carcinoma.

Superficial skin surgery

Superficial skin surgery refers to shave, curettage and electrosurgery, and is a good choice for solitary or few hyperkeratotic lesions. The lesion is sliced off or scraped out, then the base is cauterized. Dressings are applied to the open wound to encourage moist wound healing over the next few weeks.

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy means removing a lesion by freezing it, usually with liquid nitrogen. Moderately aggressive cryotherapy is suitable for multiple, small, flat patches of squamous cell carcinomas in-situ. It leaves a permanent white mark at the site of treatment.

Fluorouracil cream

5-fluorouracil cream contains a cytotoxic agent and can be applied to multiple lesions. The cream may be applied to squamous cell carcinomas in-situ for 4 weeks, and repeated if necessary. It causes a vigorous skin reaction that may ulcerate.

Imiquimod cream

Imiquimod cream is an immune response modifier used off-licence to treat squamous cell carcinomas in-situ. It is applied 3–5 times weekly for 4–16 weeks and causes an inflammatory reaction.

Photodynamic therapy

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) refers to treatment with a photosensitizer (a porphyrin chemical) that is applied to the affected area prior to exposing it to a strong source of visible light. The treated area develops an inflammatory reaction and then heals over a couple of weeks or so. The best studied, methyl levulinate cream photodynamic therapy used off licence, provides high cure rates for squamous cell carcinomas in-situ on the face or lower legs, with excellent cosmetic results. The main disadvantage is the pain experienced by many patients during treatment.

Other treatments

Other treatments occasionally used in the treatment of squamous cell carcinomas in-situ include:

- Combination treatments

- Diclofenac gel

- Topical retinoid (tazarotene, tretinoin)

- Chemical peel

- Radiotherapy

- Electron beam therapy

- Carbon dioxide laser ablation

- Erbium:YAG laser ablation

- Oral retinoid (acitretin, isotretinoin)

Squamous cell carcinoma in-situ prognosis

Squamous cell carcinomas in-situ may recur months or years after treatment. The same treatment can be repeated or another method used.

Patients that have been treated for squamous cell carcinomas in-situ are at risk of developing new lesions of squamous cell carcinomas in-situ. They are also at increased risk of other skin cancers, especially squamous cell carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma and melanoma.

Carcinoma in situ of breast

When your breast was biopsied, the samples taken were studied under the microscope by a specialized doctor with many years of training called a pathologist. The pathologist sends your doctor a report that gives a diagnosis for each sample taken. Carcinoma in-situ of the breast is used for the earliest stage of breast cancer, when it is confined to the layer of cells where it began. The normal breast is made of tiny tubes (ducts) that end in a group of sacs (lobules). Cancer starts in the cells lining the ducts or lobules, when a normal cell becomes a carcinoma cell. As long as the carcinoma cells are still confined to the breast ducts or lobules, and do not break out and grow into surrounding tissue, it is considered in-situ carcinoma (also known as carcinoma in-situ or CIS).

About 1 in 5 new breast cancers will be ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS). Nearly all women with this early stage of breast cancer can be cured.

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), is also called intraductal carcinoma and Stage 0 breast cancer. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is a non-invasive or pre-invasive breast cancer. This means the cells that line the ducts have changed to cancer cells but they have not spread through the walls of the ducts into the nearby breast tissue.

Because ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) hasn’t spread into the breast tissue around it, it can’t spread (metastasize) beyond the breast to other parts of the body.

Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is considered a pre-cancer because sometimes it can become an invasive cancer. This means that over time, ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) may spread out of the duct into nearby tissue, and could metastasize (spread). Right now, though, there’s no good way to know for sure which will become invasive cancer and which ones won’t. So almost all women with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) will be treated.

Once the carcinoma cells have grown and broken out of the ducts or lobules, it is called invasive or infiltrating carcinoma. In an invasive carcinoma, the tumor cells can spread (metastasize) to other parts of your body.

There are 2 main types of carcinoma in-situ of the breast:

- Ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS). Intraductal carcinoma is another name for ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS).

- Lobular carcinoma in-situ (LCIS).

Sometimes ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) and lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) are both found in the same biopsy.

In-situ carcinoma with duct and lobular features means that the in-situ carcinoma looks like ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) in some ways and lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS) in some ways (when looked at under the microscope), and so the pathologist can’t call it one or the other.

These are all different ways of describing how the ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) looks under the microscope:

- Ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) that is high grade, is nuclear grade 3, or has a high mitotic rate is more likely to come back (recur) after it is removed with surgery.

- Ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) that is low grade, is nuclear grade 1, or has a low mitotic rate is less likely to come back after surgery.

- Ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) that is intermediate grade, is nuclear grade 2, or has an intermediate mitotic rate falls in between these two.

Patients with higher grade ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) may need additional treatment.

Figure 2. Ductal carcinoma in situ

Ductal carcinoma in situ causes

It’s not clear what causes ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS). Ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) forms when genetic mutations occur in the DNA of breast duct cells. The genetic mutations cause the cells to appear abnormal, but the cells don’t yet have the ability to break out of the breast duct.

Researchers don’t know exactly what triggers the abnormal cell growth that leads to ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS). Factors that may play a part include your lifestyle, your environment and genes passed to you from your parents.

Risk factors for ductal carcinoma in-situ

Factors that may increase your risk of ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) include:

- Increasing age

- Personal history of benign breast disease, such as atypical hyperplasia

- Family history of breast cancer

- Never having been pregnant

- Having your first baby after age 30

- Having your first period before age 12

- Beginning menopause after age 55

- Genetic mutations that increase the risk of breast cancer, such as those in the breast cancer genes BRCA1 and BRCA2

Ductal carcinoma in situ symptoms

Ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) doesn’t typically have any signs or symptoms. However, ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) can sometimes cause signs such as:

- A breast lump

- Bloody nipple discharge

Ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) is usually found on a mammogram and appears as small clusters of calcifications that have irregular shapes and sizes.

Ductal carcinoma in situ diagnosis

Breast imaging

Ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) is most often discovered during a mammogram used to screen for breast cancer. If your mammogram shows suspicious areas such as bright white specks (microcalcifications) that are in a cluster and have irregular shapes or sizes, your radiologist likely will recommend additional breast imaging.

You may have a diagnostic mammogram, which takes views at higher magnification from more angles. This examination evaluates both breasts and takes a closer look at the microcalcifications to be able to determine whether they are a cause for concern.

If the area of concern needs further evaluation, the next step may be an ultrasound and a breast biopsy.

Removing breast tissue samples for testing

During a core needle biopsy, a radiologist or surgeon uses a hollow needle to remove tissue samples from the suspicious area, sometimes guided by ultrasound (ultrasound-guided breast biopsy) or by X-ray (stereotactic breast biopsy). The tissue samples are sent to a lab for analysis.

In a lab, a doctor who specializes in analyzing blood and body tissue (pathologist) will examine the samples to determine whether abnormal cells are present and if so, how aggressive those abnormal cells appear to be.

Ductal carcinoma in situ treatment

Most women with ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) are cured with proper treatment. Treatment may include:

- Lumpectomy. This is a type of breast-conserving surgery (also called breast-sparing surgery). This may be followed by radiation therapy.

- Mastectomy. This is surgery to remove the breast or as much of the breast tissue as possible.

- Tamoxifen. This drug may also be taken to lower the chance that ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) will come back after treatment or to prevent invasive breast cancer.

Surgery

If you’re diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS), one of the first decisions you’ll have to make is whether to treat the condition with lumpectomy or mastectomy.

Lumpectomy

Lumpectomy is surgery to remove the area of ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) and a margin of healthy tissue that surrounds it. This is also known as a surgical biopsy or wide local incision. The procedure allows you to keep as much of your breast as possible, and depending on the amount of tissue removed, usually eliminates the need for breast reconstruction.

Research suggests that women treated with lumpectomy have a slightly higher risk of recurrence than women who undergo mastectomy; however, survival rates between the two groups are very similar.

If you have other serious health conditions, you might consider other options, such as lumpectomy plus hormone therapy, lumpectomy alone or no treatment.

Mastectomy

Mastectomy is an operation to remove all of the breast tissue. Breast reconstruction to restore the appearance of you breast can be done at the same time or in a later procedure, if you desire.

Most women with ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) are candidates for lumpectomy. However, mastectomy may be recommended if:

- You have a large area of ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS). If the area is large relative to the size of your breast, a lumpectomy may not produce acceptable cosmetic results.

- There’s more than one area of ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) (multifocal or multicentric disease). It’s difficult to remove multiple areas of ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) with a lumpectomy. This is especially true if ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) is found in different sections — or quadrants — of the breast.

- Tissue samples taken for biopsy show abnormal cells at or near the edge (margin) of the tissue specimen. There may be more ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) than originally thought, meaning that a lumpectomy might not be adequate to remove all areas of ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS). Additional tissue may need to be removed, which could require mastectomy to remove all of the breast tissue if the area of ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) involvement is large relative to the size of the breast.

- You’re not a candidate for radiation therapy. Radiation is usually given after a lumpectomy. You may not be a candidate if you’re diagnosed in the first trimester of pregnancy, you’ve received prior radiation to your chest or breast, or you have a condition that makes you more sensitive to the side effects of radiation therapy, such as systemic lupus erythematosus.

- You prefer to have a mastectomy rather than a lumpectomy. For instance, you might not want a lumpectomy if you don’t want to have radiation therapy.

Because ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) is noninvasive, surgery typically doesn’t involve the removal of lymph nodes from under your arm. The chance of finding cancer in the lymph nodes is extremely small.

If tissue obtained during surgery leads your doctor to think that abnormal cells may have spread outside the breast duct or if you are having a mastectomy, then a sentinel node biopsy or removal of some lymph nodes may be done as part of the surgery.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy uses high-energy beams, such as X-rays or protons, to kill abnormal cells. Radiation therapy after lumpectomy reduces the chance that ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) will come back (recur) or that it will progress to invasive cancer.

Radiation most often comes from a machine that moves around your body, precisely aiming the beams of radiation at points on your body (external beam radiation). Less commonly, radiation comes from a device temporarily placed inside your breast tissue (brachytherapy).

Radiation is typically used after lumpectomy. But it might not be necessary if you have only a small area of ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) that is considered low grade and was completely removed during surgery.

Hormone therapy

Hormone therapy is a treatment to block hormones from reaching cancer cells and is only effective against cancers that grow in response to hormones (hormone receptor positive breast cancer).

Hormone therapy isn’t a treatment for ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) in and of itself, but it can be considered an additional (adjuvant) therapy given after surgery or radiation in an attempt to decrease your chance of developing a recurrence of ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) or invasive breast cancer in either breast in the future.

The drug tamoxifen blocks the action of estrogen — a hormone that fuels some breast cancer cells and promotes tumor growth — to reduce your risk of developing invasive breast cancer. It can be used for up to five years both in women who haven’t yet undergone menopause (premenopausal) and in those who have (postmenopausal).

Postmenopausal women may also consider hormone therapy with drugs called aromatase inhibitors. These medications, which are taken for up to five years, work by reducing the amount of estrogen produced in your body.

If you choose to have a mastectomy, there’s less reason to use hormone therapy.

With a mastectomy, the risk of invasive breast cancer or recurrent ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS) in the small amount of remaining breast tissue is very small. Any potential benefit from hormone therapy would apply only to the opposite breast.

Discuss the pros and cons of hormone therapy with your doctor.

Clinical trials

Clinical trials are studying new strategies for managing ductal carcinoma in-situ (DCIS), such as close monitoring rather than surgery after diagnosis. Whether you’re eligible to participate in a clinical trial depends on your specific situation. Talk with your doctor about your options.

Carcinoma in situ bladder

Carcinoma in situ bladder cancer (Stage 0is) is a flat, non-invasive carcinoma, also known as flat carcinoma in situ (CIS). Carcinoma in situ bladder cancer is growing in the inner lining layer of the bladder only. It has not grown inward toward the hollow part of the bladder, nor has it invaded the connective tissue or muscle of the bladder wall. Carcinoma in situ bladder cancer has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or distant sites (M0).

Carcinoma in situ bladder cancer usually appear as small grape like growths (also called papillary) that grow toward the center of the bladder without growing into the deeper bladder layers. Your surgeon may remove these growths using a method called transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT).

Transurethral resection of bladder tumor (TURBT) also known as just a transurethral resection (TUR), is the surgical removal (resection) of bladder tumors. This procedure is both diagnostic and therapeutic. It is diagnostic because the surgeon removes the tumor and all additional tissue necessary for examination under a microscope (histological assessment). TURBT is also therapeutic because complete removal of all visible tumors is the treatment for this cancer. Complete and correct TURBT is essential for good prognosis. In some cases, a second surgery is required after several weeks.

Figure 3. Carcinoma in situ bladder (Stage 0is (also called carcinoma in situ) is a flat tumor on the tissue lining the inside of the bladder)

Carcinoma in situ bladder symptoms

Bladder cancer signs and symptoms may include:

- Blood in urine (hematuria)

- Painful urination

- Pelvic pain

If you have hematuria, your urine may appear bright red or cola colored. Sometimes, urine may not look any different, but blood in urine may be detected during a microscopic exam of the urine.

People with bladder cancer might also experience:

- Back pain

- Frequent urination

But, these symptoms often occur because of something other than bladder cancer.

Carcinoma in situ cervix

In carcinoma in situ cervix (Stage 0) is also called cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN 3) or high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL), the full thickness of the lining covering the cervix has abnormal cells. These abnormal cells may become cancer and spread into nearby normal tissue.

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN 3) is defined by nuclear pleomorphism involving the full thickness of the squamous epithelium with mitotic activity at all levels. Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN 3) and severe dysplasia equates to carcinoma in situ (CIS), which term is seldom used nowadays.

Risk of progression is highest for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN 3) and inter-observer variation is considerably less than for CIN1 or CIN2 1. Microinvasive carcinoma is almost always seen in a background of widespread CIN3 further demonstrating its malignant potential. The exact risk is difficult to calculate because most cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN 3)/carcinoma in situ is treated when diagnosed.

Treatment of carcinoma in situ cervix (stage 0) or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN 3) may include the following:

- Conization, such as cold-knife conization, loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), or laser surgery.

- Hysterectomy for women who cannot or no longer want to have children. This is done only if the tumor cannot be completely removed by conization.

- Internal radiation therapy for women who cannot have surgery.

Figure 4. Carcinoma in situ cervix

Carcinoma in situ cervix symptoms

Women with early cervical cancers and carcinoma in situ cervix usually have no symptoms. Symptoms often do not begin until the cervical cancer becomes invasive and grows into nearby tissue. When this happens, the most common symptoms are:

- Abnormal vaginal bleeding, such as bleeding after vaginal sex, bleeding after menopause, bleeding and spotting between periods, and having (menstrual) periods that are longer or heavier than usual. Bleeding after douching or after a pelvic exam may also occur.

- An unusual discharge from the vagina − the discharge may contain some blood and may occur between your periods or after menopause.

- Pain during sex.

These signs and symptoms can also be caused by conditions other than cervical cancer. For example, an infection can cause pain or bleeding. Still, if you have any of these symptoms, see a health care professional right away. Ignoring symptoms may allow the cancer to grow to a more advanced stage and lower your chance for effective treatment.

The American Cancer Society recommends that women follow these guidelines to help find cervical cancer early. Following these guidelines can also find pre-cancers, which can be treated to keep cervical cancer from forming.

- All women should begin cervical cancer testing (screening) at age 21. Women aged 21 to 29, should have a Pap test every 3 years. HPV testing should not be used for screening in this age group (it may be used as a part of follow-up for an abnormal Pap test).

- Beginning at age 30, the preferred way to screen is with a Pap test combined with an HPV test every 5 years. This is called co-testing and should continue until age 65.

- Another reasonable option for women 30 to 65 is to get tested every 3 years with just the Pap test.

- Women who are at high risk of cervical cancer because of a suppressed immune system (for example from HIV infection, organ transplant, or long-term steroid use) or because they were exposed to DES in utero may need to be screened more often. They should follow the recommendations of their health care team.

- Women over 65 years of age who have had regular screening in the previous 10 years should stop cervical cancer screening as long as they haven’t had any serious pre-cancers (like CIN2 or CIN3) found in the last 20 years. Women with a history of CIN2 or CIN3 should continue to have testing for at least 20 years after the abnormality was found.

- Women who have had a total hysterectomy (removal of the uterus and cervix) should stop screening (such as Pap tests and HPV tests), unless the hysterectomy was done as a treatment for cervical pre-cancer (or cancer). Women who have had a hysterectomy without removal of the cervix (called a supra-cervical hysterectomy) should continue cervical cancer screening according to the guidelines above.

- Women of any age should NOT be screened every year by any screening method.

- Women who have been vaccinated against HPV should still follow these guidelines.

Some women believe that they can stop cervical cancer screening once they have stopped having children. This is not true. They should continue to follow American Cancer Society guidelines.

Although annual (every year) screening should not be done, women who have abnormal screening results may need to have a follow-up Pap test (sometimes with a HPV test) done in 6 months or a year.

The American Cancer Society guidelines for early detection of cervical cancer do not apply to women who have been diagnosed with cervical cancer, cervical pre-cancer, or HIV infection. These women should have follow-up testing and cervical cancer screening as recommended by their health care team.

References