Exercise prescription

Exercise prescription commonly refers to the specific plan of fitness-related activities that are designed for a specified purpose, which is often developed by a fitness or rehabilitation specialist for the client or patient. Due to the specific and unique needs and interests of the client/patient, the goal of exercise prescription should be successful integration of exercise principles and behavioral techniques that motivates the participant to be compliant, thus achieving their goals 1.

The World Health Organization (WHO) describes exercise as ‘a subcategory of physical activity that is planned, structured, repetitive, and purposeful in the sense that the improvement or maintenance of one or more components of physical fitness is the objective’. Hence, increasing a patient’s physical activity level may include exercise as well as other activities, which involve bodily movement, in playing, active transport, (walking or cycling for example), house chores, and recreational activities. Doctors are also renowned for becoming obsessed with patient weight reduction and measuring body mass index (BMI) rather than increasing physical activity levels per se.

The ideal exercise regimen should consist of periods of warming up, endurance exercise, flexibility exercise, resistance training, and cooling down. The ‘FITT’ principle is a mnemonic commonly used among fitness trainers standing for frequency, intensity, time and type of exercise. By using the FITT principle exercise can be tailored for each individual patient to suit his or her lifestyle and health requirements. It is important to consider that the more intense an exercise is, the greater its effects usually are on fitness, but not necessarily in terms of health benefits. Perhaps the most crucial part of exercise prescription is adequate patient follow-up. Patient compliance is drastically improved when they have been set goals to achieve, and their progress is quantified.

Adding exercise to your routine can positively affect your life. Regular exercise has been proven to help reduce the risk of chronic illnesses such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes and stroke.

Research shows that physical activity can also boost self-esteem, energy, mood and sleep quality.

Exercise can:

- Reduce your risk of heart disease, high blood pressure, osteoporosis, diabetes, and obesity.

- Keep joints, tendons, and ligaments flexible, which makes it easier to move around and decreases your chance of falling.

- Reduce some of the effects of aging, especially the discomfort of osteoarthritis.

- Contribute to mental well-being and help treat depression.

- Help relieve stress and anxiety.

- Increase energy and endurance.

- Improve sleep.

- Help maintain a normal weight by increasing your metabolism (the rate you burn calories).

Two important conclusions from the expert committee, the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the U.S. Surgeon General, the American Heart Association (AHA) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) that have influenced the development of the recommendations appearing in the Guidelines for exercise are the following:

- Important health benefits can be obtained by performing a moderate amount of physical activity on most, if not all, days of the week.

- Additional health benefits result from greater amounts of physical activity. Individuals who maintain a regular program of physical activity that is longer in duration and/or of more vigorous intensity are likely to derive greater benefit than those who engage in lesser amounts.

Exercise prescription is considered to be like any other prescription, with a type, dose, frequency, duration and therapeutic goal 2.

Components of exercise prescription:

- An exercise prescription generally includes the following specific recommendations:

- Type of exercise or activity (eg, walking, swimming, cycling)

- Specific workloads (eg, watts, walking speed)

- Duration and frequency of the activity or exercise session

- Intensity guidelines – Target heart rate range and estimated rate of perceived exertion

- Precautions regarding certain orthopedic (or other) concerns or related comments

Guidelines for physical activity

The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and the American Heart Association (AHA) Primary Physical Activity Recommendations 3

- All healthy adults aged 18–65 year should participate in moderate intensity, aerobic physical activity for a minimum of 30 minutes on 5 days/week or vigorous intensity, aerobic activity for a minimum of 20 minutes on 3 days/week.

- Combinations of moderate and vigorous intensity exercise can be performed to meet this recommendation.

- Moderate intensity, aerobic activity can be accumulated to total the 30 minutes minimum by performing bouts each lasting 10 minutes

- Every adult should perform activities that maintain or increase muscular strength and endurance for a minimum of 2 days/week

- Because of the dose-response relationship between physical activity and health, individuals who wish to further improve their fitness, reduce their risk for chronic diseases and disabilities, and/or prevent unhealthy weight gain may benefit by exceeding the minimum recommended amounts of physical activity.

Adults aged 18–65 years should aim for 150 minutes of moderate intensity activity in bouts of 10 minutes or more (that is, 30 minutes at least 5 days a week) 4. Comparable benefits can be achieved through 75 minutes of vigorous intensity activity spread across the week and at least 2 days of the week activity should be aimed at improving muscle strength. Although the guidelines for people over 65 years are similar, older adults are encouraged to include activities that improve balance and coordination, especially if at risk of falls. Similar guidance can also be found for children, including infants 5. Patients can obtain this ‘daily dose’ by addressing their sedentary lifestyle, for example, taking the stairs instead of a lift, and walking to work.

Exercise prescription guidelines

Physical activity guidelines for children under 5 years

Being physically active every day is important for the healthy growth and development of babies, toddlers and preschoolers. For this age group, activity of any intensity should be encouraged, including light activity and more energetic physical activity.

Physical activity ideas for children under 5

All movement counts. The more the better.

- tummy time

- playing with blocks and other objects

- messy play

- jumping

- walking

- dancing

- swimming

- playground activities

- climbing

- skip

- active play, like hide and seek

- throwing and catching

- scooting

- riding a bike

- outdoor activities

- skipping

Babies (under 1 year)

Babies should be encouraged to be active throughout the day, every day in a variety of ways, including crawling.

If they’re not yet crawling, encourage them to be physically active by reaching and grasping, pulling and pushing, moving their head, body and limbs during daily routines, and during supervised floor play.

Try to include at least 30 minutes of tummy time spread throughout the day when they’re awake.

Once babies can move around, encourage them to be as active as possible in a safe and supervised play environment.

Toddlers (aged 1 to 2)

Toddlers should be physically active every day for at least 180 minutes (3 hours). The more the better. This should be spread throughout the day, including playing outdoors.

The 180 minutes can include light activity such as standing up, moving around, rolling and playing, as well as more energetic activity like skipping, hopping, running and jumping.

Active play, such as using a climbing frame, riding a bike, playing in water, chasing games and ball games, is the best way for this age group to get moving.

Pre-schoolers (aged 3 to 4)

Pre-schoolers should spend at least 180 minutes (3 hours) a day doing a variety of physical activities spread throughout the day, including active and outdoor play. The more the better.

The 180 minutes should include at least 60 minutes of moderate-to-vigorous intensity physical activity.

Children under 5 should not be inactive for long periods, except when they’re asleep. Watching TV, traveling by car, bus or train, or being strapped into a buggy for long periods are not good for a child’s health and development.

All children under 5 who are overweight can improve their health by meeting the activity guidelines, even if their weight does not change. To achieve and maintain a healthy weight, they may need to do additional activity and make dietary changes.

Physical activity guidelines for children aged 5 to 18

Children and young people need to do 2 types of physical activity each week:

- aerobic exercise

- exercises to strengthen their muscles and bones

Children and young people aged 5 to 18 should:

- aim for an average of at least 60 minutes of moderate intensity physical activity a day across the week

- take part in a variety of types and intensities of physical activity across the week to develop movement skills, muscles and bones

- reduce the time spent sitting or lying down and break up long periods of not moving with some activity. Aim to spread activity throughout the day. All activities should make you breathe faster and feel warmer

Moderate activity

Moderate intensity activities will raise your heart rate, and make you breathe faster and feel warmer.

One way to tell if you’re working at a moderate intensity level is if you can still talk, but not sing.

Examples of moderate intensity activities:

- walking to school

- playground activities

- riding a scooter

- skateboarding

- rollerblading

- walking the dog

- cycling on level ground or ground with few hills

Activities that strengthen muscles and bones

Examples for children include:

- walking

- running

- games such as tug of war

- skipping with a rope

- swinging on playground equipment bars

- gymnastics

- climbing

- sit-ups, press-ups and other similar exercises

- basketball

- dance

- football

- rugby

- tennis

Examples for young people include:

- gymnastics

- rock climbing

- football

- basketball

- tennis

- dance

- resistance exercises with exercise bands, weight machines or handheld weights

- aerobics

- running

- netball

- hockey

- badminton

- skipping with a rope

- martial arts

- sit-ups, press-ups and other similar exercises

Physical activity guidelines for adults aged 19 to 65

Adults should do some type of physical activity every day. Any type of activity is good for you. The more you do the better 5

Adults should:

- aim to be physically active every day. Any activity is better than none, and more is better still

- do strengthening activities that work all the major muscles (legs, hips, back, abdomen, chest, shoulders and arms) on at least 2 days a week

- do at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity activity a week or 75 minutes of vigorous intensity activity a week

- reduce time spent sitting or lying down and break up long periods of not moving with some activity.

You can also achieve your weekly activity target with:

- several short sessions of very vigorous intensity activity

- a mix of moderate, vigorous and very vigorous intensity activity

You can do your weekly target of physical activity on a single day or over 2 or more days. Whatever suits you.

These guidelines are also suitable for:

- disabled adults

- pregnant women and new mothers

Make sure the type and intensity of your activity is appropriate for your level of fitness. Vigorous activity is not recommended for previously inactive women.

All of these routines count towards the recommended guidelines for weekly physical activity.

Moderate aerobic activity

Moderate activity will raise your heart rate, and make you breathe faster and feel warmer. One way to tell if you’re working at a moderate intensity level is if you can still talk, but not sing.

For moderate-intensity physical activity, your target heart rate should be between 64% and 76% of your maximum heart rate 6, 7. You can estimate your maximum heart rate based on your age. To estimate your maximum age-related heart rate, subtract your age from 220. For example, for a 50-year-old person, the estimated maximum age-related heart rate would be calculated as 220 – 50 years = 170 beats per minute (bpm). The 64% and 76% levels would be:

- 64% level: 170 x 0.64 = 109 bpm, and

- 76% level: 170 x 0.76 = 129 bpm

This shows that moderate-intensity physical activity for a 50-year-old person will require that the heart rate remains between 109 and 129 bpm during physical activity.

Most moderate activities can become vigorous if you increase your effort.

Examples of moderate intensity activities:

- brisk walking

- water aerobics

- riding a bike

- dancing

- doubles tennis

- pushing a lawn mower

- hiking

- rollerblading

Vigorous activity

Vigorous intensity activity makes you breathe hard and fast. If you’re working at this level, you will not be able to say more than a few words without pausing for breath.

For vigorous-intensity physical activity, your target heart rate should be between 77% and 93% of your maximum heart rate 6, 7. You can estimate your maximum heart rate based on your age. To estimate your maximum age-related heart rate, subtract your age from 220. For example, for a 35-year-old person, the estimated maximum age-related heart rate would be calculated as 220 – 35 years = 185 beats per minute (bpm). The 77% and 93% levels would be:

- 77% level: 185 x 0.77 = 142 bpm, and

- 93% level: 185 x 0.93 = 172 bpm

This shows that vigorous-intensity physical activity for a 35-year-old person will require that the heart rate remains between 142 and 172 bpm during physical activity.

In general, 75 minutes of vigorous intensity activity can give similar health benefits to 150 minutes of moderate intensity activity.

Examples of vigorous activities:

- jogging or running

- swimming fast

- riding a bike fast or on hills

- walking up the stairs

- sports, like football, rugby, netball and hockey

- skipping rope

- aerobics

- gymnastics

- martial arts

Activities that strengthen muscles

To get health benefits from strength exercises, you should do them to the point where you need a short rest before repeating the activity.

There are many ways you can strengthen your muscles, whether you’re at home or in a gym.

Examples of muscle-strengthening activities:

- carrying heavy shopping bags

- yoga

- pilates

- tai chi

- lifting weights

- working with resistance bands

- doing exercises that use your own body weight, such as push-ups and sit-ups

- heavy gardening, such as digging and shoveling

- wheeling a wheelchair

- lifting and carrying children

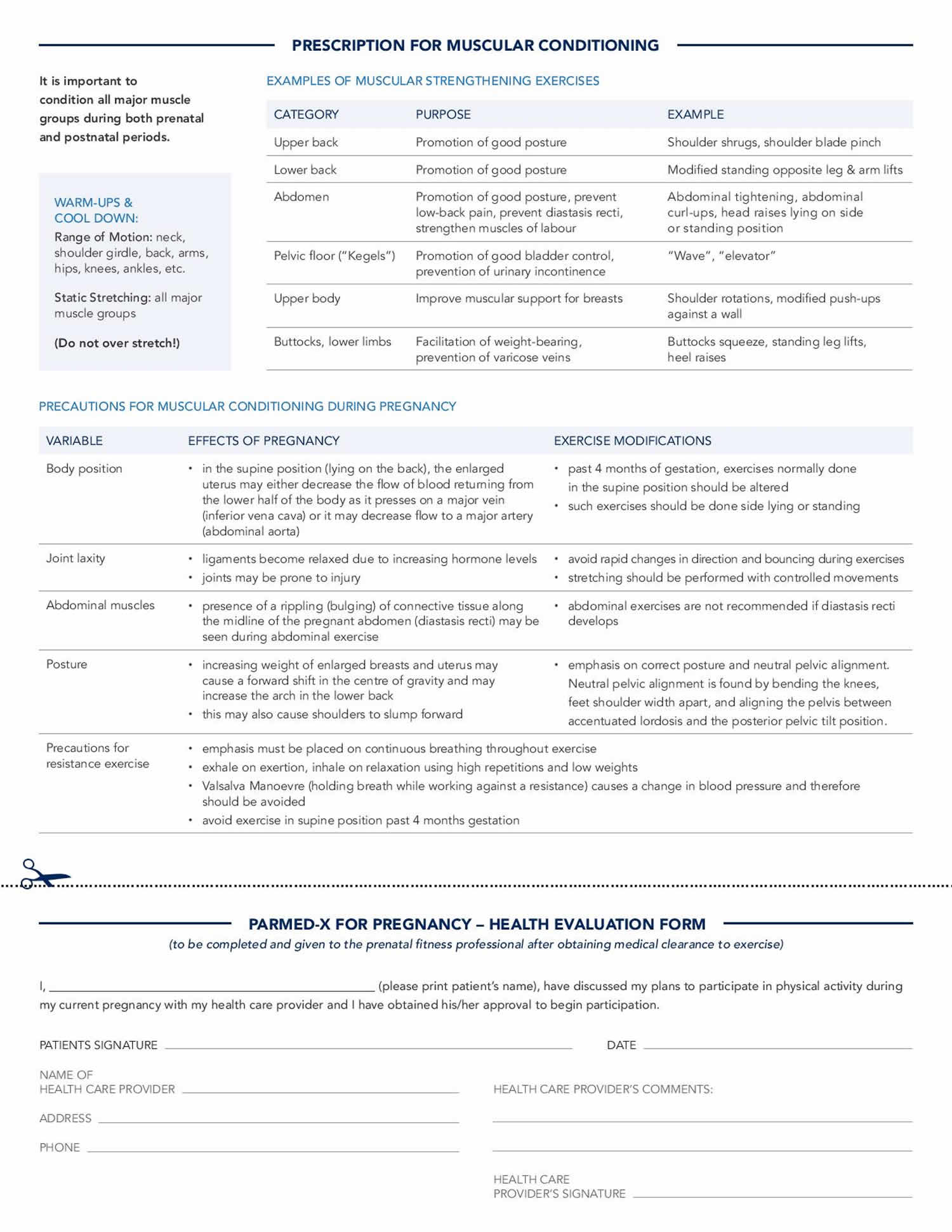

Exercise prescription for pregnancy

Healthy, pregnant women without exercise contraindications are encouraged to exercise throughout pregnancy 8. However, a woman who was sedentary before pregnancy or who has a medical condition should receive clearance from her physician or midwife before beginning an exercise program. Regular exercise during pregnancy provides health/fitness benefits to the mother and child 9. Exercise may also reduce the risk of developing conditions associated with pregnancy such as pregnancy-induced hypertension and gestational diabetes mellitus 10.

Women who are pregnant and healthy are encouraged to exercise throughout pregnancy with the exercise prescription modified according to symptoms, discomforts, and abilities. Women who are pregnant should exercise 3–4 days/week for 15 minutes/day gradually increasing to a maximum of 30 minutes/day for each exercise session, accumulating a total of 150 minutes/week of physical activity that includes the warm up and cool down. Moderate intensity exercise is recommended for women with a prepregnancy BMI 25 kg/m². Light intensity exercise is recommended for women with a prepregnancy BMI of 25 kg/m²

Special considerations

- Women who are pregnant and sedentary or have a medical condition should gradually increase physical activity levels to meet the recommended levels earlier as per preparticipation completion of the PARmed-X for Pregnancy (see Figure 1) 11.

- Women who are pregnant and severely obese and/or have gestational diabetes mellitus or hypertension should consult their physician before beginning an exercise program and have their exercise prescription adjusted to their medical condition, symptoms, and physical fitness level.

- Women who are pregnant should avoid contact sports and sports/activities that may cause loss of balance or trauma to the mother or fetus. Examples of sports/activities to avoid include soccer, basketball, ice hockey, roller blading, horseback riding, skiing/snow boarding, scuba diving, and vigorous intensity, racquet sports.

- Exercise should be terminated immediately with medical follow-up should any of these signs or symptoms occur: vaginal bleeding, dyspnea before exertion, dizziness, headache, chest pain, muscle weakness, calf pain or swelling, preterm labor, decreased fetal movement (once detected), and amniotic fluid leakage 8. In the case of calf pain and swelling, thrombophlebitis should be ruled out.• Women who are pregnant should avoid exercising in the supine position after 16 wk of pregnancy to ensure that venous obstruction does not occur 12.

- Women who are pregnant should avoid performing the Valsalva maneuver during exercise.

- Women who are pregnant should avoid exercising in a hot humid environment, be well hydrated, and dressed appropriately to avoid heat stress.

- During pregnancy, the metabolic demand increases by 300 kcal/day. Women should increase caloric intake to meet the caloric costs of pregnancy and exercise. To avoid excessive weight gain during pregnancy, consult appropriate weight gain guidelines based on prepregnancy BMI available from the Institute of Medicine and the National Research Council 13.

- Women who are pregnant may participate in a strength training program that incorporates all major muscle groups with a resistance that permits multiple submaximal repetitions (i.e., 12–15 repetitions) to be performed to a point of moderate fatigue. Isometric muscle actions and the Valsalva maneuver should be avoided as should the supine position after 16 weeks of pregnancy 12. Kegel exercises and those that strengthen the pelvic floor are recommended to decrease the risk of incontinence 14.

- Generally, gradual exercise in the postpartum period may begin 4–6 weeks after a normal vaginal delivery or about 8–10 weeks (with medical clearance) after a cesarean section delivery 14. Deconditioning typically occurs during the initial postpartum period so women should gradually increase physical activity levels until prepregnancy physical fitness levels are achieved. Light-to-moderate intensity exercise does not interfere with breast feeding 14.

Figure 1. PARmed-X for Pregnancy. Physical Activity Readiness Medical Examination

Contraindications for exercising during pregnancy

Absolute contraindications 8:

- Hemodynamically significant heart disease

- Restrictive lung disease

- Incompetent cervix/cerclage

- Multiple gestation at risk for premature labor

- Persistent second or third trimester bleeding

- Placenta previa after 26 weeks of gestation

- Premature labor during the current pregnancy

- Ruptured membranes

- Preeclampsia/pregnancy-induced hypertension

- Unexplained persistent vaginal bleeding,

- Intrauterine growth restriction in current pregnancy

- High-order multiple pregnancy (e.g., triplets)

- Uncontrolled or poorly controlled Type 1 diabetes mellitus

- Uncontrolled hypertension

- Uncontrolled thyroid disease

- Other serious cardiovascular, respiratory or systemic disorder.

Relative contraindications 8:

- Severe anemia

- Unevaluated maternal cardiac dysrhythmia

- Chronic bronchitis

- Extreme morbid obesity

- Extreme underweight or malnutrition

- Eating disorder

- History of extremely sedentary lifestyle

- Orthopedic limitations

- Poorly controlled seizure disorder

- Poorly controlled hyperthyroidism

- Heavy smoker

- Recurrent pregnancy loss

- Gestational hypertension

- A history of spontaneous preterm birth

- Mild/moderate cardiovascular or respiratory disease

- Twin pregnancy after the 28th week

- Other significant medical conditions.

FITT recommendations for women who are pregnant

Aerobic Exercise

- Frequency: 3–4 days/week. Research suggests an ideal frequency of 3–4 days/week because frequency has been shown to be a determinant of birth weight. Women who do not exercise within the recommended frequency (i.e., 5 days/week or 2 days/week) increase their risk of having a low-birth-weight baby 15. Infants with a low birth weight for gestational age are at risk for perinatal complications and developmental problems 15, thus prevention of low birth weight is an important health goal.

- Intensity: Because maximal exercise testing is rarely performed with women who are pregnant, heart rate (HR) ranges that correspond to moderate intensity exercise have been developed and validated for low-risk pregnant women based on age while taking fitness levels into account 12. Moderate intensity exercise is recommended for women with a prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) 25 kg/m². Light intensity exercise is recommended for women with a prepregnancy BMI 25 kg/m² 16.

- Time: 15 minutes/day gradually increasing to a maximum of 30 minutes/day of accumulated moderate intensity exercise to total 120 minutes/week. A 10–15 minutes warm-up and a 10–15 minutes cool-down of light intensity, physical activity is suggested before and after the exercise session, respectively 12, resulting in approximately 150 minutes/week of accumulated exercise. Women with a prepregnancy BMI of 25 kg/m² who have been medically prescreened can exercise at a light intensity starting at 25 minutes/day, adding 2 minutes/week until 40 minutes 3–4 days/week is achieved 17.

- Type: Dynamic, rhythmic physical activities that use large muscle groups such as walking and cycling.

- Progression: The optimal time to progress is after the first trimester (13 week) because the discomforts and risks of pregnancy are lowest at that time. Gradual progression from a minimum of 15 minutes/day, 3 days/week (at the appropriate target heart rate or rating of perceived exertion) to a maximum of approximately 30 minutes/day, 4 days/week (at the appropriate target heart rate or rating of perceived exertion) 12.

- Balady GJ, Williams MA, Ades PA, et al. Core components of cardiac rehabilitation/secondary prevention programs: 2007 update: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Exercise, Cardiac Rehabilitation, and Prevention Committee, the Council on Clinical Cardiology; the Councils on Cardiovascular Nursing, Epidemiology and Prevention, and Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism; and the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. Circulation. 2007 May 22. 115(20):2675-82.

- Moore GE. The role of exercise prescription in chronic disease. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38:6–7. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2003.010314

- Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39(8):1423–34.

- Seth A. Exercise prescription: what does it mean for primary care?. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64(618):12-13. doi:10.3399/bjgp14X676294 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3876165

- Department of Health . Start Active, Stay Active: A report on physical activity from the four home countries’ Chief Medical Officers. London: Department of Health; 2011.

- Jensen MT, Suadicani P, Hein HO, et al. Elevated resting heart rate, physical fitness and all-cause mortality: a 16-year follow-up in the Copenhagen Male Study. Heart 2013;99:882-887. https://heart.bmj.com/content/heartjnl/99/12/882.full.pdf

- All About Heart Rate (Pulse). https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/high-blood-pressure/the-facts-about-high-blood-pressure/all-about-heart-rate-pulse

- ACOG Committee Obstetric Practice. ACOG Committee opinion. Number 267, January 2002: exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(1):171–3.

- Dempsey JC, Butler CL, Williams MA. No need for a pregnant pause: physical activity may reduce the occurrence of gestational diabetes mellitus and preeclampsia. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2005;33(3):141–9.

- Impact of physical activity during pregnancy and postpartum on chronic disease risk. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(5):989–1006.

- PARmed-X for Pregnancy. Physical Activity Readiness Medical Examination. http://www.csep.ca/cmfiles/publications/parq/parmed-xpreg.pdf

- Davies GA, Wolfe LA, Mottola MF, et al. Joint SOGC/CSEP clinical practice guideline: exercise in pregnancy and the postpartum period. Can J Appl Physiol. 2003;28(3):330–41.

- Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guideline. Report Brief [Internet]. Washington (DC): National Academy of Sciences; 2009 [cited 2011 Jan 13]. 4 p. Available from: http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2009/Weight-Gain-During-Pregnancy-Reexamining-the-Guidelines.aspx

- Mottola MF. Exercise in the postpartum period: practical applications. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2002;1(6):362–8.

- Campbell MK, Mottola MF. Recreational exercise and occupational activity during pregnancy and birth weight: a case-control study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184(3):403–8.

- Davenport MH, Charlesworth S, Vanderspank D, Sopper MM, Mottola MF. Development and valida-tion of exercise target heart rate zones for overweight and obese pregnant women. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2008;33(5):984–9.

- Mottola MF, Giroux I, Gratton R, et al. Nutrition and exercise prevent excess weight gain in over-weight pregnant women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42(2):265–72.