What are Carbohydrates

Carbohydrate is a biological molecule consisting of carbon (C), hydrogen (H) and oxygen (O) atoms, that is synonymous with ‘saccharide’ (sugar), a group that includes sugars, starch, and cellulose. The word saccharide comes from the Greek word sákkharon, meaning “sugar”. Carbohydrates are the most abundant biomolecules in nature. Carbohydrates can be found in humans, animals, plants and in micro-organisms.

Carbohydrates perform numerous roles in living organisms. Polysaccharides serve for the storage of energy (e.g. starch and glycogen) and as structural components (e.g. cellulose in plants and part of cartilage, tendons). The 5-carbon monosaccharide ribose is an important component of coenzymes (e.g. ATP, FAD and NAD) and the backbone of the genetic molecule known as RNA. The related deoxyribose is a component of DNA. Saccharides and their derivatives include many other important biomolecules that play key roles in the immune system, fertilization, preventing pathogenesis, blood clotting, and development 1.

Carbohydrates are called simple or complex, depending on their chemical structure. Simple carbohydrates include sugars found naturally in foods such as fruits, vegetables, milk, and milk products. They also include sugars added during food processing and refining. Complex carbohydrates include whole grain breads and cereals, starchy vegetables and legumes. Many of the complex carbohydrates are good sources of fiber.

Table 1. The Different Types of Sugar

The saccharides (sugar) are divided into four chemical groups:

- Monosaccharides (simple sugars). Monosaccharides are simplest sugars and they cannot be hydrolysed further into smaller carbohydrates e.g. glucose, fructose, mannose and galactose. Glucose is the essential energy source for all body functions. Galactose seldom occurs freely in nature. Galactose binds with glucose to form sugar in milk – lactose. Fructose “the fruit sugar” is the sweetest of all sugars (1.5X sweeter than sucrose), occurs naturally in fruits, maple syrup and honey.

- Disaccharides (simple sugars) – are condensation products of 2 monosaccharide units. Disaccharides examples: Sucrose (table sugar, cane sugar, beet sugar) = glucose + fructose; Lactose = glucose + galactose; Maltose = glucose + glucose; Trehalose = glucose + glucose. Maltose is produced when starch breaks down. Maltose is used naturally in fermentation reactions of alcohol and beer manufacturing.

- Oligosaccharides (complex sugars) – are condensation products of 2-10 monosaccharide units. Most important Oligosaccharides are Disaccharides.

- Polysaccharides (complex sugars) – are condensation products of more than 10 monosaccharide units, which can either be linear or branched polymers. For examples, starch, glycogen, cellulose, dextran, inulin, chitin, proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans. Cellulose gives structure to plants and fiber to our diet. Glycogen is the storage form of glucose in the body that is produced by your liver. Your liver synthesize glycogen after a meal to maintain blood glucose levels. Glycogen is stored in your liver and muscles. Glycogen is not a significant food source of carbohydrate. Glycogen is found in tiny amounts in meat sources and none in plants. Fiber is the name given to a range of compounds found in the cell walls of vegetables, fruits, pulses and cereal grains. Fibre that cannot be digested helps other food and waste products move through the gut more easily.

Monosaccharides and disaccharides, the smallest carbohydrates, are commonly referred to as sugars.

While the scientific nomenclature of carbohydrates is complex, the names of the monosaccharides and disaccharides very often end in the suffix -ose. For example, grape sugar is the monosaccharide – “glucose”, fruit sugar (e.g. honey, maple syrup) is the monosaccharide – “frutose”, cane sugar (& beet sugar) is the disaccharide – “sucrose”, and milk sugar is the disaccharide “lactose”. Many people have problems digesting large amounts of lactose – lactose intolerance.

Figure 1. Glucose

Figure 2. Sucrose (Sugar) made up of one Glucose and one Fructose molecule

Figure 3. Glycogen is a polymer of glucose (up to 120,000 glucose molecules)

Figure 4. Cellulose is composed of a long chain of at least 500 glucose molecules (the wood in your furniture, the pages in your notebook and the cotton in your clothing are made of cellulose)

Carbohydrates are found in a wide array of both healthy and unhealthy foods—bread, beans, milk, popcorn, potatoes, cookies, spaghetti, soft drinks, corn, and cherry pie. They also come in a variety of forms. The most common and abundant forms are sugars, fibers, and starches.

Foods high in carbohydrates are an important part of a healthy diet – in fact over 65% of the foods in our diet consist of carbohydrates. Carbohydrates provide the body with glucose, which is converted to energy used to support bodily functions and physical activity. But carbohydrate quality is important; some types of carbohydrate-rich foods are better than others:

The healthiest sources of carbohydrates—unprocessed or minimally processed whole grains, vegetables, fruits and beans—promote good health by delivering vitamins, minerals, fiber, and a host of important phytonutrients.

Unhealthier sources of carbohydrates include white bread, pastries, sodas, and other highly processed or refined foods. These items contain easily digested carbohydrates that may contribute to weight gain, interfere with weight loss, and promote diabetes and heart disease.

The Healthy Eating Plate recommends filling most of your plate with healthy carbohydrates – with vegetables (except potatoes) and fruits taking up about half of your plate, and whole grains filling up about one fourth of your plate.

Summary of Function of Carbohydrates in Cells

- Major source of energy for the cell, for daily activity and energy of life. 1 gram of carbohydrate = 4 calorie

- Major structural component of plant cell. Fiber is the name given to a range of compounds found in the cell walls of vegetables, fruits, pulses and cereal grains. Fiber that cannot be digested helps other food and waste products move through the gut more easily.

- Immediate energy in the form of Glucose

- Reserve or stored energy in the form of Glycogen

- Excess carbohydrate is converted into Fat

What are Refined Carbohydrates or Refined Carbs ?

The healthiest sources of carbohydrates—unprocessed or minimally processed whole grains, vegetables, fruits and beans—promote good health by delivering vitamins, minerals, fiber, and a host of important phytonutrients. The process of refining a food not only removes the fiber, but it also removes much of the food’s nutritional value, including B-complex vitamins, healthy oils and fat-soluble vitamins. Refined carbohydrates are plant-based foods that have the whole grain extracted during processing, where the fibers, starches, vitamins and minerals have been removed, leaving behind refined carbohydrates. Refined carbohydrates sources include bottled fruit juices, juice concentrates, white bread, pastries, sodas, donuts, cakes, cookies, sweets, chips and other highly processed or refined foods. These items contain easily digested carbohydrates that may contribute to weight gain, interfere with weight loss, and promote diabetes and heart disease 2.

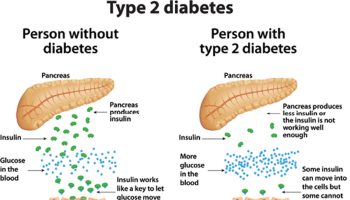

Typically, foods with highly processed refined carbohydrates (eg, white bread) are digested at a much faster rate and have higher glycemic index (high GI) values than do more compact granules (low-starch gelatinization) and high amounts of viscose soluble fiber (eg, barley, oats, and rye) foods. These refined carbohydrates are more rapidly attacked by digestive enzymes due to grinding or milling that reduces particle size and removes most of the bran and the germ. Numerous epidemiologic studies have found that higher intake of refined carbohydrates (reflected by increased dietary Glycemic Load) is associated with greater risk of type 2 diabetes and heart disease, whereas higher consumption of whole grains protects against these conditions 3.

Studies have shown eating more — vegetables, nuts, fruits, and whole grains — were associated with less weight gain when consumption was actually increased 4. Obviously, such foods provide calories and cannot violate thermodynamic laws. Their inverse associations with weight gain suggest that the increase in their consumption reduced the intake of other foods to a greater (caloric) extent, decreasing the overall amount of energy consumed. Higher fiber content and slower digestion of these foods would augment satiety, and their increased consumption would also displace other, more highly processed foods in the diet, providing plausible biologic mechanisms whereby persons who eat more fruits, nuts, vegetables, and whole grains would gain less weight over time.

On the other hand, studies also show strong positive associations with weight gain were seen for starches, refined grains, and processed foods. Weight gain associated with increased consumption of refined grains (0.39 lb per serving per day) was similar to that for sweets and desserts (0.41 lb per serving per day). Foods that contained higher amounts of refined carbohydrates — whether these were added (e.g., in sweets and desserts) or were not added (e.g., in refined grains) — were associated with weight gain in similar ways, and potato products (which are low in sugars and high in starches) showed the strongest associations with weight gain 4. These findings are consistent with those suggested by the results in limited short-term trials: consumption of starches and refined grains may be less satiating, increasing subsequent hunger signals and total caloric intake, as compared with equivalent numbers of calories obtained from less processed, higher-fiber foods that also contain healthy fats and protein 5. Consumption of processed foods that are higher in starches, refined grains, fats, and sugars can increase weight gain 6, 7, 8. The consumption of high-carbohydrate beverages except milk were positively associated with weight gain, these findings were consistent with those for refined carbohydrates and starches consumed in foods 4.

Refined carbohydrates are composed of sugars (such as fructose and glucose) which have simple chemical structures composed of only one sugar (monosaccharides) or two sugars (disaccharides). Simple carbohydrates are easily and quickly utilized for energy by the body because of their simple chemical structure, often leading to a faster rise in blood sugar and insulin secretion from the pancreas – which can have negative health effects.

When it comes to carbohydrates, what’s most important is the type of carbohydrate you choose to eat because some sources are healthier than others. The amount of carbohydrate in the diet – high or low – is less important than the type of carbohydrate in the diet. For example, healthy, whole grains such as whole wheat bread, rye, barley and quinoa are better choices than highly refined white bread or French fries. For example, whole grain whole wheat flour.

The obesity epidemic and growing intake of refined carbohydrates have created a “perfect storm” for the development of cardio-metabolic disorders. For this reason, reduction of refined carbohydrate intake should be a top public health priority. Several dietary strategies can be used to achieve this goal. These include replacing carbohydrates (especially refined grains and sugar) with unsaturated fats and/or healthy sources of protein and exchanging whole grains for refined ones. A combination of these approaches can increase flexibility in macronutrient composition and thus long-term adherence. In addition, limiting sugar-sweetened beverage consumption, a major source of dietary GL and excess calories, has been associated with lower risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, and coronary heart disease 9.

Many people are confused about carbohydrates, but keep in mind that it’s more important to eat carbohydrates from healthy foods than to follow a strict diet limiting or counting the number of grams of carbohydrates consumed.

To further explain how different kinds of carbohydrate-rich foods directly affect blood sugar and chronic diseases, the glycemic index (GI) was developed and is considered a better way of categorizing carbohydrates, especially starchy foods.

Table 2. List of refined carbs for more than 100 common foods with their glycemic index and glycemic load, per serving.

| FOOD | Glycemic index (glucose = 100) | Serving size (grams) | Glycemic load per serving |

| BAKERY PRODUCTS AND BREADS | |||

| Banana cake, made with sugar | 47 | 60 | 14 |

| Banana cake, made without sugar | 55 | 60 | 12 |

| Sponge cake, plain | 46 | 63 | 17 |

| Vanilla cake made from packet mix with vanilla frosting (Betty Crocker) | 42 | 111 | 24 |

| Apple muffin, made with rolled oats and sugar | 44 | 60 | 13 |

| Apple muffin, made with rolled oats and without sugar | 48 | 60 | 9 |

| Waffles, Aunt Jemima® | 76 | 35 | 10 |

| Bagel, white, frozen | 72 | 70 | 25 |

| Baguette, white, plain | 95 | 30 | 14 |

| Coarse barley bread, 80% kernels | 34 | 30 | 7 |

| Hamburger bun | 61 | 30 | 9 |

| Kaiser roll | 73 | 30 | 12 |

| Pumpernickel bread | 56 | 30 | 7 |

| 50% cracked wheat kernel bread | 58 | 30 | 12 |

| White wheat flour bread, average | 75 | 30 | 11 |

| Wonder® bread, average | 73 | 30 | 10 |

| Whole wheat bread, average | 69 | 30 | 9 |

| 100% Whole Grain® bread (Natural Ovens) | 51 | 30 | 7 |

| Pita bread, white | 68 | 30 | 10 |

| Corn tortilla | 52 | 50 | 12 |

| Wheat tortilla | 30 | 50 | 8 |

| BEVERAGES | |||

| Coca Cola® (US formula) | 63 | 250 mL | 16 |

| Fanta®, orange soft drink | 68 | 250 mL | 23 |

| Lucozade®, original (sparkling glucose drink) | 95 | 250 mL | 40 |

| Apple juice, unsweetened | 41 | 250 mL | 12 |

| Cranberry juice cocktail (Ocean Spray®) | 68 | 250 mL | 24 |

| Gatorade, orange flavor (US formula) | 89 | 250 mL | 13 |

| Orange juice, unsweetened, average | 50 | 250 mL | 12 |

| Tomato juice, canned, no sugar added | 38 | 250 mL | 4 |

| BREAKFAST CEREALS AND RELATED PRODUCTS | |||

| All-Bran®, average | 44 | 30 | 9 |

| Coco Pops®, average | 77 | 30 | 20 |

| Cornflakes®, average | 81 | 30 | 20 |

| Cream of Wheat® | 66 | 250 | 17 |

| Cream of Wheat®, Instant | 74 | 250 | 22 |

| Grape-Nuts® | 75 | 30 | 16 |

| Muesli, average | 56 | 30 | 10 |

| Oatmeal, average | 55 | 250 | 13 |

| Instant oatmeal, average | 79 | 250 | 21 |

| Puffed wheat cereal | 80 | 30 | 17 |

| Raisin Bran® | 61 | 30 | 12 |

| Special K® (US formula) | 69 | 30 | 14 |

| GRAINS | |||

| Pearled barley, average | 25 | 150 | 11 |

| Sweet corn on the cob | 48 | 60 | 14 |

| Couscous | 65 | 150 | 9 |

| Quinoa | 53 | 150 | 13 |

| White rice, boiled, type non-specified | 72 | 150 | 29 |

| Quick cooking white basmati | 63 | 150 | 26 |

| Brown rice, steamed | 50 | 150 | 16 |

| Parboiled Converted white rice (Uncle Ben’s®) | 38 | 150 | 14 |

| Whole wheat kernels, average | 45 | 50 | 15 |

| Bulgur, average | 47 | 150 | 12 |

| COOKIES AND CRACKERS | |||

| Graham crackers | 74 | 25 | 13 |

| Vanilla wafers | 77 | 25 | 14 |

| Shortbread | 64 | 25 | 10 |

| Rice cakes, average | 82 | 25 | 17 |

| Rye crisps, average | 64 | 25 | 11 |

| Soda crackers | 74 | 25 | 12 |

| DAIRY PRODUCTS AND ALTERNATIVES | |||

| Ice cream, regular, average | 62 | 50 | 8 |

| Ice cream, premium (Sara Lee®) | 38 | 50 | 3 |

| Milk, full-fat, average | 31 | 250 mL | 4 |

| Milk, skim, average | 31 | 250 mL | 4 |

| Reduced-fat yogurt with fruit, average | 33 | 200 | 11 |

| FRUITS | |||

| Apple, average | 36 | 120 | 5 |

| Banana, raw, average | 48 | 120 | 11 |

| Dates, dried, average | 42 | 60 | 18 |

| Grapefruit | 25 | 120 | 3 |

| Grapes, black | 59 | 120 | 11 |

| Oranges, raw, average | 45 | 120 | 5 |

| Peach, average | 42 | 120 | 5 |

| Peach, canned in light syrup | 52 | 120 | 9 |

| Pear, raw, average | 38 | 120 | 4 |

| Pear, canned in pear juice | 44 | 120 | 5 |

| Prunes, pitted | 29 | 60 | 10 |

| Raisins | 64 | 60 | 28 |

| Watermelon | 72 | 120 | 4 |

| BEANS AND NUTS | |||

| Baked beans | 40 | 150 | 6 |

| Black-eyed peas | 50 | 150 | 15 |

| Black beans | 30 | 150 | 7 |

| Chickpeas | 10 | 150 | 3 |

| Chickpeas, canned in brine | 42 | 150 | 9 |

| Navy beans, average | 39 | 150 | 12 |

| Kidney beans, average | 34 | 150 | 9 |

| Lentils | 28 | 150 | 5 |

| Soy beans, average | 15 | 150 | 1 |

| Cashews, salted | 22 | 50 | 3 |

| Peanuts | 13 | 50 | 1 |

| PASTA and NOODLES | |||

| Fettucini | 32 | 180 | 15 |

| Macaroni, average | 50 | 180 | 24 |

| Macaroni and Cheese (Kraft®) | 64 | 180 | 33 |

| Spaghetti, white, boiled, average | 46 | 180 | 22 |

| Spaghetti, white, boiled 20 min | 58 | 180 | 26 |

| Spaghetti, whole-grain, boiled | 42 | 180 | 17 |

| SNACK FOODS | |||

| Corn chips, plain, salted | 42 | 50 | 11 |

| Fruit Roll-Ups® | 99 | 30 | 24 |

| M & M’s®, peanut | 33 | 30 | 6 |

| Microwave popcorn, plain, average | 65 | 20 | 7 |

| Potato chips, average | 56 | 50 | 12 |

| Pretzels, oven-baked | 83 | 30 | 16 |

| Snickers Bar®, average | 51 | 60 | 18 |

| VEGETABLES | |||

| Green peas | 54 | 80 | 4 |

| Carrots, average | 39 | 80 | 2 |

| Parsnips | 52 | 80 | 4 |

| Baked russet potato | 111 | 150 | 33 |

| Boiled white potato, average | 82 | 150 | 21 |

| Instant mashed potato, average | 87 | 150 | 17 |

| Sweet potato, average | 70 | 150 | 22 |

| Yam, average | 54 | 150 | 20 |

| MISCELLANEOUS | |||

| Hummus (chickpea salad dip) | 6 | 30 | 0 |

| Chicken nuggets, frozen, reheated in microwave oven 5 min | 46 | 100 | 7 |

| Pizza, plain baked dough, served with parmesan cheese and tomato sauce | 80 | 100 | 22 |

| Pizza, Super Supreme (Pizza Hut®) | 36 | 100 | 9 |

| Honey, average | 61 | 25 | 12 |

The complete list of the glycemic index and glycemic load for more than 1,000 foods can be found in the article “International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2008” by Fiona S. Atkinson, Kaye Foster-Powell, and Jennie C. Brand-Miller in the December 2008 issue of Diabetes Care, Vol. 31, number 12, pages 2281-2283 10.

Examples of refined carbs

Refined Breads

Many of the breads found on grocery store shelves are considered refined carbohydrates. These breads are often made from enriched and bleached flours, and these flours are typically listed as the first or second ingredient on the nutrition label. In addition, the list of ingredients will often include vitamins and minerals that are added during the post-refining, enrichment process. Sourdough, white and plain wheat bread are excellent examples of refined breads, whereas 100 percent whole-wheat or whole-grain breads are not refined.

Refined Rice

Like bread, some forms of rice are considered to be refined grains. White rice and most of the quick-cook rices are refined and, as a result, do not contain an intact grain. They may be enriched to enhance their nutritional profile, but they typically lack the fiber found in the non-refined brown rice. One cup of white rice counts as 2 ounces of refined grains.

Refined Cereals

Many of the sugary, cold cereals found in grocery stores are considered to be refined grains. They are typically made from enriched flour due to the refining of their original wheat, corn or oat grain. Refined cereals typically have 2 or fewer grams of fiber per serving, and one cup of a refined cereal, such as corn flakes, counts as 1 ounce of refined grains.

Refined Pasta

Unlike whole wheat or whole grain pasta, refined pasta lacks much of the fiber and the B-complex vitamins found in the unprocessed version. Like other processed starches, refined pasta may be enriched with nutrients such as folate, thiamin and riboflavin, and some versions of refined pasta may even have omega 3 fatty acids added during processing. Thus, if you prefer the less grainy taste of refined pasta, make sure that it has been fully enriched with the aforementioned nutrients.

Refined Snack Foods

Snack foods are typically made with refined carbs such as bleached flours and sugar in order to increase palatability. These snack foods have little nutritional value and, as a result, provide empty calories in the diet. Cakes, cookies, pie, candy and chips are all examples of refined snack foods, and according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, these foods should not constitute more than 120 to 330 calories per day.

List of refined carbs

Any foods that have been processed for quick consumption.

- Foods made with refined or “white” flour also contain less fiber and protein than whole-grain products.

- Snacks, such as crisps, sausage rolls, pies and pasties

- Granola bars

- Ice cream

- Donuts

- Cakes

- Twinkies

- Pastries

- Canned fruits with added sugar or syrup

- Sweets

- Fruit drinks

- Colas and carbonated sweetened beverages

- Energy drinks

- Sports drink

- Jams

- Crackers

- Dressings

- Sauces

- Cookies

- Fruit chews

- Pizzas

- Apple pies

- Anything with added sugar.

Sugar by Any Other Name

You don’t always see the word “sugar” on a food label. It sometimes goes by another name, like these:

- White sugar

- Brown sugar

- Raw sugar

- Agave nectar

- Brown rice syrup

- Corn syrup

- Corn syrup solids

- Coconut sugar

- Coconut palm sugar

- High-fructose corn syrup

- Invert sugar

- Dextrose

- Anhydrous dextrose

- Crystal dextrose

- Dextrin

- Evaporated cane juice

- Fructose sweetener

- Liquid fructose

- Glucose

- Lactose

- Honey

- Malt syrup

- Maple syrup

- Molasses

- Pancake syrup

- Sucrose

- Trehalose

- Turbinado sugar

Watch out for items that list any form of sugar in the first few ingredients.

Glycemic Index

The glycemic index ranks carbohydrates on a scale from 0 to 100 based on how quickly and how much they raise blood sugar levels after eating. Foods with a high glycemic index, like white bread, are rapidly digested and cause substantial fluctuations in blood sugar. Foods with a low glycemic index, like whole oats, are digested more slowly, prompting a more gradual rise in blood sugar.

- Low-glycemic foods have a rating of 55 or less.

- Medium-level foods have a glycemic index of 56-69.

- High-glycemic foods are rated 70-100.

The University of Sydney in Australia maintains a searchable database of foods and their corresponding glycemic indices 11.

Eating many high-glycemic-index foods – which cause powerful spikes in blood sugar – can lead to an increased risk for type 2 diabetes 12, heart disease 13, 14 and overweight 15, 16, 17. There is also preliminary work linking high-glycemic diets to age-related macular degeneration 18, ovulatory infertility 19 and colorectal cancer 20.

- Foods with a low glycemic index have been shown to help control type 2 diabetes and improve weight loss.

- A 2014 review of studies researching carbohydrate quality and chronic disease risk showed that low-glycemic-index diets may offer anti-inflammatory benefits 21.

Many factors can affect a food’s glycemic index, including the following:

- Processing: Grains that have been milled and refined—removing the bran and the germ—have a higher glycemic index than minimally processed whole grains.

- Physical form: Finely ground grain is more rapidly digested than coarsely ground grain. This is why eating whole grains in their “whole form” like brown rice or oats can be healthier than eating highly processed whole grain bread.

- Fiber content: High-fiber foods don’t contain as much digestible carbohydrate, so it slows the rate of digestion and causes a more gradual and lower rise in blood sugar 22.

- Ripeness: Ripe fruits and vegetables tend to have a higher glycemic index than un-ripened fruit.

- Fat content and acid content: Meals with fat or acid are converted more slowly into sugar.

Numerous epidemiologic studies have shown a positive association between higher dietary glycemic index and increased risk of type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease. However, the relationship between glycemic index and body weight is less well studied and remains controversial.

Glycemic Load

One thing that a food’s glycemic index does not tell us is how much digestible carbohydrate – the total amount of carbohydrates excluding fiber – it delivers. That’s why researchers developed a related way to classify foods that takes into account both the amount of carbohydrate in the food in relation to its impact on blood sugar levels. This measure is called the glycemic load 23, 24.

In animals and in short-term human studies, a high intake of carbohydrates with a high glycemic index produced greater insulin resistance than did the intake of low-glycemic-index carbohydrates 24. In large prospective epidemiologic studies, both the glycemic index and the glycemic load (the glycemic index multiplied by the amount of carbohydrate) of the overall diet have been associated with a greater risk of type 2 diabetes in both men and women 24. Conversely, a higher intake of cereal fiber has been consistently associated with lower diabetes risk. In diabetic patients, evidence from medium-term studies suggests that replacing high-glycemic-index carbohydrates with a low-glycemic-index forms will improve glycemic control and, among persons treated with insulin, will reduce hypoglycemic episodes. These dietary changes, which can be made by replacing products made with white flour and potatoes with whole-grain, minimally refined cereal products, have also been associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease and can be an appropriate component of recommendations for an overall healthy diet.

A food’s glycemic load is determined by multiplying its glycemic index by the amount of carbohydrate the food contains.

The glycemic load has been used to study whether or not high-glycemic load diets are associated with increased risks for type 2 diabetes risk and cardiac events. In a large meta-analysis of 24 prospective cohort studies, researchers concluded that people who consumed lower-glycemic load diets were at a lower risk of developing type 2 diabetes than those who ate a diet of higher-glycemic load foods 25. A similar type of meta-analysis concluded that higher-glycemic load diets were also associated with an increased risk for coronary heart disease events 26.

In general, a glycemic load of 20 or more is high, 11 to 19 is medium, and 10 or under is low. Here is a listing of low, medium, and high glycemic load foods. For good health, choose foods that have a low or medium glycemic load, and limit foods that have a high glycemic load.

Low glycemic load (10 or under)

- Bran cereals

- Apple

- Orange

- Kidney beans

- Black beans

- Lentils

- Wheat tortilla

- Skim milk

- Cashews

- Peanuts

- Carrots

Medium glycemic load (11-19)

- Pearled barley: 1 cup cooked

- Brown rice: 3/4 cup cooked

- Oatmeal: 1 cup cooked

- Bulgur: 3/4 cup cooked

- Rice cakes: 3 cakes

- Whole grain breads: 1 slice

- Whole-grain pasta: 1 1/4 cup cooked

High glycemic load (20+)

- Baked potato

- French fries

- Refined breakfast cereal: 1 oz

- Sugar-sweetened beverages: 12 oz

- Candy bars: 1 2-oz bar or 3 mini bars

- Couscous: 1 cup cooked

- White basmati rice: 1 cup cooked

- White-flour pasta: 1 1/4 cup cooked

Summary

Carbohydrates are a nutritional energy source found in many foods and are an essential part of a healthy diet — as long as you stick to the good ones. You can assess carbohydrates quality based on these 4 factors:

- Dietary fiber;

- Glycemic index (how fast a food makes blood sugar rise);

- Whole-grain content; and

- Structure (intact versus milled or pulverized).

Here’s how to make healthy carbohydrates work in a balanced diet:

- Emphasize fiber-rich fruits and vegetables. Aim for whole fresh, frozen and canned fruits and vegetables without added sugar. Other options are fruit juices and dried fruits, which are concentrated sources of natural sugar and therefore have more calories. Whole fruits and vegetables also add fiber, water and bulk, which help you feel fuller on fewer calories.

- Choose whole grains. Whole grains are better sources than refined grains of fiber and other important nutrients, such as B vitamins. Refined grains go through a process that strips out parts of the grain — along with some of the nutrients and fiber.

- Stick to low-fat dairy products. Milk, cheese, yogurt and other dairy products are good sources of calcium and protein, plus many other vitamins and minerals. Consider the low-fat versions, to help limit calories and saturated fat. And beware of dairy products that have added sugar.

- Eat more legumes. Legumes — which include beans, peas and lentils — are among the most versatile and nutritious foods available. They are typically low in fat and high in folate, potassium, iron and magnesium, and they contain beneficial fats and fiber. Legumes are a good source of protein and can be a healthy substitute for meat, which has more saturated fat and cholesterol.

- Limit added sugars. Added sugar probably isn’t harmful in small amounts. But there’s no health advantage to consuming any amount of added sugar. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends that less than 10 percent of calories you consume every day come from added sugar.

In general, increase in the consumption of refined or processed foods and liquid carbohydrates or alcohol were positively associated with weight gain, whereas increase in the consumption of unprocessed foods such as whole grains, fruits, nuts, and vegetables would lead you to weight loss. So choose your carbohydrates wisely. Limit foods with added sugars and refined grains, such as sugary drinks, desserts and candy, which are packed with calories but low in nutrition. Instead, go for fruits, vegetables and whole grains.

References- Maton, Anthea; Jean Hopkins; Charles William McLaughlin; Susan Johnson; Maryanna Quon Warner; David LaHart; Jill D. Wright (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. pp. 52–59. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.

- Harvard University, Harvard School of Public Health. Carbohydrates. https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/carbohydrates/

- Optimal diets for prevention of coronary heart disease. Hu FB, Willett WC. JAMA. 2002 Nov 27; 288(20):2569-78. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12444864/

- Mozaffarian D, Hao T, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Hu FB. Changes in Diet and Lifestyle and Long-Term Weight Gain in Women and Men. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;364(25):2392-2404. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1014296. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3151731/

- Glycaemic response to foods: impact on satiety and long-term weight regulation. Bornet FR, Jardy-Gennetier AE, Jacquet N, Stowell J. Appetite. 2007 Nov; 49(3):535-53. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17610996/

- Rolls BJ, Roe LS, Beach AM, Kris-Etherton PM. Provision of foods differing in energy density affects long-term weight loss. Obes Res. 2005;13:1052–60. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15976148

- Ello-Martin JA, Roe LS, Ledikwe JH, Beach AM, Rolls BJ. Dietary energy density in the treatment of obesity: a year-long trial comparing 2 weight-loss diets. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1465–77. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2018610/

- Ledikwe JH, Rolls BJ, Smiciklas-Wright H, et al. Reductions in dietary energy density are associated with weight loss in overweight and obese participants in the PREMIER trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:1212–21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17490955

- Sugar-sweetened beverages, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease risk. Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després JP, Hu FB. Circulation. 2010 Mar 23; 121(11):1356-64. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20308626/

- Diabetes Care 2008 Dec; 31(12): 2281-2283. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc08-1239. International Tables of Glycemic Index and Glycemic Load Values: 2008. http://care.diabetesjournals.org/content/31/12/2281.full

- University of Sydney in Australia. Glycemic Index Database. http://glycemicindex.com/

- de Munter JS, Hu FB, Spiegelman D, Franz M, van Dam RM. Whole grain, bran, and germ intake and risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study and systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e261. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17760498

- Beulens JW, de Bruijne LM, Stolk RP, et al. High dietary glycemic load and glycemic index increase risk of cardiovascular disease among middle-aged women: a population-based follow-up study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:14-21. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17601539

- Halton TL, Willett WC, Liu S, et al. Low-carbohydrate-diet score and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1991-2002. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17093250

- Anderson JW, Randles KM, Kendall CW, Jenkins DJ. Carbohydrate and fiber recommendations for individuals with diabetes: a quantitative assessment and meta-analysis of the evidence. J Am Coll Nutr. 2004;23:5-17. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14963049

- Ebbeling CB, Leidig MM, Feldman HA, Lovesky MM, Ludwig DS. Effects of a low-glycemic load vs low-fat diet in obese young adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2007;297:2092-102. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17507345

- Maki KC, Rains TM, Kaden VN, Raneri KR, Davidson MH. Effects of a reduced-glycemic-load diet on body weight, body composition, and cardiovascular disease risk markers in overweight and obese adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:724-34. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17344493

- Chiu CJ, Hubbard LD, Armstrong J, et al. Dietary glycemic index and carbohydrate in relation to early age-related macular degeneration. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;83:880-6. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16600942

- Chavarro JE, Rich-Edwards JW, Rosner BA, Willett WC. A prospective study of dietary carbohydrate quantity and quality in relation to risk of ovulatory infertility. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63:78-86. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17882137

- Higginbotham S, Zhang ZF, Lee IM, et al. Dietary glycemic load and risk of colorectal cancer in the Women’s Health Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2004;96:229-33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14759990

- Buyken, AE, Goletzke, J, Joslowski, G, Felbick, A, Cheng, G, Herder, C, Brand-Miller, JC. Association between carbohydrate quality and inflammatory markers: systematic review of observational and interventional studies. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition Am J Clin Nutr. 99(4): 2014;813-33. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24552752

- AlEssa H, Bupathiraju S, Malik V, Wedick N, Campos H, Rosner B, Willett W, Hu FB. Carbohydrate quality measured using multiple quality metrics is negatively associated with type 2 diabetes. Circulation. 2015; 1-31:A:20. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/131/Suppl_1/A20.short

- Liu S, Willett WC. Dietary glycemic load and atherothrombotic risk. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2002;4:454-61. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12361493

- Willett W, Manson J, Liu S. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and risk of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:274S-80S. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12081851

- Livesey G, Taylor R, Livesey H, Liu S. Is there a dose-response relation of dietary glycemic load to risk of type 2 diabetes? Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:584-96. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23364021

- Mirrahimi A, de Souza RJ, Chiavaroli L, et al. Associations of glycemic index and load with coronary heart disease events: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohorts. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1:e000752. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23316283