Crigler Najjar syndrome

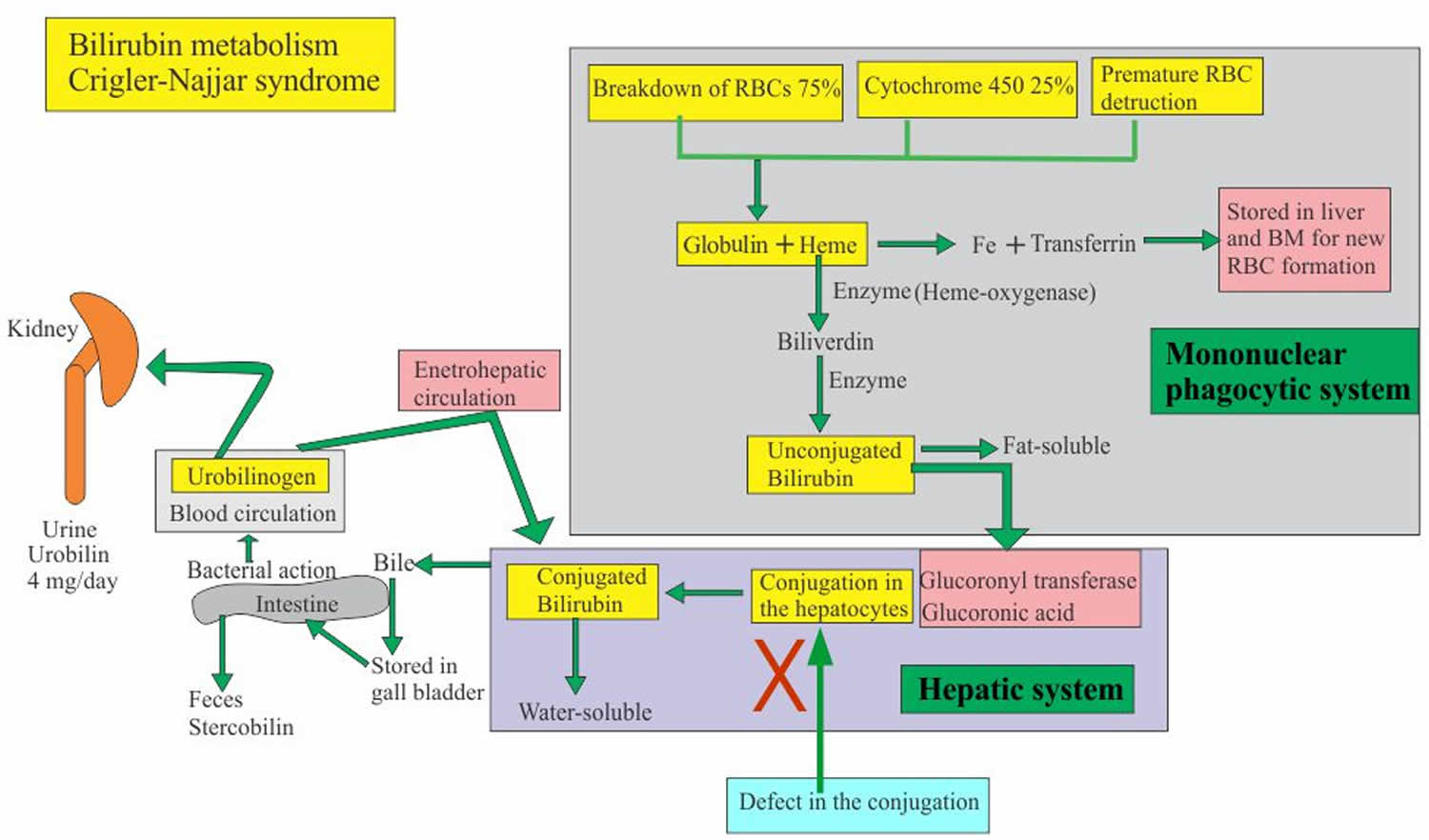

Crigler-Najjar syndrome is a very rare inherited disorder characterized by a persistent high levels of a toxic substance called unconjugated bilirubin in the blood (unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia). Bilirubin is the waste product of the breakdown of hemoglobin during the normal turnover of red blood cells (RBCs). Bilirubin is not soluble in water and before excretion in the bile must be associated (conjugated) with a substance called glucuronid acid. This process takes place in the liver thanks to the bilirubin-uridine diphosphoglucuronate glucuronosyltransferase, also known as UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1) enzyme. Crigler-Najjar syndrome is divided into two types. In Crigler-Najjar type 1 patients the uridine diphosphoglucuronate glucuronosyltransferase enzyme is inactive or severely reduced in Crigler-Najjar type 2. Therefore bilirubin cannot be excreted into the bile and remains in the blood. People with Crigler-Najjar syndrome have a buildup of unconjugated bilirubin in their blood (unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia). The high plasma level of unconjugated bilirubin (the toxic form of bilirubin) leads to jaundice and may lead to kernicterus (bilirubin encephalopathy) due to bilirubin toxicity. Crigler-Najjar type 1 (CN1) is very severe, and affected individuals can die in childhood due to kernicterus, although with proper treatment, they may survive longer. Crigler-Najjar type 2 (CN2) is less severe. People with Crigler-Najjar type 2 are less likely to develop kernicterus, and most affected individuals survive into adulthood.

Bilirubin has an orange-yellow tint, and hyperbilirubinemia causes yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes (jaundice). In Crigler-Najjar syndrome, jaundice is apparent at birth or in infancy. Severe unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia can lead to a condition called kernicterus, which is a form of brain damage caused by the accumulation of unconjugated bilirubin in the brain and nerve tissues. Babies with kernicterus are often extremely tired (lethargic) and may have weak muscle tone (hypotonia). These babies may experience episodes of increased muscle tone (hypertonia) and arching of their backs. Kernicterus can lead to other neurological problems, including involuntary writhing movements of the body (choreoathetosis), hearing problems, or intellectual disability.

Crigler-Najjar syndrome is estimated to affect fewer than 1 in 750,000-1,000,000 newborns worldwide 1. Many researchers believe that the disorder often goes undiagnosed or misdiagnosed making it difficult to determine its true frequency in the general population. It is likely more common than estimated.

Figure 1. Crigler-Najjar syndrome bilirubin metabolism

Crigler Najjar syndrome type 1

Crigler Najjar syndrome type 1 is an inherited disorder in which bilirubin, a substance made by the liver, cannot be broken down. Crigler Najjar syndrome type 1 occurs when the uridine diphosphoglucuronate glucuronosyltransferase enzyme that normally converts bilirubin into a form that can easily be removed from the body does not work correctly. Without this enzyme, bilirubin can build up in the body and lead to jaundice and damage to the brain, muscles, and nerves 2. Crigler Najjar syndrome, type 1 is caused by mutations in the UGT1A1 gene. The condition is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner 3. Treatment relies on regular phototherapy throughout life. Blood transfusions and calcium compounds have also been used. Liver transplantation may be considered in some individuals 2.

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 is a rare disorder that causes elevated levels of unconjugated bilirubin in the blood (unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia). Bilirubin normally is made by the body when old red blood cells are broken down. However, people with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 develop hyperbilirubinemia even when red blood cells are not excessively broken down, because they have too little of a liver uridine diphosphoglucuronate glucuronosyltransferase enzyme needed for conversion and excretion of bilirubin 4.

The main symptom of Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 is persistent jaundice, which is yellowing of the skin, mucous membranes and whites of the eyes. Jaundice may become noticeable in infancy (particularly when an infant is sick or has not eaten for an extended time), but some people with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 are not diagnosed until adulthood. Rarely, a person with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 may develop bilirubin encephalopathy (also called kernicterus), especially during illness, prolonged fasting, or while under anesthesia 4.

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 is caused by mutations in the UGT1A1 gene and inheritance is autosomal recessive. Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 responds to treatment with phenobarbital; however during an episode of severe hyperbilirubinemia, phototherapy may be needed. Not all people with CN-2 require treatment, but routine monitoring is still recommended 4.

Of note, mutations in the UGT1A1 gene can alternatively cause other disorders, such as Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 (CN-1) and Gilbert syndrome. Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 (CN-1) is characterized by near or complete absence of enzyme activity (versus partial absence in type 2) and severe, life-threatening symptoms. Phenobarbitol treatment is ineffective for people with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1, which is treated differently 4. Gilbert syndrome is considered a mild liver disorder that often does not cause symptoms or causes mild jaundice 5. Sometimes it can be hard to distinguish between Gilbert syndrome and Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 because of considerable overlap in measured bilirubin levels. Genetic testing to identify the specific mutation present is sometimes needed for the correct diagnosis 5.

Crigler Najjar syndrome causes

Mutations in the UGT1A1 gene cause Crigler-Najjar syndrome. The UGT1A1 gene contains instructions for creating (encoding) a liver enzyme known as uridine disphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase-1 (UGT1A1). The bilirubin uridine diphosphate glucuronosyl transferase (bilirubin-UGT) enzyme, which is found primarily in liver cells and is necessary for the removal of bilirubin from the body. This enzyme is required for the conversion (conjugation) and subsequent excretion of bilirubin from the body.

The bilirubin-uridine diphosphate glucuronosyl transferase (bilirubin-UGT) enzyme performs a chemical reaction called glucuronidation. During this reaction, the enzyme transfers a compound called glucuronic acid to unconjugated bilirubin, converting it to conjugated bilirubin. Glucuronidation makes bilirubin dissolvable in water so that it can be removed from the body.

Mutations in the UGT1A1 gene that cause Crigler-Najjar syndrome result in reduced or absent function of the bilirubin-UGT enzyme. People with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 have no enzyme function, while people with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 have less than 20 percent of normal function. The loss of bilirubin uridine diphosphate glucuronosyl transferase (bilirubin-UGT) function decreases glucuronidation of unconjugated bilirubin. This toxic substance then builds up in the body, causing unconjugated hyperbilirubinemia and jaundice.

Symptoms are caused by a complete or partial absence of bilirubin uridine diphosphate glucuronosyl transferase (bilirubin-UGT) enzyme, which results in the accumulation of unconjugated bilirubin in the body. Bilirubin circulates in the liquid portion of the blood (plasma) in conjunction with a protein called albumin; this is called unconjugated bilirubin, which does not dissolve in water (water-insoluble). Normally, this unconjugated bilirubin is taken up by the liver cells and, with the help of the UGT1A1 enzyme, converted to form water-soluble bilirubin glucuronides (conjugated bilirubin), which are then excreted in the bile. The bile is stored in the gall bladder and, when called upon, passes into the common bile duct and then into the upper portion of the small intestine (duodenum) and aids in digestion. Most bilirubin is eliminated from the body in the feces. When bilirubin levels increase high enough, it can eventually cross the blood-brain barrier, infiltrating brain tissue and causing the neurological symptoms sometimes associated with Crigler-Najjar syndrome.

Parents of children with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 may exhibit some defects in bilirubin metabolism; however, they do not display any physical findings of this disorder because they are have only one copy (heterozygous) of the altered UGT1A1 gene).

Crigler-Najjar syndrome inheritance pattern

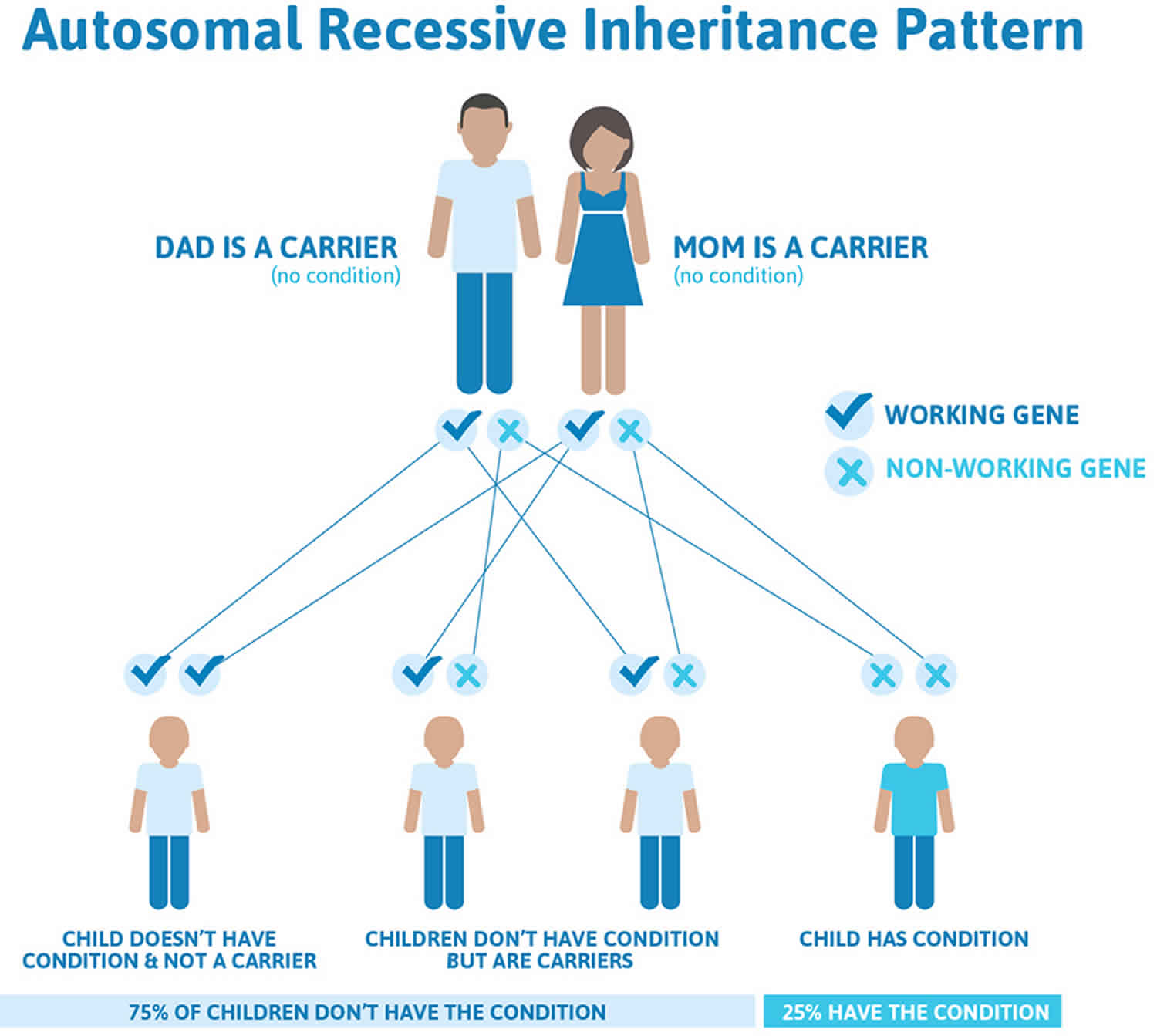

Crigler-Najjar syndrome is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern, which means both copies of the UGT1A1 gene in each cell have mutations. A less severe condition called Gilbert syndrome can occur when one copy of the UGT1A1 gene has a mutation.

It is rare to see any history of autosomal recessive conditions within a family because if someone is a carrier for one of these conditions, they would have to have a child with someone who is also a carrier for the same condition. Autosomal recessive conditions are individually pretty rare, so the chance that you and your partner are carriers for the same recessive genetic condition are likely low. Even if both partners are a carrier for the same condition, there is only a 25% chance that they will both pass down the non-working copy of the gene to the baby, thus causing a genetic condition. This chance is the same with each pregnancy, no matter how many children they have with or without the condition.

- If both partners are carriers of the same abnormal gene, they may pass on either their normal gene or their abnormal gene to their child. This occurs randomly.

- Each child of parents who both carry the same abnormal gene therefore has a 25% (1 in 4) chance of inheriting a abnormal gene from both parents and being affected by the condition.

- This also means that there is a 75% ( 3 in 4) chance that a child will not be affected by the condition. This chance remains the same in every pregnancy and is the same for boys or girls.

- There is also a 50% (2 in 4) chance that the child will inherit just one copy of the abnormal gene from a parent. If this happens, then they will be healthy carriers like their parents.

- Lastly, there is a 25% (1 in 4) chance that the child will inherit both normal copies of the gene. In this case the child will not have the condition, and will not be a carrier.

These possible outcomes occur randomly. The chance remains the same in every pregnancy and is the same for boys and girls.

Figure 2 illustrates autosomal recessive inheritance. The example below shows what happens when both dad and mum is a carrier of the abnormal gene, there is only a 25% chance that they will both pass down the abnormal gene to the baby, thus causing a genetic condition.

Figure 2. Crigler-Najjar syndrome autosomal recessive inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Crigler Najjar syndrome symptoms

Crigler-Najjar syndrome symptoms may include:

- Confusion and changes in thinking

- Yellow skin (jaundice) and yellow in the whites of the eyes (icterus), which begin a few days after birth and get worse over time

- Lethargy

- Poor feeding

- Vomiting

Crigler-Najjar syndrome is manifested by severe, persistent jaundice, a condition in which the skin and the whites of the eyes become yellow. This is due to excessive plasmatic levels of bilirubin (> 20 mg/dL in Crigler-Najjar type I patients). Whether untreated severe jaundice may result in brain damage (kernicterus) with possible permanent effects. As results of brain damage clinical manifestations of kernicterus include hypotonia, lethargy, deafness, oculomotor palsy. The symptoms of Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 become apparent shortly after birth. Affected infants develop severe, persistent yellowing of the skin, mucous membranes and whites of the eyes (jaundice). These symptoms persist after the first three weeks of life.

Infants are at risk for developing kernicterus, also known as bilirubin encephalopathy, within the first month of life. Kernicterus is a potentially life-threatening neurological condition in which toxic levels of bilirubin accumulate in the brain, causing damage to the central nervous system. Early signs of kernicterus may include lack of energy (lethargy), vomiting, fever, and/or unsatisfactory feedings. Other symptoms that may follow include absence of certain reflexes (Moro reflex); mild to severe muscle spasms, including spasms in which the head and heels are bent or arched backward and the body bows forward (opisthotonus); and/or uncontrolled involuntary muscle movements (spasticity). In addition, affected infants may suck or nurse weakly, develop a high-pitched cry, and/or exhibit diminished muscle tone (hypotonia), resulting in abnormal “floppiness.”

Kernicterus can result in milder symptoms such as clumsiness, difficulty with fine motor skills and underdevelopment of the enamel of teeth, or it can result in severe complications such as hearing loss, problems with sensory perception, convulsions, and slow, continuous, involuntary, writhing movements (athetosis) of the arms and legs or the entire body. An episode of kernicterus can ultimately result in life-threatening brain damage.

Although kernicterus usually develops early during infancy, in some cases, individuals with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 may not develop kernicterus until later during childhood or in early adulthood. Patients in whom the blood bilirubin concentration is maintained at safe levels by exposure to light (see below under treatment) can develop kernicterus at any age if the light treatment is interrupted or the patient is affected by other illnesses.

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 is a milder disorder than type 1. Affected infants develop jaundice, which increases during times when an infant is sick (concurrent illness), has not eaten for an extended period of time (prolonged fasting) or is under general anesthesia. Some people have not been diagnosed until they are adults. Kernicterus is rare in Crigler-Najjar syndrome type II, but can occur especially when an affected individual is sick, not eating or under anesthesia.

Crigler Najjar syndrome diagnosis

A diagnosis may be suspected within the first few days of life in infants with persistent jaundice. A diagnosis may be confirmed by a thorough clinical evaluation, characteristic findings, detailed patient history, and specialized testing. For example, in infants with this disorder, blood tests reveal abnormally high levels of unconjugated bilirubin in the absence of increased levels of red blood cell degeneration (hemolysis), as in Rh disease (isoimmunization). In addition, bile analysis reveals no detectable bilirubin glucuronides and urine analysis may demonstrate a lack of bilirubin.

Molecular genetic testing can confirm a diagnosis of Crigler-Najjar syndrome. Molecular genetic testing can detect mutations in the UGT1A1 gene that are known to cause the disorder, but is available only as a diagnostic service at specialized laboratories.

It is important to distinguish Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 and type 2. The administration of phenobarbital, a barbiturate, reduces blood bilirubin levels individuals affected with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 and Gilbert syndrome, but is ineffective for those with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1. Therefore, failure to respond to this medication is an important indication for differential diagnostic purposes.

Crigler Najjar syndrome treatment

Treatment is directed toward lowering the level of unconjugated bilirubin in the blood. Early treatment is imperative in Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 to prevent the development of kernicterus during the first few months of life. Because Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 is milder and responds to phenobarbital, treatment is different.

The mainstay of treatment for Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 is aggressive phototherapy. During this procedure, the bare skin is exposed to intense light, while the eyes are shielded. This helps to change the bilirubin molecules in the skin, so that it can be excreted in bile without conjugation. As affected individuals age, the body mass increases and the skin thickens, making phototherapy less effective for preventing kernicterus. For years, fluorescent light has been used, but has drawbacks including exposing patients to ultraviolet radiation. Some doctors recommend using light-emitting diodes (LEDs) technology, which uses blue light. This technology can be adjusted to the specific treatment level needed in an individual and does not expose people to ultraviolet radiation. However, it is not widely available. Exposure of skin to sun light is very effective in reducing blood bilirubin levels.

Infections, episodes of fevers, and other types of illnesses should be treated immediately to reduce the risk of an affected individual developing kernicterus.

Plasmapherersis has been used to rapidly lower bilirubin levels in the blood. Plasmapheresis is a method for removing unwanted substances (toxins, metabolic substances and plasma components) from the blood. During plasmapheresis, blood is removed from the affected individual and blood cells are separated from plasma. The plasma is then replaced with other human plasma and the blood is transfused back into the affected individual.

Liver transplantation is the only definitive treatment for individuals with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1. Liver transplantation has drawbacks such as cost, limited availability of a donor, need for prolonged use of immunosuppressive drugs and the potential of rejection. Some physicians recommend a liver transplant if infants or children with severely elevated levels of unconjugated bilirubin do not respond to other therapy (refractory hyperbilirubinemia) or if there is a progression of neurological symptoms. Other physicians believe that liver transplantation should be performed before adolescence as preventive therapy, before brain damage can result from early onset kernicterus.

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 responds to treatment with phenobarbital. In some instances, during an episode of severe hyperbilirubinemia, individuals with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 may need phototherapy. Some affected individuals may not require any treatment, but should be monitored routinely.

Genetic counseling is recommended for affected individuals and their families. Psychosocial support for the entire family is essential as well. Other treatment is symptomatic and supportive.

Investigational therapies

Research on inborn errors of metabolism such as Crigler-Najjar syndrome is ongoing. Scientists are studying the causes of these disorders and attempting to design enzyme replacement therapies (ERT) that may return missing and/or deficient enzymes to the body. Enzyme replacement therapy has been successful in treating other metabolic disorders and research is underway to develop an enzyme replacement therapy for Crigler-Najjar syndrome.

Gene therapy is also being studied as another approach to therapy for individuals with Crigler-Najjar syndrome. In gene therapy, the defective gene present in a patient is replaced with a normal gene to enable the production of the active enzyme and prevent the development and progression of the disease in question. Gene transfer could be permanent, leading to life-long cure of the disease. However, at this time, some technical difficulties need to be resolved before this type of gene therapy can be advocated. Other types of gene transfer that can reduce the bilirubin levels for several years, but not lifelong, is being considered for the treatment of Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1.

Researchers are studying whether the transplantation of liver cells (hepatocytes) are beneficial as a treatment of Crigler-Najjar syndrome. Because the liver is structurally sound in individuals with Crigler-Najjar syndrome, researchers are exploring the possibility that transplanting hepatocytes may provide partial correction of the UGT1A1 enzyme deficiency. More studies are needed to determine the long-term effectiveness of this treatment. Like liver transplantation, transplantation of hepatocytes requires prolonged treatment with immunosuppressive drugs.

Crigler Najjar syndrome prognosis

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1

Kernicterus in infancy or later in life is the main cause of death in Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1. This disease can also result in permanent neurologic complications, due to bilirubin encephalopathy. Even with treatment, most, if not all, patients with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 eventually develop some neurologic deficit.

Unless treated vigorously (ie, orthotopic liver transplant, segmental transplantation), most patients with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 die by age 15 months. Fortunately, more patients are surviving to adulthood because of advances in the treatment of hyperbilirubinemia.

Neonates of mothers with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1 develop adverse outcomes, including developmental delay, hearing loss, and cerebellar syndrome 6.

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2

Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2 form of this disease runs a more benign clinical course than Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 1, several cases of bilirubin-induced brain damage have been reported. (Bilirubin encephalopathy occurs usually when patients experience a superimposed infection or stress.) With proper treatment, however, neurologic sequelae can be avoided.

In neonates of mothers with Crigler-Najjar syndrome type 2, the use of phenobarbital in pregnancy appears to be safe, with good fetal and maternal outcome 6.

References- Crigler-Najjar syndrome. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/crigler-najjar-syndrome

- Crigler-Najjar syndrome. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001127.htm

- UGT1A1 gene. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/gene/UGT1A1

- Crigler Najjar Syndrome. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/crigler-najjar-syndrome

- Wagner K-H, Shiels RG, Lang CA, Khoei NS, Bulmer AC. Diagnostic criteria and contributors to Gilbert’s syndrome. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences. 2018; 55(2):129-139. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29390925

- Sagili H, Pramya N, Jayalaksmi D, Rani R. Crigler-Najjar syndrome II and pregnancy outcome. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2012 Feb. 32(2):188-9.