Contact urticaria

Contact urticaria also called contact urticaria syndrome, is an immediate but transient localized swelling and redness that occurs on the skin after direct contact with an offending substance 1. Contact urticaria occurs within 10 to 60 minutes at the site of contact of the offending agent and completely resolves within 24 hours 2. Although contact urticaria is typically a local reaction, contact urticaria may have distant affects such as anaphylaxis 3. Contact urticaria is a form of inducible urticaria lasting less than 6 weeks. Contact urticaria can be immunological (due to allergy) or non-immunological. Contact urticaria was first cited in the literature by Alexander Fischer in 1973 2. Thereafter, Maibach and Johnson 4 defined contact urticaria syndrome in 1975. Contact urticaria should be distinguished from contact dermatitis where a dermatitis reaction develops hours to days after contact with the offending agent.

Anyone is able to get contact urticaria, however, there are some groups of people that are at increased risk for the condition to occur. Occupational groups at risk and the substances that cause contact urticaria are listed below. In most cases, exposure has occurred over time and the response is of the immunological type of contact urticaria.

- Agricultural and dairy workers: cow dander, grains and feeds

- Bakers: ammonia persulfate, flour, alpha-amylase

- Dental workers: latex, acrylate and epoxy resins, toothpaste

- Electronic workers: acrylate and latex

- Food workers: foodstuffs, such as cheese, egg, milk, fish, shellfish, fruit, flour, wheat

- Hairdressers: ammonia persulfate, latex

- Medical/veterinary workers: latex

Food handlers can develop contact urticaria in response to vegetables, raw meats, and fish and shellfish 5. Important to note is that causative agents may be airborne (eg, in a manufacturing facility, plant/animal dander exposure). For example, some caterpillars (eg, Thaumetopoea pityocampa) have fine hairs that can become scattered and airborne, leading to exposure among forestry workers and recreational visitors to endemic areas, including children 6. Affected personnel in one study included pinecone or resin collectors, woodcutters, farmers, and stockbreeders 7. The mechanism is an immunologic contact urticaria that can lead to severe reactions; in one cohort of 16 patients, 80% had angioedema and 14% had severe anaphylaxis. Wheals were seen primarily on the neck and forearms 8.

The risk for developing contact urticaria increases when there is an interruption of the stratum corneum due to filaggrin gene mutations or skin irritants 2. The occupations at the most risk of developing contact urticaria are healthcare, lab work, agriculture, hairdressers, cosmetic industry, chemical industry, cleaning, construction, catering, cooking, electronics, machinery, and metal products 9.

The prevalence of contact urticaria in the general population is unrecognized due to lower disease diagnosis rates. The prevalence of occupational contact urticaria is 0.4% and accounts for 30% of all occupational skin diseases 2. Research indicates a prevalence of 5% to 10% for latex-related contact urticaria 10. The prevalence of sensitization to natural rubber latex among healthcare workers is between 5% to 13% 11. Natural rubber latex, cosmetics, skin creams, and sorbic acid are some of the most common causative agents identified 12. The Finnish Registry 13 indicated that the incidence of contact urticaria has more than doubled between 1989 and 1994 with cow dander, natural rubber latex, flour, and grains as common triggers.

Figure 1. Contact urticaria

Contact urticaria causes

Contact urticaria is caused by a variety of compounds, such as foods, preservatives, fragrances, plant and animal products, metals, and rubber latex. The mechanism by which these provoke an immediate urticarial rash at the area of contact can be divided into three categories: non-immunological contact urticaria such as nettle rash, immunological (allergic) contact urticaria for example, food, latex, plants or animal hair or fur and contact urticaria due to unknown mechanisms 2.

- Non-immunological contact urticaria typically causes mild localized reactions that clear within hours, for example, stinging nettle rash. This type of urticaria occurs without prior exposure to a patient’s immune system to an allergen.

- Immunological contact urticaria occurs most commonly in atopic individuals (people who are prone to allergy). Hence prior exposure to an allergen is required for this type of contact urticaria to occur.

- Contact urticaria due to an unknown mechanism

Commonly reported causes of the different types of contact urticaria are shown below.

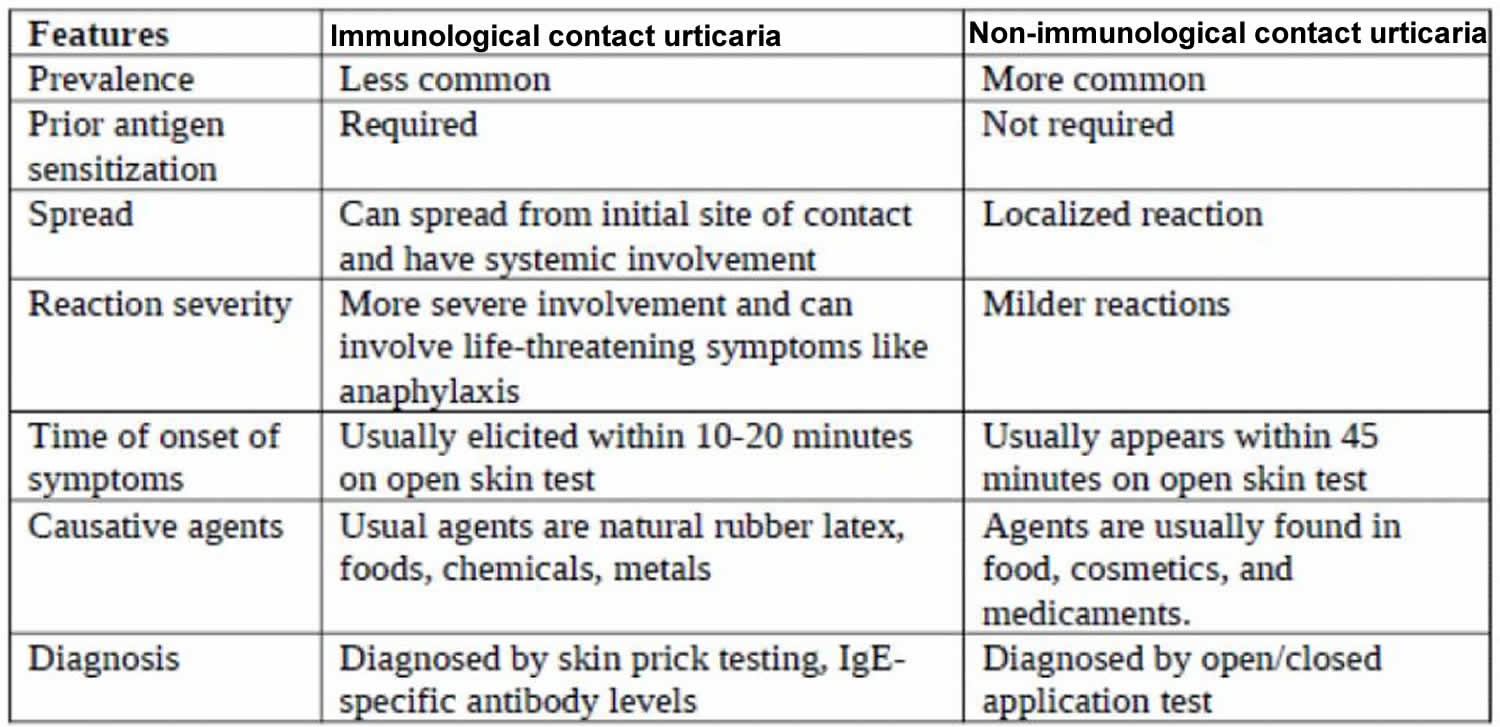

Table 1. Contact urticaria types

Non-immunologic contact urticaria

Non-immunologic contact urticaria agents can be divided into the following seven categories:

- Animals (e.g., arthropods, caterpillars, corals)

- Foods (e.g., pepper, mustard, thyme)

- Fragrances and flavorings (e.g., balsam of Peru, cinnamic acid, cinnamic aldehyde)

- Medications (e.g., benzocaine, camphor, witch-hazel)

- Metals (e.g., cobalt)

- Plants (e.g., nettles, seaweed)

- Preservatives and disinfectants (e.g., benzoic acid, formaldehyde)

Some commonly reported causes of non-immunologic contact urticaria include the following 14:

- Ingredients of cosmetics and medicaments

- Sorbic acid, a commonly used preservative in many foods

- Raw meat, fish, and vegetables

- Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)

- Cobalt chloride

- Tetrahydrofurfuryl nicotinate (Trafuril, Ciba Laboratories)

- Polyaminopropyl biguanide (eg, in wet wipes) 17

- Animal hair (eg, ferrets) 18

Non-immunologic contact urticaria is less severe and more common than immunologic contact urticaria. In some patients, nonimmunologic contact urticaria may account for cosmetic intolerance syndrome 19. There are no specific antibodies against the causative agents. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) inhibit the response showing that prostaglandins (e.g., prostaglandin D2) may play a role in the pathogenesis 20. Histamine has not shown to play a role since antihistamines did not have any inhibitory effect. Other proposed mechanisms include direct capillary damage at the site of contact leading to the non-IgE mediated release of vasoactive amines, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and acetylcholine 21. Unlike immunologic contact urticaria, there are no systemic manifestations, and the reaction remains localized. Prior exposure to the antigen is not necessary, and it can present on initial skin contact with the allergen. The symptoms vary depending on the site of exposure, the concentration of the substance, and the mode of exposure 22.

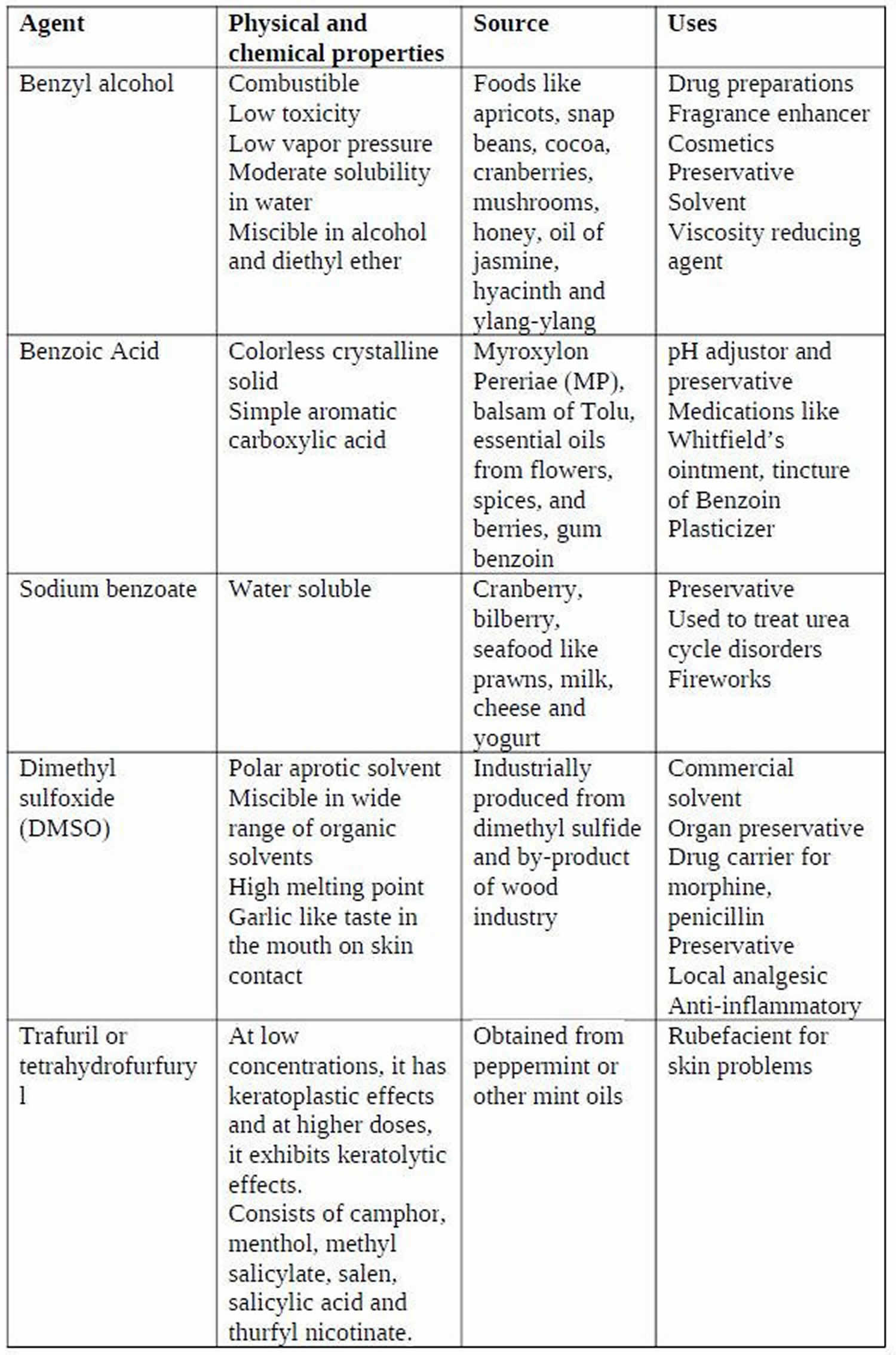

Described in Table 2 are some of the common causative agents for non-immunologic contact urticaria. There is an overlap in the causative agents between immunologic contact urticaria and non-immunologic contact urticaria.

Table 2. Common causative agents for non-immunologic contact urticaria

Immunologic contact urticaria

The agents causing immunologic contact urticaria can divide into the following four categories 23.

- Group 1 – Plant-derived proteins (e.g., vegetables, fruits, spices)

- Group 2– Animal-derived proteins (e.g., meat, dairy products, seafood)

- Group 3– Grains (e.g., wheat, barley, rye)

- Group 4– Enzymes (e.g., alpha-amylase, cellulase, xylanase)

Reported causes of immunologic contact urticaria include the following 24:

- Natural rubber latex (eg, surgical gloves, found in urinary catheters)

- Raw meat, fish, and vegetables

- Potatoes

- Phenylmercuric propionate

- Hair dye (eg, at a hairdresser) 25

- Grass

- Animals

- Many antibiotics

- Some metal, e.g. nickel

- Parabens

- Benzoic and salicylic acids

- Polyethylene glycol

- Short chain alcohols

There are two broad categories of agents causing immunologic contact urticaria 26.

- High molecular weight proteins with molecular weight more than 10000 kD. Ex. dietary proteins.

- Hapten chemicals with molecular weight less than 1000 kD: They conjugate with carrier proteins like albumin and form the hapten-carrier protein complex. Ex. Di-isocyanate used in polyurethane products and ammonium persulphate.

Immunologic contact urticaria involves antigen binding to IgE-specific antibodies (type 1 hypersensitivity reaction) on the dermal mast cells. After antigen-antibody binding, there is a release of histamine and vasoactive mediators like prostaglandins and leukotrienes, resulting in disturbance of skin microcirculation. A stronger allergic response than non-immunologic contact urticaria gets elicited due to the ready absorption of the proteins by the skin 27. Prior sensitization to the agent is necessary for the reaction to develop. Repeated exposure to the antigen can lead to progressive worsening of symptoms. Concomitant history of other atopic disorders like personal or family history of asthma, eczema, and hay fever is a risk factor 26. The reaction spreads beyond the site of initial contact and progresses to generalized urticaria, even leading to anaphylactic shock. This progression of symptoms in a step-wise manner has been described in four stages as “contact urticaria syndrome”.

- Stage 1– Localized urticaria (redness and swelling), dermatitis and some non-specific symptoms like burning, itching, tingling, etc

- Stage 2– Generalized urticaria

- Stage 3– Systemic manifestations like bronchial asthma, angioedema, rhinitis, conjunctivitis, oropharyngeal symptoms (Ex. lip swelling, hoarseness, difficulty in swallowing), gastrointestinal symptoms (Ex.nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal cramps)

- Stage 4– Generalized anaphylactic reaction including anaphylactic shock.

Contact urticaria due to an unknown mechanism

Some reactions of contact urticaria have unknown mechanisms that remain unclassified. Ammonium persulphate is a classic example of this type of response. Contact urticaria due to ammonium persulphate can be mediated by type 1 (IgE-mediated) or by classical pathway (IgG or IgM-mediated).

Protein contact dermatitis

Protein contact dermatitis was first described in kitchen workers who had localized dermatitis of the hands and forearm. Protein contact dermatitis is chronic hand eczema that occurs in contact with proteins, with or without a positive prick test 28. The pathophysiology involves repeated microtrauma to the skin, leading to the penetration of the large protein molecules. It involves a type 1, type 4, or a delayed phase-type 1 hypersensitivity reaction. The reaction occurs within minutes of contact, but only 15% reported an immediate-type hypersensitivity reaction 28. Those who react to specific dietary proteins rarely present with systemic symptoms on oral ingestion 29. The proteins can spread from the hands to the sites of contact, including the face or abdomen 29.

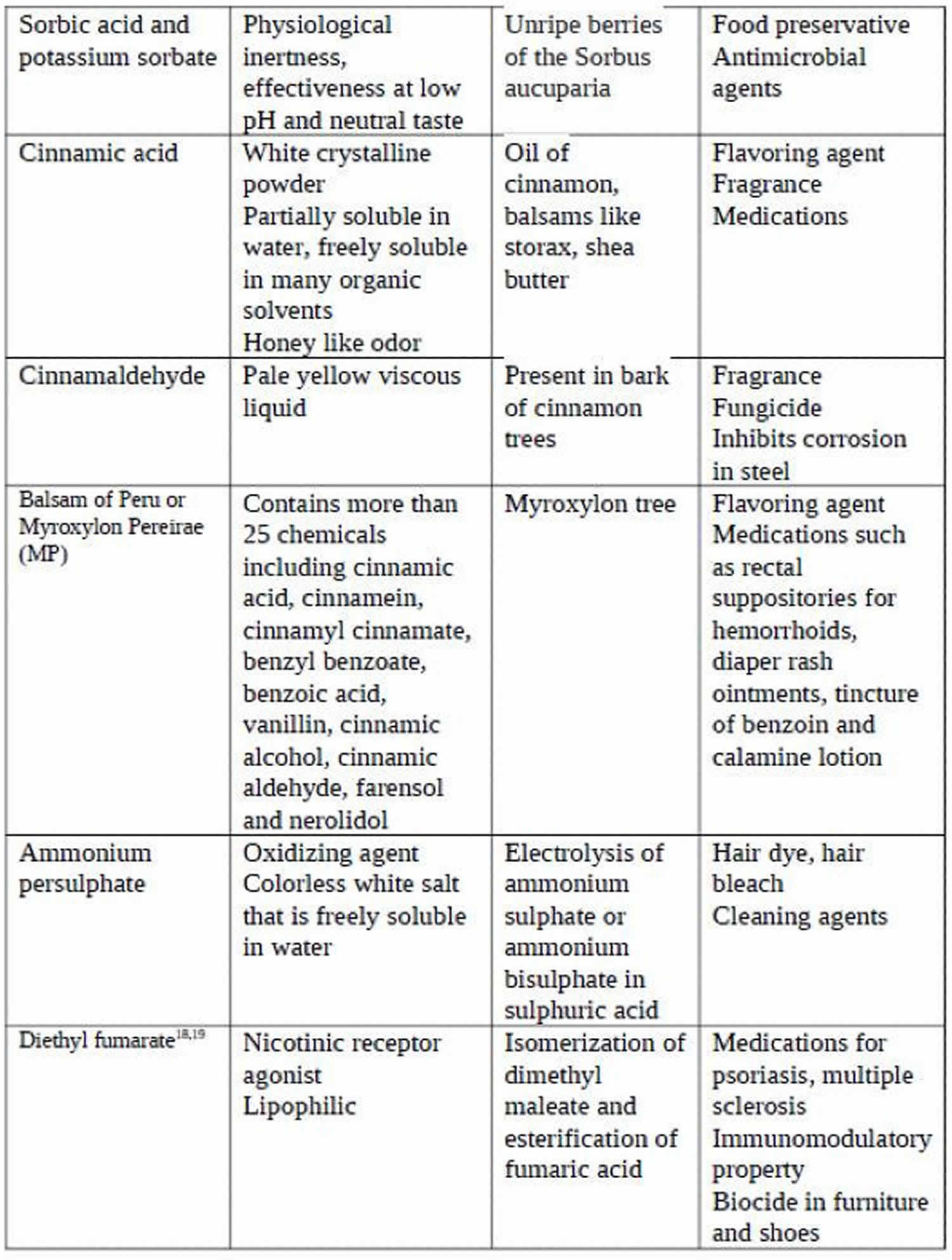

Table 3. Common causative agents in protein contact dermatitis

Contact urticaria signs and symptoms

Contact urticaria reactions appear within minutes to about one hour after exposure of the offending substance to the skin. Signs and symptoms of affected skin areas include:

- Local burning sensation, tingling or itching

- Localized or generalized red swellings or weals may occur, especially on the hands. The severity of redness and swelling can range from slight redness or spots with minimal swelling to fiery redness with tense swelling and weals.

- Rash usually resolves by itself within 24 hours of onset.

Signs and symptoms may occur in other organs other than the skin. These are known as extracutaneous reactions and are more likely to occur in patients with immunological contact urticaria.

Features of extracutaneous reactions include:

- Wheezing (bronchial asthma)

- A runny nose, watery eyes

- Lip swelling, hoarse throat, difficulty swallowing

- Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, cramps

- Severe anaphylactic shock (this can be life-threatening).

Contact urticaria complications

Immunologic contact urticaria has the potential to lead to life-threatening symptoms like anaphylaxis; hence, it is important to diagnose and manage these patients appropriately. Other complications include the risk of secondary bacterial infection from skin breakdown from repeated scratching.

Contact urticaria diagnosis

Sometimes it is easy to recognize contact urticaria and no specific tests are necessary. Radioallergosorbent tests (RAST) (specific IgE blood test) where available, can be used to confirm the allergy. Skin prick test and scratch patch tests confirm the diagnosis of contact urticaria but do not differentiate between allergic and non-allergic mechanisms.

Clinical history

In addition to general history-taking, the clinician should focus particular attention on the history of exposure to potential causative agents in food, home/work environment, cosmetics, and personal care products. Temporal relationship from the time of exposure to the development of symptoms and time for resolution of symptoms is necessary information. Also include aggravating factors (i.e., temperature changes, physical pressure, etc.) and relieving factors like medications in history. Obtain details on the specific skin symptoms (e.g. wheals, tingling, burning, itching) and progression of symptoms. A personal and family history of atopy helps make the diagnosis of IgE-mediated immunologic contact urticaria. Volatile proteins can cause signs and symptoms of conjunctivitis, rhinitis, or asthma when they come in contact with the mucosa of the conjunctiva or respiratory tract (e.g. flour). Other systemic symptoms like abdominal pain, itching in the mouth on oral ingestion (oral allergy syndrome), and diarrhea may develop in contact with the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract.

Physical examination

Clinical presentation is commonly a wheal and flare response and urticarial swelling. Patients affected by contact urticaria can present with hives (urticaria) or dermatitis (eczema). The urticarial response appears as an erythematous swelling with surrounding pallor. In a non-immunologic contact urticaria reaction, the typical wheal and flare response may be absent. The skin examination should focus on the site of involvement, the pattern of distribution, size, shape, and confluency of lesions, angioedema, erythema, pallor, dermographism, and urticarial vasculitis. Contact urticaria wheals do not blister, and scaling is generally not seen. They remain transient without any residual skin changes or pigmentation 30. The diagnostic signs are different during an active flare vs. a period of quiescence.

Protein contact dermatitis presents as recurrent dermatitis with urticarial plaques or vesicles. The vesicles can develop rapidly and progress to erythematous-squamous or erythematous-vesicular lesions 31. Paronychia with periungual edema and erythema can be a sign of protein contact dermatitis 32.

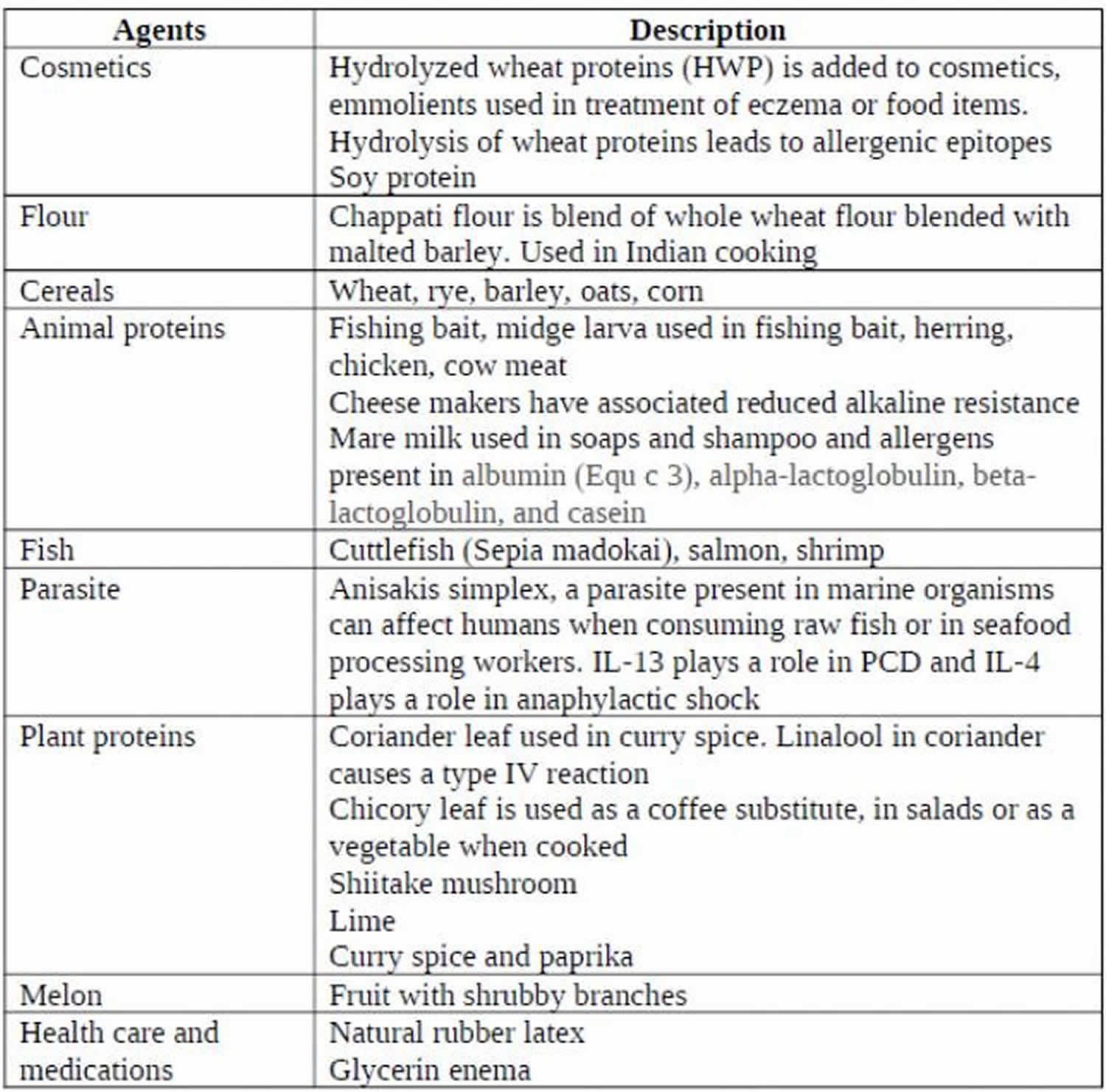

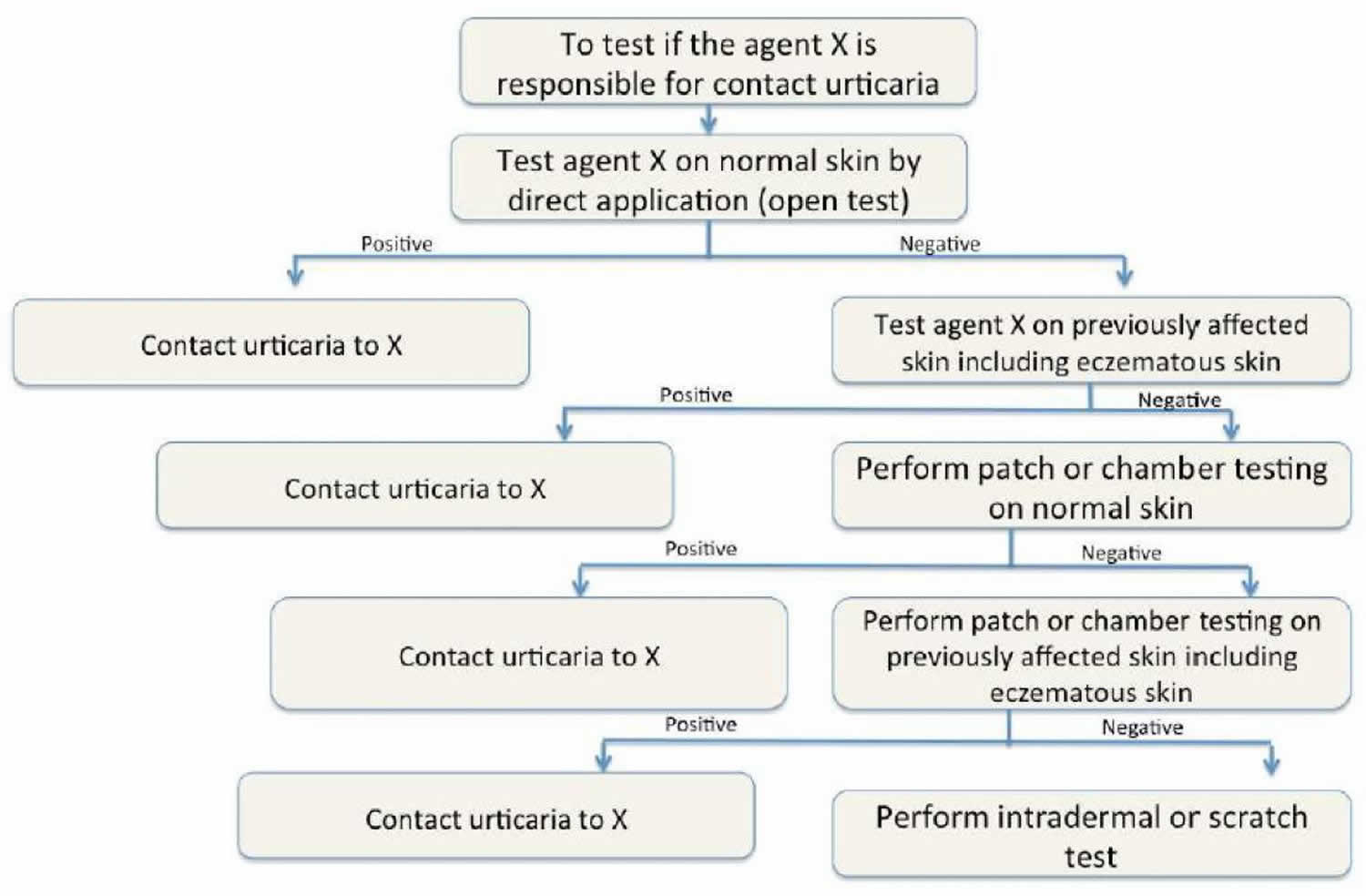

Figure 2. Contact urticaria diagnostic algorithm

In-vivo test

In-vivo tests are most common for the diagnosis of contact urticaria. Clinical supervision with the provision to handle an impending anaphylactic shock is necessary. Both immunologic contact urticaria and non-immunologic contact urticaria reactions occur within 15 to 20 minutes or can be delayed. If testing on intact skin is negative, then previously affected skin sites are used. Positive test results require careful correlation with clinical symptoms. Medications like antihistamines, NSAIDs, and exposure to ultra-violet light can cause false-negative results. The patient should be off antihistamines for 48 hours before testing. See figure 1 for the diagnostic algorithm to test for immediate contact reactions 11.

- Prick test: It is considered the test of choice for the diagnosis of immunologic contact urticaria. The inner aspect of the forearm is the preferred site, and multiple allergens can undergo testing simultaneously, using positive control with histamine and negative control with normal saline with results interpreted in 30 minutes. False-positive results occur due to a positive reaction from one test site spreading to the neighboring site or irritant reaction. Protein contact dermatitis is diagnosable with the prick test. If skin prick tests and serum allergen-specific IgE tests are negative, a provocation or direct challenge test may be needed.

- Open test or skin provocation test: The open test is used for the diagnosis of non-immunologic contact urticaria. The test consists of gently rubbing 0.1ml of the test substance over a 3 cm x 3 cm area of intact skin on the volar aspect of the forearm. The site requires an examination at 20, 40, and 60 minutes. The best vehicle for testing the agents is an alcohol-water or alcohol propylene glycol mixture.

- Use test: The test agent in the same vehicle of delivery is used to observe for the reaction. The serial incremental dosing of the agent is. The usual sites of skin testing are the upper back, flexor aspect of the upper arm, and forearm.

- Chamber or patch test: The test substance is applied to small aluminum containers for 15 minutes and attached to the skin via porous tape. The results are recorded at 20, 40, and 60 minutes for an immediate reaction. A delayed-type response gets assessed at 48 to 96 hours after patch application to the back. The sensitivity of this test is higher due to increased absorption by the skin. A smaller area of skin is used than the open test. A false-positive response called ‘angry back’ due to active dermatitis is noted in some. A patch test is not routinely recommended because many common allergens may cause a false positive response (e.g. balsam of Peru, paraben, sorbic acid, formaldehyde, cinnamaldehyde, etc.).

- Scratch test: A deep dermal scratch with the test substance is performed using the blunt bottom of a lancet after the allergen is applied to the skin; this is useful for diagnosing contact urticaria to non-standard allergens 33. Due to the risk of anaphylaxis, it should always take place under medical supervision.

- Intradermal testing: The test uncommon due to the risk of anaphylaxis. When testing with non-standardized substances, the test controls should be assessed on at least 20 people to rule out false-positive results.

- Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) test: The dimethylsulfoxide test is fast, reliable, and used to test the integrity of the skin barrier function. A wheal response occurs on the application of dimethylsulfoxide to the skin in susceptible individuals. A clinical grading is available to quantify the response (0 = no reaction, 1 = follicular wheal, 2 = slight elevated solid wheal, 3 = elevated solid, tense wheal).

In-vitro test

For the diagnosis of immunologic contact urticaria, the presence of IgE-specific antibodies against the causative agent is used 27. Based on the patient’s history, lab workup typically includes complete blood count (CBC), blood culture, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), basic metabolic panel (BMP), thyroid auto-antibodies, anti-nuclear antibody level (ANA) and complement levels (C3, C4) to rule out differential diagnosis like systemic illness, chronic idiopathic urticaria, autoimmune diseases, infection, etc 34.

Contact urticaria treatment

Avoidance of the offending substance is the cornerstone of management. The main aim of treatment is to avoid the substances that cause the urticarial reaction and find suitable alternatives. Gloves may be used to protect hands from contact with materials of concern, but avoid rubber gloves if allergic to latex. Protective gear like gloves, skin conditioning creams or emollients, and cotton liners are necessary when the exposure at work is unavoidable 35. In most cases, the rash rapidly clears up completely once the offending substance is no longer in contact with the skin.

Patients should have an understanding of the nature of their urticarial reaction (non-immunological versus immunological). Patients with immunological contact urticaria should wear medical alert tags and be aware of the potential life-threatening reactions of the condition.

For patients with allergy to natural rubber latex, alternatives such as nitrile, neoprene, and polyvinyl chloride gloves are recommended. Some of the healthcare institutions around the world have banned powdered natural rubber latex gloves at work resulting in the decline of incidence of contact urticaria 36. For patients with contact urticaria to natural rubber latex, avoidance of all latex-containing products is recommended.

Medications that may be used to minimize the reaction include antihistamines and adrenaline for more severe reactions. Second-generation H1-receptor blockers (e.g., diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, loratadine, desloratadine) are the first-line treatment in Icontact urticaria. Leukotriene inhibitors like montelukast, zafirlukast, and zileuton inhibit the inflammatory component 37.

Aspirin and NSAIDs are the first-line treatment options for the management of non-immunological contact urticaria.

Self-administered subcutaneous epinephrine pens should be available at all times to the patient.

Steroids are second-line treatment options and help to prevent the delayed phase of an anaphylactic reaction.

Immunosuppressive drugs like cyclosporine and methotrexate are options in severe cases.

Ultraviolet A and B light inhibit non-immunological contact urticaria reaction, and the effect can last for up to 2 weeks after treatment. It has the advantage of inhibiting skin sites that are not directly irradiated 38.

Subcutaneous immunotherapy in the management of contact urticaria is an object of research. A study on 41 bakers sensitized to wheat protein who received subcutaneous immunotherapy, has shown promise as an intervention in the management of contact urticaria 39. Immunotherapy with standardized latex extract in workers sensitized to natural rubber latex has shown improvement in the skin reactivity 40.

A rush (2 or 4-day) sublingual desensitization to natural rubber latex has shown significant improvement in symptom scores 41.

Contact urticaria prognosis

The prognosis in contact urticaria syndrome is entirely dependent on the ability of the patient to avoid etiologic substances. However, even in cases of severe immunologic contact urticaria to latex, the long-term prognosis can be good if patients take an active role in controlling their environment by educating themselves and others and by taking proper precautions.

Most of the patients affected by contact urticaria experience relief of symptoms with avoidance of triggers and medications. The disease duration is shorter for infants and children and prolonged when associated with other atopic diseases or with other systemic manifestations as seen in immunological contact urticaria 34. Repeated exposure to the same agents may lead to a progressively severe response in immunologic contact urticaria.

A delayed (48-72 hours) allergic eczematous contact dermatitis can result from some compounds that produce immunologic contact urticaria and, to a lesser extent, from compounds that produce the nonimmunologic form. When this occurs in occupational contact urticaria syndrome, debilitating hand dermatitis may ensue. If immediate contact reactions are not specifically sought, routine patch testing may miss the diagnosis.

Immunologic contact urticaria can also extend extracutaneously. In a study of 70 German patients with contact urticaria, 51% had rhinitis, 44% had conjunctivitis, 31% had dyspnea, 24% had systemic symptoms, and 6% had severe systemic reactions during surgery. Extracutaneous contact urticaria syndrome has led to anaphylaxis in severe cases and is believed to be a cause of death intraoperatively in some cases (due to allergy to latex). In fact, topical antibiotics such as bacitracin have also been associated with anaphylactic reactions 42.

References- Contact urticaria. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/contact-urticaria

- Vethachalam S, Persaud Y. Contact Urticaria. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK549890

- Bolognia J, Schaffer J, Cerroni L. Urticaria and Angioedema. Dermatology. 4th Ed. Elsevier; 2017. Vol 1: 311.

- Maibach HI, Johnson HL. Contact urticaria syndrome. Contact urticaria to diethyltoluamide (immediate-type hypersensitivity). Arch Dermatol. 1975 Jun. 111(6):726-30.

- James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin. 11th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2011.

- Garty BZ, Danon YL. Processionary caterpillar dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1985 Mar. 2(3):194-6.

- Vega J, Vega JM, Moneo I, Armentia A, Caballero ML, Miranda A. Occupational immunologic contact urticaria from pine processionary caterpillar (Thaumetopoea pityocampa): experience in 30 cases. Contact Dermatitis. 2004 Feb. 50(2):60-4.

- Vega JM, Moneo I, Armentia A, Vega J, De la Fuente R, Fernandez A. Pine processionary caterpillar as a new cause of immunologic contact urticaria. Contact Dermatitis. 2000 Sep. 43(3):129-32.

- Orb Q, Millsop JW, Harris K, Powell D. Prevalence and interest in the practice of scratch testing for contact urticaria: a survey of the American contact dermatitis society members. Dermatitis. 2014 Nov-Dec;25(6):366-9.

- Doutre MS. Occupational contact urticaria and protein contact dermatitis. Eur J Dermatol. 2005 Nov-Dec;15(6):419-24.

- Gimenez-Arnau A, Maurer M, De La Cuadra J, Maibach H. Immediate contact skin reactions, an update of Contact Urticaria, Contact Urticaria Syndrome and Protein Contact Dermatitis — “A Never Ending Story”. Eur J Dermatol. 2010 Sep-Oct;20(5):552-62. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2010.1049

- Süß H, Dölle-Bierke S, Geier J, Kreft B, Oppel E, Pföhler C, Skudlik C, Worm M, Mahler V. Contact urticaria: Frequency, elicitors and cofactors in three cohorts (Information Network of Departments of Dermatology; Network of Anaphylaxis; and Department of Dermatology, University Hospital Erlangen, Germany). Contact Dermatitis. 2019 Nov;81(5):341-353. doi: 10.1111/cod.13331 https://doi.org/10.1111/cod.13331

- Kanerva L, Toikkanen J, Jolanki R, Estlander T. Statistical data on occupational contact urticaria. Contact Dermatitis. 1996 Oct;35(4):229-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02363.x

- Suzuki R, Fukuyama K, Miyazaki Y, Namiki T. Contact urticaria syndrome and protein contact dermatitis caused by glycerin enema. JAAD Case Rep. 2016 Mar 3. 2 (2):108-10.

- Saito M, Nakada T. Contact urticaria syndrome from eye drops: levofloxacin hydrate ophthalmic solution. J Dermatol. 2013 Feb. 40(2):130-1.

- Gandolfo-Cano M, Bartra J, González-Mancebo E, Feo-Brito F, Gómez E, Bartolomé B, et al. Molecular characterization of contact urticaria in patients with melon allergy. Br J Dermatol. 2014 Mar. 170(3):651-6.

- Creytens K, Goossens A, Faber M, Ebo D, Aerts O. Contact urticaria syndrome caused by polyaminopropyl biguanide in wipes for intimate hygiene. Contact Dermatitis. 2014 Nov. 71(5):307-9.

- Amsler E, Bayrou O, Pecquet C, Francès C. Five cases of contact dermatitis to a trendy pet. Dermatology. 2012. 224(4):292-4.

- Verhulst L, Goossens A. Cosmetic components causing contact urticaria: a review and update. Contact Dermatitis. 2016 Dec. 75 (6):333-344.

- McFadden J. Immunologic contact urticaria. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2014 Feb;34(1):157-67. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2013.09.005

- Davari P, Maibach HI. Contact urticaria to cosmetic and industrial dyes. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2011 Jan;36(1):1-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2010.03854.x

- Zhai H, Zheng Y, Fautz R, Fuchs A, Maibach HI. Reactions of non-immunologic contact urticaria on scalp, face, and back. Skin Res Technol. 2012 Nov;18(4):436-41. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2011.00590.x

- Amaro C, Goossens A. Immunological occupational contact urticaria and contact dermatitis from proteins: a review. Contact Dermatitis. 2008 Feb;58(2):67-75. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2007.01267.x

- Spoerl D, Scherer K, Bircher AJ. Contact urticaria with systemic symptoms due to hexylene glycol in a topical corticosteroid: case report and review of hypersensitivity to glycols. Dermatology. 2010. 220(3):238-42.

- Vanden Broecke K, Bruze M, Persson L, Deroo H, Goossens A. Contact urticaria syndrome caused by direct hair dyes in a hairdresser. Contact Dermatitis. 2014 Aug. 71(2):124-6.

- Wang CY, Maibach HI. Immunologic contact urticaria–the human touch. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2013 Jun;32(2):154-60. doi: 10.3109/15569527.2012.727519

- Harvell J, Bason M, Maibach HI. Contact urticaria (immediate reaction syndrome). Clin Rev Allergy. 1992 Winter;10(4):303-23.

- Vester L, Thyssen JP, Menné T, Johansen JD. Occupational food-related hand dermatoses seen over a 10-year period. Contact Dermatitis. 2012 May;66(5):264-70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0536.2011.02048.x

- Barbaud A, Poreaux C, Penven E, Waton J. Occupational protein contact dermatitis. Eur J Dermatol. 2015 Nov-Dec;25(6):527-34. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2015.2593

- Giménez-Arnau A. Contact urticaria and the environment. Rev Environ Health. 2014;29(3):207-15. doi: 10.1515/reveh-2014-0042

- Lynde C, Guenther L, Diepgen TL, Sasseville D, Poulin Y, Gulliver W, Agner T, Barber K, Bissonnette R, Ho V, Shear NH, Toole J. Canadian hand dermatitis management guidelines. J Cutan Med Surg. 2010 Nov-Dec;14(6):267-84. doi: 10.2310/7750.2010.09094

- Kanerva L. Occupational protein contact dermatitis and paronychia from natural rubber latex. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000 Nov;14(6):504-6. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00175.x

- Bhatia R, Alikhan A, Maibach HI. Contact urticaria: present scenario. Indian J Dermatol. 2009 Jul;54(3):264-8.

- Sabroe RA. Acute urticaria. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2014 Feb;34(1):11-21. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2013.07.010

- Adisesh A, Robinson E, Nicholson PJ, Sen D, Wilkinson M., Standards of Care Working Group. U.K. standards of care for occupational contact dermatitis and occupational contact urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 2013 Jun;168(6):1167-75.

- Bensefa-Colas L, Telle-Lamberton M, Faye S, Bourrain JL, Crépy MN, Lasfargues G, Choudat D, RNV3P members. Momas I. Occupational contact urticaria: lessons from the French National Network for Occupational Disease Vigilance and Prevention (RNV3P). Br J Dermatol. 2015 Dec;173(6):1453-61.

- Bhatia R, Alikhan A, Maibach HI. Contact urticaria: present scenario. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54(3):264-268. doi:10.4103/0019-5154.55639

- Larmi E. PUVA treatment inhibits nonimmunologic immediate contact reactions to benzoic acid and methyl nicotinate. Int J Dermatol. 1989 Nov;28(9):609-11. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1989.tb02540.x

- Cirla AM, Lorenzini RA, Cirla PE. Recupero professionale di panificatori allergici mediante vaccino verso farina di frumento [Specific immunotherapy and relocation in occupational allergic bakers]. G Ital Med Lav Ergon. 2007 Jul-Sep;29(3 Suppl):443-5. Italian

- Sastre J, Fernández-Nieto M, Rico P, Martín S, Barber D, Cuesta J, de las Heras M, Quirce S. Specific immunotherapy with a standardized latex extract in allergic workers: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003 May;111(5):985-94. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.1390

- Tabar AI, Gómez B, Arroabarren E, Rodríguez M, Lázaro I, Anda M. Perspectivas de tratamiento de la alergia al látex: inmunoterapia [Perspectives in the treatment of allergy to latex: immunotherapy]. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2003;26 Suppl 2:97-102. Spanish.

- Cronin H, Mowad C. Anaphylactic reaction to bacitracin ointment. Cutis. 2009 Mar. 83(3):127-9.