Cicatricial pemphigoid

Cicatricial pemphigoid is a rare, chronic autoimmune blistering disorder which can produce scarring 1. Cicatricial pemphigoid can affect the skin only, mucous membranes only or both the skin and mucous membranes. When only mucous membranes are involved, the disease is often referred to as mucous membrane pemphigoid. When only the ocular membranes are involved, it may be referred to as ocular pemphigoid. Risk of scarring depends on the location of disease activity. Initial diagnosis can be a challenge. Due to the risks of serious complications, such as blindness and airway compromise, early and aggressive treatment initiation may be warranted.

Cicatricial pemphigoid is an antibody-mediated blistering disorder. The antibodies target molecules responsible for adhesion within the basement membrane zone of the mucosa and/or skin. This disrupts the normal structure and function of the basement membrane, which allows for the epidermis to separate from the dermis. Clinically, this manifests as blisters and erosions. Several target molecules are associated with the pathogenesis of cicatricial pemphigoid.

Cicatricial pemphigoid is a rare disorder 1. The exact prevalence and incidence are not known. The incidence of cicatricial pemphigoid estimated in a French study was 1.16 per million per year 2. The incidence of cicatricial pemphigoid estimated in German study was 0.87 per million per year 3.

In a study out of Greece, the mean age of onset for cicatricial pemphigoid was found to be 66 years of age, and there was a 1.5:1 female predominance 4. Female to male ratio for cicatricial pemphigoid was reported as high as 7:1 in a German population 3.

In a recent retrospective chart review of 162 patients with mucous membrane pemphigoid, 67% percent of patients had ocular involvement at presentation. In those without ocular involvement initially, it was estimated that the risk of developing ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid was 0.014 per person-year 5.

HLA-DQB1*0301 is a disease susceptibility marker for cicatricial pemphigoid 6.

Cicatricial pemphigoid causes

Autoantibodies targeted to components of the basement membrane zone have been identified as pathogenic in cicatricial pemphigoid 1. Patients with cicatricial pemphigoid may have antibodies detected to 180-kD bullous pemphigoid antigen (BP180) 7, laminin 332 (previously known as epiligrin or laminin-5) 8, beta-4-integrin 9 and other antigens that are not fully described.

Laminin 332 is a transmembrane protein that connects alpha-6-beta-4 integrin of the hemidesmosome of the keratinocyte to the non-collagenous 1 (NC1) domain of collagen VII. Collagen VII is the attachment for the anchoring fibrils that secure the basement membrane to the dermis. Laminin 332 assists in strengthening the attachment of the epidermis to the dermis from shearing forces.

BP180 is a transmembrane collagen, also referred to as collagen XVII. It is a component of the hemidesmosome of the epithelial cell. The dense plaque of the hemidesmosome binds keratin 5 and keratin 14 within the keratinocyte. BP180 spans the lamina lucida. The non-collagenous portion of the domain (N-terminus) is located near the cellular membrane and the collagenous portion of the domain (C-terminus) spans the lamina lucida and projects into the lamina densa. Sera from patients with bullous pemphigoid mainly target the N-terminus of BP180 whereas sera from cicatricial pemphigoid patients target the C-terminus. The variability in the target may explain the clinical differences seen among bullous pemphigoid and cicatricial pemphigoid patients 10. The target of the N-terminus would result in a more superficial blister, unlikely to scar, as seen in bullous pemphigoid. The target of the C-terminus would a result in a deeper separation, which would be more likely to scar, as seen in cicatricial pemphigoid 11.

Alpha-6-beta-4 integrin is a component of the hemidesmosome that binds the transmembrane laminin 332 which attaches to collagen VII. Sera and IgG fractions from patients with cicatricial pemphigoid have been shown to target the intracellular portion of alpha-6-beta-4 integrin suggesting that this may have a pathogenic role in cicatricial pemphigoid 12. A recent study demonstrated that sera from patients with ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid reacted to beta-4 integrin 13.

Cicatricial pemphigoid symptoms

The mouth is the most common location for involvement with cicatricial pemphigoid. It may be the only site affected. All areas of the oral cavity may be involved including the buccal mucosa, gingiva, tongue, vermillion lips, and palate 14. The disease may extend to posterior pharynx. Clinical appearance includes desquamative gingivitis, blisters, erosions, and ulcers. Patients with desquamative gingivitis may experience pain or bleeding when brushing teeth. Long-term inflammation and difficulty in maintaining oral hygiene may lead to caries and loss of teeth and alveolar bone 15. Scarring is uncommon but may present as white reticulated patches or adhesions 15.

Cicatricial pemphigoid of the ocular mucosa is often progressive. Scar formation can result in blindness. Inflammation may be slowly progressive. The patient may experience non-specific symptoms of eye irritation, such as burning or excessive tearing 8. The disease may present in one eye only; however, over the course of a couple of years, the disease typically affects both eyes 10. Rarely, patients present with frank blisters. Early scarring is first noted in the inferior fornices. Symblepharons are fibrous strands connecting the conjunctiva of the lid to the globe. These are best visualized when pulling down on the lower eyelid and having the patient look up 10. The endstage of this process results in scarring of the entire conjunctival sack, known as ankyloblepharon 10. This results in the inability for the lid to close completely 10. The chronic inflammation of the conjunctiva also leads to fibrosis of the lacrimal glands and goblet cells, resulting in decreased tear and mucin production. Scarring of the lid results in entropion (inward turning of the lid) and trichiasis (in-turning of the eyelashes) 10. The combination of abrasion of the cornea by entropion and trichiasis, decreased tear production and mucin production, and loss of lid closure function results in keratinization of the corneal epithelium 10. This ultimately results in decreased visual acuity 10.

Nasopharyngeal involvement is less common. It may present as crusted nasal lesions, epistasis, or chronic sinusitis 16. Adhesions and scarring can occur between structures, leading to airway obstruction.[17]. This has been reported to result in sleep apnea 16. Laryngeal involvement may present as a sore throat or hoarseness.[17] If scarring occurs, then the loss of phonation becomes permanent 16. Tracheostomy has been reported as a necessary life-saving intervention in patients with the severe disease resulting in airway compromise 12.

Esophageal involvement may present as pain, dysphagia, odynophagia, and stenosis 16.

Cicatricial pemphigoid of the genital and anal mucosa is rare. Erosions and ulcerations can lead to considerable discomfort of the genital skin. Scarring can lead to narrowing of the urethra and vaginal opening. Stenosis of these structures may require surgical intervention to restore function 13. The most common symptoms of anal involvement are pain and spasm 13.

Cutaneous lesions of cicatricial pemphigoid occur in two clinical presentations. The first subtype presents as a more generalized eruption of tense bullae without scarring. The second subtype presents as blisters on an erythematous base occurring in localized areas, resulting in atrophic scarring. This most commonly affects the head and neck area. Activity in the scalp often leads to alopecia 11. Brunsting-Perry pemphigoid, which was once thought to be a form of cicatricial pemphigoid, presents as a scarring bullous eruption of the head and neck skin without mucous membrane involvement. This is now believed to be a phenotype of epidermolysis bullosa acquisita.

Cicatricial pemphigoid complications

Oral mucosal complications include painful scarring lesions and adhesion formation causing limitation in movement.

Gingival complications include caries, loss of gingival tissue, and alveolar bone and tooth loss.

Ocular complications include irritation, decreased tear and mucin production, secondary infection, symblepharons, ankyloblepharons, corneal irritation, corneal neovascularization, corneal ulcers, and blindness.

Nasal complications include discharge, epistaxis, crust formation, chronic sinusitis, scarring, and impaired air flow.

Pharyngeal complications include hoarseness, loss of voice, supraglottic stenosis, and airway compromise.

Esophageal complications include dysphagia, odynophagia, aspiration, and stricture formation.

Anogenital complications include painful ulcerations, stenosis, and stricture formation.

Cicatricial pemphigoid diagnosis

Biopsy of lesional skin for histopathology is recommended.

Biopsy of perilesional skin for direct immunofluorescence is recommended. Direct immunofluorescence typically demonstrates IgG and C3 as a linear band at the basement membrane zone 17. Linear deposition of IgA at the basement membrane zone is occasionally seen 18. To increase sensitivity, multiple and repeated sampling may be warranted 19.

Indirect immunofluorescence is recommended; however, it is only positive in a small percentage of patients. The titer is usually low 17. Indirect immunofluorescence on the salt-split skin may show an epidermal or dermal pattern. Indirect immunofluorescence shows the presence of IgG or IgA autoantibodies. To increase the diagnostic utility of the indirect immunofluorescence, it has been recommended to perform with a concentrated assay, using salt-split skin study, and evaluate for both the presence of IgG and IgA 11.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing for the presence of anti-BP180 C terminal domain and anti-laminin 332 may be helpful in diagnosis; however, this may not be readily available through all laboratories 20.

Cicatricial pemphigoid treatment

For the mild disease of the oral mucosa and skin, topical therapies can be effective. Moderate to high potency topical steroids, in gel or ointment form, can be used initially 2 to 3 times per day. The frequency of topical steroid application can be slowly tapered based on patient response. To improve the effectiveness of topical therapies, blotting the area with a disposable tissue to remove moisture before the application of medication may be helpful. Patients may apply the medication with a finger or cotton-swab and rub into the affected areas gently for 30 seconds. Patients should be advised to abstain from eating or drinking for 30 minutes after application to increase absorption 21. Customized prosthetic devices, such as dental trays, can occlude the topical steroid over the affected sites in the mouth 22. Calcineurin inhibitors, such as tacrolimus, have also been reported as a topical therapeutic option 23. Complications of long-term use of topical steroids are uncommon. A cutaneous application may lead to hypopigmentation and atrophy. Although these adverse effects are not commonly seen in the mucous membranes, the risk for oral candidiasis and herpes simplex reactivation is a concern 21. In addition to topical therapies, the importance of oral care has been emphasized as a critical part in the treatment of mucous membrane pemphigoid. This consists of brushing teeth with a soft bristle toothbrush twice daily, flossing daily, and visiting the dentist every 3-6 months 21. If topical therapies are not effective for mild to moderate disease, then dapsone may be effective 24. Typical dose ranges from 50 to 200 mg daily. Systemic corticosteroids can be used in addition to the dapsone.

For mild to moderate ocular involvement, systemic corticosteroids (prednisone 1 to 2 mg/kg/day) alone or in combination with dapsone can be considered. Proper ocular care is important. Since dry eyes are common with ocular pemphigoid, frequent use of lubricants is recommended in the form of artificial tear drops or petrolatum-based ointments. Cleansing away excess exudates from the eyes helps to prevent secondary bacterial infections 21.

For severe or rapidly progressive disease involving the ocular, nasopharyngeal, or anogenital mucosa, a combination of systemic corticosteroids (prednisone 1 to 2 mg/kg/day) plus an additional immunosuppressive agent has been recommended. Immunosuppressive agents that have shown efficacy include azathioprine (1 to 2 mg/kg/day), mycophenolate mofetil (2 to 2.5 g/day) or cyclophosphamide (1 to 2 mg/kg/day) 21. The goal of adjuvant immunosuppressive therapy is to allow taper of prednisone over 6 to 12 months. Intravenous immunoglobulin has been used with success to treat cicatricial pemphigoid 25. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors have been used in the treatment of cicatricial pemphigoid 26. Rituximab has been used alone or as adjuvant therapy for the treatment of mucous membrane pemphigoid 27.

Cicatricial pemphigoid prognosis

Cicatricial pemphigoid is a chronic, progressive disease that results in scarring. Patients require long-term follow-up to monitor for complications as a result of scarring and possible relapse. Due to the potentially serious complications that can arise with cicatricial pemphigoid, it is recommended that therapy is initiated early and aggressively. Patients benefit from a multidisciplinary approach to treatment. Although some patients benefit from immunosuppressive treatment and even have long-term remission, some patients have a refractory disease without a response of disease activity or only temporary control of disease activity with a given treatment 11.

Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid

Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid is considered a subtype of mucous membrane pemphigoid and these terms are sometimes used interchangeably 28. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid is a type of autoimmune conjunctivitis that leads to cicatrization (i.e. scarring) of the conjunctiva 29. If ocular cicatricial pemphigoid is left untreated, it can lead to blindness.

Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid incidence rates are vary between 1 in 12,000 to 60,000 30. A study in the UK found that ocular cicatricial pemphigoid represents 61% of cicatricial conjunctivitis and is estimated to occur with an incidence of 1 in 1 million 31.

Women are affected more than men by a ratio of 2:1 30. Age on onset is usually age 60 to 80 and rarely younger than 30 31. There is no racial predilection 32.

Progression of ocular cicatricial pemphigoid is measured in months and years and, without therapy, results in keratinization of the ocular surface and cicatricial ankyloblepharon (fusion of palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva, not to be confused with congenital palpebral ankyloblepharon, which describes a localized adhesion of the upper and lower eyelids). Though there are reports of spontaneous remission of ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, these cases are the exception.

In terms of medical therapy, chronic steroid-sparing immunomodulators are the mainstay. Dapsone is a common initial agent, but requires initial testing to rule out hemolytic anemia, agranulocytosis, hepatitis, and G6PD deficiency. Agents such as methotrexate, azathioprine and mycophenolate mofetil have also been used. Recent evidence suggests that monotherapy with mycophenolate mofetil controls ocular cicatricial pemphigoid in up to 70% of patients within one year of presentation with fewer side effects than other agents. This evidence was corroborated by the outcome of the present case. Oral corticosteroids are effective at controlling inflammation, but symptoms usually recur once they are tapered. Ahmed and colleagues recommend reserving them only for the most severe inflammation and tapering down within the first 3 months 33. Targeted therapy with monoclonal antibodies (daclizumab and rituximab) has also shown some promise and was recently shown to arrest recalcitrant ocular cicatricial pemphigoid when used in combination with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) 34. When initiating steroid-sparing immunomodulatory therapy, it is reasonable to enlist the help of an internist or rheumatologist to ensure appropriate monitoring. Aggressive lubrication is of utmost importance to optimize the ocular surface—preferably with preservative-free artificial tears and ointment or autologous serum tears if needed. Doxycycline, topical corticosteroids, and cyclosporine can help to reduce inflammation and increase tear production.

Surgical therapy may be indicated when scarring becomes advanced and/or ocular surface decompensation threatens permanent visual decline. Mucous membrane grafting from sites such as the nose and hard palate can slow or relieve cicatrization and treat symblepharon. Medroxyprogesterone can be added to reduce the stimulus for neovascularization.

In stage 4 ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, the type 2 Boston keratoprosthesis may be the only means of preserving or restoring visual function. This device creates a clear aperture through the upper eyelid. The lids are permanently sutured closed resulting in total coverage of the ocular surface.

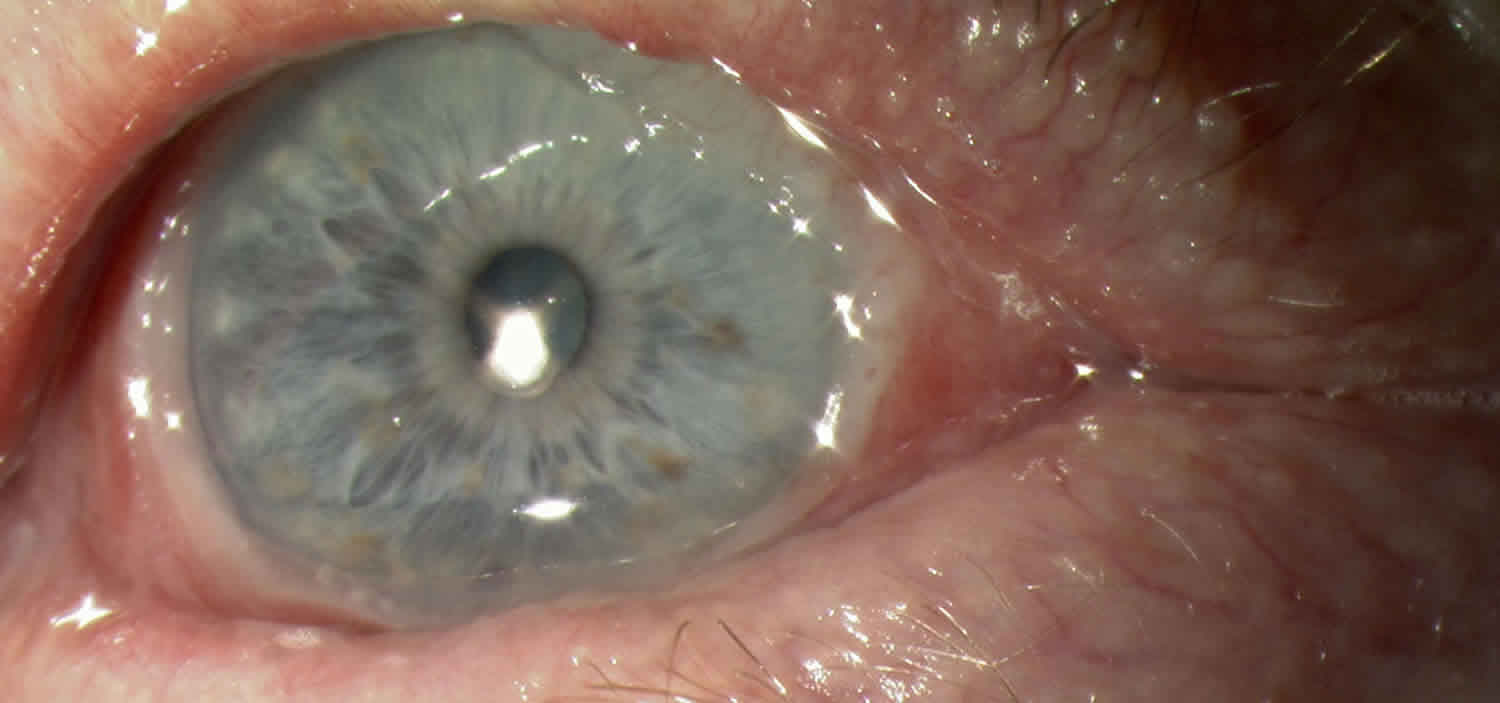

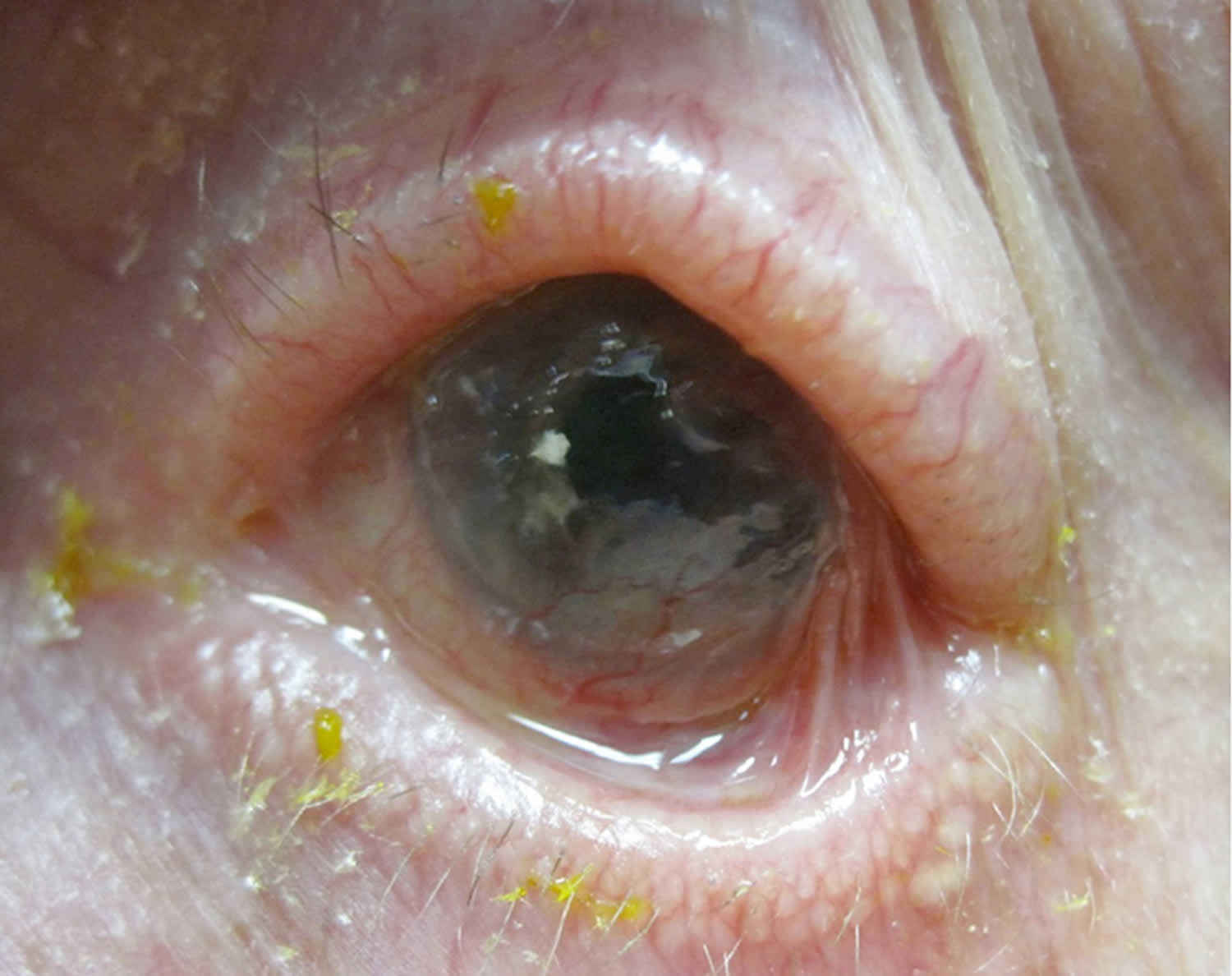

Figure 1. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid

Footnote: This is a patient with typical ocular cicatricial pemphigoid showing symblepharon characteristic of stage 3 disease. Note the rolled edges of the lids with extensive madurosis.

[Source 35 ]Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid causes

The exact cause of ocular cicatricial pemphigoid remains to be elucidated but the existing evidence supports a type 2 hypersensitivity (antibody dependent) response caused by an autoantibody to a cell surface antigen in the basement membrane of the conjunctival epithelium and other similar squamous epithelia 36.

Investigations into the underlying target antigen have led to several possible suspects. The autoantigens responsible for bullous pemphigoid [BP230 (i.e. Bullous pemphigoid antigen 1, a desmoplakin) and BP180 (i.e. Bullous pemphigoid antigen 2, a transmembrane hemidesmosome)] were studied, and the sera of patients with ocular cicatricial pemphigoid was shown to bind these antigens 36. However, further investigation supports that the more likely autoantigen is actually the beta-4 subunit of the alpha-6 beta-4 integrin of hemidesmosomes 37.

Studies of HLA (human leukocyte antigen) typing have found an increased susceptibility to the disease in patients with HLA-DR4 36. The HLA-DQB1*0301 allele in particular shows a strong association with ocular cicatricial pemphigoid and other forms of pemphigoid disease 38. HLA-DQB1*0301 is thought to bind to the beta-4 subunit of the alpha-6 beta-4 integrin (the suspected autoantigen in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid) 39.

Although the exact mechanism remains to be elucidated, the existing evidence supports the production of an autoantibody in susceptible individuals to the beta-4 subunit of the alpha-6 beta-4 integrin of hemidesmosomes in the lamina lucida of the conjunctival basement membrane 37.

Binding of the autoantibody to the autoantigen activates complement, resulting in the cytotoxic destruction of the conjunctival membrane 36. Disruption of the conjunctival basement membrane subsequently leads to bullae formation 40.

The associated cellular inflammatory infiltrate of the epithelium and substantia propria manifests as the chronic conjunctivitis that is the hallmark of this disease 40. Eosinophils and neutrophils mediate inflammation in the early and acute phases of the disease, similar to what is observed in the skin 28. Chronic disease has largely lymphocytic infiltration 28. Fibroblast activation leads to subepithelial fibrosis, which in early disease appears as fine white striae most easily seen in the inferior fornix 41. A scar in the upper palpebral conjunctiva may also be seen. Over time, the fibrotic striae contract, leading to conjunctival shrinkage, symblepharon formation, and forniceal shortening 28. In severe cases of conjunctival fibrosis, entropion, trichiasis and symblepharon may develop, leading to associated keratopathy and corneal vascularization, scarring, ulceration, and epidermalization 41.

The clinical course and severity is variable. Recurrent inflammation causes loss of Goblet cells and obstruction of lacrimal gland ductules, leading to aqueous and mucous tear deficiency 42. The resulting xerosis is severe, and along with progressive subepithelial fibrosis and destruction of limbal stem cells leads to limbal stem cell deficiency and ocular keratinization 37.

Several pro-inflammatory cytokines are found to be elevated in the conjunctival tissues of patients with ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Levels of Interleukin (IL) 1, Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Alpha, migration inhibition factor, and macrophage colony-stimulating factor, and IL-13 have been found to be elevated 40. IL-13 has been found to have a pro-fibrotic and pro-inflammatory effect on conjunctival fibroblasts, and may be implicated in the progressive conjunctival fibrosis that can occur despite clinical quiescence 40.

Additionally, testing of the tears of patients with ocular cicatricial pemphigoid found elevated levels of IL-8, Matrix Metalloproteinase (MMP) 8, MMP-9, and myeloperoxidase (MPO), which are thought to result from neutrophilic infiltrate in patients with ocular cicatricial pemphigoid 43.

Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid symptoms

The commonest symptoms of ocular cicatricial pemphigoid are:

- Inturned eyelashes (trichiasis) rubbing the eye

- Red, gritty sore or dry eyes with sensitivity to light

- Conjunctivitis (red sticky eye) that keeps returning despite courses of antibiotic eyedrops

- Droopiness and closing of the eyelid

If you have inturned eyelashes that often need to be pulled out, it is essential to have a careful assessment by an eye consultant who is expert in diagnosing ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, to evaluate the underlying cause of the inturned eyelashes.

In patients with mucous cicatricial pemphigoid, oral involvement is most common (in 90% of cases), followed by ocular involvement (in 61% of cases) 44. Ocular involvement of mucous cicatricial pemphigoid is considered high risk and carries a poorer prognosis (despite treatment) than when oral mucosa and/or skin alone are affected 31. Up to one third of patients with oral disease progress to ocular involvement 44.

Additional sites of involvement include the oropharynx, nasopharynx, esophagus, larynx, genitalia, and anus 36. The skin is involved in approximately 15% of cases 36. Dysphagia may be a presenting symptom 36.

There are several clinical scoring systems for ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, including schema from Foster, Mondino, and Tauber 31. Clinicians vary in which system they utilize for grading disease clinically and although there are proponents for each system, no consensus exists regarding which system is best to use 45. The existing classification schema are limited by the lack of direct correlation with disease progression and therefore no system can be used to predict need for immunosuppression 45.

Mondino’s Classification System is based on inferior forniceal depth 36. A normal inferior forniceal depth is approximately 11 mm 36.

- Stage 1: up to 25% inferior forniceal depth loss 45

- Stage 2: 25-50% inferior forniceal depth loss 45

- Stage 3: 50-75% inferior forniceal depth loss 45

- Stage 4: greater than 75% inferior forniceal depth loss 45

Foster’s Classification System has four stages as well and is based on specific clinical signs 36:

- Stage 1 Early stage: May include nonspecific symptoms and minimal findings which lead to under-recognition of the disease. Commonly presents as chronic conjunctivitis, tear dysfunction, and subepithelial fibrosis 36 Subepithelial fibrosis manifests as fine gray-white striae in the inferior fornix. Signs and symptoms are usually bilateral, and may be asymmetric.

- Stage 2 Shortening of the fornices. A normal inferior forniceal depth is approximately 11 mm. A reduced inferior forniceal depth is abnormal and should prompt further investigation 36

- Stage 3 Symblepharon formation. Can be detected by pulling the lower eyelid down while the patient looks up and vice versa 36

- Stage 4 Ankyloblepharon. Represents end-stage disease, with surface keratinization, and extensive adhesions between the eyelid and the globe, resulting in restricted motility 36

Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid diagnosis

Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid diagnosis is based on clinical signs and positive direct immunofluorescence testing of the conjunctiva 29. The gold standard for diagnosis is conjunctival biopsy with direct immunofluorescence testing for IgG, IgA, IgM, and C3. Positive staining reveals a linear pattern in the basement membrane zone of the conjunctival epithelium similar to that seen in other anti-basement-membrane-antibody conditions such as Goodpasture disease of the kidney. Conjunctival biopsy of an actively involved area is needed and the conjunctival tissue must be submitted unfixed for analysis 29. If involvement is diffuse, biopsy of the inferior conjunctival fornix is recommended 36. Judicious biopsy is advisable as ocular cicatricial pemphigoid is an obliterating disease of the conjunctiva and only the minimal amount of tissue necessary should be removed. Alternatively, biopsy of an active oral mucosa lesion can be diagnostic as well 36.

Immunofluorescence reveals linear staining of the epithelial basement membrane zone 31. The sensitivity of immunofluorescence may be as low as 50%, especially for longstanding/severe cicatrization because of the loss of immunoreactants and the destruction of basement membrane in longstanding disease 29.

Serological testing is not routinely used in diagnosis. Sequential photographs are useful to monitor clinical progression 30.

Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid treatment

Without treatment, ocular cicatricial pemphigoid progresses in up to 75% of patients 46. While systemic treatment stops progression of cicatrization in most patients, it fails in approximately 10% of them 46. Systemic therapy is necessary in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid as ocular involvement comprises a high risk subset of mucous membrane pemphigoid and is insufficiently treated with topical therapy alone. Systemic treatment is best managed by a physician trained in the management of anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory treatment given the significant risk of systemic complications necessitating frequent blood test monitoring 31. Several drugs are effective in treating ocular cicatricial pemphigoid and a step-wise approach of escalation of therapy when there is insufficient response is recommended 47.

Topical therapy can be used as an adjunct for surface disease but should not be used in place of systemic therapy. Topical therapy includes optimizing lubrication of the ocular surface with artificial tears and punctual plugging 47. Topical and subconjunctival steroids can relieve symptoms but are ineffective for treatment of the underlying disease 47. Topical cyclosporine has been found to be ineffective while topical tacrolimus has been shown to be successful in small case series 30. Subconjunctival mitomycin-c has also been investigated in small case series with variable effect 47.

If the disease remains quiescent following a few years of systemic therapy, many practitioners are often able to discontinue systemic therapy successfully 47. However, it is important to continue to monitor the patient for recurrence of disease as up to 22% of patients relapse 47.

Complications

Seemingly trivial surgical intervention and conjunctival trauma can lead to serious exacerbation of disease 36. Surgical intervention, such treatment of trichiasis, entropion and cataract should be deferred if possible until control of active disease is achieved 30. In some situations this may not be possible and a multi-disciplinary approach is best 30.

Inferior eyelid retractor plication for trichiasis avoids surgery on the conjunctiva and has been shown to be safe and effective when undertaken in the setting clinically quiescent ocular cicatricial pemphigoid 48. Cryotherapy for the treatment of trichiasis has also been shown to be safe and moderately effective when undertaken in the setting clinically quiescent ocular cicatricial pemphigoid 49. In a case series of patients with well controlled ocular cicatricial pemphigoid undergoing entropion repair, successful repair was performed in all patients regardless of type of surgery 50.

Safe and successful performance of cataract surgery has been shown in several case series of patients with well-controlled ocular cicatricial pemphigoid.[32] [33] A clear corneal incision is recommended to reduce the risk of exacerbation 51.

Glaucoma is also a possible complication of ocular cicatricial pemphigoid and is particularly difficult to diagnose and treat. IOP measurements are unreliable, and examination and ancillary testing are limited by ocular surface disease. A case series of 61 patients with severe ocular cicatricial pemphigoid found that 21% of patients also had glaucoma and an additional 9% developed glaucoma over the course of the follow-up 52.

Persistent epithelial defect may need amniotic membrane graft or ProkeraⓇ.

ocular cicatricial pemphigoid has been described in patients with other concurrent rheumatologic illnesses including rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and HLA-B27 spondyloarthropathies 53.

Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid treatment options

Mild Disease

Dapsone is an effective and commonly used anti-inflammatory treatment in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid for mild disease and in the absence of rapid progression 31. Dapsone is started at a dose of 50 mg/day and slowly increased as tolerated by up to 25mg every 7 days to an effective dose, which is usually between 100-200mg/day 31. If significant improvement is not achieved within 3 months, escalation of therapy is recommended such as to azathioprine or methotrexate 47.

Systemic complications of dapsone include hemolysis and methemoglobinemia 31. G6PD (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) deficiency is a contraindication to dapsone therapy as dapsone can precipitate a hemolytic crisis 31. All patients should be screened for G6PD deficiency before initiation of therapy with dapsone 31.

Sulphapyridine is also an oral antibiotic and is a well-tolerated alternative in patients with mild disease who are unable to take dapsone 54. Sulphapyridine’s efficacy (effective in approximately 50% of patients) is lower than dapsone however 54.

Moderate to Severe Disease

Corticosteroids have a rapid effect and are useful during the acute phase of severe or rapidly progressive disease 31. Adjuvant corticosteroid-sparing immunomodulatory/immunosuppressive therapy should be initiated simultaneously as it may take weeks to become therapeutic 31. This will allow a quicker taper from steroids and the shortest course of steroid therapy necessary given the significant systemic side effects of long-term steroid therapy 31. Generally, one quiescence is achieved, steroids are tapered slowly.[22] Screening for tuberculosis (TB) is recommended prior to the initiation of steroid therapy 31.

Azathioprine has been shown to be an effective steroid sparing therapy 47. It takes 8-12 weeks of treatment to achieve maximal effect and thus should be used initially concurrently with steroids 31. Screening for thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) deficiency is recommended prior to initiation of azathioprine as TPMT-deficient patients are at higher risk of developing mvelosuppression 31. Systemic complications include leukopenia, pancytopenia, infection, malignancy, and drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome 47.

Methotrexate has been shown to be an effective monotherapy for ocular cicatricial pemphigoid with fewer adverse effects when compared to azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, and dapsone 31. The Systemic Immunosuppressive Therapy for Eye Diseases (SITE) trial found that cyclophosphamide was effective in controlling inflammation in 70.7% of patients with ocular cicatricial pemphigoid at 1 year, with 66.9% patients on less than or equal to 10mg of prednisone 55. Low dose methotrexate is particularly effective in mild to moderate ocular cicatricial pemphigoid 31. Systemic complications include hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, pneumonitis, pulmonary fibrosis, pancytopenia, and malignancy 47.

Tetracyclines are a well-tolerated anti-inflammatory agent and have been found to be effective for mild to moderate ocular cicatricial pemphigoid, particularly when combined with nicotinamide 31.

Mycophenolate mofetil has been shown to be a well tolerated and effective therapy for ocular cicatricial pemphigoid 47. Therapeutic dosage is usually 1000-2000mg/day 47. Systemic complications include leukopenia 47.

Cyclosporine has only been used in small series of patients and has been reported to have variable levels of effectiveness 31.

Severe Disease

Cyclophosphamide is first line in patients with severe disease or rapid progression 31. It should be started in conjunction with steroids and can be dosed orally or IV 31. A short course of pulsed IV therapy (ex. 3 days) can be particularly effective in achieving rapid control if needed, such as prior to surgery 47. The SITE trial found that cyclophosphamide was effective in controlling inflammation in 80.8% of patients with ocular cicatricial pemphigoid at 1 year, with 58.5% of patients on less than or equal to 10mg of prednisone 56. Systemic complications include myelosuppression, carcinogenesis, and teratogenicity 47.

Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG) is reserved for patients with progressive disease that is unresponsive to systemic steroids and cyclophosphamide and has been found to be an effective therapy 47. Dosing is every 3-4 weeks until quiescence is achieved, usually requiring 4-12 cycles 47. Systemic complications are severe, and include anaphylaxis, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), aseptic meningitis, and acute renal failure 47. Therefore, IVIG is which is reserved for refractory disease.

Biologics, including the anti-TNF agents Etanercept and infliximab, the IL-2 antagonist daclizumab, and the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab have been shown to be efficacious in small studies of patients with refractory ocular cicatricial pemphigoid 31. The combination of IVIG and rituximab has been shown to be effective as well in refractory ocular cicatricial pemphigoid 31.

Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid prognosis

The course of ocular cicatricial pemphigoid is characterized by chronic relapsing and remitting cicatrizing conjunctivitis and progressive conjunctival subepithelial fibrosis causing distorted anatomy, such as trichiasis and entropion, tear film abnormalities (exposure and meibomian gland dysfunction), and limbal stem cell deficiency, results in severe corneal epitheliopathy, persistent epithelial defect, corneal stromal ulceration, secondary infection, corneal neovascularization, and blindness. In the end, the cornea is fully scarred, vascularized, and keratinized. Unfortunately some patients can permanently lose their eyesight due to ocular cicatricial pemphigoid causing permanent scarring of the cornea, the clear front window of the eye, as a consequence of severe dryness, corneal infection or damage to limbal stem cells. It may take 10 to 30 years to reach this endstage. Of 111 patients, 26% had glaucoma, most with advanced, with a long history of medication use, optic nerve damage, and visual field loss 57.

In a few patients, the condition can go into remission for 1 year or more and the immunosuppressive medication can be stopped. However the majority of mucous membrane pemphigoid patients continue on oral immunosuppressive medication for life.

The only medication which has been reported to put ocular cicatricial pemphigoid into remission for more than 1 year is cyclophosphamide, which is effective but can cause side effects.

References- Tolaymat L, Hall MR. Cicatricial Pemphigoid. [Updated 2019 Jun 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK526120

- Bernard P, Vaillant L, Labeille B, Bedane C, Arbeille B, Denoeux JP, Lorette G, Bonnetblanc JM, Prost C. Incidence and distribution of subepidermal autoimmune bullous skin diseases in three French regions. Bullous Diseases French Study Group. Arch Dermatol. 1995 Jan;131(1):48-52

- Zillikens D, Wever S, Roth A, Weidenthaler-Barth B, Hashimoto T, Bröcker EB. Incidence of autoimmune subepidermal blistering dermatoses in a region of central Germany. Arch Dermatol. 1995 Aug;131(8):957-8.

- Laskaris G, Sklavounou A, Stratigos J. Bullous pemphigoid, cicatricial pemphigoid, and pemphigus vulgaris. A comparative clinical survey of 278 cases. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1982 Dec;54(6):656-62

- Hong GH, Khan IR, Shifera AS, Okeagu C, Thorne JE. Incidence and Clinical Characteristics of Ocular Involvement in Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2018 Apr 19;:1-5

- Chan LS, Wang T, Wang XS, Hammerberg C, Cooper KD. High frequency of HLA-DQB1*0301 allele in patients with pure ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Dermatology (Basel). 1994;189 Suppl 1:99-101.

- Balding SD, Prost C, Diaz LA, Bernard P, Bedane C, Aberdam D, Giudice GJ. Cicatricial pemphigoid autoantibodies react with multiple sites on the BP180 extracellular domain. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1996 Jan;106(1):141-6

- Domloge-Hultsch N, Gammon WR, Briggaman RA, Gil SG, Carter WG, Yancey KB. Epiligrin, the major human keratinocyte integrin ligand, is a target in both an acquired autoimmune and an inherited subepidermal blistering skin disease. J. Clin. Invest. 1992 Oct;90(4):1628-33.

- Tyagi S, Bhol K, Natarajan K, Livir-Rallatos C, Foster CS, Ahmed AR. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid antigen: partial sequence and biochemical characterization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996 Dec 10;93(25):14714-9

- Lee JB, Liu Y, Hashimoto T. Cicatricial pemphigoid sera specifically react with the most C-terminal portion of BP180. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2003 Jun;32(1):59-64.

- Fleming TE, Korman NJ. Cicatricial pemphigoid. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2000 Oct;43(4):571-91; quiz 591-4.

- Bhol KC, Dans MJ, Simmons RK, Foster CS, Giancotti FG, Ahmed AR. The autoantibodies to alpha 6 beta 4 integrin of patients affected by ocular cicatricial pemphigoid recognize predominantly epitopes within the large cytoplasmic domain of human beta 4. J. Immunol. 2000 Sep 01;165(5):2824-9.

- Li X, Qian H, Sogame R, Hirako Y, Tsuruta D, Ishii N, Koga H, Tsuchisaka A, Jin Z, Tsubota K, Fukumoto A, Sotozono C, Kinoshita S, Hashimoto T. Integrin β4 is a major target antigen in pure ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid. Eur J Dermatol. 2016 Jun 01;26(3):247-53.

- Lazor JB, Varvares MA, Montgomery WW, Goodman ML, Mackool BT. Management of airway obstruction in cicatricial pemphigoid. Laryngoscope. 1996 Aug;106(8):1014-7

- Tyagi S, Bhol K, Natarajan K, Livir-Rallatos C, Foster CS, Ahmed AR. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid antigen: partial sequence and biochemical characterization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996 Dec 10;93(25):14714-9.

- Bédane C, McMillan JR, Balding SD, Bernard P, Prost C, Bonnetblanc JM, Diaz LA, Eady RA, Giudice GJ. Bullous pemphigoid and cicatricial pemphigoid autoantibodies react with ultrastructurally separable epitopes on the BP180 ectodomain: evidence that BP180 spans the lamina lucida. J. Invest. Dermatol. 1997 Jun;108(6):901-7.

- Bean SF, Waisman M, Michel B, Thomas CI, Knox JM, Levine M. Cicatricial pemphigoid. Immunofluorescent studies. Arch Dermatol. 1972 Aug;106(2):195-9.

- Leonard JN, Wright P, Williams DM, Gilkes JJ, Haffenden GP, McMinn RM, Fry L. The relationship between linear IgA disease and benign mucous membrane pemphigoid. Br. J. Dermatol. 1984 Mar;110(3):307-14.

- Shimanovich I, Nitz JM, Zillikens D. Multiple and repeated sampling increases the sensitivity of direct immunofluorescence testing for the diagnosis of mucous membrane pemphigoid. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2017 Oct;77(4):700-705.e3

- Yasukochi A, Teye K, Ishii N, Hashimoto T. Clinical and Immunological Studies of 332 Japanese Patients Tentatively Diagnosed as Anti-BP180-type Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid: A Novel BP180 C-terminal Domain Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2016 Aug 23;96(6):762-7

- Knudson RM, Kalaaji AN, Bruce AJ. The management of mucous membrane pemphigoid and pemphigus. Dermatol Ther. 2010 May-Jun;23(3):268-80.

- Aufdemorte TB, De Villez RL, Parel SM. Modified topical steroid therapy for the treatment of oral mucous membrane pemphigoid. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1985 Mar;59(3):256-60.

- Assmann T, Becker J, Ruzicka T, Megahed M. Topical tacrolimus for oral cicatricial pemphigoid. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2004 Nov;29(6):674-6.

- Rogers RS, Seehafer JR, Perry HO. Treatment of cicatricial (benign mucous membrane) pemphigoid with dapsone. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1982 Feb;6(2):215-23.

- Ma L, You C, Hernandez M, Maleki A, Lasave A, Schmidt A, Stephenson A, Zhao T, Anesi S, Foster CS. Management of Ocular Cicatricial Pemphigoid with Intravenous Immunoglobulin Monotherapy. Ocul. Immunol. Inflamm. 2018 Mar 08;:1-7

- Prey S, Robert PY, Drouet M, Sparsa A, Roux C, Bonnetblanc JM, Bédane C. Treatment of ocular cicatricial pemphigoid with the tumour necrosis factor alpha antagonist etanercept. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2007;87(1):74-5.

- Maley A, Warren M, Haberman I, Swerlick R, Kharod-Dholakia B, Feldman R. Rituximab combined with conventional therapy versus conventional therapy alone for the treatment of mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP). J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2016 May;74(5):835-40.

- Arafat SN, Suelves AM, Spurr-Michaud S, et al. Neutrophil Collagenase, Gelatinase and Myeloperoxidase in Tears of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Ocular Cicatricial Pemphigoid Patients. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(1):79-87

- Ophthalmic Pathology and Intraocular Tumors. Basic and Clinical Science Course (BCSC). American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2014; pp54-56.

- DaCosta J. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid masquerading as chronic conjunctivitis: a case report. Clinical Ophthalmology. 2012;6:2093-2095.

- Xu H-H, Werth VP, Parisi E, Sollecito TP. Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid. Dental clinics of North America. 2013;57(4):611-630.

- Ocular Cicatricial Pemphigoid. https://uveitis.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/ocular_cicatricial_pemphigoid.pdf

- Ahmed M, Zein G, Khawaja F, Foster CS. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid: pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Prog Retin Eye Res 2004 Nov;23(6):579-592.

- Foster CS, Chang PY, Ahmed AR. Combination of rituximab and intravenous immunoglobulin for recalcitrant ocular cicatricial pemphigoid: a preliminary report. Ophthalmology 2010 May;117(5):861-869.

- Ocular Cicatricial Pemphigoid: Atypical presentation as pseudopterygium and limbal stem cell deficiency. https://webeye.ophth.uiowa.edu/eyeforum/cases/122-limbal-OCP.htm

- External Disease and Cornea. Basic and Clinical Science Course (BCSC). American Academy of Ophthalmology, 2014; pp344-345.

- Zakka LR, Reche P, Ahmed AR. Role of MHC Class II Genes in the pathogenesis of pemphigoid. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2011;(11):40–47.

- Ahmed AR, Foster S, Zaltas M, et al. Association of DQw7 (DQB1*0301) with ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1991;88(24):11579-11582

- Yunis JJ, Mobini N, Yunis EJ, et al. Common major histocompatibility complex class II markers in clinical variants of cicatricial pemphigoid. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1994;91:7747-7751.

- Saw VPJ, Offiah I, Dart RJ, et al. Conjunctival Interleukin-13 Expression in Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid and Functional Effects of Interleukin-13 on Conjunctival Fibroblasts in Vitro. Am J Pathol. 2009;175 (6):2406-2415.

- Saw VPJ, Schmidt E, Offiah I, et al. Profibrotic Phenotype of Conjunctival Fibroblasts from Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid. Am J Pathol. 2011;178(1):187-197.

- Creuzot-Garcher C, H-Xuan T, Bron AM, et al. Blood group related antigens in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Br J Ophthalmol. 2004;88:1247–1251.

- Chan MF, Sack R, Quigley DA, et al. Membrane Array Analysis of Tear Proteins in Ocular Cicatricial Pemphigoid. Optometry and vision science : official publication of the American Academy of Optometry. 2011;88(8):1005-1009.

- Higgins GT, Allan RB, Hall R, Field EA, Kaye SB. Development of ocular disease in patients with mucous membrane pemphigoid involving the oral mucosa. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90(8):964-967.

- Elder MJ, Bernauer W, Leonard J, Dart JK. Progression of disease in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80(4):292-296.

- Heiligenhaus A, Schaller J, Mauss S, et al. Eosinophil granule proteins expressed in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82(3):312-317.

- Neff AG, Turner M, Mutasim DF. Treatment strategies in mucous membrane pemphigoid. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4(3):617-626.

- Elder MJ, Dart JK, Collin R. Inferior retractor plication surgery for lower lid entropion with trichiasis in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79(11):1003-1006.

- Elder MJ, Bernauer W. Cryotherapy for trichiasis in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78(10):769-771.

- Gibbons A, Johnson TE, Wester ST, et al. Management of Patients with Confirmed and Presumed Mucous Membrane Pemphigoid Undergoing Entropion Repair. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159(5):846–852.

- Puranik CJ, Murthy SI, Taneja M, Sangwan VS. Outcomes of cataract surgery in ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2013;21(6):449-54.

- Miserocchi E1, Baltatzis S, Roque MR, et al. The effect of treatment and its related side effects in patients with severe ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(1):111-8.

- Kaushik P, Ghate K, Nourkeyhani H, et al. Pure ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid in a patient with axial spondyloarthritis (HLA-B27 positive). Rheumatology. 2013;52:2097-2099.

- Elder MJ, Leonard J, Dart JK. Sulphapyridine–a new agent for the treatment of ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Br J Ophthalmol. 1996;80(6):549-552.

- Gangaputra S, Newcomb CW, Liesegang TL, et al. Methotrexate for Ocular Inflammatory Diseases. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(11):2188-98.e1

- Pujari SS, Kempen JH, Newcomb CW, et al. Cyclophosphamide for ocular inflammatory diseases. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(2):356.

- Glaucoma in patients with ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Ophthalmology. 1989 Jan;96(1):33-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2645551