Dead arm syndrome

Dead arm syndrome also called recurrent transient subluxation of the shoulder, is characterized by a sudden sharp or paralyzing pain when the shoulder is moved forcibly into a position of maximum external rotation in elevation or is subjected to a direct blow 1. The patient is no longer able to perform a throwing movement with the control and the velocity that he achieved before the injury due to pain and numbness. The “dead arm” is perhaps the most feared malady among throwing athletes 2. Dead arm syndrome has been defined as an inability for the thrower to throw with his preinjury velocity and control because of a combination of pain and subjective unease in the shoulder, is extremely disabling and potentially career-ending to the overhead athlete 3. The dead arm syndrome is seen most commonly in young athletes (21-30 years) or individuals whose arms have been powerful hyperextended in elevation and external rotation of the shoulder 1. For years, physicians have been frustrated by poor results with conventional treatment in this group of athletes. In fact, as recently as the 1970s, pitchers with dead arm syndrome were often referred to psychologists and psychiatrists to discover why they “didn’t want to throw” 3. This attitude received solid support in the orthopedic literature.

A relationship exists between anterior shoulder subluxation and thoracic outlet syndrome that is responsible for the more florid symptoms of dead arm syndrome in some patients 4. This causes a transient stretch to the brachial plexus or transient brachial plexus neuropraxia during a hard throw 5. This relationship was demonstrated in eight of 27 patients (30%) in a consecutive series of Bankart operations for treatment of subluxation. Dead arm syndrome is associated with a disturbance in the kinesiology of the shoulder-joint complex that alters the position of the scapula relative to the rib cage and neurovascular supply to the upper limb.

Dead arm syndrome treatment is directed toward restoration of the stability of the glenohumeral joint so that normal biomechanics can be reestablished. In advanced stages of thoracic outlet syndrome, however, dead arm syndrome may initially require surgical decompression of the nerves and vessels. Careful attention to postural mechanics is essential for rational diagnosis and treatment of dead arm syndrome.

Shoulder anatomy

Your shoulder is a complex joint that is capable of more motion than any other joint in your body. It is made up of three bones: your upper arm bone (humerus), your shoulder blade (scapula), and your collarbone (clavicle).

Your arm is kept in your shoulder socket by your rotator cuff. These muscles and tendons form a covering around the head of your upper arm bone and attach it to your shoulder blade.

There is a lubricating sac called a bursa between the rotator cuff and the bone on top of your shoulder (acromion). The bursa allows the rotator cuff tendons to glide freely when you move your arm.

The shoulder region includes the glenohumeral joint, the acromioclavicular joint, the sternoclavicular joint and the scapulothoracic articulation (Figure 1). The glenohumeral joint capsule consists of a fibrous capsule, ligaments and the glenoid labrum. Because of its lack of bony stability, the glenohumeral joint is the most commonly dislocated major joint in the body. Glenohumeral stability is due to a combination of ligamentous and capsular constraints, surrounding musculature and the glenoid labrum. Static joint stability is provided by the joint surfaces and the capsulolabral complex, and dynamic stability by the rotator cuff muscles and the scapular rotators (trapezius, serratus anterior, rhomboids and levator scapulae).

Scapular stability collectively involves the trapezius, serratus anterior and rhomboid muscles. The levator scapular and upper trapezius muscles support posture; the trapezius and the serratus anterior muscles help rotate the scapula upward, and the trapezius and the rhomboids aid scapular retraction.

Ball and socket. The head of your upper arm bone fits into a rounded socket in your shoulder blade. This socket is called the glenoid. A slippery tissue called articular cartilage covers the surface of the ball and the socket. It creates a smooth, frictionless surface that helps the bones glide easily across each other.

The glenoid is ringed by strong fibrous cartilage called the labrum. The labrum forms a gasket around the socket, adds stability, and cushions the joint.

Shoulder capsule. The joint is surrounded by bands of tissue called ligaments. They form a capsule that holds the joint together. The undersurface of the capsule is lined by a thin membrane called the synovium. It produces synovial fluid that lubricates the shoulder joint.

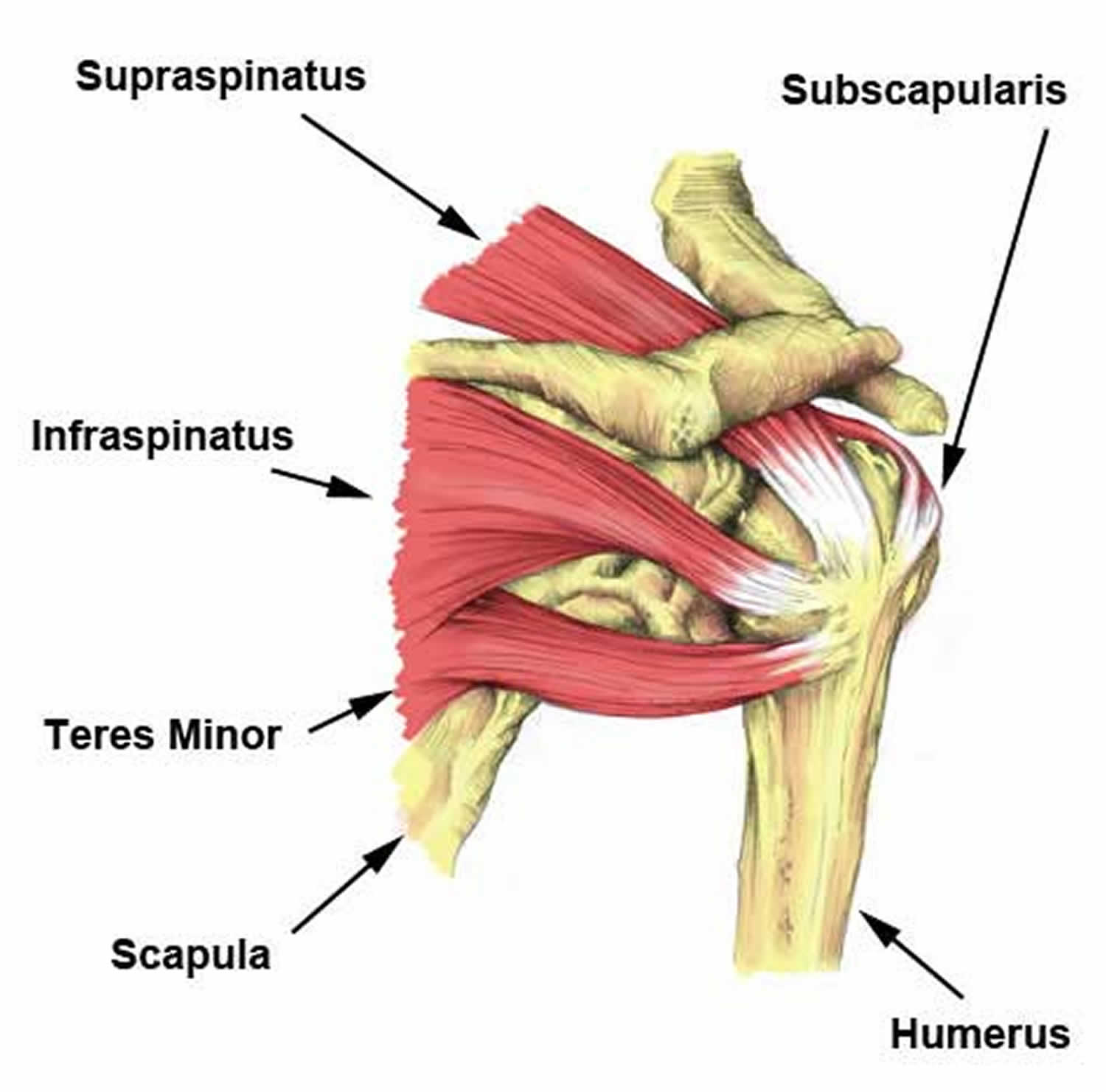

Rotator cuff. The rotator cuff is composed of four muscles: the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis (Figure 2). Four tendons surround the shoulder capsule and help keep your arm bone centered in your shoulder socket. This thick tendon material is called the rotator cuff. The cuff covers the head of the humerus and attaches it to your shoulder blade. The subscapularis facilitates internal rotation, and the infraspinatus and teres minor muscles assist in external rotation. The rotator cuff muscles depress the humeral head against the glenoid. With a poorly functioning (torn) rotator cuff, the humeral head can migrate upward within the joint because of an opposed action of the deltoid muscle.

Bursa. There is a lubricating sac called a bursa between the rotator cuff and the bone on top of your shoulder (acromion). The bursa helps the rotator cuff tendons glide smoothly when you move your arm.

Figure 1. Shoulder anatomy

Figure 2. Rotator cuff muscles and tendons

Dead arm syndrome causes

Dead arm syndrome is a disorder that can have different causes. Mostly it is a problem with the rotator cuff or the labrum. Instability of the shoulder or posterior capsular contracture may be a reason for the development of the dead arm syndrome. In addition, it can also be caused by calcification in the ball and socket joint, bone spurs in the acromion, impingement of the shoulder ligaments, biceps tendonitis, micro-instability, internal impingement and SLAP (superior labral tear from anterior to posterior) lesion 3. A SLAP tear is an injury to the labrum of the shoulder, which is the ring of cartilage that surrounds the socket of the shoulder joint. Psychological factors can also cause this condition. Dead arm syndrome may also occur during throwing, repetitive forceful serving in tennis, or working with the arm in a strained position above shoulder. The symptoms can exacerbate by the loss of the posterior rollback. This leads to anterior translation and results in greater internal impingement posteriorly 6.

Rowe and Zarins 7 defined a dead arm syndrome inpatients with recurrent transient anterior subluxation of the shoulder. They stated that patients with dead arm syndrome experienced sudden pain and weakness with the arm in abduction and external rotation. Overhead athletes who developed dead arm syndrome were unable to throw hard. Burkhart and Parten 3 definition of the dead arm syndrome as a pathologic shoulder condition in which throwers are unable to throw with their preinjury velocity and control is a functional description of the symptom complex described by Rowe and Zarins. Interestingly, part of the mystery and mythology of the dead arm syndrome lies in the fact that throwers often have difficulty in describing the uneasy sensations they feel as they attempt to throw a ball. They usually relate the discomfort to the late cocking phase of the throwing sequence, when the arm begins to accelerate forward. This is the same part of the pitching sequence in which the injury is sustained; pitchers feel a sudden sharp pain in late cocking, when the shoulder is maximally abducted and externally rotated, and then the arm “goes dead” as they try to accelerate it. This consistent history has led the some experts to conclude that this is an acceleration injury 2 rather than a deceleration injury, as previously hypothesized by Andrewset al. 8.

Dr. Frank Jobe et al. 9 described impingement-instability overlap. They postulated that repetitive throwing gradually stretched out the anterior capsuloligamen-tous complex, allowing anterosuperior migration of the humeral head during throwing, thus causing subacromialimpingement symptoms. They reported some successwith open anterior capsulolabral reconstruction, but theirnumbers were small and their results far from ideal (50%returned to pitching in a report of 12 pitchers) 9.

Andrews et al. 8 first observed anterosuperior glenoid labrum tears in throwers, and their treatment was to arthroscopically debride these lesions. They postulated that this labral injury was a deceleration injury that occurred in the follow-through phase of throwing, with the biceps acting as a decelerator of the rapidly extending elbow 8. They theorized that this tensile force in the biceps caused a traction injury to the anterosuperior labrum by virtue of the biceps root attachment to the anterosuperior labrum. Snyder et al. 10 subsequently described SLAP (superior labrum anterior and posterior) lesions in the general population but did not specifically relate them to the overhead athlete. Dr. Christopher Jobe 11 described posterosuperior glenohumeral impingement (“internal impingement”), whereby a portion of the rotator cuff contacts the posterosuperior glenoid and labrum when the arm is in the cocked position of abduction and external rotation. Jobe credited Walch et al. 12 with initially describing this internal impingement, but he applied his observations to throwing athletes and elucidated an expanded spectrum of injury to the rotator cuff, glenoid labrum, and even bone as a result of this internal impingement. He also hypothesized that the internal impingement in throwers might progressively worsen by gradual repetitive stretching of the anterior capsuloligamentous structures. His theory of anterior microinstability aggravating internal impingement was offered as justification for using anterior capsulolabral reconstruction to treat patients with this problem, even though the results of treatment of pitchers by this procedure were unpredictable (50% re-turn to pitching) 9. Interestingly, Christopher Jobe 11 agreed with Walch 12 that the internal impingement thatthey had both described was physiologic and occurred normally in every shoulder that was placed in the cocked position. Therefore, it is difficult to understand how this normal phenomenon could be thesource of such dramatic shoulder dysfunction as one sees with the dead arm syndrome.

Morgan et al. 13 reported on 53 throwing athletes with torsional type II SLAP lesions who underwent arthroscopic repair of the SLAP lesions without additional surgical treatment. These athletes had an 87% return to preinjury levels of throwing. Of the 53 baseball players, 44 were pitchers, of whom 84% returned to their preinjury level of throwing. This is by far the largest group of surgically treated pitchers in the orthopedic literature,and the results, as judged by return to preinjury levels of throwing, are much better than those of the open instability repairs. In view of the vast improvement in results with this approach to the dead arm syndrome, it is a firm belief that the torsional SLAP lesion is the most common culprit in the injured overhead athlete and that this lesion must be strongly considered in evaluating the injured throwing shoulder.

The term SLAP stands for Superior Labrum Anterior and Posterior. In a SLAP injury, the top (superior) part of the labrum is injured. This top area is also where the biceps tendon attaches to the labrum. A SLAP tear occurs both in front (anterior) and back (posterior) of this attachment point. The biceps tendon can be involved in the injury, as well.

Dead arm syndrome symptoms

Dead arm syndrome symptoms are characterized by sudden pain and a complete lack of strength in the upper arm when it is abducted and externally rotated. It is usually associated with a shoulder instability, such as a dislocation or recurrent subluxation of the glenohumeral joint, caused by repeated throwing.

The common symptoms of a SLAP tear are similar to many other shoulder problems. They include:

- A sensation of locking, popping, catching, or grinding

- Pain with movement of the shoulder or with holding the shoulder in specific positions

- Pain with lifting objects, especially overhead

- Decrease in shoulder strength

- A feeling that the shoulder is going to “pop out of joint”

- Decreased range of motion

- Pitchers may notice a decrease in their throw velocity, or the feeling of having a “dead arm” after pitching

Dead arm syndrome diagnosis

Your doctor will talk with you about your symptoms and when they first began. If you can remember a specific injury or activity that caused your shoulder pain, it can help your doctor diagnose your shoulder problem — although many patients may not remember a specific event. Any work activities or sports that aggravate your shoulder are also important to mention, as well as the location of the pain, and what treatment, if any, you have had.

Dead arm syndrome test

Physical examination

During the physicial examination, your doctor will check the range of motion, strength, and stability of your shoulder.

He or she may perform specific tests by placing your arm in different positions to reproduce your symptoms. Your doctor may also examine your neck and head to make sure that your pain is not coming from a “pinched nerve.”

The results of these tests will help your doctor decide if additional testing or imaging of your shoulder is necessary.

Apprehension test

Apprehension test can be carried out when the patient is either in a standing or in a lying position. The shoulder is moved passively into maximum external rotation and in abduction. Then forward pressure is applied to the posterior aspect of the humeral head. The therapist give pressure against the caput humeri to anterior. The test is positive when the patient suddenly becomes apprehensive, complains of pain in the shoulder and has the feeling that the shoulder will come out of the joint considered a positive test. In the absence of a strongly positive apprehension test, one should suspect that the shoulder disability is caused by something other than transient subluxation.

Imaging tests

- X-rays. This imaging test provides clear pictures of dense structures, like bone. The labrum of the shoulder is made of soft tissue so it will not show up on an x-ray. However, your doctor may order x-rays to make sure there are no other problems in your shoulder, such as arthritis or fractures.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. This test can better show soft tissues like the labrum. To make a tear in the labrum show up more clearly on the MRI, a dye may be injected into your shoulder before the scan is taken.

Arthroscopy

According to Burkhart and Parten 3, definitive diagnosis of a SLAP lesion can only be made arthroscopically. Therefore, the indication for SLAP repair is the discovery of a SLAP lesion atdiagnostic arthroscopic surgery. SLAP lesions may be incidentally found when arthroscopy is being done for instability, rotator cuff tear or other categories of shoulder dysfunction. When they are found, they should be repaired. In non-athletes, one might consider fixation by means of a biodegradable tack. However, in athletes, particularly overhead athletes, Burkhart and Parten 3 strongly believe that a suture anchor technique is the only way to effectively neutralize the peel-back forces that must beresisted by the fixation device.

Dead arm syndrome treatment

Dead arm syndrome treatment includes physical therapy similar to that outlined for shoulder instability and labrum injuries. Surgery may be needed to correct the instability, as well as to repair injuries to the glenoid labrum 5. Once the inflammation and pain have resolved, the patient is subjected to a return to throw program. This takes about 4 weeks 1.

Return of full range of motion and flexibility is needed before beginning strengthening exercises. These included resisted internal rotation, external rotation, and abduction of the shoulder to strengthen the muscles of the rotator cuff which stabilize the head of the humerus. This program, which is best carried out for three to four months, can decrease the pain and disability 14. Rehabilitation of athletes with the dead arm syndrome must include the entire kinetic chain 1.

Sometimes, dead arm syndrome evolves into a full clinical picture of the posteosuperior impingement with a development of a SLAP lesion. Then there is need of a surgical treatment 15. SLAP lesions are repaired through arthroscopy, there are different types of SLAP lesions and the type would determine the repair option 16.

SLAP tears treatment

Nonsurgical treatment

In most cases, the initial treatment for a SLAP injury is nonsurgical.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication. Drugs like ibuprofen and naproxen reduce pain and swelling.

- Physical therapy. Specific exercises will restore movement and strengthen your shoulder. Flexibility and range-of-motion exercises will include stretching the shoulder capsule, which is the strong connective tissue that surrounds the joint. Exercises to strengthen the muscles that support your shoulder can relieve pain and prevent further injury. This exercise program can be continued anywhere from 3 to 6 months, and usually involves working with a qualified physical therapist.

Surgical treatment

Your doctor may recommend surgery if your pain does not improve with nonsurgical methods.

- Arthroscopy. The surgical technique most commonly used for treating a SLAP injury is arthroscopy. During arthroscopy, your surgeon inserts a small camera, called an arthroscope, into your shoulder joint. The camera displays pictures on a video monitor, and your surgeon uses these images to guide miniature surgical instruments. Because the arthroscope and surgical instruments are thin, your surgeon can use very small incisions (cuts), rather than the larger incision needed for standard, open surgery.

Treatment options

There are several different types of SLAP tears. Your surgeon will determine how best to treat your SLAP injury once he or she sees it fully during arthroscopic surgery. This may require simply removing the torn part of the labrum, or reattaching the torn part using sutures. Some SLAP injuries do not require repair with sutures; instead, the biceps tendon attachment is released to relieve painful symptoms.

Your surgeon will decide the best treatment option based upon the type of tear you have, as well as your age, activity level, and the presence of any other injuries seen during the surgery.

Complications

Most patients do not experience complications from shoulder arthroscopy. As with any surgery, however, there are some risks. These are usually minor and treatable. Potential problems with arthroscopy include infection, excessive bleeding, blood clots, shoulder stiffness, and damage to blood vessels or nerves.

Your surgeon will discuss the possible complications with you before your operation.

Rehabilitation

At first, your shoulder needs to be protected while the repaired structures heal. To keep your arm from moving, you will most likely use a sling for 2 to 6 weeks after surgery. How long you require a sling depends upon the severity of your injury and the complexity of your surgery.

Once the initial pain and swelling has settled down, your doctor will start you on a physical therapy program that is tailored specifically to you and your injury.

In general, a therapy program focuses first on flexibility. Gentle stretches will improve your range of motion and prevent stiffness in your shoulder. As healing progresses, exercises to strengthen the shoulder muscles and the rotator cuff will gradually be added to your program. This typically occurs 6 to 10 weeks after surgery.

Your doctor will discuss with you when it is safe to return to sports activity. In general, throwing athletes can return to early interval throwing 3 to 4 months after surgery.

Outcomes

The majority of patients report improved shoulder strength and less pain after surgery for a SLAP tear.

Because patients have varied health conditions, complete recovery time is different for everyone.

In cases of complicated injuries and repairs, full recovery may take several months. Although it can be a slow process, following your surgeon’s guidelines and rehabilitation plan is vital to a successful outcome.

References- CR Rowe and B Zarins, Recurrent transient subluxation of the shoulder, J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:863-872.

- Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. Shoulder injuries in overhead athletes: the “dead arm” revisited. Clin Sport Med 2000;19:125–58.

- Dead Arm Syndrome: Torsional SLAP Lesions versus Internal Impingement. Techniques in Shoulder & Elbow Surgery: June 2001 – Volume 2 – Issue 2 – p 74-84 http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.729.9996&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- The relationship between dead arm syndrome and thoracic outlet syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987 Oct;(223):20-31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3652577

- Richard B. Birrer,Bernard A.. Griesemer,Mary B. Cataletto, M.D.Pediatric sports medicine for primary care, 2002, p348

- Donald H. Johnson, M.D, Practical orthopaedic sports medicine & arthroscopy, 2007

- Rowe CR, Zarins B. Recurrent transient subluxation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg[Am] 1981;63:863–72.

- Andrews JR, Carson W Jr, McLeod W. Glenoid labrum tears related to the long head of the biceps. Am J Sports Med 1985;13:337–41.

- Jobe FW, Giangarra CE, Kvitne RS, et al. Anterior capsulolabral reconstruction of the shoulder in athletes in overhead sports. Am J Sports Med 1991;19:428–34.

- Snyder SJ, Karzel RP, Delpizzo W, et al: SLAP lesions of the shoulder. Arthroscopy 1990;6:274–9.

- Jobe CM. Posterior superior glenoid impingement: expanded spectrum. Arthroscopy 1995;11:530–7.

- Walch G, Boileau J, Noel E, et al. Impingement of the deep surface of the supraspinatus tendon on the posterior superior glenoid rim: an arthroscopic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1992;1:238–43.

- Morgan CD, Burkhart SS, Palmeri M, et al. Type II SLAP lesions: three subtypes and their relationships to superior instability and rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy 1998;14: 553–65.

- Ho CY, The effectiveness of manual therapy in the management of musculoskeletal disorders of the shoulder: a systematic review, Man Ther. 2009 Oct;14(5):463-74. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2009.03.008

- Kibler WB. The role of the scapula in athletic shoulder function. Am J Sports Med 1998;26:325-337

- SLAP Tears. https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases–conditions/slap-tears/