Fungal meningitis

Fungal meningitis is an inflammation of the brain and spinal cord lining, and fungal meningitis occurs when the membranes protecting the brain and spinal cord become infected with fungus that spreads from somewhere else in your body to your brain or spinal cord. Fungal meningitis is rare in the United States and causes chronic meningitis. Some causes of fungal meningitis include Cryptococcus, Histoplasma, Blastomyces, Coccidioides, and Candida. The most common type of fungal meningitis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans or cryptococcal meningitis that affects people with immune deficiencies, such as AIDS. It’s life-threatening if not treated with an antifungal medication. Fungal meningitis may mimic acute bacterial meningitis. Fungal meningitis isn’t contagious from person to person. Fungal meningitis occurs most commonly in immunosuppressed individuals and is often accompanied by systemic involvement 1. Signs and symptoms of fungal meningitis may include the following: fever, headache, stiff neck, nausea and vomiting, sensitivity to light (photophobia), altered mental status (confusion), weakness and numbness.

Fungal meningitis causes

Certain fungi that can cause meningitis live in the environment:

- Cryptococcus lives in soil, on decaying wood, and in bird droppings throughout the world.

- Cryptococcus neoformans fungus causes most cases of fungal meningitis.

- Histoplasma lives in environments with large amounts of bird or bat droppings. In the United States, the fungus mainly lives in the central and eastern states.

- Blastomyces lives in moist soil and in decaying wood and leaves. In the United States, the fungus mainly lives in midwestern, south central, and southeastern states.

- Coccidioides lives in the soil in the southwestern United States and areas of Central and South America.

These fungi are too small to see without a microscope. People can get sick if they breathe in fungal spores. People get meningitis if the fungal infection spreads from the lungs to the brain or spinal cord. Fungal meningitis does not spread between people.

The fungus Candida can also cause meningitis. Candida normally lives inside the body and on the skin without causing any problems. However, in certain patients who are at risk, Candida can enter the bloodstream or internal organs and cause an infection.

Risk factors for fungal meningitis

Although anyone can get fungal meningitis, people with weakened immune systems are at increased risk. Certain health conditions, medications, and surgical procedures may weaken the immune system. HIV infection and cancer are examples of health conditions that can weaken the immune system. Medications that can weaken the immune system include:

- Steroids (such as prednisone)

- Medications given after organ transplantation

- Anti-TNF medications, which are sometimes given for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis or other autoimmune conditions

Premature babies with very low birth weights are also at increased risk for getting Candida bloodstream infection, which may spread to the brain.

Living in certain areas of the United States may increase the risk for fungal lung infections, which can cause meningitis.

Fungal meningitis prevention

No specific activities are known to cause fungal meningitis. People with weak immune systems should try to avoid

- Large amounts of bird or bat droppings

- Digging in soil

- Dusty activities

This is especially true if they live in a geographic region where fungi like Histoplasma, Coccidioides, or Blastomyces exist.

Cryptococcal meningitis

Cryptococcal meningitis is the most common cause of adult meningitis—particularly in regions with high HIV burden—and is a growing cause of concern around the world 2. Caused by Cryptococcus neoformans or Cryptococcus gattii, cryptococcal meningitis manifests when a cryptococcal infection disseminates to the central nervous system (CNS) and is associated with an uncertain prognosis 3. Cryptococcal meningitis in most cases is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans fungus. Cryptococcus neoformans fungus is commonly found in the environment, including the soil around the world. People can become infected with Cryptococcus neoformans after breathing in the microscopic fungus, although most people who are exposed to the fungus never get sick from it. Cryptococcus neoformans infections are rare in people who are otherwise healthy; most cases occur in people who have weakened immune systems, particularly those who have advanced HIV/AIDS. Cryptococcal meningitis is not spread from person to person. Usually, it spreads through the bloodstream to the brain from another place in the body that has the infection.

Cryptococcal meningitis most often affects people with a weakened immune system, including people with:

- AIDS

- Cirrhosis (a type of liver disease)

- Diabetes

- Leukemia

- Lymphoma

- Sarcoidosis

- An organ transplant

Cryptococcal meningitis is rare in people who have a normal immune system and no long-term health problems.

Cryptococcal infections were reported in fewer than 500 patients globally prior to the 1960s, but clinicians witnessed a dramatic rise during the early AIDS pandemic of the 1980s, with over 330 cases per year in the United States alone 4. As the HIV pandemic grew, cryptococcal meningitis followed. HIV is the largest risk factor for cryptococcal meningitis and is associated with up to 79 % of cryptococcal meningitis cases. Cryptococcal meningitis accounts for up to 15–17 % of AIDS-related mortality, even in resource-available settings 5. Over the last decade, approximately 1 million cases were diagnosed on an annual basis worldwide, with approximately 700 000 deaths per year, up to 500 000 of which occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa alone 2. With the increasing availability of more widespread antiretroviral therapy (ART) for treatment of HIV infection, the burden of cryptococcal meningitis has decreased modestly worldwide. In fact, the most recent estimates indicate around 200,000 new cases per year, with 120,000 deaths 6. However, a sobering study showed that with ART availability in sub-Saharan Africa cases of cryptococcosis have levelled off at what is still a high rate 7. Moreover, while the rate of undiagnosed HIV is decreasing in the United States, it is still the case that cryptococcal meningitis is commonly diagnosed late in the disease process among socio-economically disadvantaged populations and those with less obvious risk factors, which leads to potentially worse outcomes 8. HIV-negative and non-transplant cryptococcal meningitis is a less common but significant problem, with a high rate of mortality (20–30 %) despite available therapy 5. Of the HIV-uninfected patients, one large series identified 25 % of cryptococcal meningitis patients as receiving steroid therapy, 24 % with chronic kidney, liver, or lung disease, 16 % with a malignancy and 15 % with solid-organ transplants 9. However, when HIV infection is excluded, up to 30 % of cryptococcal meningitis cases can occur in apparently immunocompetent individuals with no underlying disease 9, and they are commonly caused by Cryptococcus gattii 10.

Cryptococcal meningitis symptoms

Cryptococcal meningitis symptoms

Cryptococcal meningitis starts slowly, over a few days to a few weeks. Symptoms may include:

- Fever

- Hallucinations

- Headache

- Mental status change (confusion)

- Nausea and vomiting

- Sensitivity to light

- Stiff neck

Symptoms do not come on suddenly as with acute bacterial meningitis but appear gradually.

Cryptococcal meningitis diagnosis

Healthcare providers rely on your medical history, symptoms, physical examinations, and laboratory tests to diagnose cryptococcal meningitis. Your health care provider will examine you and ask about your symptoms.

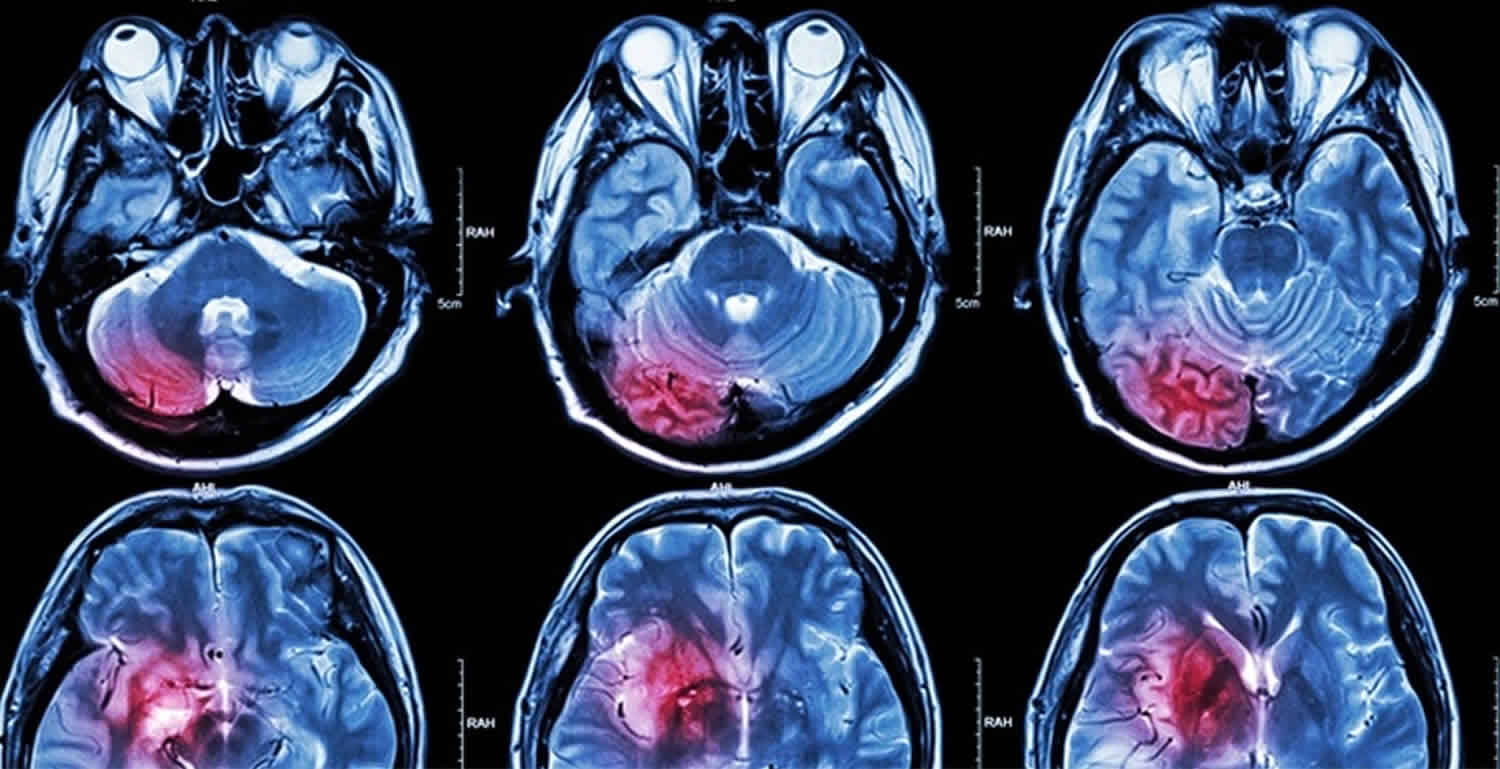

Your healthcare provider will take a sample of tissue or body fluid (such as blood, cerebrospinal fluid, or sputum) and send the sample to a laboratory to be examined under a microscope, tested with an antigen test, or cultured. Your healthcare provider may also perform tests such as a chest x-ray or CT scan of your lungs, brain, or other parts of the body.

A lumbar puncture (spinal tap) is used to diagnose meningitis. In this test, a sample of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is removed from your spine and tested.

Lab tests that may be done include:

- Blood culture

- Chest x-ray

- Cryptococcal antigen in CSF or blood, to look for antibodies

- CSF examination for cell count, glucose, and protein

- CT scan of the head

- Gram stain, other special stains, and culture of CSF

Culture: The gold standard for diagnosing cryptococcal infection; culture is traditionally identify Cryptococcus from human body samples.

Microscopy: India Ink can be performed on CSF to quickly visualize Cryptococcus cells under a microscope; however, it can have limited sensitivity. Histopathology for detection of narrow-based budding yeasts in tissue can also be used.

Antigen detection: Can be used on CSF or serum for detection of early, asymptomatic cryptococcal infection in HIV-infected patients; higher sensitivity than microscopy or culture.

- Latex agglutination (LA)

- Enzyme immunoassay (EIA)

- Lateral flow assay (LFA)

Cryptococcal meningitis treatment

Treatment is with antifungal medication, for instance or amphotericin B, flucytosine and fluconazole. Many patients will need “maintenance therapy” – which means they will have to continue taking medication indefinitely.

For people who have severe lung infections or cryptococcal meningitis, the recommended initial treatment is amphotericin B in combination with flucytosine. After that, patients usually need to take fluconazole for an extended time to clear the infection.

The type, dose, and duration of antifungal treatment may differ for certain groups of people, such as pregnant women, children, and people in resource-limited settings. Some people may also need surgery to remove fungal growths (cryptococcomas).

Infectious Diseases Society of America’s Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Cryptococcal Disease 11. Candida infection is known to disseminate to the central nervous system (CNS) in immunocompromised patients or in the setting of anatomic abnormalities 12. Notably, candida meningitis is most common in infants with an immature blood brain barrier (BBB), while Candida albicans is the most common fungal isolate from both newborn and infant CSF 13. Moreover, neonates who develop candidaemia are at greater risk for brain and spinal cord (central nervous system) dissemination of the disease than adults 14. Neurosurgical procedures also breach the blood brain barrier (BBB) and offer an opportunity for direct inoculation of the CNS with yeasts 15. In fact, candida meningitis is the most common fungal meningitis for patients with ventriculoperitoneal shunts or ventriculostomies and often occurs with concurrent post-surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis 16. The mortality associated with untreated candida meningitis ranges from 50–97 % 17. After treatment, mortality decreases to 10–30 %, with percentages varying by risk group 17.

Because infants are a particularly at-risk population, studies from other groups have identified the incidence of candida meningitis in neonates as 0.4%, and 1.1 % in infants weighing <1500 g at birth. Importantly, the mortality rate in infants varies from 12–35 % 14. Another study of premature infants identified a 44 % mortality rate from candida meningitis, with 60 % combined mortality and developmental disabilities, versus 28 % in age-matched controls 18.

Coccidioidal meningitis

Coccidioides meningitis is the result of disseminated coccidioidomycosis, caused by the sibling dimorphic fungi, Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii, with geographical boundaries 19. The incidence of coccidioidomycosis within the United States has been increasing since 1998, and was last reported at 42.6 per 100 000 in 2011, with 66 % of cases occurring in Arizona and 31 % in California 20. Approximately 1 to 3 % of coccidioidomycosis cases disseminate 20, and within the first few months after acute primary infection 33 to 50 % develop meningitis 15. Similar to other types of fungal meningitis, it is likely that immunosuppressed individuals are at higher risk for coccidioides meningitis 20. However, Bronnimann and colleagues 21 linked only 2 % of coccidioides meningitis cases with immunosuppressive therapy or HIV infection prior to disease onset, indicating far less influence from immune suppression than other forms of fungal meningitis and suggesting a potential genetic role in meningitis risk 15. For instance, any individual may experience disseminated coccidioidomycosis, but the risk of dissemination seems to be higher in Filipinos, African Americans, diabetics and third trimester pregnancy individuals 22. Coccidioides meningitis may result in severe and fatal complications if not identified and treated immediately 23. Coccidioides meningitis is uniformly fatal without any treatment 24, but current antifungal regimens cannot reliably cure coccidioides meningitis 25. With the advent of antifungal treatment, the mortality rate has dropped to ~30 %, but morbidity remains unchanged 26.

Histoplasma meningitis

Histoplasma meningitis is a geographical fungal infection caused by the dimorphic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum and is endemic to certain areas within the United States, South America, Southeast Asia and Africa 27. Immunocompromised individuals are at risk for developing lethal progressive disseminated histoplasmosis 28. Specifically, histoplasma meningitis occurs in AIDS patients, solid-organ transplant recipients, and patients taking corticosteroids or TNF-α antagonists 29. Wilson et al. 30 reported a total of 4950 diagnosed cases of histoplasmosis in 1994, with an incidence of 19.02 per million of the US population, and 3681 patients diagnosed with histoplasmosis in 1996, with an incidence of 13.62 per million of the US population. In a clinical review of Histoplasma capsulatum, Wheat et al. 31 identified CNS manifestation in 10–20 % of disseminated histoplasmosis cases. The mortality rate for those with CNS involvement was 20–40 %, with a relapse rate of 50 % in those who survive 32.

Fungal meningitis symptoms

Symptoms of fungal meningitis are similar to symptoms of other types of meningitis. However, they often appear more gradually and can be very mild at first. Early meningitis symptoms may mimic the flu (influenza). Symptoms may develop over several hours or over a few days.

Meningitis symptoms can appear in any order. Some may not appear at all. Early symptoms of meningitis in adults and children can include:

- fever, headache, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle pain, stomach cramps, fever with cold hands and feet

Possible signs and symptoms of fungal meningitis in anyone older than the age of 2 include:

- Sudden high fever

- Stiff neck

- Severe headache that seems different than normal

- Headache with nausea or vomiting

- Confusion or difficulty concentrating

- Seizures

- Sleepiness or difficulty waking

- Sensitivity to light

- No appetite or thirst

- Skin rash

Signs in newborns

Newborns and infants may show these signs:

- High fever

- Constant crying

- Excessive sleepiness or irritability

- Inactivity or sluggishness

- Poor feeding

- A bulge in the soft spot on top of a baby’s head (fontanel)

- Stiffness in a baby’s body and neck

Infants with meningitis may be difficult to comfort, and may even cry harder when held.

Seek immediate medical care if you or someone in your family has meningitis symptoms, such as:

- Fever

- Severe, unrelenting headache

- Confusion

- Vomiting

- Stiff neck

Fungal meningitis diagnosis

If a doctor suspects meningitis, he or she may collect samples of blood or cerebrospinal fluid (fluid surrounding the spinal cord). Then laboratories can perform specific tests, depending on the type of fungus suspected. Knowing the cause of fungal meningitis is important because doctors treat different types of fungi differently.

Fungal meningitis treatment

Doctors treat fungal meningitis with long courses of high-dose antifungal medications, usually given directly into a vein through an IV in the hospital. After that, patients also need to take antifungal medications by mouth. The total length of treatment depends on the patient’s immune system and the type of fungus causing the infection. Treatment is often longer for people with weak immune systems, like those with AIDS or cancer. For people with immune systems that do not function well because of other conditions, such as HIV infection, diabetes or cancer, treatment is often longer.

References- Fungal meningitis. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-us/541

- Williamson PR, Jarvis JN, Panackal AA, Fisher MC, Molloy SF, et al. Cryptococcal meningitis: epidemiology, immunology, diagnosis and therapy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13:13–24. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2016.167

- Park BJ, Wannemuehler KA, Marston BJ, Govender N, Pappas PG, et al. Estimation of the current global burden of cryptococcal meningitis among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 2009;23:525–530. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328322ffac

- Banerjee U, Datta K, Majumdar T, Gupta K. Cryptococcosis in India: the awakening of a giant? Med Mycol. 2001;39:51–67.

- Pyrgos V, Seitz AE, Steiner CA, Prevots DR, Williamson PR. Epidemiology of cryptococcal meningitis in the US: 1997-2009. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056269

- Rajasingham R, Smith RM, Park BJ, Jarvis JN, Govender NP, et al. Global burden of disease of HIV-associated cryptococcal meningitis: an updated analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:873–881. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30243-8

- Friedman GD, Jeffrey Fessel W, Udaltsova NV, Hurley LB. Cryptococcosis: the 1981–2000 epidemic. Mycoses. 2005;48:122–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2004.01082.x

- Mirza SA, Phelan M, Rimland D, Graviss E, Hamill R, et al. The changing epidemiology of cryptococcosis: an update from population-based active surveillance in 2 large metropolitan areas, 1992-2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:789–794. doi: 10.1086/368091

- Pappas PG, Perfect JR, Cloud GA, Larsen RA, Pankey GA, et al. Cryptococcosis in human immunodeficiency virus-negative patients in the era of effective azole therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:690–699. doi: 10.1086/322597

- Gottfredsson M, Perfect JR. Fungal meningitis. Semin Neurol. 2000;20:307–322. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9394

- )John R. Perfect, William E. Dismukes, Francoise Dromer, David L. Goldman, John R. Graybill, Richard J. Hamill, Thomas S. Harrison, Robert A. Larsen, Olivier Lortholary, Minh-Hong Nguyen, Peter G. Pappas, William G. Powderly, Nina Singh, Jack D. Sobel, Tania C. Sorrell, Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Cryptococcal Disease: 2010 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 50, Issue 3, 1 February 2010, Pages 291–322, https://doi.org/10.1086/649858).

Cryptococcal meningitis prognosis

People who recover from cryptococcal meningitis need long-term medicine to prevent the infection from coming back. People with weakened immune systems, such as those with HIV/AIDS, will also need long-term treatment to improve their immune system.

Possible complications

These complications may occur from cryptococcal meningitis:

- Brain damage

- Hearing or vision loss

- Hydrocephalus (excessive CSF in the brain)

- Seizures

- Death

Amphotericin B can have side effects such as:

- Nausea and vomiting

- Fever and chills

- Joint and muscles aches

- Kidney damage

Candida meningitis

Candida meningitis is a fungal infection of the brain and spinal cord (central nervous system) caused by several Candida species, including Candida albicans, Candida tropicalis, Candida lusitaniae and Candida parapsilosis, which are distributed worldwide and are encountered in patients globally ((Gottfredsson M, Perfect JR. Fungal meningitis. Semin Neurol. 2000;20:307–322. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9394.

- Chadwick DW, Hartley E, MacKinnon DM. Meningitis caused by Candida tropicalis. Arch Neurol. 1980;37:175–176.

- Bouza E, Dreyer JS, Hewitt WL, Meyer RD. Coccidioidal meningitis. An analysis of thirty-one cases and review of the literature. Medicine. 1981;60:139–172.

- Fernandez M, Moylett EH, Noyola DE, Baker CJ. Candidal meningitis in neonates: a 10-year review. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:458–463. doi: 10.1086/313973

- Gottfredsson M, Perfect JR. Fungal meningitis. Semin Neurol. 2000;20:307–322. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-9394.

- Poon WS, Ng S, Wai S. CSF antibiotic prophylaxis for neurosurgical patients with ventriculostomy: a randomised study. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 1998;71:146–148.

- Henao N. Infections of the central nervous system by Candida. J Infect Dis Immun. 2011;3:79–84.

- Lee BE, Cheung PY, Robinson JL, Evanochko C, Robertson CM. Comparative study of mortality and morbidity in premature infants (birth weight, < 1,250 g) with candidemia or candidal meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:559–565.

- Charalambous LT, Premji A, Tybout C, et al. Prevalence, healthcare resource utilization and overall burden of fungal meningitis in the United States. J Med Microbiol. 2018;67(2):215–227. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.000656 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6557145

- Stockamp NW, Thompson GR. Coccidioidomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2016;30:229–246. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2015.10.008

- Bronnimann DA, Adam RD, Galgiani JN, Habib MP, Petersen EA, et al. Coccidioidomycosis in the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:372–379. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-106-3-372

- Rouhani AA. Infectious disease/CDC update. Update on emerging infections: news from the centers for disease control and prevention. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;67:131–134. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.10.008

- Holmquist L, Russo CA, Elixhauser A. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006. Meningitis-related hospitalizations in the United States, 2006. HCUP Statistical Brief #57, July 2008.

- Vincent T, Galgiani JN, Huppert M, Salkin D. The natural history of coccidioidal meningitis: VA-Armed Forces cooperative studies, 1955-1958. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;16:247–254.

- Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Blair JE, Catanzaro A, Geertsma F, et al. 2016 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guideline for the treatment of Coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:e112-146. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw538

- Johnson RH, Einstein HE. Coccidioidal meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:103–107. doi: 10.1086/497596

- Schuster JE, Wushensky CA, di Pentima MC. Chronic primary central nervous system histoplasmosis in a healthy child with intermittent neurological manifestations. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2013;32:794–796. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31828d293e

- Bradsher RW. Histoplasmosis and blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;22:S102–S111. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.Supplement_2.S102

- Zarrin M, Mahmoudabadi AZ. Central nervous system fungal infections; a review article. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2010;3:41–47.

- Wilson LS, Reyes CM, Stolpman M, Speckman J, Allen K, et al. The direct cost and incidence of systemic fungal infections. Value Health. 2002;5:26–34. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4733.2002.51108.x

- Wheat LJ, Batteiger BE, Sathapatayavongs B. Histoplasma capsulatum infections of the central nervous system. A clinical review. Medicine. 1990;69:244–260. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199007000-00006

- Hariri OR, Minasian T, Quadri SA, Dyurgerova A, Farr S, et al. Histoplasmosis with deep CNS involvement: case presentation with discussion and literature review. J Neurol Surg Rep. 2015;76:e167-172. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1554932