Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is a heterogeneous group of conditions, which encompasses all forms of arthritis (joint inflammation) of unknown cause, lasting for at least 6 weeks, with onset before the age of 16 years 1. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is the most common type of arthritis in kids and teens. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis typically causes joint pain and inflammation in the hands, knees, ankles, elbows and/or wrists. But, it may affect other body parts too. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis used to be called juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA), but the name changed because it is not a kid version of the adult disease. The term “juvenile arthritis” is used to describe all the joint conditions that affects kids and teens, including juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is an autoimmune disorder, which means that the immune system malfunctions and attacks the body’s organs and tissues, in this case the joints.

Researchers have described seven types of juvenile idiopathic arthritis 2. The types are distinguished by their signs and symptoms, the number of joints affected, the results of laboratory tests, and the family history (see Table 1 below).

- Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis causes inflammation in one or more joints. A high daily fever that lasts at least 2 weeks either precedes or accompanies the arthritis. Individuals with systemic arthritis may also have a skin rash or enlargement of the lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy), liver (hepatomegaly), or spleen (splenomegaly).

- Oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis also known as oligoarthritis, is marked by the occurrence of arthritis in four or fewer joints in the first 6 months of the disease. It is divided into two subtypes depending on the course of disease. If the arthritis is confined to four or fewer joints after 6 months, then the condition is classified as persistent oligoarthritis. If more than four joints are affected after 6 months, this condition is classified as extended oligoarthritis. Individuals with oligoarthritis are at increased risk of developing inflammation of the eye (uveitis).

- Rheumatoid factor positive polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis also known as polyarthritis or rheumatoid factor positive, causes inflammation in five or more joints within the first 6 months of the disease. Individuals with this condition also have a positive blood test for proteins called rheumatoid factors. This type of arthritis closely resembles rheumatoid arthritis as seen in adults.

- Rheumatoid factor negative polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis also known as polyarthritis or rheumatoid factor negative, is also characterized by arthritis in five or more joints within the first 6 months of the disease. Individuals with this type, however, test negative for rheumatoid factor in the blood.

- Psoriatic juvenile idiopathic arthritis involves arthritis that usually occurs in combination with a skin disorder called psoriasis. Psoriasis is a condition characterized by patches of red, irritated skin that are often covered by flaky white scales. Some affected individuals develop psoriasis before arthritis while others first develop arthritis. Other features of psoriatic arthritis include abnormalities of the fingers and nails or eye problems.

- Enthesitis-related juvenile idiopathic arthritis is characterized by tenderness where the bone meets a tendon, ligament, or other connective tissue. The most commonly affected places are the hips, knees, and feet. This tenderness, known as enthesitis, accompanies the joint inflammation of arthritis. Enthesitis-related arthritis may also involve inflammation in parts of the body other than the joints.

- The last type of juvenile idiopathic arthritis is called undifferentiated arthritis. This classification is given to affected individuals who do not fit into any of the above types or who fulfill the criteria for more than one type of juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

The incidence of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in North America and Europe is estimated to be 4 to 16 in 10,000 children. One in 1,000, or approximately 294,000, children in the United States are affected. The most common type of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in the United States is oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, which accounts for about half of all cases. For reasons that are unclear, females seem to be affected with juvenile idiopathic arthritis somewhat more frequently than males. However, in enthesitis-related juvenile idiopathic arthritis males are affected more often than females. The incidence of juvenile idiopathic arthritis varies across different populations and ethnic groups.

Table 1. Categories of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

| International League of Associations for Rheumatology Category | Previous Nomenclature | International League of Associations for Rheumatology Definition | Exclusion* | Adult Equivalent |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis | Systemic-onset juvenile rheumatoid arthritis | Arthritis and fever (≥2 weeks, documented quotidian × 3+ days) | 1, 2, 3, 4 | Adult Still disease |

| Plus 1 or more: | ||||

| • Evanescent erythematous rash | ||||

| • Generalized lymphadenopathy | ||||

| • Hepatosplenomegaly | ||||

| • Serositis | ||||

| Polyarticular rheumatoid factor-negative | Arthritis ≥5 joints during the first 6 months of disease and rheumatoid factor-negative | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | ||

| Polyarticular rheumatoid factor-positive | Arthritis ≥5 joints during the first 6 months of disease and rheumatoid factor-positive × 2 at least 3 months apart | 1, 2, 3, 5 | Rheumatoid arthritis (RF-positive) | |

| Oligoarthritis | Pauciarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis | Arthritis ≤4 joints during the first 6 months of disease; 2 subtypes are identified: | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 | |

| • Persistent oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis affecting no more than 4 joints | ||||

| • Extended oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, affecting a total of >4 joints after the first 6 months of disease | ||||

| Enthesitis-related arthritis | Seronegative enthesitis and arthritis syndrome Spondyloarthropathy | Arthritis and enthesitis | 1, 4, 5 | Ankylosing spondylitis (if bilateral sacroiliitis) |

| or | ||||

| Arthritis or enthesitis | ||||

| Plus 2 of: | ||||

| • Sacroiliac joint tenderness or inflammatory lumbosacral pain | ||||

| • HLA-B27+ | ||||

| • Onset of arthritis in a male older than age 6 years | ||||

| • Acute anterior uveitis | ||||

| • History of ankylosing spondylitis, enthesitis-related arthritis, sacroiliitis with inflammatory bowel disease, reactive arthritis, or acute anterior uveitis in first-degree relative | ||||

| Psoriatic arthritis | Arthritis and psoriasis or Arthritis plus 2 of: | 2, 3, 4, 5 | Psoriatic arthritis | |

| • Dactylitis | ||||

| • Nail pitting or onycholysis | ||||

| • Psoriasis in a first-degree relative | ||||

| Undifferentiated arthritis | Arthritis that fulfills criteria for: | |||

| • No category | ||||

| or | ||||

| • Two or more categories |

Footnotes: * Exclusion definitions: 1. Psoriasis in patient or first-degree relative; 2. HLA-B27+ male older than age 6 years; 3. Ankylosing spondylitis, enthesitis-related arthritis, sacroiliitis with inflammatory bowel disease, Reiter syndrome, or acute anterior uveitis in a first-degree relative; 4. Rheumatoid factor-positive in 2 assessments 3 months apart; 5. Systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis in patient.

Abbreviation: HLA=human leukocyte antigen

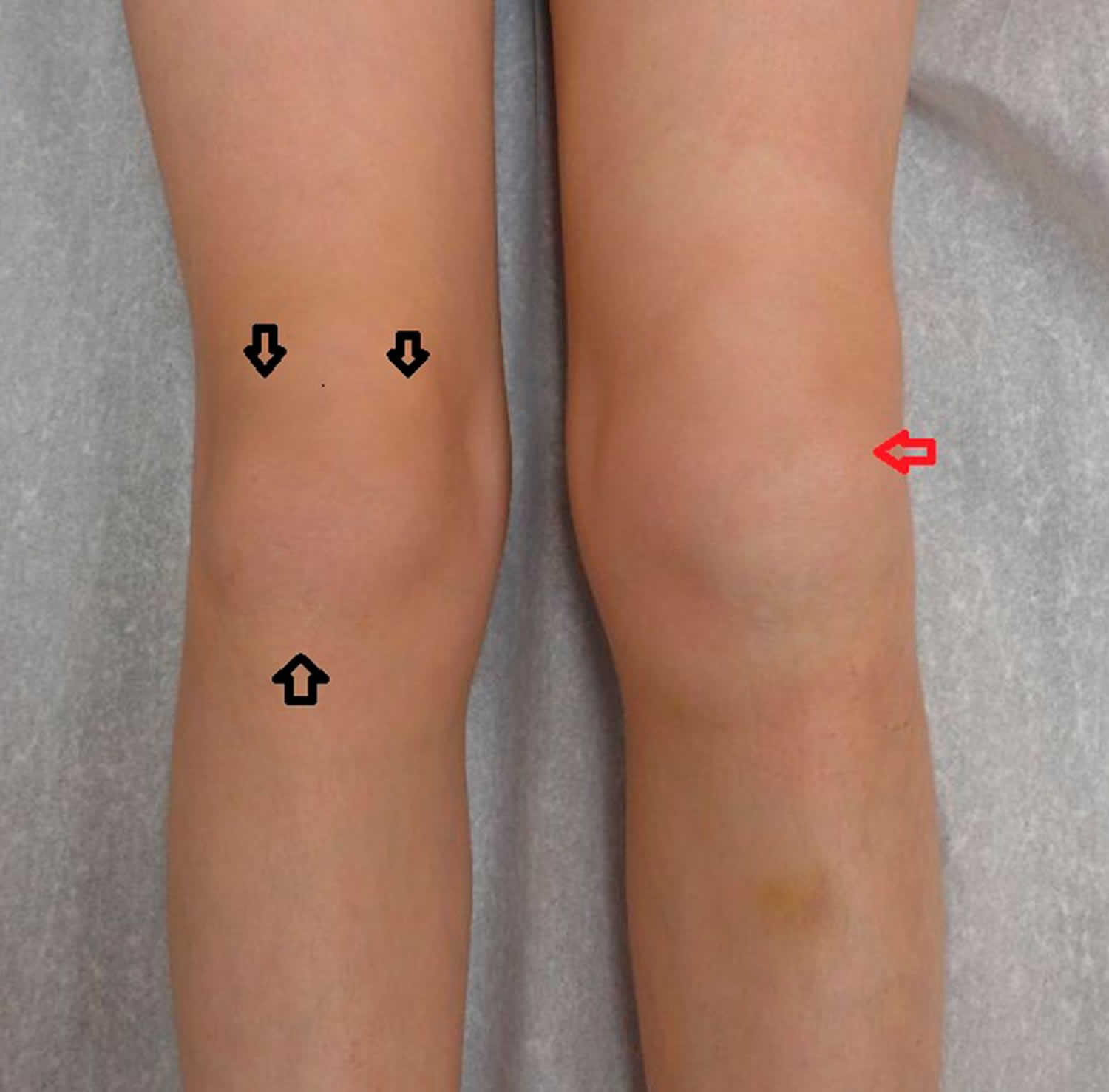

Figure 1. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Footnote: Knee in juvenile arthritis patient showing active arthritis of left knee (red arrow) and the positions for checking enthesitis (2, 6, and 10 o’clock, black arrows).

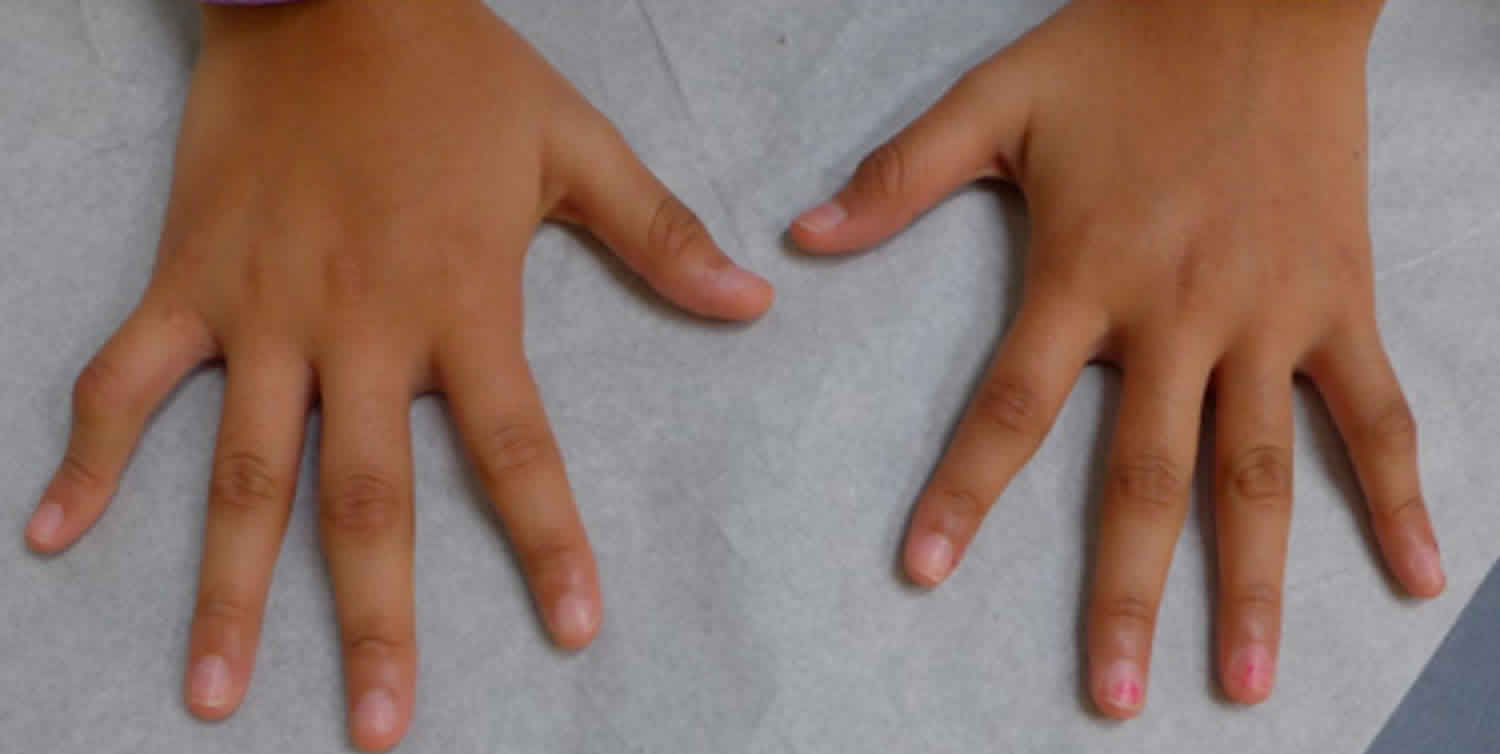

[Source 3 ]Figure 2. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

Footnote: Arthritis of several proximal interphalangeal joints bilaterally and flexion contractures with boutonniere deformity of bilateral fifth fingers in a child who has polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

[Source 3 ]Juvenile idiopathic arthritis causes

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is thought to arise from a combination of genetic and environmental factors. The term “idiopathic” indicates that the specific cause of the disorder is unknown and researchers aren’t sure why kids develop juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Scientists believe kids with juvenile idiopathic arthritis have certain genes that are activated by a virus, bacteria or other external factors. But there is no evidence that foods, toxins, allergies or lack of vitamins cause the disease.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is a type of autoimmune or autoinflammatory disease. That means the immune system, which is supposed to fight invaders like germs and viruses, gets confused and attacks the body’s cells and tissues. This causes the body to release inflammatory chemicals that attack the synovium (tissue lining around a joint). It produces fluid that cushions joints and helps them move smoothly. An inflamed synovium may make a joint feel painful or tender, look red or swollen or difficult to move.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis signs and symptoms result from excessive inflammation in and around the joints. Inflammation occurs when the immune system sends signaling molecules and white blood cells to a site of injury or disease to fight microbial invaders and facilitate tissue repair. Normally, the body stops the inflammatory response after healing is complete to prevent damage to its own cells and tissues. In people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis, the inflammatory response is prolonged, particularly during joint movement. The reasons for this excessive inflammatory response are unclear.

Researchers have identified changes in several genes that may influence the risk of developing juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Many of these genes are thought to play roles in immune system function. Some of these genes belong to a family of genes that provide instructions for making a group of related proteins called the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) complex. The HLA complex helps the immune system distinguish the body’s own proteins from proteins made by foreign invaders (such as viruses and bacteria). Each HLA gene has many different normal variations, allowing each person’s immune system to react to a wide range of foreign proteins. Certain normal variations of several HLA genes seem to affect the risk of developing juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and the specific type of the condition that a person may have.

Additional unknown genetic influences and environmental factors, such as infection and other issues that affect immune health, are also likely to influence a person’s chances of developing this complex disorder.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis inheritance pattern

Most cases of juvenile idiopathic arthritis are sporadic, which means they occur in people with no history of the disorder in their family. A small percentage of cases of juvenile idiopathic arthritis have been reported to run in families, although the inheritance pattern of the condition is unclear. A sibling of a person with juvenile idiopathic arthritis has an estimated risk of developing the condition that is about 12 times that of the general population.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis symptoms

It’s also possible that a child may start off with one type of juvenile idiopathic arthritis but develop symptoms of another type later.

The most common symptoms of juvenile idiopathic arthritis include:

- Joint pain or stiffness; may get worse after waking up or staying in one position too long.

- Red, swollen, tender or warm joints.

- Feeling very tired or rundown (fatigue).

- Blurry vision or dry, gritty eyes.

- Rash.

- Appetite loss.

- High fever.

Certain symptoms are specific to the type of arthritis a child has. There are six types of juvenile idiopathic arthritis:

- Oligoarthritis: Affects four or fewer joints, typically the large ones (knees, ankles, elbows). Most common subtype of juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

- Polyarthritis: Affects five or more joints, often on both sides of the body (both knees, both wrists, etc.). May affect large and small joints. Affects about 25% of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

- Systemic: Affects the entire body (joints, skin and internal organs). Symptoms may include a high spiking fever (103°F or higher) that lasts at least two weeks and rash. Affects about 10% of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

- Psoriatic arthritis (PsA): Joint symptoms and a scaly rash behind the ears and/or on the eyelids, elbows, knees, belly button and scalp. Skin symptoms may occur before or after joint symptoms appear. May affect one or more joints, often the wrists, knees, ankles, fingers or toes.

- Enthesitis-related: Also known as spondyloarthritis. Affects where the muscles, ligaments or tendons attach to the bone (entheses). Commonly affects the hips, knees and feet, but may also affect the fingers, elbows, pelvis, chest, digestive tract (Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis) and lower back (ankylosing spondylitis). More common in boys; typically appears in children between the ages of eight and 15.

- Undifferentiated: Symptoms don’t match up perfectly with any of the subtypes, but inflammation is present in one or more joints.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis symptoms may also come and go. Periods of lots inflammation and worsening symptoms are called flares. A flare can last for days or months.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis complications

If juvenile idiopathic arthritis inflammation goes unchecked, it can damage the lining that covers the ends of bones in a joint (cartilage), and the bones themselves. Here are some other ways juvenile idiopathic arthritis can affect the body:

- Eyes. Dryness, pain, redness, sensitivity to light and trouble seeing properly caused by uveitis (chronic eye inflammation). More common with oligoarthritis.

- Bones. Chronic inflammation and use of corticosteroids may cause growth delay in some children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Bones may get thinner and break more easily (osteoporosis).

- Mouth/Jaw. Difficulty chewing, brushing or flossing. More than half of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis have jaw involvement.

- Neck. Inflammation of the cervical spine can cause neck pain or stiffness. Swollen neck glands could also signal an infection for kids with Sjuvenile idiopathic arthritis or who take immunosuppressing drugs.

- Ankles/feet. Foot pain and difficulty walking. More common in polyarthritis and enthesitis-related arthritis.

- Skin. Symptoms can range from a faint salmon colored rash (Sjuvenile idiopathic arthritis) to a red, scaly rash (psoriatic arthritis).

- Lungs. Inflammation and scarring that can lead to shortness of breath and lung disease. May occur in Sjuvenile idiopathic arthritis.

- Heart. Inflammation may cause damage to the heart muscle. May occur in Sjuvenile idiopathic arthritis.

- Digestive Tract. Abdominal pain and diarrhea. More common in children with spine arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis.

- Reproductive organs. Late onset of puberty. Certain drugs such as cyclophosphamide may lead to fertility problems later.

- Weight loss or gain. Due to changes in appetite, jaw involvement or difficulty exercising. Being overweight puts extra stress on the joints.

Controlling inflammation and managing disease can prevent damage and complications from these health effects.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis diagnosis

According to American College of Rheumatology a child must have inflammation in one or more joints lasting at least six weeks, be under 16 years old and have all other conditions ruled out before being diagnosed with juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

A pediatrician may be the first doctor to start figuring out what’s causing symptoms. It’s likely that parents will be referred to a rheumatologist (a doctor with specialized training in treating arthritis). Some rheumatologists only treat children. Others only treat adults. Some of them treat both. A medical history, physical examination and blood tests helps to make the correct diagnosis.

Medical history. The doctor will ask questions about the child’s health history, when symptoms started and how long they lasted. This helps rule out other causes like trauma or infection. The doctor will also ask about the family’s medical history.

Physical examination. The doctor will look for joint tenderness, swelling, warmth and painful or limited movement and test range of motion. Eyes and skin may also be checked.

Laboratory tests. The doctor may order blood tests that look for certain proteins and chemicals found in some people with arthritis. These tests include:

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR, or “sed rate”) and C-reactive protein (CRP) tests: High ESR rates and CRP levels signal severe inflammation in the body.

- Antinuclear antibody (ANA) test: A positive ANA test is associated with many types of arthritis, but kids without juvenile idiopathic arthritis may also have a positive ANA.

- Rheumatoid factor (RF) test: May show up in children with polyarthritis. A positive rheumatoid factor may signal more serious disease.

- HLA-B27 typing (a genetic marker): The HLA-B27 gene is associated with enthesitis-related types of arthritis, such ankylosing spondylitis.

- Complete blood count (CBC): Raised levels of white blood cells and decreased levels of red blood cells is linked to certain types of arthritis.

- Imaging. The doctor may order imaging tests, such as X-rays, ultrasound and MRI or CT scans, to look for signs of joint damage.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis treatment

There is no cure for juvenile idiopathic arthritis but remission (little or no disease activity or symptoms) is possible. Early aggressive treatment is key to getting the disease under control as quickly as possible.

The goals of juvenile idiopathic arthritis treatment are to:

- Slow down or stop inflammation.

- Relieve symptoms, control pain and improve quality of life.

- Prevent joint and organ damage.

- Preserve joint function and mobility.

- Reduce long-term health effects.

- Achieve remission (little or no disease activity or symptoms).

Treatment for juvenile idiopathic arthritis varies depending on disease type and severity. A well-rounded plan includes medication, complementary therapies and healthy lifestyle habits.

Intra-articular steroid injections (triamcinolone hexacetonide or methylprednisolone acetate as the most used drugs), systemic steroids and methotrexate (MTX) have played a major role in the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis for many years. A recent trial has confirmed that the effectiveness of intra-articular steroid injections is not enhanced by concomitant administration of methotrexate 4. Nevertheless, juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients’ prognosis has dramatically changed in the last decades, thanks to the introduction of biologic agents at the beginning of 2000s. These medications have shown to be effective in a sizeable proportion of patients refractory or intolerant to methotrexate, although methotrexate remains the most widely used conventional treatment in the management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis for its effectiveness at achieving disease control, its acceptable toxic effects, worldwide availability and low cost 5. Among biologics, there are currently five anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) drugs available in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: four with published results [etanercept (ETN), adalimumab (ADA), infliximab (IFX) and golimumab], and one which has recently completed enrollment (certolizumab pegol) 6.

Table 2 shows the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Etanercept was the first TNF inhibitor to gain approval nearly two decades ago. The sustained efficacy and the good safety profile of etanercept have been confirmed in the open-label, multicentre CLIPPER study 7, by the national juvenile idiopathic arthritis German database BiKer 8, as well as in other multicentric studies, which showed a low rate of serious infections, just slightly increased compared with methotrexate alone 9.

Among TNF inhibitors, a recently approved treatment in polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis is golimumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody that can be administered by subcutaneous injection (a trial with intravenous infusion is on-going). Although the primary endpoint of the study was not met in the withdrawal phase (juvenile idiopathic arthritis flare rates with golimumab vs. placebo: 41 vs. 47%), golimumab caused a significant improvement in juvenile idiopathic arthritis and, therefore, has been approved by European Medicines Agency for the treatment of children with polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis and weight above 40 kg 6. Other alternatives to TNF inhibitors for treatment of polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis include tocilizumab and abatacept, both approved for use in polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis 10.

The IL-6 inhibitor tocilizumab (TCZ) and the IL-1 inhibitors (anakinra and canakinumab) are the most commonly prescribed biologic agents in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, whereas, rilonacept has not gone on to receive an approval for a juvenile idiopathic arthritis indication 11. The introduction of biologics in the treatment of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis has significantly increased the proportion of patients with inactive disease and reduced the occurrence of functional limitations because of the disease 12. Yokota et al.13 described more than 400 patients with sjuvenile idiopathic arthritis, all treated with tocilizumab and reported that, compared with previous studies, there were more serious adverse events, especially infections, but with an overall acceptable safety profile. Among 26 cases of macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), no deaths occurred, underling the importance of early detection and treatment of such a severe complication 14. Grom et al. 15. reported episodes of macrophage activation syndrome occurring in individuals with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis treated with canakinumab, but implicated infectious triggers rather than being caused by canakinumab.

Table 2. Interventional studies in juvenile idiopathic arthritis sponsored by pharmaceutical companies or investigator’s initiated studies

| Drug | Target | Dosage | Approval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abatacept | CD80/86 | 10 mg/kg week 0, 2, 4, then q4 weeks | EMA/FDA |

| Adalimumab | TNF-α | 24mg/m2 every 2 weeks; max 40mg | EMA/FDA |

| Anakinra | IL-1 | 1–4 mg/kg/day | EMA |

| Canakinumab | IL-1 | ≥2 years: 4 mg/kg/dose every 4 weeks Maximum dose: 300mg | EMA/FDA |

| Etanercept | TNF-α,β | 0.8 mg/kg/week or 0.4 mg/kg twice weekly; Maximum dose: 50mg | EMA/FDA |

| Infliximab | TNF-α | 6–10 mg/kg every 2 weeks to 2 months | – |

| Tocilizumab | IL-6 | polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis more than 2 years, less than 30 kg 10 mg/kg every 4 weeks polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis >2 years, more than 30 kg 8 mg/kg every 4 weeks systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis more than 2 years, less than 30 kg 12 mg/kg every 2 weeks more than 2 years, >30 kg 8 mg/kg every 2 weeks | EMA/FDA |

Abbreviations: EMA = European Medicines Agency; FDA = U.S. Food and Drug Administration

Medications

Drugs that control disease activity

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). These drugs work to modify the course of the disease. DMARDs relieve symptoms by suppressing the immune system so it doesn’t attack the joints.

- Traditional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). These have been used the longest and have a broad immune-suppressing effect. The most commonly-used drug for juvenile idiopathic arthritis is methotrexate. These medicines are available in pill or injection form.

- Biologics. These drugs target certain steps or chemicals in the inflammatory process and may work more quickly than traditional DMARDs. They are self-injected or given by infusion in a doctor’s office.

Drugs that relieve symptoms

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and analgesics (pain relievers). These drugs relieve pain but cannot reduce joint damage or change the course of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. These medications are available over-the-counter or by prescription.

Every child with juvenile idiopathic arthritis is different. The standard of care involves trying methotrexate first, but many doctors start with a biologic/disease-modifying antirheumatic drug (DMARD) combination to combat inflammation as quickly as possible. As doctors monitor the disease, drugs may be added or removed.

Exercise

Regular exercise helps ease joint stiffness and pain. Low-impact and joint-friendly activities like walking, swimming, biking and yoga are best, but kids with well-controlled disease can participate in just about any activity they wish, if their doctor or physical therapist approves.

Physical therapies and assistive devices

Physical and occupational therapy can improve a child’s quality of life by teaching them ways to stay active and how to perform daily tasks with ease. Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis may also have trouble with balance and weaker motor skills, or the ability to move and coordinate large muscle groups. Participating in regular physical and occupational therapy can improve coordination and balance, among other things. Here are some other ways physical and occupational therapists can help a child with juvenile idiopathic arthritis:

- Teach and guide them through strengthening and flexibility exercises.

- Perform body manipulation.

- Prescribe assistive devices (e.g. braces, splints).

Surgery

Thanks to treatment advances, including biologics, many children will never need surgery. But for children whose disease couldn’t be controlled early enough, surgery can provide much needed relief and restore joint function.

Damaged parts of a joint are replaced with metal, ceramic or plastic prosthesis. Hip and knee replacements are most common, and many surgeries can be performed on an outpatient basis. There are other surgeries that can improve joint function and quality of life but require much less cutting than joint replacement. For example, with arthroscopy, a thin, lighted tube with a camera attached is inserted through a small incision. This helps the surgeon examine the child’s joints and perform procedures, such as removing a loose piece of cartilage. An orthopedic surgeon will evaluate and determine if surgery is the best option.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Certain habits can help manage disease and relieve symptoms.

Healthy eating

While there is no special juvenile idiopathic arthritis diet, studies show that some foods help to curb inflammation. These include the foods found in the Mediterranean diet, i.e. fatty fish, fruits, vegetables, whole grains and extra virgin olive oil among others. Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis should avoid or cut back on foods that can cause inflammation such as high-fat, sugary and processed foods.

Balancing activity with rest

When juvenile idiopathic arthritis is active, and joints feel painful, swollen or stiff, it’s important to balance light activity with rest. Rest helps reduce inflammation and fatigue that can come with a flare. Taking breaks throughout the day protects joints and preserves energy.

Hot and cold treatments

Heat treatments, such as heat pads or warm baths, work best for soothing stiff joints and tired muscles. Cold is best for acute pain. It can numb painful areas and reduce inflammation.

Topical products

Creams, gels or stick-on patches can ease the pain in a joint or muscle. Some contain the same medicine that’s in a pill, and others use ingredients that irritate nerves to distract from pain.

Mind-Body Therapies

There are different ways to relax and stop focusing on pain. They include meditation, deep breathing and practicing visualization, or thinking about peaceful places or happy memories. Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis may also benefit from certain distraction techniques to lessen pain, especially during shot time. These include listening to music, coloring or drawing, reading and being read to.

Massage and acupuncture can also help reduce pain and ease stress or anxiety. Acupuncture involves inserting fine needles into the body along special points to relieve pain. If there’s a fear of needles, acupressure, which uses firm pressure, may be used instead.

Supplements

The use of supplements is rarely studied in children. But some supplements that adults take may help children too. These include curcumin, a substance found in turmeric, and omega-3 fish oil supplements, which may help with joint pain and stiffness. Taking calcium and vitamin D can help build strong bones. Always discuss supplements and vitamins with a child’s doctor. Some may cause side effects and interact with other medications.

Stress and emotions

Children and teens with juvenile idiopathic arthritis are more likely to get depressed because they are living with a chronic disease. Having a strong support system of friends and family can provide emotional support during tough times. Children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis can make new friends dealing with similar struggles at various Arthritis Foundation Juvenile Arthritis events held throughout the year. Therapist and psychologists can also help kids with juvenile arthritis deal with tough emotions and teach positive coping strategies.

Living with juvenile idiopathic arthritis

If you have juvenile idiopathic arthritis, it may be hard to get out of bed some mornings. Periods of inactivity, like sleeping for 8 hours, can be followed by stiffness.

It may be tempting to roll back into bed and sleep the day away, but that can make things worse. Even though you may feel lousy sometimes, gentle movement can help you feel better. Just as runners, bodybuilders, and other athletes do stretching exercises to warm up, gentle massaging and stretching can help soothe the muscles and ligaments around sore joints.

Once a person is up and moving, the discomfort usually lessens. Exercise can help keep full motion in your joints and strengthen your muscles and bones. A physical therapist can help you plan an effective exercise program to do at home.

Proper nutrition can improve anyone’s overall health. A dietitian can help you to understand the basics of a healthy diet. For example, when your symptoms flare up, you might feel sick and unable to eat as much. A dietitian can help you find foods that have a higher nutritional value to make up for having a poor appetite.

A positive mental outlook is just as important as exercise and a healthy diet. If you feel depressed or angry sometimes, talk to someone who can support you. Tell your parents, your doctor, or a friend about how you feel. It also may help to do simple things that we often take for granted. For example, each day try to do something that you enjoy and that makes you happy.

Most teens with juvenile idiopathic arthritis do the same stuff as other teens — go to regular schools, hang out with friends, and stay active physically, academically, and socially. Learning more about juvenile idiopathic arthritis and taking charge of your medical care can help some people feel more in control, too.

Your doctor and other medical professionals are there to support you and can help you manage the condition so that it has the least possible impact on your life.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis prognosis

In a study of 251 children from southern Sweden with a validated diagnosis of juvenile idiopathic arthritis 16, consisting of all subgroups in the total follow-up period, 40.0% of the years were with inactive disease (defined as no arthritis or uveitis), 54.8% were active due to arthritis with or without uveitis, and 5.2% were active because of uveitis only. The median follow-up time was 8.0 years. In the subgroups, the percentages of inactive disease presents as follows: enthesitis-related arthritis 38.4%, oligoarthritis 42.5% (with extended oligoarthritis 33.3% and persistent oligoarthritis 46.5%), rheumatoid factor-negative 37.3%, rheumatoid factor-positive 25.9%, juvenile psoriatic arthritis 33.3%, systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis 64.0%, and undifferentiated juvenile idiopathic arthritis 43.5%. 28.8% of the inactive years were without treatment. One patient that was lost to follow-up was later found out to have died.

Uveitis was seen in 27 (10.8%) of the children, 8.0% had chronic uveitis, and 4.0% had acute uveitis (3 individuals have had both manifestations). Fourteen of the children have had uveitis in their debut year (10 chronic). The median debut age of chronic uveitis is 5.5 years (range 0–16 years). There are no cases of uveitis in the rheumatoid factor-positive, juvenile psoriatic arthritis, or systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis groups. The risk of chronic uveitis is 10.0% at 12 years of follow-up.

In total, 23 (9.2%) individuals have been treated with joint corrective orthopedic surgery, 8 of them with multiple procedures (3 with rheumatoid factor-positive juvenile idiopathic arthritis, 2 with oligoarticular disease, 1 with rheumatoid factor-negative juvenile idiopathic arthritis, 1 with juvenile psoriatic arthritis and 1 with ujuvenile idiopathic arthritis). However, only 11 individuals (4.4%) have undergone large orthopedic surgery (arthroplasty, osteotomies, or arthrodesis). The procedures were 17 synovectomies (5 with diagnostic purpose), 7 arthrodeses, 6 osteotomies, 4 medial knee epiphysiodeses, 1 arthrolysis, 1 arthroplasty (hip prosthesis), 1 volar tenosynovectomy, and 1 finger tendon transposition. The need for orthopedic surgery is the highest (23.5%) in the group with rheumatoid factor-positive juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The risk for joint corrective surgery is 17.9% at 12 years of follow-up using. The risk for a serious orthopedic procedure is 9.4% at 12 years of follow-up.

References- Prakken B, Albani S, Martini A. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Lancet 2011; 377:2138–2149.

- Petty RE, Southwood TR, Manners P, Baum J, Glass DN, Goldenberg J, et al. International League of Associations for Rheumatology classification of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: second revision, Edmonton, 2001. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(2):390–2.

- Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis – Changing Times, Changing Terms, Changing Treatments. Pediatrics in Review May 2017, 38 (5) 221-232; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/pir.2016-0148

- Ravelli A, Davi S, Bracciolini G, et al. Italian Pediatric Rheumatology Study Group. Intra-articular corticosteroids versus intra-articular corticosteroids plus methotrexate in oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a multicentre, prospective, randomised, open-label trial. Lancet 2017; 389:909–916.

- Ruperto N, Murray KJ, Gerloni V, et al. Pediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization. A randomized trial of parenteral methotrexate comparing an intermediate dose with a higher dose in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis who failed to respond to standard doses of methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum 2004; 50:2191–2201.

- Brunner HI, Ruperto N, Tzaribachev N, et al. Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO) and the Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group (PRCSG)Subcutaneous golimumab for children with active polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results of a multicentre, double-blind, randomised-withdrawal trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2018; 77:21–29.

- Horneff G, Burgos-Vargas R, Constantin T, et al. Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (PRINTO)Efficacy and safety of open-label etanercept on extended oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis, enthesitis-related arthritis and psoriatic arthritis: part 1 (week 12) of the CLIPPER study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73:1114–1122.

- Becker I, Horneff G. Risk of serious infection in juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients associated with tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and disease activity in the German Biologics in Pediatric Rheumatology Registry. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2017; 69:552–560.

- Verazza S, Davi S, Consolaro A, et al. Italian Pediatric Rheumatology Study Group. Disease status, reasons for discontinuation and adverse events in 1038 Italian children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis treated with etanercept. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2016; 14:68.

- Brunner HI, Ruperto N, Zuber Z, et al. Efficacy and safety of tocilizumab in patients with polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis: results from a phase 3, randomised, double-blind withdrawal trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74:1110–1117.

- Ilowite NT, Prather K, Lokhnygina Y, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of the efficacy and safety of rilonacept in the treatment of systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014; 66:2570–2579.

- Horneff G, Schulz AC, Klotsche J, et al. Experience with etanercept, tocilizumab and interleukin-1 inhibitors in systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis patients from the BIKER registry. Arthritis Res Ther 2017; 19:256.

- Yokota S, Imagawa T, Mori M, et al. Longterm safety and effectiveness of the antiinterleukin 6 receptor monoclonal antibody tocilizumab in patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis in Japan. J Rheumatol 2014; 41:759–767.

- Yokota S, Itoh Y, Morio T, et al. Tocilizumab in systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a real-world clinical setting: results from 1 year of postmarketing surveillance follow-up of 417 patients in Japan. Ann Rheum Dis 2016; 75:1654–1660.

- Grom AA, Ilowite NT, Pascual V, et al. Rate and clinical presentation of macrophage activation syndrome in patients with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis treated with canakinumab. Arthritis Rheumatol 2016; 68:218–228.

- Outcome in Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. A Population-Based Study From Sweden. Arthritis Res Ther. 2019;21(218) https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/921281_5