What is craniosynostosis

Craniosynostosis is a birth defect of the skull characterized by the premature closure of one or more of the cranial sutures or fibrous joints between the bones of the skull (joints between the bone plates) before brain growth is complete 1. Closure of a single suture is most common. Normally the skull expands uniformly to accommodate the growth of the brain and most cranial sutures fuse when a person is 20-30 years of age, with the exception being the metopic suture fusing around 6 months to 2 years; premature closure of a single suture restricts the growth in that part of the skull and promotes growth in other parts of the skull where sutures remain open. This results in a misshapen skull but does not prevent the brain from expanding to a normal volume. However, when many sutures close prematurely, the skull cannot expand to accommodate the growing brain, which leads to increased pressure within the skull and impaired development of the brain. Theoretically, a person can suffer consequences of an early skull suture fusion no matter what age it fuses. However, doctors usually see the most severe consequences when the fusion happens early in life, often before birth.

Craniosynostosis usually involves fusion of a single cranial suture, but can involve more than one of the sutures in your baby’s skull (complex craniosynostosis). In rare cases, craniosynostosis is caused by certain genetic syndromes (syndromic craniosynostosis).

Types of craniosynostosis are:

- Sagittal synostosis (scaphocephaly) is the most common type. It affects the main suture on the very top of the head. The early closing forces the head to grow long and narrow, instead of wide. Babies with this type tend to have a broad forehead. It is more common in boys than girls.

- Frontal plagiocephaly is the next most common type. It affects the suture that runs from ear to ear on the top of the head. It is more common in girls.

- Metopic synostosis is a rare form that affects the suture close to the forehead. The child’s head shape may be described as trigonocephaly. It may range from mild to severe.

Craniosynostosis can be gene-linked or caused by metabolic diseases (such as rickets or vitamin D deficiency) or an overactive thyroid. Some cases are associated with other disorders such as microcephaly (abnormally small head) and hydrocephalus (excessive accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain). The first sign of craniosynostosis is an abnormally shaped skull. Other features can include signs of increased intracranial pressure, developmental delays, or impaired cognitive development, which are caused by constriction of the growing brain. Seizures and blindness may also occur.

Primary craniosynostosis affects individuals of all races and ethnicities and is usually present at birth. Most forms of primary craniosynostosis affect men and women in equal numbers (although males outnumber females 2:1 for sagittal synostosis). Primary craniosynostosis affects approximately 0.6 in 100,000 people in the general population. Overall, craniosynostosis affects approximately 1 in 2,000-2,500 people in the general population. Approximately 80-90 percent of individuals with primary craniosynostosis have isolated defects. The remaining cases of primary craniosynostosis occur as part of a larger syndrome. More than 150 different syndromes have been identified that are potentially associated with craniosynostosis.

In most cases of primary craniosynostosis, affected children usually have normal intelligence and do not have other abnormalities besides the skull malformation. However, when multiple sutures are affected, the skull may be unable to expand enough to accommodate the growing brain. If left untreated, this can cause increased pressure within the skull (intracranial pressure) and can potentially result in cognitive impairment or developmental delays. Increased pressure within the skull can also cause vomiting, headaches, and decreased appetite. In some rare cases, additional symptoms can develop including seizures, misalignment of the spine, or eye abnormalities.

Treatment for craniosynostosis generally consists of surgery to improve the symmetry and appearance of the head and to relieve pressure on the brain and the cranial nerves. For some children with less severe problems, cranial molds can reshape the skull to accommodate brain growth and improve the appearance of the head.

Although neurological damage can occur in severe cases, most children have normal cognitive development and achieve good cosmetic results after surgery. Early diagnosis and treatment are key.

Does the exact time a suture prematurely fuses affect my child?

Yes. Because of the rapid brain growth in the first two years of life, the brain really relies on the sutures to grow the skull during this period. So the earlier in pregnancy the suture fuses, the greater the restriction. Clinically, this is seen as a more severe change in the shape of the head with earlier fusions. For example, a patient with a sagittal suture fusion that occurs in the second trimester of pregnancy will have a much more “scaphocephalic” skull than a patient that has a fusion occur at 6 months after birth. The earlier fusion will have a more significant effect on head shape compared to a later fusion that may produce a relatively normal appearing skull. There is a correlation with the degree of deformity and the restriction in volume. Consequently, the more severe restriction leads to a more severe increase in pressure that the brain experiences. So it follows that the earlier the fusion, the more likely a patient is to experience abnormally increased intracranial pressure earlier in life. There is not a lot of longitudinal data demonstrating this primarily because most kids showing increased intracranial pressure are operated early in life. We do, however, see this trend clinically.

What are the concerns about a fused suture?

There are a couple of concerns associated with a fused skull suture. First and foremost, the skull is not growing adequately to afford sufficient volume and configuration of the endocranial cavity for the developing brain. Inadequate endocranial volume leads to an increase in pressure within the brain cavity. As the disproportion between endocranial volume and brain volume veers further away from normal, the fluid spaces around and within the brain become compressed, and eventually the brain tissue itself becomes compressed.

Since the brain depends on a large percentage of heart’s output (roughly 30%) to function properly, there is an important hydrostatic gradient between systemic blood pressure and intracranial pressure that is necessary to keep the brain functioning well. There is not an exact answer to the question of “what is normal intracranial pressure” because we have never been able to establish experimentally in what range the best functioning brains in the world exist compared to lower functioning brains. Experimental data suggests that a good estimation of “normal” pressure” is less than 15 mm Hg on average in patients with normal blood pressure. Brains that exist in a range below 15 mmHg seem to be happy and function at their best. We all know from everyday life that a certain activity, like lifting a heavy weight, may be associated with a full feeling in the head. This feeling is caused by obstructed blood flow from the brain back to the heart. The blood backs up in the brain temporarily and leads to transient high pressure. So periods of high pressure are clearly normal for much of what we do as humans. We don’t get too excited by these occasional activity related “high pressure spikes”. However, when a patient experiences a lot of these spikes or their pressure is consistently above 20 mm Hg or so, we start to become concerned.

Another concern of some parents, and less to others, is the shape of the head and its impact on how the child appears when compared to other children. Obviously, the degree of deformity and the value a family attributes to appearance have a great impact here. There are clearly cases of children with very late onset craniosynostosis that have very little change in their external appearance; patients with early, in-utero fusion often have a much more noticeable difference in their external appearance compared to other children. The value of appearance is a very personal consideration. It is important for each patient and family to feel free to express his or her own opinions on this issue. While never the sole concern in the context of craniosynostosis, a family’s opinion on this issue is always valid and important to understand when making decisions on whether or not to treat the disorder, especially surgically.

Craniosynostosis prognosis

How well a child does depends on:

- How many sutures are involved

- The child’s overall health

Children with this condition who have surgery do well in most cases, especially when the condition is not associated with a genetic syndrome.

Craniosynostosis possible complications

Craniosynostosis results in head deformity that can be severe and permanent if it is not corrected. Complications may include:

- Increased intracranial pressure

- Seizures

- Developmental delay

- Permanent head and facial deformity

- Poor self-esteem and social isolation

The risk of intracranial pressure from simple craniosynostosis is small, as long as the suture and head shape are fixed surgically. But babies with complex craniosynostosis (syndromic craniosynostosis), particularly those with an underlying syndrome, may develop increased pressure inside the skull if their skulls don’t expand enough to make room for their growing brains. If untreated, increased intracranial pressure can cause:

- Developmental delays

- Cognitive impairment

- No energy or interest (lethargy)

- Blindness

- Eye movement disorders

- Seizures

- Death, in rare instances

Normal newborn skull anatomy and physiology

It is important to have an understanding of skull anatomy and growth in order to understand craniosynostosis. An infant’s skull has 7 bone plates that relate to each other through specialized joints called “cranial sutures”. Sutures are made of tough, elastic fibrous tissue and separate the bones from one another. Sutures meet up (intersect) at two spots on the skull called fontanelles, which are better known as an infant’s “soft spots”. Although there are several major and minor sutures, the sutures that potentially have the most clinical significance are the singular metopic and sagittal sutures, as well as the paired (right and left) coronal and lambdoid sutures (see Figure 1). The seven bones of an infant’s skull normally do not fuse together until around age two or later. The sutures normally remain flexible until this point. In infants with primary craniosynostosis, the sutures abnormally stiffen or harden causing one or more of the bones of the skull to prematurely fuse together. This in turn, may lead to asymmetric skull growth.

Cranial sutures are very unique and specialized joints (syndesmosis joints). Their primary purpose is to grow bone in response to the rapidly developing brain within the protective skull compartment (cranial cavity or calvarium). The skull not only needs to be firm to protect the brain from accidental blows, but should also be expansile to accommodate its rapid growth. The brain doubles in volume in the first year of life and almost triples in volume by the age of three. The sutures of the skull allow for this important but almost contradictory balance of protection and growth.

Each cranial suture is designed to generate growth in the skull in a very specific area and configuration, ultimately reflecting the size and shape of the underlying brain structure. The overall bone development from cranial sutures occurs in a direction perpendicular to the long axis of the suture. Understanding these two facts, it makes sense that a fusion of each suture independently would cause a unique head shape.

The greatest increase in brain volume (brain growth) occurs from 0 to 14 months of age. The size of a child’s brain typically reaches 80% of adult size by the age of 2. The growth in head circumference after that age is more related to growth in the thickness of the skull and scalp but not actual brain growth. “Hat size” increases but not necessarily “brain size”.

The various cranial sutures close at different ages. The metopic suture closes earliest, around 6 months to 2 years. The rest of the sutures stay open into the 20’s and 30’s. The brain and fluid cavities of the brain do continue to grow in volume as you go into early adulthood, albeit not nearly as rapidly as the first couple years of life. Since the skull is much firmer (calcified or “rock-like”) and thicker, the skull needs the sutures to grow bone for any increase in volume.

Interestingly, there is a lot of variability here. Doctors have operated on adults in their 30’s for reasons unrelated to their skull sutures and have coincidentally found open metopic sutures. They have also seen young adults with closed coronal, lambdoid, and sagittal sutures, but with normal head shapes and often, no indication or symptoms of high pressure.

Scientists have learned that a cranial suture’s purpose is to grow bone to accommodate a growing brain, and that most brain growth occurs in the first two years of life. The brain reaches 85% of adult size by age 3 years (see Figure 2. Brain size vs. age diagram).

So it makes sense that the sutures are vitally important in the first two years of life. The earlier the fusion, the more severe the restriction in growth and, consequently, volume provided to the brain.

Figure 1. Normal skull of a newborn

Figure 2. Brain size versus age diagram

Craniosynostosis classification

Craniosynostosis are classified as primary or secondary. Primary craniosynostosis results from genetic and environmental influences, being classified as simple and complex. Complex craniosynostosis are divided even further into nonsyndromic and syndromic 2.

- Primary craniosynostosis

- Simple (involving a single suture): Sagittal, Coronal, Metopic, and Lambdoid

- Complex (fusion of two or more sutures)

- Nonsyndromic: Bicoronal

- Syndromic: Crouzon, Apert, Pfeiffer, and Saethre-Chotzen

- Secondary craniosynostosis

- Metabolic disorders: Hyperthyroidism, Inborn Errors of Metabolism

- Various malformations: Microcephaly, Encephalocele

- After ventricular shunt with excessive drainage of CSF (cerebrospinal fluid)

- Fetal exposure to certain substances: Valproic acid, Phenytoin

- Mucopolysaccharidosis

Craniosynostosis types

Craniosynostosis may be subdivided based upon the exact cranial sutures and skull bones involved. Most cases of primary craniosynostosis involve only one suture. Each subdivision results in a different characteristic pattern of skull development. The subdivisions of craniosynostosis include sagittal synostosis, coronal synostosis, metopic synostosis, and lambdoid synostosis. Synostosis is a medical term for the fusion of bones that are normally separate.

In rare cases, individuals with primary craniosynostosis have premature fusion of multiple sutures also known as complex craniosynostosis. A specific form of complex craniosynostosis involving multiple sutures is known as Kleeblattschadel (which is German for “cloverleaf” ) deformity. Fusion of multiple sutures causes the skull to appear flattened and divided into three lobes, thus resembling a cloverleaf. Most cases of complex craniosynostosis are linked to genetic syndromes and are called syndromic craniosynostosis. Kleeblattschadel deformity usually occurs as part of a syndrome.

Other reasons for a misshapen head

A misshapen head doesn’t always indicate craniosynostosis. For example, if the back of your baby’s head appears flattened (positional plagiocephaly or brachycephaly), it could be the result of your baby spending too much time on one side of his or her head. This can be treated with regular position changes, or if significant, with helmet therapy (cranial orthosis) to help reshape the head to a more normal appearance.

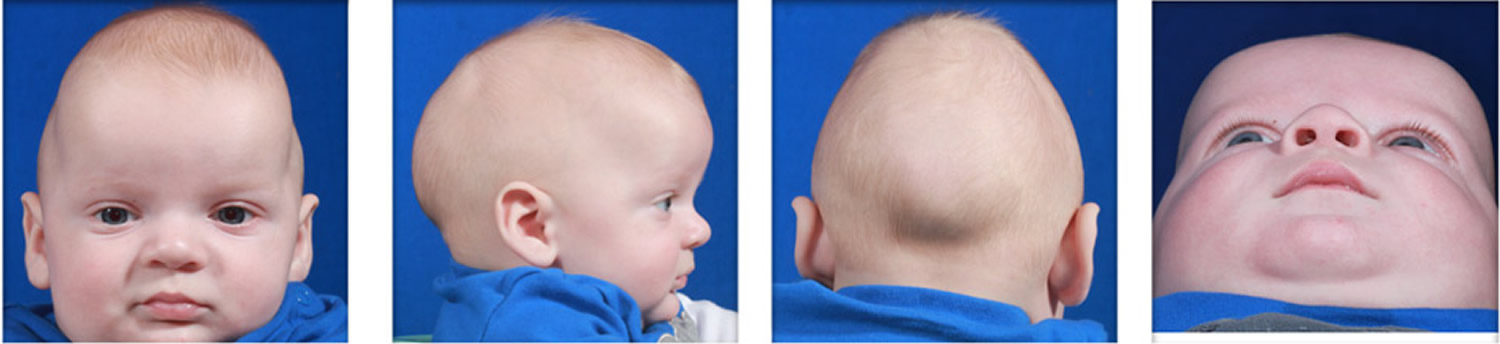

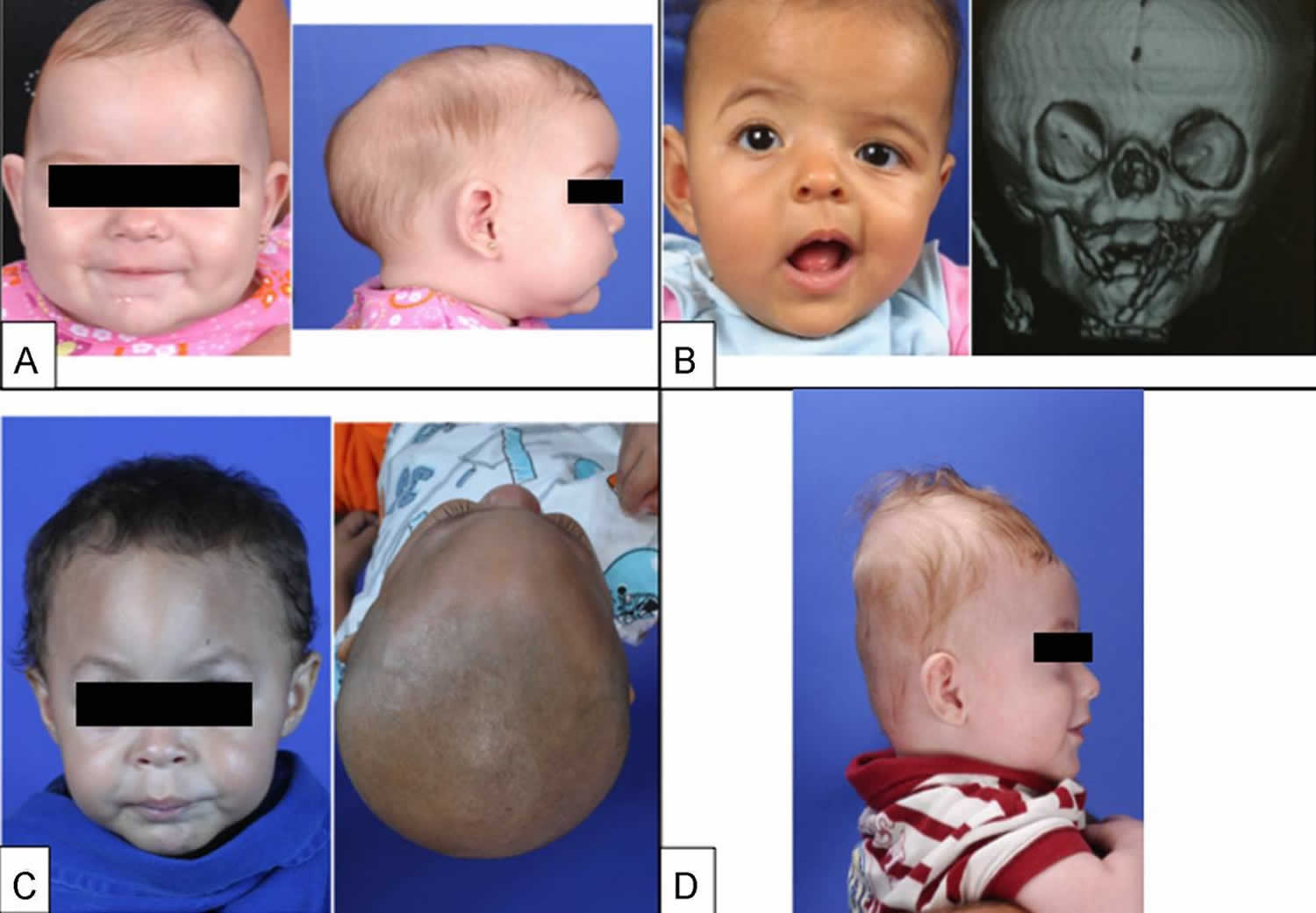

Figure 3. Types of craniosynostosis skull deformity (the following diagrams and clinical pictures demonstrate the unique forms that occur with each suture fusion)

Footnotes: (A, Left) Frontal photograph of patient with premature fusion of sagittal suture showing the characteristic temporal pinching. (Right) Lateral photograph reveling increase in the anterior-posterior diameter of the skull (long narrow skull), the frontal bossing and occipital bulging (occipital bullet), which are the main clinical characteristics of sagittal craniosynostosis. (B, Left) Frontal photograph of patient with premature fusion of the right coronal suture showing the retrusion of the ipsilateral frontal bone fusion and compensatory contralateral bulging, asymmetry of the eyebrows, orbits, ears, nose, jaw, as well as convergent strabismus of the left eye. (Right) 3D CT reconstruction showing the premature fusion of the right coronal suture and the elevation of the ipsilateral sphenoid wing leading to an elongate orbit, recognized as the “harlequin orbit”. (C, Left) Frontal photograph of patient with premature fusion of metopic suture showing the triangular aspect of the forehead with retruded crests of the orbits bilaterally and hypoteleorbitism (approximation of orbits). (Right) Basal view revealing the triangular appearance of the skull. (D) Lateral photograph of patient with premature fusion of lambdoid suture showing the turricephalic aspect of the skull.

[Source 3 ]Sagittal craniosynostosis

The most common form of craniosynostosis is sagittal synostosis (hardening of the sagittal suture) and accounts for 40-60% of cases, being more prevalent among males (75-85%) 3. The sagittal suture is the joint that runs from the front to the back of the skull and that separates the two bones that form the sides of the skull (parietal bones). Premature closure of this suture results in an abnormally long, narrow head (scaphocephaly) similar to a boat due to the restricted sideways growth (width) of the skull (Figures 3A and 4) 4. Upon physical examination, a ridge can be palpated on the sagittal suture. It should be noted that the anterior fontanelle may not be closed. Compensatory frontal bossing and occipital protrusion may occur in varying degrees.

Surgical treatment is indicated between 3 and 12 months of age, and procedures may vary from a simple endoscopic resection of the sagittal suture to total reconstruction of the skull, depending on the severity of the clinical presentation. In our service, we recommend surgery between 6 and 9 months of age and use the craniectomy in a “π” fashion (named Hung Spun procedure) 5, associated with several osteotomies (bone cuts) parallel rectangles of approximately two centimeters long in the parietal bone, between the coronal and lambdoid sutures, which permit greater lateral space for further accommodation of the brain. Barrel stave osteotomies (lateral bone cuts) still allow for reduction of the anterior posterior diameter and better remodeling of the skull, with excellent esthetic results 6.

Figure 4. Sagittal craniosynostosis

Coronal craniosynostosis

Coronal synostosis refers to the premature closure of one of the coronal sutures, which are the joints that separate the two frontal bones from the two parietal bones. The coronal sutures extend across the skull, almost from one ear to the other. The two coronal sutures meet at the “soft spot” (anterior fontanelle) located toward the front and of the skull. Coronal synostosis is the second most common form, accounting for up to 25% of craniosynostosis cases 3. The closure of a coronal suture is called anterior plagiocephaly 7, while the closure of two sutures is termed brachycephaly (commonly found in syndromic craniosynostosis) 8. Coronal synostosis predominantly affects females (60%), with similar incidence on both sides.

Premature fusion of one of the coronal sutures (unicoronal) that run from each ear to the top of the skull may cause your baby’s forehead to flatten on the affected side and bulge on the unaffected side. It also leads to turning of the nose and elevation of the eye socket on the affected side. The skull may appear twisted or lopsided and the forehead and orbit of the eye may appear flattened on one side whereas the opposite side of the forehead may appear to bulge as part of the brain’s unrestricted growth on this side. This specific skull shape is sometimes referred to as frontal plagiocephaly. Strabismus is a common finding (50-60% of cases) and is the result of morphological changes in the orbital roof and trochlea, altering the function of the superior oblique muscle 9. Elevation of the ipsilateral sphenoid wing can be seen in simple skull radiography and is recognized as the “harlequin orbit” (Figure 3B) 10. Premature fusion of the coronal suture also causes a deviation of the skull base, changing the position of the orbits, asymmetry of the eyebrows, asymmetry of the ear position, deviation of the mandible, and change of occlusion, with an important esthetic effect 7.

When both of the coronal sutures fuse prematurely (bicoronal), it causes the skull to appear abnormally short and disproportionally wide (brachycephaly), it gives your baby’s head a short and wide appearance, most commonly with the forehead tilted forward.

Surgical treatment is indicated for correction of the morphological skull deformity and its repercussions on the face, but also because of strabismus and risks of developing intracranial hypertension. Experts recommend the procedure between 6 and 9 months of age, when there is already sufficient bone maturity for remodeling. Basically, a front-orbital advancement associated with frontal remodeling is performed and releasing both coronal sutures 7. Further procedures might be necessary as fat injection in the craniofacial skeleton to decrease facial asymmetries and correction of eyelid ptosis. At the end of facial growth orthognatic surgery and rhinoplasty with septoplasty may be performed by a plastic surgeon with a craniofacial training.

Figure 5. Unicoronal synostosis (anterior plagiocephaly or unilateral coronal synostosis)

Footnote: The right eyebrow is raised with retrusive forehead and the nasal root is deviated to the right in this instance of unicoronal synostosis.

- Asymmetrical forehead and brow

- Lack of forward growth on the affected side, resulting in flatness and retrusion

- Harlequin deformity: the eye socket on the affected side appears taller than the other eye, resulting in an eye that appears more widely open, and the bridge of the nose is bent toward the affected side of the face

Figure 6. Bicoronal synostosis

Footnote: A tall forehead and wide head shape is characteristic of bicoronal synostosis.

- Disproportionately wide and flat head

- Flat back of the head and often extreme forehead incline (height)

Metopic craniosynostosis

Metopic synostosis refers to the premature fusion of the metopic suture, which is the joint that separates the two frontal bones of the skull. It runs from the top of the forehead to the anterior fontanelle (frontal soft spot). Early fusion of the metopic suture restricts the transversal growth of frontal bones, and in more severe cases can restrict the expansion of the anterior fossa, which leads to hypoteleorbitism, and consequently to trigonocephaly (Figure 3C). This condition causes a keel-shaped forehead and eyes that are set closer together than normal (hypotelorism). When viewed from above the skull may appear to be shaped triangularly, a condition referred to as trigonocephaly. A ridge may be apparent running down the middle of the forehead, which may appear narrow. The soft spot found toward the back of the skull (anterior fontanelle) is usually absent or prematurely closed. The presence of a metopic ridge (a palpable/ visible prominence over the midline of the forehead) is relatively common and not all individuals with this ridge have trigonocephaly.

Metopic synostosis corresponds to 10% of all craniosynostosis and predominates in males (75-85% of cases). Metopic craniosynostosis is the single suture synostosis most frequently associated with more cognitive disorders, primarily due to the growth restriction of the frontal lobes 11.

The increase in the anterior fossa volume is the main objective in the treatment of patients with trigonocephaly, as well as frontal remodeling and fronto-orbital advancement. The best time for treatment is between 6 and 9 months of age 3.

Figure 7. Metopic craniosynostosis

Footnote: Constriction in the temporal regions and triangular-shaped forehead are characteristic of metopic synostosis.

- Triangular-shaped forehead when viewed from above

- Eyes may appear closer together

- Forehead will appear to jut out in the middle or appear more prominent when looking directly at the face

Lambdoid craniosynostosis

Lambdoid synostosis, also known as posterior plagiocephaly, is the premature fusion of the lambdoid suture, which is the joint that separates the bone that forms the lower back of the skull (occipital bone) from the parietal bones. One side of the rear of the head may appear flatter than the other when viewed from above. The ear on the affected side may be pulled backward and stick out farther than the other ear. A small bump may also be present behind the ear on the affected side. Whereas true lambdoid synostosis is extremely rare (1/200,000), this should not be confused with the nearly ubiquitous lambdoid positional plagiocephaly. Fortunately, there are physical features that help to differentiate these two conditions and children with positional plagiocephaly usually have compensatory overgrowth at the forehead on the same side.

Lambdoid synostosis is the rarest form of simple craniosynostosis, with an incidence of about 0.3 per 10,000 live births, corresponding to approximately 1.0-5.5% of all craniosynostosis 3. When evaluated in a population of children with occipital flattening (also called posterior plagiocephaly), it is responsible for only 0.9-4.0% of the cases 12.

Fusion of a lambdoid suture leads to an occipital deformity (posterior plagiocephaly) with a trapezoidal shape, while the fusion of both lambdoid sutures leads to brachycephaly (Figure 3D). In addition to posterior deformity (flattening, poor positioning of ears, parietal compensatory bossing) caused by premature fusion of the lambdoid suture, significant morphological changes may occur concomitantly in the posterior fossa. This craniosynostosis is associated with herniated cerebellar tonsils (also known as Chiari malformation type I) and fusion of the jugular foramen, resulting in a high risk of venous hypertension. Thus, this is the form of simple craniosynostosis with the greatest risk of intracranial hypertension 13.

Surgical treatment is based on volume expansion of the posterior portion of the skull (parietal and occipital region) and releasing the lambdoid sutures. However, this region has large venous drainage, with innumerable scalp veins that cross the bone toward the dural sinuses, greatly increasing the surgical risk of a craniotomy and bone remodeling. In our service, we choose a posterior distraction technique, in which the cranial volume is gradually increased, significantly reducing the risk of bleeding and need for blood transfusions 14.

Figure 8. Lambdoid craniosynostosis (posterior plagiocephaly)

Footnote: (Left) Asymmetric flattening of the back lower-right side of the head, characteristic of unilateral lambdoid synostosis. (Right) Growth restriction on the back-right side of the head with compensatory growth of the brain and skull to the left.

- Trapezoid shape

- Early closure causes a flattening on the back of the head on the same side where the suture has fused

- On the affected side, the ear is often posteriorly displaced, moved toward the back of the head or set lower than the non-affected ear, which is a distinguishing feature

- Bossing, or protrusion, at the back of the head on the non-affected side

- Atypical bulge in the mastoid region generally visible

Craniosynostosis symptoms

The signs of craniosynostosis are usually noticeable at birth, but they’ll become more apparent during the first few months of your baby’s life.

Symptoms depend on the type of craniosynostosis. They may include:

- No “soft spot” (fontanelle) on the newborn’s skull

- Development of a raised, hard ridge along affected sutures

- Unusual head shape or a misshapen skull, with the shape depending on which of the sutures are affected

- An abnormal feeling or disappearing fontanel on your baby’s skull

- Slow or no increase in the head size over time as the baby grows

Often the most obvious sign of craniosynostosis is a unique head shape and orbital asymmetry, although craniosynostosis is not the only cause of a unique head shape. Our team has strong experience in evaluating unique head shapes, determining the cause of each one, and deciphering out other causes from craniosynostosis.

In addition to a unique head shape, the signs and symptoms of elevated intracranial pressure may or may not be present. The most consistent symptom of elevated pressure is the presence of chronic, recurrent headaches. Because there are many different causes of headaches, it is important to distinguish between the patterns of headaches caused by increased intracranial pressure and those that are caused by other reasons. Again, multidisciplinary experience plays an important role in this.

Prolonged elevated pressure and very high pressure cause irreversible damage to the optic nerves (nerves that are key to vision). Sometimes this damage can be found by examination of the retina by a pediatric ophthalmologist (a medical doctor of the eyes). The physical exam finding is called papilledema. Once papilledema is seen on exam, it is an indication that the nerve has suffered a permanent injury that results in worsening vision for the patient.

There is some data to suggest that long-standing or early-onset pressure elevation on the brain can lead to a brain that functions at a lower level than it would have if it never experienced elevated pressure. Longitudinal studies regarding IQ and brain function in children are very difficult to carry out, and comparing these children to unaffected cohorts is riddled with issues that can challenge the validation of these studies. Clinically, children who are experiencing very high pressure from other conditions, like hydrocephalus, do not function very well. Pressure can get so high in some of these cases that it can become life threatening. While most children with craniosynostosis do not experience pressure as high as hydrocephalus, we do see similar pressure effects on some patients with the higher end of the pressure spectrum. The effects of long standing, low-grade pressure are much less clear, for sure.

Lastly, there are a number of radiographic signs that the team looks for on imaging studies. No one sign indicates high pressure, but the presence of several of them together usually supports a presumptive diagnosis of elevated intracranial pressure. A “copper-beaten” pattern to the inner cranial surface, loss of extra-axial fluid spaces, narrowing of the ventricles, effacement of the sulci, and blunting of cerebral gyri all indicate some degree of cephalo-cranial disproportion or, simply, a mismatch between the size of the brain and the volume provided to it by the skull.

Related disorders

Symptoms of the following disorders can be similar to those of primary craniosynostosis. Comparisons may be useful for a differential diagnosis.

Secondary craniosynostosis refers to the development of an abnormal skull shape due to the premature closure of the cranial sutures that occurs because of a primary failure of brain growth. Proper brain growth pushes the bones of the skull apart, a normal process to allow the skull to accommodate the growing brain. Failure of proper brain growth allows the bones to fuse together prematurely. A variety of different underlying causes can result in the failure of brain growth and subsequent craniosynostosis. These causes include metabolic disorders, certain blood (hematological) disorders, malformation disorders, and the exposure of the fetus to certain drugs including valproic acid or phenytoin. Secondary craniosynostosis is usually associated with additional symptoms including facial abnormalities, developmental delays and microcephaly, a condition in which the head circumference is smaller than would be expected for an infant’s age and sex.

Deformational (positional) plagiocephaly, sometimes known as positional plagiocephaly, is a condition in which the skull becomes misshapen due to repeated or constant pressure on a specific area of the skull. Deformational (positional) plagiocephaly is not associated with premature fusion of cranial sutures. It is caused by external forces acting on an infant’s skull. It can develop before birth or after birth. The incidence of deformational (positional) plagiocephaly has increased since the American Academy of Pediatrics recommended that newborns sleep on their backs to prevent sudden infant death syndrome. This repetitive sleeping pattern results in the flattening of the back of the infant’s head or often preceded by the presence of torticollis at birth. Deformational plagiocephaly is not associated with any other abnormalities and does not affect a child’s development.

Craniosynostosis causes

The exact cause of primary (isolated) craniosynostosis is unknown. Genes may play a role, but there is usually no family history of the condition. More often, it may be caused by external pressure on a baby’s head before birth.

- Nonsyndromic craniosynostosis is the most common type of craniosynostosis, and its cause is unknown, although it’s thought to be a combination of genes and environmental factors.

- Syndromic craniosynostosis is caused by certain genetic syndromes, such as Apert syndrome, Pfeiffer syndrome or Crouzon syndrome, which can affect your baby’s skull development.

Primary isolated craniosynostosis refers to cases that are not associated with a larger syndrome. Most cases occur randomly for no apparent reason (sporadically) although an infant’s position in utero, large size and presence of twins have all been implicated as etiological factors. A variety of different genetic and environmental factors are suspected to play a role in the development of primary isolated craniosynostosis.

In extremely rare cases, primary isolated craniosynostosis is genetic and in such cases is usually inherited as an autosomal dominant trait. Most cases of primary craniosynostosis that occur as part of a syndrome are also inherited as autosomal dominant traits. Genetic diseases are determined by the combination of genes for a particular trait that are on the chromosomes received from the father and the mother. Dominant genetic disorders occur when only a single copy of an abnormal gene is necessary for the appearance of the disease. The abnormal gene can be inherited from either parent, or can be the result of a new mutation (gene change) in the affected individual. The risk of passing the abnormal gene from affected parent to offspring is 50 percent for each pregnancy regardless of the sex of the resulting child.

The most widely accepted theory for the development of primary craniosynostosis is a primary defect in the ossification (hardening) of the cranial bones. The underlying cause of this defect is unknown in primary isolated craniosynostosis. In the syndromic forms, the defect is due to a mutation in a specific gene. Syndromic forms of primary craniosynostosis include Apert syndrome, Crouzon syndrome, Pfeiffer syndrome, Jackson-Weiss syndrome and Saethre-Chotzen syndrome.

However, most children with craniosynostosis are otherwise healthy and have normal intelligence.

Genetic aspects

Multiple hypotheses have been proposed to explain the pathogenesis of craniosynostosis. Both environmental (especially intrauterine fetal head constraint) and genetics factors (single gene mutations, chromosome abnormalities and polygenic background) predispose to craniosynostosis.9 – 11 Mutations in 7 genes (namely, FGFR1, FGFR2, FGFR3, TWIST1, EFNB1, MSX2 and RAB23) are unequivocally associated with Mendelian forms of syndromic craniosynostosis 15. In contrast, the genetic etiology of nonsyndromic craniosynostosis remained poorly understood until very recently 15. In the last years, epidemiologic and phenotypic studies clearly demonstrate that nonsyndromic craniosynostosis is a complex and heterogeneous condition supported by a strong genetic component accompanied by environmental factors that contribute to the pathogenesis network of this birth defect 15. In fact, rare mutations in FGFRs, TWIST1, LRIT3, ALX4, IGFR1, EFNA4, RUNX2, and FREM1 have been reported in a minor fraction of patients with nonsyndromic craniosynostosis 15. The minimum molecular genetic tests recommended for each clinical presentation (syndromic and nonsyndromic craniosynostosis) have been previously published review10 and are out of the scope of this report. Further research of a large population with phenotypically homogeneous subsets of patients is required to understand the complex genetic, maternal, environmental, and stochastic factors contributing to nonsyndromic craniosynostosis 15.

Craniosynostosis diagnosis

Craniosynostosis requires evaluation by specialists, such as a pediatric neurosurgeon or plastic surgeon.

Diagnosis of craniosynostosis may include:

- Physical exam. Your doctor will feel your baby’s head for abnormalities such as suture ridges, and look for facial deformities.

- Imaging studies. A computerized tomography (CT) scan of your baby’s skull can show whether any sutures have fused. Fused sutures are identifiable by their absence, because they’re invisible once fused, or by the ridging of the suture line. A laser scan and photographs also may be used to make precise measurements of the skull shape.

- Genetic testing. If your doctor suspects an underlying genetic syndrome, genetic testing may help identify the syndrome.

A diagnosis of primary craniosynostosis is made based upon identification of characteristic symptoms, a detailed patient history, and a thorough clinical evaluation that includes careful assessment of the shape of the skull. A variety of specialized tests include specialized imaging techniques. Such imaging techniques may include computerized tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), although a head CT is best for evaluating suture / bone involvement. Although there has been recent debate about the need for CT’s prior to surgery (and accompanying radiation), there are a number of literature reports documenting their value in ruling out other suture involvement as well as brain abnormalities. During CT scanning, a computer and x-rays are used to create a film showing cross-sectional images of certain tissue structures. Routine skull x-rays have been discontinued as a routine diagnostic tool in the setting of craniosynostosis due to the lack of sensitivity and frequent inaccuracy.

In some cases, a diagnosis of primary craniosynostosis may be made before birth (prenatally) by ultrasound examination. During an ultrasound, reflected sound waves create an image of the developing fetus. An increasing number of children are also being diagnosed via prenatal MRI.

Craniosynostosis treatment

The treatment of primary craniosynostosis is directed toward the specific symptoms that are apparent in each individual. In general, it is an issue of appearance versus intracranial pressure. Mild cases of craniosynostosis may not need treatment. Your doctor may recommend a specially molded helmet to help reshape your baby’s head if the cranial sutures are open and the head shape is abnormal. In this situation, the molded helmet can assist your baby’s brain growth and correct the shape of the skull.

Surgery is the main form of therapy for affected children, but not all children will require surgery. Surgery is performed to create and ensure that there is enough room within the skull for the developing brain to grow; to relieve intracranial pressure (if present); and to improve the appearance of an affected child’s head. The various surgical approaches (endoscopic, Pi procedures, total calvarial reconfiguration, springs, distraction, etc) each have their unique advantages / disadvantages and are best discussed in detail with the treating physician at the time of evaluation.

Genetic counseling may be of benefit for affected individuals and their families. Other treatment is symptomatic and supportive.

Craniosynostosis surgery

Currently, the only effective treatment for craniosynostosis is surgery. The type and timing of surgery depends on the type of craniosynostosis and whether there’s an underlying genetic syndrome.

The purpose of surgery is to correct the abnormal head shape, reduce or prevent pressure on the brain, create room for the brain to grow normally and improve your baby’s appearance. This involves a process of planning and surgery.

There are three goals of craniosynostosis surgery:

- Expand the intracranial volume sufficiently for the brain to avoid high pressure, including the immediate need for more volume and anticipating the future need for brain growth

- Reconstruct the skull into a normal form and appearance

- Provide an intact skull that is protective of the brain for unrestrictive activity

Surgical planning

Imaging studies can help surgeons develop a surgical procedure plan. Virtual surgical planning for treatment of craniosynostosis uses high-definition 3-D CT scans of your baby’s skull to construct a computer-simulated, individualized surgical plan. Based on that virtual surgical plan, customized templates are constructed to guide the procedure.

Craniosynostosis surgery

A team that includes a specialist in surgery of the head and face (craniofacial surgeon) and a specialist in brain surgery (neurosurgeon) generally performs the procedure. Surgery can be done by endoscopic or open surgery. Both types of procedures generally produce very good cosmetic results with low risk of complications.

- Endoscopic surgery. This minimally invasive surgery may be considered for babies up to age 6 months who have single-suture craniosynostosis. Using a lighted tube and camera (endoscope) inserted through small scalp incisions, the surgeon opens the affected suture to enable your baby’s brain to grow normally. Compared with an open procedure, endoscopic surgery has a smaller incision, typically involves only a one-night hospital stay and usually does not require a blood transfusion.

- Open surgery. Generally, for babies older than 6 months, open surgery is done. The surgeon makes an incision in the scalp and cranial bones, then reshapes the affected portion of the skull. The skull position is held in place with plates and screws that are absorbable. Open surgery typically involves a three- or four-day hospital stay, and blood transfusion is usually necessary. It’s generally a one-time procedure, but in complex cases, multiple open surgeries are often required to correct the baby’s head shape.

After endoscopic surgery, visits at certain intervals are required to fit a series of helmets to help shape your baby’s skull. If open surgery is done, no helmet is needed afterward.

Craniosynostosis surgical procedure

This surgery is done in the operating room under general anesthesia. This means your child will be asleep and will not feel pain.

Traditional surgery is called open repair. It includes these steps:

- The most common place for a surgical cut to be made is over the top of the head, from just above one ear to just above the other ear. The cut is usually wavy. Where the cut is made depends on the specific problem.

- A flap of skin, tissue, and muscle below the skin, and the tissue covering the bone are loosened and raised up so the surgeon can see the bone.

- A strip of bone is usually removed where two sutures connect. This is called a strip craniectomy. Sometimes, larger pieces of bone must also be removed. This is called synostectomy. Parts of these bones may be changed or reshaped when they are removed. Then, they are put back. Other times, they are not.

- Sometimes, bones that are left in place need to be shifted or moved.

- Sometimes, the bones around the eyes are cut and reshaped.

- Bones are fastened using a plate with screws that go into the skull. More and more surgeons are using resorbable plates and screws. The plates may expand as the skull grows.

Surgery usually takes 3 to 7 hours. Your child will probably need to have a blood transfusion during or after surgery to replace blood that is lost during the surgery.

A newer kind of surgery (endoscopic surgery) is used for some children. This type is usually done for children younger than 3 to 6 months old.

- The surgeon makes one or two small cuts in the scalp. Most times these cuts are each just 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) long. These cuts are made above the area where the bone needs to be removed.

- A tube (endoscope) is passed through the small cuts. The scope allows the surgeon to view the area being operated on. Special medical devices and a camera are passed through the endoscope. Using these devices, the surgeon removes some bone through the cuts.

- This surgery usually takes about 1 hour. There is much less blood loss with this kind of surgery.

- Most children need to wear a special helmet to protect their head for a period of time after surgery.

Children do best when they have this surgery when they are 3 months old. The surgery should be done before the child is 6 months old.

Craniosynostosis surgery risks

Risks for any surgery are:

- Breathing problems

- Infection, including in the lungs and urinary tract

- Blood loss (children having an open repair may need a transfusion)

- Reaction to medicines

Risks for craniosynostosis surgery are:

- Infection in the brain

- Bones connect together again, and more surgery is needed

- Brain swelling

- Damage to brain tissue

After the craniosynostosis surgical procedure

After surgery, your child will be taken to an intensive care unit (ICU). Your child will be moved to a regular hospital room after a day or two. Your child will stay in the hospital for 3 to 7 days.

- Your child will have a large bandage wrapped around the head. There will also be a tube going into a vein. This is called an IV.

- The nurses will watch your child closely.

- Tests will be done to see if your child lost too much blood during surgery. A blood transfusion will be given, if needed.

- Your child will have swelling and bruising around the eyes and face. Sometimes, the eyes may be swollen shut. This often gets worse in the first 3 days after surgery. It should be better by day 7.

- Your child should stay in bed for the first few days. The head of your child’s bed will be raised. This helps keep the swelling down.

Talking, singing, playing music, and telling stories may help soothe your child. Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is used for pain. Your doctor can prescribe other pain medicines if your child needs them.

Most children who have endoscopic surgery can go home after staying in the hospital one night.

Follow instructions on caring for your child at home.

What to expect at home

Swelling and bruising on your baby’s head will get better after 7 days. But swelling around the eyes may come and go for up to 3 weeks.

Your baby’s sleeping patterns may be different after getting home from the hospital. Your baby may be awake at night and sleep during the day. This should go away as your baby gets used to being at home.

Self-care

Your baby’s surgeon may prescribe a special helmet to be worn, starting 3 weeks after the surgery. This helmet has to be worn to help further correct the shape of your baby’s head.

- The helmet needs to be worn every day for the first year after surgery.

- It has to be worn at least 23 hours a day. It can be removed during bathing.

- Even if your child is sleeping or playing, the helmet needs to be worn.

Your child should not go to school or daycare for at least 2 to 3 weeks after the surgery.

You’ll be taught how to measure your child’s head size. You should do this each week as instructed.

Your child will be able to return to normal activities and diet. Make sure your child doesn’t bump or hurt the head in any way. If your child is crawling, you may want to keep coffee tables and furniture with sharp edges out of the way until your child recovers.

If your child is younger than 1, ask the surgeon if you should raise your child’s head on a pillow during sleeping to prevent swelling around the face. Try to get your child to sleep on the back.

Swelling from the surgery should go away in about 3 weeks.

To help control your child’s pain, use children’s acetaminophen (Tylenol) as your child’s doctor advises.

Wound care

Keep your child’s surgery wound clean and dry until the doctor says you can wash it. DO NOT use any lotions, gels, or cream to rinse your child’s head until the skin has completely healed. DO NOT soak the wound in water until it heals.

When you clean the wound, make sure you:

- Wash your hands before you start.

- Use a clean, soft washcloth.

- Dampen the washcloth and use antibacterial soap.

- Clean in a gentle circular motion. Go from one end of the wound to the other.

- Rinse the washcloth well to remove the soap. Then repeat the cleaning motion to rinse the wound.

- Gently pat the wound dry with a clean, dry towel or a washcloth.

- Use a small amount of ointment on the wound as recommended by the child’s doctor.

- Wash your hands when you finish.

When to call your doctor

Call your child’s doctor if your child:

- Has a temperature of 101.5ºF (40.5ºC)

- Is vomiting and cannot keep food down

- Is more fussy or sleepy

- Seems confused

- Seems to have a headache

- Has a head injury

Also call if the surgery wound:

- Has pus, blood, or any other drainage coming from it

- Is red, swollen, warm, or more painful

- Craniosynostosis Information Page. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Craniosynostosis-Information-Page

- Raposo-Amaral CE, Neto JG, Denadai R, Raposo-Amaral CM, Raposo-Amaral CA. Patient-reported quality of life in highest-functioning Apert and Crouzon syndromes: a comparative study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;133:182e–191e.

- Ghizoni E, Denadai R, Raposo-Amaral CA, Joaquim AF, Tedeschi H, Raposo-Amaral CE. Diagnosis of infant synostotic and nonsynostotic cranial deformities: a review for pediatricians. Diagnóstico das deformidades cranianas sinostóticas e não sinostóticas em bebês: uma revisão para pediatras. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2016;34(4):495‐502. doi:10.1016/j.rpped.2016.01.004 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5176072

- Massimi L, Caldarelli M, Tamburrini G, Paternoster G, Di Rocco C. Isolated sagittal craniosynostosis: definition, classification, and surgical indications. Childs Nerv Syst. 2012;28:1311–1317.

- McCarthy JG, Bradley JP, Stelnicki EJ, Stokes T, Weiner HL. Hung span method of scaphocephaly reconstruction in patients with elevated intracranial pressure. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;109:2009–2018.

- Raposo-Amaral CE, Denadai R, Takata JP, Ghizoni E, Buzzo CL, Raposo-Amaral CA. Progressive frontal morphology changes during the first year of a modified Pi procedure for scaphocephaly. Childs Nerv Syst. 2016;32:337–344.

- Raposo-Amaral CE, Denadai R, Ghizoni E, Buzzo CL, Raposo-Amaral CA. Facial changes after early treatment of unilateral coronal synostosis question the necessity of primary nasal osteotomy. J Craniofac Surg. 2015;26:141–146.

- Ghizoni E, Raposo-Amaral CA, Mathias R, Denadai R, Raposo-Amaral CE. Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis as a treatment complication of nonsyndromic Kleeblattschädel. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:2030–2033.

- Raposo-do-Amaral CE, Raposo-do-Amaral CA, Guidi MC, Buzzo CL. Prevalência do estrabismo na craniossinostose coronal unilateral. Há benefício com a cirurgia craniofacial? Rev Bras Cir Craniomaxilofac. 2010;13:73–77.

- Di Rocco C, Paternoster G, Caldarelli M, Massimi L, Tamburrini G. Anterior plagiocephaly: epidemiology, clinical findings, diagnosis, and classification. A review. Childs Nerv Syst. 2012;28:1413–1422.

- Van der Meulen J. Metopic synostosis. Childs Nerv Syst. 2012;28:1359–1367.

- Matushita H, Alonso N, Cardeal DD, Andrade FG. Major clinical features of synostotic occipital plagiocephaly: mechanisms of cranial deformations. Childs Nerv Syst. 2014;30:1217–1224.

- Tamburrini G, Caldarelli M, Massimi L, Gasparini G, Pelo S, Di Rocco C. Complex craniosynostoses: a review of the prominent clinical features and the related management strategies. Childs Nerv Syst. 2012;28:1511–1523.

- Nowinski D, Di Rocco F, Renier D, SainteRose C, Leikola J, Arnaud E. Posterior cranial vault expansion in the treatment of craniosynostosis. Comparison of current techniques. Childs Nerv Syst. 2012;28:1537–1544.

- Heuzé Y, Holmes G, Peter I, Richtsmeier JT, Jabs EW. Closing the gap: genetic and genomic continuum from syndromic to nonsyndromic craniosynostoses. Curr Genet Med Rep. 2014;2:135–145.