Camptodactyly

Camptodactyly is a permanent progressive flexion contracture at the proximal interphalangeal joints with skin shortening on the palmar surface of the finger and palm 1, either unilaterally or bilaterally 2. Most camptodactyly cases are limited to fifth-finger or camptodactyly pinky finger involvement; however, other fingers (sometimes seen in ring and middle fingers) may also be involved 3. The incidence of camptodactyly is approximately 1% in the general population, and involvement is frequently bilateral. Although camptodactyly inheritance is sporadic, an autosomal dominant pattern with variable penetrance and expressivity has been reported. Three types of camptodactyly have been defined: type 1 is notable in the first year of life, type 2 manifests after 10 yrs of age for reasons that remain unclear and type 3 is associated with other congenital anomalies 4.

Camptodactyly types:

- Type I – infant onset

- Type II – adolescent onset, more common in girls than boys

- Type III – associated with other congenital anomalies

Camptodactyly often does not cause functional impairment, meaning that patients seek medical attention for concerns relating to cosmetic appearance or military recruitment 1. Benson et al. 5 stated that while patients who presented early with camptodactyly have an equal sex distribution, late-onset patients are mostly females.

Camptodactyly can be caused by a number of different abnormal structures in your child’s finger:

- Abnormal muscles in the hand.

- Differences in bone shape

- Tight skin

- Contracted tendons and ligaments

Camptodactyly may accompany other anomalies or a number of very rare syndromes. Therefore, physicians should carefully examine patients for other musculoskeletal deformities 4. Other causes of proximal interphalangeal joint flexion, such as Boutonniere deformity, Dupuytren contracture, trigger finger, and an absent extensor mechanism, must be ruled out before confirming the diagnosis. Isolated camptodactyly is not a rare condition; however, it may be overlooked if it is restricted to the fifth fingers and does not influence hand function. Camptodactyly of finger can be mistaken for other rheumatologic disorders, including rheumatoid arthritis and Dupuytren contracture. Clinical and radiological parameters are used to define the extent of the deformity and joint flexibility 6.

The diagnosis of camptodactyly at the onset is of utmost importance because the use of splints and stretching at that time may be useful. Early identification of camptodactyly will also prevent unnecessary diagnostic work-up and patient anxiety. If camptodactyly is left untreated for several years, the position of permanent fixation leads to contracture in the joint 3. Nonoperative and operative management have been proposed to treat camptodactyly, depending on its clinical severity. These diverse techniques range from splinting or stretching exercises to release of tendons, fascial bands, transfer of muscles, and tenotomy 7.

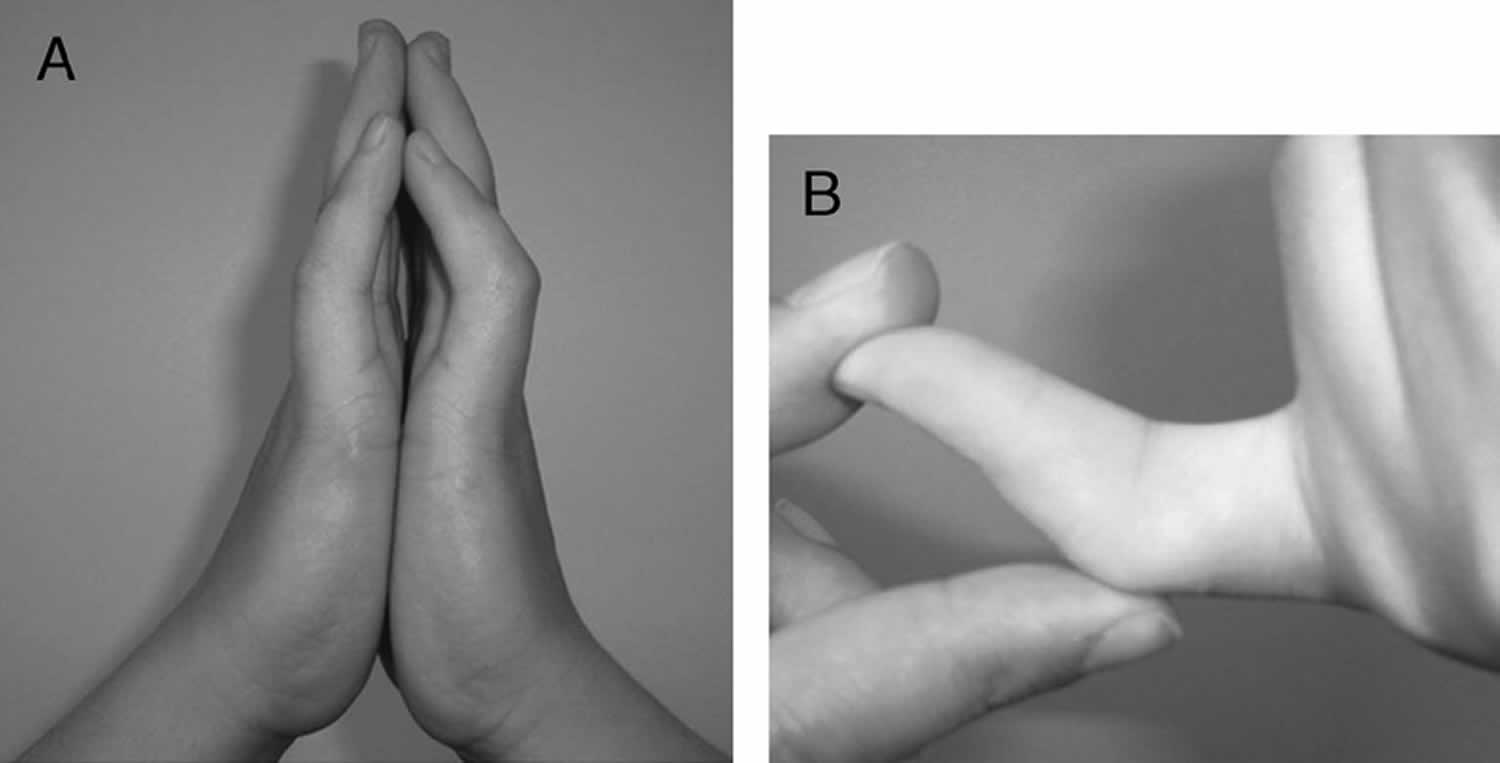

Figure 1. Camptodactyly pinky finger

Footnote: (A) Bilateral flexion deformity of the proximal interphalangeal joints of the fifth finger. (B) The left fifth finger lacks passive extension.

[Source 8 ]Camptodactyly causes

While the origin of camptodactyly remains unknown, it is believed to have a genetic component and may be linked to disruptions in prenatal development. Several causes have been proposed, including abnormal lumbricals; short flexor digitorum superficialis, which is often accompanied by subsequent or associated skin shortening; tight fascial bands; a deficient dorsal central slip extensor mechanism; and changes in the distal interphalangeal joint or metacarpophalangeal joint 9. Camptodactyly can have an early or late onset, and it has been proven to show an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance 10.

Camptodactyly signs and symptoms

The main symptom of camptodactyly is a slightly flexed posture of the middle joint, where the finger cannot completely straighten. Camptodactyly is most common in the little finger, but may affect other fingers as well. Camptodactyly may worsen over time, and may often worsen during growth spurts.

In most cases, camptodactyly does not cause pain or significantly affect the function of the hand. Camptodactyly does not cause swelling, inflammation or warmth to the area.

Camptodactyly diagnosis

Camptodactyly is diagnosed by your child’s doctor after a thorough medical history and careful physical examination. X-rays are also used to confirm the diagnosis.

In addition to a physical exam and X-rays, your child may also undergo:

- Range of motions tests to determine if the condition is affecting movement and dexterity

- Nerve assessment tests to determine if the condition has damaged or compressed any nerves

Accurate diagnosis helps us determine the best course of treatment for your child.

Camptodactyly treatment

The treatment of camptodactyly is controversial 1. Many published studies have emphasized conservative treatment, while others have described surgical procedures. The problem with camptodactyly is that it presents in several forms, which means that there is no single model for effective treatment. Your child’s doctor will probably recommend some form of splinting and occupational hand therapy if your child’s camptodactyly is mild. Surgery may be considered if conservative measures have failed.

Nonsurgical treatment

Most cases of camptodactyly do not require surgical intervention.

If your child has a mild case of camptodactyly — less than a 30-degree bend in their finger that is not affecting hand function — nonoperative treatment will be recommended.

Nonoperative treatment may include:

- Finger and joint stretches to extend range of motion for the affected finger or fingers

- A splint to hold the bent finger in a straight position

Camptodactyly splinting

Camptodactyly splinting is very effective with best results achieved from early intervention.

Treatment protocol:

- Severity and response rate of contracture guides the splinting regime/hours of required splinting. This may vary from 8-20 hours and may be adjusted throughout therapy process.

- Ongoing splinting at night is required to consolidate and maintain the range of extension while growing.

- At times of reduced or slower growth it may be possible to cease splinting until early signs of recurrence indicate a need to resume splinting.

- Exercises/therapeutic play ideas to maintain range of motion and strengthen intrinsic and extrinsic extension are to be prescribed as indicated.

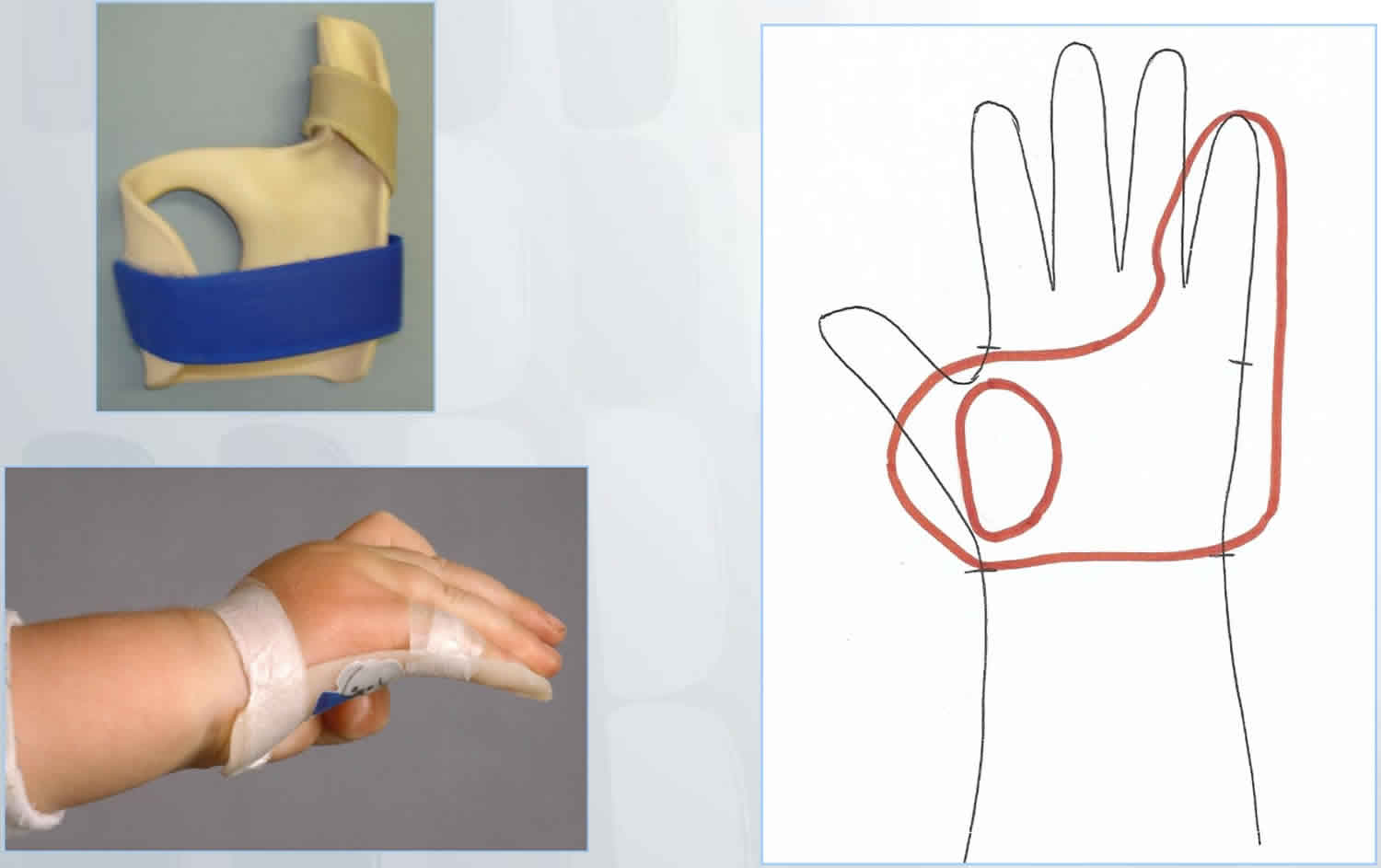

Camptodactyly splint design:

- Hand-based to ensure that the palmar skin is lengthened and the proximal interphalangeal joint is extended while avoiding hyperextension at the metacarpophalangeal joint and distal interphalangeal joint.

- Ensure unaffected fingers, thumb and wrist are not included in the splint and are therefore free to move.

- Secure finger/s with either velcroor paper tape at the distal end of the proximal phalanx.

- Tape prevents the splint from shifting and is more difficult for young children to remove than Velcro is. Adolescents may find Velcro easier to manage independently.

Figure 2. Camptodactyly splint

Camptodactyly surgery

If your child’s finger curvature increases rapidly, or if it progresses to the point where it interferes with hand function, your child’s doctor may recommend surgery. As there is no single cause for camptodactyly, no single operative procedure is recommended for all children. Surgery is most effective if performed while your child is still young and the bones are not fully matured.

Two common procedures are:

- Dividing the tendon that is causing the muscle shortening

- Transferring a tendon and/or muscle to restore balance to the hand

In rare cases, where a child’s camptodactyly is related to abnormal bones or bone structure, doctors may need to perform surgery to repair, remove or fuse a bone to optimize hand function. During this process some range of motion in the joint may be lost. After surgery, your child’s finger, hand or arm may be put in a cast, splint or sling to immobilize it as it heals.

In this study 1, operative management was planned for all cases with >60° of involvement. Further, the type of surgery was decided on the basis of the anatomical defects that were encountered on the operating table. The most commonly affected structure was the flexor digitorum superficialis, which was short and tight in 10 cases (64.29%), followed by skin shortening in two cases (14.29%) and tight flexor digitorum superficialis alone in two cases (14.29%).

Of the patients, seven (50%) underwent flexor digitorum superficialis release alone, three (21.43%) underwent flexor digitorum superficialis release and transfer to the extensors, two (14.29%) underwent flexor digitorum superficialis release and split-thickness skin grafting cover or Z-plasty, one (7.14%) had flexor digitorum superficialis release along with release of fascial bands, and one (7.14%) underwent transfer of an anomalous lumbrical insertion to the lateral band. Static splinting was administered for 2 to 3 weeks in cases of tendon transfer, after which patients were taught to engage in gradual mobilization of the proximal interphalangeal joint for 6 weeks. Night splinting was continued for a prolonged time in all cases.

On the scale (Mayo Clinic) of Siegert et al. 11, Singh et al 1 observed that irrespective of the anatomical structure affected and the surgical option used, postoperative functional integrity remained the same. However, full correction of flexion without ankylosis was not achieved in any patients. In a comparison with peer groups worldwide, Singh et al 1 found that although several procedures have been developed, simple release of the flexor digitorum superficialis, fascia, or skin mostly suffices, with no need to disturb the extensor mechanism. This, in turn, results in postoperative compromise in flexion.

Follow-up care

Follow-up care for camptodactyly will depend on the treatment needed. If your child received nonsurgical treatment, they should be monitored regularly to ensure the condition is not worsening.

If your child had surgery, they will be examined at 2 weeks and 6 weeks post-operatively, then monitored regularly. Your child’s doctor will give you specific information about a recovery program for your child and how soon they can return to daily activities.

Camptodactyly prognosis

The long-term outlook for children with camptodactyly is very good. While most children with the condition can avoid surgery, those who do need surgery generally have good outcomes.

While surgery is usually successful in partially correcting the curvature, your child will likely have some residual deformity. There is a risk for recurrence and need for future surgery.

References- Singh V, Haq A, Priyadarshini P, Kumar P. Camptodactyly: An unsolved area of plastic surgery. Arch Plast Surg. 2018;45(4):363–366. doi:10.5999/aps.2017.00759 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6062706

- Hamilton KL, Netscher DT. Multidigit camptodactyly of the hands and feet: a case study. Hand (N Y) 2013;8:324–9.

- Dautel G: Camptodactylies. Chir Main 2003; 22: 115–24

- Siegert JJ, Cooney WP, Dobyns JH: Management of simple camptodactyly. J Hand Surg Br 1990; 15: 181–9

- Benson LS, Waters PM, Kamil NI, et al. Camptodactyly: classification and results of nonoperative treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 1994;14:814–9.

- Foucher G, Lorea P, Khouri RK, et al. Camptodactyly as a spectrum of congenital deficiencies: a treatment algorithm based on clinical examination. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:1897–905.

- Glicenstein J, Haddad R, Guero S. Surgical treatment of camptodactyly. Ann Chir Main Memb Super. 1995;14:264–71.

- Bilateral Fifth-Finger Camptodactyly. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation: July 2012 – Volume 91 – Issue 7 – p 638 https://journals.lww.com/ajpmr/fulltext/2012/07000/Bilateral_Fifth_Finger_Camptodactyly.13.aspx

- Santosh R, Haobijam N, Barad AK, et al. Absent flexor digitorum profundus (FDP): an unreported component of camptodactyly. J Med Soc. 2014;28:120–2.

- McFarlane RM, Classen DA, Porte AM, et al. The anatomy and treatment of camptodactyly of the small finger. J Hand Surg Am. 1992;17:35–44.

- Siegert JJ, Cooney WP, Dobyns JH. Management of simple camptodactyly. J Hand Surg. 1990;15:181–9.