Esophageal web

Esophageal web also called esophageal ring, refers to an esophageal constriction caused by a a thin membranous tissue protruding into the esophageal lumen, pathohistologically comprises squamous epithelial cells and lamina propria mucosae that can occur anywhere along the length of the esophagus but is typically located in the anterior postcricoid area of the proximal esophagus 1. Esophageal web more commonly occur in the cervical esophagus (cervical esophageal web) near cricopharyngeus muscle than in the thoracic esophagus. Esophageal web typically arises from the anterior wall and never from the posterior wall; esophageal web can also be circumferential 2. Esophageal web or esophageal ring is the most common structural abnormality of the esophagus. Esophageal webs tend to affect middle-aged females. The terminology, pathogenesis, and treatment of esophageal web or esophageal ring remain controversial 3.

There are congenital webs (middle to lower parts) and acquired webs (cervical esophagus) 4. Most esophageal webs are asymptomatic but can cause difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), chest pain, and aspiration 5.

An esophageal web may indicate an esophagus at higher risk of upper esophageal and hypopharyngeal carcinoma.

Esophageal web treatment options include:

- balloon dilatation

- bougienage during endoscopy

For treatment, bougienage and balloon dilatation have generally been used 6. For bougienage, a guidewire is inserted through the stricture and a dilator is also passed under fluoroscopy 7. Alternatively, an endoscope with a small-caliber-tip transparent hood is passed through the web for bougienage 6. In balloon dilatation, a catheter with a balloon is inserted into the stricture under endoscopic guidance, and the balloon is inflated to dilate the stricture 4. Both techniques require from a single to a few sessions in order to increase the diameter between 15 mm and 20 mm. After dilatation by both techniques, the dilated area is carefully inspected to assess transmural esophageal injury.

Esophageal web causes

The cause of esophageal webs and rings is controversial remains controversial and can be classified as congenital or acquired. Several theories have been proposed for the formation of esophageal webs and rings. These include causes related to congenital origin, iron deficiency, developmental abnormality, inflammation, and autoimmunity.

- Congenital theory: Rings and webs may represent a remnant of embryologic development in which the esophagus fails to recanalize completely. In children, fragments of cartilage in esophageal ring-like structures similar to trachea have been described. Fonkalsrud and Anderson reported ciliated pulmonary epithelium and bronchial remnants in resected specimens; however, the fact that most patients with symptoms present when they are older than 40 years suggests that rings and webs alone do not produce any symptoms 8. Publications in pediatric radiology have suggested that Schatzki rings are more common in children than once thought. Most children are asymptomatic, and, thus, they are probably far less detected than indicated. These findings might support the theory that the pathophysiology of the rings contains a congenital factor.

- Iron deficiency: The link between iron deficiency and esophageal webs remains controversial. Evidence for this theory is limited by the uncertainty in the duration of iron deficiency necessary for web formation. Another challenge to this theory is that most esophageal webs are asymptomatic. In rabbits that were iron deficient, histologic examination of esophageal muscle revealed muscle fiber abnormalities. This histologic finding suggests that myasthenic changes in esophageal muscles may lead to dysphagia. In patients with postcricoid webs and Plummer-Vinson syndrome, histologic findings of hyperplasia degeneration of mucosa have been reported and attributed to iron deficiency. Okamura 9 hypothesized that mucosal degeneration can lead to a cascade of decrease in swallowing, restriction of esophageal wall dilation, repetitive tissue injury and healing, and, eventually, permanent esophageal mucosal changes, such as a web. Chisholm and associates 10 observed 72 patients with postcricoid webs for 15 years and found iron deficiency in 90%. However, an epidemiologic study by Elwood et al 11 failed to show a correlation between iron deficiency and cervical esophageal webs. Other nonsupportive studies include the equal likelihood of esophageal webs in patients who are iron deficient and in controls, lack of anemia in most patients with esophageal webs, and resolution of dysphagia but not webs following iron therapy. Further, Chisholm 10 reported only a 10% prevalence of esophageal webs in patients who were iron deficient. Studies are needed to determine if the duration or severity of iron deficient anemia influences web formation with or without dysphagia.

- Developmental theory: Esophageal rings have been postulated to occur during development when a pleat of mucosa is formed by infolding of redundant esophageal mucosa due to shortening of the esophagus. The cause for the repeated plication is unknown.

- Inflammation theory: Inflammatory cells can be found in biopsy specimens of esophageal rings and webs. These inflammatory cells are more common in distal esophageal lesions than in proximal esophageal lesions. The presence of neutrophils suggests an acute inflammatory response to a variety of insults, including gastroesophageal reflux, medications, caustic ingestion, radiation, and trauma. Eosinophil infiltration suggests a cause from gastroesophageal reflux, allergic response (food), and idiopathic eosinophil gastroenteritis. The finding of lymphocytes and plasma cells suggests chronic inflammation.

- Autoimmune theory: Autoimmune diseases have been associated with esophageal webs and include thyroid disease, rheumatoid arthritis, graft versus host disease, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, psoriasis, blistering skin diseases, and pernicious anemia. Patients with Plummer-Vinson syndrome have elevated thyroid cytoplasmic autoimmune antibodies of unknown significance. No other autoimmune antibodies have been associated with esophageal webs. More studies are needed to support this casual association.

Acquired causes for esophageal webs include Plummer-Vinson syndrome, iron deficiency anemia, celiac sprue, inlet patch, graft versus host disease, and skin diseases 3.

Lower esophageal rings

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) has been studied as a cause of lower esophageal rings. Symptomatic esophageal rings typically present when an individual is older than 40 years, suggesting that chronic injury from GERD may be involved in the pathogenesis. Although lower esophageal rings are thinner structures than peptic strictures and have no surrounding inflammation, they may be part of the spectrum of GERD-related injury.

In a small retrospective study using endoscopy and barium radiography, Chen et al 12 demonstrated a progression of normal mucosa or lower esophageal ring to peptic stricture in some patients. In another study using endoscopy or ambulatory pH monitoring, Marshall et al 13 found gastroesophageal reflux in 13 of 20 (65%) consecutive patients with symptomatic lower esophageal rings. Most Schatzki rings are associated with a hiatal hernia, suggesting that GERD may be involved in their pathogenesis.

With regard to esophageal motility, Chen et al 12 found no relationship between lower esophageal rings and esophageal dysmotility or lower esophageal sphincter hypotension. Evidence exists that acid suppression prevents recurrent symptoms in patients with peptic strictures. Similar studies are needed to demonstrate the effects of acid suppression on symptomatic lower esophageal rings. However, a study by Ott and associates 14 using ambulatory pH monitoring found no difference in abnormal distal esophageal acid exposure in patients with hiatal hernia and lower esophageal rings compared to those with hiatal hernia alone.

Patients with evidence of Schatzki rings commonly present with gastric acid symptomatology. It has been speculated that acid suppression may reduce the recurrence of Schatzki rings. Dilation followed by acid suppression treatment reduced the risk of recurrence, even in patients without previous reflux symptoms. Sgouros et al 15 observed 44 consecutive patients who underwent dilation of Schatzki rings. Esophageal manometry and pH studies revealed that 14 had objective evidence of GERD, all of whom were treated with omeprazole. The remaining patients were randomly assigned to omeprazole or placebo. There were no recurrences of Schatzki rings in the group with documented GERD during a mean follow-up of 43 months. Recurrence rates were also significantly lower in the group without objective evidence of GERD who were randomized to omeprazole.

Smith et al 16 evaluated 336 patients with peptic esophageal strictures that were randomized to omeprazole (20 mg daily) or ranitidine (150 mg twice daily) for 1 year after esophageal dilation to 12-18 mm. Subsequent endoscopy and dilation was performed when clinically indicated. The omeprazole-treated patients required significantly fewer repeated dilation sessions (30% vs 46%) and had improved dysphagia scores compared to the ranitidine-treated group.

The ingestion of alkaline or acidic agents can cause caustic injury to the esophagus. Severe injuries have occurred from ingestion of alkaline agents, such as lye, sodium and potassium hydroxides in oven cleaners, washing detergents, Clinitest tablets, cosmetics, soaps, and button batteries. Ingestion of caustic agents can lead to esophageal stricture. Milder injuries have occurred from ingestion of alkaline agents, such as sodium carbonate, ammonium hydroxide, and bleaches (sodium, calcium hypochlorite, hydrogen peroxide). Toilet bowel cleaners (sulfuric, hydrochloric), antirust compounds (hydrochloric, oxalic), battery fluids (sulfuric), and slate cleaners (hydrochloric) can cause acid injuries. Esophageal strictures from caustic injury develop in 15-38% of cases and occur as early as 2 weeks after caustic exposure.

Uncommon causes of lower esophageal rings include pill-induced esophagitis, rare skin disorders, such as epidermolysis bullosa dystrophica, benign mucous membrane pemphigoid, and mediastinal radiation.

Upper esophageal webs

The association between iron deficiency and esophageal webs is controversial. Chisholm and Jacobs supported this association in 2 case series of 72 and 63 patients 10. However, a careful epidemiologic study by Elwood 11 failed to show a correlation between iron deficiency and cervical esophageal webs. Less controversy is found between iron deficiency and dysphagia without webs. Iron deficiency clearly can precede dysphagia. Chisholm 10 and Bredenkamp et al 17 noted resolution of dysphagia but not webs after iron supplementation.

Plummer-Vinson syndrome or Paterson-Brown-Kelly syndrome is characterized by postcricoid or upper esophageal webs eccentrically attached to the anterior wall of the esophagus and iron deficiency anemia. Other associated features of Plummer-Vinson syndrome are koilonychia, cheilosis, and glossitis. Webs are believed to arise in iron deficiency states. Pharyngeal and cervical esophageal cancers have been associated with Plummer-Vinson syndrome. Periodic screening for esophageal cancer in patients with Plummer-Vinson syndrome is recommended because of its malignant potential.

Celiac disease or gluten-sensitive enteropathy is characterized by small intestinal malabsorption. Histologic examination reveals a flat mucosal surface with complete absence of normal intestinal villi. Because iron is absorbed predominantly in the proximal small intestine, iron absorption is impaired in celiac disease. Dickey and McConnell 18 described 2 patients with Plummer-Vinson syndrome and chronic iron deficiency anemia who were found to have celiac disease by histology. Dickey and McConnell 18 hypothesized that iron deficiency from celiac disease is the primary cause of upper esophageal webs and Plummer-Vinson syndrome.

Heterotropic gastric mucosa can occur throughout the esophagus, and it is termed an inlet patch if it occurs in the proximal esophagus. The typical location of an inlet patch is usually right below the cricopharyngeal muscle at approximately 20-25 cm from the incisors. Inlet patch has been observed in 2.8% and 3.5% of consecutive endoscopies. On biopsy, corpus-fundic or antral-type mucosa is observed, sometimes containing parietal cells capable of acid secretion. Inlet patches are usually incidental findings, and most cases are believed to be clinically insignificant. Rarely, an esophageal ring and web can be found at the distal margin of the inlet patch, presumably from exposure to acid secretion.

Upper esophageal webs have been reported in patients with chronic graft versus host disease after bone marrow transplantation. The mechanism is believed to be the accretion of desquamated esophageal epithelium. Caution is advised when performing endoscopy in patients with esophageal webs and graft versus host disease because of an increased risk of perforation.

Several skin diseases have been reported in association with esophageal webs, including mucous membrane pemphigoid (cicatricial pemphigoid), epidermolysis bullosa, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, and psoriasis. An autoimmune process is believed to be the cause of these associations.

Other esophageal disorders have been reported to be associated with esophageal webs, including Zenker diverticulum, as shown below, and esophageal duplication cyst. The pathogenesis for these associations is unknown.

Esophageal web symptoms

Patients with esophageal web are usually asymptomatic and the finding may be incidental and unimportant. However, if the stricture is severe symptoms include difficulty swallowing (dysphagia) and regurgitation of food.

Esophageal web complications

Intermittent dysphagia to solid food is the most common complication.

Food impaction, particularly of meat products, is common in patients with lower esophageal rings. Signs of esophageal obstruction are dysphagia and an inability to swallow secretion. This is a medical emergency, and prompt endoscopy with removal of the obstructed food bolus is warranted. Intravenous glucagon is not an effective therapy. To prevent aspiration, barium studies are contraindicated in patients with suspected food impaction.

Spontaneous esophageal perforations have been reported for both esophageal webs and rings. The subgroup of patients who may be at risk of this rare complication is unclear.

Esophageal rings may progress to a stricture, possibly due to underlying GERD. Aggressive GERD management may be needed.

For unknown reasons, patients with Plummer-Vinson syndrome are at a higher risk of esophageal carcinoma.

Celiac disease may present as Plummer-Vinson syndrome. Test for antigliadin and antiendomysial antibodies. Duodenal biopsy is recommended in patients with Plummer-Vinson syndrome.

Esophageal web diagnosis

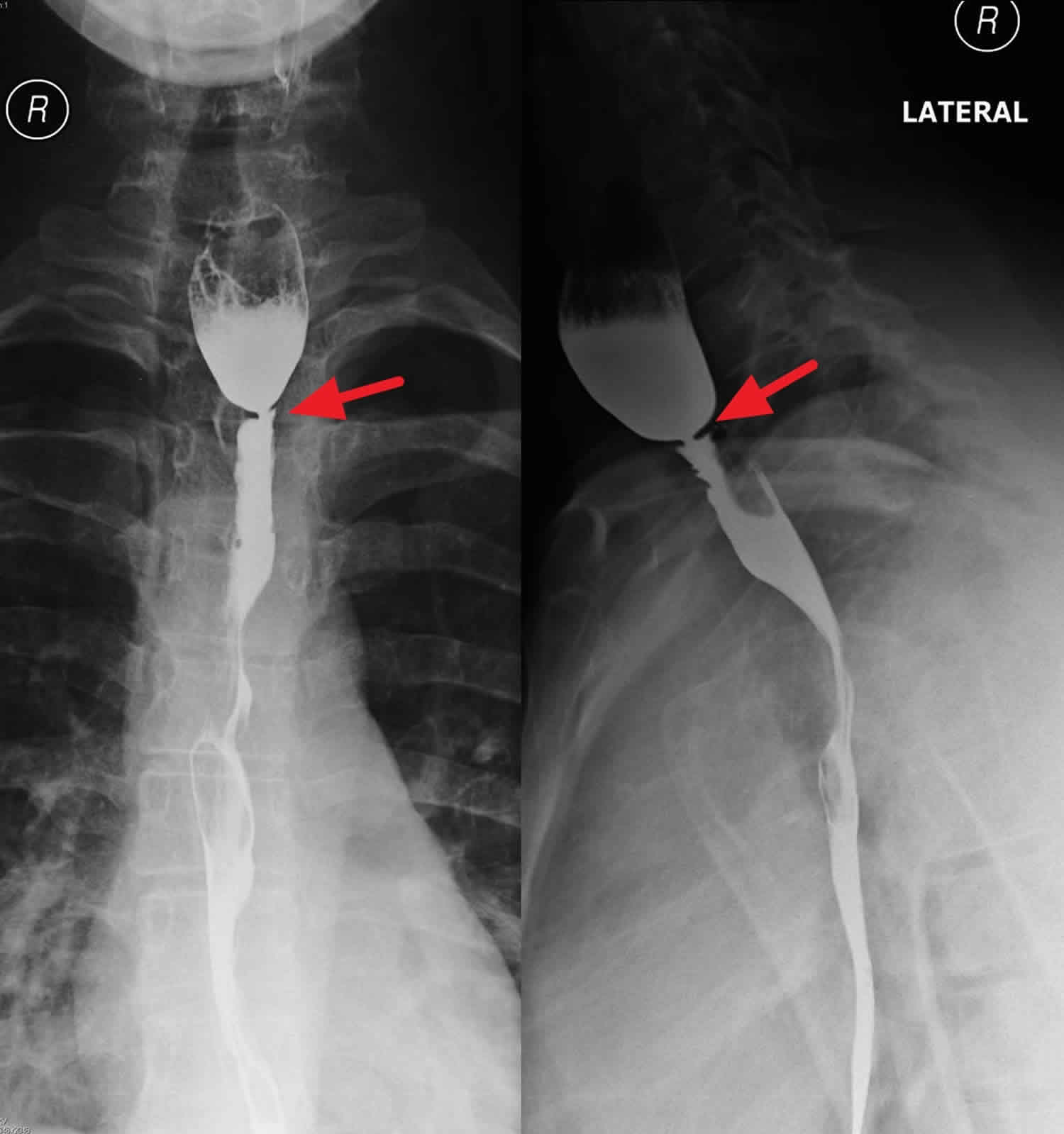

Barium swallow

Barium swallow is the diagnostic test of choice and should be the initial test in patients with dysphagia. Barium swallow allows detection of intraluminal obstruction. In addition to detecting esophageal rings and webs, it is useful in excluding other diagnoses, including peptic strictures, pill-induced esophagitis and/or strictures, mucosal tumors, intramural tumors (primarily leiomyomas), and extraesophageal compression. Infections related to candidiasis, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and idiopathic ulcers sometimes may be suspected following barium studies.

Barium studies are relatively safe, with low radiation exposure, and relatively inexpensive. Most clinicians believe that the barium swallow is more sensitive than endoscopy in detecting rings and webs. A presbyesophagus (tortuous) or a hypermobile esophagus can prevent detection of a small ring or web by endoscopy. In addition, a barium swallow provides a “roadmap” for the endoscopist.

Reflux of barium provides additional information on the competency of the lower esophageal sphincter and the presence of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Finally, the administration of a barium pill at the end of the examination is recommended because the finding of obstruction to a 13-mm pill indicates a high-grade obstruction and the need for esophageal dilation.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy or upper endoscopy is diagnostic and enables therapeutic intervention in patients with symptomatic esophageal rings and webs.

It is probably less sensitive than barium radiography when diagnosing esophageal rings and webs. In fact, the physician occasionally can miss the diagnosis with endoscopy because of the fragility of esophageal webs, hypermotility of the esophagus, the presence of excessive fluid and secretion in the esophagus, presbyesophagus (tortuosity), or very small rings and webs.

Endoscopy allows biopsy of lesions, such as strictures, polyps, or masses, when any question of malignancy exists.

Routine biopsy of rings and webs is not necessary. Histologic findings of esophageal webs are usually normal squamous epithelia with occasional chronic inflammatory cells in the subepithelial tissue.

Lab tests

To establish a diagnosis of celiac sprue, iron deficiency anemia, and Plummer-Vinson syndrome, the following tests are necessary:

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Iron panel

- Ferritin

- Antigliadin antibodies

- Antiendomysial antibodies

Esophageal web treatment

Patients with recurrent symptoms from esophageal rings and webs require repeat esophageal dilation. Repeat esophageal dilation is safe and can relieve symptoms in the long term.

Histamine type 2 (H2)-receptor antagonists, including cimetidine, famotidine, and ranitidine, may be used for mild-to-moderate GERD symptoms.

For severe GERD symptoms, proton pump inhibitors (eg, omeprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole, pantoprazole) are recommended.

Esophageal dilation

Two types of mechanical bougies are used for esophageal dilation, Savary dilator and Maloney (mercury filled) dilator. Both types of bougies are graded in millimeters (mm) and French (1 F = 3 mm). Both types of dilators are equally effective and safe. Perform an initial endoscopy prior to esophageal dilation to confirm the diagnosis when using Maloney dilators. With Savary dilators, an endoscopy is a part of each dilation procedure.

The goal of using mechanical bougies is to disrupt the rings rather than stretching them. In most cases, passage of one large bougie is adequate to disrupt the ring. Despite a lack of conclusive evidence, passing a single large bougie is believed to be more effective than serial progressive dilation of esophageal rings.

Fluoroscopic visualization rarely is needed for either procedure, but it is recommended if the lumen distal ring cannot be visualized.

A persistent ring after esophageal dilation as shown in postdilation barium study does not predict failure of therapy. In fact, in a prospective study by Eckardt et al, 33 consecutive patients with symptomatic esophageal rings experienced relief of their dysphagia after passage of a single Maloney bougie (46-58F), regardless of ring rupture 19. However, repeat dilation is safe and effective.

Unlike the lower esophageal rings, patients with multiple esophageal rings follow a set of different therapeutic rules for esophageal dilation. This recommendation is based on the author’s cumulative experience with this rare condition. The esophageal lumen in patients with multiple esophageal rings is typically much narrower than in patients with lower esophageal rings. Medical therapy alone is usually unsuccessful. The treatment of choice is mechanical dilation. Unlike lower esophageal rings, multiple esophageal rings are tighter, and dilation should be performed very slowly using the smallest size dilator that encounters moderate resistance on initial passage into the esophageal lumen. Initially, only one dilator should be used, with serial dilations reserved for later sessions. Starting with a 20-30F dilator is not uncommon. Transient chest pain from mucosal tear is common after dilation in this population.

Patients with multiple rings may be presenting with eosinophilic esophagitis. Dilation in these patients should be performed with care, as deep mucosal tears and esophageal perforations may occur.

For esophageal rings refractory to esophageal dilation, therapeutic success using neodymium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Nd:YAG) laser therapy has been reported. In a study of 14 patients by Hubert et al 20, Nd:YAG laser incision of lower esophageal rings provided good symptomatic relief.

Like distal esophageal rings, most esophageal webs are asymptomatic and do not require treatment. Mild symptoms often can be treated with diet modification and lifestyle changes. If these conservative measures are unsuccessful, esophageal dilation with mechanical bougie is the next step in treatment. Esophageal dilation with endoscope, bougie, and an esophageal balloon is effective in disrupting esophageal webs, resulting in long-term relief.

Like esophageal rings, postdilation barium study may reveal a persistent esophageal web despite symptom relief. Successful treatment of an esophageal web using Nd:YAG laser has been reported, but this treatment rarely is required. In patients with associated disorders, such as iron deficiency, inflammatory diseases, or chronic graft versus host disease, treating the underlying disorders is warranted.

Newer technology in endoscopic dilation has been studied by Jones et al 21 in a group of 26 patients who presented with dysphagia, as follows:

- The InScope Optical Dilator that allows actual visualization during dilation was used on these patients. Seventeen patients had evidence of peptic stricture, and 9 with Schatzki ring were dilated. Eighteen of these 26 patients reported either significant or complete resolution of the dysphagia at week 3 postdilation.

- The dilations were performed by 2 operators that related the experience similar to the use of bougies with respect to intubation and tactile response. The significant benefit reported was increased visualization during dilation.

- The authors concluded that larger scale trials should be undertaken to validate the theory that direct visualization has an added benefit in esophageal dilation. Patients with eosinophilic esophagitis may benefit the most by this method as dilation of multiple rings may be aborted if excessive tear is seen.

Using the Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative database, based in Portland, Oregon, Olson et al 22 reviewed 7287 patients with strictures and 4993 patients with rings, all with distal lesions, who were compared to 124,120 control subjects, to evaluate the demographic characteristics of patients with symptomatic strictures and rings, to describe the indications and types of therapeutic dilations, and to determine the rate of repeat dilation within 1 year of the initial dilation.

- Strictures showed predominance in males, and rings showed predominance for women, both affecting elderly white patients more than other demographic groups.

- Rings were more often dilated with bougies, and strictures were more likely to require repeated dilation. Repeat dilation for strictures and rings at 1 year was 13% and 4%, respectively. The mean interval length between repeat dilations was 82 days for strictures and 184 days for rings. Dysphagia and reflux symptoms represent the most common indications for esophagogastroduodenoscopy in patients who ultimately receive dilation.

- The study limitation, as acknowledged by the authors, was that there was no way to track those patients who switched gastrointestinal specialists and were now being followed by providers who do not participate in the Clinical Outcomes Research Initiative database.

Esophageal web diet

Patients with mild symptoms from esophageal rings or webs should modify their diet and eating habits.

Soft food, such as pasta, vegetables, and carbohydrates, is less likely than meat to become lodged in the esophagus.

Advise patients to eat slowly, chew thoroughly, and cut large chunks of food into smaller pieces.

Modification of physical activities is not necessary.

Surgery

Esophageal rings and webs rarely need surgical therapy.

Endoscopic sphincterotomy

Endoscopic electrocautery incision using a papillotome catheter was reported to be successful in alleviating symptoms associated with refractory lower esophageal rings in 2 studies involving 7 and 17 patients.

In the first study, 7 patients were observed for as long as 36 months with only 1 patient requiring a second treatment at 6 months and 1 patient developing chest pain after treatment. The patient continued to have persistent dysphagia from the ring but no new symptoms, unlike the patient who developed new-onset chest pain, which is likely a complication from the treatment.

In the second study, 17 patients had a mean follow-up care of 14 months, with 3 patients requiring a second treatment and 1 patient having bleeding.

Esophageal web prognosis

The prognosis in patients with mild symptoms is excellent, because most respond to dietary modifications and change in eating habits.

Patients with refractory dysphagia usually respond to mechanical esophageal dilation.

Patients with recurrent dysphagia after dilation usually respond to repeat dilation. Surgery rarely is needed.

Morbidity and mortality

Most patients with esophageal rings and webs are asymptomatic. Schatzki reported a direct correlation between the luminal diameter of an esophageal ring and patients’ symptoms. Almost all patients with an esophageal lumen less than 13 mm have dysphagia. Patients with esophageal lumen from 13 to -20 mm may or may not have dysphagia, and if the luminal diameter is greater than 20 mm, dysphagia is rare. Spontaneous perforation of the esophagus is also rare, but it has been reported. No reports on mortality exist.

References- Ohtaka M, Kobayashi S, Yoshida T, et al. Use of Sato’s curved laryngoscope and an insulated-tip knife for endoscopic incisional therapy of esophageal web. Dig Endosc. 2015;27(4):522–526. doi:10.1111/den.12334 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4409093

- Eisenberg RL. Gastrointestinal radiology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. (2003) ISBN:0781737060.

- Esophageal Webs and Rings. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/186561-overview

- Dinler G, Tander B, Kalayci AG, Rizalar R. Plummer-Vinson syndrome in a 15-year-old boy. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2009;51:384–386.

- Seo MH, Chun HJ, Jeen YT, et al. Esophageal web resolved by endoscopic incision in a patient with Plummer-Vinson syndrome. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2011;74:1142–1143.

- Itaba S, Nakamura K, Akiho H, Takayanagi R. Endoscopic bougienage for a recurrent esophageal web using a small-caliber-tip transparent hood. Endoscopy. 2008;40:E198

- Enomoto M, Kohmoto M, Arafa UA, et al. Plummer-Vinson syndrome successfully treated by endoscopic dilatation. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2007;22:2348–2351.

- Anderson LS, Shackelford GD, Mancilla-Jimenez R, et al. Cartilaginous esophageal ring: a cause of esophageal stenosis in infants and children. Radiology. 1973 Sep. 108(3):665-6.

- Okamura H, Tsutsumi S, Inaki S, et al. Esophageal web in Plummer-Vinson syndrome. Laryngoscope. 1988 Sep. 98(9):994-8.

- Chisholm M, Ardran GM, Callender ST, et al. Iron deficiency and autoimmunity in post-cricoid webs. Q J Med. 1971 Jul. 40(159):421-33.

- Elwood PC, Jacobs A, Pitman RG, Entwistle CC. Epidemiology of the Paterson-Kelly syndrome. Lancet. 1964 Oct 03. 2(7362):716-20.

- Chen MY, Ott DJ, Donati DL, et al. Correlation of lower esophageal mucosal ring and lower esophageal sphincter pressure. Dig Dis Sci. 1994 Apr. 39(4):766-9.

- Marshall JB, Kretschmar JM, Diaz-Arias AA. Gastroesophageal reflux as a pathogenic factor in the development of symptomatic lower esophageal rings. Arch Intern Med. 1990 Aug. 150(8):1669-72.

- Ott DJ, Ledbetter MS, Chen MY, et al. Correlation of lower esophageal mucosal ring and 24-h pH monitoring of the esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996 Jan. 91(1):61-4.

- Sgouros SN, Vlachogiannakos J, Karamanolis G, et al. Long-term acid suppressive therapy may prevent the relapse of lower esophageal (Schatzki’s) rings: a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005 Sep. 100(9):1929-34.

- Smith PM, Kerr GD, Cockel R, et al. A comparison of omeprazole and ranitidine in the prevention of recurrence of benign esophageal stricture. Restore Investigator Group. Gastroenterology. 1994 Nov. 107(5):1312-8.

- Bredenkamp JK, Castro DJ, Mickel RA. Importance of iron repletion in the management of Plummer-Vinson syndrome. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1990 Jan. 99(1):51-4.

- Dickey W, McConnell B. Celiac disease presenting as the Paterson-Brown Kelly (Plummer-Vinson) syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999 Feb. 94(2):527-9.

- Eckardt VF, Kanzler G, Willems D. Single dilation of symptomatic Schatzki rings. A prospective evaluation of its effectiveness. Dig Dis Sci. 1992 Apr. 37(4):577-82.

- Hubert G, Patrice T, Foultier MT, et al. [Dysphagia and Schatzki ring: treatment using the Nd-YAG laser in 14 patients]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1990. 14(2):186-7.

- Jones MP, Bratten JR, McClave SA. The Optical Dilator: a clear, over-the-scope bougie with sequential dilating segments. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006 May. 63(6):840-5.

- Olson JS, Lieberman DA, Sonnenberg A. Practice patterns in the management of patients with esophageal strictures and rings. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007 Oct. 66(4):670-5; quiz 767, 770.