What is GERD

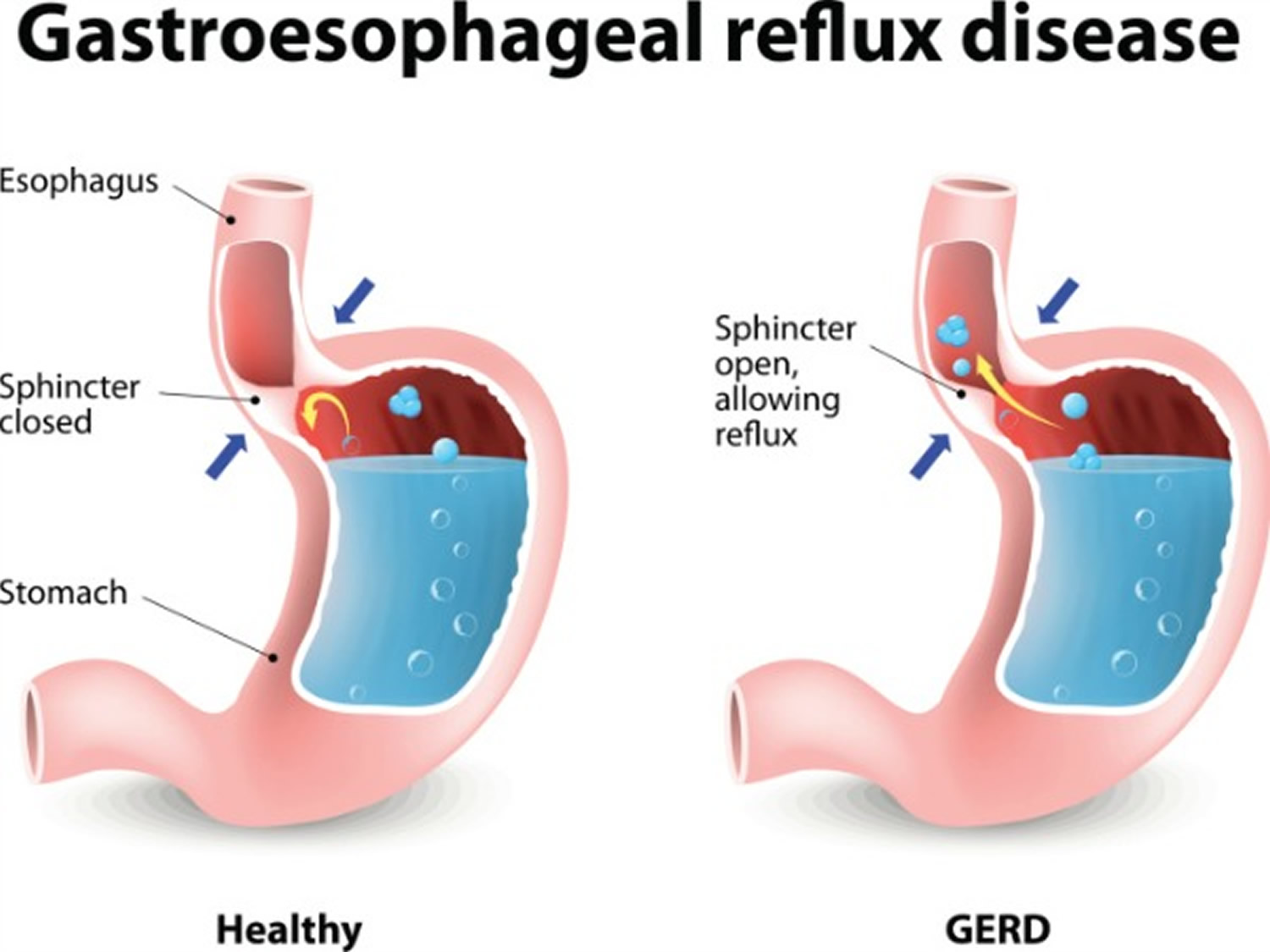

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) happens when a muscle at the end of your esophagus (lower esophageal sphincter) does not close properly (see Figures 2 and 3). This allows stomach contents (stomach acid) to leak back or reflux, into the esophagus and irritate the lining of your esophagus 1. The most common symptoms of GERD are heartburn and regurgitation. Heartburn is a burning sensation in your chest behind the breastbone caused by stomach acid traveling up towards the throat (acid reflux). Regurgitation is a feeling of fluid or food coming up into the chest. Many people experience both symptoms; however, some patients can have one without the other. Heartburn that occurs frequently and interferes with your routine is considered gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). But you can have GERD without having heartburn. People with GERD may also have nausea and belly pain. GERD can seriously damage your esophagus or lead to precancerous changes in the esophagus called Barrett’s esophagus.

Doctors also refer to GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease) as:

- acid indigestion

- acid reflux

- acid regurgitation

- heartburn

- reflux

Many people experience acid reflux from time to time, especially after a heavy meal. GERD is mild acid reflux that occurs at least twice a week, or moderate to severe acid reflux that occurs at least once a week. However, GERD is defined as frequent symptoms (two or more times a week) or when the esophagus suffers damage from reflux such as narrowing, erosions, or pre-cancerous changes 2. GERD affects about 20 percent of the U.S. population 3. However, the true prevalence of acid reflux could be higher because more individuals have access to over-the-counter acid, reducing medications 4, 5. The prevalence of GERD is slightly higher in men compared to women 6. GERD is also more common amongst the elderly, obese and pregnant women. A large meta-analysis study by Eusebi et al. 7 estimated the pooled prevalence of GERD symptoms to be marginally higher in women compared with men (16.7%) vs. 15.4%. Women presenting with acid reflux symptoms are more likely to have GERD than men who are more likely to have erosive esophagitis 8. However, men with longstanding symptoms of GERD have a higher incidence of Barrett’s esophagus (23%) compared to women (14%) 9.

GERD treatment may require prescription medications and, occasionally, surgery or other procedures. Most people can manage the discomfort of GERD with lifestyle changes and over-the-counter medications.

If you have GERD, acid reflux or heartburn, you can try these things:

- Lose weight, if you are overweight

- Stop smoking

- Eat small frequent meals rather than several large meals daily

- Raise the head of your bed by six inches if you have symptoms at night

- Avoid eating two hours before bedtime if you have symptoms at night

But some people with GERD may need stronger medications or surgery to ease symptoms. You should see a doctor if you have persistent gastroesophageal reflux symptoms that do not get better with over-the-counter medications or change in your diet.

Figure 1. Esophagus

Figure 2. Lower esophageal sphincter (LES)

Figure 3. lower esophageal sphincter (endoscopic view)

Chest pain may be a symptom of a heart attack! Seek help right away if you have severe chest pain or pressure, especially when combined with pain in the arm or jaw or difficulty breathing.

Make an appointment with your doctor if:

- Heartburn occurs more than twice a week

- Symptoms persist despite use of nonprescription medications

- You have difficulty swallowing

- You have persistent nausea or vomiting

- You have weight loss because of poor appetite or difficulty eating

See your doctor right away if you have any of the following:

- Bleeding during bowel movements or dark tarry stool

- Losing weight without trying (unexplained weight loss)

- Trouble swallowing or pain while swallowing

- Decreased appetite (loss of appetite) or feeling full sooner than usual

- Continued heartburn while taking the medicine

- Signs of bleeding in the digestive tract, such as:

- vomit that contains blood or looks like coffee grounds

- stool that contains blood or looks black and tarry

Is acid reflux, GERD and heartburn the same?

These terms are often used interchangeably, but they actually have very different meanings. GERD (gastroesophageal reflux disease) is the disease or diagnosis defined as regular symptoms caused by the flow of gastric contents into the esophagus. Heartburn is one of the symptoms of GERD. Acid reflux is the reason why patients have GERD. There is actually reflux that can be non-acidic that can be seen in GERD as well.

What can make my heartburn worse?

Many things can make heartburn worse. Heartburn is most common after overeating, when bending over or when lying down. Pregnancy, stress, and certain foods can also make heartburn worse.

Things that can make heartburn worse:

- Cigarette smoking

- Certain drinks, including coffee (both regular and decaffeinated), other drinks that contain caffeine, alcohol, and carbonated drinks

- Citrus fruits

- Tomato products

- Chocolate, mints, or peppermints

- Fatty foods or spicy foods (such as pizza, chili, and curry)

- Lying down too soon after eating

- Being overweight or obese

- Certain medicines (such as sedatives and some medicines for high blood pressure)

What food to avoid if you have GERD?

Some people who have GERD find that certain foods or drinks trigger symptoms or make symptoms worse. Avoid eating or drinking the following foods that may make acid reflux or GERD worse 10:

- acidic foods, such as citrus fruits, tomatoes and tomato products

- chocolate

- coffee and other sources of caffeine

- peppermint

- high-fat foods

- spicy foods

- alcoholic drinks

- mint

Talk with your doctor about your diet and foods or drinks that seem to increase your symptoms. Your doctor may recommend reducing or avoiding certain foods or drinks to see if GERD symptoms improve.

What can I eat if I have GERD?

Eating healthy and balanced amounts of different types of foods is good for your overall health.

If you’re overweight or obese, talk with your doctor or a dietitian about dietary changes that can help you lose weight and decrease your GERD symptoms.

Stock your kitchen with foods from these foods that help prevent acid reflux:

High-fiber foods

High-fiber foods make you feel full so you’re less likely to overeat, which may contribute to heartburn. So, load up on healthy fiber from these foods:

- Whole grains such as oatmeal, couscous and brown rice.

- Root vegetables such as sweet potatoes, carrots and beets.

- Green vegetables such as asparagus, broccoli and green beans.

Alkaline foods

Foods fall somewhere along the pH scale (an indicator of acid levels). Those that have a low pH are acidic and more likely to cause reflux. Those with higher pH are alkaline and can help offset strong stomach acid.

Alkaline foods include:

- Bananas

- Melons

- Cauliflower

- Fennel

- Nuts

- Ginger is one of the best digestive aids because of its medicinal properties. It’s alkaline in nature and anti-inflammatory, which eases irritation in the digestive tract. Try sipping ginger tea when you feel heartburn coming on.

Watery foods

Eating foods that contain a lot of water can dilute and weaken stomach acid. Choose foods such as:

- Celery

- Cucumber

- Lettuce

- Watermelon

- Broth-based soups

- Herbal tea

Can acid reflux be prevented or avoided?

There are many lifestyle changes you can make to reduce or eliminate reflux, including:

- Not drinking alcohol

- Not eating too close to bedtime

- Losing weight

- Not wearing tight clothing

- Cutting back on foods known to trigger GERD, such as chocolate, caffeine, peppermints, and greasy, spicy, and acidic foods

- Eating smaller meals or avoiding overeating

Heartburn during pregnancy

Heartburn symptoms are one of the most commonly reported complaints among pregnant women, being reported by 30% to 80% of pregnant women 11. Heartburn usually starts during the first trimester and tends to worsen during the second and third trimesters. Although gestational GERD symptoms typically resolve with delivery, women may still experience reflux symptoms post-partum that require ongoing medical therapy.

Studies have shown elevated levels of the hormone progesterone accompanied by increased intra-abdominal pressures from the enlarging uterus, may lower esophageal sphincter (LES) pressure in pregnant women contributing to heartburn symptoms, according to research highlighted in the newly updated “Pregnancy in Gastrointestinal Disorders” monograph 12 by the American College of Gastroenterology 13. From the monograph, physician experts from the American College of Gastroenterology have compiled important health tips on managing heartburn symptoms, and importantly, identifying which heartburn medications are safe for use in pregnant women and those, which should be avoided.

Strategies to Ease Heartburn Symptoms during Pregnancy

According to the American College of Gastroenterology 13, pregnant women can treat and relieve their heartburn symptoms through lifestyle and dietary changes. The following tips can help reduce heartburn discomfort 14:

- Avoid eating late at night or before retiring to bed.

- Avoid eating foods that are common heartburn triggers like greasy or spicy food, chocolate, peppermint, tomato sauces, caffeine, carbonated drinks, and citrus fruits.

- Wear loose-fitting clothes. Clothes that fit tightly around your waist put pressure on your abdomen and the lower esophageal sphincter.

- Eat smaller meals. Overfilling the stomach can result in acid reflux and heartburn.

- Don’t lie down after eating. Wait at least 3 hours after eating before going to bed. When you lie down, it’s easier for stomach contents (including acid) to back up into the esophagus, particularly when you go to bed with a full stomach.

- Raise the head of the bed 4 to 6 inches. This can help reduce acid reflux by decreasing the amount of gastric contents that reach the lower esophagus.

- Avoid tobacco and alcohol. Abstinence from alcohol and smoking can help reduce reflux symptoms and avoid fetal exposure to potentially harmful substances.

The Do’s and Don’ts of Using Heartburn Drugs during Pregnancy

Pregnant women with mild reflux usually do well with simple lifestyle changes. If lifestyle and dietary changes are not enough, you should consult your doctor before taking any medication to relieve heartburn symptoms.

According to American College of Gastroenterology President Amy E. Foxx-Orenstein, DO, FACG, “Heartburn medications to treat acid reflux during pregnancy should be balanced to alleviate the mother’s symptoms of heartburn, while protecting the developing fetus” 14. Based on a review of published scientific clinical studies (in animals and humans) on the safety of heartburn medications during pregnancy, researchers conclude there are certain drugs that are considered safe for use in pregnancy and those which should be avoided.

Antacids are one of the most common over-the-counter medications to treat heartburn. As with any drug, antacids should be used cautiously during pregnancy.

Antacids

- Antacids containing aluminum, calcium, or magnesium are considered safe and effective in treating the heartburn of pregnancy.

- Magnesium-containing antacids should be avoided during the last trimester of pregnancy because it could interfere with uterine contractions during labor.

- Avoid antacids containing sodium bicarbonate. Sodium bicarbonate could cause metabolic alkalosis and increase the potential of fluid overload in both the fetus and mother.

Histamine-type II (H-2) Receptor Antagonists

While limited data exists in humans on the safety of histamine-type II (H-2) receptor antagonists, ranitidine (Zantac®) is the only H-2 antagonist, which has been studied specifically during pregnancy.

In a double-blind, placebo controlled, triple crossover study, ranitidine (Zantac®) taken once or twice daily in pregnant heartburn patients not responding to antacids and lifestyle modification, was found to be more effective than placebo in reducing the symptoms of heartburn and acid regurgitation. No adverse effects on the fetus were reported 15

A study on the safety of cimetidine (Tagamet®) and ranitidine (Zantac®) suggests that pregnant women taking these drugs from the first trimester through their entire pregnancy have delivered normal babies 16

Proton Pump Inhibitors

Proton pump inhibitors should be reserved for pregnant patients with more severe heartburn symptoms and those not responding to antacids and lifestyle and dietary changes. Lansoprazole (Prevacid®) is the preferred proton pump inhibitor because of case reports of safety in pregnant women. Limited data exists about human safety during pregnancy with the newer proton pump inhibitors.

Table 1. GERD medication used in pregnancy

[Source 12 ]Table 2. GERD medication used during lactation (breastfeeding)

Footnote: Antacids and sucralfate are not concentrated in breast milk and are therefore safe during lactation. All H2 receptor antagonists are excreted in human breast milk. In 1994, the American Academy of Pediatrics classified cimetidine as compatible with breastfeeding 17. Ranitidine and famotidine are also safe during breastfeeding, but nizatidine should be avoided based on adverse effects noted in the offsprings of lactating rats receiving this drug 11. Little is known about proton pump inhibitor excretion in breast milk or infant safety in lactating women. Therefore these medications are not recommended if the mother is breastfeeding.

[Source 12 ]Complications of GERD / heartburn

Over time, chronic inflammation in your esophagus can cause:

- Esophagitis. Esophagitis is inflammation in the esophagus. Patients may be asymptomatic or can present with worsening symptoms of GERD. The degree of esophagitis is endoscopically graded using the Los Angeles esophagitis classification system, which employs the A, B, C, D grading system based on variables that include length, location, and circumferential severity of mucosal breaks in the esophagus 18. Adults who have chronic esophagitis over many years are more likely to develop precancerous changes in the esophagus.

- Narrowing of the esophagus (esophageal stricture). Damage to the lower esophagus from stomach acid causes scar tissue to form. The scar tissue narrows the food pathway, leading to problems with swallowing (dysphagia) or food impaction. The American College of Gastroenterology guidelines recommend esophageal dilation and continue proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy to prevent the need for repeated dilations 19.

- An open sore in the esophagus (esophageal ulcer). Stomach acid can wear away tissue in the esophagus, causing an open sore to form. An esophageal ulcer can bleed, cause pain and make swallowing difficult.

- Precancerous changes to the esophagus (Barrett’s esophagus). Damage from acid can cause changes in the tissue lining the lower esophagus. These changes are associated with an increased risk of esophageal cancer. People with Barrett’s esophagus may develop a rare esophageal cancer called esophageal adenocarcinoma. Barrett’s esophagus is more commonly seen in Caucasian males above 50 years, obesity, and history of smoking 20. Current guidelines recommend the performance of periodic surveillance endoscopy in patients with a diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus 21.

Other complications of GERD

With GERD you might breathe stomach acid into your lungs. The stomach acid can then irritate your throat and lungs, causing respiratory problems, such as

- Asthma — a long-lasting disease in your lungs that makes you extra sensitive to things that you’re allergic to

- Chest congestion, or extra fluid in your lungs

- A dry, long-lasting cough or a sore throat

- Hoarseness — the partial loss of your voice

- Laryngitis — the swelling of your voice box that can lead to a short-term loss of your voice

- Pneumonia — an infection in one or both of your lungs—that keeps coming back

- Wheezing — a high-pitched whistling sound when you breathe.

What causes GERD?

Gastroesophageal reflux and GERD happen when your lower esophageal sphincter becomes weak or relaxes when it shouldn’t, causing stomach contents (stomach acid) to rise up into the esophagus. The acid backup may be worse when you’re bent over or lying down. The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) is a 3-4 cm tonically contracted smooth muscle segment located at the esophagogastric junction (EGJ) and, along with the crural diaphragm forms the physiological esophagogastric junction (EGJ) barrier, which prevents the retrograde migration of acidic gastric contents into the esophagus 22. In otherwise healthy individuals, the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) maintains a high-pressure zone above intragastric pressures with transient relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter that occurs physiologically in response to a meal facilitating the passage of food into the stomach 1. Patients with symptoms of GERD may have frequent transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs) not triggered by swallowing, resulting in exceeding the intragastric pressure more than lower esophageal sphincter pressures permitting reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus 23. The exact mechanism of increased transient relaxation is unknown, but transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs) account for 48-73% of GERD symptoms 24. The lower esophageal sphincter tone and transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (TLESRs) are influenced by factors such as alcohol use, smoking, caffeine, pregnancy, certain medications like nitrates, and calcium channel blockers 23.

Normally, the acidic gastric contents that reach the esophagus are cleared by frequent esophageal peristalsis and neutralized by salivary bicarbonate 25. In a prospective study by Diener et al. 26, 21% of patients with GERD were noted to have defective esophageal peristalsis leading to decreased clearance of gastric reflux resulting in severe reflux symptoms and mucosal damage.

The lower esophageal sphincter becomes weak or relaxes due to certain things, such as:

- increased pressure on your abdomen from being overweight, obese, or pregnancy

- certain medicines, including:

- those that doctors use to treat asthma —a long-lasting disease in your lungs that makes you extra sensitive to things that you’re allergic to

- calcium channel blockers—medicines that treat high blood pressure

- antihistamines—medicines that treat allergy symptoms

- painkillers

- sedatives (e.g., benzodiazepines) — medicines that help put you to sleep or make you calmer

- antidepressants —medicines that treat depression

- smoking, or inhaling secondhand smoke

A hiatal hernia can also cause GERD 27. Hiatal hernia is a condition in which the opening in your diaphragm lets the upper part of the stomach move up into your chest, which lowers the pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter. Patti et al. 28 reported that patients with proven GERD with or without a small hiatal hernia had similar lower esophageal sphincter function abnormalities and acid clearance. However, patients with large hiatal hernias were noted to have shorter and weaker lower esophageal sphincter resulting in increased reflux episodes. It was also pointed out that the degree of esophagitis was worse in patients with large hiatal hernias 28. A study evaluating the relationship between hiatal hernia and reflux esophagitis by Ott et al. 29 demonstrated the presence of hiatal hernia in 94% of patients with reflux esophagitis.

Risk factors for GERD

Conditions that can increase your risk of GERD include:

- Obesity

- Bulging of the top of the stomach up into the diaphragm (hiatal hernia)

- Pregnancy

- Connective tissue disorders, such as scleroderma

- Delayed stomach emptying

Factors that can aggravate acid reflux include:

- Smoking

- Eating large meals or eating late at night

- Eating certain foods (triggers) such as fatty or fried foods

- Drinking certain beverages, such as alcohol or coffee

- Taking certain medications, such as aspirin.

Foods that may cause heartburn

Foods commonly known to be heartburn triggers cause the lower esophageal sphincter to relax and delay the digestive process, letting food sit in the stomach longer. Foods that are high in fat, salt or spice such as:

- Fried food

- Fast food

- Pizza

- Potato chips and other processed snacks

- Chili powder and pepper (white, black, cayenne)

- Fatty meats such as bacon and sausage

- Cheese

Other foods that can cause the same problem include:

- Tomato-based sauces

- Citrus fruits

- Chocolate

- Peppermint

- Carbonated beverages

Moderation is key since many people may not be able to or want to completely eliminate these foods. But try to avoid eating problem foods late in the evening closer to bedtime, so they’re not sitting in your stomach and then coming up your esophagus when you lay down at night. It’s also a good idea to eat small frequent meals instead of bigger, heavier meals and avoid late-night dinners and bedtime snacks.

GERD symptoms

If you have gastroesophageal reflux, you may taste food or stomach acid in the back of your mouth.

The most common symptom of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is regular heartburn, a painful, burning feeling in the middle of your chest (heartburn), behind your breastbone, and in the middle of your abdomen, usually after eating and might be worse at night. Not all adults with GERD have heartburn.

Common signs and symptoms of GERD include:

- Chest pain (after meals)

- Difficulty swallowing or painful swallowing

- Regurgitation of food or sour liquid

- Sensation of a lump in your throat

- Bad breath

- Nausea

- Respiratory problems

- Vomiting

- The wearing away of your teeth

If you have nighttime acid reflux, you might also experience:

- Chronic cough

- Laryngitis

- New or worsening asthma

- Disrupted sleep

Some symptoms of GERD come from its complications, including those that affect your lungs.

GERD Diagnosis

Your doctor might be able to diagnose GERD based on a physical examination and history of your signs and symptoms.

If your gastroesophageal reflux symptoms don’t improve, if they come back frequently, or if you have trouble swallowing, your doctor may recommend testing you for gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

To confirm a diagnosis of GERD, or to check for complications, your doctor might recommend:

- Upper endoscopy (upper GI endoscopy). An intravenous (IV) needle will be placed in your arm to provide a sedative. Sedatives help you stay relaxed and comfortable during the procedure. In some cases, the procedure can be performed without sedation. You will be given a liquid anesthetic to gargle or spray anesthetic on the back of your throat. Your doctor carefully feeds the endoscope down your esophagus and into your stomach and duodenum. A small camera mounted on the endoscope sends a video image to a monitor, allowing close examination of the lining of your upper GI (gastrointestinal) tract. The endoscope pumps air into your stomach and duodenum, making them easier to see. Test results can often be normal when reflux is present, but an endoscopy may detect inflammation of the esophagus (esophagitis) or other complications. An endoscopy can also be used to collect a sample of tissue (biopsy) to be tested for complications such as Barrett’s esophagus. A pathologist will examine the tissue under a microscope. Doctors may order an upper GI endoscopy to check for complications of GERD or problems other than GERD that may be causing your symptoms.

- Ambulatory acid (pH) probe test (esophageal pH monitoring). The most accurate procedure to detect acid reflux is esophageal pH and impedance monitoring. Esophageal pH and impedance monitoring measures the amount of acid in your esophagus while you do normal things, such as eating and sleeping.A gastroenterologist performs this procedure at a hospital or an outpatient center as a part of an upper GI endoscopy. Most often, you can stay awake during the procedure.A gastroenterologist will pass a thin tube through your nose or mouth into your stomach. The gastroenterologist will then pull the tube back into your esophagus and tape it to your cheek. The end of the tube in your esophagus measures when and how much acid comes up your esophagus. The other end of the tube attaches to a monitor outside your body that records the measurements.You will wear a monitor for the next 24 hours. You will return to the hospital or outpatient center to have the tube removed.This procedure is most useful to your doctor if you keep a diary of when, what, and how much food you eat and your GERD symptoms are after you eat. The gastroenterologist can see how your symptoms, certain foods, and certain times of day relate to one another. The procedure can also help show whether acid reflux triggers any respiratory symptoms.

- Bravo wireless esophageal pH monitoring (esophageal pH monitoring). Bravo wireless esophageal pH monitoring also measures and records the pH in your esophagus to determine if you have GERD. A doctor temporarily attaches a small capsule to the wall of your esophagus during an upper endoscopy. The capsule measures pH levels in the esophagus and transmits information to a receiver. The receiver is about the size of a pager, which you wear on your belt or waistband.You will follow your usual daily routine during monitoring, which usually lasts 48 hours. The receiver has several buttons on it that you will press to record symptoms of GERD such as heartburn. The nurse will tell you what symptoms to record. You will be asked to maintain a diary to record certain events such as when you start and stop eating and drinking, when you lie down, and when you get back up.To prepare for the test talk to your doctor about medicines you are taking. He or she will tell you whether you can eat or drink before the procedure. After about seven to ten days the capsule will fall off the esophageal lining and pass through your digestive tract.

- Esophageal manometry (esophageal motility test). Esophageal manometry measures muscle contractions in your esophagus. A gastroenterologist may order this procedure if you’re thinking about anti-reflux surgery.The gastroenterologist can perform this procedure during an office visit. A health care professional will spray a liquid anesthetic on the back of your throat or ask you to gargle a liquid anesthetic.The gastroenterologist passes a soft, thin tube through your nose and into your stomach. You swallow as the gastroenterologist pulls the tube slowly back into your esophagus. A computer measures and records the pressure of muscle contractions in different parts of your esophagus.The procedure can show if your symptoms are due to a weak sphincter muscle. A doctor can also use the procedure to diagnose other esophagus problems that might have symptoms similar to heartburn. A health care professional will give you instructions about eating, drinking, and taking your medicines after the procedure.

- X-ray of your upper digestive system (upper GI series). During the procedure, you will stand or sit in front of an x-ray machine and drink barium to coat the inner lining of your upper GI tract. The x-ray technician takes several x-rays as the barium moves through your GI tract. The upper GI series can’t show GERD in your esophagus; rather, the barium shows up on the x-ray and can find problems related to GERD, such as:

- hiatal hernias

- esophageal strictures

- ulcers

You may have bloating and nausea for a short time after the procedure. For several days afterward, you may have white or light-colored stools from the barium. A health care professional will give you instructions about eating, drinking, and taking your medicines after the procedure.

How to get rid of heartburn?

The goals of managing GERD or acid reflux are to address the resolution of symptoms and prevent complications such as esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal cancer. Treatment options include lifestyle modifications, medical management with antacids and antisecretory agents, surgical therapies, and endoluminal therapies.

Many nonprescription medications can help relieve heartburn. The options include:

- Antacids, which help neutralize stomach acid. Antacids may provide quick relief. But they can’t heal an esophagus damaged by stomach acid. You shouldn’t use antacids every day or for severe symptoms, except after discussing your antacid use with your doctor. Antacids can have side effects, such as diarrhea or constipation.

- H2 blockers, which can reduce stomach acid. H2 blockers don’t act as quickly as antacids, but they may provide longer relief. Examples include cimetidine (Tagamet HB) and famotidine (Pepcid AC). H2 blockers can help heal the esophagus, but not as well as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) can.

- Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which also can reduce stomach acid. Examples include esomeprazole (Nexium 24HR), lansoprazole (Prevacid 24HR) and omeprazole (Prilosec OTC). Doctors may prescribe PPIs for long-term GERD treatment.

If nonprescription treatments don’t work or you rely on them often, see your doctor. You may need prescription medication and further testing.

GERD treatment

Your doctor is likely to recommend that you first try lifestyle modifications and over-the-counter medications. If you don’t experience relief within a few weeks, your doctor might recommend prescription medication or surgery.

People with heartburn commonly reach for antacids, over-the-counter medications that neutralize stomach acid. But eating certain foods may also offer relief from symptoms.

GERD Diet

Diet plays a major role in controlling acid reflux symptoms and is the first line of therapy used for people with GERD. You can prevent or relieve your symptoms from gastroesophageal reflux or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) by changing your diet.

You may need to avoid certain foods and drinks that make your symptoms worse.

Foods commonly known to be heartburn triggers cause the lower esophageal sphincter to relax and delay the digestive process, letting food sit in the stomach longer. Foods that are high in fat, salt or spice such as:

- Fried food

- Fast food

- Pizza

- Potato chips and other processed snacks

- Chili powder and pepper (white, black, cayenne)

- Fatty meats such as bacon and sausage

- Cheese

Other foods that can cause the same problem include:

- Tomato-based sauces

- Citrus fruits

- Chocolate

- Peppermint

- Carbonated beverages

Moderation is key since many people may not be able to or want to completely eliminate these foods. But try to avoid eating problem foods late in the evening closer to bedtime, so they’re not sitting in your stomach and then coming up your esophagus when you lay down at night. It’s also a good idea to eat small frequent meals instead of bigger, heavier meals and avoid late-night dinners and bedtime snacks.

Stock your kitchen with foods from these foods that help prevent acid reflux:

High-fiber foods

High-fiber foods make you feel full so you’re less likely to overeat, which may contribute to heartburn. So, load up on healthy fiber from these foods:

- Whole grains such as oatmeal, couscous and brown rice.

- Root vegetables such as sweet potatoes, carrots and beets.

- Green vegetables such as asparagus, broccoli and green beans.

Alkaline foods

Foods fall somewhere along the pH scale (an indicator of acid levels). Those that have a low pH are acidic and more likely to cause reflux. Those with higher pH are alkaline and can help offset strong stomach acid.

Alkaline foods include:

- Bananas

- Melons

- Cauliflower

- Fennel

- Nuts

- Ginger is one of the best digestive aids because of its medicinal properties. It’s alkaline in nature and anti-inflammatory, which eases irritation in the digestive tract. Try sipping ginger tea when you feel heartburn coming on.

Watery foods

Eating foods that contain a lot of water can dilute and weaken stomach acid. Choose foods such as:

- Celery

- Cucumber

- Lettuce

- Watermelon

- Broth-based soups

- Herbal tea

Heartburn medicine over-the-counter

The options include:

- Antacids that neutralize stomach acid. Antacids, such as Mylanta, Rolaids and Tums, may provide quick relief. But antacids alone won’t heal an inflamed esophagus damaged by stomach acid. Overuse of some antacids can cause side effects, such as diarrhea or sometimes kidney problems.

- Medications to reduce acid production. These medications — known as H-2-receptor blockers — include cimetidine (Tagamet HB), famotidine (Pepcid AC), nizatidine (Axid AR) and ranitidine (Zantac). H-2-receptor blockers don’t act as quickly as antacids, but they provide longer relief and may decrease acid production from the stomach for up to 12 hours. Stronger versions are available by prescription.

- Medications that block acid production and heal the esophagus. These medications — known as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)— are stronger acid blockers than H-2-receptor blockers and allow time for damaged esophageal tissue to heal. Over-the-counter proton pump inhibitors include lansoprazole (Prevacid 24 HR) and omeprazole (Prilosec OTC, Zegerid OTC).

Heartburn medicine prescription

Prescription-strength treatments for GERD include:

- Prescription-strength H-2-receptor blockers. These include prescription-strength famotidine (Pepcid), nizatidine and ranitidine (Zantac). These medications are generally well-tolerated but long-term use may be associated with a slight increase in risk of vitamin B-12 deficiency and bone fractures.

- Prescription-strength proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). These include esomeprazole (Nexium), lansoprazole (Prevacid), omeprazole (Prilosec, Zegerid), pantoprazole (Protonix), rabeprazole (Aciphex) and dexlansoprazole (Dexilant). Although generally well-tolerated, these medications might cause diarrhea, headache, nausea and vitamin B-12 deficiency. Chronic use might increase the risk of hip fracture 30 and hypomagnesemia (low level of serum magnesium) 31. Research also suggests that taking PPIs may increase the chance of Clostridioides difficile (C. diff) infection 32. However, data are conflicting on the increased risk of recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection when PPIs are used during treatment. In one retrospective cohort study using Veterans Administration data 33, the risk of recurrent infection after initial treatment was increased by 42% in patients who received PPIs during the course of treatment. However, in another randomized control trial reviewing inpatient treatment of C. difficile infection, there was no increased risk of recurrence 34. Talk with your doctor about the risks and benefits of taking PPIs.

- Medication to strengthen the lower esophageal sphincter. Baclofen may ease GERD by decreasing the frequency of relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter. Side effects might include fatigue or nausea.

- Prokinetics. Prokinetics help your stomach empty faster. Prokinetics can cause problems if you mix them with other medicines, so tell your doctor about all the medicines you’re taking. Prescription prokinetics include:

- bethanechol (Urecholine)

- metoclopramide (Reglan)

- Both of these medicines have side effects, including:

- nausea

- diarrhea

- fatigue, or feeling tired

- depression

- anxiety

- delayed or abnormal physical movement

- Antibiotics. Antibiotics, including erythromycin, can help your stomach empty faster. Erythromycin has fewer side effects than prokinetics; however, it can cause diarrhea.

Surgery and other procedures

GERD can usually be controlled with medication. But if medications don’t help or you wish to avoid long-term medication use, your doctor might recommend:

- Nissen fundoplication. Fundoplication is the most common surgery for GERD. In most cases, it leads to long-term reflux control. The surgeon wraps the top of your stomach around the outside of the lower esophageal sphincter, to tighten the muscle and prevent reflux. This surgery reinforces the lower muscle in the esophagus. Fundoplication is usually done with a minimally invasive (laparoscopic) procedure. The wrapping of the top part of the stomach can be partial or complete. A surgeon performs fundoplication using a laparoscope, a thin tube with a tiny video camera. The surgeon performs the operation at a hospital. You receive general anesthesia and can leave the hospital in 1 to 3 days. Most people return to their usual daily activities in 2 to 3 weeks.

- Linx device. This surgery strengthens the muscle in the esophagus. The Linx device is a ring of tiny magnetic beads made of titanium. The surgery wraps the ring around the junction between the stomach and esophagus. The magnetic attraction of the beads is strong enough to keep the opening between the stomach and esophagus closed to refluxing acid, but weak enough to allow food to pass through. This helps keep acid from backing up into your throat. Linx device can be implanted using minimally invasive surgery.

- Bariatric surgery. If you have GERD and obesity, your doctor may recommend weight-loss surgery, also called bariatric surgery, most often gastric bypass surgery. Bariatric surgery can help you lose weight and reduce GERD symptoms.

A recent meta-analysis by Gerson et al. 35 that included data from 233 patients demonstrated that subjects who underwent Transoral Incisionless Fundoplication (TIF 2.0) procedure had improved esophageal pH, decreased need for proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and significant improvement in the quality of life at three years after TIF 2.0 procedure. Another prospective study by Testoni et al. 36 demonstrated Transoral Incisionless Fundoplication (TIF) with EsophyX (EndoGastric Solutions, Redmond, WA, United States) as an effective long-term treatment option for patients with symptomatic GERD with associated hiatal hernia less than 2 cm. A meta-analysis comparing Nissen fundoplication and magnetic sphincter augmentation that included data from 688 patients with 415 who underwent MSA and the rest who were treated with Nissen fundoplication concluded that MSA was an effective therapeutic option for GERD as short-term outcomes with magnetic sphincter augmentation appeared to be comparable to Nissen fundoplication 37.

Figure 4. GERD surgery – Nissen fundoplication

Footnote: Surgery for GERD may involve a procedure to reinforce the lower esophageal sphincter called Nissen fundoplication. In this procedure, the surgeon wraps the top of the stomach around the lower esophagus. This reinforces the lower esophageal sphincter, making it less likely that acid will back up in the esophagus.

What are the disadvantages of anti-reflux surgery?

Every surgical procedure carries certain risks. Quite a lot of people have symptoms such as flatulence (“passing wind” or “farting”) and regurgitation after having anti-reflux surgery. But these symptoms could also be caused by the disease itself, and not by the surgery 38. Surgery causes swallowing problems in some people, or makes existing swallowing problems worse. Up to 23 out of 100 people in the studies had symptoms like these after fundoplication surgery.

Possible serious complications of surgery include severe bleeding, organ injury and infections. Up to 2 out of 100 people have severe bleeding, and the digestive tract is injured in about 1 out of 100 people.

Home remedies for heartburn

Lifestyle changes may help reduce the frequency of acid reflux. Try to:

- Maintain a healthy weight. Excess pounds put pressure on your abdomen, pushing up your stomach and causing acid to reflux into your esophagus.

- Stop smoking. Smoking decreases the lower esophageal sphincter’s ability to function properly.

- Elevate the head of your bed. If you regularly experience heartburn while trying to sleep, place wood or cement blocks under the feet of your bed so that the head end is raised by 6 to 9 inches. If you can’t elevate your bed, you can insert a wedge between your mattress and box spring to elevate your body from the waist up. Raising your head with additional pillows isn’t effective.

- Don’t lie down after a meal. Wait at least three hours after eating before lying down or going to bed.

- Avoid late meals.

- Avoid large meals. Instead eat many small meals throughout the day.

- Eat food slowly and chew thoroughly. Put down your fork after every bite and pick it up again once you have chewed and swallowed that bite.

- Avoid foods and drinks that trigger reflux. Common triggers include fatty or fried foods, tomato sauce, alcohol, chocolate, mint, garlic, onion, and caffeine.

- Avoid tight-fitting clothing. Clothes that fit tightly around your waist put pressure on your abdomen and the lower esophageal sphincter.

Alternative medicine

No alternative medicine therapies have been proved to treat GERD or reverse damage to the esophagus. Some complementary and alternative therapies may provide some relief, when combined with your doctor’s care.

Talk to your doctor about what alternative GERD treatments may be safe for you. The options might include:

- Herbal remedies. Licorice and chamomile are sometimes used to ease GERD. Herbal remedies can have serious side effects and might interfere with medications. Ask your doctor about a safe dosage before beginning any herbal remedy.

- Relaxation therapies. Techniques to calm stress and anxiety may reduce signs and symptoms of GERD. Ask your doctor about relaxation techniques, such as progressive muscle relaxation or guided imagery.

- Antunes C, Aleem A, Curtis SA. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. [Updated 2022 Jul 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441938

- What is GERD? https://gi.org/topics/acid-reflux

- El-Serag HB, Petersen NJ, Carter J, et al. Gastroesophageal reflux among different racial groups in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1692–1699.

- El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, Dent J. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2014 Jun;63(6):871-80. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-304269

- Patti MG. An Evidence-Based Approach to the Treatment of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. JAMA Surg. 2016 Jan;151(1):73-8. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.4233

- Nilsson M, Johnsen R, Ye W, Hveem K, Lagergren J. Prevalence of gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms and the influence of age and sex. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004 Nov;39(11):1040-5. doi: 10.1080/00365520410003498

- Eusebi LH, Ratnakumaran R, Yuan Y, Solaymani-Dodaran M, Bazzoli F, Ford AC. Global prevalence of, and risk factors for, gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: a meta-analysis. Gut. 2018 Mar;67(3):430-440. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313589

- Kim SY, Jung HK, Lim J, Kim TO, Choe AR, Tae CH, Shim KN, Moon CM, Kim SE, Jung SA. Gender Specific Differences in Prevalence and Risk Factors for Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease. J Korean Med Sci. 2019 Jun 2;34(21):e158. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2019.34.e158

- Lin M, Gerson LB, Lascar R, Davila M, Triadafilopoulos G. Features of gastroesophageal reflux disease in women. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004 Aug;99(8):1442-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04147.x

- Badillo R, Francis D. Diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. 2014 Aug 6;5(3):105-12. doi: 10.4292/wjgpt.v5.i3.105

- Richter JE. Gastroesophageal reflux disease during pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin N Am 2003;32:235-61.

- Pregnancy in Gastrointestinal Disorders. http://s3.gi.org/physicians/PregnancyMonograph.pdf

- American College of Gastroenterology. http://gi.org/

- https://acgcdn.gi.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/07/media-releases-Pregnancy_Heartburn_Relief_120707.pdf

- Larson JD, et al., “Double-blind placebo-controlled study of ranitidine for gastroesophageal reflux symptoms during pregnancy.” Obstet Gynecol 1997; 90:83-7.

- Richter JE., “Gastroesophageal reflux disease during pregnancy. Gastroenterol Clin N Am 2003; 32:235-61.

- Committee on Drugs. American Academy of Pediatrics. The transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics 1994;93:131-50.

- Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, Blum AL, Armstrong D, Galmiche JP, Johnson F, Hongo M, Richter JE, Spechler SJ, Tytgat GN, Wallin L. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999 Aug;45(2):172-80. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1727604/pdf/v045p00172.pdf

- Katz PO, Gerson LB, Vela MF. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 Mar;108(3):308-28; quiz 329. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.444. Epub 2013 Feb 19. Erratum in: Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 Oct;108(10):1672.

- Kellerman R, Kintanar T. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease. Prim Care. 2017 Dec;44(4):561-573. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2017.07.001

- Wang KK, Sampliner RE; Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Updated guidelines 2008 for the diagnosis, surveillance and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Mar;103(3):788-97. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.01835.x

- Savarino E, Bredenoord AJ, Fox M, Pandolfino JE, Roman S, Gyawali CP; International Working Group for Disorders of Gastrointestinal Motility and Function. Expert consensus document: Advances in the physiological assessment and diagnosis of GERD. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017 Nov;14(11):665-676. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.130. Erratum in: Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Apr 06

- De Giorgi F, Palmiero M, Esposito I, Mosca F, Cuomo R. Pathophysiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2006 Oct;26(5):241-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2639970

- Mittal RK, McCallum RW. Characteristics and frequency of transient relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter in patients with reflux esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1988 Sep;95(3):593-9. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(88)80003-9

- Richter J. Do we know the cause of reflux disease? Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1999 Jun;11 Suppl 1:S3-9.

- Diener U, Patti MG, Molena D, Fisichella PM, Way LW. Esophageal dysmotility and gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Gastrointest Surg. 2001 May-Jun;5(3):260-5. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(01)80046-9

- Kahrilas PJ, Lin S, Chen J, Manka M. The effect of hiatus hernia on gastro-oesophageal junction pressure. Gut. 1999 Apr;44(4):476-82. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.4.476

- Patti MG, Goldberg HI, Arcerito M, Bortolasi L, Tong J, Way LW. Hiatal hernia size affects lower esophageal sphincter function, esophageal acid exposure, and the degree of mucosal injury. Am J Surg. 1996 Jan;171(1):182-6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)80096-8

- Ott DJ, Gelfand DW, Chen YM, Wu WC, Munitz HA. Predictive relationship of hiatal hernia to reflux esophagitis. Gastrointest Radiol. 1985;10(4):317-20. doi: 10.1007/BF01893120

- Corley DA, Kubo A, Zhao W, Quesenberry C. Proton pump inhibitors and histamine-2 receptor antagonists are associated with hip fractures among at-risk patients. Gastroenterology. 2010 Jul;139(1):93-101. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.03.055

- Markovits, N., Loebstein, R., Halkin, H., Bialik, M., Landes-Westerman, J., Lomnicky, J. and Kurnik, D. (2014), The association of proton pump inhibitors and hypomagnesemia in the community setting. The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 54: 889-895. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcph.316

- Bavishi, C. and DuPont, H.L. (2011), Systematic review: the use of proton pump inhibitors and increased susceptibility to enteric infection. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 34: 1269-1281. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04874.x

- Linsky A, Gupta K, Lawler EV, Fonda JR, Hermos JA. Proton Pump Inhibitors and Risk for Recurrent Clostridium difficile Infection. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(9):772–778. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.73

- Freedberg DE, Salmasian H, Friedman C, Abrams JA. Proton pump inhibitors and risk for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection among inpatients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 Nov;108(11):1794-801. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.333

- Gerson L, Stouch B, Lobonţiu A. Transoral Incisionless Fundoplication (TIF 2.0): A Meta-Analysis of Three Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trials. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2018 Mar-Apr;113(2):173-184. https://revistachirurgia.ro/pdfs/2018-2-173.pdf

- Testoni PA, Testoni S, Distefano G, Mazzoleni G, Fanti L, Passaretti S. Transoral incisionless fundoplication with EsophyX for gastroesophageal reflux disease: clinical efficacy is maintained up to 10 years. Endosc Int Open. 2019 May;7(5):E647-E654. doi: 10.1055/a-0820-2297

- Skubleny D, Switzer NJ, Dang J, Gill RS, Shi X, de Gara C, Birch DW, Wong C, Hutter MM, Karmali S. LINX® magnetic esophageal sphincter augmentation versus Nissen fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Surg Endosc. 2017 Aug;31(8):3078-3084. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5370-3

- InformedHealth.org [Internet]. Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG); 2006-. Heartburn and GERD: Treatment options for GERD. 2012 Jul 19 [Updated 2018 Dec 13]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279252