What is cysticercosis

Cysticercosis is a parasitic tissue infection caused by the larvae of the pork tapeworm Taenia solium 1. These larvae cysts infect brain (cerebral cysticercosis or neurocysticercosis), muscle, eye (ocular cysticercosis) or other tissue, and are a major cause of adult onset seizures in most low-income countries. A person gets cysticercosis by swallowing tapeworm eggs found in the feces, which can be found in contaminated food, of a person who has an intestinal tapeworm. People living in the same household with someone who has a tapeworm have a much higher risk of getting cysticercosis than people who don’t.

In most cases, the pork tapeworms (Taenia solium) stay in the muscles and do not cause symptoms. However, symptoms may be present when the infection is found in the brain, eyes, heart or spine.

People do not get cysticercosis by eating undercooked pork. Eating undercooked pork can result in intestinal tapeworm if the pork contains larval cysts. Pigs become infected by eating tapeworm eggs in the feces of a human infected with a tapeworm.

Human cysticercosis is found worldwide, especially in areas where pig cysticercosis is common. Both taeniasis and cysticercosis are most often found in rural areas of developing countries with poor sanitation, where pigs roam freely and eat human feces. Taeniasis and cysticercosis are rare among persons who live in countries where pigs are not raised and in countries where pigs do not have contact with human feces. Although uncommon, cysticercosis can occur in people who have never traveled outside of the United States if they are exposed to tapeworm eggs.

Although rare in the United States, cysticercosis is common in many developing countries. Both the tapeworm infection, also known as taeniasis, and cysticercosis occur globally. The highest rates of infection are found in areas of Latin America, Asia, and Africa that have poor sanitation and free-ranging pigs that have access to human feces. Although uncommon, cysticercosis can occur in people who have never traveled outside of the United States. For example, a person infected with a tapeworm who does not wash his or her hands might accidentally contaminate food with tapeworm eggs while preparing it for others.

Taenia solium is found worldwide. Because pigs are intermediate hosts of the parasite, completion of the life cycle occurs in regions where humans live in close contact with pigs and eat undercooked pork. Taeniasis and cysticercosis are very rare in Muslim countries. It is important to note that human cysticercosis is acquired by ingesting Taenia solium eggs shed in the feces of a human Taenia solium tapeworm carrier, and thus can occur in populations that neither eat pork nor share environments with pigs.

The symptoms of cysticercosis are caused by the development of cysticerci in various sites. Of greatest concern is brain cysticercosis (cerebral cysticercosis or neurocysticercosis) caused the larval cysts of the pork tapeworm in the central nervous system, which can cause diverse manifestations including seizures, mental disturbances, focal neurologic deficits, and signs of space-occupying intracerebral lesions. Death can occur suddenly. The resulting signs and symptoms depend on the number, location, size, and stage (viable, degenerating, or calcified) of the cysticerci and the intensity of the host inflammatory response to degenerating cysts. Seizures are the most common manifestation, present in 70-90% of symptomatic patients in published case series. Less frequent clinical manifestations include intracranial hypertension, hydrocephalus, chronic meningitis, and cranial nerve abnormalities.

Extracerebral cysticercosis can cause ocular, cardiac, or spinal lesions with associated symptoms. Asymptomatic subcutaneous nodules and calcified intramuscular nodules can be encountered.

Treatment may include medications to kill the parasites and powerful anti-inflammatory medications (steroids) to reduce swelling. In severe cases, surgery may be needed to remove the infected area 2.

Figure 1. Taenia solium (pork tapeworm)

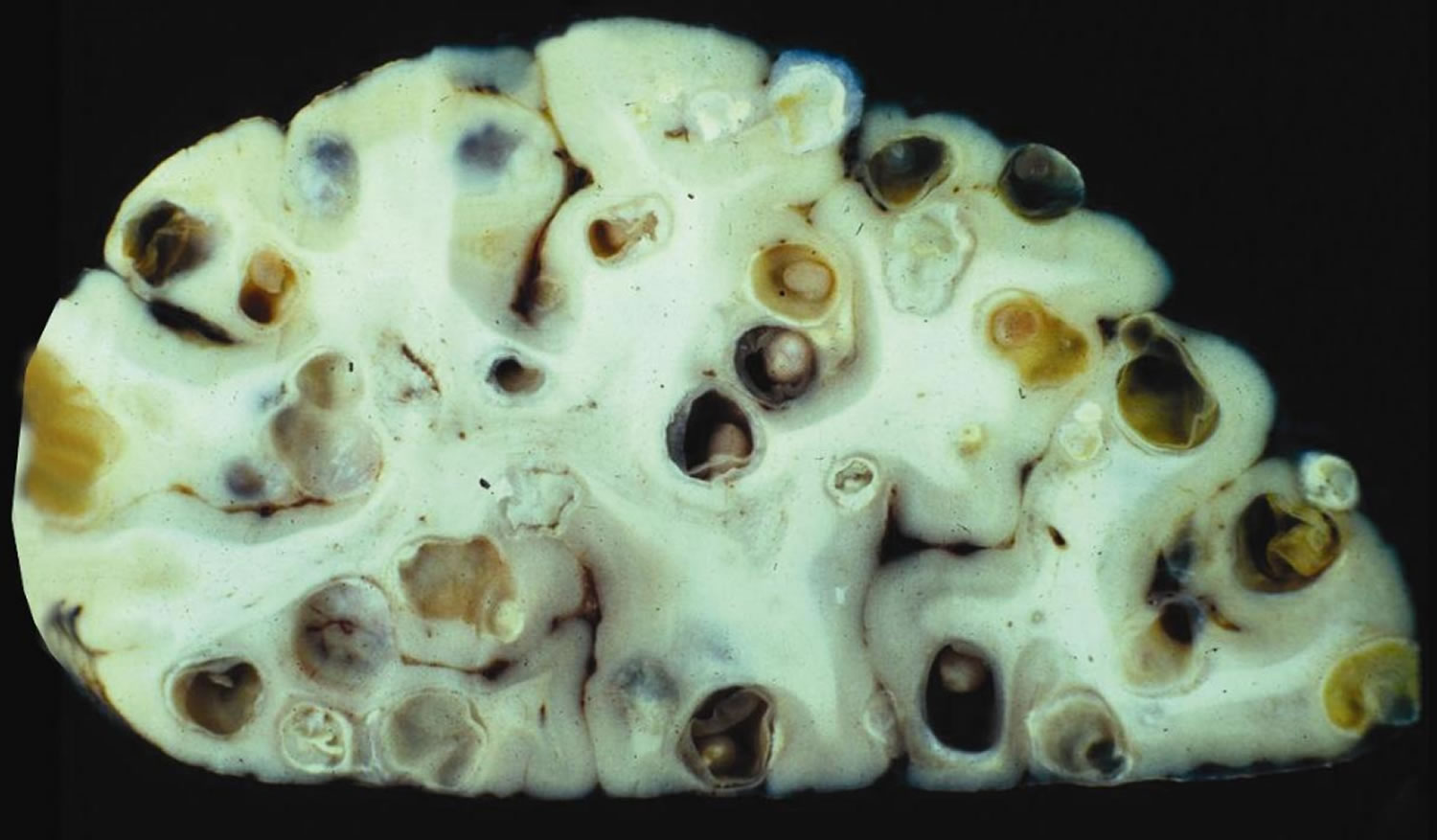

Figure 3. Brain cysticercosis

Cysticercosis life cycle

The larval form (cysticercus) of the pork tapeworm (Taenia solium) life cycle.

Cysticercosis is an infection of both humans and pigs with the larval stages of the parasitic cestode, Taenia solium. This infection is caused by ingestion of eggs shed in the feces of a human tapeworm carrier (#1). Pigs and humans become infected by ingesting eggs or gravid proglottids (#2 and #7). Humans are infected either by ingestion of food contaminated with feces, or by autoinfection. In the latter case, a human infected with adult Taenia solium can ingest eggs produced by that tapeworm, either through fecal contamination or, possibly, from proglottids carried into the stomach by reverse peristalsis. Once eggs are ingested, oncospheres hatch in the intestine (#3 and #8) invade the intestinal wall, and migrate to striated muscles, as well as the brain, liver, and other tissues, where they develop into cysticerci. In humans, cysts can cause serious complications if they localize in the brain, resulting in neurocysticercosis. The parasite life cycle is completed, resulting in human tapeworm infection, when humans ingest undercooked pork containing cysticerci (#4). Cysts evaginate and attach to the small intestine by their scolex (#5). Adult tapeworms develop, (up to 2 to 7 m in length and produce less than 1000 proglottids, each with approximately 50,000 eggs) and reside in the small intestine for years (#6).

Figure 4. Cysticercosis life cycle

Cysticercosis causes

Cysticercosis is caused by swallowing eggs from Taenia solium. The eggs are found in contaminated food. Autoinfection is when a person who is already infected with adult Taenia solium swallows its eggs. This occurs due to improper hand washing after a bowel movement.

A person with an adult tapeworm (Taenia solium), which lives in the person’s gut, sheds eggs in the stool. The infection with the adult tapeworm is called taeniasis. A pig then eats the eggs in the stool. The eggs develop into larvae inside the pig and form cysts (called cysticerci) in the pig’s muscles or other tissues. The infection with the cysts is called cysticercosis. Humans who eat undercooked or raw infected pork swallow the Taenia solium cysts in the meat. The larvae then come out of their cysts in the human gut and develop into adult tapeworms, completing the cycle.

People get cysticercosis when they swallow eggs that are excreted in the stool of people with the adult tapeworm. This may happen when people

- Drink water or eat food contaminated with tapeworm eggs

- Put contaminated fingers in their mouth

Cysticercosis is not spread by eating undercooked meat. However, people get infected with tapeworms (taeniasis) by eating undercooked infected pork. People who have tapeworm infections can infect themselves with the eggs and develop cysticercosis (this is called autoinfection). They can also infect other people if they have poor hygiene and contaminate food or water that other people swallow. People who live with someone who has a tapeworm infection in their intestines have a much higher risk of getting cysticercosis than other people.

The period between initial infection and symptom onset varies from several months to many years.

Risk factors include eating pork, fruits, and vegetables contaminated with Taenia solium as a result of undercooking or improper food preparation. Cysticercosis can also be spread by contact with infected feces.

Cysticercosis is rare in the United States. It is common in many developing countries. In the United States, infections are detected predominantly in immigrants from Mexico, Guatemala, and other Latin American countries who acquired their infections in their home country. However, taeniasis and cysticercosis occur globally, with the highest rates in areas of Latin America, Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa with poor sanitation and free-ranging pigs with access to human feces.

Clusters and sporadic cases of cysticercosis acquired in the U.S. have been reported. Food handlers with taeniasis are of particular concern in this scenario (see prevention/control section for more information).

In humans, cysticerci (encysted larvae) often occur in skeletal muscles. However, the manifestations that most frequently lead patients to visit health care providers are caused by cysts in the central nervous system (CNS), known as neurocysticercosis. Less frequently, cysticerci may localize in the eyes, skin, or heart.

Cysticercosis prevention

Avoid unwashed foods, do not eat uncooked foods while traveling, and always wash fruits and vegetables well.

To prevent cysticercosis, the following precautions should be taken:

- Wash your hands with soap and warm water after using the toilet, changing diapers, and before handling food

- Teach children the importance of washing hands to prevent infection

- Wash and peel all raw vegetables and fruits before eating

- Use good food and water safety practices while traveling in developing countries such as:

- Drink only bottled or boiled (1 minute) water or carbonated (bubbly) drinks in cans or bottles

- Filter unsafe water through an “absolute 1 micron or less” filter AND dissolve iodine tablets in the filtered water; “absolute 1 micron” filters can be found in camping and outdoor supply stores

The control and prevention of cysticercosis depends on preventing fecal-oral transmission of eggs from persons with taeniasis. Follow-up of cysticercosis cases reported to the Los Angeles County Health Department from 1988 to 1991 demonstrated at least one active tapeworm carrier among family contacts of 22% of locally acquired cases, and 5% of imported cases. Identification and treatment of tapeworm carriers is an important public health measure that can prevent further cases.

When traveling to areas with poor sanitation, persons should be particularly careful to avoid foods that might be contaminated by human feces. Food handlers should be educated in good handwashing practices. Based on investigations of cases of neurocysticercosis in U.S. citizens who acquired their infections from asymptomatic household employees from Latin America, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that such employees should have stool examinations for taeniasis and be treated if found to be infected. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) does not recommend the routine testing of commercial food handlers, but does support policies aimed at ensuring that food handlers are taught and adhere to good handwashing practices.

Cysticercosis symptoms

Most often, the pork tapeworms (Taenia solium) stay in muscles and do not cause symptoms.

Symptoms that do occur depend on where the infection is found in the body:

- Brain cysticercosis

- May cause no symptoms

- May cause seizures and/or headaches (these are more common), similar to those of a brain tumor

- May also cause confusion, difficulty with balance, brain swelling, and excess fluid around the brain (these are less common)

- May cause stroke or death

- Eyes cysticercosis — decreased vision or blindness

- Heart cysticercosis — abnormal heart rhythms or heart failure (rare)

- Spine cysticercosis — weakness or changes in walking due to damage to nerves in the spine

- Muscle cysticercosis

- Generally do not cause symptoms

- May cause lumps under the skin, which can sometimes become tender

Brain cysticercosis or cerebral cysticercosis

Neurocysticercosis refers to a condition in which cysticercosis affects the brain and spinal cord. Neurocysticercosis may be parenchymal (occurring in the brain substance, the most common location) or extraparenchymal (occurring in the meninges, the ventricles, the basilar cisterns, or the subarachnoid space of the brain or spinal cord).

The symptoms of neurocysticercosis depend on the number, location, size, and stage (viable, degenerating, or calcified) of the cysticerci and the intensity of the inflammatory response to degenerating cysts. Seizures and headaches are the most common manifestation, present in 70-90% of symptomatic patients in published case series. Less frequent clinical manifestations include confusion, inattentiveness, difficulty with balance, intracranial hypertension, swelling of the brain (hydrocephalus), chronic meningitis, and cranial nerve abnormalities, may also occur. Death may occur with more severe infections.

The number of cysticerci in the host can vary from one to more than 1,000. In the absence of massive numbers of cysticerci, the initial host tissue reaction is usually minimal. The developing cysticercus affects the surrounding tissue as a slowly growing mass that may cause pressure atrophy. Most live cysts do not cause an inflammatory reaction, but an acute inflammatory response occurs when the cysts degenerate, which results in the release of parasite antigens. Degeneration of a cyst may occur years after the initial infection. Some calcified cysts may intermittently release antigen, though this process is not fully understood. In the CNS, the inflammatory reaction and resultant edema appear as a contrast-enhancing ring around the cyst on imaging. There may be CSF pleocytosis as well. Necrotic larvae are completely or partially resorbed, but may become calcified, resulting in focal scarring that may provide a focus for seizures.

The distinction between parenchymal and extraparenchymal neurocysticercosis has important prognostic implications. Parenchymal disease with small numbers of cysts carries an excellent long-term prognosis (probably even without anthelminthic therapy) compared to parenchymal disease with > 50 cysts and extraparenchymal disease.

Diagnosis usually involves both serological testing and brain imaging.

Treatment might be recommended in certain cases of neurocysticercosis and depend on the number and location of cysts. For example, treatment might not be necessary for cases in which only one cysticeri is found. On the other hand, a person who has multiple cysticeri that are not calcified (i.e. dead) may require anti-parasitic treatment. Usually neurological symptoms such as swelling subside if the cysticeri die and shrink 3.

The most urgent therapeutic interventions are aimed at managing the neurological complications, and may require anticonvulsant therapy, corticosteroids, neurosurgical intervention and/or treatment of increased intracranial pressure. Anthelminthic treatment may be indicated, but must be administered with caution, because larval death provokes an inflammatory response that may increase symptoms. Concomitant steroids are usually indicated.

Cysticercosis possible complications

Cysticercosis complications may include:

- Blindness, decreased vision

- Heart failure or abnormal heart rhythm

- Hydrocephalus (fluid buildup in part of the brain, often with increased pressure)

- Seizures

Cysticercosis diagnosis

If you think that you may have cysticercosis, please see your health care provider. Your health care provider will ask you about your symptoms, where you have traveled, and what kinds of foods you eat. The diagnosis of neurocysticercosis usually requires MRI or CT brain scans. Blood tests may be useful to help diagnose an infection, but they may not always be positive in light infections.

Tests that may be done include:

- Blood tests to detect antibodies to the parasite

- Biopsy of the affected area

- CT scan, MRI scan, or x-rays to detect the lesion

- Spinal tap (lumbar puncture)

- Test in which an ophthalmologist looks inside the fundus of the eye

Diagnosis typically requires both CNS (central nervous system) imaging and serological testing. A careful history should be taken, including questions regarding residence or extended travel in developing countries, and consumption of food prepared by someone who has lived in a high-risk area.

Diagnosis often requires both imaging and serological testing because:

- A patient may have clinical disease from a single or very few cysticerci. In this instance, serological results may be negative, but the lesions may be visible on imaging.

- A patient may have cysticerci in locations other than the brain. In this instance, CNS imaging is negative but serological results might be positive, indicating an antibody response to lesions elsewhere (e.g. the spinal cord).

- The location and characteristics of the lesions on imaging, especially on MRI, are essential to determine the best treatment modalities.

Computerized tomography (CT) is superior to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for demonstrating small calcifications. However, MRI shows cysts in some locations (cerebral convexity, ventricular ependyma) better than CT, is more sensitive than CT to demonstrate surrounding edema, and may show internal changes indicating the death of cysticerci.

In recent years, the use of CT and MRI has permitted identification of neurocysticercosis cases with a benign course that would not have been detected previously. It is now recognized that most infections are asymptomatic, or mildly symptomatic and benign. Mortality is low in patients with parenchymal cysts or calcification without hydrocephalus. However, untreated cysticercosis with hydrocephalus, large basilar or supratentorial cysts, massive numbers of cysts, intracranial hypertension, or cerebral infarction can be life-threatening.

There are two available serologic tests to detect cysticercosis, the enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot (EITB), and commercial enzyme-linked immunoassays. The immunoblot is the test preferred by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), because its sensitivity and specificity have been well characterized in published analyses.

At least one commercial laboratory offers enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot testing. For confirmatory testing in cases where enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot is not available, contact the CDC directly. Cysticercosis is a reportable disease in several states. Health care providers should check with their state health department to determine if they require notification of patients testing positive for cysticercosis.

If you have been diagnosed with cysticercosis, you and your family members should be tested for intestinal tapeworm infection.

Cysticercosis treatment

Treatment may involve:

- Medicines to kill the parasites, such as albendazole or praziquantel

- Powerful anti-inflammatories (steroids) to reduce swelling

If the cyst is in the eye or brain, steroids should be started a few days before other medicines to avoid problems caused by swelling during antiparasitic treatment. Not all people benefit from antiparasitic treatment.

Sometimes, surgery may be needed to remove the infected area.

Brain cysticercosis treatment

The choice of treatment for neurocysticercosis depends on the clinical manifestations and the location, number, size, and stage of cysticerci. Anthelminthic chemotherapy for symptomatic neurocysticercosis is almost never a medical emergency. The focus of initial therapy is control of seizures, edema, intracranial hypertension, or hydrocephalus, when one of these conditions is present. Under certain circumstances, a ventricular shunt or other neurosurgical procedure may be indicated. Rarely, neurocysticercosis — especially large and/or subarachnoid (racemose) lesions — may present with imminent threat of intracranial herniation, a neurosurgical emergency.

Anthelminthic therapy, because it kills viable cysts and provokes an inflammatory response, may actually increase symptoms acutely. Co-administration of corticosteroids that cross the blood brain barrier (e.g. dexamethasone) is used to mitigate these effects. Recent placebo-controlled trials confirm that albendazole treatment in appropriately selected neurocysticercosis patients is effective in decreasing the frequency of generalized seizures in long-term follow-up.

Although the heterogeneity of the clinical picture of neurocysticercosis requires individual tailoring of treatment and management, several general principles apply:

- Anthelminthic therapy is generally indicated for symptomatic patients with multiple, live (noncalcified) cysticerci.

- Anthelminthic treatment will not benefit patients with dead worms (calcified cysts).

- Concomitant administration of steroids (e.g. dexamethasone) is often indicated to suppress the inflammatory response induced by destruction of live cysticerci.

- Conventional anticonvulsant therapy is the mainstay of management of neurocysticercosis-associated seizure disorders.

- Intraventricular cysts should usually be treated by surgical removal (endoscopic if possible). Anthelminthics are relatively contraindicated, because the resulting inflammatory response could precipitate obstructive hydrocephalus.

- Although our understanding of subarachnoid neurocysticercosis is evolving, treatment with both anthelminthics and corticosteroids is usually required.

- Ventricular shunting is often necessary as well.

Even when anthelminthic therapy is successful, continued use of anticonvulsant and other symptomatic medications may still be needed because the pathology may be irreversible. Decisions regarding discontinuation of anticonvulsant regimens must be made on an individual clinical basis, but data suggest that many patients can be eventually weaned from anticonvulsant therapy.

Medications

Several studies suggest that albendazole (conventional dosage 15 mg/kg/day in 2 divided doses for 15 days) may be superior to praziquantel (50 mg/kg/day for 15 days) for the treatment of neurocysticercosis. In comparative clinical trials, albendazole was equivalent or superior to praziquantel in reducing the number of live cysticerci. A recent placebo-controlled, double-blinded trial demonstrated that albendazole treatment (400 mg twice daily plus 6 mg dexamethasone QD for 10 days) significantly decreased generalized seizures over 30 months of follow-up.

More prolonged treatment courses (e.g. 30 days of albendazole, which may be repeated) may be needed for extraparenchymal or extensive disease. Albendazole is more likely to be effective against extraparenchymal forms of the disease because of better penetration than praziquantel into the CSF. Another possible contributing factor to the greater efficacy of albendazole is that serum and CSF metabolite levels appear to be potentiated by concomitant corticosteroids, whereas praziquantel levels are depressed. Albendazole, unlike praziquantel, has been reported to be effective in giant subarachnoid cysticerci (racemose cysts) and in extraocular muscle cysts. Both drugs appear to have a role in therapy, since cases that have not responded to one of the drugs have been reported to respond to the other.

Oral albendazole is available for human use in the United States. Oral praziquantel is available for human use in the United States.

Albendazole

- Note on Treatment in Pregnancy

- Albendazole is pregnancy category C. Data on the use of albendazole in pregnant women are limited, though the available evidence suggests no difference in congenital abnormalities in the children of women who were accidentally treated with albendazole during mass prevention campaigns compared with those who were not. In mass prevention campaigns for which the World Health Organization (WHO) has determined that the benefit of treatment outweighs the risk, WHO allows use of albendazole in the 2nd and 3rd trimesters of pregnancy. However, the risk of treatment in pregnant women who are known to have an infection needs to be balanced with the risk of disease progression in the absence of treatment.

- Pregnancy Category C: Either studies in animals have revealed adverse effects on the fetus (teratogenic or embryocidal, or other) and there are no controlled studies in women or studies in women and animals are not available. Drugs should be given only if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus.

- Note on Treatment During Lactation

- It is not known whether albendazole is excreted in human milk. Albendazole should be used with caution in breastfeeding women.

- Note on Treatment in Pediatric Patients

- The safety of albendazole in children less than 6 years old is not certain. Studies of the use of albendazole in children as young as one year old suggest that its use is safe. According to WHO guidelines for mass prevention campaigns, albendazole can be used in children as young as 1 year old. Many children less than 6 years old have been treated in these campaigns with albendazole, albeit at a reduced dose.

Praziquantel

- Note on Treatment in Pregnancy

- Praziquantel is pregnancy category B. There are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. However, the available evidence suggests no difference in adverse birth outcomes in the children of women who were accidentally treated with praziquantel during mass prevention campaigns compared with those who were not. In mass prevention campaigns for which the World Health Organization (WHO) has determined that the benefit of treatment outweighs the risk, WHO encourages the use of praziquantel in any stage of pregnancy. For individual patients in clinical settings, the risk of treatment in pregnant women who are known to have an infection needs to be balanced with the risk of disease progression in the absence of treatment.

- Pregnancy Category B: Either animal-reproduction studies have not demonstrated a fetal risk but there are no controlled studies in pregnant women or animal-reproduction studies have shown an adverse effect (other than a decrease in fertility) that was not confirmed in controlled studies in women in the first trimester (and there is no evidence of a risk in later trimesters).

- Note on Treatment During Lactation

- Praziquantel is excreted in low concentrations in human milk. According to WHO guidelines for mass prevention campaigns, the use of praziquantel during lactation is encouraged. For individual patients in clinical settings, praziquantel should be used in breast-feeding women only when the risk to the infant is outweighed by the risk of disease progress in the mother in the absence of treatment.

- Note on Treatment in Pediatric Patients

- The safety of praziquantel in children aged less than 4 years has not been established. Many children younger than 4 years old have been treated without reported adverse effects in mass prevention campaigns and in studies of schistosomiasis. For individual patients in clinical settings, the risk of treatment of children younger than 4 years old who are known to have an infection needs to be balanced with the risk of disease progression in the absence of treatment.