What is Bloating

Abdominal bloating is a condition in which your belly (abdomen) feels full and tight. Your belly may look swollen (distended). Bloating is defined as subjective discomfort by patient’s sensation of intestinal gas or a feeling of pressure or being distended without obvious visible distension; whereas, abdominal distension is a visible or measurable increase in abdominal size (abdominal girth) 1. Patients also describe a sense of fullness or pressure, which can occur anywhere in the abdomen (epigastric, mid, lower, or throughout). People often describe abdominal symptoms as bloating, especially if those symptoms don’t seem to be relieved by belching (also known as burping), passing gas or having a bowel movement. The exact connection between intestinal gas and bloating is not fully understood. Many people with bloating symptoms don’t have any more gas in their intestine than do other people. Many people, particularly those with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or anxiety, may have a greater sensitivity to abdominal symptoms and intestinal gas, rather than an excess amount. Nonetheless, bloating may be relieved by the behavioral changes that reduce belching, or the dietary changes that reduce flatus (intestinal gas that is passed from the anus).

Abdominal bloating is characterized by the subjective symptoms of trapped gas, abdominal pressure, and fullness. In contrast, abdominal distension reflects an objective physical transition of abdominal girth. Patients commonly describe how they look “like a balloon” or “like I’m pregnant.” Abdominal distension and abdominal bloating don’t always go hand in hand. Only about 50%-60% of patients with bloating report abdominal distension (visible or measurable increase in abdominal size), thus highlighting the distinct nature of these disorders 2. Bloating is one of the most common gastrointestinal symptoms, which is a frequent complaint in the patients of all ages 3. Patients with symptoms of gas, bloating, and burping (belching or getting rid of excess air from your upper digestive tract) are often attributable to one or more of the functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs), including functional dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and chronic idiopathic constipation; as well as in patients with organic disorders (e.g. ovarian cancer, colon cancer), but bloating may appear alone 3, 4. Approximately 75% of patients with bloating report their symptoms as moderate to severe, and 50% say that this causes a reduction in their ability to have daily activities of normal function. Many clinicians encounter the patients’ complaints such as “too much gas in abdomen,” “heavy and uncomfortable feeling in abdomen” and “full belly.” Burping and belching, which are other common gastrointestinal complaints, reflect the expulsion of excess gas from the stomach. These complaints may or may not be related to bloating and abdominal distension. The severity of bloating is varied from mild discomfort to severe, and it is one of the bothersome symptoms of the patients, affecting their quality of life. Despite being one of the frequent and bothersome complaints, bloating remains incompletely understood of all the symptoms 4.

In the medical literature, the terms “bloating” and “distension” are largely used synonymously, relying more on patient descriptions rather than on any attempt to record an actual change in girth. However, it has recently been suggested that the term “bloating” should be reserved exclusively for the subjective symptom of abdominal enlargement, with the term “distension” being used only when there is an actual change in girth. The situation is further complicated by the fact that in some languages there is not necessarily an exact equivalent of the word “bloating” 5.

In the past, bloating had been considered to be related to abdominal distension directly, but recent studies have suggested that it is not always accompanied by abdominal distension (increase in abdominal size) 6. There have been many studies to evaluate the relationship between bloating and abdominal distension. One study has shown that actual abdominal distension only occurred in about half of the patients suffering from bloating 7. In addition, some patients with both visceral hypersensitivity and functional gastrointestinal disorders complained of bloating in the absence of visible distension 8, 9.

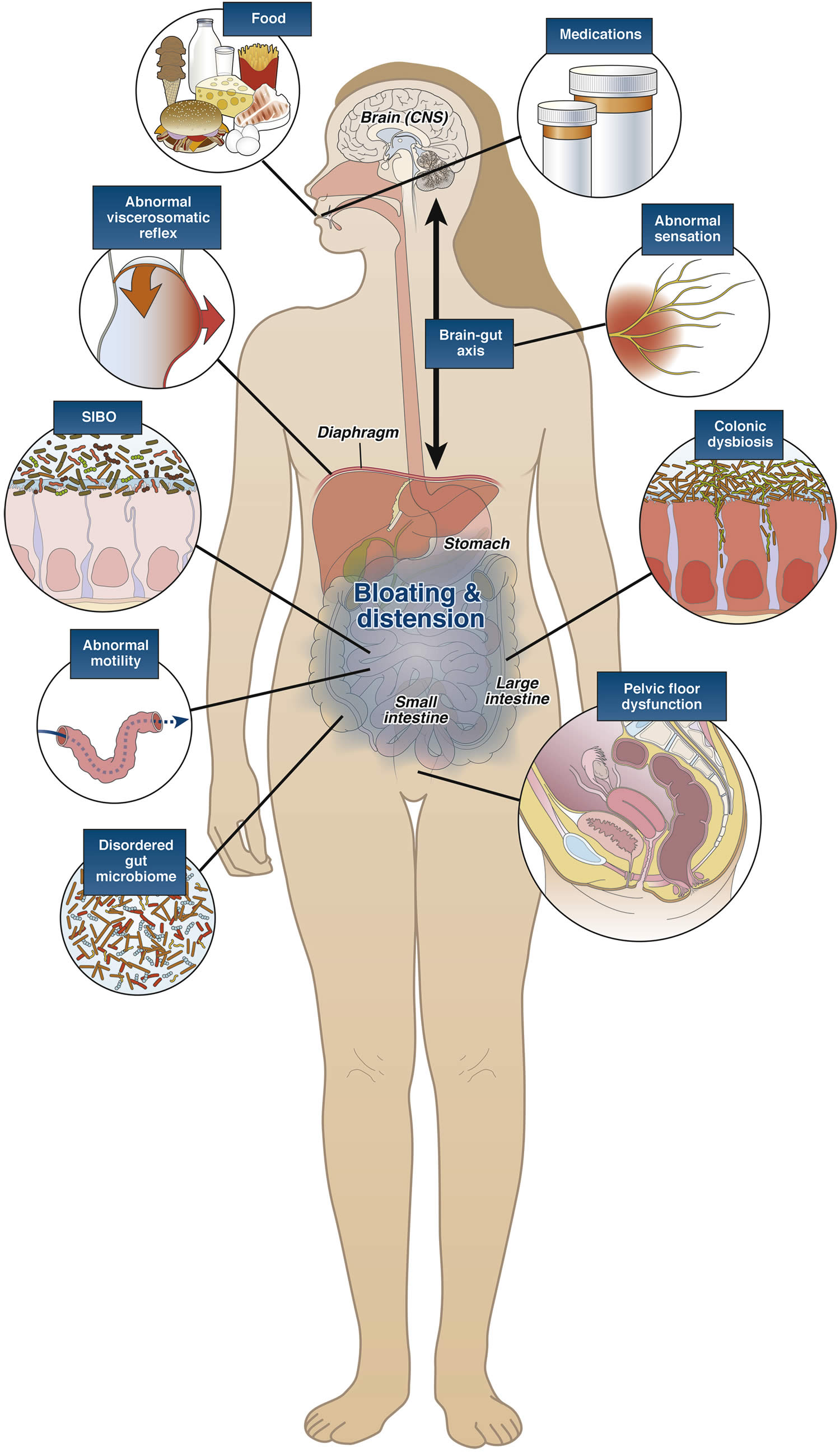

When it comes to the underlying pathophysiology, most patients believe their symptoms are caused by their body making too much gas. This is true in only a minority of patients. Abdominal bloating not caused by an increase in gas so much as it is an increase in sensation. The major pathophysiologic contributors to these conditions are small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) as well as carbohydrate intolerance, the latter of which is particularly influenced by lactose and fructose intolerance. Lactase deficiency by itself does not necessarily cause malabsorption and not all individuals who are lactase deficient become symptomatic after ingesting lactose. Instead, symptom generation in some patients may require additional factors such as genetic predisposition or visceral hypersensitivity.

Symptoms occurring within 30 minutes after eating or the inability to finish a meal are attributable to upper gastrointestinal disorders, usually functional dyspepsia. Other conditions, including gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), Helicobacter pylori infection, gastroparesis, impaired gastric accommodation, and gastric outlet obstruction, must also be considered 10.

Abdominal bloating pathogenesis may also be influenced by an altered microbiome (microbiome consists of microbes that are both helpful and potentially harmful), which is an effect being seen across almost all disease states. The role of the gut microbiome in causing changes in gastrointestinal (GI) motility, sensation, or permeability has a profound effect in producing these symptoms of abdominal bloating and distension.

Abdominal bloating is common in patients with abnormal gastrointestinal motility. Doctors see this particularly in patients with gastroparesis (a disease in which the stomach cannot empty itself of food in a normal fashion), in whom the prevalence can be in the range of 50% or more.

It’s similar in patients with pelvic floor dysfunction. Such patients with established anorectal motor dysfunction can have problems in evacuating flatus and stool. Pelvic outlet obstruction can also contribute to increased delays in colonic transit.

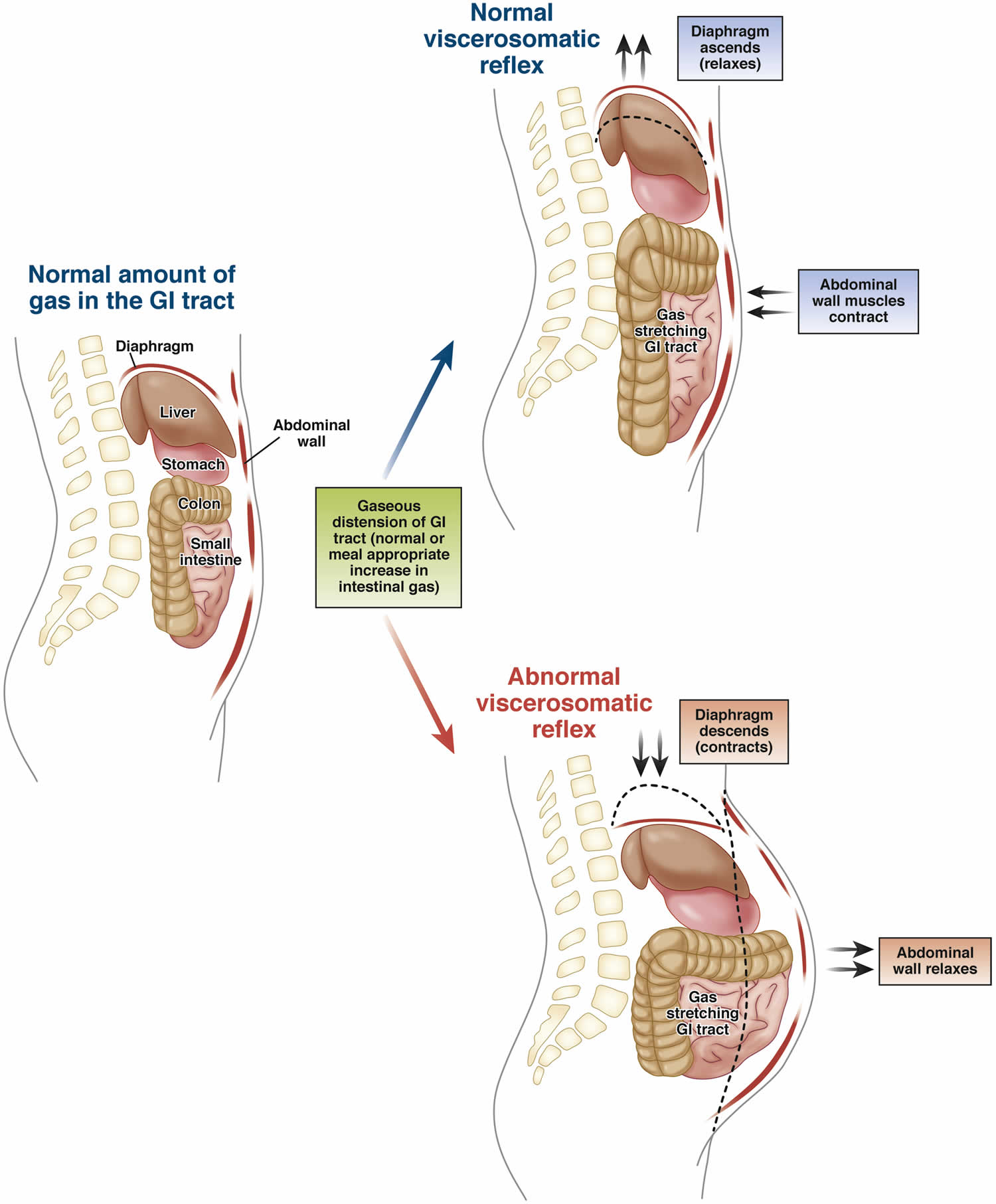

Another associated syndrome is called abdomino-phrenic dyssynergia 11. This is a paradoxical response whereby the diaphragm contracts when pushing things down and the abdominal wall relaxes. What you would normally expect to see is the abdominal muscles contract and the diaphragm relaxes in order to maintain the integrity of the craniocaudal capacity to avoid distension. Reversing this can lead to the symptoms of bloating and abdominal distension.

There’s also another cause for visceral hypersensitivity. This can be magnified by both complex brain-gut neural interactions and factors such as anxiety, depression, somatization, and hypervigilance. A lot of these conditions are also impacted by sleep. Sensory thresholds are all lowered in the presence of sleep fragmentation, which in turn heightens visceral hypersensitivity.

Patients with chronic functional bloating and distension may be diagnosed using the Rome criteria.

Rome criteria for functional abdominal bloating and/or distension include 12:

- Recurrent bloating and/or distention occurring at least 1 day/week on average;

- Bloating and distension should be the predominant gastrointestinal symptom;

- Patients should not meet criteria for irritable bowel syndrome, functional constipation, functional diarrhea, or postprandial distress syndrome;

- Symptom onset should have occurred at least 6 months prior to diagnosis;

- Symptoms should be active within the preceding 3 months.

Note: Neither symptom is required to be present for a patient to meet Rome criteria for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or functional constipation although bloating and distension are frequently present in both disorders and are noted as supporting criteria.

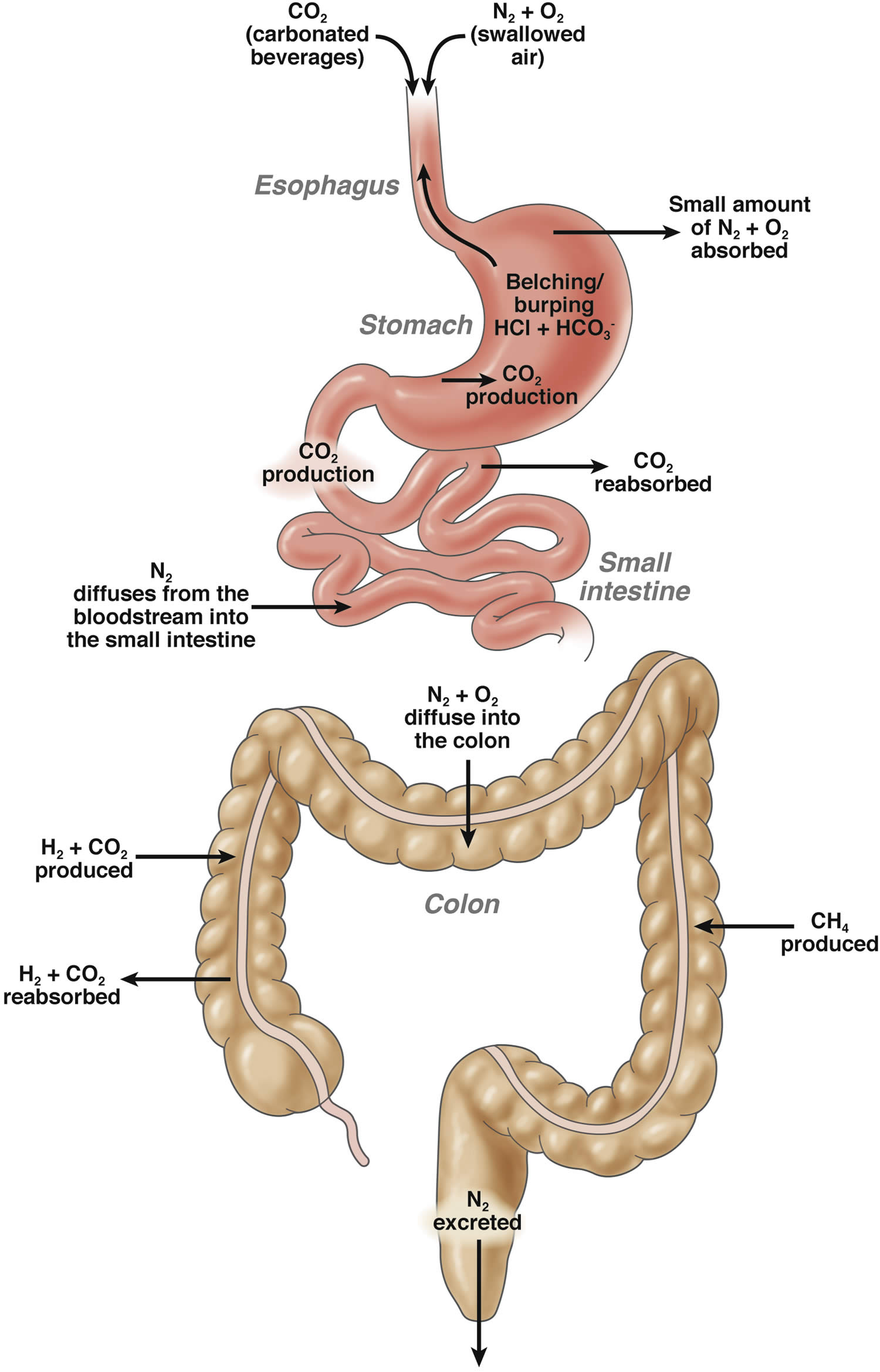

Figure 1. Normal gastrointestinal tract gas production, absorption and excretion

Abbreviations: CO2 = carbon dioxide; N2 = nitrogen; O2 = oxygen; NH4 = methane

[Source 13 ]Figure 2. Pathophysiology of bloating and gas

[Source 13 ]In summary, abdominal bloating is the subjective symptom and distension (increase in abdominal size) is the objective sign, so bloating and distension should be considered as separate disorders with different mechanisms. Although bloating has been considered as a supportive symptom for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or functional bloating according to Rome criteria, functional bloating is also included as an independent entity in Rome criteria 14, 15, 16. The diagnosis of functional bloating is made in patients who do not meet the diagnostic criteria of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) or other functional gastrointestinal disorders, but have recurrent symptoms of bloating. According to Rome III, the diagnostic criteria include recurrent feeling of bloating or visible distension at least 3 days a month in the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis. Also it should exclude functional dyspepsia, IBS (irritable bowel syndrome) or other functional gastrointestinal disorders.

Intestinal symptoms can be embarrassing — but don’t let embarrassment keep you from seeking help. Excessive belching, passing gas and bloating often resolve on their own or with simple changes. If these are the only symptoms you have, they rarely represent any serious underlying condition.

See your doctor if your symptoms don’t improve with simple changes, particularly if you also notice:

- Persistent or severe abdominal pain

- Blood in the stools or dark, tarry looking stools

- Changes in the color or frequency of stools

- Diarrhea

- Heartburn that is getting worse

- Chest discomfort

- Vomiting

- Weight loss

- Loss of appetite or feeling full quickly.

These signs and symptoms could signal an underlying digestive condition.

Seek immediate care if you experience:

- Prolonged abdominal pain

- Chest pain

For diagnosis, a detailed clinical history and physical examination is critical to understand the underlying cause of bloating and distention. Details regarding the onset and timing of bloating and distention, the relationship to food or bowel movements, a surgical history (ie, Nissen fundoplication) 17 and a careful review of medications (ie, narcotics), supplements, and dietary habits should be obtained 18. A physical examination should include a rectal examination to identify an evacuation disorder in patients with constipation 19. Information obtained will guide specific diagnostic testing.

You may take the following steps to treat bloating:

- Avoid chewing gum or carbonated drinks. Stay away from foods with high levels of fructose or sorbitol.

- Avoid foods that can produce gas, such as Brussels sprouts, turnips, cabbage, beans, and lentils.

- Do not eat too quickly.

- Stop smoking.

Get treatment for constipation if you have it. However, fiber supplements such as psyllium or 100% bran can make your symptoms worse.

You may try simethicone and other medicines you buy at the drugstore to help with gas. Charcoal caps can also help.

Watch for foods that trigger your bloating so you can start to avoid those foods. These may include:

- Milk and other dairy products that contain lactose

- Certain carbohydrates that contain fructose, known as Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols (FODMAPs).

- Abdominal mass

- Difficulty swallowing (dysphagia)

- Extreme diarrhea symptoms (large volume, bloody, nocturnal, progressive pain, does not improve with fasting)

- Fever

- Gastrointestinal bleeding (melena or hematochezia)

- Jaundice

- Enlarged or swollen lymph glands (lymphadenopathy)

- New-onset symptoms in patients 55 years and older —people do not typically develop functional gastrointestinal disorders later in life. Patients 55 years and older who report new-onset symptoms should be considered for more in-depth evaluation to exclude alternative diagnoses.

- Painful swallowing (odynophagia)

- Symptoms of chronic pancreatitis — people with recurrent episodes of acute or chronic disabling pain, especially in the setting of many years of alcohol abuse, should be considered for evaluation for chronic pancreatitis (may rarely be confused with irritable bowel syndrome, gastroparesis, or small bowel obstruction) 20

- Symptoms of gastrointestinal cancer, including family history — people with a family history of gastrointestinal malignancy, particularly pancreatic or colorectal cancer, should be considered for evaluation for gastrointestinal cancers.

- Symptoms of ovarian cancer, including family history — women 55 years and older who report new-onset bloating, increased abdominal size, difficulty eating, or early satiety with abdominal, pelvic, or back pain should be considered for evaluation for ovarian cancer 21.

- Tenesmus (rectal pain or feeling of incomplete evacuation)

- Unintentional weight loss

- Vomiting

Bloating Not To Be Confused With Belching and Flatulence

Belching

Belching = Getting rid of excess air

Belching or burping, is your body’s way of expelling excess air from your upper digestive tract. Most belching is caused by swallowing excess air. This air most often never even reaches the stomach but accumulates in the esophagus. Belching may or may not coexist with bloating and distention. Belching occurs because of an excess of swallowed air and is caused by processes often unrelated to those causing bloating 22.

You may swallow excess air if you eat or drink too fast, talk while you eat, chew gum or suck on hard candies, drink carbonated beverages, or smoke. Some people swallow air as a nervous habit — even when they’re not eating or drinking. This is called aerophagia.

Acid reflux or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) can sometimes cause excessive belching by promoting increased swallowing. Chronic belching may be related to inflammation of the stomach lining (gastritis) or to an infection with Helicobacter pylori, the bacterium responsible for some stomach ulcers. In these cases, the belching is accompanied by other symptoms, such as heartburn or abdominal pain.

You can reduce belching if you:

- Eat and drink slowly. Taking your time can help you swallow less air. Try to make meals relaxed occasions; eating when you’re stressed or on the run increases the air you swallow.

- Avoid carbonated drinks and beer. They release carbon dioxide gas.

- Skip the gum and hard candy. When you chew gum or suck on hard candy, you swallow more often than normal. Part of what you’re swallowing is air.

- Don’t smoke. When you inhale smoke, you also inhale and swallow air.

- Check your dentures. Poorly fitting dentures can cause you to swallow excess air when you eat and drink.

- Get moving. It may help to take a short walk after eating.

- Treat heartburn. For occasional, mild heartburn, over-the-counter antacids or other remedies may be helpful. GERD may require prescription-strength medication or other treatments.

Flatulence

Flatulence is the buildup of gas in the intestines and the expulsion of excess colonic gas and is usually related to diet 22. The colon (large intestine) is relatively insensitive to increased gas and distention; excess flatulence does not usually cause symptoms of bloating.

Gas in the small intestine or colon is typically caused by the digestion or fermentation of undigested food, such as plant fiber or certain sugars (carbohydrates), by bacteria found in the colon. Gas can also form when your digestive system doesn’t completely break down certain components in foods, such as gluten or the sugar in dairy products and fruit.

Other sources of intestinal gas may include:

- Food residue in your colon

- A change in the bacteria in the small intestine

- Poor absorption of carbohydrates, which can upset the balance of helpful bacteria in your digestive system

- Constipation, since the longer food waste remains in your colon, the more time it has to ferment

- A digestive disorder, such as lactose or fructose intolerance or Celiac disease.

To prevent excess gas, it may help to:

- Eliminate certain foods. Common gas-causing offenders include beans, peas, lentils, cabbage, onions, broccoli, cauliflower, whole-grain foods, mushrooms, certain fruits, and beer and other carbonated drinks. Try removing one food at a time to see if your gas improves.

- Read labels. If dairy products seem to be a problem, you may have some degree of lactose intolerance. Pay attention to what you eat and try low-lactose or lactose-free varieties. Certain indigestible carbohydrates found in sugar-free foods (sorbitol, mannitol and xylitol) also may result in increased gas.

- Eat fewer fatty foods. Fat slows digestion, giving food more time to ferment.

- Temporarily cut back on high-fiber foods. Fiber has many benefits, but many high-fiber foods are also great gas producers. After a break, slowly add fiber back to your diet.

- Try an over-the-counter remedy. Some products such as Lactaid or Dairy Ease can help digest lactose. Products containing simethicone (Gas-X, Mylanta Gas) haven’t been proved to be helpful, but many people feel that these products work. Products such as Beano may decrease the gas produced during the breakdown of certain types of beans.

How Common is Bloating?

In USA, 15-30% of general population has been reported to experience bloating 23, 24. Also in Asia, similar result has been shown (15-23%), suggesting that the prevalence of bloating is not interracially different 25. Though the data for functional bloating alone are relatively little, women typically have higher rates of bloating than men according to the reports of IBS 26. This relevance between female gender and bloating has long been suggested and the hormonal effect in connection with menstrual cycle is regarded as one of the possible explanation 27, 28. Besides, there are some reports of obese people experiencing more gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain or bloating 29, 30.

Bloating is the second most common reported symptom in patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) following abdominal pain 31. In a study from USA which assessed bloating in 542 Irritable Bowel Syndrome patients, 76% of the patients reported that they experienced bloating 32. Other study revealed that more than 90% of patients with IBS suffered from bloating 33. In addition, on comparing constipation dominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS-C) with diarrhea dominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS-D), the prevalence of bloating was higher in Irritable Bowel Syndrome-constipation 34.

A survey from the USA suggested that more than 65% of patients with bloating rated their symptom as moderate to severe, and 54% of patients complained of decreased daily activity due to bloating. Furthermore, 43% of patients took medication for bloating or needed medication 24.

What are Functional Bowel Disorders

A functional bowel disorder is a functional gastrointestinal disorder with symptoms attributable to the mid or lower gastrointestinal tract, including the irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), functional abdominal bloating, functional constipation, functional diarrhea, and unspecified functional bowel disorder 35. Subjects with a functional bowel disorder may be divided into the following groups:

- non-patients: those who have never sought health care for the functional bowel disorder;

- patients: those who have sought care for the functional bowel disorder.

Symptoms of a functional bowel disorder must have been present for 12 weeks or more within the past 12 months; the 12 weeks need not be consecutive. The diagnosis always presumes the absence of a structural or biochemical explanation for the symptoms 35.

Functional Bowel Disorders consist of:

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS)

- Functional Bloating

- Functional dyspepsia

- Functional constipation

- Functional diarrhea

- Unspecified functional bowel disorder

- Functional abdominal pain

- Functional abdominal pain syndrome

- Unspecified functional abdominal pain

Functional dyspepsia

Functional dyspepsia (nonulcer dyspepsia) is a term for recurring signs and symptoms of indigestion that have no obvious cause. Functional dyspepsia is also called nonulcer stomach pain or nonulcer dyspepsia. Functional dyspepsia is common and can be long lasting — although signs and symptoms are mostly intermittent. These signs and symptoms resemble those of an ulcer, such as pain or discomfort in your upper abdomen, often accompanied by bloating, belching and nausea.

Patients with functional dyspepsia typically report postprandial fullness, bloating, or early satiation; however, some patients with functional dyspepsia may instead report epigastric pain or burning unrelated to meals 36. In addition, some patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) may report symptoms that also occur in patients with functional dyspepsia, including nausea, vomiting, early satiety, bloating, and belching. This suggests that functional dyspepsia and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) may coexist in some patients or that others thought to have GERD may instead have functional dyspepsia 37.

The relationship between functional dyspepsia and H. pylori infection is unclear. Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) eradication results in functional dyspepsia symptom resolution in some patients. Consequently, a test-and-treat strategy (noninvasive testing for H. pylori [e.g., urea breath testing] and treatment of confirmed infection) is recommended rather than expensive and invasive tests, such as endoscopy 38.

The relationship between functional dyspepsia and acid secretion is also unclear; empiric proton pump inhibitor therapy reduces functional dyspepsia symptoms in some patients, even when acid reflux cannot be demonstrated. Therefore, a trial of antisecretory therapy is recommended for patients who are H. pylori negative or for those who remain symptomatic after H. pylori eradication 36.

Irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic, often disabling, functional bowel disorder characterized by abdominal discomfort or pain, usually with bloating or abdominal distention and changes in bowel habits and with features of disordered defecation 39. Subtypes of IBS depend on the predominant bowel habit: IBS-diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS-constipation (IBS-C), or IBS-mixed (IBS-M) 40, 41, 42. Fiber, antispasmodics, and peppermint oil are moderately effective for IBS symptoms in some patients 43. Surveys of Western populations have revealed irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) in 15–20% of adolescents and adults, with a higher prevalence in women; the prevalence is variable in other populations 44.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) has a chronic relapsing course and overlaps with other functional gastrointestinal disorders 45. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) accounts for high direct medical expenses 46 and indirect costs, including absenteeism from work 45.

The pathophysiology of Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is incompletely understood and treatment options are limited, partly due to the heterogeneity of the IBS population 47. Nearly two thirds of IBS patients report that their symptoms are related to food 48. The pathogenic mechanism by which food induces IBS symptoms remains unclear, but it includes visceral hypersensitivity, altered motility, abnormal colonic fermentation, and sugar malabsorption, all of which lead to increased gas production and luminal distension 49. The use of elimination diets for the treatment of IBS has yielded conflicting results, although this treatment option has been slightly more successful in IBS patients who have diarrhea 50. However, elimination diets can result in dietary restrictions that can be burdensome to patients and can potentially compromise their nutritional health. In addition, there is a lack of randomized controlled data that show a symptomatic benefit with elimination diets 51.

The Rome Diagnostic Criteria for Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) 52:

Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort at least 3 days per month for the past 3 months, associated with two or more of the following:

- (1) Relieved with defecation; and/or

- (2) Onset associated with a change in frequency of stool; and/or

- (3) Onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool.

The following symptoms cumulatively support the diagnosis of IBS:

- abnormal stool frequency (for research purposes “abnormal” may be defined as >3/day and <3/week);

- abnormal stool form (lumpy/hard or loose/watery stool);

- abnormal stool passage (straining, urgency,or feeling of incomplete evacuation);

- passage of mucus;

- bloating or feeling of abdominal distension.

How To Diagnose Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

[Source 53]What Causes Bloating

The cause for chronic abdominal bloating and distension is complex, often multifactorial in nature, incompletely understood and remains ambiguous. The differential diagnosis includes both organic and functional disorders. Although some evidences are emerging in support the potential mechanisms, including gut hypersensitivity, impaired gas handling, altered gut microbiota, and abnormal abdominal-phrenic reflexes 4. Most patients believe that their symptoms are due to an increased amount of “gas” within the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, although this accounts for symptoms in only a minority of patients. Computed tomography (CT) imaging has shown that luminal gas increases in only 25% of patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) during a spontaneous episode of abdominal distension or following consumption of a “high-flatulence” diet 54.

We all swallow air during the process of eating. Individuals can have excess swallowing due to sucking on hard candies or chewing gum. Drinking carbonated beverages such as soda or beer can also generate excess gastric air. In addition, individuals who experience anxiety may swallow air excessively. Poorly fitting dentures and chronic postnasal “drip” can also cause excess air swallowing. As a result, significant amounts of gas can enter the stomach and small bowel in 24 hours which can lead to belching, bloating or flatulence.

Some carbohydrates cannot be digested by the enzymes in the small intestine and reach the colon where bacteria metabolize them to hydrogen and carbon dioxide gasses. Examples of such food are bran, cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, and beans. This can result in excess flatulence in some patients. Many patients experience abdominal cramps, bloating and flatulence when they ingest milk, certain cheeses or ice cream because they lack the enzyme (lactase) which is required to digest milk sugars (lactose). This condition, called lactose intolerance, is less common in people of northern European origin.

Another cause of bloating and abdominal distension is termed bacterial overgrowth. This is not an infection, but occurs when there is an excess amount of normal bacteria in the small intestine. This results in increased production of intestinal gas contributing to the above symptoms. Finally, underlying constipation may also contribute to bloating and a sense of abdominal distention.

Abdominal bloating or abdominal distension may occur in isolation or along with other gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) (eg, aerophagia, nonulcer dyspepsia, gastroparesis, irritable bowel syndrome) or organic disorders (eg, ovarian cancer, colon cancer) 3. Gastroparesis (and consequent bloating) also has many nonfunctional causes, the most important of which is autonomic visceral neuropathy due to diabetes; other causes include postviral infection, drugs with anticholinergic properties, and long-term opiate use 3. However, excessive intestinal gas is not clearly linked to these complaints. In most healthy people, 1 L/hour of gas can be infused into the gut with minimal symptoms. It is likely that many symptoms are incorrectly attributed to “too much gas” 3.

On the other hand, some patients with recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms often cannot tolerate small quantities of gas: Retrograde colonic distension by balloon inflation or air instillation during colonoscopy often elicits severe discomfort in some patients (eg, those with irritable bowel syndrome) but minimal symptoms in others 3. Similarly, patients with eating disorders (eg, anorexia nervosa, bulimia) often misperceive and are particularly stressed by symptoms such as bloating. Thus, the basic abnormality in patients with gas-related symptoms may be a hypersensitive intestine. Altered motility may contribute further to symptoms 3.

Owing to the insufficient understanding of these mechanisms, the available therapeutic options are limited 4. However, medical treatment with some prokinetics, rifaximin, lubiprostone and linaclotide could be considered in the treatment of bloating. In addition, dietary intervention is important in relieving symptom in patients with bloating 4.

The following sections highlight major causes of bloating and distension.

Common causes of abdominal bloating include:

- Swallowing air

- Constipation

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Lactose intolerance and problems digesting other foods

- Overeating

- Small bowel bacterial overgrowth

- Weight gain

You may have bloating if you take the oral diabetes medicine acarbose. Some other medicines or foods containing lactulose or sorbitol, may cause bloating.

Gas forms in your large intestine (colon) when bacteria ferment carbohydrates — fiber, some starches and some sugars — that aren’t digested in your small intestine. Bacteria also consume some of that gas, but the remaining gas is released when you pass gas from your anus.

Dietary factors that may cause bloating, gas and flatulence

| Possible causes of functional gastrointestinal disorders | Dietary choices | Results |

| Artificial sweeteners | Sugar-free gum (especially gum containing sorbitol or mannitol) | Bloating, often with diarrhea |

| Caffeinated beverages | Coffee, soda | Can cause belching and diarrhea but less likely to cause bloating |

| Can decrease lower esophageal sphincter pressure, which causes belching | ||

| Carbonated drinks | Soda, other carbonated beverages | Excess gas and bloating |

| Eating habits | Bolting or gulping food, eating quickly, not thoroughly chewing food, routinely chewing gum | Belching, bloating, gas |

| Over-the-counter medications | Antacids containing magnesium | Diarrhea (bloating less likely) |

| Size and timing of meals | Large or frequent meals, meals eaten late in the day | Bloating with distention, dyspepsia |

| Specific foods | Beans, fiber, fructans, fructose, lactose, legumes | Gas |

Common foods that cause gas

Certain high-fiber foods may cause gas, including:

- Beans and peas (legumes)

- Fruits

- Vegetables

- Whole grains

While high-fiber foods increase gas production, fiber is essential for keeping your digestive tract in good working order and regulating blood sugar and cholesterol levels.

Other dietary factors

Other dietary factors that can contribute to increased gas in the digestive system include the following:

- Carbonated beverages, such as soda and beer, increase stomach gas.

- Eating habits, such as eating too quickly, drinking through a straw, chewing gum, sucking on candies or talking while chewing results in swallowing more air.

- Fiber supplements containing psyllium, such as Metamucil, may increase colon gas.

- Sugar substitutes or artificial sweeteners, such as sorbitol, mannitol and xylitol, found in some sugar-free foods and beverages may cause excess colon gas.

Medical conditions

Medical conditions that may increase intestinal gas, bloating or gas pain include the following:

- Chronic intestinal disease. Excess gas is often a symptom of chronic intestinal conditions, such as diverticulitis, ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease.

- Small bowel bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). An increase or change in the bacteria in the small intestine can cause excess gas, diarrhea and weight loss.

- Food intolerances. Gas or bloating may occur if your digestive system can’t break down and absorb certain foods, such as the sugar in dairy products (lactose) or proteins such as gluten in wheat and other grains.

- Lactose, fructose, and other carbohydrate intolerances

- Celiac disease

- Constipation. Constipation may make it difficult to pass gas.

- Pancreatic insufficiency – problems with the pancreas not producing enough digestive enzymes (pancreatic insufficiency)

- Ascites

- Celiac disease

- Dumping syndrome

- Ovarian cancer

- Prior gastroesophageal surgery (eg, fundoplication, bariatric surgery)

- Gastric outlet obstruction

- Gastroparesis

- Gastrointestinal or gynecologic malignancy

- Hypothyroidism

- Adiposity

- Small intestine diverticulosis

- Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction

- Disorders of gut-brain interaction

- Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- Pelvic floor dysfunction

- Functional bloating

- Functional dyspepsia

Abnormal Gut Microbiota

The gastrointestinal tract microbiota play an important role in host immune system, and there are more than 500 different species of gastrointestinal microbiota in adult, which mostly are obligate anaerobes 55. Only a fraction of these organisms can be cultured; therefore, the understanding of the functions of various microbes in the GI tract is still limited. However, researches over the past decades have shown that altered colonic flora were found in stool samples of patients with IBS 56, 57. Parkes et al. 58 suggested that the GI microbiota can be divided into 2 ecosystems; the luminal bacteria and the mucosa-associated bacteria (Figure 3). Luminal microbiota form the majority of the GI tract flora, and they play a key role in bloating and flatulence in IBS through carbohydrate fermentation and gas production 58. It has been shown that fecal microbiota are significantly altered in IBS. That is, some patients with IBS seem to have different patterns of colonization with coliforms, such as lactobacillus and bifidobacterium compared to the controls 59.

In addition, these microbial changes altered protein and carbohydrate metabolism in the gut 60. A study from Japan also showed higher counts of Veillonella and Lactobacillus in IBS patients than in controls. Besides, they expressed significantly higher levels of acetic acid, propionic acid and total organic acids than controls, which is related to symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating and changes in bowel habits 61. Another study demonstrated that the patients with IBS produced more Hydrogen gas but the total gas excretion was similar in both IBS patients and controls 62. This may be associated with alteration in colonic fermentation by hydrogen-consuming bacteria, which may be an important factor in the pathogenesis of IBS.

Collins et al. 63 have proposed that disruption of the balance between the host and intestinal microbiota produces changes in the mucosal immune system from microscopic to overt inflammation and this also results in changes in gut sensory-motor function and immune activity. Besides, these altered microflora may produce differences in fermented gas type and volume, which may be the causes of symptom in patients with bloating 63, 64.

There have been some reports to verify the relationship between the types of gas produced by colonic microflora and bloating. The low producers of methane reported significantly increased bloating and cramping after ingestion of sorbitol and fiber, and the high producers of methane revealed lower prevalence of severe lactulose intolerance than low producers. Hence, the role of methanogenic flora may be important in the pathogenesis of bloating 65, 66.

Figure 3. Luminal and mucosal colonic microbiota and their roles in gut homeostasis.

[Source 58]Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth and Carbohydrate Intolerance

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) and carbohydrate (eg, lactose and fructose) intolerance are common causes of chronic bloating and distension. Excess small intestine bacteria can cause symptoms due to carbohydrate fermentation with subsequent gas production and stretch and distension of the small intestine. Altered sensation and an abnormal viscerosomatic reflex may also play a role although these mechanisms have not been well studied in patients with SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth). Carbohydrate intolerance may cause symptoms of bloating and distension due to an increased osmotic load, excess fluid retention, and excess fermentation in the colon. The lack of consensus regarding an ideal test to diagnose SIBO makes it difficult to ascertain its true prevalence. In addition, no prospective trial has evaluated patients diagnosed solely with chronic bloating and distension to determine the prevalence of SIBO or food intolerances, and thus most data come from the best-studied functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID), IBS. A meta-analysis reported the prevalence of SIBO to be 0%–20% in healthy control subjects vs 4%–78% in patients with IBS 67. The prevalence of food intolerance, which has similar symptoms, in the general population approaches 20% 68. The true prevalence of carbohydrate intolerance is unclear as carbohydrate intolerance does not necessarily correspond with carbohydrate malabsorption by breath test. One prospective study of symptomatic patients with various functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) (n = 1372) identified a prevalence of lactose intolerance and malabsorption of 51% and 32%, respectively, and a prevalence of fructose intolerance and malabsorption of 60% and 45%, respectively 69. Lactase deficiency by itself may not cause malabsorption, as not all individuals who are lactase-deficient become symptomatic after ingesting lactose. This indicates that other factors (eg, genetic predisposition, visceral hypersensitivity) may be required for symptom generation in some patients 13.

In patients with IBS who specifically complain of bloating have been reported to have increased gas production from bacterial fermentation caused by small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO). Pimentel and colleagues had established the concept that small intestinal bacterial overgrowth might be a major pathogenesis of IBS 70, Moreover, several studies found significant improvement of symptoms such as abdominal pain or bloating, when they were treated with antibiotics 70, 71. These findings, however, have not been supported by other studies 72, 73, they found mildly increased counts of small intestinal bacteria by culture to be more common in IBS, but the breath Hydrogen gas concentration was not significantly different between IBS patients and controls 74. Also, there was no correlation between bacterial alteration and symptom pattern, and even lactulose breath test was considered as an unreliable method to detect an association between bacterial overgrowth and IBS 74. In another study, breath hydrogen concentration was similar in IBS group and control group, and did not correlate with pain ratings in IBS patients, owing to the lack of objective diagnostic measures and inconsistent data 75.

It is unclear whether changes in small bowel bacterial flora could contribute to bloating in IBS patients, thus further studies are required to confirm these observations.

Food sensitivities

In addition to malabsorption syndromes such as celiac disease or lactase deficiency, various foods can also induce or exacerbate symptoms in patients with various functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs), particularly IBS. Strict elimination diets are usually not necessary, but restriction of identified foods, particularly at times of symptom flare-ups, is often helpful.

- Gluten. The clinical entity currently referred to as nonceliac gluten sensitivity is incompletely understood but seems to closely overlap with other functional gastrointestinal disorders 76

- Lactose. IBS may be exacerbated by milk or other dairy products, and lactose intolerance attributable to lactase deficiency may mimic the symptoms of IBS. In addition, at least 25% of patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders also have lactase deficiency. Lactose intolerance may be diagnosed using hydrogen breath testing, but this is not always accurate in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders; careful monitoring of symptoms in relation to ingestion of dairy products may be equally helpful 77.

- FODMAPs. Foods containing a variety of fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) may precipitate symptoms in certain individuals 78. Some patients find that avoiding certain FODMAP-containing foods may reduce IBS symptoms, but the routine use of highly restrictive exclusion diets has not been well studied and is not recommended 79.

Celiac disease

Celiac disease may present with bloating, flatulence, diarrhea or constipation, weight loss, anemia attributable to malabsorption of iron or folic acid or osteoporosis attributable to calcium malabsorption 10. If serologic testing is positive, duodenal biopsy should be performed. False-negative results may occur in serologic testing if the patient has already been on a gluten-free diet 10. Strict gluten-free diets are expensive and difficult to follow and should be advised only for patients with proven celiac disease 80.

Gastroparesis

Gastroparesis is a chronic disorder of delayed gastric emptying unrelated to mechanical obstruction. Most patients with gastroparesis experience nausea and vomiting in addition to dyspeptic symptoms. Idiopathic gastroparesis is most common in young or middle-aged women and sometimes develops after viral gastroenteritis; resolution of the disorder may take a year or more 81. Diabetic gastroparesis is a relatively rare complication (occurring in only 1% of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus) closely related to the degree of hyperglycemia 82; improved glycemic control often results in improved symptoms. 28 Bariatric surgery or fundoplication may occasionally cause postsurgical gastroparesis 81.

Impaired gastric accommodation

Reduced gastric accommodation, a disorder of the vagally mediated reflex that permits the stomach to adapt to food as it enters, has been recognized as distinct from delayed gastric emptying, but its exact role in dyspeptic symptoms is unclear. Testing is done only in specialized centers, and no specific treatments exist 83.

Gastric outlet obstruction

Gastric outlet obstruction may also cause bloating. Most gastric outlet obstruction is attributable to chronic peptic ulcer disease and scarring; in patients without alarm symptoms, the risk of malignancy is low. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori infection often results in long-term improvement of gastric outlet obstruction 38.

Intestinal Gas Accumulation

In the fasting state, the healthy gastrointestinal tract contains only about 100 mL of gas distributed almost equally among 6 compartments – stomach, small intestine, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon and distal (pelvic) colon. Postprandial volume of gas increases by about 65%, primarily in the pelvic colon 84. The excessive volume of intestinal gas has been proposed as the likely cause of bloating and distension, and many researchers have attempted to determine this view. A few studies using plain abdominal radiography demonstrated that intestinal gas volume was greater in patients with IBS than in controls (54% vs. 118%), however, the correlation between intra-abdominal gas contents and bloating was poor 85, 86. The vast majority of studies do not support that excessive gas induces bloating or abdominal pain. Lasser et al. (The role of intestinal gas in functional abdominal pain. Lasser RB, Bond JH, Levitt MD. N Engl J Med. 1975 Sep 11; 293(11):524-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1152877/()) conducted a study using argon washout technique, which demonstrated no differences in the accumulation of intestinal gas between patients with bloating and healthy subjects. More recent studies using CT scans combined with modern imaging analysis software have also shown that excess gas was not associated with abdominal bloating in most patients 87. Thus, these observations suggest that increased volume of gas may not be the main mechanism of bloating, but rather impaired gas transit or distribution are more often the sources of problem.

Altered Gut Motility and Impaired Gas Handling

Various abnormal motility patterns have been described in IBS patients, but none of those parameters can be used as diagnostic markers 88. Some authors have suggested that slow transit of food representing alteration in gut motility is related to bloating in IBS-Constipation patients 89. Also in a traditional experiment, normal volunteers being made constipated with loperamide, an agent known to slow transit, experienced bloating 90. Recently, IBS-Constipation patients with delayed orocecal and colonic transits have shown abdominal distension rather than bloating.15 Although delayed gastric emptying and slow intestinal transit in IBS-C patients were reported in many Asian studies, there are still controversies to define these motor disturbances as unique features in Asian IBS patients. Besides, the association between altered gut motility and IBS symptoms is pretty obscure. A recent study has also suggested that altered colon transit is of no or minor importance for IBS symptoms such as bloating or pain.

However, there are some different points with respect to the intestinal gas handling or transit. In a study by Serra et al. 91, they have shown that infused gas into the jejunum resulted in distension and abdominal bloating in most of the IBS patients (18 of 20), while only 20% (4 of 20) of control subjects developed symptoms like that. Another study using gas challenge technique has demonstrated that small intestinal gas transit (especially, jejunum) was more prolonged in patients with bloating than in controls, whereas colonic transit was normal. These data support that impaired small intestinal gas handling could be a mechanism of IBS or gas-bloating. Furthermore, a gas challenge test in healthy subjects during blocked rectal gas outflow showed that abdominal distension by girth measurement was similar in the jejunal and rectal infusion experiments, whereas abdominal symptoms including bloating were more significant in jejunal group. These data indicate that gas related symptom perception is determined by intraluminal gas distribution, whereas abdominal distension depends on the volume of intestinal gas. Besides, the patients with IBS or functional bloating are considered to evacuate intestinal gas less effectively, so that they are more likely to have symptoms of abdominal distension. This aspect of bloating’s mechanism has not been considered to be very relevant, but some researchers are interested in this view owing to the observations of anorectal function, especially in patients with constipation. Constipated patients with bloating plus distension exhibited a greater degree of anorectal dysfunction than those without distension. Moreover, self-restrained anal evacuation also increased symptom perception, while impaired gut propulsion caused by intravenous glucagon did not.

Taken together, ineffective anorectal evacuation as well as impaired gas handling may be possible mechanisms of abdominal distension and bloating. However, the data on the link between altered food transit of gut and bloating are not consistent, although they probably account for bloating in some of the IBS patients.

Abnormal abdominal-diaphragmatic reflexes

The abdominal cavity is determined by the placement of the walls of abdominal cavity including diaphragm, vertebral column and abdominal wall musculature. Even if there is no increase in intra-abdominal volume, a change of the position of abdominal cavity components may produce abdominal distension. Thus, there have been some efforts to evaluate the relationship between bloating and lumbar lordosis or weakened abdominal muscles. In one classic report, Sullivan suggested that the patients with bloating have weak abdominal muscles and frequently had recently gained weight than controls 92. But another study measuring upper and lower abdominal wall activities using surface electromyography has suggested that there were no differences in abdominal muscle activities between the patients and the controls. Moreover, in an early CT study, some IBS patients showed a tendency of lumbar lordosis but not consistent, and a change in lumbar lordosis did not correlate in any way with the changes in abdominal girth. Also, there were no noticeable changes in position of the diaphragm.

Tremolaterra et al. 93 reported that intestinal gas load was associated with a significant increment in abdominal wall muscle activity in healthy subjects. In contrast, the response to gas infusion was impaired in patients with bloating, and rather a paradoxical relaxation of the internal oblique muscles was noted. Further study using modern CT analysis with electromyography from Barcelona group has provided a novel concept of abnormal abdomino-phrenic reflexes for abdominal bloating and distension. Since then, several studies have demonstrated that abdomino-phrenic dyssynergia is one of main factors for abdominal distension and bloating. In healthy adults, colonic gas infusion increases anterior wall tone and relaxes the diaphragm at the same time. On the contrary, patients with bloating have shown diaphragmatic contraction (descent) and relaxation of the internal oblique muscle with the same gas load 94, 95.

Abdominophrenic dyssynergia

A paradoxical abdominophrenic response, called abdominophrenic dyssynergia, develops in some patients with chronic bloating and distension 13. During this process the diaphragm contracts (descends) and the anterior abdominal wall muscles relax 96. This response is in contrast to the normal physiologic response to increased intraluminal gas, whereby the diaphragm relaxes and the anterior abdominal muscles contract in order to increase the craniocaudal capacity of the abdominal cavity without abdominal protrusion (see Figure 4). An elegant CT scan study demonstrated that patients with functional bloating have significant abdominal wall protrusion and diaphragmatic descent with relatively small increases in intraluminal gas. In comparison, patients with bloating and intestinal dysmotility were found to have marked increases in intraluminal gas content with resulting diaphragmatic ascent 97. Abdominophrenic dyssynergia has also been identified in patients with functional dyspepsia and symptoms of postprandial bloating 98.

Figure 4. Normal and abnormal viscerosomatic reflexes

[Source 13 ]Altered microbiota

No studies have focused solely on the implications of the gut microbiome in the pathogenesis of symptoms of abdominal bloating or distension. In contrast, numerous studies have described the role of the gut microbiota in disorders of gastrointestinal motility, sensation, and intestinal permeability 99. Quantitative and qualitative differences in the intestinal microbiota have been identified comparing patients with IBS and healthy control subjects 100, 101. One study noted significant reductions in specific taxa from members of the Ruminococcaceae and Eubacteriaceae families among IBS patients without bloating compared with IBS patients with bloating and healthy control subjects 102.

Visceral hypersensitivity

The sensation of bloating may originate from abdominal viscera in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders, in whom normal stimuli or small variations of gas content within the gut may be perceived as bloating. IBS patients with symptoms of bloating alone have heightened visceral hypersensitivity compared with those with symptoms of bloating and distension 103. Indeed, it has been well recognized that the patients with IBS have lower visceral perception threshold than healthy controls 104, 105 and it has been speculated that this process might be associated with the sensation of bloating. Postprandial sensitivity to gastric balloon distension was found strongly correlated with postprandial symptoms, such as bloating, in functional dyspepsia patients 106. Conscious perception of intraluminal content and abdominal distension may contribute to symptomatic bloating and this can be amplified by complex brain-gut neural pathways, further influenced by factors such as anxiety, depression, somatization, and hypervigilance 107.

Kellow et al. 108 revealed that threshold for perception of small bowel contraction was lower than normal in some patients with IBS. Also, altered rectal perception assessed by phasic balloon distension has been reported in IBS patients. In addition, a gas challenge test proved a role of sensory disturbances in IBS patients, and recent clinical experiment has demonstrated that bloating without visible distension is associated with visceral hypersensitivity.

The autonomic nervous system may also contribute to modulation of the visceral sensitivity. Sympathetic activation is known to increase the perception of intestinal distension in functional dyspepsia patients; likewise, autonomic dysfunction could affect the visceral sensitivity in IBS patients. This mechanism may play a role in bloating. Moreover, it has been proposed that visceral perception may be influenced by cognitive mechanism. That is, IBS patients with bloating pay more attention to their abdominal symptoms, which is a kind of hyper-vigilance. Also, a report indicated that female patients with IBS had worsening of abdominal pain and bloating during their peri-menstrual phase, at which time heightened rectal sensitivity might have contributed to bloating, but not to distension. Taken together, altered sensory threshold combined with altered conscious perception may explain the mechanism of bloating.

Abnormal gastrointestinal motility

Bloating is common in patients with gastroparesis (over 50%) and those with small bowel dysmotility (eg, chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction and scleroderma) 109. A prospective study of more than 2000 patients with functional constipation and irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C) demonstrated that over 90% reported symptoms of bloating 110. In IBS-C patients, those with prolonged colonic transit were shown to have greater abdominal distension compared with patients with normal transit 111. Patients with functional bloating and IBS have impaired gas clearance from the proximal colon but normal colonic accommodation to gas infusion 112.

Food Intolerance and Carbohydrate Malabsorption

It is well recognized that dietary habits may be responsible for abdominal symptoms, and there have been efforts to prove the relationship between diet and IBS symptoms. Fiber overload has long been regarded as worsening factor of IBS symptoms through decreased small bowel motility or intraluminal bulking 113, 114. In addition, lactose intolerance may contribute to symptom development in IBS patients. In the small intestine, disaccharides are split by intestinal enzymes into monosaccharides which are then absorbed. If this process is not carried out, the disaccharide reaches the colon, in turn is split by bacterial enzymes into short chain carbonic acids and gases. Hence, malabsorption of lactose may produce the symptom of bloating in patients with IBS or functional bloating. Additionally, a new hypothesis is proposed, by which excessive delivery of highly fermentable but poorly absorbed short chain carbohydrates and polyols (collectively termed FODMAPs; fermentable oligo-, di- and mono-saccharides and polyols) to the small intestine and colon may contribute to the development of GI symptoms. FODMAPs are small molecules that are osmotically active and very rapidly fermentable compared with long-chain carbohydrates. These molecules induce relatively selective bacterial proliferation, especially of bifidobacterium, and it has been demonstrated indirectly that these can lead to expansion of bacterial populations in distal small intestine 115, 116, 117. Thus, high FODMAP diet has demonstrated prolonged hydrogen production in the intestine, colonic distension by fermentation, increased colonic fluid delivery by osmotic load within the bowel lumen, and GI symptom generation 118, 119.

Table 1. Foods High in Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols (FODMAPs) and Suitable Alternatives

| FODMAP | Foods high in FODMAPs | Suitable alternatives low in FODMAPs |

|---|---|---|

| Excess fructose | Fruits: apple, clingstone peach, mango, nashi pear, pear, sugar snap pea, tinned fruit in natural juice, watermelon | Fruits: banana, blueberry, cantaloupe, carambola, durian, grape, grapefruit, honeydew melon, kiwi, lemon, lime, orange, passion fruit, pawpaw, raspberry, strawberry, tangelo |

| Honey sweeteners: fructose, high-fructose corn syrup | Honey substitutes: golden syrup, maple syrup | |

| Large total fructose dose: concentrated fruit sources, large servings of fruit, dried fruit, fruit juice | Sweeteners: any sweeteners except polyols | |

| Lactose | Milk: regular and low-fat cow, goat, and sheep milk; ice cream | Milk: lactose-free milk, rice milk Ice cream substitutes: gelato, sorbet |

| Yogurts: regular and low-fat yogurts | Yogurts: lactose-free yogurts | |

| Cheeses: soft and fresh cheeses | Cheeses: hard cheeses | |

| Oligosaccharides (fructans and/or galactans) | Vegetables: artichoke, asparagus, beetroot, broccoli, Brussels sprout, cabbage, fennel, garlic, leek, okra, onion, pea, shallot | Vegetables: bamboo shoot, bok choy, capsicum, carrot, celery, chives, choko, choy sum, corn, eggplant, green bean, lettuce, parsnip, pumpkin, silverbeet, spring onion (green part only) |

| Cereals: rye and wheat cereals when eaten in large amounts (eg, biscuit, bread, couscous, cracker, pasta) | Onion/garlic substitutes: garlic-infused oil | |

| Legumes: baked bean, chickpea, lentil, red kidney bean | Cereals: gluten-free and spelt bread/cereal products | |

| Fruits: custard apple, persimmon, rambutan, watermelon, white peach | Fruit: tomato | |

| Polyols | Fruits: apple, apricot, avocado, cherry, longon, lychee, nashi pear, nectarine, peach, pear, plum, prune, watermelon | Fruits: banana, blueberry, cantaloupe, carambola, durian, grape, grapefruit, honeydew melon, kiwi, lemon, lime, orange, passion fruit, pawpaw, raspberry |

| Vegetables: cauliflower, mushroom, snow pea | ||

| Sweeteners: isomalt, maltitol, mannitol, sorbitol, xylitol, and other sweeteners ending in “-ol” | Sweeteners: glucose, sugar (sucrose), other artificial sweeteners not ending in “-ol” |

Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols (FODMAPs)

The acronym FODMAPs was created to describe poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates that can lead to excessive fluid and gas accumulation, resulting in bloating, abdominal pain, and distension (Figure 5). FODMAPs are found in a wide variety of foods, including those containing lactose, fructose in excess of glucose, fructans, galacto-oligosaccharides, and polyols (sorbitol, mannitol, xylitol, and maltitol). All FODMAPs have poor absorption and rapid fermentation, and they are comprised of small, osmotically active molecules. FODMAPs are poorly absorbed for a number of reasons, including the absence of luminal enzymes capable of hydrolyzing the glycosidic bonds contained in carbohydrates, the absence or low activity of brush border enzymes (eg, lactase), or the presence of low-capacity epithelial transporters (fructose, glucose transporter 2 [GLUT-2], and glucose transporter 5 [GLUT-5]). Fructose, which is an important FODMAP in the Western diet, is absorbed across villous epithelium through low-capacity, carrier-mediated diffusion involving GLUT-5. The absorption of free fructose is markedly enhanced in the presence of glucose via GLUT-2. Therefore, if fructose is present in excess of glucose, the risk of fructose malabsorption is increased. In addition, some molecules, such as polyols, are too large for simple diffusion. The fermentation rate is determined by the chain length of the carbohydrate 121.

For example, oligosaccharides are rapidly fermented, compared to polysaccharides. Fermentation results in the production of carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and/or methane gas. Finally, small, osmotically active molecules draw more water and other liquid into the small bowel. Given these properties, a diet low in FODMAPs has become a potential therapy for IBS patients.

Figure 5. Ingested fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) are poorly absorbed in the small intestine. Their small molecular size results in an osmotic effect, drawing water (H20) through to the large intestine. FODMAPs are then fermented by colonic microflora, producing hydrogen (H2) and/or methane gas (CH4). The increase in fluid and gas leads to diarrhea, bloating, flatulence, abdominal pain, and distension.

[Source 120]Intraluminal Contents

Levitt et al. 122 suggested that abdominal bloating might develop without gas retention, but by other gut contents. They had undertaken randomized, double-blind, crossover study of gaseous symptoms by observing the responses of healthy subjects to dietary supplement with lactulose or 2 types of fibers (psyllium or methylcellulose). In lactulose group, gas passages, subjective perception of rectal gas and breath hydrogen excretion were significantly increased, but not in fiber groups. However, the sensation of bloating was increased in all 3 groups. Thus, it has been proposed that increased intra-abdominal bulk, not gaseous filling, might be a cause of abdominal bloating. In another study, bran accelerated small bowel transit and ascending colon clearance without causing symptom in controls, but small bowel transit has not further been accelerated in IBS patients with bloating. Thus, they speculated that bran might cause increased bulking effect in the colon, which led to the exacerbation of bloating in IBS patients 123. Francis and Whorwell 113 even proposed that use of the bran in IBS should be reconsidered, because excessive consumption of bran might give rise to symptoms such as bloating in IBS patients. Although more studies are needed for further understanding of their relationship, it could be possible that intraluminal bulking aggravates the bloating in some IBS patients.

Hard stool/Constipation

Many constipated patients complain of bloating.14 Also there is a tendency of its being more common in IBS-Constipation patients than IBS-Diarrhea patients, though it is not statistically significant in some studies 124, 125. Distension of the rectum by retained feces slows small intestinal transit as well as colonic transit, probably explaining the aggravated bloating in constipated patients 126, 127. Thus it seems reasonable that constipation or hard/lumpy stool induces alteration of gut motility and thus maybe increases bacterial fermentation. In addition, constipation may accelerate bloating by intraluminal bulking effect in the same manner as bran.

Psychological Aspects

Bloating is a frequent complaint of women with IBS. Park et al. 128 proposed that there was a tendency to increase the index of psychological distress when the bloating was more severe. Also, patients with bloating revealed increased anxiety and depression, which allows the hypothesis that psychological distress may contribute to the perceived severity of bloating 129. Additionally, in large population surveys, bloating was significantly related with psychiatric dysfunction such as major depressive disorder, panic disorder and sleeping difficulties 130, 131. Nevertheless, other studies have failed to demonstrate the relationships between psychological distress and either bloating or distension 132. However, it is unclear whether or not there is an actual relationship between bloating and psychosocial distress, and further studies are needed to demonstrate it.

Gender and Sex Hormones

In a population based study in USA, female gender was significantly associated with increased symptoms of bloating and distension in IBS, and similar findings have been reported so far. Although the question of the gender role in IBS has been raised from many studies, the mechanisms of gender differences in bloating and distension are unclear. Some studies have suggested that bloating is one of the frequent symptoms of menstruation as aforementioned 133, 134. Hormonal effect has also been speculated, that is, the variation of reproductive hormones throughout the menstrual cycle and after the menopause may influence the gut motility and visceral perception. Additionally, difference in symptom expression by gender is presented as a potential explanation. Although more investigations regarding the underlying mechanisms for these disparities remain to be determined, it seems to be possible to speculate that the hormonal fluctuation may contribute to bloating in female IBS patients.

Pelvic floor dysfunction

Patients with anorectal motor dysfunction may experience bloating and distension owing to an impaired ability to effectively evacuate both flatus and stool. Prolonged balloon expulsion correlates with symptoms of distension among patients with constipation 135. Pelvic outlet obstruction has been shown to delay colonic transit 136.

Bloating diagnosis

Determining the underlying cause of abdominal bloating and distension can be challenging. Your doctor will likely determine what’s causing your abdominal bloating based on:

- Your medical history

- Onset and timing of symptoms

- Use of medications and supplements

- Relationship to diet

- Surgical history

- Bowel movement habits and patterns

- A review of your dietary habits

- A physical exam

Conducting a thorough clinical history and physical examination that includes the following details will help determine which type of testing may be needed:

During the physical exam, your doctor may touch your abdomen to determine if there is any tenderness and if anything feels abnormal. A physical examination should include a rectal examination to identify an evacuation disorder in patients with constipation 19. Listening to the sound of your abdomen with a stethoscope can help your doctor determine how well your digestive tract is working.

Depending on your exam and presence of other signs and symptoms — such as weight loss, blood in your stool or diarrhea — your doctor may order additional diagnostic tests.

Testing should be based on suspected cause and can include:

- Breath tests are a safe, widely available, inexpensive and noninvasive way to determine whether SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth) or food intolerance is responsible. Breath tests measure carbohydrate maldigestion based on the carbohydrate of interest. Test substances include glucose, lactulose, fructose, sorbitol, sucrose, and inulin 137. Gas produced during colonic fermentation from nonabsorbed carbohydrates diffuses into the systemic circulation and is excreted in the breath, where it can be quantified 138. Hydrogen and methane are the gases that are exclusively produced in the gastrointestinal tract from microbial fermentation.

- Lactose breath test: The absorption of lactose, a disaccharide composed of glucose and galactose, is dependent on the activity of the brush border enzyme lactase-phlorizin hydrolase 139. Lactose maldigestion produces symptoms of bloating, abdominal cramping, flatulence, and diarrhea. Twenty-five grams of lactose is a standard test dose. An increase of ≥20 ppm of hydrogen or >10 ppm of methane above baseline with associated GI symptoms is a positive test. Lactose breath test has good sensitivity (mean value of 77.5%) and excellent specificity (mean value of 97.6%) 138.

- Fructose breath test: Fructose is a naturally occurring sugar in fruits, different foods, and sweeteners. The absorptive capacity for fructose in the small intestine is minimal; unabsorbed fructose leads to symptoms of bloating and diarrhea. Controversies exist regarding the amount of fructose to use during breath test 140, although the most widely accepted dose is 25 g. A positive test is an increase ≥20 ppm of hydrogen or >10 ppm of methane above baseline with associated gastrointestinal symptoms.

- Upper endoscopy for patients with alarm symptoms (recurrent nausea and vomiting, unexplained anemia, hematemesis, weight loss >10% of body weight or a family history of gastroesophageal malignancy) or when gastric outlet obstruction, gastroparesis or functional dyspepsia is suspected. Upper endoscopy also provides an opportunity to biopsy the small intestine and stomach to exclude organic disorders as causes of bloating.

- Celiac serologies to help determine if malabsorption of wheat and gluten is occurring. Malabsorption of wheat and gluten may cause symptoms of bloating, distension and accelerated gastrointestinal transit in untreated celiac disease 141. Serologic testing using tissue transglutaminase and IgA is recommended for patients with a high pretest probability for celiac disease 142. Upper endoscopy with small bowel biopsies should be performed to confirm celiac disease in those who test positive.

- Abdominal imaging, including computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging enterography for patients with constipation, prior abdominal surgery, Crohn’s disease, or known or suspected small bowel dysmotility

- Complete gastrointestinal transit assessment, using scintigraphy or a wireless motility capsule, to confirm dysmotility or constipation secondary to slow transit. Bloating is prevalent in patients with gastroparesis 143. A 4-hour scintigraphic gastric emptying study is the standard test to diagnose gastroparesis or rapid gastric emptying 144. Complete gastrointestinal transit assessment with either scintigraphy 145 or a wireless motility capsule 146 may be useful in patients with dysmotility or constipation thought secondary to slow transit. A gastric barostat or single-photon-emission CT (SPECT) imaging of the stomach can identify impaired gastric accommodation, although these tests are not widely available 147.

- Anorectal manometry with balloon expulsion for evaluation of anorectal disorders. Patients with severe constipation and bloating and with characteristic rectal examination findings suggesting a pelvic floor disorder should be evaluated objectively 148. Anorectal manometry with balloon expulsion is the most widely used test for evaluation of anorectal disorders 149.

- Defecography, either barium or magnetic resonance imaging, provides an additional anatomical and functional assessment of the pelvic floor 150

Bloating treatment

If your bloating are caused by another health problem, treating the underlying condition may offer relief. Otherwise, bothersome gas is generally treated with dietary measures, lifestyle modifications or over-the-counter medications. Although the solution isn’t the same for everyone, with a little trial and error, most people are able to find some relief.

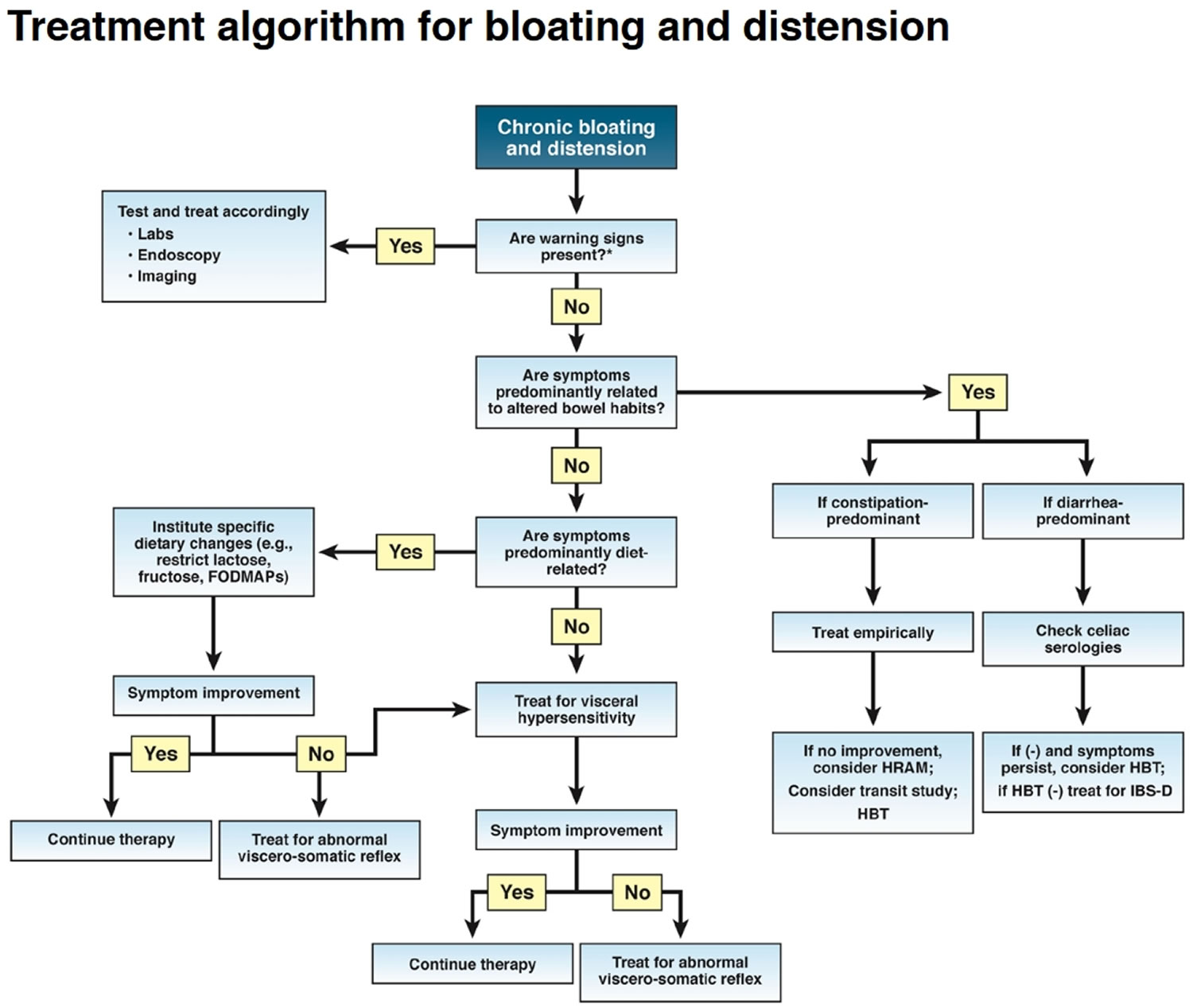

The following sections highlight therapeutic approaches for the treatment of chronic bloating and distension (Figure 6). Treatments are listed in a sequence commonly followed in clinical practice, recognizing that treatment needs to be individualized.

Figure 6. Bloating treatment algorithm

[Source 13 ]Dietary changes

Dietary changes may help reduce the amount of gas your body produces or help gas move more quickly through your system. Keeping a diary of your diet and gas symptoms will help your doctor and you determine the best options for changes in your diet. You may need to eliminate some items or eat smaller portions of others.

General dietary guidance:

- Eat in moderation;

- Get adequate but not excessive fiber;

- Decrease consumption of fatty and spicy foods;

- Avoid caffeine, soft drinks, carbonation, and artificial sweeteners. Artificial sweeteners that contain poorly absorbed sugar alcohols such as sorbitol, mannitol, xylitol, and glycerol promote gas production 151. Restricting nonabsorbable sugars led to symptomatic improvement in 81% patients with functional abdominal bloating who had documented sugar malabsorption 152.

- Restricted diet: Diets restricted in fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs) may improve IBS symptoms in some patients, but questions remain regarding their long-term safety, effectiveness, and practicality.

- Gluten-free diet: The long-term effects of gluten-free diets on the microbiome and general nutrition are uncertain; they may lead to increased fat and sugar consumption. Strict gluten-free diets are expensive and difficult to follow and should be advised only for patients with proven celiac disease.

Approximately 70% of patients considered to have nonceliac gluten sensitivity report bloating 153. IBS patients, previously symptomatically controlled on a gluten-free diet, when challenged with gluten for 1 week had significantly worse bloating compared with placebo 154. However, the role of gluten as a dietary source of bloating and other gastrointestinal symptoms is controversial. Evidence suggests that fructans and FODMAPs (fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides) are the true culprits 153. Two studies have shown that IBS patients treated with a low-FODMAP diet noted improvement in bloating and distension 155, 156.

Reducing or eliminating the following dietary factors may improve gas symptoms:

- High-fiber foods. High-fiber foods that can cause gas include beans, onions, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower, artichokes, asparagus, pears, apples, peaches, prunes, whole wheat and bran. You can experiment with which foods affect you most. You may avoid high-fiber foods for a couple of weeks and gradually add them back. Talk to your doctor to ensure you maintain a healthy intake of dietary fiber.

- Dairy. Reducing dairy products from your diet can lessen symptoms. You also may try dairy products that are lactose-free or take milk products supplemented with lactase to help with digestion.

- Sugar substitutes. Eliminate or reduce sugar substitutes, or try a different substitute.

- Fried or fatty foods. Dietary fat delays the clearance of gas from the intestines. Cutting back on fried or fatty foods may reduce symptoms.

- Carbonated beverages. Avoid or reduce your intake of carbonated beverages.

- Fiber supplements. If you use a fiber supplement, talk to your doctor about the amount and type of supplement that is best for you.

- Water. To help prevent constipation, drink water with your meals, throughout the day and with fiber supplements.

Over-the-counter remedies

The following products may reduce gas symptoms for some people:

- Alpha-galactosidase (Beano, BeanAssist, others) helps break down carbohydrates in beans and other vegetables. You take the supplement just before eating a meal.

- Lactase supplements (Lactaid, Digest Dairy Plus, others) help you digest the sugar in dairy products (lactose). These reduce gas symptoms if you’re lactose intolerant. Talk to your doctor before using lactase supplements if you’re pregnant or breast-feeding.

- Simethicone (Gas-X, Mylanta Gas Minis, others) helps break up the bubbles in gas and may help gas pass through your digestive tract. There is little clinical evidence of its effectiveness in relieving gas symptoms.

- Activated charcoal (Actidose-Aqua, CharcoCaps, others) taken before and after a meal may reduce symptoms, but research has not shown a clear benefit. Also, it may interfere with your body’s ability to absorb medications. Charcoal may stain the inside of your mouth and your clothing.

Exercise

Regular daily exercise decreases symptoms of IBS and chronic idiopathic constipation.

Fiber

Soluble fiber (psyllium; 25 to 30 g daily) provides a small benefit for some patients with IBS, but it can also worsen bloating. Insoluble fiber (bran, methylcellulose, calcium polycarbophil; two heaped teaspoons daily) is somewhat more effective for chronic idiopathic constipation than soluble fiber, but it can worsen bloating and flatulence in many patients. Increase fiber gradually to minimize bloating, distention, flatulence, and cramping. Worsening of gas and bloating suggests underlying dyssynergic defecation (pelvic floor dysfunction).

How to get rid of bloating

Dietary Interventions

Food intake may play a key role in perpetuating symptoms in IBS patients, so a careful history taking for diet should be taken. Many retrospective observational studies have shown that the reduced intake of large amounts of highly fermentable, poorly absorbed short chain carbohydrates (FODMAPs) may reduce bloating in IBS patients. Finally, the low FODMAP diet was developed at Monash University in Melbourne and recently, the first prospective study confirming the efficacy of low FODMAP diet for IBS patients was reported. Besides, patients with IBS who had also fructose malabsorption were significantly more likely to respond to the low FODMAP diet than those without fructose malabsorption.

Probiotics