Lotus birth

Lotus Birth is the practice of not cutting the umbilical cord and leaving the placenta attached to the newborn after its expulsion, but allowed instead to dry and fall off on its own, which generally occurs 3–10 days after birth 1. Lotus birth may result in neonatal omphalitis 2 and cases of idiopathic neonatal hepatitis 3 following Lotus Birth have also been described in the literature.

The term “Lotus Birth” was coined in 1979 4 to identify the practice of not cutting the umbilical cord and of leaving the placenta attached to the newborn after its expulsion until it detaches spontaneously, which generally occurs 3–10 days after birth. According to the “Lotus Birth” advocates, the fetus and the placenta are formed from the same cells, and are therefore a single unit. Thus, if the newborn is not artificially separated from this part of itself, it will be endowed with a more robust immune system, as all the “vital force” contained in the placenta and a considerable amount of blood will be conveyed to it through the umbilical cord. Even babies delivered by means of cesarean section are said to benefit. Moreover, supporters of this method claim that, if the mother has suffered emotional trauma or stress during pregnancy, the baby will not display signs of “residual stress”; indeed, babies born in this way are described as “calm and well-balanced”: in short, “born with… the placenta”.

From the practical standpoint, this technique requires the mother to take her newborn baby home and to procure a sieve of appropriate size, which will be placed in a bowl and in which the placenta will be kept. The placenta will be preserved in this way for a minimum of two days up to a maximum of two weeks, during which time it will be treated with sea salt and ginger in order to improve its conservation and at the same time, reduce the unpleasant smell that a decomposing organ inevitably produces.

The first reported cases of Lotus Birth date back to 2004 in Australia 1. In Italy, it is estimated that about 100 women per year request this so-called “integral birth” 5.

Supporters of keeping the placenta attached after birth claim that the newborn is better perfused, endowed with a more robust immune system and “less stressed”.

However, it should be pointed out that histopathological study of the placenta is increasingly being requested in order to investigate problems of an infective nature or dysmaturity affecting the foetus, and situations of risk affecting the mother. Moreover, from the legal standpoint, there is no uniform position on the question of whether the placenta belongs to the mother or to the newborn. Lastly, a proper conservation of the embryonic adnexa is very difficult and includes problems of a hygiene/health, infectivological and medico-legal nature.

What is delayed umbilical cord clamping?

Delayed umbilical cord clamping is usually defined as umbilical cord clamping at least 30–60 seconds after birth 6. Before the mid 1950s, the term early clamping was defined as umbilical cord clamping within 1 minute of birth and late clamping was defined as umbilical cord clamping more than 5 minutes after birth. In a series of small studies of blood volume changes after birth, it was reported that 80–100 mL of blood transfers from the placenta to the newborn in the first 3 minutes after birth 7 and up to 90% of that blood volume transfer was achieved within the first few breaths in healthy term infants 8. Because of these early observations and the lack of specific recommendations regarding optimal timing, the interval between birth and umbilical cord clamping began to be shortened and it became common practice to clamp the umbilical cord shortly after birth, usually within 15–20 seconds. However, more recent randomized controlled trials of term and preterm infants as well as physiologic studies of blood volume, oxygenation, and arterial pressure have evaluated the effects of immediate versus delayed umbilical cord clamping usually defined as cord clamping at least 30–60 seconds after birth 6.

Process and technique of delayed umbilical cord clamping

Delayed umbilical cord clamping is a straightforward process that allows placental transfusion of warm, oxygenated blood to flow passively into the newborn. The position of the newborn during delayed umbilical cord clamping generally has been at or below the level of the placenta, based on the assumption that gravity facilitates the placental transfusion 9. However, a recent trial of healthy term infants born vaginally found that those newborns placed on the maternal abdomen or chest did not have a lower volume of transfusion compared with infants held at the level of the introitus 10. This suggests that immediate skin-to-skin care is appropriate while awaiting umbilical cord clamping. In the case of cesarean delivery, the newborn can be placed on the maternal abdomen or legs or held by the surgeon or assistant at close to the level of the placenta until the umbilical cord is clamped.

During delayed umbilical cord clamping, early care of the newborn should be initiated, including drying and stimulating for first breath or cry, and maintaining normal temperature with skin-to-skin contact and covering the infant with dry linen. Secretions should be cleared only if they are copious or appear to be obstructing the airway. If meconium is present and the baby is vigorous at birth, plans for delayed umbilical cord clamping can continue. The Apgar timer may be useful to monitor elapsed time and facilitate an interval of at least 30–60 seconds between birth and cord clamp.

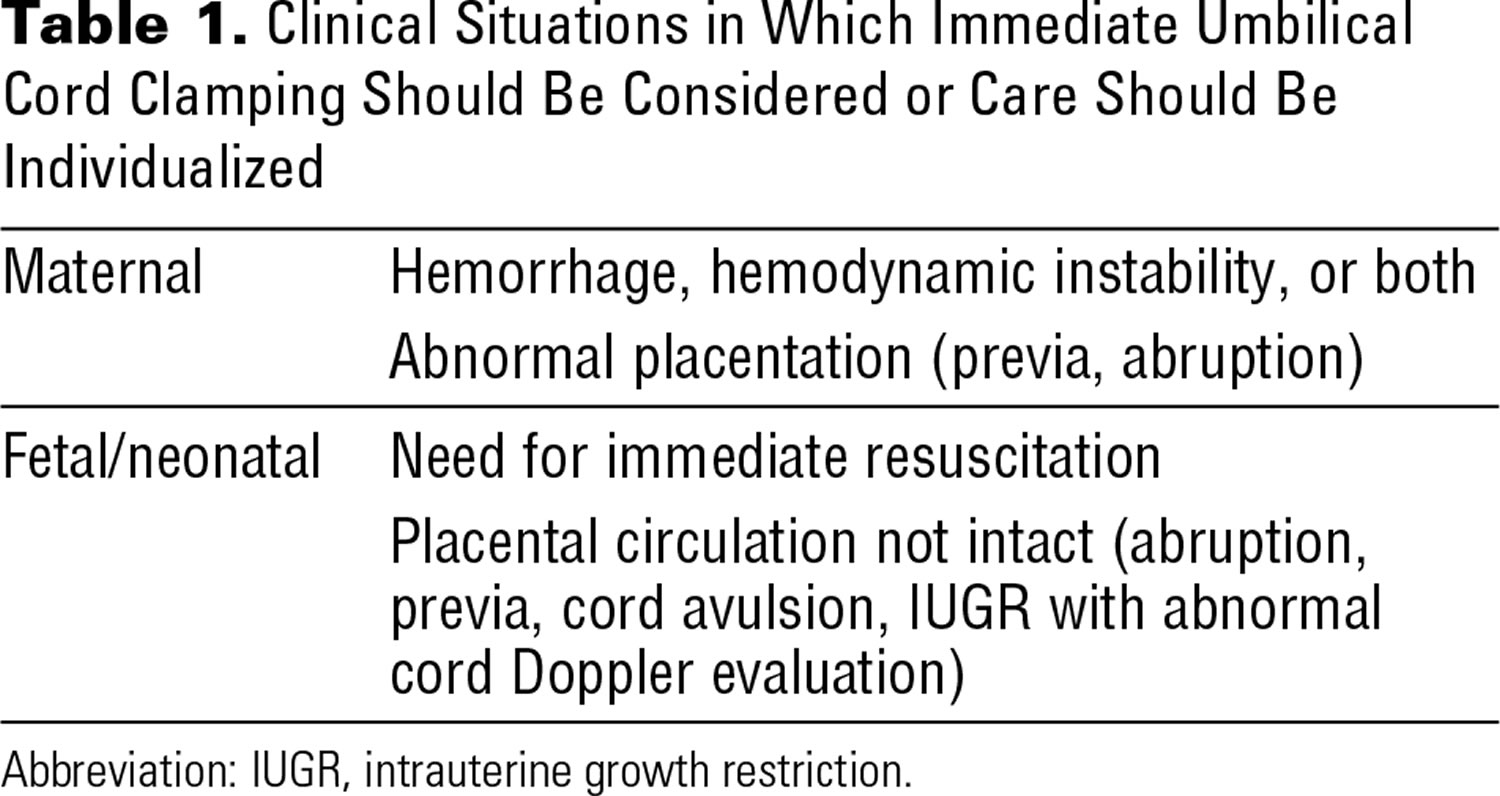

Delayed umbilical cord clamping should not interfere with active management of the third stage of labor, including the use of uterotonic agents after delivery of the newborn to minimize maternal bleeding. If the placental circulation is not intact, such as in the case of abnormal placentation, placental abruption, or umbilical cord avulsion, immediate cord clamping is appropriate. Similarly, maternal hemodynamic instability or the need for immediate resuscitation of the newborn on the warmer would be an indication for immediate umbilical cord clamping (Table 1). Communication with the neonatal care provider is essential.

The ability to provide delayed umbilical cord clamping may vary among institutions and settings; decisions in those circumstances are best made by the team caring for the mother–infant dyad. There are several situations in which data are limited and decisions regarding timing of umbilical cord clamping should be individualized (Table 1). For example, in cases of fetal growth restriction with abnormal umbilical artery Doppler studies or other situations in which uteroplacental perfusion or umbilical cord flow may be compromised, a discussion between neonatal and obstetric teams can help weigh the relative risks and benefits of immediate or delayed umbilical cord clamping.

Data are somewhat conflicting regarding the effect of delayed umbilical cord clamping on umbilical cord pH measurements. Two studies suggest a small but statistically significant decrease in umbilical artery pH (decrease of approximately 0.03 with delayed umbilical cord clamping) 11. However, a larger study of 116 infants found no difference in umbilical cord pH levels and found an increase in umbilical artery pO2 levels in infants with delayed umbilical cord clamping 12. These studies included infants who did not require resuscitation at birth. Whether the effect of delayed umbilical cord clamping on cord pH in nonvigorous infants would be similar is an important question requiring further study.

Clinical trials in preterm infants

A 2012 systematic review on timing of umbilical cord clamping in preterm infants analyzed the results from 15 eligible studies that involved 738 infants born between 24 weeks and 36 weeks of gestation 4. This review defined delayed umbilical cord clamping as a delay of more than 30 seconds, with a maximum of 180 seconds, and included some studies that also used umbilical cord milking in addition to delayed cord clamping. Delayed umbilical cord clamping was associated with fewer infants requiring transfusion for anemia (seven trials, 392 infants; relative risk [RR], 0.61; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.46–0.81). There was a lower incidence of intraventricular hemorrhage (ultrasonographic diagnosis, all grades) (10 trials, 539 infants; RR, 0.59;95% CI, 0.41–0.85) as well as necrotizing enterocolitis (five trials, 241 infants; RR, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.43–0.90) compared with immediate umbilical cord clamping. Peak bilirubin levels were higher in infants in the delayed umbilical cord clamping group, but there was no statistically significant difference in the need for phototherapy between the groups. For outcomes of infant death, severe (grade 3–4) intraventricular hemorrhage, and periventricular leukomalacia, no clear differences were identified between groups; however, many trials were affected by incomplete reporting and wide confidence intervals.

Outcome after discharge from the hospital was reported in a small study in which no significant differences were reported between the groups in mean Bayley II scores at age 7 months (corrected for gestational age at birth and involved 58 children) 4. In another study, delayed umbilical cord clamping among infants born before 32 weeks of gestation was associated with improved motor function at 18–22 months corrected age 17.

Clinical trials in term infants

A 2013 Cochrane review 6 assessed the effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping on term neonatal outcomes in 15 clinical trials that involved 3,911 women and their singleton infants. This analysis defined early umbilical cord clamping as clamping at less than 1 minute after birth and late umbilical cord clamping as clamping at more than 1 minute or when cord pulsation ceased. The reviewers found that newborns in the early umbilical cord clamping group had significantly lower hemoglobin concentrations at birth (weighted mean difference, –2.17 g/dL) as well as at 24–48 hours after birth (mean difference –1.49 g/dL). In addition, at 3–6 months of age, infants exposed to early umbilical cord clamping were more likely to have iron deficiency compared with the late cord clamping group.

There was no difference in the rate of polycythemia between the two groups, nor were overall rates of jaundice different, but jaundice requiring phototherapy was less common among those newborns who had early umbilical cord clamping (2.74% of infants in the early cord clamping group compared with 4.36% in the late cord clamping group). However, the authors concluded that given the benefit of delayed umbilical cord clamping in term infants, delayed cord clamping is beneficial overall, provided that the obstetrician–gynecologist or other obstetric care provider has the ability to monitor and treat jaundice.

Long-term effects of delayed umbilical cord clamping have been evaluated in a limited number of studies. In a single cohort, assessed from 4 months to 4 years of age 13, scores of neurodevelopment did not differ by timing of umbilical cord clamping among patients at 4 months and 12 months of age. At 4 years of age, children in the early umbilical cord clamping group had modestly lower scores in social and fine motor domains compared with the delayed umbilical cord clamping group 13.

Multiple gestations

Many of the clinical trials that evaluated delayed umbilical cord clamping did not include multiple gestations; consequently, there is little information with regard to its safety or efficacy in this group. Because multiple gestations increase the risk of preterm birth with inherent risks to the newborn, these neonates could derive particular benefit from delayed umbilical cord clamping. Theoretical risks exist for unfavorable hemodynamic changes during delayed umbilical cord clamping, especially in monochorionic multiple gestations. At this time, there is not sufficient evidence to recommend for or against delayed umbilical cord clamping in multiple gestations.

What is umbilical cord milking?

Umbilical cord milking or stripping has been considered as a method of achieving increased placental transfusion to the newborn in a rapid time frame, usually less than 10–15 seconds. It has particular appeal for circumstances in which the 30–60-second delay in umbilical cord clamping may be too long, such as when immediate infant resuscitation is needed or maternal hemodynamic instability occurs. However, umbilical cord milking has not been studied as rigorously as delayed umbilical cord clamping. A recent meta-analysis 14 of seven studies that involved 501 preterm infants compared umbilical cord milking with immediate cord clamping (six studies) or with delayed umbilical cord clamping (one study). The method of umbilical cord milking varied considerably in the trials in terms of the number of times the cord was milked, the length of milked cord, and whether the cord was clamped before or after milking. The analysis found that infants in the umbilical cord-milking groups had higher hemoglobin levels and decreased incidence of intraventricular hemorrhage with no increase in adverse effects. Subgroup analysis comparing umbilical cord milking directly with delayed umbilical cord clamping was not able to be carried out because of small numbers in those groups. Several subsequent studies have been published. A recent trial in term infants comparing delayed umbilical cord clamping with umbilical cord milking found that the two strategies had similar effects on hemoglobin and ferritin levels 15. Another recent trial evaluating infants born before 32 weeks of gestation found that among those infants born by cesarean delivery, umbilical cord milking was associated with higher hemoglobin levels and improved blood pressure compared with those in the delayed umbilical cord clamping group, but the differences were not seen among those born vaginally 16. Long-term (at age 2 years and 3.5 years) neurodevelopmental outcomes evaluated in one small study showed no difference between preterm infants exposed to delayed umbilical cord clamping compared with umbilical cord milking 17. This is an area of active research, and several ongoing studies are evaluating the possible benefits and risks of umbilical cord milking compared with delayed umbilical cord clamping, especially in extremely preterm infants. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to either support or refute umbilical cord milking in term or preterm infants.

Lotus birth benefits

At the present moment in time there is a lack of research regarding the safety and benefits of “Lotus Birth”. However, there are studies looking at the benefits of “delayed umbilical cord clamping” which is defined as umbilical cord clamping at least 30–60 seconds after birth 6 found delayed umbilical cord clamping appears to be beneficial for term and preterm infants. In term infants, delayed umbilical cord clamping increases hemoglobin levels at birth and improves iron stores in the first several months of life, which may have a favorable effect on developmental outcomes 18. However, there is a small increase in jaundice that requires phototherapy in this group of infants. Consequently, health care providers adopting delayed umbilical cord clamping in term infants should ensure that mechanisms are in place to monitor for and treat neonatal jaundice. In preterm infants, delayed umbilical cord clamping is associated with significant neonatal benefits, including improved transitional circulation, better establishment of red blood cell volume, decreased need for blood transfusion, and lower incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis and intraventricular hemorrhage. Delayed umbilical cord clamping was not associated with an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage or increased blood loss at delivery, nor was it associated with a difference in postpartum hemoglobin levels or the need for blood transfusion.

This growing body of evidence has led a number of professional organizations to recommend “delayed umbilical cord clamping” in term and preterm infants. For example, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that the umbilical cord not be clamped earlier than 1 minute after birth in term or preterm infants who do not require positive pressure ventilation 19. Recent Neonatal Resuscitation Program guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend delayed umbilical cord clamping for at least 30–60 seconds for most vigorous term and preterm infants. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) now recommends a delay in umbilical cord clamping in vigorous term and preterm infants for at least 30–60 seconds after birth. The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) also recommends deferring umbilical cord clamping for healthy term and preterm infants for at least 2 minutes after birth. Additionally, the American College of Nurse–Midwives recommends delayed umbilical cord clamping for term and preterm infants for 2–5 minutes after birth 20. The universal implementation of delayed umbilical cord clamping has raised concern. Delay in umbilical cord clamping may delay timely resuscitation efforts, if needed, especially in preterm infants. However, because the placenta continues to perform gas exchange after delivery, sick and preterm infants are likely to benefit most from additional blood volume derived from continued placental transfusion. Another concern is that a delay in umbilical cord clamping could increase the potential for excessive placental transfusion. To date, the literature does not show evidence of an increased risk of polycythemia or jaundice; however, in some studies there is a slightly higher rate of jaundice that meets criteria for phototherapy in term infants. Given the benefits to most newborns and concordant with other professional organizations, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists now recommends a delay in umbilical cord clamping for at least 30–60 seconds after birth in vigorous term and preterm

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric Practice 18 makes the following recommendations regarding the timing of umbilical cord clamping after birth:

- In term infants, delayed umbilical cord clamping (umbilical cord clamping more than 5 minutes after birth) increases hemoglobin levels at birth and improves iron stores in the first several months of life, which may have a favorable effect on developmental outcomes.

- Delayed umbilical cord clamping is associated with significant neonatal benefits in preterm infants, including improved transitional circulation, better establishment of red blood cell volume, decreased need for blood transfusion, and lower incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis and intraventricular hemorrhage.

- Given the benefits to most newborns and concordant with other professional organizations, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists now recommends a delay in umbilical cord clamping in vigorous term and preterm infants for at least 30–60 seconds after birth.

- There is a small increase in the incidence of jaundice that requires phototherapy in term infants undergoing delayed umbilical cord clamping. Consequently, obstetrician–gynecologists and other obstetric care providers adopting delayed umbilical cord clamping in term infants should ensure that mechanisms are in place to monitor and treat neonatal jaundice.

- Delayed umbilical cord clamping does not increase the risk of postpartum hemorrhage.

Neonatal outcomes

Physiologic studies in term infants have shown that a transfer from the placenta of approximately 80 mL of blood occurs by 1 minute after birth, reaching approximately 100 mL at 3 minutes after birth 21. Initial breaths taken by the newborn appear to facilitate this placental transfusion 22. A recent study of umbilical cord blood flow patterns assessed by Doppler ultrasonography during delayed umbilical cord clamping 23 showed a marked increase in placental transfusion during the initial breaths of the newborn, which is thought to be due to the negative intrathoracic pressure generated by lung inflation. This additional blood supplies physiologic quantities of iron, amounting to 40–50 mg/kg of body weight. This extra iron has been shown to reduce and prevent iron deficiency during the first year of life 24 Iron deficiency during infancy and childhood has been linked to impaired cognitive, motor, and behavioral development that may be irreversible 13. Iron deficiency in childhood is particularly prevalent in low-income countries but also is common in high-income countries, where rates range from 5% to 25% 13.

A longer duration of placental transfusion after birth also facilitates transfer of immunoglobulins and stem cells, which are essential for tissue and organ repair. The transfer of immunoglobulins and stem cells may be particularly beneficial after cellular injury, inflammation, and organ dysfunction, which are common in preterm birth 25. The magnitude of these benefits requires further study, but this physiologic reservoir of hematopoietic and pluripotent stem cell lines may provide therapeutic effects and benefit for the infant later in life 26.

Maternal outcomes

Immediate umbilical cord clamping has traditionally been carried out along with other strategies of active management in the third stage of labor in an effort to reduce postpartum hemorrhage. Consequently, concern has arisen that delayed umbilical cord clamping may increase the risk of maternal hemorrhage. However, recent data do not support these concerns. In a review of five trials that included more than 2,200 women, delayed umbilical cord clamping was not associated with an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage or increased blood loss at delivery, nor was it associated with a difference in postpartum hemoglobin level or need for blood transfusion 6. However, when there is increased risk of hemorrhage (eg, placenta previa or placental abruption), the benefits of delayed umbilical cord clamping need to be balanced with the need for timely hemodynamic stabilization of the woman (Table 1).

Lotus birth summary

In summary, in the light of what has been expounded above, it can be claimed that the practice of Lotus Birth is inadvisable from both the scientific and logical/rational points of view 1. Furthermore, it must also be pointed out that, if the Lotus Birth “guidelines” are followed to the letter, the lack of clamping could give rise to a potential thrombotic risk, in that the establishment of a low-flow, low-resistance circulation, like that of the fetus-placenta post-partum could facilitate the formation of blood clots. Similarly, cases of idiopathic neonatal hepatitis 3 and neonatal omphalitis 2 following Lotus Birth have been described in the literature.

References- Bonsignore A, Buffelli F, Ciliberti R, Ventura F, Molinelli A, Fulcheri E. Medico-legal considerations on “Lotus Birth” in the Italian legislative framework. Ital J Pediatr. 2019;45(1):39. Published 2019 Mar 18. doi:10.1186/s13052-019-0632-z https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6423792

- Steer-Massaro C. Neonatal Omphalitis After Lotus Birth. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2020;65(2):271‐275. doi:10.1111/jmwh.13062

- Tricarico A, Bianco V, Di Biase AR, Iughetti L, Ferrari F, Berardi A. Lotus Birth Associated With Idiopathic Neonatal Hepatitis. Pediatr Neonatol. 2017;58(3):281‐282. doi:10.1016/j.pedneo.2015.11.010

- Zinsser LA. Lotus birth, a holistic approach on physiological cord clamping. Women Birth. 2018;31:e73–e76. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2017.08.127

- Crowther S. Lotus birth: leaving the cord alone. Pract Midwife. 2006;9:12–14.

- McDonald SJ, Middleton P, Dowswell T, Morris PS. Effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping of term infants on maternal and neonatal outcomes. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013, Issue 7. Art. No.: CD004074 . DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004074.pub3

- Linderkamp O. Placental transfusion: determinants and effects. Clin Perinatol 1982;9:559–92.

- Philip AG, Saigal S. When should we clamp the umbilical cord? Neoreviews 2004;5:e142–54.

- Yao AC, Lind J. Effect of gravity on placental transfusion. Lancet 1969;2:505–8.

- Vain NE, Satragno DS, Gorenstein AN, Gordillo JE, Berazategui JP, Alda MG, et al. Effect of gravity on volume of placental transfusion: a multicentre, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2014;384:235–40.

- Valero J, Desantes D, Perales-Puchalt A, Rubio J, Diago Almela VJ, Perales A. Effect of delayed umbilical cord clamping on blood gas analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2012;162:21–3.

- De Paco C, Florido J, Garrido MC, Prados S, Navarrete L. Umbilical cord blood acid-base and gas analysis after early versus delayed cord clamping in neonates at term. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2011;283:1011–4.

- Andersson O, Lindquist B, Lindgren M, Stjernqvist K, Domellof M, Hellstrom-Westas L. Effect of delayed cord clamping on neurodevelopment at 4 years of age: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr 2015;169:631–8.

- Al-Wassia H, Shah PS. Efficacy and safety of umbilical cord milking at birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr . 2015 Jan;169(1):18–25.

- Jaiswal P, Upadhyay A, Gothwal S, Singh D, Dubey K, Garg A, et al. Comparison of two types of intervention to enhance placental redistribution in term infants: randomized control trial. Eur J Pediatr 2015;174:1159–67.

- Katheria AC, Truong G, Cousins L, Oshiro B, Finer NN. Umbilical cord milking versus delayed cord clamping in preterm infants. Pediatrics 2015;136:61–9.

- Rabe H, Sawyer A, Amess P, Ayers S. Neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 and 3.5 years for very preterm babies enrolled in a randomized trial of milking the umbilical cord versus delayed cord clamping. Brighton Perinatal Study Group. Neonatology 2016;109:113–9.

- Delayed Umbilical Cord Clamping After Birth. Committee Opinion Number 684, January 2017 https://www.acog.org/-/media/project/acog/acogorg/clinical/files/committee-opinion/articles/2017/01/delayed-umbilical-cord-clamping-after-birth.pdf

- World Health Organization. WHO Recommendations for the Prevention and Treatment of Postpartum Haemorrhage. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012.

- American College of Nurse Midwives. Delayed umbilical cord clamping. Position Statement. Silver Spring (MD): ACNM; 2014. http://www.midwife.org/ACNM/files/ACNMLibraryData/UPLOADFILENAME/000000000290/Delayed-Umbilical-Cord-Clamping-May-2014.pdf

- Linderkamp O, Nelle M, Kraus M, Zilow EP. The effect of early and late cord-clamping on blood viscosity and other hemorheological parameters in full-term neonates. Acta Paediatr 1992;81:745–50.

- Bhatt S, Alison BJ, Wallace EM, Crossley KJ, Gill AW, Kluckow M, et al. Delaying cord clamping until ventilation onset improves cardiovascular function at birth in preterm lambs. J Physiol 2013;591:2113–26.

- Boere I, Roest AA, Wallace E, Ten Harkel AD, Haak MC, Morley CJ, et al. Umbilical blood flow patterns directly after birth before delayed cord clamping. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2015;100:F121–5.

- Pisacane A. Neonatal prevention of iron deficiency. BMJ 1996;312:136–7.

- Sanberg PR, Park DH, Borlongan CV. Stem cell transplants at childbirth. Stem Cell Rev 2010;6:27–30.

- Sanberg PR, Divers R, Mehindru A, Mehindru A, Borlongan CV. Delayed umbilical cord blood clamping: first line of defense against neonatal and age-related disorders. Wulfenia 2014;21:243–9.