Interstitial ectopic pregnancy

Interstitial pregnancy is an uncommon kind of ectopic pregnancy and is defined as a pregnancy in which the product of conception is implanted in the intramural portion of the fallopian tube 1. Interstitial pregnancy accounts for approximately 2–3% of ectopic pregnancies 2 and represent almost one-fifth of all deaths caused by ectopic pregnancies 3. Ectopic pregnancy occurs when the gestational sac implants itself outside the endometrial cavity, classified according to the place where it is inserted. The interstitial part of the fallopian tube, the proximal portion that lies within the muscular wall of the uterus is approximately 1–2 cm long, 0.7 mm wide and corresponds to the intramyometrial portion and has abundant blood supply fromthe uterine and ovarian vessels 4. Pregnancies at this location have an implantation lateral to the round ligament, with a thin layer of myometrium surrounding the sac (usually <5 mm) 5. Interstitial pregnancy being considered not viable, the location prevents the pregnancy from reaching term; however, it may progress beyond the first trimester as it is a very vascularized and distensible region 6. The important complications of interstitial pregnancy are uterine rupture and massive bleeding, which usually occur before 12 weeks of pregnancy.

Despite the well-known fact that the interstitial pregnancy and cornual pregnancy are two different entities, they are often used as synonyms and the medical literature includes references that use the terms cornual pregnancy and interstitial pregnancy interchangeably 7. However, it is important to differentiate and report these two entities separately as the clinical course and management differ markedly between cornual pregnancy and interstitial ectopic pregnancy 8.

Interstitial pregnancies tend to present relatively late at 7-12 weeks gestation due to myometrial distensibility and the specific symptoms and signs are often missing leading to significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges 9. Rupture can lead to massive hemorrhage leading to hypovolemic shock and often death.

In 2003, Chan et al 10 reported 36 cases of interstitial ectopic pregnancies with an emphasis on the pitfalls in the diagnosis and treatment of these cases. In this series, 41.7% of interstitial ectopics were misdiagnosed at the first presentation, where all but one were mistaken as intrauterine pregnancies. Rupture of interstitial pregnancy occurred in 40% of these women and in two cases, at an advanced gestation of 18-20 weeks. There was a median delay inthe diagnosis of 13 days (4-70 days). The most common diagnostic pitfall was intrauterine pregnancy, either viable or nonviable, where a third (33%) of the women underwent suction evacuation and a further 10% were either referred for or planned to have termination of pregnancy or suction evacuation 11.

Although ultrasound imaging has made great improvement over the last decades, diagnosing an interstitial pregnancy remains challenging and it is often misdiagnosed. As a result, 20% to 50% of the patients with an interstitial pregnancy present with a cornual rupture 12. Furthermore, there is a higher morbidity and mortality rate associated with interstitial pregnancy compared to other types of ectopic pregnancy. Possible causes include higher chance to misjudge the entity, the tendency to rupture later in pregnancy and the high vascularization of the cornual region, being vascularized from ovarian and uterine arterial branches, resulting in massive blood loss upon rupturing. In case of a heterotopic interstitial pregnancy, even more diagnostic challenges arise due to a normal rise in β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG) levels and the presence of the concomitant intrauterine pregnancy, which often falsely reassures the examiner 13.

A heterotopic pregnancy implies the coexistence of an intrauterine and an ectopic pregnancy. It occurs 1 in 30,000 naturally conceived pregnancies. However, the more frequent use of assisted reproductive technologies (ART), including ovulation-induction, intrauterine insemination (IUI), in vitro fertilization (IVF), and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), leads to a rise in both ectopic pregnancy as well as dizygotic twinning rates, consequently leads to an increase in incidence of heterotopic pregnancy to 1.5% in pregnancies after ART. Subsequently, the overall incidence of heterotopic pregnancy has risen to 1 in 3900 pregnancies 14. The risk is higher when more embryos are transferred or when a tubal infertility factor is present 15. Previous data suggest that women with a history of salpingectomy have an increased risk of developing an interstitial pregnancy after IVF 16. The incidence of heterotopic interstitial pregnancy after IVF is unknown, yet through calculation of combined incidences it can be estimated to be as high as 1 in 3600 IVF pregnancies 17.

The diagnosis is mainly based on the following ultrasound criteria: (i) empty uterine cavity; (ii) a gestation sac located in the intramyometrial portion of the tube continuously surrounded by the myometrial wall of the uterus; (iii) the interstitial line abuts the gestational sac and the lateral aspect of the uterine cavity 18.

Interstitial ectopic pregnancy treatment depends on gestational age, clinical picture, and surgical expertise. Although various approaches to treating interstitial pregnancy have been previously reported, the optimal treatment regimen has not been determined due to its rarity 19. The traditional treatment of interstitial pregnancy was surgery including hysterectomy and cornual resection by laparotomic or laparoscopic approaches. This may adversely affect subsequent pregnancies with the possibility of uterine rupture during subsequent pregnancies. Several medical treatments, such as local potassium chloride (KCl) injection and methotrexate (MTX) treatment, have been introduced with generally satisfactory results 20.

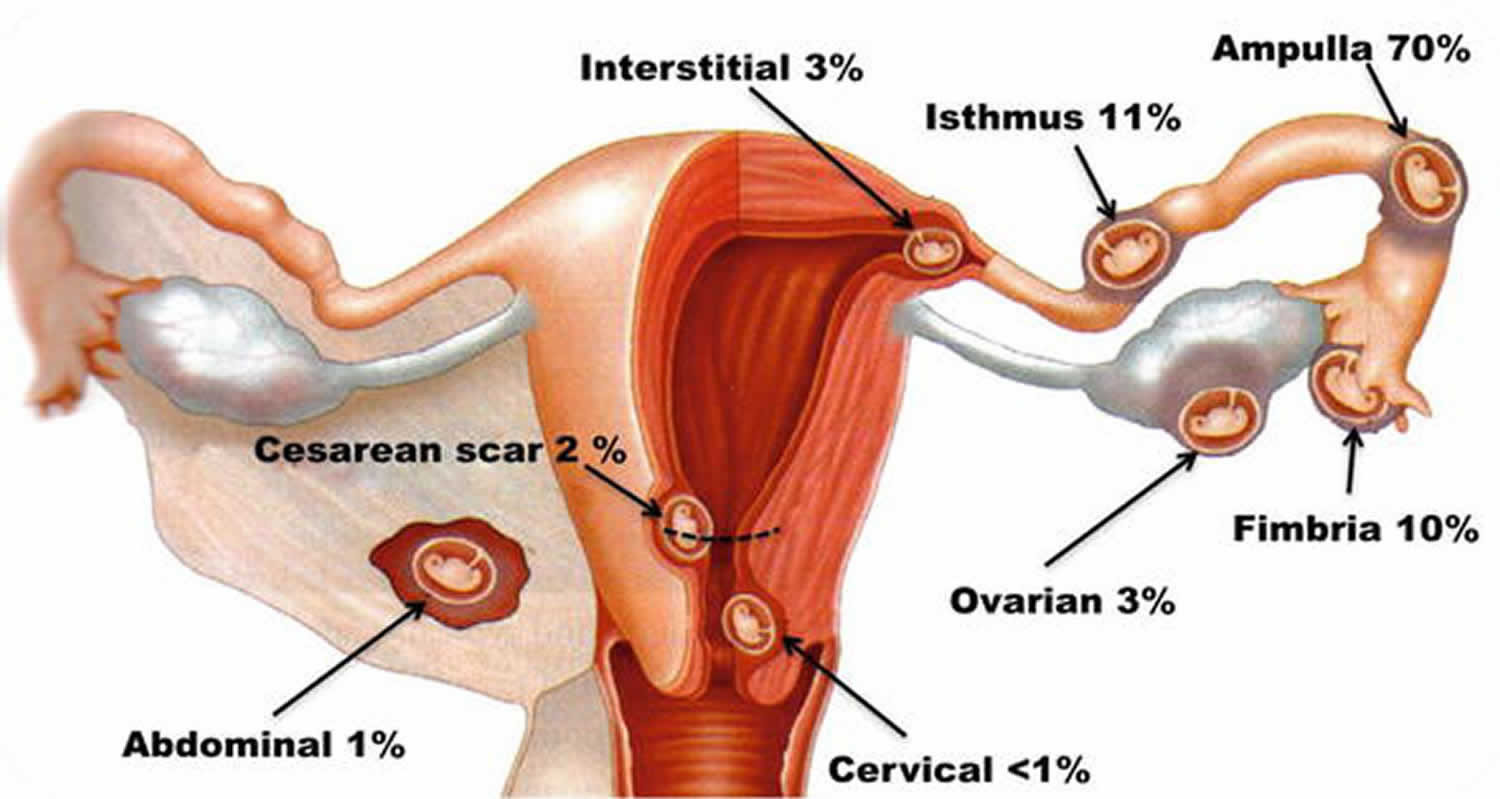

Incidence of non‐tubal ectopic pregnancy in all ectopic pregnancies:

- Cervical <1%

- Cesarean scar <6.1%

- Interstitial <2 -11%

- Cornual 2%

- Ovarian 1-6%

- Abdominal <0.9-1.4%

Figure 1. Interstitial pregnancy

Seek emergency medical help if you have any signs or symptoms of an ectopic pregnancy, including:

- Severe abdominal or pelvic pain accompanied by vaginal bleeding

- Extreme lightheadedness or fainting

- Shoulder pain

Interstitial pregnancy causes

Although the cause for interstitial pregnancies is not fully understood, several risk factors have been established, such as previous tubal surgery, previous salpingectomy, previous ectopic pregnancy, use of an intrauterine device, in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer (IVF-ET), ovulation induction, sexually transmitted disease, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), salpingitis, infertility and smoking 21. Recently, with the increasing incidence of in vitro fertilization (IVF) attempts or assisted reproductive technology (ART) procedures, the incidence of interstitial pregnancy is expected to increase.

Risk factors for interstitial ectopic pregnancy

Some things that make you more likely to have an ectopic pregnancy are:

- Previous ectopic pregnancy. If you’ve had this type of pregnancy before, you’re more likely to have another.

- Inflammation or infection. Sexually transmitted infections, such as gonorrhea or chlamydia, can cause inflammation in the tubes and other nearby organs, and increase your risk of an ectopic pregnancy.

- Fertility treatments. Some research suggests that women who have in vitro fertilization (IVF) or similar treatments are more likely to have an ectopic pregnancy. Infertility itself may also raise your risk.

- Tubal surgery. Surgery to correct a closed or damaged fallopian tube can increase the risk of an ectopic pregnancy.

- Choice of birth control. The chance of getting pregnant while using an intrauterine device (IUD) is rare. However, if you do get pregnant with an IUD in place, it’s more likely to be ectopic.

- Tubal ligation, a permanent method of birth control commonly known as “having your tubes tied,” also raises your risk, if you become pregnant after this procedure.

- Smoking. Cigarette smoking just before you get pregnant can increase the risk of an ectopic pregnancy. The more you smoke, the greater the risk.

Interstitial pregnancy symptoms

You may not notice any symptoms at first. However, some women who have an ectopic pregnancy have the usual early signs or symptoms of pregnancy — a missed period, breast tenderness and nausea.

If you take a pregnancy test, the result will be positive. Still, an ectopic pregnancy can’t continue as normal.

As the fertilized egg grows in the improper place, signs and symptoms become more noticeable.

Early warning of ectopic pregnancy

Often, the first warning signs of an ectopic pregnancy are light vaginal bleeding and pelvic pain.

If blood leaks from the fallopian tube, you may feel shoulder pain or an urge to have a bowel movement. Your specific symptoms depend on where the blood collects and which nerves are irritated.

Emergency symptoms

If the fertilized egg continues to grow in the fallopian tube, it can cause the tube to rupture. Heavy bleeding inside the abdomen is likely. Symptoms of this life-threatening event include extreme lightheadedness, fainting and shock.

Interstitial pregnancy complications

An ectopic pregnancy can cause your fallopian tube to burst open. Without treatment, the ruptured tube can lead to life-threatening bleeding.

Interstitial pregnancy diagnosis

Interstitial ectopic pregnancy is rare and challenging to diagnose and frequently constitute a medical emergency. Thus, prompt and effective treatment is important to avoid potentially catastrophic consequences such as massive hemorrhaging, hysterectomy, and death. The improved ultrasound technology widely used in early pregnancy assessment and high awareness of the possibility of ectopic pregnancy have contributed to earlier diagnosis of these pregnancies.

Pregnancy test

Your doctor will order the human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) blood test to confirm that you’re pregnant. Levels of this hormone increase during pregnancy. This blood test may be repeated every few days until ultrasound testing can confirm or rule out an ectopic pregnancy — usually about five to six weeks after conception.

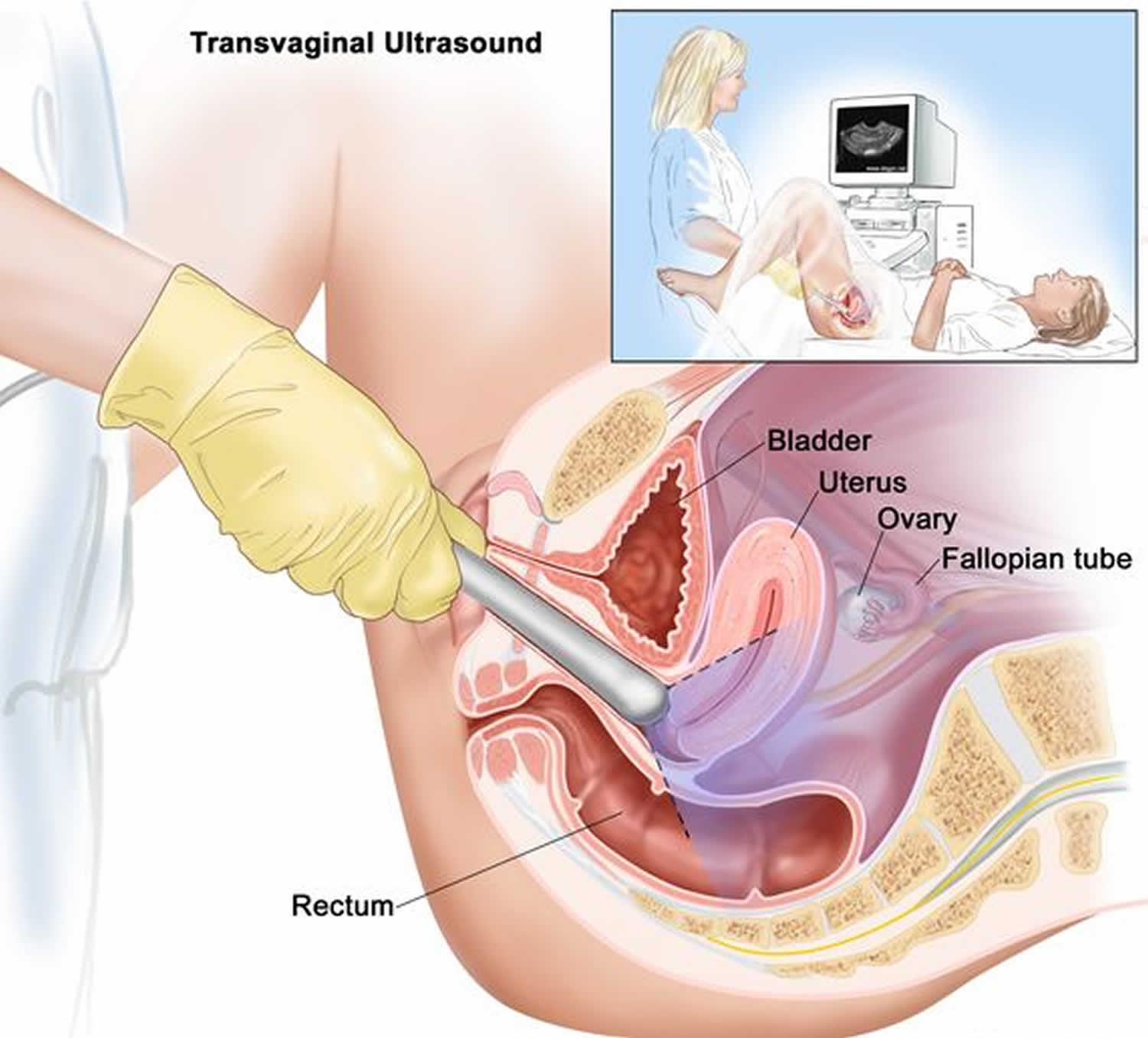

Ultrasound

A transvaginal ultrasound allows your doctor to see the exact location of your pregnancy. For this test, a wandlike device is placed into your vagina. It uses sound waves to create images of your uterus, ovaries and fallopian tubes, and sends the pictures to a nearby monitor.

The high-resolution transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasound criteria used for the diagnosis of interstitial pregnancy are 21:

- Empty uterine cavity;

- A gestational sac separate and at least 1 cm from the lateral edge of the uterine cavity or products of conception located outside of theendometrial cavity (sensitivity: 40%; specificity: 88%);

- Thin (<5 mm) myometrial layer surrounding the chorionic sac or products of conception (sensitivity40%; specificity: 98%);

- Interstitial line (echogenic line medial to gestational sac, sensitivity: 80%;specificity: 98%).

The most useful sonographic feature in diagnosing an interstitial pregnancy tends to be the thin myometrial layer surrounding the interstitial gestational sac. The eccentric localization can be difficult to distinguish from an eccentrically located intrauterine pregnancy 22. Another useful sign is the interstitial line sign, which is the presence of an uninterrupted, thin hyperechogenic line extending between the interstitial gestational sac and the endometrium, suggesting that the pregnancy is outside the endometrial cavity 22. The gestational sac is usually in the lateral portion of the uterus early in gestation, but in advanced interstitial pregnancy, it can be located above the uterine fundus and can be confused with an eccentric intrauterine pregnancy. The interstitial line had better sensitivity (80%) and specificity (98%) than eccentric gestational sac location (sensitivity, 40%;specificity, 88%) and myometrial thinning (sensitivity, 40%; speci-ficity, 93%) for the diagnosis of interstitial pregnancy 7.

Figure 2. Transvaginal ultrasound

Interstitial pregnancy treatment

Management options are determined by patient characteristics, including the gestational age, viability of the interstitial pregnancy, symptoms, and whether or not the interstitial pregnancy has ruptured.

Surgery is the primary treatment for most ovarian, interstitial, cornual, and abdominal pregnancies 23. Interstitial pregnancy has traditionally been treated using cornual resection or hysterectomy in the cases with severely damaged uteri 24. The surgery can be completed through laparoscopy or laparotomy, but laparotomy may be required for those with uterine rupture and hemoperitoneum 25. Hysteroscopic excision of interstitial pregnancies under laparoscopic visualization or ultrasound guidance has been described 26.

Improvements in the early detection of interstitial ectopic pregnancies, before rupture, have led to the utilization of possible conservative treatment options. For women who desire fertility preservation, conservative measures have become the first‐line approach. These options include administration (local or systemic) of various chemotherapeutic agents (including methotrexate, etoposide, actinomycin D, and cyclophosphamide) and endoscopic removal techniques (laparoscopy or hysteroscopy), alone or as adjuvant therapies, with or without hemostatic techniques (balloon tamponade, uterine artery ligation, cerclage, cervical stay sutures) 27.

Conservative measures may be attempted for selective interstitial or cornual pregnancies but carry a high risk of initial failure 24. Expectant management could be considered in case of an asymptomatic patient with a rather small interstitial pregnancy without cardiac activity 28 and declining β‐hCG levels 29. Its main advantage is the avoidance of potential adverse effects of surgery and medical management with cornual puncture and injection of potassium chloride. Likewise, in these cases a thorough follow-up is obligatory.

References- Surbone A, Cottier O, Vial Y, Francini K, Hohlfeld P, Achtari C. Interstitial pregnancies’ diagnosis and management: an eleven cases series. Swiss Med Wkly. 2013;143:w13736. Published 2013 Feb 27. doi:10.4414/smw.2013.13736

- Larraín D., Marengo F., Bourdel N., et al. Proximal ectopic pregnancy: a descriptive general population–based study and results of different management options in 86 cases. Fertility and Sterility. 2011;95(3):867–871. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.10.025

- Jurkovic D, Wilkinson H. Diagnosis and management of ectopic pregnancy. BMJ 2011;342:d3397.

- Faraj R, Steel M. Management of cornual (interstitial) pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;9:249–255.

- Doubilet P, Benson CB. Atlas of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology: A Multimedia Reference. Philadelphia, PA: Lippin-cott, Williams & Wilkins, 2003.

- Moawad NS, Mahajan ST, Moniz MH, Taylor SE,Hurd WW. Current diagnosis and treatment of interstitialpregnancy.Am J Obstet Gynecol2010;202:15–29.

- Kalidindi M, et al., Expect the unexpected: The dilemmas in the diagnosis and management of interstitialectopic pregnancydCase report and literature review, Gynecology and Minimally Invasive Therapy (2015), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gmit.2015.09.006

- Malinowski A, Bates K. Semantics and pitfalls in the diagnosis of cornual/interstitial pregnancy.Fertil Steril. 2006;86:1764.e11-1764.e14

- Kalidindi, Madhavi & Shahid, Anupama & Odejinmi, Jimi. (2015). Expect the unexpected: The dilemmas in the diagnosis and management of interstitial ectopic pregnancy—Case report and literature review. Gynecology and Minimally Invasive Therapy. 5. 10.1016/j.gmit.2015.09.006

- Chan LYS, Fok WY, Yuen PM. Pitfalls in diagnosis of interstitial pregnancy.ActaObstet Gynaecol Scand. 2003;82:867-870.

- Faraj R, Steel M. Management of cornual (interstitial) pregnancy.ObstetGynaecol.2007;9:249-255.

- Tulandi T, Barbieri RL and Falk SJ. Ectopic pregnancy: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. UpToDate, 13 October 2015.

- Dendas W, Schobbens JC, Mestdagh G, Meylaerts L, Verswijvel G, Van Holsbeke C. Management and outcome of heterotopic interstitial pregnancy: Case report and review of literature. Ultrasound. 2017;25(3):134-142. doi:10.1177/1742271X17710965 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5794052

- Molinaro TA, Barnhart KT, Levine D, et al. Abdominal pregnancy, cesarean scar pregnancy, and heterotopic pregnancy. UpToDate, 26 October 2015.

- Sentilhes L, Bouet PE, Gromez A, et al. Successful expectant management for a cornual heterotopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril 2009; 91 934.e11–3.

- Habana A, Dokras A, Giraldo JL, et al. Cornual heterotopic pregnancy: Contemporary management options. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000; 182: 1264–1270.

- Chin HY, Chen FP, Wang CJ, et al. Heterotopic pregnancy after in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2004; 86: 411–416.

- Kirk E, Bottomley C, Bourne T. Diagnosing ectopic pregnancy and current concepts in the management of pregnancy of unknown location. Human Reproduction Update 2014;20(2):250‐61.

- Takeda A, Koyama K, Imoto S, Mori M, Sakai K, Nakamura H. Successful management of interstitial pregnancy with fetal cardiac activity by laparoscopic-assisted cornual resection with preoperative transcatheter uterine artery embolization. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009;280:305–308.

- Sagiv R, Debby A, Keidar R, Kerner R, Golan A. Interstitial pregnancy management and subsequent pregnancy outcome. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2013;92:1327–1330.

- Escobar-Padilla B, Perez-López CA, Martínez-Puon H. Risk factors and clinical features of ectopic pregnancy. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc 2017 May–Jun;55: 278–285.

- Rizk B, Holliday CP, Abuzeid M. Challenges in the diagnosis and management of interstitial and cornual ectopic pregnancies. Middle East Fertil Soc J 2013; 18: 235–240.

- Ngu SF, Cheung VY. Non‐tubal ectopic pregnancy. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 2011;115(3):295‐7.

- Molinaro TA, Barnhart KT. Ectopic pregnancies in unusual locations. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine 2007;25(2):123–30.

- Tulandi T, Al‐Jaroudi D. Interstitial pregnancy: results generated from The Society of Reproductive Surgeons Registry. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2004;103(1):47–50.

- Zhang X, Xinchang L, Fan H. Interstitial pregnancy and transcervical curettage. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2004;104(5):1193–5.

- Shen L, Fu J, Huang Wet al. Interventions for non-tubalectopic pregnancy.Cochrane Database Syst Rev2014; (7):CD011174. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD011174/full

- Zhang Q, Li Yp, Prasad DJ, et al. Treatment of cornual heterotopic pregnancy via selective reduction without feticide drug. J Minim Invasive Gynecol 2011; 18: 766–768.

- Chetty M, Elson J. Treating non‐tubal ectopic pregnancy. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 2009;23(4):529‐38.