What are knuckle pads

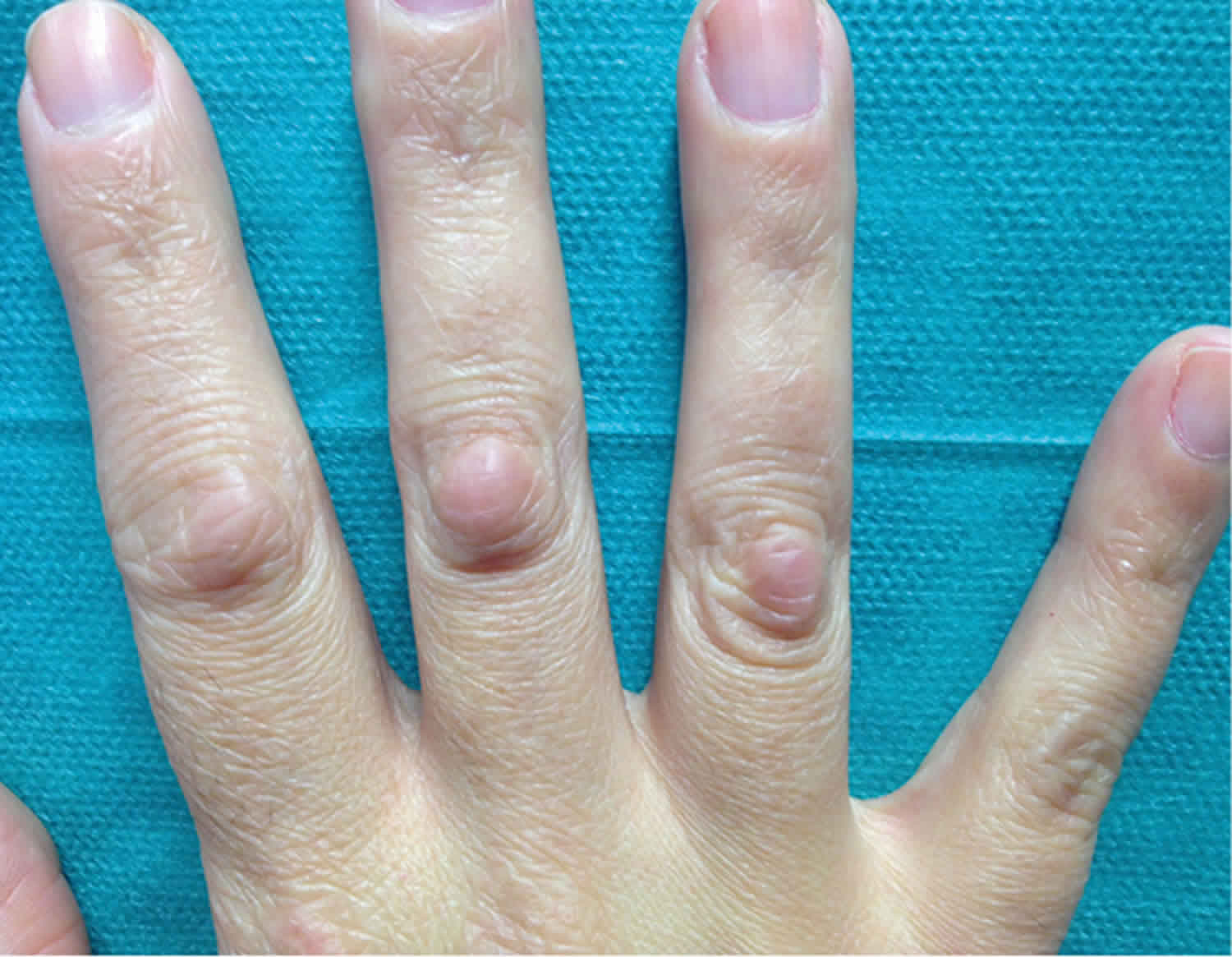

Knuckle pads also called Garrod pads, holoderma, keratosis supracapitularis, pulvinus and subcutaneous fibroma, are benign well-defined thickening, smooth, firm papules, nodules, or plaques over a finger joint. Knuckle pads are characterized by the progressive appearance of solitary or multiple thickened, callous-like, skin-coloured or slightly rosy papules and nodules overlying the metacarpophalangeal, distal interphalangeal and, more commonly, (PIP) joints 1. Knuckle pads typically are asymptomatic and overlie the joints on the dorsal hands; the thumbs and toes are less often involved. The name knuckle pad would seem to be a misnomer because in most reported cases, lesions occur over the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints rather than over the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joints, better known as the knuckles.

Hyperpigmented and hypopigmented knuckle pads have also been reported, especially among darker skin types 2. Knuckle pads may range from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter, and are often asymptomatic. Although available data on knuckle pads are scarce, it is often an inherited autosomal dominant trait that usually develops in teenage years and tends to persist throughout adulthood. In the largest epidemiological study to date, Paller et al 3 found that knuckle pads affected about 9% of almost 1900 people evaluated in Norway.

Knuckle pads are classified as a form of fibromatosis along with Dupuytren contracture (palmar fibromatosis), Ledderhose syndrome (plantar fibromatosis) and Peyronie disease (penile fibromatosis). Pseudo-knuckle pads are callus-like thickenings caused by repeated frictional trauma that have been linked to obsessive-compulsive behaviours in children (chewing pads), and occupational (eg carpet layers, tailors, live-chicken hangers, sheep shearers) or sporting activities in adults 4.

Most knuckle pads are asymptomatic and require no treatment. Neither medical nor surgical interventions for knuckle pads are very effective. Eliminating the source of mechanical or repetitive trauma may improve the lesions. Wearing protective gloves or changing occupation may be necessary. Intralesional injections of corticosteroids or fluorouracil may reduce the size of the lesions 5. Lesions caused by biting or sucking may require a psychiatrist to treat the underlying psychological problem. A cast or splint placed temporarily on the involved areas of the hand may aid in reducing the lesion. Application of silicone gel sheeting has had limited success 6. Applications of keratolytics, such as salicylic acid or urea, have helped to soften and even reduce the lesions. Radiation therapy and application of solid carbon dioxide have been reported to be of some help in selected cases. Complications of knuckle pads occur if surgery is used to remove the lesion. Complications include scar or keloid formation, recurrence, or tendon tethering.

What causes knuckle pads?

Although most cases of knuckle pads have an idiopathic origin, several dermatological and systemic disorders have been associated with knuckle pads 7. There is some debate as to whether true knuckle pads are a response to trauma (calluses). These are more likely to be callosities developing from repetitive pressure or friction, for example, occupational, sporting, finger sucking/chewing, or bulimia nervosa.

Some also attempt to distinguish ‘Dupuytren nodules’ and ‘dorsal cutaneous pads’, the former occurring only in patients with Dupuytren contracture and the latter occurring in both control and Dupuytren contracture populations.

Knuckle pads most commonly become apparent after the age of 30 years. Where there is a family history of knuckle pads, they usually appear at about the same age within a family. But the age of onset varies between families. In children, there is usually no apparent cause.

Knuckle pads can also develop as part of an inherited syndrome, may run in families together with other forms of fibromatosis, or as a sporadic occurrence.

Conditions associated with knuckle pads:

- Fibrosing conditions

- Peyronie´s disease

- Ledderhose disease

- Dupuytren´s contracture

- Fibromatosis

- Pachydermodactyly

- Genetic disorders

- Bart-Pumphrey syndrome

- Acrokeratoelastoidosis costa

- Keratoderma hereditaria mutilans

- Pseudoxanthoma elasticum

- Epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma

- Bart-Pumphrey syndrome

- Acrokeratoelastoidosis of Costa

- Camptodactyly

- Other

- Seborrheic dermatitis

- Clubbed fingers

- Oral leukoplakia

- Glossitis

- Avitaminosis A

- Oesophageal cancer

- Phenytoin treatment

The majority of knuckle-pad-related dermatoses are fibrosing conditions, including 8:

- Peyronie’s disease – thickening of the tunica albuginea

- Ledderhose disease – thickening of the plantar aponeurosis

- Dupuytren’s contracture – thickening of the palmar aponeurosis, which remains the strongest association.

An increased familial predisposition to knuckle pads has been observed in other fibromatosis and genetic disorders, including 9:

- pachydermodactyly – fibromatosis of the radial and ulnar regions of the proximal interphalangeal joints of the hand fingers

- Bart-Pumphrey syndrome – leukonychia, palmoplantar keratoderma and deafness

- acrokeratoelastoidosis costa

- keratoderma hereditaria mutilans

- pseudoxanthoma elasticum.

Less commonly, the following conditions have also been described in patients with knuckle pads 2:

- seborrheic dermatitis

- clubbed fingers (swelling of the soft tissues in the terminal phalanx of digits frequently seen in bronchopulmonary disease, cyanotic congenital heart disorders, cirrhosis and Crohn’s disease)

- oral leukoplakia

- glossitis

- avitaminosis A

- esophageal cancer

- phenytoin treatment.

Knuckle pads symptoms

A knuckle pad is more often located over a proximal interphalangeal (second) joint than over a knuckle (metacarpophalangeal/first joint) or distal interphalangeal (third) joint.

The pad may be seen over just one joint or many. The hands are most commonly affected but other joints, such as the feet and knees, may be involved.

Knuckle pads are well-defined, smooth, firm thickenings that can be flat or more obvious and dome-shaped. They generally do not cause any symptoms but can be tender or painful.

How are knuckle pads diagnosed?

Usually, knuckle pads are diagnosed clinically. However, there are several other conditions that may cause confusion including granuloma annulare, pachydermodactyly, rheumatoid nodules, and synovitis resulting in swollen joints. A skin biopsy may also be performed in cases of atypical presentations, and to differentiate them from other similar-looking dermatoses. Histological examination usually shows hyperkeratosis and acanthosis of the epidermis, along with a dense noncicatricial dermal proliferation of fibroblasts within loose bands of collagen 10. Spindle-shaped fibroblasts, seen by electron microscopy, are considered distinctive 2. Occasionally, musculoskeletal ultrasonography may be necessary to exclude underlying synovial proliferation 11. When associated with a keratin 9 gene mutation, as in epidermolytic palmoplantar keratoderma, suprabasal epidermolysis is also seen.

Ultrasound can be useful for distinguishing knuckle pads from synovitis.

Knuckle pads treatment

In general, treatment is not required for a knuckle pad because of the benign nature of the condition. Avoidance of repetitive behavior if possible may improve the situation. Moisturizers may be useful if the knuckle pads are hyperkeratotic. Keratolytics (e.g., salicylic acid topical or urea) cause cornified epithelium to swell, soften, macerate, and then desquamate. Surgical intervention may be indicated if knuckle pads cause a functional problem. Recurrence after surgery is likely, especially if the trauma that caused the initial knuckle pad is not eliminated. Scar or keloid formation may result from surgical intervention. Tendon tethering, another surgical complication, occurs only if the joint space or capsule is accidentally cut with damage to the tendon in the attempt to remove the knuckle pad 12.

References- Mackey SL, Cobb MW. Knuckle pads. Cutis 1994;54:159–60.

- Hyman CH, Cohen PR. Report of a family with idiopathic knuckle pads and review of idiopathic and disease-associated knuckle pads. Dermatol Online J 2013;19:18177

- Paller AS, Hebert AA. Knuckle pads in children. Am J Dis Child 1986;140:915–17

- Koba S, Misago N, Narisawa Y. Knuckle pads associated with clubbed fingers. J Dermatol 2007;34:838–40

- Weiss E, Amini S. A novel treatment for knuckle pads with intralesional Fluorouracil. Arch Dermatol. 2007 Nov. 143(11):1458-60.

- Quinn KJ. Silicone gel in scar treatment. Burns Incl Therm Inj. 1987 Oct. 13 Suppl:S33-40.

- Hyman CH, Cohen PR. Report of a family with idiopathic knuckle pads and review of idiopathic and disease-associated knuckle pads. Dermatol Online J 2013;19:18177.

- Dolmans GH, de Bock GH, Werker PM. Dupuytren diathesis and genetic risk. J Hand Surg Am 2012;37:2106–11

- Gönül M1, Gül Ü, Hizli P, Hizli Ö. A family of Bart-Pumphrey syndrome. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2012;78:178–78.

- Lagier R, Meinecke R. Pathology of ‘knuckle pads’. Study of four cases. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histol 1975;365:185–91

- Lopez-Ben R, Dehghanpisheh K, Chatham WW, Lee DH, Oakes J, Alarcón GS. Ultrasound appearance of knuckle pads. Skeletal Radiol 2006;35:823–27

- Addison A. Knuckle pads causing extensor tendon tethering. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1984 Jan. 66(1):128-30.