Constitutional growth delay

Constitutional growth delay also called constitutional delay of growth and puberty, is a variant of normal growth rather than a disorder. Children with constitutional delay of growth and puberty, the most common cause of short stature and delayed puberty, typically have retarded linear growth within the first 3 years of life 1. In constitutional delay of growth and puberty (in which statural growth falls below 5% of the growth curve after 1–2 years of age and is further delayed due to late start to puberty), linear growth velocity and weight gain slows beginning as young as age 3-6 months, resulting in downward crossing of growth percentiles, which often continues until age 2-3 years. At that time, growth resumes at a normal rate, and these children grow either along the lower growth percentiles or beneath the curve but parallel to it for the remainder of the prepubertal years 2.

Estimates are that about 15% of patients referred to a specialist due to short stature have constitutional growth delay. Constitutional growth delay is twice as common in boys compared to girls; although some of the male referrals may be just concerns regarding their height compared to their peers rather than an actual delay 2.

At the expected time of puberty, the height of children with constitutional growth delay begins to drift further from the growth curve because of delay in the onset of the pubertal growth spurt. Catch-up growth, onset of puberty and pubertal growth spurt occur later than average, resulting in normal adult stature and sexual development. However, a report by Rohani et al 3 on males with constitutional growth delay—mean age 15.2 years at presentation and 20 years at study’s end—found that the majority of patients attained neither their target height nor their predicted adult height. The mean final or near-final height reached by the subjects was 165.7 cm, compared with a predicted adult height of 170.7 cm and a target height of 171.8 cm.

Although constitutional growth delay is a variant of normal growth rather than a disorder, delays in growth and sexual development may contribute to psychological difficulties, warranting treatment for some individuals. Studies have suggested that referral bias is largely responsible for the impression that normal short stature per se is a cause of psychosocial problems; nonreferred children with short stature do not differ from those with more normal stature in school performance or socialization 4.

Constitutional growth delay is seen in approximately 15% of children and can appear at different stages of their development. It’s important to remember that growth velocity varies accordingly. Between 3 to 6 months to 2 to 3 years of age, the expectation is that some children will cross percentiles in their growth and weight charts without actual concerns for a delay in growth. This tendency will typically resume to a standard rate after this period. After four years of age, there is constant steady growth. It is not until puberty when one will notice that the child starts to divert from the curve, usually because they have late onset of puberty that corresponds to a delay bone age 5.

Physical examination findings in patients with constitutional growth delay are essentially normal, with the exception of immature appearance for age. Body proportions may reflect the delay in growth. During childhood, the upper-to-lower body ratio may be greater than normal, reflecting more infantile proportions. In adults, the ratio is often reduced (ie, < 1 in whites, < 0.9 in blacks) as a result of the longer period of leg (long bone) growth 6.

Medical care in constitutional growth delay is aimed at obtaining several careful growth measurements at frequent intervals, often every 6 months. These measurements are used to calculate linear height velocities and establish a trajectory on the growth curve. Medical treatment of this variation of normal growth is not necessary but may be initiated in adolescents experiencing psychosocial distress 4.

Short stature key points

By definition, normal growth encompasses the 95% confidence interval (CI) for a specific population 1. Most children who have a normal growth pattern but remain below the lower 2.5 percentile (approximately −2.0 standard deviations [SD]) are otherwise normal. The further below −2.0 SD (2.5 percentile) an individual’s growth falls, the more likely it is that there is a pathological condition keeping him or her from achieving their genetically determined height potential. Growth retardation refers to a downward deflection of the growth velocity with the resultant growth curve crossing the SD lines or percentiles.

It is important to remember that only about 3% of short stature patients have an actual endocrinologic problem that will need further treatment, which is why it is important to take a good history. If there is a concern in growth delay after proper height documentation, the patient needs to be sent for growth hormone (GH) levels, IGF-1 and bone age. If this results within normal limits including a delay in bone age that correlates with the height of the patient, most likely it is safe to continue to monitor the patient. If taking this approach, and any of the laboratory workup or bone age are uncertain, or this type of lab workup cannot be done or properly interpreted, a specialist referral is in order.

These are other recommendations on when to refer a patient 7:

- Any patient who is below two standard deviations on their height

- Any patient whos growth velocity is below the expected one in a 6 to 12 months period follow up. (please see up for normal growth velocities by age)

- Any patient that crosses two percentile lines for their height (even if still within “normal” standard deviations)

- Patient with known or suspected comorbidities (thyroid disorder, turner, septo-optic dysplasia, etc.) – this type of population will need a full workup

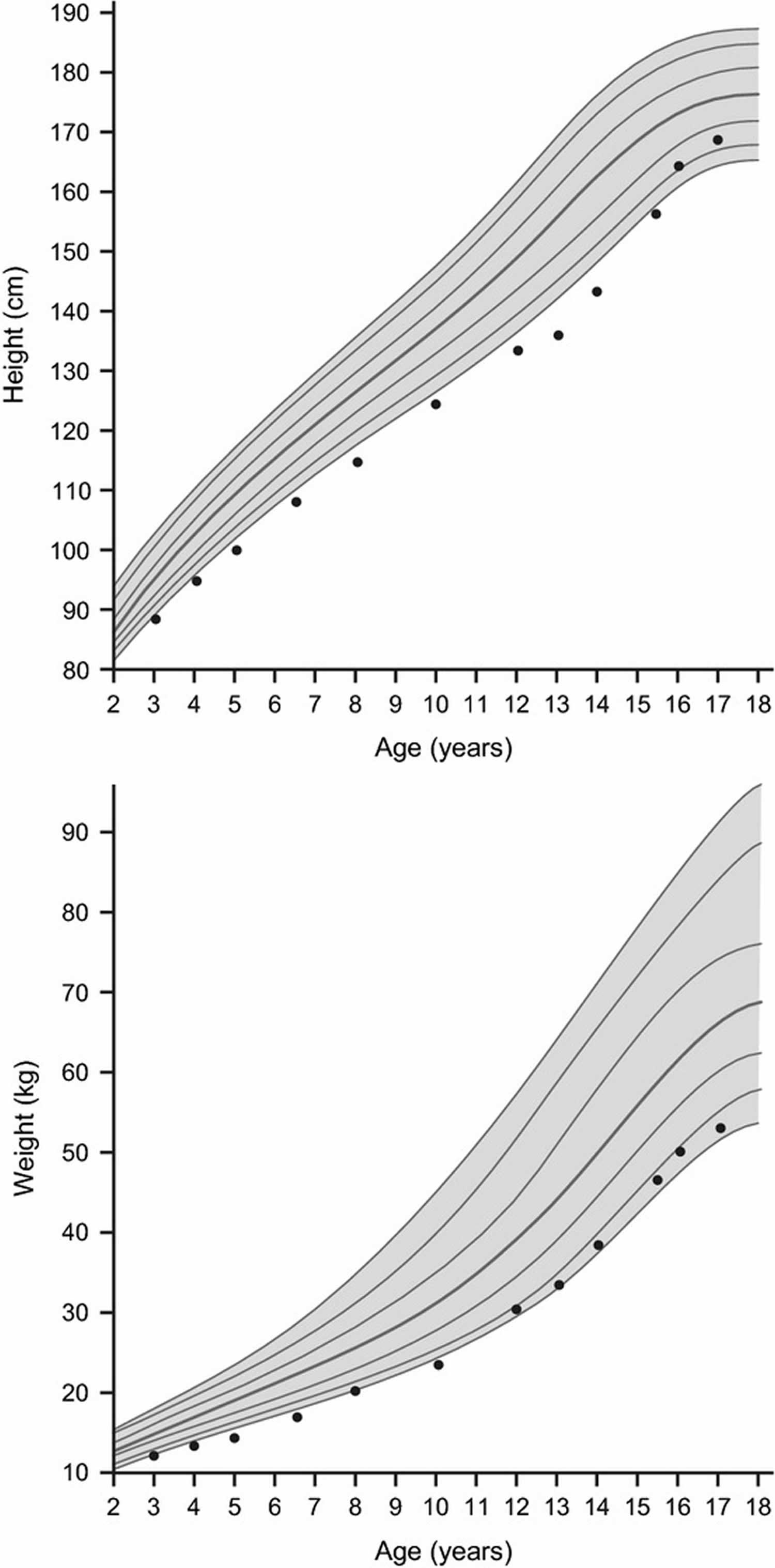

Figure 1. Constitutional growth delay

Footnote: Data are for a representative growth curve showing the 3rd, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, 97th percentiles. Dots show a typical growth curve for a child with constitutional growth delay.

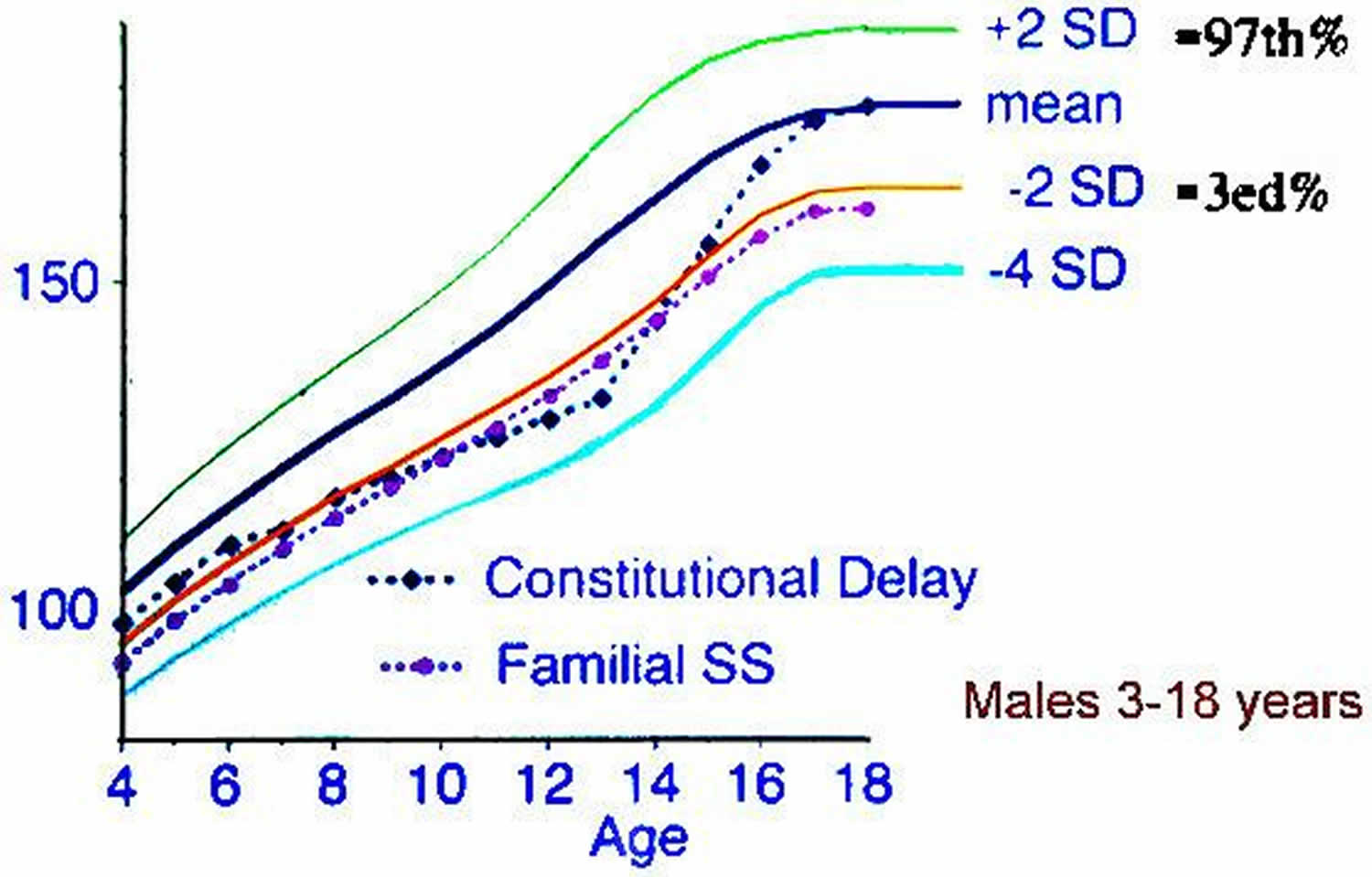

[Source 1 ]Figure 2. Comparison of the growth patterns between idiopathic short stature and constitutional growth delay

Footnote: Constitutional growth delay and familial short stature (Familial SS) are the most common cause of short stature. A child with constitutional delay of growth is growing at his/her normal rate and will eventually catch up to the curve. In familial short stature, the infant has a constant growth rate, but one or both parents are short. This situation typically occurs in parents whom mothers are below 152 cm and fathers 160 cm respectively.

Constitutional growth delay causes

Constitutional growth delay is thought to be inherited from multiple genes from both parents. The strong role of heredity is reflected in the 60-90% likelihood of this growth pattern in a family member of the same or opposite sex. A delay in the reactivation of the hypothalamic-pituitary pulse generator results in a later onset of puberty 8.

A study by Barroso et al 9 suggested that familial and sporadic constitutional delay of growth and puberty are marked by genetic heterogeneity, with the investigators finding that in 15 out of 59 patients with these forms of the condition, 15 rare heterozygous missense variants existed in seven different genes (IGSF10, GHSR, CHD7, SPRY4, WDR11, SEMA3A, IL17RD).

Hussein et al. 10 conducted a prospective study in which they classify the short stature etiology, and found within their population that 26% were the result of endocrine disorders; 11.8% ad GH deficiency, of which 63.6% had normal GH variants, 15.8% had constitutional growth delay, while a combination of both was present in about 5%.

Constitutional growth delay inheritance pattern

Constitutional growth delay may be inherited as an autosomal dominant, recessive, or X-linked trait 11.

Constitutional growth delay differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis will vary depending on the clinical presentation as well as age; the most common differential diagnosis in infancy is the failure to thrive followed by cardiac abnormalities. As children grow the diagnosis becomes broader.

- Delayed puberty: Patient will have short stature, but will also have other features that point towards a delay in puberty.

- Hypothyroidism: Most often this condition is diagnosed in the first week of life, for some cases that are either mild at birth or go unrecognized, growth is very slow compared to growth hormone deficiency, having a very low percentile in their growth height.

- Growth hormone (GH) insensitivity: there are reports of rare cases of patients who have malfunctioned GH receptors.

- Turner syndrome: growth failure is universal in individuals with Turner syndrome, which results from haploinsufficiency of SHOX. Some times this disease has no evidence of skeletal dysplasia or other clinical anomalies but just the short stature 12.

There is also a mass effect that results in comorbidities such as diabetes insipidus, hypopituitarism, growth hormone deficiency 13.

Causes of short stature 1:

- Primary growth failure

- Clinically defined syndromes including Down syndrome, Turner syndrome, Noonan syndrome, Prader–Willi syndrome and Silver–Russell syndrome

- Small for gestational age (SGA) with failure of catch-up growth

- Congenital bone dysplasia, for example, achondroplasia, hypochondroplasia

- Secondary growth disorders

- Endocrine causes

- Growth hormone deficiency (GHD) either congenital or acquired (hypothalamic-pituitary region lesions such as craniopharyngioma or head trauma)

- Multiple pituitary deficiencies

- Cushing syndrome

- Hypothyroidism

- Consequences of precocious puberty

- Other disorders of the GH–IGF-I axis

- IGF-I deficiency

- ALS-deficiency

- IGF-I resistance

- Metabolic disorders

- Poorly controlled diabetes mellitus

- Disorders of lipid, carbohydrate, protein metabolism, for example, chronic renal insufficiency

- Disorders in organ systems and systemic disorders, for example, cardiac, pulmonary (cystic fibrosis), liver, intestinal (short bowel syndrome and coeliac disease), renal, chronic anemia, juvenile arthritis

- Psychosocial conditions such as emotional deprivation, anorexia nervosa

- Systemic or local glucocorticoid therapy

- Treatment of childhood malignancy, for example, chemotherapy, total body irradiation

- Endocrine causes

Constitutional growth delay symptoms

Constitutional growth delay is a global delay in development that affects every organ system. Delays in growth and sexual development are quantified by skeletal age, which is determined from bone age radiographic studies of the left hand and wrist. Growth and development are appropriate for an individual’s biologic age (skeletal age) rather than for their chronologic age. Timing and tempo of growth and development are delayed in accordance with the biologic state of maturity.

Individuals with constitutional growth delay are usually of normal size at birth. Deceleration in both height and weight velocity typically occurs within the first 3-6 months of life. This shift downward is similar to that observed in infants experiencing normal lag-down growth but tends to be more severe and prolonged. Individual variation is substantial; however, most children resume a normal growth velocity by age 2-3 years. During childhood, these individuals grow along or parallel to the lower percentiles of the growth curve.

Indeed, looking at height changes from birth to age 5 years, a study by Rothermel et al 14 found that in children with either constitutional growth delay or familial short stature, there was a greater decrease in the height standard deviation score (SDS) in the first 2 years of life than between ages 2 and 5 years, while in children with idiopathic growth hormone deficiency, there was a steady decrease in height standard deviation score during the first 5 years of life.

Similarly, a retrospective study by Reinehr et al 15 indicated that various differences in height standard deviation score and body mass index (BMI) standard deviation score can help to distinguish constitutional delay of growth and puberty from hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. For example, unlike boys with constitutional delay of growth and puberty, those with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism did not experience significantly decreased height standard deviation score and BMI standard deviation score in the first 2 years of life. Moreover, at pubertal age, boys with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism had a significantly higher BMI standard deviation score than did those with constitutional delay of growth and puberty.

Skeletal age, which is estimated from radiographic studies of the left hand and wrist, is usually delayed in constitutional growth delay (typically 2-4 years by late childhood) and is most consistent with the child’s height age (age for which a child’s height is at the 50th percentile) rather than the child’s chronologic age.

Because the timing of the onset of puberty, pubertal growth spurt, and epiphyseal fusion are determined by a child’s skeletal age (biologic age), children with constitutional growth delay are often referred to as “late bloomers.”

At the usual age for puberty, these children continue to grow at a prepubertal rate appropriate for their biologic stage of development. Natural slowing of linear growth just before onset of puberty may be exaggerated, emphasizing the difference in size from peers who are accelerating in growth. The timing of the pubertal growth spurt is delayed, and the spurt may be prolonged with a lower peak height velocity. In patients with both constitutional growth delay and familial short stature, the degree of growth retardation may appear more severe, but the adult height is appropriate for the genetic background.

Constitutional growth delay complications

Other than psychosocial issues resulting from differences in stature and sexual development from peer groups, constitutional growth delay is a benign condition 16.

As infants, delay in bone age may also manifest as delays in motor skills and control of bowel or bladder function as a result of immature muscular development.

Long-term consequences of constitutional growth delay are now recognized and may include height at the lower end of the reference range for an individual’s family and osteopenia. The height deficit at the onset of puberty, shorter period between the onset of puberty and the adolescent growth spurt, and lower peak height velocity can contribute to a slightly lower adult height. Data on bone density are more conflicting. Osteopenia during adulthood is a concern because of the potential for reduced bone accrual during adolescence. Bone mineralization increases most in girls aged 11-14 years and in boys aged 14-17 years. More than half of adult bone calcium accumulates during this pubertal period. Delays in circulating sex steroids and resultant increases in growth hormone concentrations may lead to permanent deficiencies in bone mass. Some studies show that, although decreases in total bone that may be related to reduced limb bone mass and size may be present, volumetric density is normal.

Constitutional growth delay diagnosis

Constitutional growth delay in children with slow growth or delayed puberty is a diagnosis of exclusion. Evaluation excludes hormonal deficiencies, occult systemic illness, or syndromes associated with growth impairment as potential underlying causes.

A radiographic study of the left hand and wrist to assess skeletal maturation is critical in diagnosing constitutional growth delay. Typically, the bone age begins to lag behind chronologic age during early childhood and is delayed in adolescence by an average of 2-4 years.

Physical examination

Physical examination findings in patients with constitutional growth delay are essentially normal, with the exception of immature appearance for age. Body proportions may reflect the delay in growth. During childhood, the upper-to-lower body ratio may be greater than normal, reflecting more infantile proportions. In adults, the ratio is often reduced (ie, < 1 in whites, < 0.9 in blacks) as a result of the longer period of leg (long bone) growth 6.

Laboratory studies

Constitutional growth delay in children with slow growth or delayed puberty is a diagnosis of exclusion. Evaluation excludes hormonal deficiencies, occult systemic illness, or syndromes associated with growth impairment as potential underlying causes.

Hormonal evaluation

Thyroid function

Thyroxine (T4) and thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels are within the reference range in patients with constitutional growth delay.

Growth hormone (GH) production

Random growth hormone (GH) values are of little use because of the pulsatile fashion in which GH is secreted by the pituitary. Rather, levels of insulinlike growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and its major binding protein (IGFBP-3) are measured. They are a reliable reflection of GH production if malnutrition is not a concern. IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels are sex and age specific; they should be interpreted using skeletal age (see Radiography) rather than chronologic age. GH production is normal for bone age (biologic age) in constitutional growth delay but may appear decreased if interpreted in the context of chronologic age because of the natural increment in GH production with advancing age and pubertal stage. GH provocative testing may also yield falsely low values in some prepubertal individuals with constitutional growth delay unless they are primed with sex steroids (ie, testosterone, estrogen) 17.

Gonadotropin (luteinizing hormone [LH] and follicle-stimulating hormone [FSH]) secretion

Luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) are helpful only if the skeletal maturation is advanced to the stage consistent with puberty (ie, at least age 10 y in girls and age 12 y in boys). Low levels of these hormones are expected in young children and adolescents with younger skeletal age. This is defined as physiologic hypogonadotropic hypogonadism 18. Extremely elevated LH and FSH levels are indicative of gonadal dysfunction (ie, pathologic hypergonadotropic hypogonadism) and convey a poor prognosis for spontaneous pubertal development and future sexual function. Such levels are found in patients with Turner syndrome and in patients with Kallmann syndrome and gonadal damage from chemotherapy and irradiation.

Other

A study by Rohayem et al indicated that inhibin B and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) are useful in differentiating between boys with prepubertal constitutional delay of growth and puberty and those with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. The study found that the former had higher levels of inhibin B and anti-Müllerian hormone than did the latter 19.

A retrospective study by Varimo et al 20 suggested that in prepubertal boys, testicular volume, gonadotropin-releasing hormone–induced LH level, and basal inhibin B level are the best markers for differentiating constitutional delay of growth and puberty from congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism.

Routine laboratory studies

Abnormal routine laboratory study findings may suggest the presence of diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, renal tubular acidosis, occult malignancy, infections, and autoimmune disorders. Routine screening to rule out occult systemic disease as a cause for growth impairment or pubertal delay includes the following tests:

- Complete blood count (CBC) with differential

- Chemistries including renal and hepatic indices

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- Urinalysis

Genetic evaluation

If syndromes are suspected based on physical examination findings or family history, a karyotype or referral for genetic evaluation may be indicated. Syndromes that may mimic constitutional growth delay include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Turner syndrome (females) – Short stature and gonadal failure; abnormality of X chromosome

- Noonan syndrome – Turner phenotype but normal karyotype; often with abnormalities of pubertal development

- Kallmann syndrome – Hyposmia or anosmia and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism

- Russell-Silver syndrome – Marked growth retardation of prenatal onset

Imaging studies

Radiography

A radiographic study of the left hand and wrist to assess skeletal maturation is critical in diagnosing constitutional growth delay. Typically, the bone age begins to lag behind chronologic age during early childhood and is delayed in adolescence by an average of 2-4 years. Because the timing of puberty, the pubertal growth spurt, and epiphyseal fusion are dependent on biologic age (skeletal maturation) rather than chronologic age, all of these events are delayed in accordance with bone age. Lateral skull radiographs are rarely obtained because they are only helpful in the context of intracranial calcifications, such as those associated with craniopharyngiomas.

MRI

MRI of the pituitary gland is indicated if pituitary dysfunction is found upon hormonal evaluation or when physical symptoms (eg, visual changes, severe headaches) are present in the context of growth failure or pubertal delay.

Constitutional growth delay treatment

Constitutional delay of growth is a variation of normal growth, therefore medical treatment is not necessary other than reassurance and monitoring 2. However, short courses of sex hormones are an option for those patients experiencing psychological distress because of their delay in growth and development. In males, androgens can be used to accelerate linear growth and onset of pubertal changes. When used appropriately, no detrimental effects on adult height are evident. Therapy does not increase adult stature.

A retrospective study by Giri et al 21 indicated that in adolescent boys with constitutional delay of growth and puberty, height velocity is improved 1 year after treatment with intramuscular testosterone, although, as stated above, final predicted height is not affected by the therapy. The investigators found that at 1 year posttherapy, treated patients had a mean height velocity of 8.4 cm/year, compared with 6.1 cm/year in untreated patients.

A study by Chioma et al 22 indicated that transdermal testosterone gel and intramuscular testosterone are each effective in increasing height velocity in boys with constitutional delay of growth and puberty (as observed after 6 months). However, untreated patients were found to have a greater increase in testicular volume.

Alternatives to testosterone being investigated for boys with low predicted adult stature include oxandrolone, a weaker anabolic steroid than testosterone, and aromatase inhibitors 23. The latter are used to decrease estrogen-stimulated epiphyseal fusion, resulting in a longer period of growth 24. Guidelines have been established for children in whom growth hormone (GH) therapy is indicated 6.

The use of growth hormone (GH) therapy is actually approved for several diseases: growth hormone deficiency, renal insufficiency, Turner syndrome, Prader-Willi syndrome, Small-for-Gestational-Age (SGA), idiopathic short stature., and a few others.

Currently no guidelines about treating constitutional growth delay 16.

Follow up care

Periodic evaluation of height, weight, and stage of sexual development should be performed in children and adolescents with constitutional growth delay. Plotting of growth parameters on standard growth charts, calculation of growth velocities, and documentation of Tanner stages for genital or breast and pubic hair development should be included.

In addition to the above, adolescent males undergoing testosterone therapy should have an early morning testosterone level obtained a day or so before an injection is due when therapy may need to be discontinued. If the adolescent’s endogenous testosterone level is 150 mg/dL or greater, therapy can be stopped and pubertal development can be expected to proceed normally.

Constitutional growth delay prognosis

Excellent; children usually catch up, and growth follow the curve that correlates most of the times with their bone age 16.

Most children with constitutional growth delay attain a normal adult height; however, stature tends to be at the lower end of the reference range for that individual’s family because of the lower peak height velocity during the pubertal growth spurt. This observation may also reflect a bias in the individuals studied (more significantly delayed children referred to endocrinologists). Adult height is in contrast to individuals with idiopathic short stature, in whom stature and growth rate are likely to result in a low adult height (< 61 in for males or < 57 in for females).

Predictions for adult height can be obtained through the use of tables designed to take into consideration current height and skeletal maturation. The Bayley-Pinneau tables are most commonly used to offer predictions for adult stature from a bone age in children aged 6-7 years and older. Different tables are available for normal, early, and late maturers because differences in the tempo of puberty and peak height velocity influence growth potential. Patients and parents should be aware that these predictions are estimates that become more accurate with advancing skeletal maturation.

Constitutional growth delay is not associated with increased mortality because it is a variant of normal growth rather than a disease. However, in some affected individuals, it can be associated with significant psychological stress, resulting in poor self-image and social withdrawal. Researchers have also found that individuals with constitutional growth delay may be at increased risk for reduced bone mass in adulthood because of the delay in sex steroid influence on bone accrual during adolescence.

One compared associations between bone formation markers and resorption and bone mineral density in healthy children and in children with constitutional growth delay. The study concluded that parathyroid hormone was a valuable marker in bone mineralization during puberty and that accelerated bone mineralization was reflected by high serum parathyroid hormone levels during puberty 25.

References- Haymond M, Kappelgaard AM, Czernichow P, et al. Early recognition of growth abnormalities permitting early intervention. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102(8):787-796. doi:10.1111/apa.12266 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3738943

- Aguilar D, Castano G. Constitutional Growth Delay. [Updated 2020 Jun 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539780

- Rohani F, Alai MR, Moradi S, Amirkashani D. Evaluation of near final height in boys with constitutional delay in growth and puberty. Endocr Connect. 2018 Mar. 7 (3):456-9.

- Constitutional Growth Delay. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/919677-overview

- Rohani F, Alai MR, Moradi S, Amirkashani D. Evaluation of near final height in boys with constitutional delay in growth and puberty. Endocr Connect. 2018 Mar;7(3):456-459.

- Rogol AD, Hayden GF. Etiologies and early diagnosis of short stature and growth failure in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2014 May. 164(5 Suppl):S1-14.e6.

- Collett-Solberg PF, Jorge AAL, Boguszewski MCS, Miller BS, Choong CSY, Cohen P, Hoffman AR, Luo X, Radovick S, Saenger P. Growth hormone therapy in children; research and practice – A review. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2019 Feb;44:20-32.

- Howard SR. Genes underlying delayed puberty. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2018 Nov 15. 476:119-28.

- Barroso PS, Jorge AAL, Lerario AM, et al. Clinical and Genetic Characterization of a Constitutional Delay of Growth and Puberty Cohort. Neuroendocrinology. 2019 Nov 15.

- Hussein A, Farghaly H, Askar E, Metwalley K, Saad K, Zahran A, Othman HA. Etiological factors of short stature in children and adolescents: experience at a tertiary care hospital in Egypt. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2017 May;8(5):75-80.

- Banerjee I, Hanson D, Perveen R, Whatmore A, Black GC, Clayton PE. Constitutional delay of growth and puberty is not commonly associated with mutations in the acid labile subunit gene. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008 Apr. 158(4):473-7.

- Gravholt CH, Andersen NH, Conway GS, Dekkers OM, Geffner ME, Klein KO, Lin AE, Mauras N, Quigley CA, Rubin K, Sandberg DE, Sas TCJ, Silberbach M, Söderström-Anttila V, Stochholm K, van Alfen-van derVelden JA, Woelfle J, Backeljauw PF., International Turner Syndrome Consensus Group. Clinical practice guidelines for the care of girls and women with Turner syndrome: proceedings from the 2016 Cincinnati International Turner Syndrome Meeting. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2017 Sep;177(3):G1-G70.

- Krieger CC, Morgan SJ, Neumann S, Gershengorn MC. Thyroid Stimulating Hormone (TSH)/Insulin-like Growth Factor 1 (IGF1) Receptor Cross-talk in Human Cells. Curr Opin Endocr Metab Res. 2018 Oct;2:29-33.

- Rothermel J, Lass N, Toschke C, Reinehr T. Progressive Decline in Height Standard Deviation Scores in the First 5 Years of Life Distinguished Idiopathic Growth Hormone Deficiency from Familial Short Stature and Constitutional Delay of Growth. Horm Res Paediatr. 2016. 86 (2):117-25.

- Reinehr T, Hoffmann E, Rothermel J, Lehrian TJ, Binder G. Characteristic dynamics of height and weight in preschool boys with constitutional delay of growth and puberty or hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2019 Sep. 91 (3):424-31.

- Derraik JGB, Miles HL, Chiavaroli V, Hofman PL, Cutfield WS. Idiopathic short stature and growth hormone sensitivity in prepubertal children. Clin. Endocrinol. (Oxf). 2019 Jul;91(1):110-117.

- Gunn KC, Cutfield WS, Hofman PL, Jefferies CA, Albert BB, Gunn AJ. Constitutional delay influences the auxological response to growth hormone treatment in children with short stature and growth hormone sufficiency. Sci Rep. 2014 Aug 14. 4:6061.

- Bozzola M, Bozzola E, Montalbano C, Stamati FA, Ferrara P, Villani A. Delayed puberty versus hypogonadism: a challenge for the pediatrician. Ann Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Jun. 23 (2):57-61.

- Rohayem J, Nieschlag E, Kliesch S, Zitzmann M. Inhibin B, AMH, but not INSL3, IGF1 or DHEAS support differentiation between constitutional delay of growth and puberty and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Andrology. 2015 Sep. 3 (5):882-7.

- Varimo T, Miettinen PJ, Kansakoski J, Raivio T, Hero M. Congenital hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, functional hypogonadotropism or constitutional delay of growth and puberty? An analysis of a large patient series from a single tertiary center. Hum Reprod. 2017 Jan. 32 (1):147-53.

- Giri D, Patil P, Blair J, et al. Testosterone Therapy Improves the First Year Height Velocity in Adolescent Boys with Constitutional Delay of Growth and Puberty. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2017 Apr. 15 (2):e42311.

- Chioma L, Papucci G, Fintini D, Cappa M. Use of testosterone gel compared to intramuscular formulation for puberty induction in males with constitutional delay of growth and puberty: a preliminary study. J Endocrinol Invest. 2018 Feb. 41 (2):259-63.

- McGrath N, O’Grady MJ. Aromatase inhibitors for short stature in male children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Oct 8. 10:CD010888

- Harrington J, Palmert MR. Clinical review: Distinguishing constitutional delay of growth and puberty from isolated hypogonadotropic hypogonadism: critical appraisal of available diagnostic tests. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012 Sep. 97(9):3056-67.

- Doneray H, Orbak Z. Association between bone turnover markers and bone mineral density in puberty and constitutional delay of growth and puberty. West Indian Med J. 2008 Jan. 57(1):33-9.