What is lithotomy position

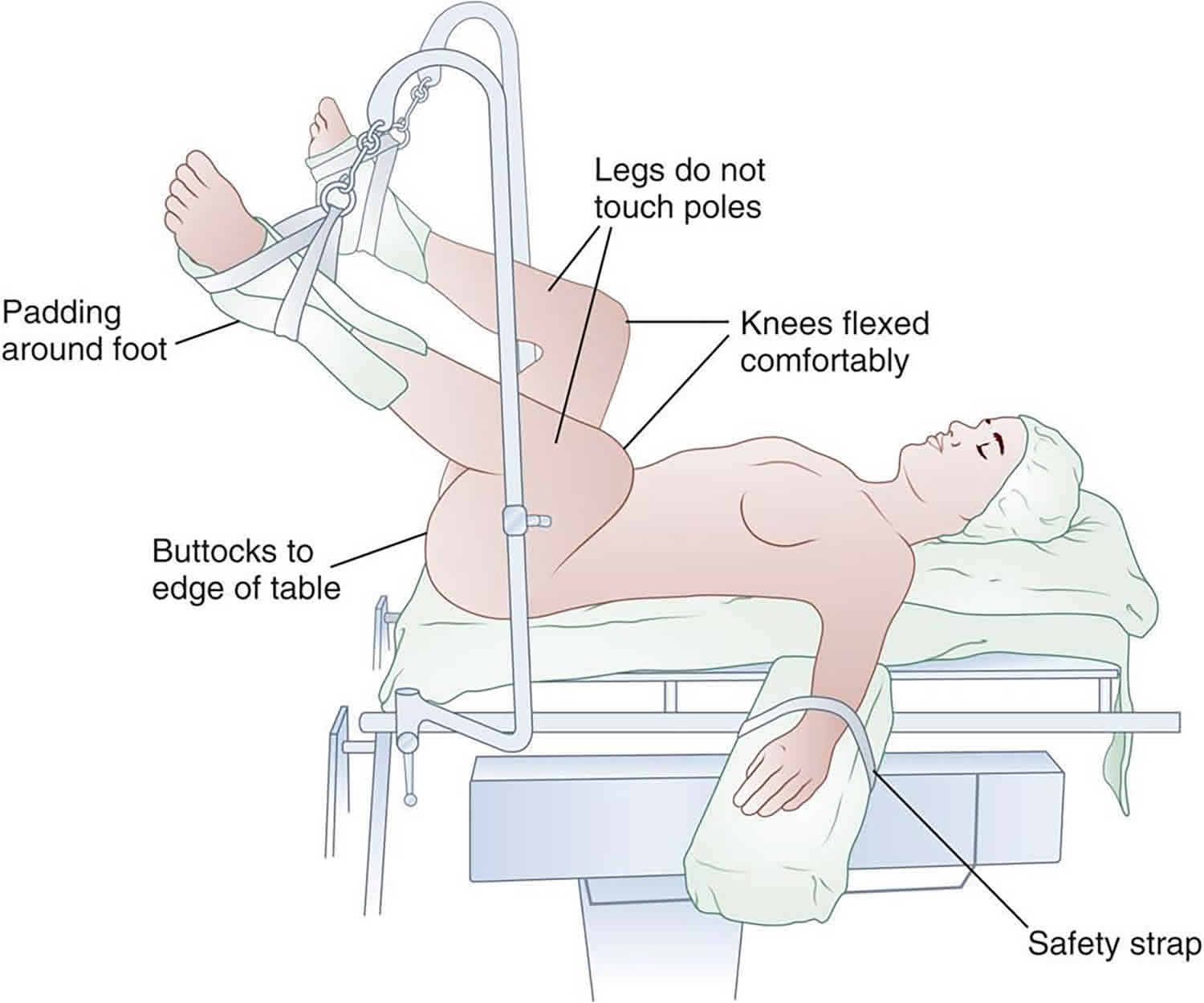

Lithotomy position is used in childbirth, gynecological examinations and gynecological, rectal, and urologic surgeries. Lithotomy position involves the woman lying on her back with her legs apart supported by stirrups so the knees and hips flexed anywhere from 80-100 degrees, the lower legs parallel to the body. The legs can be placed in straps, stirrups, or suspended in boots. And the legs can be in a low, high or exaggerated position. The higher the legs the greater the gradient for perfusion of the feet. There is a high risk of neurological and vascular complications.

The lithotomy position with the woman’s legs fixed in stirrups is used in many institutions both for spontaneous and particularly for assisted vaginal deliveries 1. The use of stirrups may be combined with lateral pelvic tilting and a semi‐recumbent posture with the mother sitting up at about 45 degrees, to reduce aortocaval compression.

When placing the legs in stirrups or taking them out of stirrups, both legs should be elevated and flexed at the hip simultaneously to prevent hip dislocation or postoperative back and hip pain.

Figure 1. Variations of lithotomy positions

Lithotomy position complications

- Acute compartmental syndrome: Lower extremity acute compartment syndrome is a pathologic condition in which increased tissue pressure within a closed osseofascial space compromises blood circulation and normal function of tissues within the compartment leading to tissue hypoxia and necrosis 2. If left untreated, patients with acute compartment syndrome can develop muscle contracture, sensory deficits, paralysis, possible need for limb amputation, and potentially multi-system organ failure secondary to crush syndrome 3. The osseofascial lining of the four lower extremity compartments (anterior, lateral, superficial and deep posterior) form an enclosed environment of muscle, blood vessels and nerves with limited ability to expand or accommodate increased volume or pressure 2. Acute compartment syndrome in the postoperative state occurs as a result of intraoperative compression with a prolonged decrease in arterial pressure and/or increase in venous pressure, followed by reperfusion 4. Local ischemia can subsequently damage endothelial cells resulting in leakage of proteins and fluid into the interstitial space. The subsequent increase in interstitial pressure elevates compartmental pressures, thus perpetuating the cycle of hypoperfusion and tissue ischemia 5. Specifically, in the lithotomy position, ischemia occurs from compressive forces of the external leg holsters and diminished blood flow from leg elevation and kinking of the popliteal artery, leading to ischemia/reperfusion injury with subsequent compartment syndrome 6. When the lower extremities are taken out of lithotomy position and elevation, limb reperfusion occurs and can lead to injury with the formation of oxygen free radicals and cytokines that perpetuate endothelial damage and interstitial edema 7. In addition to lithotomy position, other risk factors associated with acute compartment syndrome after surgery include: ankle dorsiflexion, Trendelenburg position, leg holders, length of surgery greater than 2 hours, intraoperative hypotension or hypovolemia, and epidural analgesia 6. Bauer and colleagues 8 recently published two articles documenting cases of lower extremity acute compartment syndrome following gynecologic surgery in the lithotomy position and found that the vast majority of acute compartment syndrome cases occurred following procedures lasting longer than 4 hour. Other studies have demonstrated that calf compartment pressure increases at a rate of 1.1 mmHg per hour in the lithotomy position 6. In addition, elevation of the leg above heart level (“high” lithotomy positon) has been associated with increased risk of compartment syndrome 9. Intermittent pneumatic compressive devices used for the prevention of deep venous thrombosis intraoperatively, as applied in the patient presented in this case report, have also been identified as causative factors for acute compartment syndrome 10. Multiple technical tricks have been described to prevent acute compartment syndrome in lithotomy position, including intraoperative repositioning of the legs, avoiding pressure in the popliteal fossa and kinking of the popliteal artery by avoiding knee flexion beyond 90° 11. Lower extremity acute compartment syndrome remains a clinical diagnosis, and immediate recognition and surgical management are paramount in avoiding long-term impairment and poor outcomes 12. The most common clinical symptom is represented by uncontrolled pain out of proportion and exacerbated pain by passive stretch of the toes and ankle joint 12. Measurement of the compartment pressure can aid in the diagnosis, albeit there is dispute among orthopedic surgeons regarding the pressure threshold for the diagnosis of acute compartment syndrome and subsequent need for fasciotomy. The most effective method of diagnosis of acute compartment syndrome remains a clinical diagnosis requiring a high level of suspicion by the treating physician.

- Ischemia, hypoxic edema, elevated tissue pressure, and rhabdomyolysis

- Compromise of the vascular structures in the popliteal space from leg holders supporting the leg under the knee

- Risk of brachial plexus injury if supination of hand with arm >90 degrees

- Possible finger injury when hands tucked with manipulation of the foot of the bed. Consider arms to side with padding if possible or wrap hands

- Obstruction of the popliteal vein and impedance of venous outflow due to extreme flexion of knee

- Neurapraxia (nerve injury)

Lithotomy position nerve injury

- Common peroneal nerve injury – most common nerve injury with lithotomy position (Foot drop, lower-extremity parasthesia)

- Femoral nerve or lumbosacral plexus stretch injuries caused by acute abduction and external rotation of the hips

- Arterial or venous occlusion and nerve injury from flexion of hips >90 degrees can cause kinking or compression of femoral neurovascular structures

Hyperflexion at the hip will render the patient susceptible to femoral nerve injury. The mechanism of injury relates to the fact that the rigid inguinal ligament compresses the femoral nerve trunk as the latter passes beneath it in its course from the abdomen into the thigh.

Hyperextension at the knee joint and hip can produce stretch injuries to the lumbosacral trunk and/or sciatic nerve. Short periods of leg extension with the feet in candy cane supports are tolerable, but after 30 minutes, the risk of injury is increased. Excessive abduction (>45°) over 2 hours will endanger the obturator, genital femoral, and/or femoral nerves. The latter nerve is particularly vulnerable when external rotation is added to abduction >45°. Compression at the head of the fibula will injure the peroneal division of the sciatic nerve, leading to paresis and pain in the leg following distribution of that nerve. Other causes of neuropathies associated with gynecologic surgery in patients who are not in the lithotomy position include self-retaining abdominal retractors, radical surgery, compression related to tight and prolonged packing, hematomas, tumors, and direct injury (e.g., incising the nerve). After draping, it is wise to change the position of the suspended inferior extremities when surgery extends beyond 2 hours. Additionally, relief of pressure from retractor blades should be carried out every hour or two. Care must be taken with assistants leaning or resting on a patient’s inferior extremities in the lithotomy position.

Preventive measures

Prevention of peroneal nerve damage

- Pad area of leg leaning against stirrups (or pad the stirrup), prevent hyperflexion of hip which can cause femoral and lateral femoral cutaneous nerve palsy, obturator and saphenous nerve injury may occur

Prevention of ulnar nerve injury

- Prevent with hands supinated and <90 degrees

- Symptoms are numbness/tingling in 4th and 5th finger, in severe cases a “claw-like” deformity

- Ulnar neuropathy more frequently associated with preexisting asymptomatic neuropathy, prolonged hospital stay, extremes of body habitus.

- Dundes L. The evolution of maternal birthing position. American Journal of Public Health 1987;77(5):636–41.

- von Keudell AG, Weaver MJ, Appleton PT, Bae DS, Dyer GS, Heng M, Jupiter JB, Vrahas MS. Diagnosis and treatment of acute extremity compartment syndrome. Lancet. 2015;386(10000):1299–310

- Genthon A, Wilcox SR. Crush syndrome: a case report and review of the literature. J Emerg Med. 2014;46(2):313–9

- Winston BA, VanSickle D, Winston KR. Resistance to venous flow: a mathematical description and implications for compartment syndromes. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2016 in press

- Hakaim AG, Cunningham L, White JL, Hoover K. Selective type III phosphodiesterase inhibition prevents elevated compartment pressure after ischemia/reperfusion injury. J Trauma. 1999;46(5):869–72

- Flierl MA, Stahel PF, Hak DJ, Morgan SJ, Smith WR. Traction table-related complications in orthopaedic surgery. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2010;18(11):668–75.

- Blaisdell FW. The pathophysiology of skeletal muscle ischemia and the reperfusion syndrome: a review. Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;10(6):620–30

- Bauer EC, Koch N, Erichsen CJ, Juettner T, Rein D, Janni W, Bender HG, Fleisch MC. Survey of compartment syndrome of the lower extremity after gynecological operations. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2014;399(3):343–8

- Tiwari A, Myint F, Hamilton G. Compartment syndrome. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2002;24(5):469

- Raza A, Byrne D, Townell N. Lower limb (well leg) compartment syndrome after urological pelvic surgery. J Urol. 2004;171(1):5–11

- Tomassetti C, Meuleman C, Vanacker B, D’Hooghe T. Lower limb compartment syndrome as a complication of laparoscopic laser surgery for severe endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(6):2038. e2039-2012

- Harvey EJ, Sanders DW, Shuler MS, Lawendy AR, Cole AL, Alqahtani SM, Schmidt AH. What’s new in acute compartment syndrome? J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26(12):699–702.