Gallbladder cancer

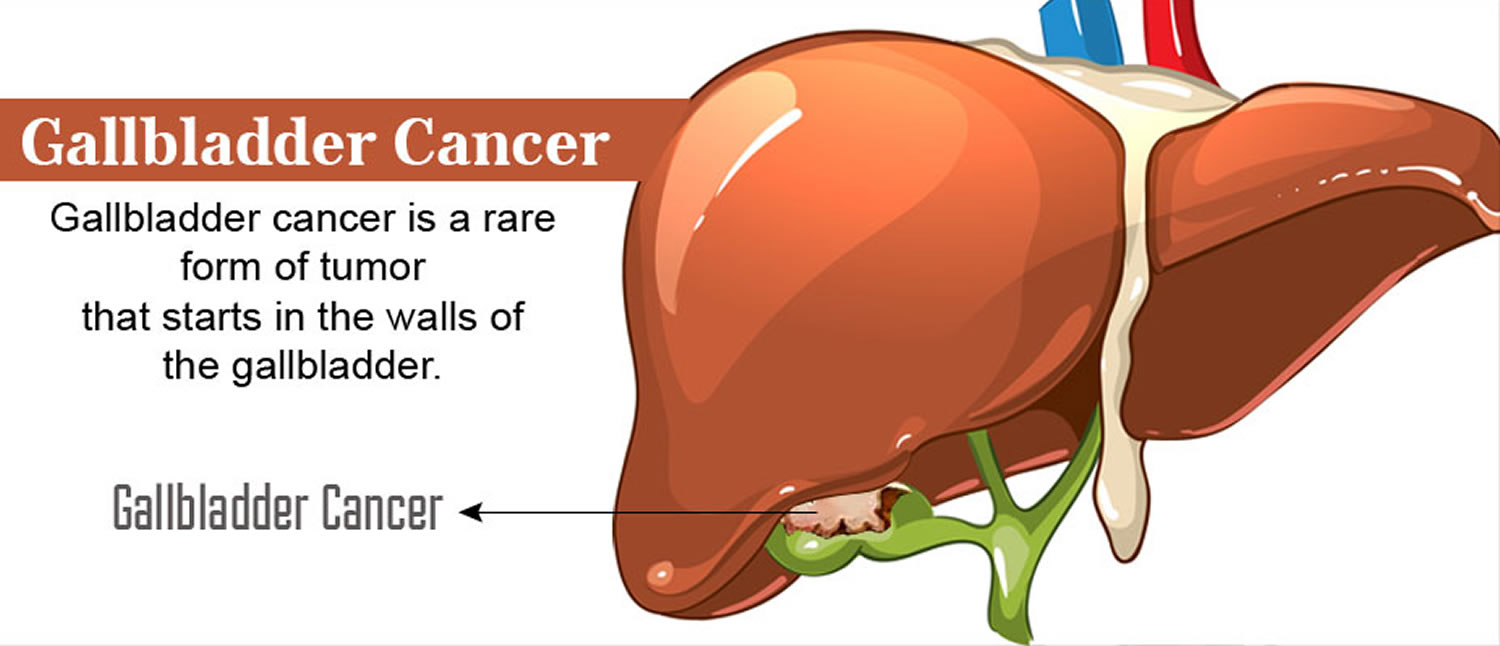

Gallbladder cancer is a rare cancer that begins in the gallbladder. The gallbladder is a small, hollow, pear-shaped pouch about 8cm long and about 2.5cm wide. The gallbladder lies underneath the right side of your liver, in your upper abdomen (see Figures 1 to 4). Bile (a digestive fluid produced by your liver) is concentrated and stored in your gallbladder.

The American Cancer Society’s estimates for cancer of the gallbladder and nearby large bile ducts in the United States for 2022 are 1:

- About 12,130 new cases diagnosed: 5,710 in men and 6,420 in women

- About 4,400 deaths from gallbladder cancers: 1,830 in men and 2,570 in women

Of these new cases, a little less than 4 in 10 will be gallbladder cancers. Gallbladder cancer is more common in women than in men. In the United States, gallbladder cancer occurs 3 to 4 times more often in women than in men. Gallstones and gallbladder inflammation are important risk factors for gallbladder cancer and are also much more common in women than men.

Gallbladder cancer is not usually found until it has become advanced and causes symptoms. Only about 1 of 5 gallbladder cancers is found in the early stages, when the cancer has not yet spread outside the gallbladder.

The chances of survival for patients with gallbladder cancer depend to a large extent on how advanced it is when it is found.

Gallbladder cancer is uncommon, but represents almost 50% of all biliary tract cancer 2. When gallbladder cancer is discovered at its earliest stages, the chance for a cure is very good. But most gallbladder cancers are discovered at a late stage, when the prognosis is often very poor.

Gallbladder cancer is difficult to diagnose because it often causes no specific signs or symptoms. Also, the relatively hidden nature of the gallbladder makes it easier for gallbladder cancer to grow without being detected.

Gallbladder cancer is often found when someone is having treatment for another condition, such as gallstones.

The Gallbladder

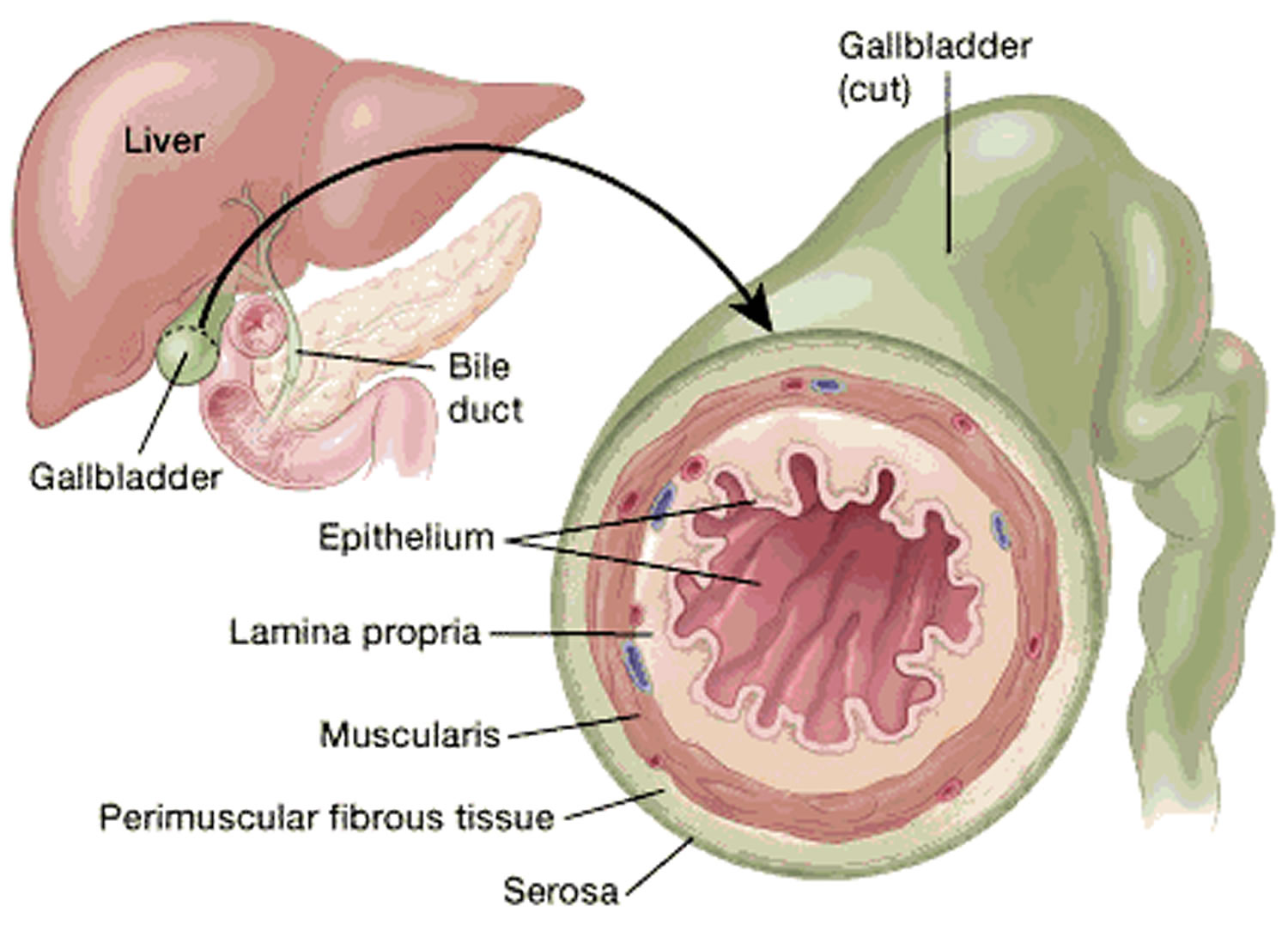

The gallbladder is a pear-shaped sac about 8cm long and about 2.5cm wide that lie in a depression on the right side of your liver’s under surface (Figure 1). The gallbladder is lined with epithelial cells and has a strong layer of smooth muscle in its wall. The gallbladder stores bile between meals, reabsorbs water to concentrate bile, and contracts to release bile into the small intestine. The gallbladder connects to the cystic duct, which in turn joins the common hepatic duct which comes from the liver (Figure 2). The gallbladder and bile ducts form your biliary tract. This is called the biliary tree or biliary system.

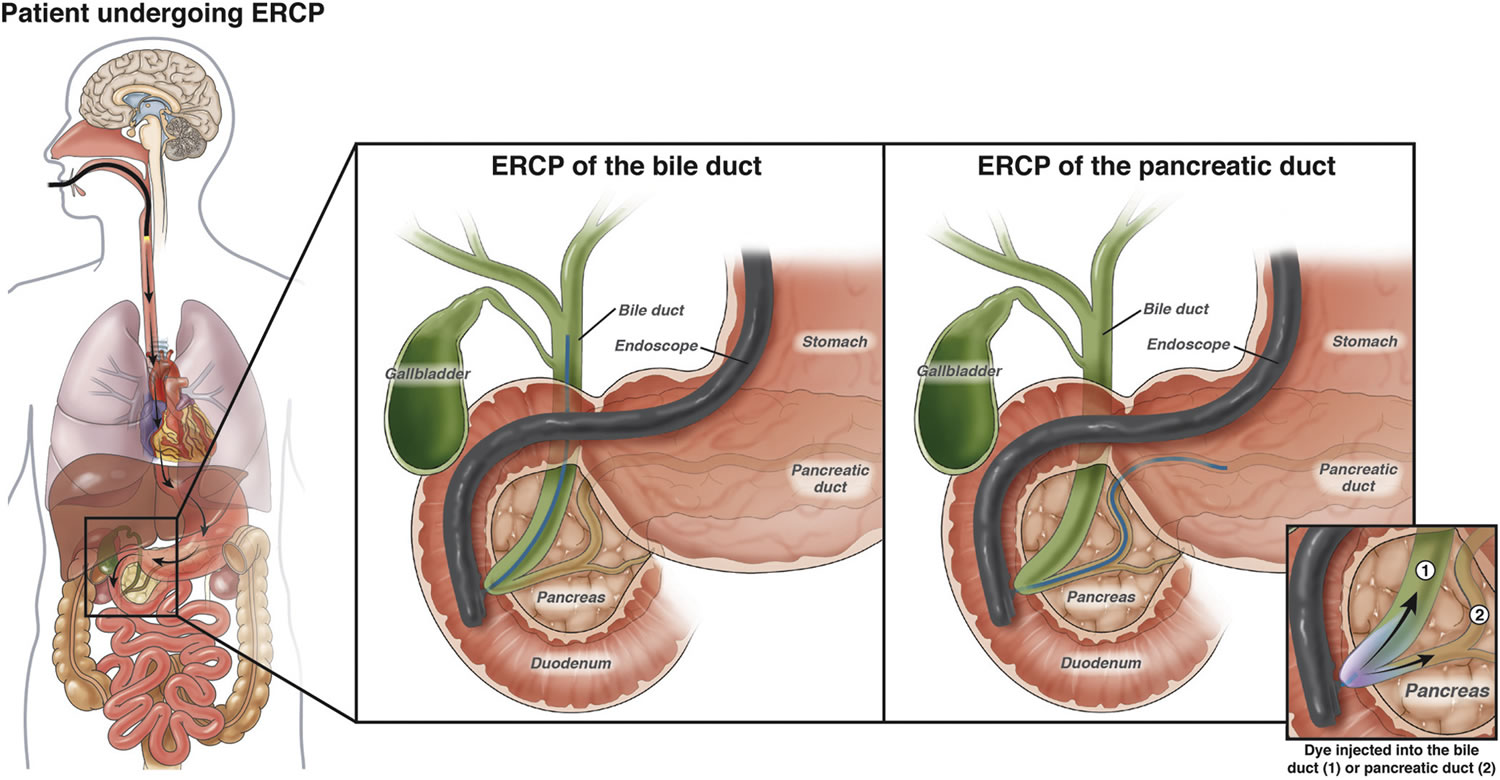

The common hepatic duct and cystic duct join to form the bile duct (common bile duct). The common bile duct joins with the main duct from the pancreas (the pancreatic duct) to empty into the first part of the small intestine (the duodenum) where the hepatopancreatic sphincter guards its exit at the ampulla of Vater (also known as hepatopancreatic ampulla) (Figure 3). Because this sphincter normally remains contracted, bile collects in the bile duct. It backs up into the cystic duct and flows into the gallbladder, where it is stored.

The gallbladder is helpful, but you do not need it to live. Many people have their gallbladders removed and go on to live normal lives. So after having it taken out, you’re still able to digest your food.

Gallbladder function

Following a meal, the mixing movements of the stomach wall aid in producing a semifluid paste of food particles and gastric juice called chyme.

As chyme enters the duodenum (the proximal portion of the small intestine), accessory organs—the pancreas, liver, and gallbladder—add their secretions.

Bile is a yellowish-green liquid continuously secreted from hepatic (liver) cells. In addition to water, bile contains bile salts, bile pigments (bilirubin and biliverdin), cholesterol, and electrolytes. Of these, bile salts are the most abundant and are the only bile components that have a digestive function.

Bile helps you to break down (digest) fats in your small bowel (intestine). When you eat fatty foods, the fats are broken down (digested) in your stomach and intestines. To get the bile to the food in your gut, your body either:

- releases it from the liver and down the bile ducts, straight into your small intestine

- stores it first in your gallbladder, which releases bile into your common bile duct as you need it

Bile pigments are breakdown products of hemoglobin from red blood cells and are normally secreted in the bile.

Normally bile does not enter the duodenum until cholecystokinin stimulates the gallbladder to contract. Proteins and fats in chyme in the duodenum stimulate

the intestinal wall to release cholecystokinin. Cholecystokinin travels via the bloodstream to the pancreas also, where it stimulate the pancreas to release its pancreatic juice that has a high concentration of digestive enzymes.

The hepatopancreatic sphincter usually remains contracted until a peristaltic wave in the duodenal wall approaches it. Then the sphincter relaxes, and bile is squirted into the duodenum (see Figure 4).

Note: Cholecystokinin produced by the intestinal wall cells, in response to proteins and fats in the small intestine, decreases secretory activity of gastric glands and inhibits gastric motility; stimulates pancreas to secrete fluid with a high digestive enzyme concentration and stimulates gallbladder to contract and release bile.

Figure 1. Gallbladder location

Figure 2. Gallbladder anatomy

Figure 3. The common bile duct is closely associated with the pancreatic duct and the duodenum

Figure 4. Fatty chyme entering the duodenum stimulates the gallbladder to release bile

Types of gallbladder cancer

Types of gallbladder cancer

About 9 out of 10 gallbladder cancers are adenocarcinomas. An adenocarcinoma is a cancer that starts in cells with gland-like properties that line many internal and external surfaces of the body (including the inside the digestive system).

Papillary adenocarcinoma or just papillary cancer is a type of gallbladder adenocarcinoma that deserves special mention. When seen under a microscope, the cells in these gallbladder cancers are arranged in finger-like projections. In general, papillary cancers are not as likely to grow into the liver or nearby lymph nodes. They tend to have a better prognosis (outlook) than most other kinds of gallbladder adenocarcinomas. About 6% of all gallbladder cancers are papillary adenocarcinomas.

Other types of cancer, such as adenosquamous carcinomas, squamous cell carcinomas, small cell carcinomas, and sarcomas, can develop in the gallbladder, but these are uncommon.

The histologic types of gallbladder cancer include the following 3:

- Carcinoma in situ.

- Biliary intraepithelial neoplasia, high grade.

- Intracystic papillary neoplasm with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia.

- Mucinous cystic neoplasm with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia.

- Adenocarcinoma.

- Adenocarcinoma, biliary type.

- Adenocarcinoma, intestinal type.

- Adenocarcinoma, gastric foveolar type.

- Mucinous adenocarcinoma.

- Clear cell adenocarcinoma.

- Signet-ring cell carcinoma.

- Squamous cell carcinoma.

- Adenosquamous carcinoma.

- Undifferentiated carcinoma.

- High-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma.

- Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma.

- Mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinoma.

- Intraductal papillary neoplasm with an associated invasive carcinoma.

- Mucinous cystic neoplasm with an associated invasive carcinoma.

Gallbladder Adenocarcinoma

This is the most common type of gallbladder cancer. More than 90 out of every 100 gallbladder cancers (90%) are adenocarcinomas. The cancer starts in gland cells in the gallbladder lining. These gland cells normally produce mucus (thick fluid).

There are three types of adenocarcinomas of the gallbladder. You might hear your doctor talking about 4:

- Non papillary adenocarcinoma

- Papillary adenocarcinoma

- Mucinous adenocarcinoma

Only about 6 out of every 100 gallbladder cancers (6%) are papillary adenocarcinomas. They develop in the tissues that hold the gallbladder in place (connective tissues). Papillary adenocarcinoma type of gallbladder cancer is less likely to spread to the liver and nearby lymph nodes. Papillary adenocarcinoma tends to have a better outlook than most other types of gallbladder cancer 5.

With mucinous adenocarcinomas, the cancer cells are often in pools of mucus. Only about 1 or 2 out of every 100 gallbladder cancers (1 or 2%) are mucinous adenocarcinoma.

Gallbladder Squamous cell cancer

Squamous cell cancers develop from the skin like cells that form the lining of the gallbladder, along with the gland cells. They are treated in the same way as adenocarcinomas. Only about 5 out of every 100 gallbladder cancers (5%) are squamous cell cancers 5.

Gallbladder Adenosquamous cancer

Adenosquamous carcinomas are cancers that have both squamous cancer cells and glandular cancer cells. Your doctor might call this a mixed histology. These cancers are treated in the same way as adenocarcinomas.

Gallbladder Small cell cancer

Small cell carcinomas are also called oat cell carcinomas. This is because the cancer cells have a distinctive oat like shape.

Gallbladder Sarcoma

Sarcoma is the name for a cancer that affects the supportive or protecting tissues of the body, also called the connective tissues. Muscles, blood vessels and nerves are all connective tissues. So a cancer that begins in the muscle layer of the gallbladder is called a sarcoma.

Gallbladder Neuroendocrine tumor

Neuroendocrine tumors are rare cancers that grow from hormone producing tissues, usually in the digestive system. The most common type of neuroendocrine tumor is called carcinoid. Carcinoid tumors tend to grow slowly. They might not cause any symptoms for several years.

Lymphoma and melanoma

These are extremely rare types of gallbladder cancer. They are not necessarily treated in the same way as the other types. For example, lymphomas tend to respond well to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. So it is very unlikely that you would have surgery to treat a lymphoma.

Gallbladder cancer signs and symptoms

Gallbladder cancer doesn’t usually cause symptoms in its early stages. So by the time you know it’s there, it might be at a more advanced stage than some other types of cancer. At diagnosis, gallbladder cancer has often spread outside the gallbladder itself to areas nearby.

It can be difficult for doctors to feel if your gallbladder is swollen or tender when they examine you. The gallbladder lies behind other organs deep inside your body, so it can be difficult to feel. Many early stage cancers of the gallbladder are found by chance. For example, when someone is having their gallbladder taken out to treat gallstones.

You may get a number of symptoms with gallbladder cancer. Most of these happen in the later stages of the disease.

Other illnesses apart from gallbladder cancer can also cause these symptoms. Even so, it is important that you see your doctor. Whatever is causing your symptoms needs treating.

Some of the more common symptoms of gallbladder cancer are:

- Abdominal (belly) pain. Most people with gallbladder cancer will have abdominal pain. Some people describe it as a dragging feeling. If the cancer or gallstones block the bile duct, you will have a sharper pain. Most often this is in the upper right portion of the abdomen.

- Nausea and/or vomiting. People with gallbladder cancer sometimes have vomiting as a symptom. This is very common in the later stages of gallbladder cancer. Over half the people diagnosed with gallbladder cancer will feel or be sick quite often at some stage of their illness. This is usually fairly easy to control with anti sickness drugs.

- Jaundice. Jaundice is a yellowing of the skin and the white part of the eyes. If the cancer grows large enough to block the bile ducts, bile from the liver can’t drain into the intestines. This can cause bilirubin (a chemical in bile that gives it a yellow color) to build up in the blood and settle in different parts of the body. This can often be seen in the skin and eyes.

- Jaundice symptoms can include:

- yellowing skin and whites of the eyes

- severe itching in some people

- darkened urine

- pale colored stools (bowel movements)

- Jaundice symptoms can include:

The bile salts make your skin and the whites of your eyes look yellow, and your skin itch (doctors call this itching pruritis). They also make your urine darker than normal. Because the bile is not passing into your bowel, your stools will be much paler than normal.

Nearly half the people diagnosed with gallbladder cancer have jaundice. This is often a sign that the cancer is in its later stages.

Remember – having jaundice does not always mean you have cancer. A viral infection of the liver (hepatitis) is a much more common cause of jaundice than gallbladder cancer.

Lumps in the belly

If the cancer blocks the bile ducts, the gallbladder can swell to larger than normal. Gallbladder cancer can also spread to nearby parts of the liver. These can sometimes be felt by the doctor as lumps on the right side of the belly. They can also be detected by imaging tests such as an ultrasound.

Other symptoms

Less common symptoms of gallbladder cancer include:

- Loss of appetite (anorexia)

- Weight loss without dieting

- Swelling in the abdomen (belly)

- Fever

- Itchy skin

- Dark urine

- Light-colored or greasy stools

Gallbladder cancer is not common, and these symptoms and signs are more likely to be caused by something other than gallbladder cancer. For example, people with gallstones also have many of these symptoms. There are many far more common causes of abdominal pain than gallbladder cancer. And viral hepatitis (infection of the liver) is a much more common cause of jaundice. Still, if you have any of these problems, it’s important to see your doctor right away so the cause can be found and treated, if needed.

Can Gallbladder Cancer Be Found Early?

Gallbladder cancer is hard to find early. The gallbladder is deep inside the body, so early tumors can’t be seen or felt during routine physical exams. There are no blood tests or other tests that can reliably detect gallbladder cancers early enough to be useful as screening tests. (Screening is testing for cancer in people without any symptoms.) Because of this, most gallbladder cancers are found only after the cancer has grown enough to cause signs or symptoms.

Still, some gallbladder cancers are found before they have spread to other tissues and organs. Many of these early cancers are found unexpectedly when a person’s gallbladder is removed because of gallstones. When the gallbladder is looked at in the lab after it is removed, small cancers or pre-cancers that did not cause any symptoms are sometimes found.

Gallbladder cancer causes

The exact cause of gallbladder cancer isn’t known, but certain things are thought to increase your chances of developing it. Researchers have found several risk factors that make a person more likely to develop gallbladder cancer. Scientists are also beginning to understand how some of these risk factors might lead to gallbladder cancer.

Chronic gallbladder inflammation is a common link among many of the risk factors for gallbladder cancer. For example, when someone has gallstones, the gallbladder may release bile more slowly. This means that cells in the gallbladder are exposed to the chemicals in bile for longer than usual. This could lead to irritation and inflammation.

In another example, abnormalities in the ducts that carry fluids from the gallbladder and pancreas to the small intestine might allow juices from the pancreas to flow backward (reflux) into the gallbladder and bile ducts. This reflux of pancreatic juices might inflame and stimulate growth of the cells lining the gallbladder and bile ducts, which might increase the risk of gallbladder cancer.

Scientists are starting to understand how risk factors such as inflammation might lead to certain changes in the DNA of cells, making them grow abnormally and form cancers. DNA is the chemical in each of your cells that makes up your genes (the instructions for how your cells function). You usually look like your parents because they are the source of your DNA. But DNA affects more than how you look.

- Some genes control when cells grow, divide into new cells, and die. Genes that help cells grow, divide, and stay alive are called oncogenes.

- Genes that slow down cell division or cause cells to die at the right time are called tumor suppressor genes.

Cancers can be caused by DNA changes (mutations) that turn on oncogenes or turn off tumor suppressor genes. Changes in several different genes are usually needed for a cell to become cancerous.

Some people inherit DNA mutations from their parents that greatly increase their risk for certain cancers. But inherited gene mutations are not thought to cause very many gallbladder cancers.

Gene mutations related to gallbladder cancers are usually acquired during life rather than being inherited. For example, acquired changes in the TP53 tumor suppressor gene are found in many cases of gallbladder cancer. Other genes that may play a role in gallbladder cancers include KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA. Some of the gene changes that lead to gallbladder cancer might be caused by chronic inflammation. But sometimes the cause of these changes is not known. Many gene changes might just be random events that sometimes happen inside a cell, without having an outside cause.

Risk Factors for Gallbladder Cancer

A risk factor is anything that affects your chance of getting a disease such as cancer. Different cancers have different risk factors. Some risk factors, like smoking, can be changed. Others, like a person’s age or family history, can’t be changed. But having a risk factor, or even several risk factors, does not mean that a person will get the disease. And many people who get the disease may have few or no known risk factors.

Scientists have found several risk factors that make a person more likely to develop gallbladder cancer. Many of these are related in some way to chronic inflammation (irritation and swelling) in the gallbladder.

Factors that can increase the risk of gallbladder cancer include:

- Your sex. Gallbladder cancer is more common in women.

- Your age. Your risk of gallbladder cancer increases as you age.

- A history of gallstones. Gallbladder cancer is most common in people who have gallstones or have had gallstones in the past. Larger gallstones may carry a larger risk. Still, gallstones are very common and even in people with this condition, gallbladder cancer is very rare.

- Other gallbladder diseases and conditions. Other gallbladder conditions that can increase the risk of gallbladder cancer include polyps, chronic inflammation and infection.

- Inflammation of the bile ducts. Primary sclerosing cholangitis, which causes inflammation of the ducts that drain bile from the gallbladder and liver, increases the risk of gallbladder cancer.

Gallstones

Gallstones are the most common risk factor for gallbladder cancer. Gallstones are pebble-like collections of cholesterol and other substances that form in the gallbladder and can cause chronic inflammation. Up to 4 out of 5 people with gallbladder cancer have gallstones when they’re diagnosed. But gallstones are very common, and gallbladder cancer is quite rare, especially in the United States. And most people with gallstones never develop gallbladder cancer.

Porcelain gallbladder

Porcelain gallbladder is a condition in which the wall of the gallbladder becomes covered with calcium deposits. It sometimes occurs after long-term inflammation of the gallbladder (cholecystitis), which can be caused by gallstones. People with this condition have a higher risk of developing gallbladder cancer, possibly because both conditions can be related to inflammation.

Female gender

In the United States, gallbladder cancer occurs 3 to 4 times more often in women than in men. Gallstones and gallbladder inflammation are important risk factors for gallbladder cancer and are also much more common in women than men.

Obesity

Patients with gallbladder cancer are more often overweight or obese than people without this disease. Being overweight causes changes in hormones in the body, particularly for women. It could be this change in the body’s hormone balance that increases the risk of gallbladder cancer. Obesity is also a risk factor for gallstones, which might help explain this link.

Diabetes

You might have an increased risk of gallbladder cancer or cancer of the bile duct if you have diabetes.

Older age

Gallbladder cancer is seen mainly in older people, but younger people can develop it as well. The average age of people when they are diagnosed is 72. Most people with gallbladder cancer are 65 or older when it’s found.

Ethnicity and geography

In the United States, the risk of developing gallbladder cancer is highest among Mexican Americans and Native Americans. They are also more likely to have gallstones than members of other ethnic and racial groups. The risk is lowest among African Americans. Worldwide, gallbladder cancer is much more common in India, Pakistan, and Central European and South American countries than it is in the United States.

Areas of the world where gallbladder cancer is significantly high are:

- Latin America

- Asia

- Eastern and Central Europe

Low rates of gallbladder cancer are found in:

- western countries such as UK, USA, Australia, Canada and New Zealand

- western and Mediterranean European countries

Choledochal cysts

Choledochal cysts are bile-filled sacs that are connected to the common bile duct, the tube that carries bile from the liver and gallbladder to the small intestine. Choledochal means having to do with the common bile duct. The cysts can grow large over time and may contain as much as 1 to 2 quarts of bile. The cells lining the sac often have areas of pre-cancerous changes, which increase a person’s risk for gallbladder cancer.

Abnormalities of the bile ducts

The pancreas is another organ that releases fluids through a duct into the small intestine to help digestion. This duct normally meets up with the common bile duct just as it enters the small intestine. Some people have a defect where these ducts meet that lets juice from the pancreas flow backward (reflux) into the bile ducts. This backward flow also keeps bile from flowing out of the bile ducts as quickly as it should. People with these abnormalities are at higher risk of gallbladder cancer. Scientists are not sure if the increased risk is due to damage caused by the pancreatic juice or is due to the bile that can’t quickly flow through the ducts causing them to be damaged by substances in the bile itself.

Gallbladder polyps

A gallbladder polyp is a growth that bulges from the surface of the inner gallbladder wall. Some polyps are formed by cholesterol deposits in the gallbladder wall. Others may be small tumors (either cancer or not cancer) or may be caused by inflammation. Polyps larger than 1 centimeter (almost a half inch) are more likely to be cancer, so doctors often recommend removing the gallbladder in patients with gallbladder polyps that size or larger.

Gallstones and gallbladder inflammation

Gallstones and inflammation of the gallbladder (cholecystitis) are the most common risk factors for gallbladder cancer.

Gallstones are hard lumps, like little rocks, that form in the gallbladder. They are mostly cholesterol, mixed with other substances found in bile. About 6 to 8 out of 10 people with gallbladder cancer (60% to 80%) have gallstones or an inflamed gallbladder when they are diagnosed.

One study has shown that a family history of gallstones doubles the risk of gallbladder cancer, and that people with a family history of gallstones who also have gallstones themselves have almost 60 times the normal risk of gallbladder cancer.

Gallstones are very common but gallbladder cancer is very rare. Most people with an inflamed gallbladder or gallstones do not get gallbladder cancer.

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis is a condition in which inflammation of the bile ducts (cholangitis) leads to the formation of scar tissue (sclerosis). People with primary sclerosing cholangitis have an increased risk of gallbladder and bile duct cancer. The cause of the inflammation is not usually known. Many people with primary sclerosing cholangitis also have ulcerative colitis, a type of inflammatory bowel disease.

Industrial and environmental chemicals

It is not clear if exposure to certain chemicals in the workplace or the environment increases the risk of gallbladder cancer. This is hard to study because this cancer is not common. Some studies in lab animals have suggested that chemical compounds called nitrosamines may increase the risk of gallbladder cancer. Other studies have found that gallbladder cancer might occur more in workers in the rubber and textile industries than in the general public. More research is needed in this area to confirm or refute these possible links.

Typhoid

People chronically infected with salmonella (the bacterium that causes typhoid) and those who are carriers of typhoid are more likely to get gallbladder cancer than those not infected. This is probably because the infection can cause gallbladder inflammation. Typhoid is very rare in the United States.

A few small studies show that Helicobacter pylori bacteria might also increase the risk of gallbladder cancer. More research needs to be done to confirm this link.

Family history

Most gallbladder cancers are not found in people with a family history of the disease. A history of gallbladder cancer in the family seems to increase a person’s chances of developing this cancer, but the risk is still low because this is a rare disease.

People are 5 times more likely to develop gallbladder cancer if they have one of the following:

- any family history of gallstone disease

- a first degree relative (a parent, sibling or child) with gallbladder cancer

Because gallbladder cancer is so rare, this is still a very small risk.

Smoking

People who smoke increase their risk of gallbladder cancer by nearly 5 times (20%).

Alcohol

Drinking alcohol can increase your risk of gallbladder cancer. Heavy drinkers are more at risk of developing gallbladder than moderate drinkers. And the less you drink, the lower your risk of gallbladder cancer.

Number of children (parity)

For women the risk of gallbladder cancer increases with each child they have. Because gallbladder cancer is rare this is still a small risk.

Ionizing radiation

Ionizing radiation is a type of radiation used by some medical scans, such as x-rays and CT scans. These scans are important to help diagnose many illnesses, including cancer.

Ionizing radiation increases your risk of gallbladder cancer. Remember, the risk is still very small because this is a rare cancer.

The risks of radiation from medical scans are very low. Your doctors and dentist will keep your exposure to radiation as low as possible. They will only do x-rays and CT scans when they are necessary.

Gallbladder cancer prevention

There’s no known way to prevent most gallbladder cancers. Many of the known risk factors for gallbladder cancer, such as age, gender, ethnicity, and bile duct defects, are beyond your control. But there are things you can do that might help lower your risk.

Taking these steps helps maintain good health and may reduce a person’s risk of gallbladder cancer, as well as many other types of cancer:

- Get to and stay at a healthy weight

- Keep physically active and limit the time you spend sitting or lying down

- Follow a healthy eating pattern that includes plenty of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, and limits or avoids red and processed meats, sugary drinks, and highly processed foods

- It’s best not to drink alcohol. If you do drink, have no more than 1 drink per day for women or 2 per day for men

If you’re at a high risk of gallbladder cancer

Talk to your doctor if you think you are at higher than average risk of gallbladder cancer.

You may be able to have:

- regular checkups

- endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) test. An endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) uses a dye to highlight the bile ducts and pancreatic duct on X-ray images. A thin, flexible tube (endoscope) with a camera on the end is passed down your throat and into your small intestine. The dye enters the ducts through a small hollow tube (catheter) passed through the endoscope. Your doctor might use an endoscopic retrograde cholangio pancreatography (ERCP) to check whether there is a growth or any abnormal looking area in your gallbladder. They can also look at the inside of your small bowel (duodenum) and take tissue samples (biopsies). This test can also show a narrowing or blockage of the bile duct or pancreatic duct. So it can also help with planning surgery.

- endoscopic ultrasound

It’s important to see the doctor if you develop any gallbladder cancer symptoms. This is the best way to find gallbladder cancer at the earliest stage, when it’s most treatable.

Since gallstones are a major risk factor, removing the gallbladders of all people with gallstones might prevent many of these cancers. But gallstones are very common, and gallbladder cancer is quite rare, even in people with gallstones. Most doctors don’t recommend people with gallstones have their gallbladder removed unless the stones are causing problems. This is because, in most cases, the possible risks and complications of surgery probably don’t outweigh the possible benefit. Still, some doctors might advise removing the gallbladder if long-standing gallstone disease has resulted in a porcelain gallbladder.

Figure 5. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)

Gallbladder cancer diagnosis

Some gallbladder cancers are found after the gallbladder has been removed to treat gallstones or chronic (long-term) inflammation. Gallbladders removed for those reasons are always looked at under a microscope to see if they contain cancer cells.

Most gallbladder cancers, though, are not found until a person goes to a doctor because they have symptoms.

Medical history and physical exam

If you have any signs or symptoms that suggest you might have gallbladder cancer, your doctor will want to take a complete medical history to check for risk factors and to learn more about your symptoms.

Your doctor will examine you to look for signs of gallbladder cancer and other health problems. The exam will focus mostly on the abdomen (belly) to check for any lumps, tenderness, or fluid build-up. The skin and the white part of the eyes will be checked for jaundice (a yellowish color). Sometimes, cancer of the gallbladder spreads to lymph nodes, causing a lump that can be felt beneath the skin. Lymph nodes above the collarbone and in several other locations may be checked.

If symptoms and/or the physical exam suggest you might have gallbladder cancer, tests will be done. These might include lab tests, imaging tests, and other procedures.

Tests and procedures used to diagnose gallbladder cancer include:

- Blood tests. Blood tests to evaluate your liver function may help your doctor determine what’s causing your signs and symptoms.

- Imaging of the gallbladder. Imaging tests that can create pictures of the gallbladder include ultrasound, computerized tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Blood tests

Blood tests can:

- check your general health, including how well your liver and kidneys are working

- check numbers of blood cells

- help diagnose cancer and other conditions

Your blood sample is sent to the laboratory. A blood doctor can look at your sample under a microscope.

They can see the different types of cells and can count the different blood cells. They can also test for different kinds of chemicals and proteins in the blood.

Tests of liver and gallbladder function

Your doctor may order lab tests to find out how much bilirubin is in the blood. Bilirubin is the chemical that gives the bile its yellow color. Problems in the gallbladder, bile ducts, or liver can raise the blood level of bilirubin. A high bilirubin level tells the doctor that there may be gallbladder, bile duct, or liver problems.

Your doctor may also do tests for albumin, liver enzymes (alkaline phosphatase [ALP], aspartate aminotransferase [AST], alanine aminotransferase [ALT], and gamma-glutamyl transferase [GGT]), and certain other substances in your blood. These may be called liver function tests. They can help diagnose liver, bile duct, or gallbladder disease.

Tumor markers

Tumor markers are substances made by cancer cells that can sometimes be found in the blood, urine or body tissues. People with gallbladder cancer may have high blood levels of the markers called CEA and CA 19-9. Usually the blood levels of these markers are high only when the cancer is in an advanced stage. These markers are not specific for gallbladder cancer – that is, other cancers or even some other health conditions also can make them go up.

These tests can sometimes be useful after a person is diagnosed with gallbladder cancer. If the levels of these markers are found to be high, they can be followed over time to help tell how well treatment is working.

Imaging tests

Imaging tests use x-rays, magnetic fields, or sound waves to create pictures of the inside of your body. Imaging tests can be done for a number of reasons, including:

- To look for suspicious areas that might be cancer

- To help a doctor guide a biopsy needle into a suspicious area to take a sample

- To learn how far cancer has spread

- To help guide certain types of treatments

- To help determine if treatment is working

- To look for signs of the cancer coming back after treatment

People who have (or might have) gallbladder cancer may have one or more of the following tests.

Ultrasound

For this test, a small instrument called a transducer gives off sound waves and picks up their echoes as they bounce off organs inside the body. The echoes are converted by a computer into an image on a screen. The patterns of echoes can help find tumors and show how far they have grown into nearby areas.

- Abdominal ultrasound: This is often the first imaging test done in people who have symptoms like jaundice or pain in the right upper part of their abdomen (belly). This is an easy test to have and it doesn’t use radiation. You simply lie on a table while a technician moves the transducer on the skin over the right upper abdomen. Usually, the skin is first lubricated with gel. Abdominal ultrasound can also be used to guide a needle into a suspicious area or lymph node so that cells can be removed (biopsied) and looked at under a microscope. This is known as an ultrasound-guided needle biopsy.

- Endoscopic or laparoscopic ultrasound: In these techniques, the doctor puts the ultrasound transducer inside the body and closer to the gallbladder. This gives more detailed images than a standard ultrasound. The transducer is on the end of a thin, lighted tube that has a camera on it. The tube is either passed through the mouth, down through the stomach, and near the gallbladder (endoscopic ultrasound) or through a small surgical cut on your belly (laparoscopic ultrasound). If there’s a tumor, ultrasound might help the doctor see if and how far it has spread into the gallbladder wall, which helps in planning for surgery. Ultrasound may be able to show if nearby lymph nodes are enlarged, which can be a sign that cancer has reached them.

Computed tomography (CT) scan

The CT scan uses x-rays to make detailed cross-sectional images of your body. Instead of taking one picture, like a regular x-ray, a CT scanner takes many pictures as it rotates around you while you lie on a table. A computer then combines these into images of slices of the part of your body that is being studied.

A CT scanner has been described as a large donut, with a narrow table that slides in and out of the middle opening. You will need to lie still on the table while the scan is being done. CT scans take longer than regular x-rays, and you might feel a bit confined by the ring while the pictures are being taken.

Before any pictures are taken, you might be asked to drink 1 to 2 pints of a liquid called oral contrast. This helps outline the intestine so that certain areas are not mistaken for tumors. You might also need an IV (intravenous) line through which a different kind of contrast dye (IV contrast) is injected. This helps better outline structures throughout your body.

The injection can cause some flushing (redness and warm feeling). Some people are allergic and get hives or, rarely, more serious reactions like trouble breathing and low blood pressure. Be sure to tell the doctor if you have any allergies or have ever had a reaction to any contrast material used for x-rays.

CT scans can have several uses for gallbladder cancer:

- They are often used to help diagnose gallbladder cancer by showing tumors in the area.

- They can help stage the cancer (find out how far it has spread). CT scans can show the organs near the gallbladder (especially the liver), as well as lymph nodes and distant organs the cancer might have spread to.

- A type of CT known as CT angiography can be used to look at the blood vessels near the gallbladder. This can help determine if surgery is a treatment option.

- Guide a biopsy needle into a suspected tumor. This is called a CT-guided needle biopsy. To do it, you stay on the CT scanning table while the doctor advances a biopsy needle through your skin and toward the mass. CT scans are repeated until the needle is inside the mass. A small amount of tissue (a sample) is then taken out through the needle.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan

Like CT scans, MRI scans provide detailed images of soft tissues in the body. But MRI scans use radio waves and strong magnets instead of x-rays. A contrast material called gadolinium may be injected into a vein before the scan to see details better.

MRI scans provide a great deal of detail and can be very helpful in looking at the gallbladder and nearby bile ducts and other organs. Sometimes they can help tell a benign (non-cancer) tumor from one that’s cancer.

Special types of MRI scans can also be used in people who may have gallbladder cancer:

- MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), which can be used to look at the bile ducts, is described below in the section on cholangiography.

- MR angiography (MRA), which looks at blood vessels, is mentioned below in the next section on angiography.

MRI scans can be a little more uncomfortable than CT scans. They take longer, often up to an hour. You may have to lie inside a narrow tube, which is confining and can upset people who have a fear of enclosed spaces. Special, more open MRI machines can sometimes be used instead. The MRI machine also makes buzzing and clicking noises that might be disturbing. Some places will provide earplugs to help block this noise out.

Cholangiography

A cholangiogram is an imaging test that looks at the bile ducts to see if they are blocked, narrowed, or dilated (widened). This can help show if someone might have a tumor that’s blocking a duct. It can also be used to help plan surgery. There are several types of cholangiograms, each of which has different pros and cons.

- Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP): This is a non-invasive way to take images of the bile ducts using the same type of machine used for standard MRIs. Neither an endoscope or an IV contrast material is used, unlike other types of cholangiograms. Because it’s non-invasive (nothing is put in your body), doctors often use MRCP if they just need images of the bile ducts. MRCP test can’t be used to get biopsy samples of tumors or to place stents (small tubes) in the ducts to keep them open.

- Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): In this procedure, a doctor passes a long, flexible tube (endoscope) down your throat, through your stomach, and into the first part of the small intestine. This is usually done while you are sedated (given medicine to make you sleepy). A small catheter (tube) is passed out of the end of the endoscope and into the common bile duct. A small amount of contrast dye is injected through the catheter. The dye helps outline the bile ducts and pancreatic duct as x-rays are taken. The images can show narrowing or blockage of these ducts. This test is more invasive than MRCP, but it has the advantage of allowing the doctor to take samples of cells or fluid for testing. ERCP can also be used to put a stent (a small tube) into a duct to help keep it open.

- Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTC): To do this procedure, the doctor puts a thin, hollow needle through the skin of your belly and into a bile duct inside the liver. You will get medicine through an IV line to make you sleepy before the test. A local anesthetic is also used to numb the area before putting the needle. A contrast dye is then injected through the needle, and x-rays are taken as it passes through the bile ducts. Like ERCP, this test can also be used to take samples of fluid or tissues or to put a stent (small tube) into a duct to help keep it open. Because it’s more invasive, PTC is not usually used unless ERCP has already been tried or can’t be done for some reason.

Angiography

Angiography or an angiogram is an x-ray test used to look at blood vessels. A thin plastic tube called a catheter is threaded into an artery and a small amount of contrast dye is injected to outline blood vessels. Then x-rays are taken. The images show if blood flow in an area is blocked anywhere or affected by a tumor, as well as any abnormal blood vessels in the area. The test can also show if a gallbladder cancer has grown through the walls of certain blood vessels. This information is mainly used to help surgeons decide whether a cancer can be removed and to help plan the operation.

Angiography can also be done with a CT scan (CT angiography) or an MRI (MR angiography). These tend to be used more often because they give information about the blood vessels without the need for a catheter. You may still need an IV line so that a contrast dye can be injected into the bloodstream during the imaging.

Laparoscopy

Laparoscopy is a type of surgery. The doctor puts a thin tube with a light and a small video camera on the end (a laparoscope) into a small incision (cut) in the front of your abdomen (belly) to look at the gallbladder, liver, and other nearby organs and tissues. Sometimes more than one cut is made. This is usually done in the operating room while drugs are used to put you into a deep sleep and not feel pain (general anesthesia) during the surgery.

Laparoscopy can help doctors plan surgery or other treatments, and can help determine the stage (extent) of the cancer. If needed, doctors can also put special instruments in through the incisions to take out biopsy samples for testing.

Laparoscopy is often used to take out your gallbladder. This operation is called a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. If gallbladder cancer is found or suspected during that operation, surgeons usually change to an open cholecystectomy (removal of the gallbladder through a larger cut in the abdomen). The open method lets the surgeon see more and may lower the chance of releasing cancer cells into the abdomen when the gallbladder is removed. The use of the open procedure depends on the size of the cancer and whether surgery can remove it all.

Biopsy

During a biopsy, the doctor removes a tissue sample to be looked at with a microscope to see if cancer (or some other disease) is present. For most types of cancer, a biopsy is needed to make a diagnosis. Biopsies are also used to help find out how far the cancer has spread. This is important when choosing the best treatment plan.

But a biopsy isn’t always done before surgery to remove a gallbladder tumor. Doctors are often concerned that sticking a needle into the tumor or otherwise disturbing it without completely removing it might allow cancer cells to spread.

If imaging tests show a tumor in the gallbladder and there are no clear signs that it has spread, the doctor may decide to proceed directly to surgery and treat the tumor as a gallbladder cancer. In this case, the gallbladder is checked for cancer after it’s been removed.

In other cases, a doctor may feel that a biopsy of a suspicious area in the gallbladder is the best way to know for sure if it’s cancer. For example, imaging tests may show that a tumor has spread or grown too large to be removed completely by surgery. Many gallbladder cancers are not removable by the time they’re first found.

Types of biopsies

There are several ways to take biopsy samples of the gallbladder.

- During cholangiography: If ERCP or PTC is being done, a sample of bile may be collected during the procedure to look for cancer cells in the fluid.

- During laparoscopy: As noted earlier, biopsy samples can be taken during laparoscopy. Laparoscopy lets the doctor see the surface of the gallbladder and nearby areas and then take small pieces of tissue from any suspicious areas.

- Needle biopsy: If the cancer is too big or has spread to much to be removed with surgery, a needle biopsy may be done to confirm the diagnosis and help guide treatment. For this test, a thin, hollow needle is put in through the skin and into the tumor without making a cut in the skin. (The skin is numbed first with a local anesthetic.) The needle is usually guided into place using ultrasound or CT scans. When the images show that the needle is in the tumor, cells and/or fluid are drawn into the needle and sent to the lab to be tested.

In most cases, biopsy is done as a fine needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy, which uses a very thin needle attached to a syringe to suck out (aspirate) a sample of cells.Sometimes, the FNA doesn’t get enough cells for a definite diagnosis, so a core needle biopsy, which uses a slightly larger needle to get a bigger sample, may be done.

Gallbladder cancer stage

Once your doctor diagnoses your gallbladder cancer, he or she works to find if it has spread, and if so, how far. This process is called staging of your cancer. The stage of a cancer describes how much cancer is in the body. Your gallbladder cancer’s stage helps determine how serious the cancer is and how best to treat it. Doctors also use your gallbladder cancer’s stage when talking about survival statistics or your prognosis.

Doctors can use the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system or a number system to give gallbladder cancers a stage. This can seem confusing. But your doctor can help you to understand the stage of your cancer and your treatment options.

TNM stands for tumor, node and metastasis:

- T describes how deeply the tumor has grown into the gallbladder

- N describes whether there is cancer in the lymph nodes

- M stands for metastasis, which describes whether the cancer has spread (metastasize) to any other part of the body

There are four main stages in the number system, numbered 1 to 4. Some doctors also refer to stage 0. The earliest stage gallbladder cancers are called stage 0 (a very early cancer called carcinoma in situ), and then range from stages I (1) through IV (4). As a rule, the lower the number, the less the cancer has spread. A higher number, such as stage IV, means cancer has spread more. And within a stage, an earlier letter means a lower stage. Although each person’s cancer experience is unique, cancers with similar stages tend to have a similar outlook and are often treated in much the same way.

Nearly all gallbladder cancers start in the epithelium (the inside wall of the gallbladder). Over time they grow through the various layers toward the outside of the gallbladder. They may also grow to fill some or all the space inside the gallbladder at the same time.

TNM stages

The staging system most often used for gallbladder cancer is the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system, which is based on 3 key pieces of information 6:

- The extent (size) of the tumor (T): How far has the cancer grown into the wall of the gallbladder? Has the cancer grown through the gallbladder wall into nearby organs such as the liver?

- The gallbladder wall has several layers (see Figure 6). From the inside out, these are:

- The epithelium, a thin sheet of cells that line the inside wall of the gallbladder. The columnar cells of the lining epithelium concentrate the bile by absorbing some of its water and ions.

- The lamina propria, a thin layer of loose connective tissue (the epithelium plus the lamina propria form the mucosa)

- The muscularis, a layer of muscular tissue that helps the gallbladder contract, squirting its bile into the bile duct

- The perimuscular (around the muscle) fibrous tissue, another layer of connective tissue

- The serosa, the outer covering of the gallbladder that comes from the peritoneum, which is the lining of the abdominal cavity

- The depth that a tumor grows from the inside (epithelium layer) through the other outer layers (all the way through the serosa) is a key part of staging.

- The gallbladder wall has several layers (see Figure 6). From the inside out, these are:

- The spread to nearby lymph nodes (N): Has the cancer spread to nearby lymph nodes and if so, how many?

- The spread (metastasis) to distant sites (M): Has the cancer spread to distant organs such as the liver, peritoneum (the lining of the abdominal cavity) or the lungs?

The system described below is the most recent American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM system effective January 2018. This system is used to stage cancers of the gallbladder as well as cancers that start in the cystic duct (the tube that carries bile away from the gallbladder).

The gallbladder cancer TNM staging system uses the pathologic stage (also called the surgical stage) which is determined by examining the tissue removed during an operation. Sometimes, if surgery can’t be done right away or at all, the cancer will be given a clinical stage instead. This is based on the results of a physical exam, biopsy, and imaging tests. The clinical stage will be used to help plan treatment. Sometimes, though, the cancer has spread further than the clinical stage estimates, and may not predict the patient’s outlook as accurately as a pathologic stage.

Numbers or letters after T, N, and M provide more details about each of these factors. Higher numbers mean the cancer is more advanced.

Once a person’s T, N, and M categories have been determined, this information is combined in a process called stage grouping to assign an overall stage.

Cancer staging can be complex, so ask your doctor to explain it to you in a way you understand.

Figure 6. Gallbladder wall layers

Table 1. Gallbladder Cancer TNM Staging

| American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Stage | Stage grouping | Stage description* |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Tis N0 M0 | Cancer cells are only found in the epithelium (the inner layer of the gallbladder) and have not grown into deeper layers of the gallbladder. This is also known as carcinoma in situ (Tis). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 1 | T1 N0 M0 | The tumor has grown into the lamina propria or the muscle layer (muscularis) (T1). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 2A | T2a N0 M0 | The cancer has grown through the muscle layer into the fibrous tissue on the side of the peritoneum (the lining of the abdominal cavity) (T2a). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 2B | T2b N0 M0 | The cancer has grown through the muscle layer into the fibrous tissue on the side of the liver without invading the liver (T2b). It has not yet spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 3A | T3 N0 M0 | The cancer has grown through the serosa (the outermost covering of the gallbladder) and/or it has grown from the gallbladder directly into the liver and/or a nearby structure such as the stomach, duodenum (first part of the small intestine), colon, pancreas, or bile ducts outside the liver (T3). It has not yet spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or to distant sites (M0). |

| 3B | T1-3 N1 M0 | The cancer has not grown directly into the liver or nearby organs such as the stomach, duodenum, colon, pancreas or bile ducts (T1 to T3), but it has spread to no more than 3 nearby lymph nodes (N1). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

| 4A | T4 N0 or N1 M0 | The tumor has grown into one of the main blood vessels leading into the liver (portal vein or hepatic artery) or it has grown into 2 or more structures outside of the liver (T4). It has not spread to nearby lymph nodes (N0) or might have spread to no more than 3 nearby lymph nodes (N1). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

| 4B | Any T N2 M0 | The primary tumor may or may not have grown outside the gallbladder. The cancer has spread to 4 or more nearby lymph nodes (N2). It has not spread to distant sites (M0). |

| OR | ||

| Any T Any N M1 | The primary tumor may or may not have grown outside the gallbladder. The cancer may or may not have spread to nearby lymph nodes. Cancer has spread to distant sites such as the liver, peritoneum (the lining of the abdominal cavity), or the lungs (M1). | |

Footnotes: * The following additional categories are not listed on the table above:

- TX: Main tumor cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

- T0: No evidence of a primary tumor.

- NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed due to lack of information.

Number stages

There are four main stages in the number system, numbered 1 to 4. Some doctors also refer to stage 0 also known as carcinoma in situ (CIS).

Stage 0 or carcinoma in situ (CIS)

Very, very early stage gallbladder cancer is called carcinoma in situ (CIS) or stage 0. In stage 0, abnormal cells are found in the mucosa (innermost layer) of the gallbladder wall. These abnormal cells may become cancer and spread into nearby normal tissue.

Some doctors may not regard this as a true cancer because the cancer cells are just in the lining. So there is very little risk of the cancer having spread.

It is unusual for gallbladder cancer to be found this early, as there are few or no symptoms at this stage. Sometimes it can be picked up this early when someone has their gallbladder removed for gallstones.

Stage 1 gallbladder cancer

This is the earliest stage of invasive gallbladder cancer. In stage 1 gallbladder cancer, the cancer has formed in the mucosa (innermost layer) of the gallbladder wall and may have spread to the muscle layer of the gallbladder wall. The cancer has not spread to nearby tissues, lymph nodes or other organs. Stage 1 is the same as T1, N0, M0 in the TNM stages.

Stage 2 gallbladder cancer

Stage 2 gallbladder cancer means that cancer has grown through the muscle layer of the gallbladder wall and into the connective tissue underneath. It has not spread outside the gallbladder. Stage 2 in the TNM stages is the same as T2, N0, M0.

Stage 2 gallbladder cancer is divided into stages 2A and 2B, depending on where the cancer has spread in the gallbladder.

- Stage 2A gallbladder cancer means the cancer has spread through the muscle layer to the connective tissue layer of the gallbladder wall on the side of the gallbladder that is not near the liver.

- Stage 2B gallbladder cancer means the cancer has spread through the muscle layer to the connective tissue layer of the gallbladder wall on the same side as the liver. Cancer has not spread to the liver.

Stage 3 gallbladder cancer

Stage 3 gallbladder cancer is divided into 3A and 3B, depending on where the cancer has spread:

- Stage 3A gallbladder cancer means the cancer has spread through the connective tissue layer of the gallbladder wall but has not spread to the lymph nodes (this is the same as TNM stages T3, N0, M0) and one or more of the following is true:

- Cancer has spread to the serosa (layer of tissue that covers the gallbladder).

- Cancer has spread to the liver.

- Cancer has spread to one nearby organ or structure (such as the stomach, small intestine, colon, pancreas, or the bile ducts outside the liver).

- Stage 3B gallbladder cancer means the cancer has formed in the mucosa (innermost layer) of the gallbladder wall and may have spread to the muscle, connective tissue, or serosa (layer of tissue that covers the gallbladder) and may have also spread to the liver or to one nearby organ or structure (such as the stomach, small intestine, colon, pancreas, or the bile ducts outside the liver). Cancer has spread to one to three nearby lymph nodes (this is the same as T1, T2 or T3, N1 or M0).

Stage 4 gallbladder cancer

Stage 4 gallbladder cancer means that the cancer is advanced. Stage 4 gallbladder cancer is divided into stage 4A and 4B.

- Stage 4A gallbladder cancer means the cancer has either grown into one of the main blood vessels (the portal vein or hepatic artery) leading into the liver, or into 2 or more organs outside of the liver. The cancer might also have spread into one to three nearby lymph nodes. This is the same as T4, N0 or N1, M0.

- Stage 4B gallbladder cancer means the cancer may have spread to nearby organs or structures. The cancer has spread:

- to four or more nearby lymph nodes, but has not spread to distant organs in the body. This is also known as any T, N2, M0;

- OR

- to other parts of the body, such as the peritoneum and liver. This is also known as any T, any N, M1.

Other Prognostic Factors

Besides your stage, there are other factors that can affect your prognosis (outlook).

Gallbladder cancer Grade

The grade describes how closely the cancer looks like normal tissue when seen under a microscope.

The scale used for grading gallbladder cancer is from 1 to 3.

- Grade 1 (G1) means the cancer looks much like normal gallbladder tissue.

- Grade 2 (G2) falls somewhere in between.

- Grade 3 (G3) means the cancer looks very abnormal.

Low-grade cancers (G1) tend to grow and spread more slowly than high-grade (G3) cancers. Most of the time, the outlook is better for Grade 1 and Grade 2 cancers than it is for Grade 3 cancers of the same stage for gallbladder cancer.

Gallbladder cancer Subtype

The specific type of gallbladder cancer you have can influence your outlook. Rare cancer types such as squamous and adenosquamous carcinomas of the gallbladder tend to have a worse prognosis (outlook) than adenocarcinomas (the most common type) and papillary carcinomas.

Lymphovascular Invasion

If cancer cells are seen in small blood vessels (vascular) or lymph vessels (lymphatics) under the microscope, it’s called lymphovascular invasion. When cancer is growing in these vessels, there’s a greater chance that it has spread outside the gallbladder. Gallbladder cancers with lymphovascular invasion tend to have a poor prognosis.

Extent of Resection

If the entire gallbladder tumor can be removed with surgery, it can impact the overall outlook. Cancers that can be removed completely by surgery tend to have a better outlook than those that cannot.

- Resectable cancers are those that doctors believe can be removed completely by surgery.

- Unresectable cancers have spread too far or are in too difficult a place to be removed entirely by surgery.

Only a small percentage of gallbladder cancers are resectable when they’re first found.

Gallbladder cancer survival rate

Survival rates can give you an idea of what percentage of people with the same type and stage of cancer are still alive a certain amount of time (usually 5 years) after they were diagnosed. They can’t tell you how long you will live, but they may help give you a better understanding of how likely it is that your treatment will be successful.

Keep in mind that survival rates are estimates and are often based on previous outcomes of large numbers of people who had a specific cancer, but they can’t predict what will happen in any particular person’s case. These statistics can be confusing and may lead you to have more questions. Your doctor is familiar with your situation; ask how these numbers may apply to you.

A relative survival rate compares people with the same type and stage of cancer to people in the overall population. For example, if the 5-year relative survival rate for a specific stage of gallbladder cancer is 60%, it means that people who have that cancer are, on average, about 60% as likely as people who don’t have that cancer to live for at least 5 years after being diagnosed.

The numbers below come from the American College of Surgeons/American Cancer Society National Cancer Data Base as published in the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual in 2010 and are based on more than 10,000 patients diagnosed with gallbladder cancer from 1989 to 1996.

Survival rates are often based on previous outcomes of large numbers of people who had the disease, but they can’t predict what will happen with any particular person. Many other factors can also affect a person’s outlook, such as their age and overall health, and how well the cancer responds to treatment. Even when taking these other factors into account, survival rates are at best rough estimates. Your doctor can tell you how the numbers above apply to you, as he or she knows your situation best.

Table 2. Gallbladder cancer survival rate by stage

| Stage | 5-Year Survival Rate |

|---|---|

| 0 | 80.00% |

| 1 | 50.00% |

| 2 | 28.00% |

| 3A | 8.00% |

| 3B | 7.00% |

| 4A | 4.00% |

| 4B | 2.00% |

Table 3. 5-year relative survival rates for gallbladder cancer

| National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) stage | 5-year relative survival rate |

| Localized | 66.00% |

| Regional | 28.00% |

| Distant | 2.00% |

| All SEER stages combined | 19.00% |

The National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database tracks 5-year relative survival rates for gallbladder cancer in the United States, based on how far the cancer has spread. However, the SEER does not group cancers by AJCC TNM stages (stage 1, stage 2, stage 3, etc.). Instead, it groups cancers into localized, regional, and distant stages:

- Localized: There is no sign that the cancer has spread outside of the gallbladder.

- Regional: The cancer has spread outside the gallbladder to nearby structures or lymph nodes.

- Distant: The cancer has spread to distant parts of the body, such as the lungs.

Footnotes:

- These numbers are based on people diagnosed with cancers of the gallbladder between 2011 and 2017.

- These numbers apply only to the stage of the cancer when it is first diagnosed. They do not apply later on if the cancer grows, spreads, or comes back after treatment.

- These numbers don’t take everything into account. Survival rates are grouped based on how far the cancer has spread. But other factors, such as your age and overall health, and how well the cancer responds to treatment, can also affect your outlook.

- People now being diagnosed with gallbladder cancer may have a better outlook than these numbers show. Treatments improve over time, and these numbers are based on people who were diagnosed and treated at least 5 years earlier.

Gallbladder cancer prognosis

Gallbladder cancer can be cured only if it is found before it has spread, when it can be removed by surgery. The prognosis for gallbladder cancer is generally poor 2. Factors affecting gallbladder cancer prognosis is the stage of the cancer (whether the cancer has spread from the gallbladder to other places in the body) at discovery, the type and grade of gallbladder cancer (how the cancer cell looks under a microscope), the specific location of the tumor, whether the cancer can be completely removed by surgery (its operability), its response to chemotherapy, whether and where it has spread and whether the cancer has just been diagnosed or has recurred (come back) 8. Gallbladder cancer has a high recurrence rate and a poor 5-year survival rate.

Gallbladder cancer treatment

What gallbladder cancer treatment options are available to you will depend on the stage of your cancer, your overall health and your preferences.

The initial goal of treatment is to remove the gallbladder cancer, but when that isn’t possible, other therapies may help control the spread of the disease and keep you as comfortable as possible.

After gallbladder cancer is found and staged, your cancer care team will discuss your treatment options with you. The doctors on this team may include:

- A surgeon or a surgical oncologist (a surgeon who specializes in cancer treatment)

- A radiation oncologist: a doctor who uses radiation to treat cancer

- A medical oncologist: a doctor who uses chemotherapy and other medicines to treat cancer

- A gastroenterologist (GI doctor): a doctor who treats diseases of the digestive system

It’s important to discuss all of your treatment options, including their goals and possible side effects, with your doctors to help make the decision that best fits your needs. It’s also very important to ask questions if there is anything you’re not sure about.

The main types of treatments for gallbladder cancer include:

- Surgery

- Radiation therapy

- Chemotherapy

- Targeted therapy

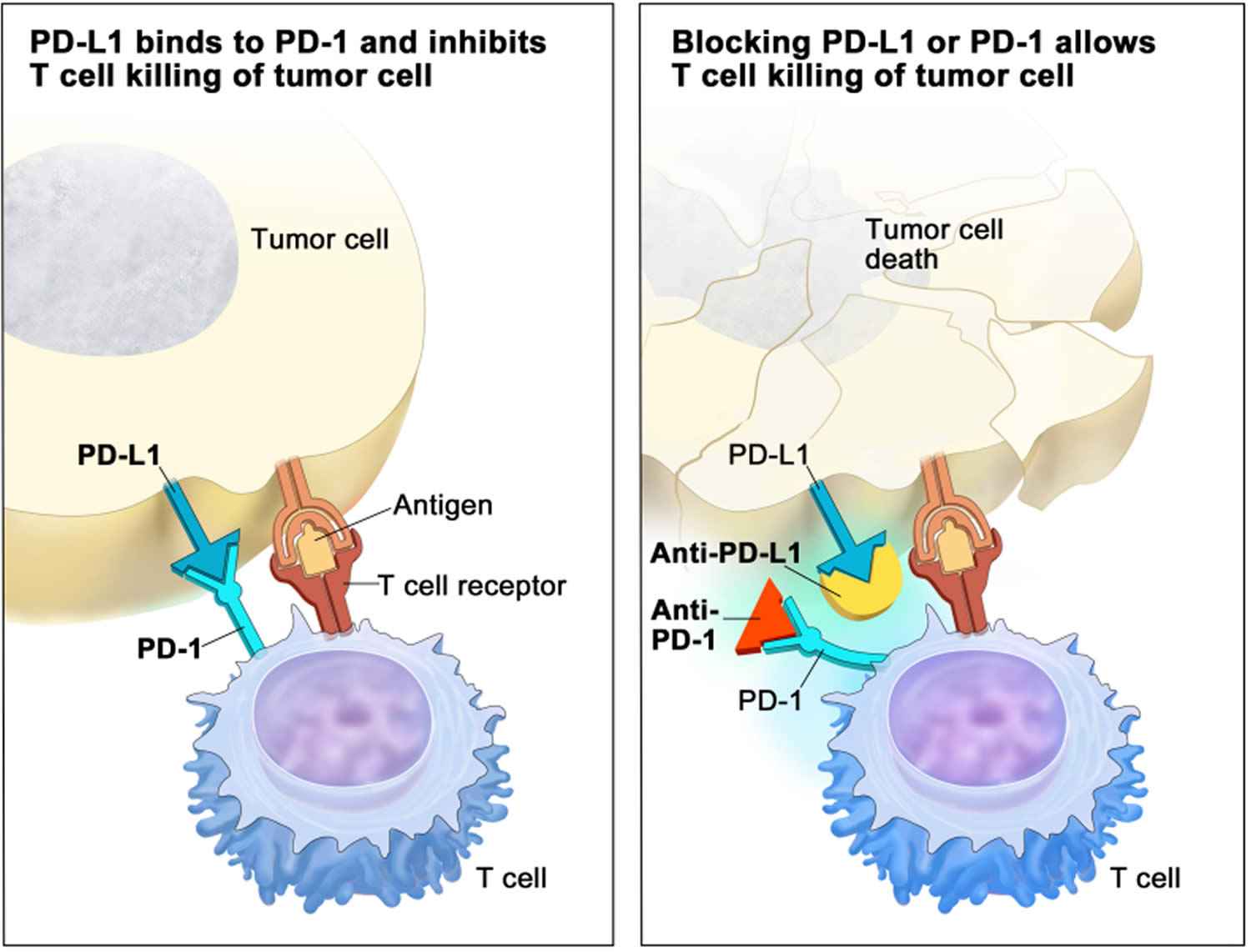

- Immunotherapy

- Palliative therapy

Your treatment plan will depend on the stage of your cancer and other factors such as your general health and your preferences.

Surgery for gallbladder cancer

Surgery is the main treatment for gallbladder cancer. There are 2 general types of surgery for gallbladder cancer: potentially curative surgery (resectable and unresectable) and palliative surgery.

- Potentially curative surgery (or resectable) is done when imaging tests or the results of earlier surgeries show there is a good chance that the surgeon can remove all of the cancer can be removed.

- Resectable describes cancers doctors believe can be removed completely. This is potentially curative surgery.

- Unresectable means doctors think the cancer is too far advanced, it has spread too far, or is in too difficult a place to be entirely removed by surgery.

- Only a small percentage of gallbladder cancers are resectable when they are first found.

- If potentially curative surgery is being considered, you may want to get a second opinion or even be referred to a large cancer center. Nearly all doctors agree that surgery offers the only realistic chance for curing people with gallbladder cancer. But there are differences of opinion about how advanced a gallbladder cancer can be and still be treatable with surgery. The surgery needed for gallbladder cancer is often complex and requires an experienced surgeon. These operations are most often done at major cancer centers.

- Palliative surgery or surgery to control symptoms is surgery done to relieve symptoms pain or treat (or even prevent) complications, such as blockage of the bile ducts. This type of surgery is done when the cancer tumor is too widespread to be removed completely. Palliative surgery is not expected to cure the cancer, but it can sometimes help a person feel better and can help them live longer.

There are a number of possible operations that can be used to remove the cancer (and gallbladder). Some of them are extremely major surgery. The type of operation you have depends on where the cancer is in the gallbladder and how far it has spread outside your gallbladder.

Possible risks and side effects of surgery

The risks and side effects of surgery depend on how much tissue is removed and your overall general health before the surgery. All surgery carries some risk, including the possibility of bleeding, blood clots, infections, complications from anesthesia, and pneumonia.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the least invasive operation and tends to have fewer side effects. Most people will have at least some pain from the incisions for a few days after the operation, but this can usually be controlled with medicines. A bigger incision is needed for an open cholecystectomy, so there is usually more pain and a longer recovery time.

Extended cholecystectomy is a major operation that might mean removing parts of several organs. This can have a major significant effect on a person’s recovery and health after the surgery. Serious problems soon after surgery can include bile leakage into the abdomen, infections, and liver failure. Because most of the organs removed are involved in digestion, eating and nutrition problems may be a concern after surgery. Your doctor or nurse will discuss the possible side effects with you in more detail before your surgery.

Laparoscopy to plan for gallbladder cancer surgery

Often, when gallbladder cancer is suspected, the surgeon will do a laparoscopy before any other surgery. This is done to help look for any spread of the cancer that could make curative surgery not an option. During the laparoscopy, the surgeon can look for areas of cancer that did not show up on imaging tests. If the cancer is resectable, laparoscopy can also help plan the operation to remove it.

Surgery to remove gallbladder cancer can have serious side effects and, depending on how extensive it is, you may need many weeks for recovery. If your cancer is very unlikely to be curable, be sure to carefully weigh the pros and cons of surgery or other treatments that will need a lot of recovery time. It’s very important to understand the goal of any surgery for gallbladder cancer, what the possible benefits and risks are, and how the surgery is likely to affect your quality of life.

Simple cholecystectomy (removal of the gallbladder)

The operation to remove the gallbladder is called a cholecystectomy. If only the gallbladder and nothing else is removed, it’s called a simple cholecystectomy. This operation is often done to remove the gallbladder for other reasons such as gallstones, but it’s not done if gallbladder cancer is known or suspected (a more extensive operation is needed done instead).

Gallbladder cancers are sometimes found by accident after a person has a cholecystectomy for another reason. If the cancer is at a very early stage (T1a) and is thought to have been removed completely, no further surgery may be needed. If there’s a chance the cancer may have spread beyond the gallbladder, more extensive surgery may be advised.

A simple cholecystectomy can be done in 2 ways:

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: This is the most common way to remove a gallbladder for anon-cancerous problem that’s not cancer. The surgeon puts a laparoscope , a thin, flexible tube with a tiny video camera on the end, into the body through a small cut in the skin of the abdomen (belly). Long surgical tools are put in through other small openings to take out remove the gallbladder. Laparoscopic surgery tends to be easier for patients because of the smaller incision size. But this type of operation isn’t used if gallbladder cancer is suspected. This surgery gives the surgeon only a limited view of the area around the gallbladder, so there’s a greater chance that some cancer might be missed and left behind. Removing the gallbladder this way might also lead to the accidental spread of the cancer as the gallbladder is taken out.

- Open cholecystectomy: The surgeon takes out the gallbladder through a large incision (cut) in the abdominal wall. This method is sometimes used for gallbladder problems that aren’t cancer (such as gallstones), and may lead to the discovery of gallbladder cancer. But if gallbladder cancer is suspected before surgery, doctors prefer to do an extended cholecystectomy.

Extended (radical) cholecystectomy

Because of the risk that the cancer will come back if just the gallbladder is removed, a more extensive operation, called an extended (or radical) cholecystectomy, is done in most cases of gallbladder cancer. This can be a complex operation, so make sure your surgeon is experienced with it.

The extent of the surgery depends on where the cancer is and how far it might have spread. At a minimum, an extended cholecystectomy removes:

- The gallbladder

- About an inch or more of liver tissue next to the gallbladder

- All of the lymph nodes in the region

If your surgeon feels it’s needed and you are healthy enough, the operation may also include removing one or more of the following:

- A larger part of the liver, ranging from a wedge-shaped section of the liver close to the gallbladder (wedge resection) to a whole lobe of the liver (hepatic lobectomy)

- The common bile duct

- Part or all of the ligament that runs between the liver and the intestines

- Lymph nodes around the pancreas and, around the major nearby blood vessels

- The pancreas

- The duodenum (the first part of the small intestine into which the bile duct drains)

- Any other areas or organs to which cancer has spread.

Surgery to remove other organs

You may also have other organs taken out during your gallbladder operation. These operations can include:

- Gastrojejunostomy. In a gastrojejunostomy, your surgeon takes out your gallbladder, bile ducts and duodenum and reconnects your stomach to your small bowel (intestine).

- Liver (hepatic) resection. Hepatic resection means taking out part of your liver. Your surgeon may do this if the cancer has spread from your gallbladder to part of your liver. It is only usually possible to do this if the cancer is small and when there are no major blood vessels affected by the cancer.

- Hepatic lobectomy. A hepatic lobectomy means removing a lobe of the liver. If you have no medical problems with your liver (such as cirrhosis) it is possible for the liver to grow back and work normally after surgery. It is important that your liver function is carefully checked before you have surgery. As the liver is such a vital organ, your doctors need to know that the remaining part of your liver can work well enough after your operation. If you have cirrhosis, your liver may not work well enough for your body to cope. Liver failure after surgery is much more likely in people who have cirrhosis.

- Hepatopancreatoduodenectomy. Hepatopancreatoduodenectomy means taking out your pancreas, duodenum and some liver tissue.

- Pancreatoduodenectomy. Pancreatoduodenectomy is also known as a Whipple’s or Kausch-Whipple’s operation. This means removing:

- part of your pancreas

- your duodenum (the first part of your small bowel)

- part of your stomach

- your gallbladder and part of your bile duct

- Large bowel resection. Large bowel resection means taking out part of the large bowel (colon). This will be done if there are signs that the cancer has spread to your large bowel. The affected part of the bowel is cut out and the two ends rejoined.

Surgery for unresectable cancers

Surgery is less likely to be done for unresectable cancers, but there are some instances where it might be helpful, this is called palliative surgery. The goal is not to treat the cancer, but to treat the problems it causes. An example is putting a plastic or expandable metal tube (called a stent) inside bile duct that’s blocked by the tumor. This can keep the duct open and allow bile to flow through it.

Radiation therapy for gallbladder cancer

Radiation therapy also known as radiotherapy uses high-energy rays (such as x-rays) or particles to destroy cancer cells. Doctors aren’t sure of the best way to use radiation therapy to treat gallbladder cancer, but it might be used in one of these ways:

- After surgery has removed the cancer: Radiation may be used to try to kill any cancer that might have been left after surgery but was too small to see. This is called adjuvant therapy.

- As part of the main therapy for some advanced cancers: Radiation therapy might be used as a main therapy for some patients whose cancer has not spread widely throughout the body, but can’t be removed with surgery. While treatment in this case does not cure the cancer, it may help patients live longer.

- As palliative therapy: Radiation therapy is used often to help relieve symptoms if the cancer is too advanced to be cured. It may be used to help relieve pain or other symptoms by shrinking tumors that block blood vessels or bile ducts, or press on nerves.

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT)

For gallbladder cancer, a large machine is used to create a beam of x-rays or particles that are aimed at the cancer. This is called external beam radiation therapy (EBRT).

Before your treatments start, the radiation team will take careful measurements to determine the correct angles for aiming the radiation beams and the proper dose of radiation. The treatment is much like getting an x-ray, but the radiation is much stronger. The procedure itself is painless. Each treatment lasts only a few minutes, but the set-up time − getting you into place for treatment − usually takes longer. Most often, radiation treatments are given 5 days a week for many weeks.

These are some of the ways external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) might be given: