What is cracked tooth syndrome

Cracked tooth syndrome may be defined as a tooth fracture plane of unknown depth, which originate from the crown, passes through the tooth structure involving the dentine and occasionally extends into the pulp and extends subgingivally, and may progress to connect with the pulp space and/or periodontal ligament 1. Cracked tooth syndrome presents mainly in patients aged between 30 years and 50 years 2. Men and women are equally affected 3. Mandibular second molars, followed by mandibular first molars and maxillary premolars, are the most commonly affected teeth 4. While the crack tends to have a mesiodistal orientation in most teeth, it may run buccolingually in mandibular molars 3.

Two classic patterns of crack formation exist 5. The first occurs when the crack is centrally located, and following the dentinal tubules may extend to the pulp; the second is where the crack is more peripherally directed and may result in cuspal fracture. Pressure applied to the crown of a cracked tooth leads to separation of the tooth components along the line of the crack. Such separation in dentine results in the movement of fluid in the dentinal tubules,stimulating odontoblasts in the pulp as well as the stretching and rupturing odontoblastic processes lying in the tubules,3thus stimulating pulpal nociceptors. Ingress of saliva along the crack line may further increase the sensitivity of dentine 6. Direct stimulation of pulpal tissues occurs if the crack extends into the pulp.

Cracked tooth syndrome is probably one of the hardest dental condition to diagnose. This is because of the fact that the patient often finds it hard to point out where exactly the pain is coming from, hence the difficulty of the dental professional to make a definitive diagnosis. In order to pinpoint the problem, your dentist will need to make thorough examination of the area where the pain is coming from.

Even with X-rays, these are hard to find since these cracks are usually too fine to be seen on these. Sometimes, these are also hard to locate due to their being found underneath a person’s gums. If this is left untreated, the damage to the person’s tooth will progress to bigger and oftentimes more painful dental problems. These often happen in the lower back areas of your mouth, where the lower molars can be found. These cracks happen due to a number of reasons, such as constant clenching or grinding, or even due to the habit of chewing ice. These cracks can also appear due to accidents like biting into something hard unexpectedly (a bone or a pit) or because of a recent trauma. Whatever the case may be, these can and do occur, and if left unchecked, can result in a broken tooth, infection, and even more pain.

The most common tip dentists give patients who suffer from these cracks is, in order to avoid or prevent more of these from happening, they will need to rid themselves of such habits as chewing ice, clenching and grinding. They will also be advised to try and be careful when eating or chewing since biting down on hard substances that are in food can also crack a person’s tooth.

Treatments for cracked tooth syndrome are not guaranteed to solve it or relieve the person of it. Treatments will also depend on where the cracks can be found, how deep these are, and how large such cracks are. Some of the more common treatments include the use of crowns on such teeth, and root canals. You may also find your dentist removing such a tooth, if the damage is too extensive, and they may also suggest an implant to replace the missing tooth.

If you suspect that you have cracks in your teeth, you should consult with your dentist as soon as possible to prevent the worsening of such a problem. Pain when you chew or when you bite are indicators of such a dental issue. If you are constantly grinding and clenching your teeth, having your dentist check your teeth for cracks is also a must.

Cracked tooth syndrome causes

Causes of cracked tooth syndrome:

- Natural wear: Over the years, the repetitive everyday use of the teeth for biting and chewing may cause cracks on teeth.

- Clenching or grinding teeth (bruxism) is one of the major causes of fractured tooth syndrome. Grinding and clenching puts teeth under excessive pressure making them more susceptible to cracks.

- Bad chewing habits such as biting pencils or chewing on hard foods.

- Trauma to the mouth.

- Large fillings can weaken the teeth resulting in tooth fracture.

- Untreated extensive tooth decay.

- Complications during/after endodontic therapy. Sometimes the pressure applied on a tooth during root canal treatment may cause a crack. After a root canal treatment teeth become brittle and they are more susceptible to cracked tooth syndrome.

Restorative procedures

- Inadequate design features

- Over-preparation of cavities

- Insufficient cuspal protection in inlay/onlay design

- Deep cusp–fossa relationship

- Stress concentration

- Pin placement

- Hydraulic pressure during seating of tightly fitting cast restorations

- Physical forces during placement of restoration, e.g., amalgam or soft gold inlays (historical)

- Non-incremental placement of composite restorations (tensile stress on cavity walls)

- Torque on abutments of long-span bridges

Occlusal

- Masticatory accident: Sudden and excessive biting force on a piece of bone

- Damaging horizontal forces: Eccentric contacts and interferences (especially mandibular second molars)

- Functional forces:

- Large untreated carious lesions

- Cyclic forces

- Parafunction: Bruxism

Developmental

- Incomplete fusion of areas: Occurrence of cracked tooth syndrome in unrestored teeth of calcification

Miscellaneous

- Thermal cycling: Enamel cracks

- Foreign body: Lingual barbell

- Dental instruments: Cracking and crazing associated with high-speed handpieces

Historically, cracked tooth syndrome was associated with the placement of“soft gold” inlays (Class I Gold) that were physically adapted to the cavity using a mallet 7. Nowadays, common causes include masticatory accidents, such as biting on a hard, rigid object with unusually high force 8 or excessive removal of tooth structure during cavity preparation 9. Parafunctional habits such as bruxism are also associated with the development of cracked tooth syndrome 10.

Commonly, the tooth has been structurally compromised by removal of tooth substance during restorative procedures 9. Occlusal contact occurring on extensive occlusal or proximo-occlusal intracoronal restorations (either cast metal or plastic restorations) subject the remaining weakened tooth structure to lateral masticatory forces, particularly during chewing 3. Such cyclic forces result in the establishment and propagation of cracks 3. Deep cusp–fossa relationships due to over-carving of restorations 11 or cast restorations placed without proper consideration for cuspal protection 3, also render the tooth vulnerable. Cameron describes a case where he fitted a gold inlay on a molar tooth that subsequently developed symptoms of cracked tooth syndrome. The patient complained of pain on application of pressure to the tooth. Having repeatedly performed occlusal adjustments over a one year period, complete relief of symptoms did not occur until a distal cusp fractured off the tooth 5.

Excessive condensation pressures, expansion of certain poorer quality amalgam alloys when contaminated with moisture, placement of retentive pins 8 and extensive composite restorations placed without due care for incremental technique (resulting in tensile forces in the tooth structure due to polymerization contraction) predispose to fracture formation 8. Other iatrogenic causes of cracked tooth syndrome include excessive hydraulic pressure in luting agents when cementing crowns11or bridge retainers 12. Long-span bridges exert excessive torque on the abutment teeth, leading to crack generation 8.

The higher incidence of cracked tooth syndrome in mandibular second molars may be associated with their proximity to the temporo-mandibular joint 4, based on the principle of the“lever” effect — the mechanical force on an object is increased at closer distances to the fulcrum 13. Eccentric contacts expose these teeth to significant occlusal trauma in this manner 14. Functional forces on teeth that have untreated carious lesions can also lead to crack formation 8.

Cracked tooth syndrome has been reported in pristine (unrestored) teeth 8 or in those with minor restorations, which has led to the suggestion that there may be developmental weaknesses (arising within coalescence of the zones of calcification) within those teeth 13. This contrasts with the findings of Cameron, who claimed that the teeth involvedwere usually quite heavily restored 5. Thermal cycling 15 and damaging horizontal forces or parafunctional habits havealso been implicated in the development of enamel cracks in such unrestored teeth, with subsequent involvement of the underlying tooth 4. There are reports in the recent literature of the generation of such cracks associated withlingual barbells 16.

Cracked tooth syndrome prevention

Most tooth fractures cannot be avoided because they happen when you least expect them. However, you can reduce the risk of breaking teeth by:

- Trying to eliminate clenching habits during waking hours,

- Avoiding chewing hard objects (eg bones, pencils, ice),

- Avoiding chewing hard foods such as pork crackling and hard-grain bread

Awareness of the existence and cause of cracked tooth syndrome is an essential component of its prevention 5. It is very important to preserve the strength of your teeth so they are not as susceptible to fracture. Try to prevent dental decay and have it treated early. Heavily decayed and therefore heavily filled teeth are weaker than teeth that have never been filled. Individuals who have problems with tooth wear or “cracked tooth syndrome” should consider wearing a nightguard while sleeping. This will absorb most of the grinding forces. Relaxation exercises may be beneficial.

Cavities should be prepared as conservatively as possible 17. Rounded internalline angles should be preferred to sharp line angles to avoid stress concentration. Adequate cuspal protection should be incorporated in the design of cast restorations 4. Cast restorations should fit passively to prevent generationof excess hydraulic pressure during placement 18. Pinsshould be placed in sound dentine, at an appropriatedistance from the enamel to avoid unnecessary stress concentration 11. The prophylactic removal of eccentric contacts has been suggested for patients with a history ofcracked tooth syndrome to reduce the risk of crack formation, though there is little clinical evidence to support this practice 19.

Cracked tooth syndrome symptoms

Pain when you chew or when you bite are indicators of cracked tooth syndrome. If you are constantly grinding and clenching your teeth, having your dentist check your teeth for cracks is also a must. The crack will expose the inside of the tooth (the ‘dentine’) that has very small fluid filled tubes that lead to the nerve (‘pulp’). Flexing of the tooth opens the crack and causes movement of the fluid within the tubes. When you let the biting pressure off the crack closes and the fluid pressure simulates the nerve and causes pain.

Symptoms of cracked tooth syndrome include:

- Tooth sensitivity to hot and cold temperatures.

- Pain in the tooth upon biting or chewing. Pain is not constant as that in case of tooth decay or tooth abscess. The tooth may be painful only when eating certain foods or when chewing in a specific way. If the pain is usually experienced upon release of biting pressure, it is a sign that it is a case of cracked tooth syndrome.

- If the crack is severe, there may be signs of increased tooth mobility.

Cracked tooth syndrome diagnosis

Successful diagnosis of cracked tooth syndrome requires awareness of its existence and of the appropriate diagnostic tests 20. The history elicited from the patient can give certain distinct clues. Pain on biting that ceases after the pressure has been withdrawn is a classical sign 8. Incidences usually occur while eating or where objects such as a pencil or a pipe are placed between the teeth 8. The patient may have difficulty in identifying the affected tooth (there are no proprioceptive fibers in the pulp chamber) 21. Vitality testing usually gives a positive response 4 and the tooth is not normally tender to percussion in an axial direction 21. Significantly, symptoms can be elicited when pressure is applied to an individual cusp 9. This is the principle of the so-called “bite tests” where the patient is instructed to bite on various items such as a toothpick, cotton roll, burlew wheel, wooden stick 4 or the commercially available Tooth Slooth 4. Pain increases as the occlusal force increases, and relief occurs once the pressure is withdrawn (though some patients may complain of symptoms after the force on the tooth has been released) 3. The results of these “bite tests” are conclusive in forming a diagnosis of cracked tooth syndrome.

The tooth often has an extensive intracoronal restoration 22. There may be a history of courses of extensive dental treatment, involving repeated occlusal adjustments 5 or replacement of restorations, which fail to eliminate the symptoms. The pain may sometimes occur following certain dental treatments, such as the cementation of an inlay, which may be erroneously diagnosed as interferences or “high spots” on the new restoration 22. Recurrent debonding of cemented intracoronal restorations such as inlays may indicate the presence of underlying cracks 5. Heavily restored teeth may also be tested by application of a sharp probe to the margins of the restoration. Pain evoked in this manner can indicate the presence of a crack in the underlying tooth, which may be revealed upon removal of the restoration 23.

Patients with a previous incidence of cracked tooth syndrome can frequently self-diagnose their condition. Diagnosis should exclude pulpal, periodontal or periapical causes of pain 21. Galvanic pain associated with recent placement of amalgam restorations should also be considered in this differential diagnosis 8. Such pain occurs on closing the teeth together but decreases as full contact is made, unlike cracked tooth syndrome where the pain increases as the teeth close further together, due to increasing occlusal force 8. The medical history should also be considered to exclude incidences of orofacial pain or psychiatric disorders 3.

Visual inspection of the tooth is useful, but cracks are notoften visible without the aid of a microscope, specialized techniques such as transillumination 3 or staining with dyes such as methylene blue 23. Particular attention should be paid to mesial and distal marginal ridges 23. Cracks are sometimes stained by caries or food and are visible to the unaided eye. Not all stained and visible crack lines lead to the development of cracked tooth syndrome. Other clues evident on examination include the presence of facets on the occlusal surfaces of teeth (identifies teeth involved in eccentric contact and at risk from damaging lateral forces) 9, the presence of localized periodontal defects (found where cracks extend subgingivally) 3, or the evocation of symptoms by sweet or thermal stimuli 4. Radiographic examination is usually inconclusive as cracks tend to run in a mesiodistal direction 4.

Cracked tooth syndrome treatment

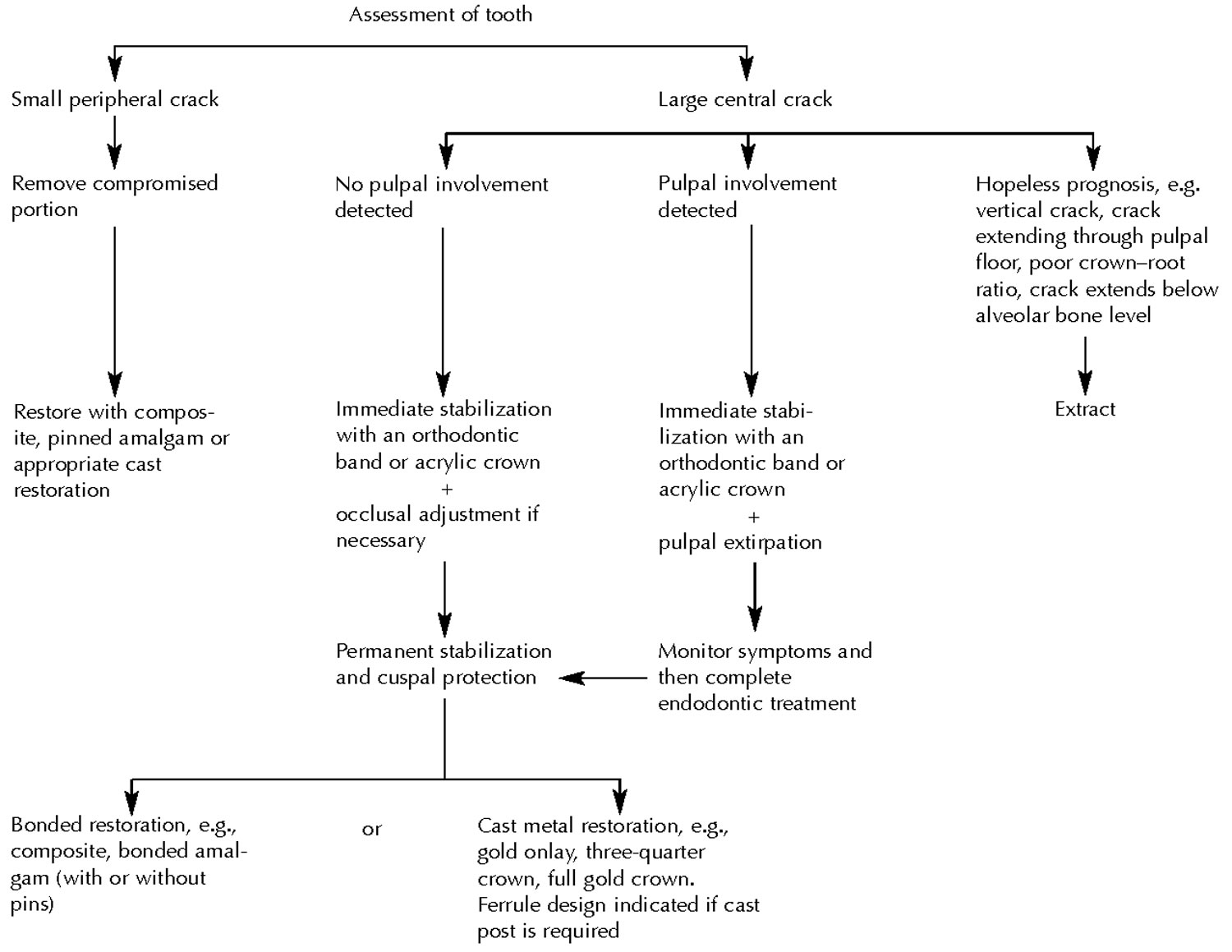

A decision flowchart of cracked tooth syndrome treatment options is presented in Figure 1. Immediate treatment of the tooth depends on the size of the involved portion of the tooth. If the tooth portion is relatively small and avoids the pulp, it may be fractured off and the tooth restored in the normal way 4. If, however, the portion is very large or involves the pulp, the tooth should be stabilized immediately with an orthodontic stainless steelband 4. Stabilization, along with occlusal adjustment 9, can lead to immediate relief of symptoms. Care should betaken to prevent microleakage along the crack line, as this could result in pulpal necrosis 4. A high success rate has been reported when full-coverage acrylic provisional crowns were used to stabilize the compromised tooth 24. The tooth should be examined after 2 to 4 weeks and if symptoms ofirreversible pulpitis are evident, endodontic treatmentshould be performed 4.

Figure 1. Cracked tooth syndrome treatment flowchart

[Source 20 ]

[Source 20 ]

Ultimately the tooth needs to be restored with protection and permanent stabilization in mind 9. This can be achieved with an adhesive intracoronal restoration (e.g., bonded amalgam, adhesive composite restorations) 11 or a cast extracoronal restoration1 (e.g., full-coverage crown,onlay or three-quarter crown with adequate cuspal protection) to bind the remaining tooth components together 4. While there has been a lot of interest in the benefits of such adhesive restorations, there is, as yet, little clinical evidence in the literature to support their use. As for extracoronal restorations, certain modifications of tooth preparation have been suggested for cracked teeth, such as including additional bracing features in the area of the crack, i.e.,extending the preparation in a more apical direction, bevelling the cusps of the fractured segment more than usual to minimize damaging forces, using bases to prevent contactwith the internal surface of the casting, and using boxes andgrooves on the unfractured portion 25. Cracks extendingsubgingivally often require a gingivectomy to expose themargin;3however, an unfavourable crown–root ratio may render the tooth unrestorable.

Where vertical cracks occur or where the crack extendsthrough the pulpal floor or below the level of the alveolarbone, the prognosis is hopeless and the tooth should beextracted 3.

It is worth remembering that it is possible for a crack to progress after placement of an extracoronal metal restoration or crown, when occlusal forces are particularly strong.

If you think you grind your teeth at night, ask your dentist if a nightguard or a splint will be of use to you.

References- Hasan S, Singh K, Salati N. Cracked tooth syndrome: Overview of literature. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. 2015;5(3):164–168. doi:10.4103/2229-516X.165376 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4606573

- Ellis SG, Macfarlane TV, McCord JF. Influence of patient age on the nature of tooth fracture. J Prosthet Dent 1999; 82(2):226-30.

- Türp JC, Gobetti JP. The cracked tooth syndrome: an elusive diagnosis. J Am Dent Assoc 1996; 127(10):1502-7.

- Ehrmann EH, Tyas MT. Cracked tooth syndrome: diagnosis, treatment and correlation between symptoms and post-extraction findings. Aust Dent J 1990; 35(2):105-12.

- Cameron CE. Cracked-tooth syndrome. J Am Dent Assoc 1964; 68(March):405-11.

- Stanley HR. The cracked tooth syndrome. J Am Acad Gold Foil Oper 1968; 11(2):36-47.

- Ritchey B, Mendenhall R, Orban B. Pulpitis resulting from incomplete tooth fracture. Oral Med Oral Surg Oral Pathol 1957; 10(June):665-70. 6. Sutton PRN. Greenstick fractures of the tooth crown. Br Dent J 1962; 112(May 1):362-3.

- Rosen H. Cracked tooth syndrome. J Prosthet Dent 1982; 47(1): 36-43.

- Bales DJ. Pain and the cracked tooth. J Indiana Dent Assoc 1975; 54(5):15-8.

- cracked tooth syndromeBales DJ. Pain and the cracked tooth. J Indiana Dent Assoc 1975; 54(5):15-8.

- Bearn DR, Saunders EM, Saunders WP. The bonded amalgam restoration — a review of the literature and report of its use in the treatment of four cases of cracked-tooth syndrome. Quintessence Int 1994; 25(5):321-6.

- Trushkowsky R. Restoration of a cracked tooth with a bonded amalgam. Quintessence Int 1991; 22(5):397-400.

- Hiatt WH. Incomplete crown-root fracture in pulpal-periodontal disease. J Periodontol 1973; 44(6):369-79.

- Swepston JH, Miller AW. The incompletely fractured tooth. J Prosthet Dent 1986; 55(4):413-6.

- Ellis SG. Incomplete tooth fracture — proposal for a new definition. Br Dent J 2001; 190(8):424-8.

- DiAngelis AJ. The lingual barbell: a new etiology for the crackedtooth syndrome. J Am Dent Assoc 1997; 128(10):1438-9.

- Snyder DE. The cracked-tooth syndrome and fractured posterior cusp. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1976; 41(6):698-704.

- Rosen H. Cracked tooth syndrome. J Prosthet Dent 1982; 47(1) 36-43.

- Agar JR, Weller RN. Occlusal adjustment for initial treatment and prevention of the cracked tooth syndrome. J Prosthet Dent 1988; 60(2):145-7.

- Lynch, C.D., & Mcconnell, R.K. (2002). The cracked tooth syndrome. Journal, 68 8, 470-5.

- Gibbs JW. Cuspal fracture odontalgia. Dent Dig 1954; 60(April): 158-60.

- Goose DH. Cracked tooth syndrome. Br Dent J 1981; 150(8):224-5.

- Abou-Rass M. Crack lines: the precursors of tooth fractures — their diagnosis and treatment. Quintessence Int 1983; 14(4):437-47.

- Guthrie RG, DiFiore PM. Treating the cracked tooth with a full crown. J Am Dent Assoc 1991; 122(10):71-3.

- Casciari BJ. Altered preparation design for cracked teeth. J Am Dent Assoc 1999; 130(4):571-2.