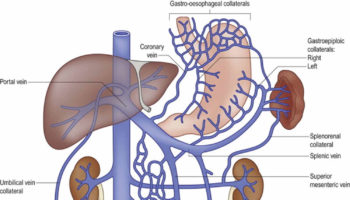

Iliac artery

The abdominal aorta descends to the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra (lumbar spine L4) where it divides into two common iliac arteries to form the right and left common iliac arteries and the small median sacral artery. These arteries carry blood to the pelvis and lower limbs. The common iliac arteries travel along the inner surface of the ilium, descending posterior to the cecum and sigmoid colon. At the level of the lumbosacral joint, each common iliac divides to form an internal iliac artery and an external iliac artery.

The internal iliac arteries enter the pelvic cavity and supply the urinary bladder, internal and external walls of the pelvis, external genitalia, and medial side of the thigh. The major branches of the internal iliac artery are the superior gluteal, internal pudendal, obturator, and lateral sacral arteries. In females, these vessels also supply the uterus and vagina.

The external iliac arteries supply blood to the lower limbs, and they are much larger in diameter than the internal iliac arteries. The external iliac artery crosses the surface of the iliopsoas and penetrates the abdominal wall, exiting the abdomen between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic symphysis. It

emerges on the anteromedial surface of the thigh as the femoral artery. The femoral artery continue into the leg to become the popliteal artery behind the knee, and the anterior and posterior tibial arteries in the legs.

Figure 1. Origin of Common Iliac and Internal and External Iliac Arteries

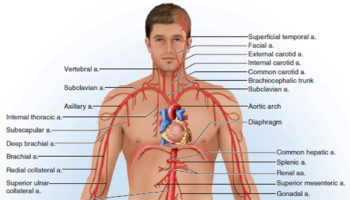

Internal iliac artery branches

The internal iliac artery divides into anterior and posterior trunks at the level of the superior border of the greater sciatic foramen.

Branches from the posterior trunk contribute to the supply of the lower posterior abdominal wall, the posterior pelvic wall, and the gluteal region.

Branches from the anterior trunk supply the pelvic viscera, the perineum, the gluteal region, the adductor region of the thigh, and, in the fetus, the placenta.

Figure 2. Internal iliac artery branches

Posterior trunk of the Internal Iliac artery

Branches o f the posterior trunk of the internal iliac artery are the iliolumbar artery, the lateral sacral artery, and the superior gluteal artery (Figure 2).

- The iliolumbar artery ascends laterally back out of the pelvic inlet and divides into a lumbar branch and an iliac branch. The lumbar branch contributes to the supply of the posterior abdominal wall, psoas and quadratus lumborum muscles, and cauda equina, via a small spinal branch that passes through the intervertebral foramen between L5 and SI (sacroiliac). The iliac branch passes laterally into the iliac fossa to supply muscle and bone.

- The lateral sacral arteries, usually two, originate from the posterior division of the internal iliac artery and course medially and inferiorly along the posterior pelvic wall. They give rise to branches that pass into the anterior sacral foramina to supply related bone and soft tissues, structures in the vertebral (sacral) canal, and skin and muscle posterior to the sacrum.

- The superior gluteal artery is the largest branch of the internal iliac artery and is the terminal continuation of the posterior trunk. It courses posteriorly, usually passing between the lumbosacral trunk and anterior ramus of S l , to leave the pelvic cavity through the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscle and enter the gluteal region of the lower limb. This vessel makes a substantial contribution to the blood supply of muscles and skin in the gluteal region and also supplies branches to adj acent muscles and bones of the pelvic walls.

Anterior trunk of the Internal Iliac artery

Branches of the anterior trunk of the internal iliac artery include the superior vesical artery, the umbilical artery, the inferior vesical artery, the middle rectal artery, the uterine artery, the vaginal artery, the obturator artery, the internal pudendal artery, and the inferior gluteal artery (Figure 2).

- The first branch of the anterior trunk is the umbilical artery, which gives origin to the superior vesical artery and then travels forward just inferior to the margin of the pelvic inlet. Anteriorly, the vessel leaves the pelvic cavity and ascends on the internal aspect of the anterior abdominal wall to reach the umbilicus. In the fetus, the umbilical artery is large and carries blood from the fetus to the placenta. After birth, the vessel closes distally to the origin of the superior vesical artery and eventually becomes a solid fibrous cord. On the anterior abdominal wall, the cord raises a fold of peritoneum termed the medial umbilical fold. The fibrous remnant of the umbilical artery itself is the medial umbilical ligament.

- The superior vesical artery normally originates from the root of the umbilical artery and courses medially and inferiorly to supply the superior aspect of the bladder and distal parts of the ureter. In men, it also may give rise to an artery that supplies the ductus deferens.

- The inferior vesical artery occurs in men and supplies branches to the bladder, ureter, seminal vesicle, and prostate. The vaginal artery in women is the equivalent of the inferior vesical artery in men and, descending to the vagina, supplies branches to the vagina and to adjacent parts of the bladder and rectum.

- The middle rectal artery courses medially to supply the rectum. The vessel anastomoses with the superior rectal artery, which originates from the inferior mesenteric artery in the abdomen, and the inferior rectal artery, which originates from the internal pudendal artery in the perineum.

- The obturator artery courses anteriorly along the pelvic wall and leaves the pelvic cavity via the obturator canal. Together with the obturator nerve, above, and obturator vein, below, it enters and supplies the adductor region of the thigh.

- The internal pudendal artery courses inferiorly from its origin in the anterior trunk and leaves the pelvic cavity through the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle. In association with the pudendal nerve on its medial side, the vessel passes laterally to the ischial spine and then through the lesser sciatic foramen to enter the perineum. The internal pudendal artery is the main artery of the perineum. Among the structures it supplies are the erectile tissues of the clitoris and the penis.

- The inferior gluteal artery is a large terminal branch of the anterior trunk of the internal iliac artery. It passes between the anterior rami Sl and S2 or S2 and S3 of the sacral plexus and leaves the pelvic cavity through the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle. It enters and contributes to the blood supply of the gluteal region and anastomoses with a network of vessels around the hip joint.

Iliac artery aneurysm

An aneurysm is an abnormal widening or ballooning of a part of an artery due to weakness in the wall of the blood vessel 1.

Arteries have thick walls to withstand normal blood pressure. However, certain medical problems, genetic conditions, and trauma can damage or injure artery walls. The force of blood pushing against the weakened or injured walls can cause an aneurysm.

Most aneurysms occur in the aorta, the main artery that carries oxygen-rich blood from the heart to the body 2. The aorta goes through the chest and abdomen.

An aneurysm that occurs in the chest portion of the aorta is called a thoracic aortic aneurysm. An aneurysm that occurs in the abdominal portion of the aorta is called an abdominal aortic aneurysm. About 13,000 Americans die each year from aortic aneurysms. Most of the deaths result from rupture or dissection.

Aneurysms also can occur in other arteries (e.g. iliac artery aneurysm), but these types of aneurysm are rare.

Isolated iliac artery aneurysms are rare clinical conditions 3. Internal iliac artery aneurysms make up less than 0.5% of all intra-abdominal aneurysms 4. Because of their rarity and their depth in the pelvis they are difficult to diagnose and tend to present late with symptoms from compression (urological and neurological symptoms, constipation, leg oedema, iliofemoral thrombosis, expansion, fistulation and rupture 5, 6.

Common iliac artery aneurysm often occurs in conjunction with an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), which extends into one or both of the common iliac arteries in 20% to 30% of patients 7. Unilateral aortoiliac aneurysms are present in 43%, and bilateral common iliac artery aneurysms in 11% of patients with intact abdominal aortic aneurysm 8.

Because iliac artery aneurysms are difficult to detect and treat and consequently have been associated with a high rate of mortality 9. The natural history of these aneurysms is of expansion and eventual rupture. Rupture is associated with a 58% mortality 10. Rupture of iliac artery aneurysms is reported to carry a 50% to 70% mortality rate and because the incidence of rupture is as high as 50%, it is imperative that diagnosis be early and intervention prompt 11. The recommended therapy for this condition is still surgical excision 12, although newer treatments such as intravascular stenting are being performed. Early intervention with the proper surgical technique can reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with this condition.

Surgical treatment poses a formidable technical challenge 6, 10 with a mortality of 10% even in cases treated electively 5. Percutaneous coil embolization to thrombose the sac may obviate the need for an open procedure, but only a few case reports are available 6. If there is no proximal neck, stent grafts can be used to occlude the aneurysm origin 4. Development of venous thrombosis after embolization of an internal iliac artery aneurysm has been reported previously—the result of continued pressure from the embolized aneurysm 5. In a separate reported case, a patient was treated by venous thrombectomy, venous stenting and arterial coil embolization 13.

Early diagnosis and treatment can help prevent rupture and dissection. However, aneurysms can develop and grow large before causing any symptoms. Thus, people who are at high risk for aneurysms can benefit from early, routine screening.

An aneurysm can grow large and rupture (burst) or dissect. A rupture causes dangerous bleeding inside the body. A dissection is a split in one or more layers of the artery wall. The split causes bleeding into and along the layers of the artery wall.

Both rupture and dissection often are fatal.

When to Contact a Medical Professional

Call your provider if you develop a lump on your body, whether or not it is painful and throbbing.

With an aortic aneurysm, go to the emergency room or call your local emergency number if you have pain in your belly or back that is very bad or does not go away.

With a brain aneurysm, go to the emergency room or call the local emergency number if you have a sudden or severe headache, especially if you also have nausea, vomiting, seizures, or any other nervous system symptom.

Prevention of an aneursym

The best way to prevent an aneurysm is to avoid the factors that put you at higher risk for one. You can’t control all aneurysm risk factors, but lifestyle changes can help you lower some risks.

Controlling high blood pressure may help prevent some aneurysms. Follow a healthy diet, get regular exercise, and keep your cholesterol at a healthy level to also help prevent aneurysms or their complications.

DO NOT smoke. If you do smoke, quitting will lower your risk of an aneurysm.

Screening for Aneurysms

Although you may not be able to prevent an aneurysm, early diagnosis and treatment can help prevent rupture and dissection.

Aneurysms can develop and grow large before causing any signs or symptoms. Thus, people who are at high risk for aneurysms may benefit from early, routine screening.

Your doctor may recommend routine screening if you’re:

- A man between the ages of 65 and 75 who has ever smoked

- A man or woman between the ages of 65 and 75 who has a family history of aneurysms

If you’re at risk, but not in one of these high-risk groups, ask your doctor whether screening will benefit you.

Types of Aneurysms

Aortic Aneurysms

The two types of aortic aneurysm are abdominal aortic aneurysm and thoracic aortic aneurysm. Some people have both types.

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

An aneurysm that occurs in the abdominal portion of the aorta is called an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). Most aortic aneurysms are abdominal aortic aneurysms.

These aneurysms are found more often now than in the past because of computed tomography scans, or CT scans, done for other medical problems.

Small abdominal aortic aneurysms rarely rupture. However, abdominal aortic aneurysms can grow very large without causing symptoms. Routine checkups and treatment for an abdominal aortic aneurysm can help prevent growth and rupture.

Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms

An aneurysm that occurs in the chest portion of the aorta (above the diaphragm, a muscle that helps you breathe) is called a thoracic aortic aneurysm.

Thoracic aortic aneurysms don’t always cause symptoms, even when they’re large. Only half of all people who have thoracic aortic aneurysms notice any symptoms. Thoracic aortic aneurysms are found more often now than in the past because of chest CT scans done for other medical problems.

With a common type of thoracic aortic aneurysm, the walls of the aorta weaken and a section close to the heart enlarges. As a result, the valve between the heart and the aorta can’t close properly. This allows blood to leak back into the heart.

A less common type of thoracic aortic aneurysm can develop in the upper back, away from the heart. A thoracic aortic aneurysm in this location may result from an injury to the chest, such as from a car crash.

Figure 3. Aortic aneurysm

Other Types of Aneurysms

Brain Aneurysms

Aneurysms in the arteries of the brain are called cerebral aneurysms or brain aneurysms. Brain aneurysms also are called berry aneurysms because they’re often the size of a small berry.

Most brain aneurysms cause no symptoms until they become large, begin to leak blood, or rupture (burst). A ruptured brain aneurysm can cause a stroke.

Figure 4. Brain aneurysm

Peripheral Aneurysms

Aneurysms that occur in arteries other than the aorta and the brain arteries are called peripheral aneurysms. Common locations for peripheral aneurysms include the popliteal, femoral and carotid arteries.

The popliteal arteries run down the back of the thighs, behind the knees. The femoral arteries are the main arteries in the groin. The carotid arteries are the two main arteries on each side of your neck.

Peripheral aneurysms aren’t as likely to rupture or dissect as aortic aneurysms. However, blood clots can form in peripheral aneurysms. If a blood clot breaks away from the aneurysm, it can block blood flow through the artery.

If a peripheral aneurysm is large, it can press on a nearby nerve or vein and cause pain, numbness, or swelling.

Causes of an aneurysm

The force of blood pushing against the walls of an artery combined with damage or injury to the artery’s walls can cause an aneurysm.

It is not clear exactly what causes aneurysms. Some aneurysms are present at birth (congenital). Defects in some parts of the artery wall may be a cause.

Common locations for aneurysms include:

- Major artery from the heart (the aorta)

- Brain (cerebral aneurysm)

- Behind the knee in the leg (popliteal artery aneurysm)

- Intestine (mesenteric artery aneurysm)

- Artery in the spleen (splenic artery aneurysm)

High blood pressure, high cholesterol, and cigarette smoking may raise your risk for certain types of aneurysms 2. High blood pressure is thought to play a role in abdominal aortic aneurysms. Atherosclerotic disease (cholesterol buildup in arteries) may also lead to the formation of some aneurysms 2.

Pregnancy is often linked to the formation and rupture of splenic artery aneurysms.

A family history of aneurysms also may play a role in causing aortic aneurysms.

In addition to the factors above, certain genetic conditions may cause thoracic aortic aneurysms. Examples of these conditions include Marfan syndrome, Loeys-Dietz syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (the vascular type), and Turner syndrome.

These genetic conditions can weaken the body’s connective tissues and damage the aorta. People who have these conditions tend to develop aneurysms at a younger age than other people. They’re also at higher risk for rupture and dissection.

Trauma, such as a car accident, also can damage the walls of the aorta and lead to thoracic aortic aneurysms.

Researchers continue to look for other causes of aortic aneurysms. For example, they’re looking for genetic mutations (changes in the genes) that may contribute to or cause aneurysms.

Who Is at Risk for an Aneurysm ?

Certain factors put you at higher risk for an aortic aneurysm. These factors include:

- Male gender. Men are more likely than women to have aortic aneurysms.

- Age. The risk for abdominal aortic aneurysms increases as you get older. These aneurysms are more likely to occur in people who are aged 65 or older.

- Smoking. Smoking can damage and weaken the walls of the aorta.

- A family history of aortic aneurysms. People who have family histories of aortic aneurysms are at higher risk for the condition, and they may have aneurysms before the age of 65.

- A history of aneurysms in the arteries of the legs.

- Certain diseases and conditions that weaken the walls of the aorta. Examples include high blood pressure and atherosclerosis.

Having a bicuspid aortic valve can raise the risk of having a thoracic aortic aneurysm. A bicuspid aortic valve has two leaflets instead of the typical three.

Car accidents or trauma also can injure the arteries and increase the risk for aneurysms.

If you have any of these risk factors, talk with your doctor about whether you need screening for aneurysms.

Symptoms and signs of an Aneurysm

The signs and symptoms of an aneurysm depend on the type and location of the aneurysm. Signs and symptoms also depend on whether the aneurysm has ruptured (burst) or is affecting other parts of the body. If the aneurysm occurs near the body’s surface, pain and swelling with a throbbing lump is often seen.

Aneurysms can develop and grow for years without causing any signs or symptoms. They often don’t cause signs or symptoms until they rupture, grow large enough to press on nearby body parts, or block blood flow.

Aneurysms in the body or brain often cause no symptoms. Aneurysms in the brain may expand without breaking open (rupturing). The expanded aneurysm may press on nerves and cause double vision, dizziness, or headaches. Some aneurysms may cause ringing in the ears.

If an aneurysm ruptures, pain, low blood pressure, a rapid heart rate, and lightheadedness may occur. When a brain aneurysm ruptures, there is a sudden severe headache that some people say is the “worst headache of my life.” The risk of death after a rupture is high.

Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms

Most abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) develop slowly over years. They often don’t cause signs or symptoms unless they rupture. If you have an abdominal aortic aneurysm, your doctor may feel a throbbing mass while checking your abdomen.

When symptoms are present, they can include:

- A throbbing feeling in the abdomen

- Deep pain in your back or the side of your abdomen

- Steady, gnawing pain in your abdomen that lasts for hours or days

If an abdominal aortic aneurysm ruptures, symptoms may include sudden, severe pain in your lower abdomen and back; nausea (feeling sick to your stomach) and vomiting; constipation and problems with urination; clammy, sweaty skin; light-headedness; and a rapid heart rate when standing up.

Internal bleeding from a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm can send you into shock. Shock is a life-threatening condition in which blood pressure drops so low that the brain, kidneys, and other vital organs can’t get enough blood to work well. Shock can be fatal if it’s not treated right away.

Thoracic Aortic Aneurysms

A thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) may not cause symptoms until it dissects or grows large. If you have symptoms, they may include:

- Pain in your jaw, neck, back, or chest

- Coughing and/or hoarseness

- Shortness of breath and/or trouble breathing or swallowing

A dissection is a split in one or more layers of the artery wall. The split causes bleeding into and along the layers of the artery wall.

If a thoracic aortic aneurysm ruptures or dissects, you may feel sudden, severe, sharp or stabbing pain starting in your upper back and moving down into your abdomen. You may have pain in your chest and arms, and you can quickly go into shock.

If you have any symptoms of thoracic aortic aneurysm or aortic dissection, call your local emergency number. If left untreated, these conditions may lead to organ damage or death.

How Is an Aneurysm Diagnosed ?

If you have an aortic aneurysm but no symptoms, your doctor may find it by chance during a routine physical exam. More often, doctors find aneurysms during tests done for other reasons, such as chest or abdominal pain.

If you have an abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), your doctor may feel a throbbing mass in your abdomen. A rapidly growing aneurysm about to rupture (burst) can be tender and very painful when pressed. If you’re overweight or obese, it may be hard for your doctor to feel even a large abdominal aortic aneurysm.

If you have an abdominal aortic aneurysm, your doctor may hear rushing blood flow instead of the normal whooshing sound when listening to your abdomen with a stethoscope.

Specialists Involved

Your primary care doctor may refer you to a cardiothoracic or vascular surgeon for diagnosis and treatment of an aortic aneurysm.

A cardiothoracic surgeon does surgery on the heart, lungs, and other organs and structures in the chest, including the aorta. A vascular surgeon does surgery on the aorta and other blood vessels, except those of the heart and brain.

Diagnostic Tests and Procedures

To diagnose and study an aneurysm, your doctor may recommend one or more of the following tests.

- Ultrasound and Echocardiography

Ultrasound and echocardiography (echo) are simple, painless tests that use sound waves to create pictures of the structures inside your body. These tests can show the size of an aortic aneurysm, if one is found.

- Computed Tomography Scan

A computed tomography scan, or CT scan, is a painless test that uses x rays to take clear, detailed pictures of your organs.

During the test, your doctor will inject dye into a vein in your arm. The dye makes your arteries, including your aorta, visible on the CT scan pictures.

Your doctor may recommend this test if he or she thinks you have an abdominal aortic aneurysm or a thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA). A CT scan can show the size and shape of an aneurysm. This test provides more detailed pictures than an ultrasound or echo.

Figure 5. CT scan image shows significant aneurismal dilatation of abdominal aorta and both common iliac arteries.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) uses magnets and radio waves to create pictures of the organs and structures in your body. This test works well for detecting aneurysms and pinpointing their size and exact location.

- Angiography

Angiography is a test that uses dye and special x rays to show the insides of your arteries. This test shows the amount of damage and blockage in blood vessels.

Aortic angiography shows the inside of your aorta. The test may show the location and size of an aortic aneurysm.

How Is an Aneurysm Treated ?

Aortic aneurysms are treated with medicines and surgery. Small aneurysms that are found early and aren’t causing symptoms may not need treatment. Other aneurysms need to be treated.

The goals of treatment may include:

- Preventing the aneurysm from growing

- Preventing or reversing damage to other body structures

- Preventing or treating a rupture or dissection

- Allowing you to continue doing your normal daily activities

Treatment for an aortic aneurysm is based on its size. Your doctor may recommend routine testing to make sure an aneurysm isn’t getting bigger. This method usually is used for aneurysms that are smaller than 5 centimeters (about 2 inches) across.

How often you need testing (for example, every few months or every year) is based on the size of the aneurysm and how fast it’s growing. The larger it is and the faster it’s growing, the more often you may need to be checked.

Medicines

If you have an aortic aneurysm, your doctor may prescribe medicines before surgery or instead of surgery. Medicines are used to lower blood pressure, relax blood vessels, and lower the risk that the aneurysm will rupture (burst). Beta blockers and calcium channel blockers are the medicines most commonly used.

Surgery

Your doctor may recommend surgery if your aneurysm is growing quickly or is at risk of rupture or dissection.

The two main types of surgery to repair aortic aneurysms are open abdominal or open chest repair and endovascular repair.

Open Abdominal or Open Chest Repair

The standard and most common type of surgery for aortic aneurysms is open abdominal or open chest repair. This surgery involves a major incision (cut) in the abdomen or chest.

General anesthesia is used during this procedure. The term “anesthesia” refers to a loss of feeling and awareness. General anesthesia temporarily puts you to sleep.

During the surgery, the aneurysm is removed. Then, the section of aorta is replaced with a graft made of material such as Dacron® or Teflon.® The surgery takes 3 to 6 hours; you’ll remain in the hospital for 5 to 8 days.

If needed, repair of the aortic heart valve also may be done during open abdominal or open chest surgery.

It often takes a month to recover from open abdominal or open chest surgery and return to full activity. Most patients make a full recovery.

Endovascular Repair

In endovascular repair, the aneurysm isn’t removed. Instead, a graft is inserted into the aorta to strengthen it. Surgeons do this type of surgery using catheters (tubes) inserted into the arteries; it doesn’t require surgically opening the chest or abdomen. General anesthesia is used during this procedure.

The surgeon first inserts a catheter into an artery in the groin (upper thigh) and threads it to the aneurysm. Then, using an x ray to see the artery, the surgeon threads the graft (also called a stent graft) into the aorta to the aneurysm.

The graft is then expanded inside the aorta and fastened in place to form a stable channel for blood flow. The graft reinforces the weakened section of the aorta. This helps prevent the aneurysm from rupturing.

The recovery time for endovascular repair is less than the recovery time for open abdominal or open chest repair. However, doctors can’t repair all aortic aneurysms with endovascular repair. The location or size of an aneurysm may prevent the use of a stent graft.

Figure 5. Endovascular Aneursym Repair

Note: The illustration shows the placement of a stent graft in an aortic aneurysm. In figure A, a catheter is inserted into an artery in the groin (upper thigh). The catheter is threaded to the abdominal aorta, and the stent graft is released from the catheter. In figure B, the stent graft allows blood to flow through the aneurysm.

- Aneurysm. Medline Plus, U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001122.htm[↩]

- Aneurysm. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/arm[↩][↩][↩]

- Nagarajan M, Chandrasekar P, Krishnan E, Muralidharan S. Repair of Iliac Artery Aneurysms by Endoluminal Grafting: The Systematic Approach of One Institution. Texas Heart Institute Journal. 2000;27(3):250-252. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC101075/[↩]

- Parry DJ, Kessel D, Scott DJ. Simplifying the internal iliac artery aneurysm. Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2001;83(5):302-308. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2503416/pdf/annrcse01633-0014.pdf[↩][↩]

- Su WT, Goldman KA, Riles TS, Rosen R. Deep venous thrombosis with pulmonary embolus after selective embolization of an internal iliac artery aneurysm. J Vasc Surg 1996;23: 152–5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8558731[↩][↩][↩]

- Secil M, Sarisoy HT, Hazan E, Goktay AY. Iliac artery aneurysm presenting with lower extremity deep vein thrombosis. J Emerg Med 2003;24: 65–7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12554043[↩][↩][↩]

- Malina M, Dirven M, Sonesson B, Resch T, Dias N, Ivancev K. Feasibility of a branched stent-graft in common iliac artery aneurysms. J Endovasc Ther. 2006;13:496–500. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16928164[↩]

- Hinchliffe RJ, Alric P, Rose D, Owen V, Davidson IR, Armon MP, et al. Comparison of morphologic features of intact and ruptured aneurysms of infrarenal abdominal aorta. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38:88–92. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12844095[↩]

- Natural history and management of iliac aneurysms. Richardson JW, Greenfield LJ. J Vasc Surg. 1988 Aug; 8(2):165-71. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3294450/[↩]

- Hollis HW Jr, Luethke JM, Yakes WF, Beitler AL. Percutaneous embolization of an internal iliac artery aneurysm: technical considerations and literature review. Vasc Intervent Radiol 1994;5: 449–57. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8054744[↩][↩]

- Brunkwall J, Hauksson H, Bengtsson H, Bergqvist D, Takolander R, Bergentz SE. Solitary aneurysms of the iliac arterial system: an estimate of their frequency of occurrence. J Vasc Surg 1989;10:381–4. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2795762[↩]

- Krajcer Z, Khoshnevis R, Leachman DR, Herman H. Endoluminal exclusion of an iliac artery aneurysm by Wallstent endoprosthesis and PTFE vascular graft. Texas Heart Institute Journal. 1997;24(1):11-14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC325391/pdf/thij00024-0021.pdf[↩]

- Rosenthal D, Matsuura JH, Jerius H, Clark MD. Iliofemoral venous thrombosis caused by compression of an internal iliac artery aneurysm: a minimally invasive treatment. J Endovasc Surg 1998;5: 142–5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9633959[↩]