Hereditary coproporphyria

Hereditary coproporphyria is a rare inherited form of liver (hepatic) porphyria, caused by deficiency of the enzyme coproporphyrinogen oxidase (CPOX) and is characterized by neurological symptoms in the form of episodes (acute attacks) of stomach pain, nausea, vomiting, weakness, numbness, and pain in the hands and feet (neuropathy) 1. The porphyrias are a group of blood conditions caused by a lack of an enzyme in the body that makes heme, an important molecule that carries oxygen throughout the body and is vital for all of the body’s organs 2. The coproporphyrinogen oxidase (CPOX) enzyme deficiency results in the accumulation of porphyrin precursors in the body. Symptoms usually begin around 20-30 years of age, but have been reported at younger ages. Signs and symptoms present during the attacks may include body pain, nausea and vomiting, increased heart rate (tachycardia) and high blood pressure 1. Less common symptoms include seizures, skin lesions, and paralysis of the arms and legs, body trunk, and respiratory muscles. Most individuals with hereditary coproporphyria do not have any signs or symptoms between attacks 3.

Hereditary coproporphyria is caused by mutations in the CPOX gene and the CPOX mutation is inherited in an autosomal dominant manner. However, the enzyme coproporphyrinogen oxidase deficiency by itself is not sufficient to produce symptoms of the disease and most individuals with a CPOX gene mutation do not develop symptoms of hereditary coproporphyria. Additional factors such as endocrine factors (e.g. hormonal changes), the use of certain drugs, excess alcohol consumption, infections, and fasting or dietary changes are required to trigger the appearance of symptoms 2. Some affected individuals experience acute attacks or episodes that develop over a period of days. The course and severity of attacks is highly variable from one person to another. In some cases, particularly those without proper diagnosis and treatment, the disorder can cause life-threatening complications.

Diagnosis is based on the symptoms and specific blood, urine and stool testing. Treatment is based on preventing the symptoms. An acute attack requires hospitalization, medications, and treatment with heme therapy 4.

Hereditary coproporphyria is rare. The exact incidence is unknown. One study suggested that about 1/5,000,000 people have hereditary coproporphyria in Europe 5. Females are more commonly affected than males. Because hereditary coproporphyria is often misdiagnosed and many people who have CPOX mutations do not have symptoms, the incidence of hereditary coproporphyria may be higher.

Hereditary coproporphyria causes

Hereditary coproporphyria is caused by a genetic change (mutation) in the CPOX gene. However, having a CPOX gene mutation alone does not cause symptoms. Additional factors such as hormonal changes, specific drugs, excess alcohol, fasting are needed to trigger an attack and the appearance of symptoms. Some people with CPOX gene mutations never have symptoms of hereditary coproporphyria 1.

The American Porphyria Foundation offers a drug database (https://porphyriafoundation.org/drugdatabase/drug-safety-database-search) with safety information about the interaction of specific drugs in patients with porphyria.

Hereditary coproporphyria inheritance pattern

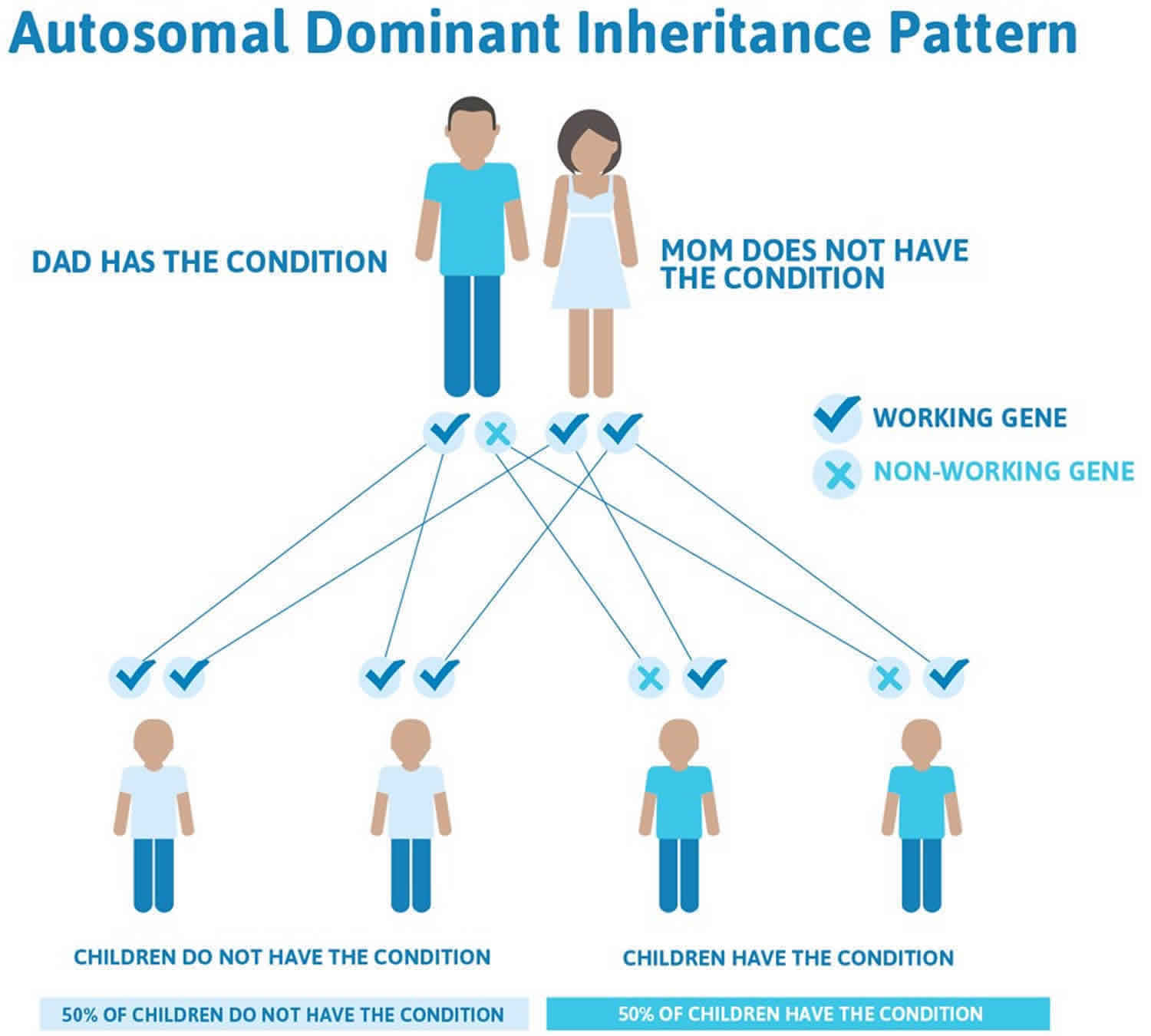

Hereditary coproporphyria is inherited in an autosomal dominant pattern 1. All individuals inherit two copies of each gene. In autosomal dominant conditions, having a mutation in just one copy of the CPOX gene causes the person to have hereditary coproporphyria. The mutation can be inherited from either parent. Some people are born with hereditary coproporphyria due to a new genetic mutation (de novo) and do not have a history of this condition in their family. There is nothing either parent can do, before or during pregnancy, to cause a child to have this.

Each child of an individual with an autosomal dominant condition has a 50% or 1 in 2 chance of inheriting the mutation and the condition. Offspring who inherit the mutation may develop hereditary coproporphyria, although they could be more or less severely affected than their parent. Sometimes a person may have a CPOX gene mutation for hereditary coproporphyria and show no signs or symptoms of it.

Often autosomal dominant conditions can be seen in multiple generations within the family. If one looks back through their family history they notice their mother, grandfather, aunt/uncle, etc., all had the same condition. In cases where the autosomal dominant condition does run in the family, the chance for an affected person to have a child with the same condition is 50% regardless of whether it is a boy or a girl. These possible outcomes occur randomly. The chance remains the same in every pregnancy and is the same for boys and girls.

- When one parent has the abnormal gene, they will pass on either their normal gene or their abnormal gene to their child. Each of their children therefore has a 50% (1 in 2) chance of inheriting the changed gene and being affected by the condition.

- There is also a 50% (1 in 2) chance that a child will inherit the normal copy of the gene. If this happens the child will not be affected by the disorder and cannot pass it on to any of his or her children.

There are cases of autosomal dominant gene changes, or mutations, where no one in the family has it before and it appears to be a new thing in the family. This is called a de novo mutation. For the individual with the condition, the chance of their children inheriting it will be 50%. However, other family members are generally not likely to be at increased risk.

Figure 1 illustrates autosomal dominant inheritance. The example below shows what happens when dad has the condition, but the chances of having a child with the condition would be the same if mom had the condition.

Figure 1. Hereditary coproporphyria autosomal dominant inheritance pattern

People with specific questions about genetic risks or genetic testing for themselves or family members should speak with a genetics professional.

Resources for locating a genetics professional in your community are available online:

- The National Society of Genetic Counselors (https://www.findageneticcounselor.com/) offers a searchable directory of genetic counselors in the United States and Canada. You can search by location, name, area of practice/specialization, and/or ZIP Code.

- The American Board of Genetic Counseling (https://www.abgc.net/about-genetic-counseling/find-a-certified-counselor/) provides a searchable directory of certified genetic counselors worldwide. You can search by practice area, name, organization, or location.

- The Canadian Association of Genetic Counselors (https://www.cagc-accg.ca/index.php?page=225) has a searchable directory of genetic counselors in Canada. You can search by name, distance from an address, province, or services.

- The American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (http://www.acmg.net/ACMG/Genetic_Services_Directory_Search.aspx) has a searchable database of medical genetics clinic services in the United States.

Hereditary coproporphyria symptoms

The symptoms of hereditary coproporphyria may be different from person to person. Some people may be more severely affected than others and not everyone with hereditary coproporphyria will have the same symptoms. Many individuals with a CPOX gene mutation do not experience any symptoms of hereditary coproporphyria 3.

In people with hereditary coproporphyria, additional factors; such as hormonal changes, certain drugs, excess alcohol consumption, infections, and fasting or dietary changes; may trigger the appearance of symptoms. Symptoms appear as acute attacks or episodes that develop over a period of days. The timing and severity of attacks vary from one person to another 2.

The symptoms of an acute attack include 1:

- Severe stomach pain leading to nausea and vomiting

- Back and leg pain

- High blood pressure

- Rapid heartbeat (tachycardia)

- Seizures (less common)

- Weakness, numbness in the arms and legs (peripheral neuropathy)

- Skin findings (in about 20% of people with hereditary coproporphyria)

- extreme sensitivity to sunlight (photosensitivity)

- fragile skin

In between attacks, people with hereditary coproporphyria are often symptom-free.

The episodes or “attacks” that characterize hereditary coproporphyria usually develop over the course of several hours or a few days. Affected individuals usually recover from an attack within days. However, if an acute attack is not diagnosed and treated promptly recovery can take much longer, even weeks or months. Most affected individuals do not exhibit any symptoms in between episodes. Onset of attacks usually occurs in the 20s or 30s, but may occur at or just after puberty. Onset before puberty is extremely rare. Attacks are more common in women than men.

Intermittent, recurrent body pain, usually affecting the abdomen and the lower back may occur chronically. Pain in these areas is often the initial sign of an attack. Pain usually begins as low-grade, vague pain in the abdomen and slowly over a few days worsens eventually causing severe abdominal pain. Pain may radiate to affect the lower back, neck, buttocks, or arms and legs. Pain is usually not well localized, but in some cases can be mistaken for inflammation of the gallbladder, appendix or another intra-abdominal organ. In a minority of cases, pain primarily affects the back and the arms and legs and is usually described as deep and aching. Abdominal pain is often described as colicky and is usually associated with nausea and vomiting. Vomiting may be severe enough that affected individuals vomit after eating or drinking any food or liquid. The absence of bowel sounds (ileus), which indicates a lack of intestinal activity may be noted. Constipation may also occur and can be severe (obstipation). Affected individuals may also experience a faster than normal heart rate (tachycardia), high blood pressure (hypertension), irregular heartbeats (cardiac arrhythmias), and a sudden fall in blood pressure upon standing (orthostatic hypotension). Hypertension may persist in between acute attacks.

Neurologic symptoms, including seizures, may be associated with hereditary coproporphyria. In some cases, new-onset seizures may be the initial sign of the disorder. Abnormally low sodium levels in the blood (hyponatremia) may occur during an attack and contribute to the onset of seizures. Affected individuals may also develop damage to the nerves in the extremities (peripheral neuropathy). Peripheral neuropathy may be preceded by the loss of deep tendon reflexes. Peripheral neuropathy is characterized by numbness or tingling and burning sensations that, in hereditary coproporphyria, usually begin in the upper legs and arms. Affected individuals may develop muscle weakness initially in the feet and legs that progresses to affect and paralyze all extremities and the body trunk (motor paralysis) and the respiratory muscles (respiratory paralysis and failure).

This ascending paralysis in hereditary coproporphyria can mimic the ascending paralysis seen in Guillain-Barre syndrome, a disorder in which the body’s immune system attacks the nerves. Differentiating hereditary coproporphyria from Guillain-Barre syndrome is extremely important to ensure prompt treatment of hereditary coproporphyria and the avoidance of medications that can precipitate or worsen an acute attack.

Some individuals develop psychological symptoms, although such symptoms are highly variable. Such symptoms can include irritability, depression, anxiety, and insomnia. Less often, more acute psychiatric symptoms can develop including hallucinations, paranoia, disorientation, mental confusion, delirium, and psychosis.

In some cases, affected individuals may develop skin (cutaneous) lesions affecting the sun-exposed areas of skin such as the hands and face. Affected individuals may develop severe pain, burning, and itching of such areas (photosensitivity). Eventually, the skin may become fragile and develop fluid-filled blisters (bullae). Affected areas may also exhibit darkly discolored (hyperpigmented) scars and excessive hair growth.

Hereditary coproporphyria diagnosis

The diagnosis of hereditary coproporphyria is suspected first based on the characteristic clinical signs and symptoms, usually during an acute attack. The observation of reddish brown urine that is free of blood is indicative, but not conclusive, of an acute porphyria. The intolerance of medications such as oral contraceptives is also suggestive of an acute porphyria. Once a person is suspected of having hereditary coproporphyria, examination of urine, blood, and stool (fecal) samples is typically done. These lab tests are usually done at the time of the acute attack and look for elevated levels of compounds found to be associated with several different types of porphyria 1.

Screening tests can help diagnose hereditary coproporphyria by measuring the levels of certain porphyrin precursors (e.g. porphobilinogen [PBG] and delta-aminolevulinic acid [ALA] in the urine. Acute attacks are always accompanied by markedly increased excretion of porphobilinogen. During a potential acute attack in an individual suspected of an acute porphyria, a random (spot) urine sample can be tested. If urinary porphobilinogen is sufficiently increased, then a qualitative 24-hour urine analysis for both porphobilinogen and delta-aminolevulinic acid should be performed and compared to urine sample results from when the individual did not exhibit symptoms. Although porphobilinogen and delta-aminolevulinic acid may be increased during an acute attack, they return to normal on recovery.

Individuals with hereditary coproporphyria may have elevated porphyrin levels such as coproporphyrin in the urine, but this finding is nonspecific (e.g. it can also be associated with other conditions) and therefore does not conclusively confirm a diagnosis of hereditary coproporphyria.

Further testing is necessary to exclude hereditary coproporphyria from variegate porphyria or acute intermittent porphyria. Fecal coproporphyrin analysis can be extremely helpful in obtaining the diagnosis. This test can reveal markedly increased levels of coproporphyrin in stool samples, which is characteristic of hereditary coproporphyria.

To identify the specific type of porphyria an individual has, molecular genetic testing can be performed to look for mutations in the CPOX gene 1. Family members of an individual positive for a CPOX mutation can be offered testing for this mutation. Molecular genetic testing is available in certain laboratories specializing in porphyria diagnosis.

At least one study suggesting diagnostic criteria for the acute dominantly inherited forms of porphyria has been published 6.

Individuals and family members who have inherited hereditary coproporphyria should be counseled on how to limit their risk of any future acute attacks. This should include information about hereditary coproporphyria and what causes attacks, how to check if a prescribed medication is safe or unsafe, and details of relevant patient support groups. Membership in the American Porphyria Foundation is very helpful to affected individuals.

Hereditary coproporphyria treatment

There is no specific treatment for hereditary coproporphyria. Treatment is aimed at managing the symptoms of hereditary coproporphyria that occur during an acute attack. Hospitalization is often necessary for acute attacks, and medications for pain, nausea and vomiting, and close observation are generally required. Initial treatment steps include stopping any medications that can potentially worsen hereditary coproporphyria or cause an attack. All triggering factors should be identified, if possible, and discontinued. In addition, ensuring proper intake of carbohydrate, either orally or intravenously, is essential. Wearing a Medic Alert bracelet or the use of a wallet card is advisable in individuals who have hereditary coproporphyria.

Some attacks may be managed by giving the person a large amount of glucose or other carbohydrates. More severe attacks are treated with heme therapy, given through a vein (intravenously). Panhematin® (hemin for injection), an enzyme inhibitor derived from red blood cells that is potent in suppressing acute attacks of porphyria, is currently the only commercially available heme therapy for treatment and prevention of acute porphyria attacks in the United States. Heme arginate (Normosang®), which is marketed in some other countries, is another type of heme therapy 4. Panhematin® (hemin for injection) almost always returns porphyrin and porphyrin precursor levels to normal values. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) originally approved panhematin for the treatment of recurrent attacks of Acute Intermittent Porphyria related to the menstrual cycle in susceptible women. Numerous symptoms including pain, hypertension, tachycardia and altered mental status, and neurologic signs have improved in individuals with acute porphyria after treatment with panhematin. Because of its potency, it is usually given after a trial of high-dose carbohydrate of any sort, including glucose therapy and should be administered only by physicians experienced in the management of porphyrias in a hospital setting.

Some individuals who experience recurrent attacks may benefit from chronic hematin infusion. This is sometimes recommended for women with severe symptoms during the time of their menses.

Attacks can also be avoided by avoiding the ‘trigger’ for the attack. The trigger can be different for different people. Triggers include certain medications, alcohol, dieting, and hormonal changes in the body. Sometimes, however, the trigger is unknown. If the person with hereditary coproporphyria has skin symptoms, avoiding excess sun exposure can reduce the blisters and skin lesions 7.

Treatment for hereditary coproporphyria may also include drugs to treat specific symptoms such as certain pain medications (analgesics), anti-anxiety drugs, anti-hypertensive drugs, and drugs to treat nausea and vomiting, tachycardia, or restlessness. Medications to treat any infections that may occur at the same time as an attack (intercurrent infection) may also be necessary. Seizures may require treatment with anti-seizure (anti-convulsant) medications, but many of the common options can worsen an attack and are contraindicated. A short-acting benzodiazepine or magnesium may be recommended. Gabapentin and propofol are considered effective and safe for prolonged control of seizures.

Although many types of drugs are believed to be safe in individuals with hereditary coproporphyria, recommendations about drugs for treating hereditary coproporphyria are based upon experience and clinical study. Since many commonly used drugs have not been tested for their effects on porphyria, they should be avoided if at all possible. If a question of drug safety arises, a physician or medical center specializing in porphyria should be contacted. The American Porphyria Foundation offers a drug database (https://porphyriafoundation.org/drugdatabase/drug-safety-database-search) with safety information about the interaction of specific drugs in patients with porphyria.

Additional treatment for individuals undergoing an attack includes monitoring for muscle weakness and respiratory issues and monitoring fluid and electrolyte balances. For example, if affected individuals develop hyponatremia, which can induce seizures, they should be treated by restricting the intake of water (water deprivation). If serum sodium is decreased severely, e.g. from normal (>134 meq/dl) to very low (100-115 meq/dl), then saline infusion is indicated.

Premenstrual attacks often resolve quickly with the onset of menstruation. Hormone manipulation may be effective in preventing such attacks. Some affected women have been treated with gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues to suppress ovulation and prevent frequent cyclic attacks.

In some cases, an attack is precipitated by a low intake of carbohydrates in an attempt to lose weight. Consequently, dietary counseling is very important. Affected individuals who are prone to attacks should eat a normal carbohydrate diet and should not greatly restrict their intake of carbohydrates or calories, even for short periods of time. If weight loss is desired, it is advisable to contact a physician and dietitian.

In individuals who develop skin complications, avoidance of sunlight will be of benefit and can include the use of double layers of clothing, long sleeves, wide brimmed hats, gloves, and sunglasses. Topical sunscreens are generally ineffective. Affected individuals will also benefit from window tinting and the use of vinyl or films to cover the windows of their homes and cars. Avoidance of sunlight can potentially cause vitamin D deficiency and some individuals may require supplemental vitamin D.

A liver transplant has been used to treat some individuals with acute forms of porphyria, specifically individuals with severe disease who have failed to respond to other treatment options. A liver transplant in individuals with hereditary coproporphyria is an option of last resort.

Hereditary coproporphyria diet

In some cases, an attack is precipitated by a low intake of carbohydrates in an attempt to lose weight. Consequently, dietary counseling is very important. Affected individuals who are prone to attacks should eat a normal carbohydrate diet and should not greatly restrict their intake of carbohydrates or calories, even for short periods of time. If weight loss is desired, it is advisable to contact a physician and dietitian.

Because glucose is used to treat acute attacks, its use in preventing attacks has been suggested and is in fact touted in lay discussions of porphyria; however, there is no evidence that heterozygotes can protect themselves by overeating or adopting a high-carbohydrate diet, and they risk becoming obese 1. Heterozygotes should adhere to a healthful diet with the usual balance of protein, fat, and carbohydrate. Weight loss is possible but only by incremental restriction of calories combined with exercise. Extreme diets (e.g., all bacon, all brown rice, starvation) are risky and should be avoided.

Pregnancy management

The effect of pregnancy on inducing acute attacks is unpredictable. In general, serious problems during pregnancy are unusual. In fact, some women with recurrent symptoms associated with the menstrual cycle report improvement during pregnancy. Attacks, if they occur, are usually in the first trimester. The women most at risk are those with hyperemesis gravidarum and inadequate caloric intake 8. Among antiemetics, ondansetron is not expected to precipitate or exacerbate acute attacks, although several studies have suggested that ondansetron exposure in the first trimester of pregnancy could lead to an increased risk of cleft palate and/or congenital heart defects in the fetus. These suggested risks have not been confirmed. However, metoclopramide should be avoided, as it may precipitate acute attacks 9.

The experience with administration of hematin (or heme arginate, which is not available in the US) during pregnancy is limited. Badminton and Deybach 10 published an anecdotal report of successful heme arginate treatment (without adverse fetal effect) in several women experiencing attacks of variegate porphyria or other acute porphyrias during pregnancy. Based on the absence of reported adverse effects, use of hematin to control exacerbations of acute intermittent porphyria during pregnancy has been recommended 11.

Prenatal testing and preimplantation genetic diagnosis

Once the CPOX pathogenic variant has been identified in an affected family member, prenatal testing for a pregnancy at increased risk and preimplantation genetic diagnosis for hereditary coproporphyria are possible.

Differences in perspective may exist among medical professionals and within families regarding the use of prenatal testing, particularly if the purpose is pregnancy termination rather than early diagnosis. While most centers would consider decisions regarding prenatal testing to be the choice of the parents, discussion of these issues is appropriate. Parents are encouraged to seek genetic counseling before reaching a decision on the use of prenatal testing.

Note: The presence of a CPOX pathogenic variant detected by prenatal testing does not predict whether individuals will be symptomatic, or if they are, what the severity of the clinical manifestations will be. It is common for the offspring who inherit the CPOX pathogenic variant from a severely affected individual to be completely asymptomatic.

Hereditary coproporphyria life expectancy

Most patients (60-80%) with hereditary coproporphyria who have an acute attack of porphyria never have another. Avoiding precipitating factors also helps prevent attacks. Researchers consider coproporphyria a less severe disease than Acute Intermittent Porphyria.

The long term outlook for people with hereditary coproporphyria varies with the severity of the symptoms. With early diagnosis and treatment, hereditary coproporphyria is rarely life-threatening. Some people with hereditary coproporphyria may have long-term pain and may be at increased risk for liver and kidney disease 1.

References- Wang B, Bissell DM. Hereditary Coproporphyria. 2012 Dec 13 [Updated 2018 Nov 8]. In: Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, et al., editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993-2020. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK114807

- Hereditary coproporphyria. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/hereditary-coproporphyria

- Wang B, Rudnick S, Cengia B, Bonkovsky HL. Acute Hepatic Porphyrias: Review and Recent Progress. Hepatol Commun. 2018;3(2):193–206. Published 2018 Dec 20. doi:10.1002/hep4.1297 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6357830

- Balwani M, Wang B, Anderson KE, Bloomer JR, Bissell DM, Bonkovsky HL, Phillips JD, Desnick RJ, et al.. Acute hepatic porphyrias: recommendations for evaluation and long-term management. Hepatology. 2017; 66:1314-1322. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28605040

- Elder G1, Harper P, Badminton M, Sandberg S, Deybach JC. The incidence of inherited porphyrias in Europe. J Inherit Metab Dis. Sep 2013; 36(5):849-57. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23114748

- Whatley SD, Mason NG, Woolf JR, Newcombe RG, Elder GH, Badminton MN. Diagnostic strategies for autosomal dominant acute porphyrias: retrospective analysis of 467 unrelated patients referred for mutational analysis of the HMBS, CPOX, or PPOX gene. Clin Chem. 2009; 55:1406-1414. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19460837

- Stein PE, Badminton MN, Rees DC.. Update review of the acute porphyrias. Br Jl Hemot. 2017; 176(4):527-538. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27982422

- Aggarwal N, Bagga R, Sawhney H, Suri V, Vasishta K. Pregnancy with acute intermittent porphyria: a case report and review of literature. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2002;28:160–2.

- Shenhav S, Gemer O, Sassoon E, Segal S. Acute intermittent porphyria precipitated by hyperemesis and metoclopramide treatment in pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1997;76:484–5.

- Badminton MN, Deybach JC. Treatment of an acute attack of porphyria during pregnancy. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:668–9.

- Farfaras A, Zagouri F, Zografos G, Kostopoulou A, Sergentanis TN, Antoniou S. Acute intermittent porphyria in pregnancy: a common misdiagnosis. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 2010;37:256–60.