What is inverse psoriasis

Inverse psoriasis also known as intertriginous psoriasis or flexural psoriasis, shows up as very red, smooth, and shiny lesions in body folds 1. Many people with inverse psoriasis have another type of psoriasis elsewhere on the body at the same time. Recent studies suggest that 3% to 12% of psoriatic patients manifest inverse psoriasis 2. Unfortunately, compared to other forms of psoriasis, inverse psoriasis is often not as easy to identify.

The lesions of inverse psoriasis are erythematous and sharply demarcated, as in plaque psoriasis, but scales are typically absent. The surface is smooth, moist, macerated, or all three and may contain fissures 3. Inverse psoriasis may be malodorous, pruritic, or both 4. If present, psoriasiform lesions elsewhere on the body, a family history of psoriasis, and characteristic nail abnormalities support a diagnosis of inverse psoriasis 5. The most common nail disorders observed in psoriatic patients include oil spots, pitting, subungual hypertrophy, and onycholysis 6.

Inverse psoriasis is easily mistaken for infectious dermatoses, particularly bacterial or fungal intertrigo 7. Intertrigo is inflammation of opposed skin folds caused by skin-on-skin friction that presents as erythematous, macerated plaques. Secondary bacterial and fungal infections are common because the moist, denuded skin provides an ideal environment for growth of microorganisms. Candida is the most common fungal organism associated with intertrigo 5. Intertiginous candidiasis presents as well-demarcated, erythematous patches with satellite papules or pustules at the periphery 7. The presence of peripheral satellite papules or pustules can help differentiate intertriginous candidiasis from inverse psoriasis. Potassium hydroxide examination of skin scrapings should be performed if Candida is suspected because pseudohyphae confirm the diagnosis of candidiasis 4. Two studies have demonstrated an absence of Candida in inverse psoriasis lesions 8.

Common sites of inverse psoriasis are 9:

- Armpits

- Groin

- Under the breasts

- Umbilicus (navel)

- Penis

- Vulva

- Natal cleft (between the buttocks)

- Around the anus

Many patients have psoriasis affecting other sites, particularly inside the ear canal, behind the ears, through the scalp, and on elbows and knees.

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated disease that causes raised, red, scaly patches to appear on the skin. Psoriasis typically affects the outside of the elbows, knees or scalp, though it can appear on any location. Some people report that psoriasis is itchy, burns and stings. Psoriasis is associated with other serious health conditions, such as diabetes, heart disease and depression.

If you develop a rash that doesn’t go away with an over-the-counter medication, you should consider contacting your doctor.

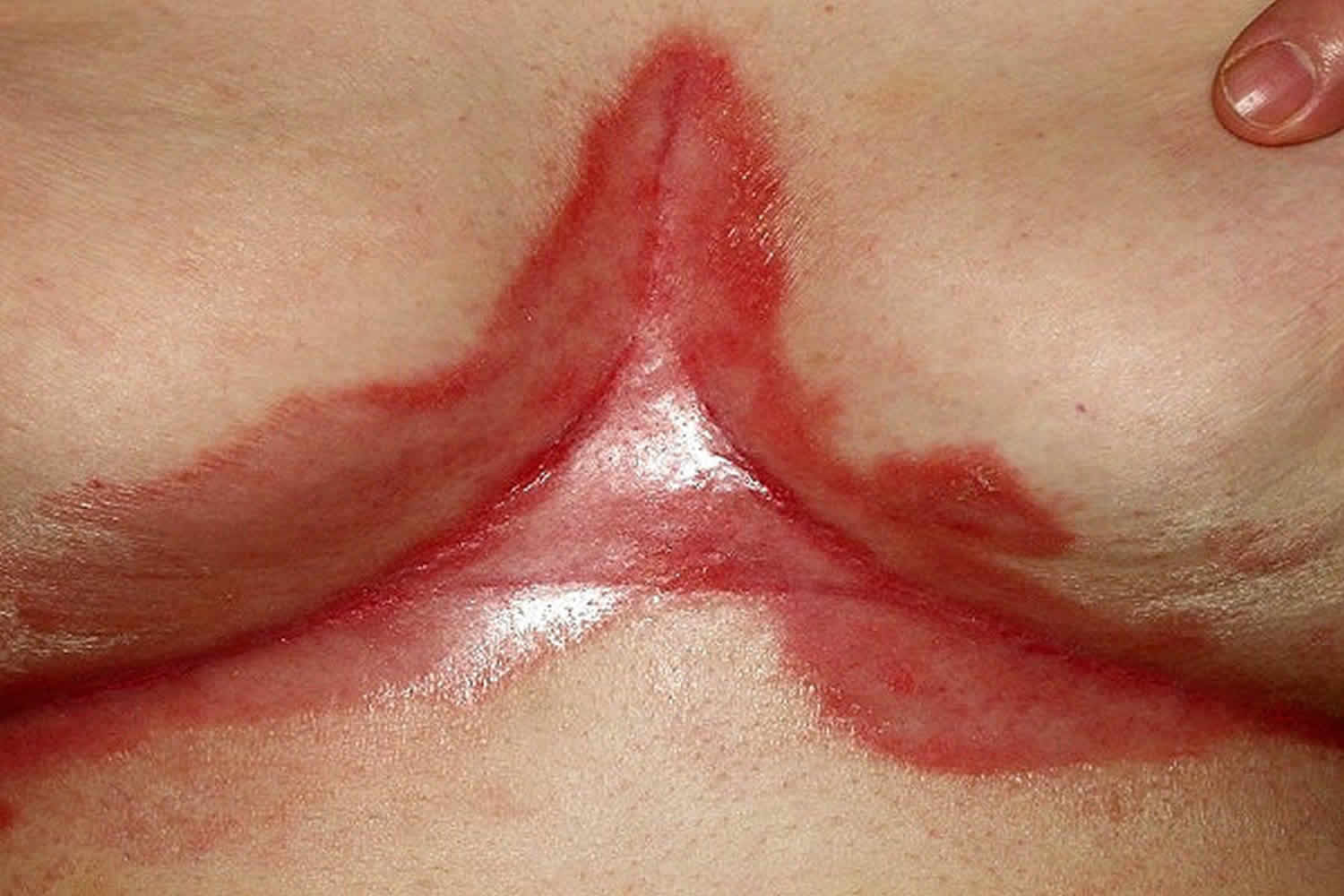

Figure 1. Inverse psoriasis groin

Footnote: A 68-year old woman with a history of poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus presented as a new patient with exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and a rash. The rash consisted of chronic, recurrent, erythematous patches in the inframammary and inguinal folds (Figure 1). The patches were mildly macerated. Scanty satellite lesions were observed near the inframammary but not the inguinal patches; scales were absent in these locations. There was scaling and tenderness in both auditory canals, with mild scaling of each pinna. Over the past week, the patient had applied multiple topical medications to the rash, including clotrimazole, moisturizer, and bacitracin/neomycin/polymyxin. She reported a 10-year history of similar rash affecting the axillae, groin, inframammary folds, retroauricular area, and gluteal cleft. The skin lesions had been diagnosed previously as candidiasis, but the patient was adamant that multiple trials with topical and oral antifungals did not help the rash. It is interesting that she noted that the skin lesions always improved when she was taking prednisone for the treatment of COPD exacerbations.

The patient was prescribed prednisone for her COPD exacerbation and neomycin-polymyxin B-hydrocortisone otic solution for presumed otitis externa. Antifungal cream was offered but the patient was certain it would not help and insisted the prednisone would resolve the rash. She was instructed to discontinue all topical products for the rash and to return for follow-up. She presented 1 week later with a dramatic improvement in her rash. However, within 2 weeks of terminating oral prednisone, the erythematous patches recurred in the inframammary folds and gluteal cleft. The differential diagnosis included intertrigo, erythrasma, seborrheic dermatitis, inverse psoriasis, and resistant Candida secondary to poorly controlled diabetes. The affected areas were examined with a Wood’s lamp and demonstrated no signs of fluorescence that would suggest erythrasma. A fungal culture was obtained, and clotrimazole-betamethasone dipropionate topical cream was prescribed to cover both fungal and psoriatic etiologies. Four weeks later, the fungal culture showed no growth and the rash had improved. The lack of growth on the fungal culture and resolution of the rash with oral and topical steroids suggested a diagnosis of inverse psoriasis. To avoid skin atrophy in intertriginous areas from prolonged steroid use, the patient was prescribed topical tacrolimus for exacerbations.

She had a good response to tacrolimus initially. When this response began to wane, she was referred to dermatology, where a diagnosis of inverse psoriasis was confirmed. A daily regimen of topical tacrolimus was initiated, with desonide ointment prescribed for flares. The rash was well controlled at follow-up 3 months later.

[Source 1 ]Figure 2. Inverse psoriasis armpit

Figure 3. Inverse psoriasis breast

Clinical features of inverse psoriasis

Due to the moist nature of the skin folds the appearance of the psoriasis is slightly different. It tends not to have silvery scale, but is shiny and smooth. There may be a crack (fissure) in the depth of the skin crease. The deep red colour and well-defined borders characteristic of psoriasis may still be obvious.

Scaly plaques may sometimes occur however, particularly on the circumcised penis.

inverse psoriasis can be difficult to tell apart from seborrheic dermatitis, or may co-exist. Seborrheic dermatitis in skin folds tends to present as thin salmon-pink patches that are less well defined than psoriasis. If there is any doubt which is responsible, or there is thought to be overlap of the two conditions, the term sebopsoriasis may be used.

Complications of inverse psoriasis include:

- Chaffing and irritation from heat and sweat

- Secondary fungal infections particularly Candida albicans (thrush)

- Lichenification (a type of eczema) from rubbing and scratching – this is a particular problem around the anus where faecal material irritates causing

- increased itching

- Sexual difficulties because of embarrassment and discomfort

- Thinned skin due to long term overuse of strong topical steroid creams

Inverse psoriasis trigger

Psoriasis triggers are not universal. What may cause one person’s psoriasis to become active, may not affect another. Established psoriasis triggers include:

Stress

Stress can cause psoriasis to flare for the first time or aggravate existing psoriasis. Relaxation and stress reduction may help prevent stress from impacting psoriasis.

Injury to skin

Psoriasis can appear in areas of the skin that have been injured or traumatized. This is called the Koebner phenomenon. Vaccinations, sunburns and scratches can all trigger a Koebner response. The Koebner phenomenon can be treated if it is caught early enough.

Medications

Certain medications are associated with triggering psoriasis, including:

- Lithium: Used to treat manic depression and other psychiatric disorders. Lithium aggravates psoriasis in about half of those with psoriasis who take it.

- Antimalarials: Plaquenil, Quinacrine, chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine may cause a flare of psoriasis, usually two to three weeks after the drug is taken. Hydroxychloroquine is the least likely to cause side effects.

- Inderal: This high blood pressure medication worsens psoriasis in about 25 percent to 30 percent of patients with psoriasis who take it. It is not known if all high blood pressure (beta blocker) medications worsen psoriasis, but they may have that potential.

- Quinidine: This heart medication has been reported to worsen some cases of psoriasis.

- Indomethacin: This is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug used to treat arthritis. It has worsened some cases of psoriasis. Other anti-inflammatories usually can be substituted. Indomethacin’s negative effects are usually minimal when it is taken properly. Its side effects are usually outweighed by its benefits in psoriatic arthritis.

Infection

Anything that can affect the immune system can affect psoriasis. In particular, streptococcus infection (strep throat) is associated with guttate psoriasis. Strep throat often is triggers the first onset of guttate psoriasis in children. You may experience a flare-up following an earache, bronchitis, tonsillitis or a respiratory infection, too.

It’s not unusual for someone to have an active psoriasis flare with no strep throat symptoms. Talk with your doctor about getting a strep throat test if your psoriasis flares.

Other possible triggers

Although scientifically unproven, some people with psoriasis suspect that allergies, diet and weather trigger their psoriasis.

Inverse psoriasis treatment

Inverse psoriasis responds quite well to topical treatment but often recurs. If inverse psoriasis is diagnosed, short-term treatment (2 to 4 weeks) should be initiated with low- to mid-potency topical steroids, such as betamethasone valerate. The frequency of application can be tapered and ultimately discontinued if the psoriasis improves. Frequent and long-term use of low-potency topical steroids in intertriginous areas can result in atrophy, striae, and telangiectasia. For continued therapy beyond 2 to 4 weeks, calcipotriene, pimecrolimus, or tacrolimus should be initiated, or the low-dose topical steroid can be used 1 or 2 times per week for maintenance therapy 10. More resistant cases, like the one described herein, may require combination therapy. Other therapeutic options include botulinum toxin 11 and efalizumab 12, although evidence of their effectiveness is limited to case reports.

Topical steroids

Weak topical steroids (often in combination with an antifungal agent to combat thrush) may clear inverse psoriasis but it will usually recur sometime after discontinuing treatment. Stronger topical steroids need to be used with care and only for a few days, thinly and very accurately applied to the psoriasis. If the psoriasis has cleared, stop the steroid cream. The steroid cream may be used again short-term when the condition recurs.

Overuse of topical steroids in the thin-skinned body folds may cause stretch marks, marked thinning of the skin and can result in long term aggravation of psoriasis (tachyphylaxis).

Vitamin D-like compounds

Calcipotriol cream is an effective and safe treatment for psoriasis in the flexures and should be applied twice daily. If it irritates, it can be applied once daily and hydrocortisone cream 12 hours later.

Topical calcineurin inhibitors

Topical calcineurin inhibitors Tacrolimus ointment and pimecrolimus cream may be effective and do not cause skin thinning.

Combinations of the treatments listed above may be used, together with emollients. Antiseptics and topical antifungal agents are often recommended as inverse psoriasis may be complicated by bacteria and yeasts, including Candida albicans and Malassezia.

Strong topical agents

Treatments that are tolerated in other sites are often too irritating to use in skin folds, e.g., dithranol, salicylic acid and coal tar. However, it may be possible to use them by diluting in emollients, or by applying them for short periods and washing off.

Systemic agents are rarely required for limited inverse psoriasis and phototherapy is relatively ineffective because the folds are hidden from light exposure.

Oral or injected medications

If you have severe psoriasis or it’s resistant to other types of treatment, your doctor may prescribe oral or injected drugs. This is known as systemic treatment. Because of severe side effects, some of these medications are used for only brief periods and may be alternated with other forms of treatment.

- Retinoids. Related to vitamin A, this group of drugs may help if you have severe psoriasis that doesn’t respond to other therapies. Side effects may include lip inflammation and hair loss. And because retinoids such as acitretin (Soriatane) can cause severe birth defects, women must avoid pregnancy for at least three years after taking the medication.

- Methotrexate. Taken orally, methotrexate (Rheumatrex) helps psoriasis by decreasing the production of skin cells and suppressing inflammation. It may also slow the progression of psoriatic arthritis in some people. Methotrexate is generally well-tolerated in low doses but may cause upset stomach, loss of appetite and fatigue. When used for long periods, it can cause a number of serious side effects, including severe liver damage and decreased production of red and white blood cells and platelets.

- Cyclosporine. Cyclosporine (Gengraf, Neoral) suppresses the immune system and is similar to methotrexate in effectiveness, but can only be taken short-term. Like other immunosuppressant drugs, cyclosporine increases your risk of infection and other health problems, including cancer. Cyclosporine also makes you more susceptible to kidney problems and high blood pressure — the risk increases with higher dosages and long-term therapy.

- Drugs that alter the immune system (biologics). Several of these drugs are approved for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis. They include etanercept (Enbrel), infliximab (Remicade), adalimumab (Humira), ustekinumab (Stelara), golimumab (Simponi), apremilast (Otezla), secukinumab (Cosentyx) and ixekizumab (Taltz). Most of these drugs are given by injection (apremilast is oral) and are usually used for people who have failed to respond to traditional therapy or who have associated psoriatic arthritis. Biologics must be used with caution because they have strong effects on the immune system and may permit life-threatening infections. In particular, people taking these treatments must be screened for tuberculosis.

- Other medications. Thioguanine (Tabloid) and hydroxyurea (Droxia, Hydrea) are medications that can be used when other drugs can’t be given.

Home remedies

Although self-help measures won’t cure psoriasis, they may help improve the appearance and feel of damaged skin. These measures may benefit you:

- Take daily baths. Bathing daily helps remove scales and calm inflamed skin. Add bath oil, colloidal oatmeal, Epsom salts or Dead Sea salts to the water and soak. Avoid hot water and harsh soaps, which can worsen symptoms; use lukewarm water and mild soaps that have added oils and fats. Soak about 10 minutes then gently pat dry skin.

- Use moisturizer. After bathing, apply a heavy, ointment-based moisturizer while your skin is still moist. For very dry skin, oils may be preferable — they have more staying power than creams or lotions do and are more effective at preventing water from evaporating from your skin. During cold, dry weather, you may need to apply a moisturizer several times a day.

- Expose your skin to small amounts of sunlight. A controlled amount of sunlight can improve psoriasis, but too much sun can trigger or worsen outbreaks and increase the risk of skin cancer. First ask your doctor about the best way to use natural sunlight to treat your skin. Log your time in the sun, and protect skin that isn’t affected by psoriasis with sunscreen.

- Avoid psoriasis triggers, if possible. Find out what triggers, if any, worsen your psoriasis and take steps to prevent or avoid them. Infections, injuries to your skin, stress, smoking and intense sun exposure can all worsen psoriasis.

- Avoid drinking alcohol. Alcohol consumption may decrease the effectiveness of some psoriasis treatments. If you have psoriasis, avoid alcohol. If you do drink, keep it moderate.

Inverse psoriasis diet

In this 2018 systematic review 13 of 55 studies and 4534 patients with psoriasis, the researchers identify the strongest evidence for dietary weight reduction with a hypocaloric diet in overweight and obese patients with psoriasis. Diets mentioned in the study varied from 1,400 calories a day to a meager 800 calories. The utility of gluten-free diet and supplementation with vitamin D varies by subpopulations of adults with psoriatic diseases, and evidence is low for the utility of specific foods, nutrients, and dietary patterns in reducing psoriatic disease activity. The conclusion from that study was adults with psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis can supplement their medical therapies with dietary interventions to reduce disease severity. The authors are quick to point out, however, that medical treatments still lead the way in tackling psoriasis, and evidence has shown that the primary role of diet is to help mitigate disease symptoms in some patients.

Calorie counting can help for some

The paper’s 13 strongest recommendation is to reduce caloric intake if you are overweight or obese.

The link between weight and symptom severity among psoriasis patients is well established. In part because of body fat’s pro-inflammatory role, overweight or obese individuals face a host of issues – ranging from more severe symptoms to reduced treatment response – when trying to manage their disease.

The review recommends using weight loss to help mitigate these factors through what is known as a hypocaloric diet. In this case, “hypocaloric” refers to weight loss driven solely by consuming a smaller number of calories, rather than by exercise, surgery or changing nutrient portions, such as carbohydrates.

Weight loss will undoubtedly help your heart, but it certainly also can help your psoriasis too 13.

Of all the non-medical interventions overweight or obese people can receive, researchers gave evidence for hypocaloric diets their highest grade. Data on how weight loss affects people with a healthy weight, though, remains lacking.

While the authors strongly recommend gluten-free diets for people who face both celiac disease and psoriasis, they do not recommend the diet for anyone who has not tested positive for markers for celiac or gluten sensitivity.

Based on the lack of quality evidence for other supplements, such as selenium, fish oil and vitamin B12, the paper does not currently recommend them for psoriasis patients.

While topical vitamin D has been established as an effective treatment for psoriasis, there is little high-quality evidence to support the role of orally taking vitamin D to improve psoriasis, and the authors don’t recommend using it for prevention or treatment in adults with normal levels of vitamin D. Among patients with psoriatic arthritis, the paper suggests patients try one month of supplementation in addition to regular treatment.

References- Resistant “Candidal Intertrigo”: Could Inverse Psoriasis Be the True Culprit? J Am Board Fam Med March 2013, 26 (2) 211-214; https://www.jabfm.org/content/jabfp/26/2/211.full.pdf

- Dubertret L, Mrowietz U, Ranki A, et al.; EUROPSO Patient Survey Group. European patient perspectives on the impact of psoriasis: the EUROPSO patient membership survey. Br J Dermatol 2006;155:729–36

- van de, Kerkhof PC, Murphy GM, Austad J, Ljungberg A, Cambazard F, Duvold LB. Psoriasis of the face and flexures. J Dermatolog Treat 2007;18:351–60

- Chen JF, Liu YC, Wang WM. Dermacase. Can you identify this condition? Inverse psoriasis. Can Fam Physician 2011;57:903–4

- Janniger CK, Schwartz RA, Szepietowski JC, Reich A. Intertrigo and common secondary skin infections. Am Fam Physician 2005;72:833–8

- Lisi P. Differential diagnosis of psoriasis. Reumatismo 2007; 59 (Suppl 1): 56– 60

- Wolff K, Johnson R eds. Fitzpatrick’s Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology. 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2009

- Leibovici V, Alkalay R, Hershko K, et al. Prevalence of Candida on the tongue and intertriginous areas of psoriatic and atopic dermatitis patients. Mycoses 2008;51:63–6

- Lisi P. Differential diagnosis of psoriasis. Reumatismo 2007; 59 (Suppl 1): 56– 60.

- Kalb RE, Bagel J, Korman NJ, et al. Treatment of intertriginous psoriasis: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009;60:120–4

- Saber M, Brassard D, Benohanian A. Inverse psoriasis and hyperhidrosis of the axillae responding to botulinum toxin type A. Arch Dermatol 2011;147:629–30

- George D, Rosen T. Treatment of inverse psoriasis with efalizumab. J Drugs Dermatol 2009; 8: 74–6

- Ford AR, Siegel M, Bagel J, et al. Dietary Recommendations for Adults With Psoriasis or Psoriatic Arthritis From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: A Systematic Review . JAMA Dermatol. 2018;154(8):934–950. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1412