What is a groin strain

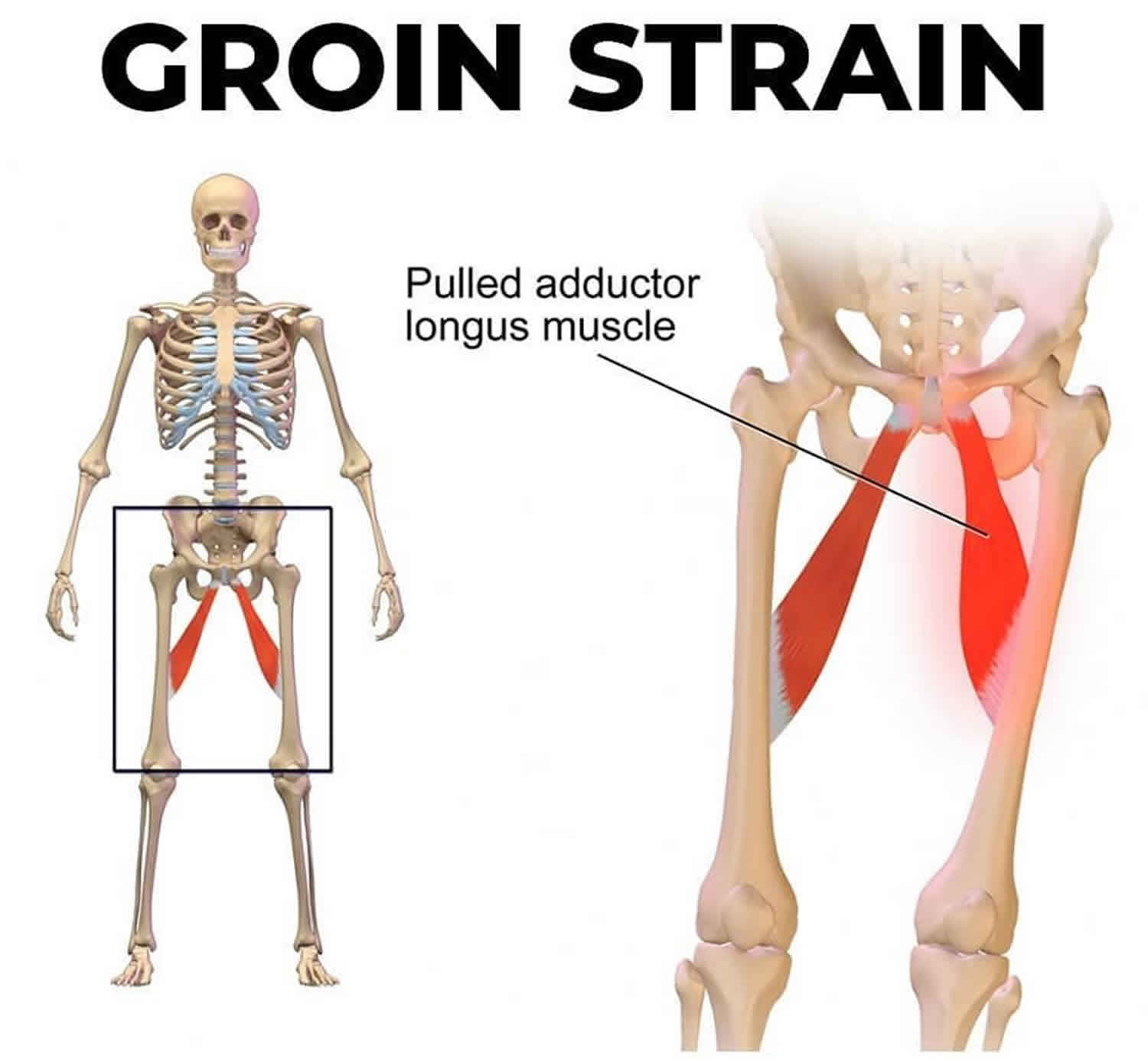

A groin strain is an injury that happens when you tear or overstretch (pull) a groin muscle called hip adductors (Figure 1) 1, 2, 3, 4. The groin muscles (hip adductors) are in the area on either side of your body in the folds where your belly joins your legs. You can strain a groin muscle during exercise, such as running, skating, ice hockey, fencing, handball, cross country skiing, hurdling, high jumping, kicking in soccer or playing basketball. A groin strain can happen when you lift, push, or pull heavy objects. You might also pull a groin muscle when you fall. The groin muscle strain injury can range from a minor pull to a more serious tear of the muscle. The diagnosis is often frustrating for both the athlete and the physician, and remains unclear in approximately 30 percent of cases 5. Factors that complicate the diagnosis include the complex anatomy of the region and the frequent coexistence of two or more disorders 6. In one study5 of 21 patients with groin pain, 19 patients were found to have two or more disorders. The investigators concluded that groin pain in athletes is complex and can be difficult to evaluate even by experienced physicians 7. From an anatomical point of view, various causes of groin pain can be considered under the headings of intra-articular and extra-articular causes 8, 9, 10, 7, 11. The intra-articular causes consists of lesions arising within the ball and socket of the hip joint, while the extra-articular causes includes conditions arising from outside the ball and socket joint 12. Experts estimate that 60% of intra-articular injuries are initially misdiagnosed as extra-articular 13. However, hip adductor strains are usually easily diagnosed on physical examination with pain on palpation of the involved muscle and pain on adduction against resistance 10. Hip adductor strains must, however, be distinguished from osteitis pubis and “sports hernias,” which can present with pain in similar locations 6, 14, 14.

A groin strain is a common problem among many individuals who are physically active, especially in competitive sports. Between 2 and 5 percent of all sports injuries occur in the groin area and groin injuries have a high recurrence rate of between 15% and 31% 15, 3, 4, 14. The most common sports that put athletes at risk for adductor strains are football, soccer, hockey, basketball, tennis, figure skating, baseball, horseback riding, karate, and softball 16. In fact, as many as 10% of ice hockey–related injuries and 10 to 18% of soccer-related injuries are groin injuries 17, 18, 4, 19. Among European soccer players, adductor muscle injuries were the second most commonly injured muscle group (23%) behind hamstrings (37%). In another study of soccer players, adductor pain/strain represents anywhere from 9% to 18% of all injuries. In sub-elite, male soccer players, adductor strain accounted for 51% of all groin pain.

Hip adductor injuries occur most commonly when there is a forced push-off (side-to-side motion). High forces occur in the adductor tendons when the athlete must shift direction suddenly in the opposite direction. As a result, the adductor muscles contract to generate opposing forces.

One common cause of adductor strain in soccer players has been attributed to forceful abduction of the thigh during an intentional adduction. This type of motion occurs when the athlete attempts to kick the ball and meets resistance from the opposing player who is trying to kick the ball in the opposite direction. To a lesser extent, jumping also can cause injury to the adductor muscles, but more commonly, it involves the hip flexors. Overstretching of the adductor muscles is a less common cause.

You may feel pain and tenderness that’s worse when you squeeze your legs together. You may also have pain when you raise the knee of the injured side. There may be swelling or bruising in the groin area or inner thigh. If you have a bad strain, you may walk with a limp while it heals.

Rest and other home care can help the muscle heal. Healing can take up to 3 weeks or more. Your doctor may want to see you again in 2 to 3 weeks.

Groin strain staging

Groin strain has a 3-tier classification system.

- First degree: Pain without significant loss of strength or range of motion

- Second degree: Pain with loss of strength

- Third degree: Complete disruption of muscle or tendon fibers with loss of strength

How to heal a groin strain at home

- Rest and protect your injured or sore groin area for 1 to 2 weeks. Stop, change, or take a break from any activity that may be causing your pain or soreness. Rest is essential to heal any strains or sprains to your groin.

- Do not do intense activities while you still have pain.

- Put ice or a cold pack on your groin area for 10 to 20 minutes at a time. Try to do this every 1 to 2 hours for the next 3 days (when you are awake) or until the swelling goes down. Put a thin cloth between the ice and your skin.

- After 2 or 3 days, if your swelling is gone, apply heat. Put a warm water bottle, a heating pad set on low, or a warm cloth on your groin area. Do not go to sleep with a heating pad on your skin.

- If your doctor gave you crutches, make sure you use them as directed.

- Take an over-the-counter pain reliever such as ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) or acetaminophen (Tylenol, others).

- Wear snug shorts or underwear that support the injured area.

See your doctor now or seek immediate medical care if:

- You have new or severe pain or swelling in the groin area.

- Groin pain associated with back, abdomen or chest pain.

- Your groin or upper thigh is cool or pale or changes color.

- You have tingling, weakness, or numbness in your groin or leg.

- You cannot move your leg.

- You cannot put weight on your leg.

- Sudden, severe testicle pain.

- Testicle pain and swelling accompanied by nausea, vomiting, fever, chills or blood in the urine.

Watch closely for changes in your health, and be sure to contact your doctor if:

- Groin pain that doesn’t improve with home treatment within a few days

- Mild testicle pain lasting longer than a few days

- A lump or swelling in or around a testicle

- Intermittent intense pain along the lower side of your abdomen (flank) that may radiate along your groin and into your testicle

- Blood in your urine

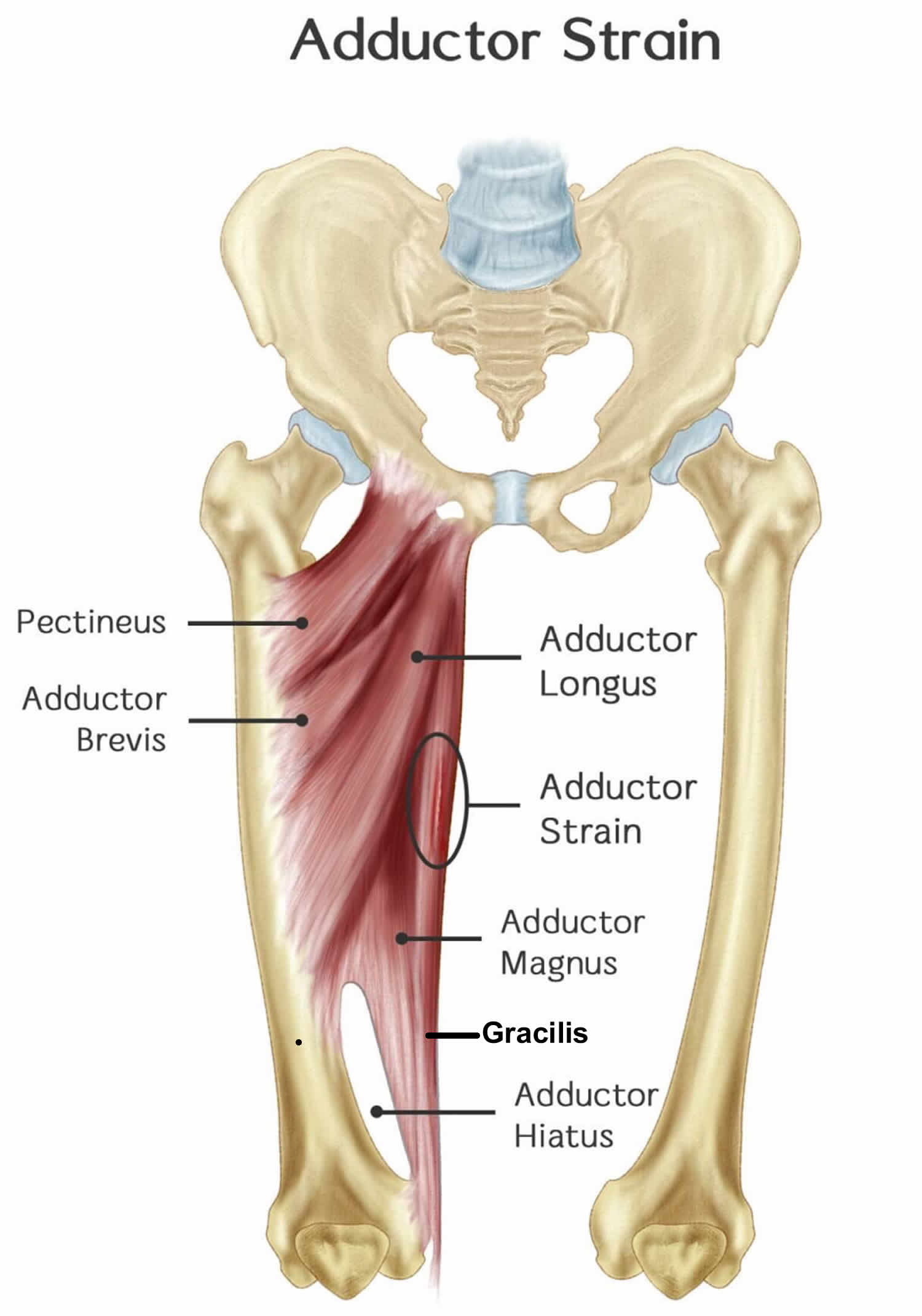

Hip adductors

Hip adductor complex includes the three adductor muscles (longus, magnus, and brevis) of which the adductor longus is most commonly injured 20. All three muscles primarily provide adduction of the thigh 20. Adductor longus provides some medial rotation. The adductor magnus also has an attachment on the ischial tuberosity, giving it the ability to extend the hip. In open chain activation, the primary function is hip adduction. In closed chain activation, they help stabilize the pelvis and lower extremity during the stance phase of gait. They also have secondary roles including hip flexion and rotation 21, 22.

Adductor Magnus

- Origin: Inferior pubic ramus, ischial tuberosity

- Insertion: Linea aspera, adductor tubercle

Adductor Brevis

- Origin: Inferior pubic ramus

- Insertion: Linea aspera, pectineal line

Adductor Longus

- Origin: Anterior pubic ramus

- Insertion: Linea aspera

The primary hip adductor complex is accompanied by three additional muscles with adduction activity including the gracilis, which also participates in internal rotation and hip flexion; obturator externus, which can also externally rotate; and pectineus, which additionally assists in hip flexion.

Gracilis

- Origin: Inferior pubic symphysis, pubic arch

- Insertion: Proximal medial tibia, pes anserine

Pectineus

- Origin: Pectineal line of pubis

- Insertion: Pectineal line of femur

Obturator Externus

- Origin: Obturator foramen

- Insertion: Posterior aspect of the greater trochanter

The obturator nerve (L2 to L4), arising from the lumbar plexus, innervates all three. The adductor magnus also is innervated by the tibial nerve (L4 through S3).

Figure 1. Hip adductors

Groin strain causes

Groin strain is a common injury among soccer and hockey players. Other common sports related to adductor strain include football, basketball, tennis, figure skating, baseball, horseback riding, karate, and softball. Risk factors include previous hip or groin injury, which is likely the greatest risk, as well as age, weak adductors, muscle fatigue, decreased range of motion, and inadequate stretching of the adductor muscle complex. Biomechanical abnormalities including excessive pronation or leg-length discrepancy can also contribute 23.

Suddenly changing direction causes rapid adduction of the hip against an abduction force, putting exaggerated stress on the tendon. Sudden acceleration in sprinting is the most common mechanism of injury. Jumping and overstretching the adductor tendon are less common causes.

Nonathletic causes of groin pain

Differential diagnosis of nonathletic causes of groin pain 6:

- Intra-abdominal disorders (e.g., aneurysm, appendicitis, diverticulosis, inflammatory bowel disease)

- Genitourinary abnormalities (e.g., urinary tract infection, lymphadenitis, prostatitis, scrotal and testicular abnormalities, gynecologic abnormalities, nephrolithiasis)

- Referred lumbosacral pain (e.g., lumbar disc disease)

- Hip joint disorders (e.g., Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, synovitis, slipped femoral capital epiphysis in younger patients and osteochondritis disse-cans of femoral head, avascular necrosis of the femoral head, osteoarthritis, acetabular labral tears)

Groin strain pathophysiology

Most muscle tendon strains occur while the muscle is being forcibly stretched while being concentrically contracted. The greatest eccentric tension is placed on the adductor complex when the leg is in external rotation and abduction. Adductor injuries typically occur when the athlete pushes off in the opposite direction. As a result, the adductor muscles contract to generate both eccentric and concentric opposing forces. The dominant leg is more commonly injured and more likely to sustain significant injury.

For example, a soccer player trying to kick a ball with an externally rotated leg using the inside of their foot. If their leg swinging in adduction meets a significant resistive abductive force such as another player, this can place a significant load on the adductor complex leading to injury.

The musculotendinous junction is the most common site of injury in a muscle strain. The adductor tendons have a small insertion zone which is characterized by an area of poor blood supply and rich nerve supply which helps explain the increased degree of perceived pain.

The adductor longus is the most commonly injured muscle and accounts for 62% to 90% of cases. It is hypothesized that this occurs due to its low tendon to muscle ratio at the origin. Rugby players with adductor-abductor strength ratio of less than 80% are 17 times more likely to sustain an adductor injury 24.

Groin strain differential diagnosis

The musculoskeletal differential diagnosis of groin pain is broad and includes tendonitis (iliopsoas, rectus femoris), bursitis (iliopsoas), athletic pubalgia (sports hernia, sportsman’s hernia, pre-hernia complex, Gilmore groin), hip joint pathology (osteoarthritis, femora-acetabular impingement, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, avascular necrosis), osteitis pubis, sacroiliac dysfunction, neuropathic pain (radiculopathy, sciatica), and mechanical low back pain.

Nonmusculoskeletal causes of groin pain include urologic disorders, malignancy, gastrointestinal disorders, sexually transmitted infections, and, in women, gynecologic disorders.

Table 1 below shows the common intra-articular causes for groin pain in athletes with their clinical findings and related references. The common extra-articular causes for groin pain in athletes with their clinical findings and related references are outlined in Table 2.

Table 1. Intra-articular causes of groin pain in athletes

| Common intra-articular pathologies causing groin pain | ||

|---|---|---|

| Conditions | Findings | |

| 1 | Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) | Sharp anterior hip pain with deep flexion, internal rotation or abduction. Limited internal rotation and adduction in flexion. Positive impingement test. |

| 2 | Chondrolabral injuries | Dull groin pain, worsens with activities like prolonged sitting, walking. Restricted terminal hip range of movements. Locking, clicking, giving way. |

| 3 | Injuries to the ligamentum teres | Hip stiffness. Giving way. Reduced range of motion. |

| 4 | Loose bodies | Anterior groin pain. Catching, locking, clicking or giving way. Limited range of movements. |

Table 2. Extra-articular causes of groin pain in athletes

| Common extra-articular pathologies causing groin pain | ||

|---|---|---|

| Conditions | Findings | |

| 1 | Muscle strain/tears | Aching groin or medial thigh pain and may or may not relate a specific inciting incident. Painful restriction of movements especially adduction. Localised tenderness and focal swelling along adductors. Decreased adductor strength. |

| 2 | Stress fracture | Exercise induced pain in hip, groin, thigh or referred to knee that aggravates at night. Sudden worsening of groin pain suggests completion of fracture. |

| 3 | Osteitis pubis | Anterior hip pain radiating to suprapubic area. Localised tenderness over pubic symphysis. |

| 4 | Sports hernia | Insidious onset of groin pain on activity. Pain aggravates on sudden movements like coughing, sneezing, kicking and sprints. |

| 5 | Snapping syndromes | Groin pain that aggravates on movements. Intermittent catching, locking of hip. |

| 6 | Nerve entrapment | Groin pain associated with burning sensation. Altered sensation along the distribution of nerve. Weakness of affected group of muscles. |

Groin strain symptoms

Patients will often describe a sudden onset of pain during a specific activity as opposed to a more insidious onset. They will describe the pain as severe and in the groin region or medial thigh that is worse with activity.

Generally, symptoms are more diffuse, with typical complaints of pain and stiffness in the groin region in the morning and at the beginning of athletic activity. Initial intense pain lasts less than a second. This initial pain is soon replaced with an intense dull ache. Pain severity can vary with different patients. Pain and stiffness often resolve after a period of warming up but often recur after athletic activity.

Individuals can sustain injury anywhere along the medial compartment of the thigh along the adductor complex. The clinician may observe bruising or swelling in moderate to severe injuries. Typically, there is an area of point tenderness or localized tenderness at the origin of the adductor longus and/or the gracilis located at the inferior pubic ramus and pain with resisted adduction. The patient will have pain with resisted adduction of the hip or with passive stretching. They may have decreased strength secondary to pain, or depending on the degree of injury, this strength deficit may be due to muscle or tendon rupture or avulsion injury.

Usually, pain is described at the site of the adductor longus tendon proximally, especially with rapid adduction of the thigh. As the injury becomes more chronic, pain may radiate distally along the medial aspect of the thigh and/or proximally toward the rectus abdominis. Acute injuries are described as a sudden ripping or stabbing pain in the groin, and chronic injuries are described as a diffuse dull ache.

Exercise-induced medial thigh pain over the area of the adductors, especially after kicking and twisting, may indicate obturator neuropathy. Pain at the symphysis pubis or scrotum may be more consistent with osteitis pubis. Conjoined tendon lesions present as pain that radiates upward into the rectus abdominis or laterally along the inguinal ligament; exquisite tenderness is present at the site of the injury.

True loss of function is not observed unless a grade 3 tear is present. In the case of a severe tear, loss of hip adduction occurs. Loss of function also should alert the physician to possible nerve involvement (obturator nerve entrapment).

Groin strain complications

Complications of groin strains primarily include acute pain and missed playing time. In some cases, the pain may be more chronic with associated weakness and inability to return to sport.

Because sport-related groin injuries are a significant contributor to missed playing time, prevention is essential in maintaining a healthy athlete. Prevention programs are directed at adductor strengthening. Maintaining adductor strength at a minimum of 80% of abductor strength has been shown to reduce adductor injuries. One program among NHL players identified as having weak abductors participated in a 6-week preseason strengthening program which reduced adductor strains from 3.2 injuries per 1000 player-game exposures to 0.71.

Groin strain diagnosis

Although the diagnosis for suspected adductor strain is usually made clinically, radiographic evaluation can be helpful in excluding fractures or avulsions 19. Anteroposterior views of the pelvis and frog leg view of the affected hip are recommended as initial imaging studies. In most patients, these images will be normal in appearance; however, occasionally one may observe an avulsion injury. These images can also help evaluate for other causes of groin pain such as osteitis pubis, apophyseal avulsion fractures, and pelvic or hip stress fractures. If the diagnosis is in question, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to confirm muscle strain or tears, and partial and complete tendon tears. This is likely to show muscle edema and hemorrhage at the site of injury. If there is a bony injury, this will be better elucidated on the MRI. Musculoskeletal ultrasound is useful for diagnosing muscle and tendon tears, but not muscle strains 25. Ultrasound can be used to identify the area and extent of the injury and used to evaluate periodically during the recovery phase. The most common site of strain is the musculotendinous junction of the adductor longus or gracilis. Complete avulsions of these tendons also occur, but much less frequently.

Once the diagnosis of adductor strain has been established, three questions must be considered 6:

- First, are there biomechanical abnormalities that may predispose to injury? Foot and lower leg malalignment, muscular imbalances, leg length discrepancy, gait or sport-specific motion abnormalities can all theoretically place abnormal loads on the adductors. Although controlled clinical studies demonstrating a causal relationship between biomechanical abnormalities and adductor strains have not been conducted, many physicians specializing in sports medicine believe that these are important contributing factors 19. If present, these abnormalities should be evaluated and corrected if possible.

- Second, what is the location of the tear? This has important therapeutic and prognostic implications. If an acute tear occurs at the musculotendinous junction, a relatively aggressive approach to rehabilitative treatment can be undertaken. When an acute partial tear occurs at the tendinous insertion of the adductors into the pubic bone, a period of rest must be completed before pain-free physical therapy is possible 26.

- Third, what is the chronicity of the symptoms? Athletes often do not recall an acute inciting incident and complain instead of pain of an insidious onset. These athletes are difficult to treat because they remain able to play their sports (at least for a while) after a good warm-up and are not motivated to take time off and undergo proper rehabilitation.

Figure 2. Groin strain diagnostic algorithm

[Source 14 ]Groin strain treatment

Most groin (adductor) strains are managed conservatively 20. Few controlled studies of the treatment of adductor strains exist in the literature and most clinical experience dictates that acute treatment include physical therapy modalities (i.e., rest, ice, compression, elevation) that help prevent further injury and inflammation 6. Initial management will include protection, relative rest from sports, ice, compression, analgesia and physical therapy (PRICE therapy). The use of crutches during the first few days may be indicated to relieve pain. Analgesia typically includes acetaminophen and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medications. The rehabilitation program should include stretching, the range of motion and strengthening of the affected leg and core accompanied by a gradual return to sport.

Following this, the goal of therapy should be restoration of range of motion and prevention of atrophy. Finally, the patient should regain strength, flexibility and endurance 19. Physical therapy should be directed at strength, the range of motion, and stretching of the affected muscle group. Return to play and activity should be guided by symptom recovery as well as physician and therapist guidance. Returning players to activity too soon can result in recurrent or chronic injuries and be detrimental to their future career. When the athlete has regained at least 70 percent of his or her strength and pain-free full range of motion, a return to sport may be allowed 27. This return may take four to eight weeks following an acute musculotendinous strain and up to six months for chronic strains 19, 28, 29.

In addition, other treatment modalities may be available for refractory cases. This includes corticosteroid injection into the adductor complex and needle tenotomy, both of which are at the discretion of the consulting physician and typically performed under ultrasound guidance.

Occasionally, surgical management is indicated. There are no clear guidelines on which injuries require surgical management. Potential indications include poor recovery with conservative management with full-thickness tears or avulsion injuries with the persistent weakness of the affected limb.

One randomized trial of 68 athletes with chronic adductor strain11 compared physical therapy (i.e., friction massage, stretching, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, laser treatment) with active training exercise 30. A significantly greater number of participants (23 versus four in the physical therapy group) were able to return to their sport after an eight- to 12-week active training program 30. Further studies may corroborate this initial investigation, and active training methods may be the future in treating acute and chronic adductor strains. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and steroid injections have been mentioned in the treatment of these conditions, but their efficacy is debatable and lacks support in the literature 19.

Patients with chronic adductor longus strains that have failed to respond to several months of conservative treatment have been shown to do well after surgical tenotomy and should be referred to a sports medicine surgeon for this consideration 31, 32. Complete tears of the tendinous insertion from the bone, though rare, generally do better with surgical repair 27.

Chronic groin strain

Rest, ice, massage, and therapeutic ultrasonography have been recommended to treat long-standing groin pain. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and steroid injections have been suggested but have not been supported by controlled trials. Forceful adductor stretch under general anesthetic has been recommended. A careful monitored program with a total cessation of the sports activity is necessary for the chronic adductor injury to heal and become pain-free.

The physical therapy program should consist of isometric exercises, strengthening of the hip- and pelvis-stabilizing muscles, and proprioceptive training. No increase in pain should be experienced during or after the exercises. The load of the exercises is gradually increased. Specific strengthening of the adductor muscles is then implemented.

Cycling can be used to maintain general conditioning, but running can begin only after the patient can perform the exercises at high intensity without pain. Sprinting and cutting activities may then follow. Sport-specific training is the final step before full return to sport. This part of the rehabilitation program may take 3-6 months.

Adductor strain post injury program

Despite the identification of risk factors and strengthening intervention for ice hockey players, adductor strains continue to occur in all sports 33. The high incidence of recurrent adductor strains could be due to incomplete rehabilitation or inadequate time for complete tissue repair 29. Hölmich et al 30 demonstrated that a passive physical therapy program of massage, stretching, and modalities was ineffective in treating chronic groin strains. By contrast, an 8‐12 week active strengthening program consisting of progressive resistive adduction and abduction exercises, balance training, abdominal strengthening, and skating movements on a slide board proved more effective in treating chronic groin strains. An increased emphasis on strengthening exercises may reduce the recurrence rate of groin strains. An adductor muscle strain injury rehabilitation program progressing the athlete through the phases of healing has been developed by Tyler et al 34 and anecdotally seems to be effective. As displayed below, this type of treatment regimen combines modalities and passive treatment immediately, followed by an active training program emphasizing eccentric resistive exercise. This method of rehabilitation progressing patients through phases of rehabilitation using clinical milestones has been supported throughout the literature 35, 33.

Phase 1: Acute

- RICE (rest, ice, compression and elevation) for first ‐48 hours after injury

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Massage

- TENS (Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation)

- Ultrasound

- Submaximal isometric adduction with knees bent→with knees straight progressing to maximal isometric adduction, pain free

- Hip passive range of motion (PROM) in pain‐free range

- Nonweight‐bearing hip progressive resistive exercises (PREs) without weight in anti‐gravity position (all except abduction), pain‐free, low load, high repetition exercise

- Upper body & trunk strengthening

- Contralateral lower extremity strengthening

- Flexibility program for noninvolved muscles

- Bilateral balance board

Clinical milestone

Concentric adduction against gravity without pain.

Phase 2: Subacute

- Bicycling or swimming

- Sumo squats

- Single limb stance

- Concentric adduction with weight against gravity

- Standing with involved foot on sliding board moving in frontal plane

- Adduction in standing on cable column or Theraband

- Seated adduction machine

- Bilateral adduction on sliding board moving in frontal plane (i.e. bilateral adduction simultaneously)

- Unilateral lunges (sagittal) with reciprocal arm movements

- Multiplane trunk tilting

- Balance board squats with throwbacks

- General flexibility program

Clinical milestone

Involved lower extremity passive range of motion (PROM) equal to that of the uninvolved side and involved adductor strength at least 75% that of the ipsilateral abductors 29.

Phase 3: Sports Specific Training

- Phase 2 exercises with increase in load, intensity, speed and volume

- Standing resisted stride lengths on cable column to simulate skating

- Slide board

- On ice kneeling adductor pull togethers

- Lunges (in all planes)

- Correct or modify ice skating technique

Clinical milestone

Adduction strength at least 90‐100% of the abduction strength and involved muscle strength equal to that of the contralateral side 29.

Groin strain stretches

Some authorities believe that stretching in the acute phase may aggravate the condition and lead to a chronic lesion. Control of muscle spasms is important for rehabilitation. Spasms may be alleviated with medication and/or modalities (eg, ice, electrical muscle stimulation). Passive range-of-motion (PROM) exercises are initiated when the patient can perform them without pain. Active muscle exercises can be advanced slowly from isometric contractions without resistance, to isometrics with resistance, progressing eventually to dynamic exercises when tolerated with little or no pain 36.

Strengthening abdominal and hip flexor muscles is an essential part of rehabilitation of groin injuries. Coactivation of the abdominal muscles and the adductor muscles is a useful and functional exercise. Completing many repetitions increases the endurance of the adductor muscles. A fatigued muscle/tendon complex is more vulnerable to injury. The patient should aim to progress gradually to 30-40 repetitions. Proprioceptive exercises are recommended, along with stretching, as well as an aquatic training program if accessible. After several days, heat and support bandages are recommended.

Groin strain exercises

Grade 1 groin strain

Pain-free hip stretching exercises can begin immediately. Pain-free progressive strengthening exercises can also be initiated immediately and can progress to include hip flexion (with knee straight and bent) and adduction.

Therapy may be advanced to include the slide board, plyometrics (lateral sliding, lateral lunges, and X lunges), and, finally, sport-specific functional drills. (See the images below of lateral and X lunges.) The athlete may not be required to miss competition time, depending on the severity of the injury.

Grade 2 groin strain

Therapy should begin immediately with gentle pain-free active range-of-motion (AROM) exercises of the hip. Isometric exercises should be initiated as soon as the patient can perform them without pain.

After 1 week, pain-free slide board exercises and plyometrics can be initiated. Soon after the first week, sport-specific functional drills can begin. An athlete with a grade 2 groin strain may miss 3-14 days of competition, depending on the severity of the injury.

Grade 3 groin strain (nonsurgical)

Therapy includes PRICE plus a non–weight-bearing restriction for acute strains. Rest is required for 1-3 days, with continuous compression. If surgery is not indicated, pain-free isometric exercises and slow, pain-free active range-of-motion (AROM) exercises can be started between days 3 and 5. The athlete should continue to use crutches until normal pain-free ambulation is possible.

Initiate pain-free stretching exercises, progressive-resistance strengthening exercises (without pain), and proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF) between days 7 and 10.

Usually within 10 days after starting progressive-resistance strengthening exercises, the patient should be able to perform pain-free slide board exercises and plyometrics and eventually advance to sport-specific functional activities.

Adductor Strain Injury Prevention Program

Adductor muscle strength has been associated with a subsequent muscle strain 29. As researchers have begun to identify players at risk for a future adductor strain, the next step is to design and investigate an intervention program to address all risk factors. Tyler et al 34 were able to demonstrate that a therapeutic intervention of strengthening the adductor muscle group could be an effective method for preventing adductor strains in professional ice hockey players. Prior to the 2000 and 2001 seasons, professional ice hockey players were strength tested. Thirty‐three of these 58 players were classified as “at risk” which was defined as having an adduction to abduction strength ratio of less than 80% and placed on an intervention program. The intervention program consisted of strengthening and functional exercises aimed at increasing adductor strength 29.

Warm‐up

- Bike

- Adductor stretching

- Sumo squats

- Side lunges

- Kneeling pelvic tilts

Strengthening program

- Ball squeezes (legs bent to legs straight)

- Different ball sizes

- Concentric adduction with weight against gravity

- Adduction in standing on cable column or elastic resistance

- Seated adduction machine

- Standing with involved foot on sliding board moving in sagittal plane

- Bilateral adduction on sliding board moving in frontal plane (i.e. bilateral adduction simultaneously)

- Unilateral lunges with reciprocal arm movements

Sports specific training

- On ice kneeling adductor pull togethers

- Standing resisted stride lengths on cable column to simulate skating

- Slide skating

- Cable column crossover pulls

Clinical Goal

Adduction strength at least 80% of the abduction strength 29.

Surgical approach to rupture and Chronic groin strains

Surgery is indicated in acute strains only when there is rupture and in select chronic strains that are refractory to conservative treatment. In the surgical procedure, the patient is in the supine position with the knee in 90° of flexion and the hip in 45° of flexion. The adductor longus tendon is identified, and a skin incision is made. A discoloration of the tendon or a swelling indicates an old partial rupture. The tendon then is opened longitudinally. Occasionally, granulation tissue is found and excised. If there are no findings in the tendon, a tenotomy may be performed 37.

A tenotomy is described in an article by Martems et al 38. The region is infiltrated with lidocaine and epinephrine. A stab wound is made just underneath the adductor longus muscle, close to the os pubis. The insertion of the gracilis muscle and a portion of the adductor brevis are sectioned subcutaneously. The adductor longus tendon is left intact. A compression bandage is then applied for 24 hours. The patient may walk after 2 days and may resume running within pain limits 5 weeks postoperatively. The usual time to return to unrestricted sports activities is 10-12 weeks. In this study, there was no loss of power in the surgical group compared with the control group.

Although surgery has traditionally been recommended for adductor tendon rupture, a question exists as to whether attachment of the proximal adductor longus tendon to the pubis is necessary for high-level physical functioniong. In a study of 19 National Football League players with adductor tendon rupture, 14 of whom were treated nonoperatively and 5 of whom underwent surgical tendon repair with suture anchors, Schlegel et al determined that the players who received nonoperative therapy tended to return to play sooner than those who were surgically treated (mean time to return: 6.1 weeks vs 12 weeks, respectively) 39.

Groin strain recovery time

Do not return too quickly back to your sport, as groin muscle strain may become a chronic condition. Acute strains easily can become chronic strains if proper time is not allowed for healing. Chronic strains are much more difficult to manage.

Acute injuries may return as quickly as 4 to 8 weeks while chronic strains may take many months to achieve desired results 40.

Improper management of acute adductor strains or returning to play before pain-free sport-specific activities can be performed may lead to chronic injury 41. According Renstrom and Peterson 42, 42% of athletes with groin muscle-tendon injuries could not return to physical activity after more than 20 weeks following the initial injury. This prolonged length of time seems to indicate the importance of proper management of these injuries in the acute stage.

Groin strain prognosis

The prognosis for groin strains is generally good 20. Most athletes will return to play with minimal pain and normal function if provided appropriate relative rest and rehabilitation. If they return to play too soon or are inadequately rehabilitated, their pain may lead to chronic injury 20.

Renstrom et al. 43, 27 found that 42% of athletes with muscle-tendon groin injuries were not able to return to physical activity more than 20 weeks after the initial injury. However, an active training program directed at strength and conditioning of muscles of the pelvis and especially the adductor muscles is very effective at treating patients with long-standing, adductor-related groin pain 29, 44.

References- Werner J, Hagglund M, Walden M, et al. UEFA injury study: a prospective study of hip and groin injuries in professional football over seven consecutive seasons. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(13):1036–1040. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.066944

- Ekstrand J, Hilding J. The incidence and differential diagnosis of acute groin injuries in male soccer players. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1999;9(2):98–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1999.tb00216.x

- Karlsson J, Swärd L, Kälebo P, Thomée R. Chronic groin injuries in athletes. Recommendations for treatment and rehabilitation. Sports Med. 1994 Feb;17(2):141-8. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199417020-00006

- Renström P, Peterson L. Groin injuries in athletes. Br J Sports Med. 1980 Mar;14(1):30-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1858784/pdf/brjsmed00257-0032.pdf

- Roos HP: Hip pain in sport. Sports Med Arthroscopy Rev 1997, 5:292–300.

- Groin Injuries in Athletes. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(8):1405-1415. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2001/1015/p1405.html

- Ekberg O, Persson NH, Abrahamsson PA, Westlin NE, Lilja B. Longstanding groin pain in athletes. A multidisciplinary approach. Sports Med. 1988 Jul;6(1):56-61. doi: 10.2165/00007256-198806010-00006

- Byrd JWT (1998) in Operative hip arthroscopy, investigation of the symptomatic hip: physical examination. New York, Thieme; pp. 25–41.

- Shetty VD. Persistent anterior hip pain in young adults: current aspects of diagnosis. Hip Int. 2008 Jan-Mar;18(1):61-7. doi: 10.1177/112070000801800112

- Hoelmich P (1997) Adductor-related groin pain in athletes. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 5, 285–291.

- Jagtap P, Shetty G, Mane P, Shetty V. Emerging intra-articular causes of groin pain in athletes. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014 Dec;24(8):1331-9. doi: 10.1007/s00590-013-1325-8

- Nofsinger CC, Kelly BT (2007) Methodical approach to the history and physical exam of athletic groin pain. Oper Tech Sports Med 15, 152–156.

- Byrd JW, Jones KS. Hip arthroscopy in athletes. Clin Sports Med. 2001 Oct;20(4):749-61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-5919(05)70282-9

- Shetty VD, Shetty NS, Shetty AP. Groin pain in athletes: a novel diagnostic approach. SICOT J. 2015 Jul 7;1:16. doi: 10.1051/sicotj/2015017

- Werner J, Hägglund M, Waldén M, Ekstrand J. UEFA injury study: a prospective study of hip and groin injuries in professional football over seven consecutive seasons. Br J Sports Med. 2009 Dec;43(13):1036-40. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2009.066944

- Kiel J, Kaiser K. Adductor Strain. [Updated 2018 Dec 13]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493166

- Gilmore J. Groin pain in the soccer athlete: fact, fiction, and treatment. Clin Sports Med. 1998 Oct;17(4):787-93, vii. doi: 10.1016/s0278-5919(05)70119-8

- Westlin N. Groin pain in athletes from Southern Sweden. Sports Med Arthroscopy Rev. 1997;5:280-4.

- Hoelmich P. Adductor-related groin pain in athletes. Sports Med Arthroscopy Rev. 1997;5:285-91.

- Kiel J, Kaiser K. Adductor Strain. [Updated 2023 Jun 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493166

- Serner A, Mosler AB, Tol JL, Bahr R, Weir A. Mechanisms of acute adductor longus injuries in male football players: a systematic visual video analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2019 Feb;53(3):158-164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099246

- Feldman K, Franck C, Schauerte C. Management of a nonathlete with a traumatic groin strain and osteitis pubis using manual therapy and therapeutic exercise: A case report. Physiother Theory Pract. 2020 Jun;36(6):753-760. https://doi.org/10.1080/09593985.2018.1492658

- Mosler AB, Weir A, Serner A, Agricola R, Eirale C, Farooq A, Bakken A, Thorborg K, Whiteley RJ, Hölmich P, Bahr R, Crossley KM. Musculoskeletal Screening Tests and Bony Hip Morphology Cannot Identify Male Professional Soccer Players at Risk of Groin Injuries: A 2-Year Prospective Cohort Study. Am J Sports Med. 2018 May;46(6):1294-1305.

- Eckard TG, Padua DA, Dompier TP, Dalton SL, Thorborg K, Kerr ZY. Epidemiology of Hip Flexor and Hip Adductor Strains in National Collegiate Athletic Association Athletes, 2009/2010-2014/2015. Am J Sports Med. 2017 Oct;45(12):2713-2722. doi: 10.1177/0363546517716179

- Karlsson J, Jerre R. The use of radiography, magnetic resonance, and ultrasound in the diagnosis of hip, pelvis, and groin injuries. Sports Med Arthroscopy Rev. 1997;5:268-73.

- Fricker PA. Management of groin pain in athletes. Br J Sports Med. 1997;31:97-101. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1332605/pdf/brjsmed00002-0013.pdf

- Lynch SA, Renström PA. Groin injuries in sport: treatment strategies. Sports Med. 1999 Aug;28(2):137-44. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199928020-00006

- Dahan R. Rehabilitation of muscle-tendon injuries to the hip, pelvis, and groin areas. Sports Med Arthroscopy Rev. 1997;3:326-33.

- Tyler TF, Fukunaga T, Gellert J. Rehabilitation of soft tissue injuries of the hip and pelvis. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2014 Nov;9(6):785-97. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4223288

- Hölmich P, Uhrskou P, Ulnits L, Kanstrup IL, Nielsen MB, Bjerg AM, Krogsgaard K. Effectiveness of active physical training as treatment for long-standing adductor-related groin pain in athletes: randomised trial. Lancet. 1999 Feb 6;353(9151):439-43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)03340-6

- Akermark C, Johansson C. Tenotomy of the adductor longus tendon in the treatment of chronic groin pain in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 1992 Nov-Dec;20(6):640-3. doi: 10.1177/036354659202000604

- Martens MA, Hansen L, Mulier JC. Adductor tendinitis and musculus rectus abdominis tendopathy. Am J Sports Med. 1987 Jul-Aug;15(4):353-6. doi: 10.1177/036354658701500410

- Anderson K, Strickland SM, Warren R. Hip and groin injuries in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2001 Jul-Aug;29(4):521-33. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290042501

- Tyler TF, Nicholas SJ, Campbell RJ, Donellan S, McHugh MP. The effectiveness of a preseason exercise program to prevent adductor muscle strains in professional ice hockey players. Am J Sports Med. 2002 Sep-Oct;30(5):680-3. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300050801

- Meyers WC, Ricciardi R, Busconi BD, Waite RJ, Garrett WE Groin Pain in the Athlete. In: Arendt EA, ed. Orthopaedic Knowledge Update Sports Medicine 2. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; 1999:281–289.

- Delmore RJ, Laudner KG, Torry MR. Adductor longus activation during common hip exercises. J Sport Rehabil. 2014 May. 23 (2):79-87.

- Neuhaus P, Gabriel T, Maurer W. [Adductor insertion tendopathy, operative therapy and results]. Helv Chir Acta. 1983 Jan. 49(5):667-70

- Martens MA, Hansen L, Mulier JC. Adductor tendinitis and musculus rectus abdominis tendopathy. Am J Sports Med. 1987 Jul-Aug. 15(4):353-6.

- Schlegel TF, Bushnell BD, Godfrey J, et al. Success of nonoperative management of adductor longus tendon ruptures in National Football League athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2009 Jul. 37(7):1394-9.

- Byrne C, Alkhayat A, O’Neill P, Eustace S, Kavanagh E. Obturator internus muscle strains. Radiol Case Rep. 2017 Mar;12(1):130-132.

- Adductor Strain. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/307308-overview

- Renstrom P, Peterson L. Groin injuries in athletes. Br J Sports Med. 1980 Mar. 14(1):30-6.

- Renström P, Peterson L. Groin injuries in athletes. Br J Sports Med. 1980 Mar;14(1):30-6. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.14.1.30

- Serner A, Tol JL, Jomaah N, Weir A, Whiteley R, Thorborg K, Robinson M, Hölmich P. Diagnosis of Acute Groin Injuries: A Prospective Study of 110 Athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2015 Aug;43(8):1857-64. doi: 10.1177/0363546515585123