Maxillary hypoplasia

Maxillary hypoplasia also known as pseudoprognathism, is a bone malformation in which the maxillary bones (upper jaw) is underdeveloped, creating the illusion of protuberance of the lower jaw (mandible) giving the face a protruding jaw (prognathic) appearance that is apparent but in many cases not real, hence it is also known as “false prognathism”. In most cases, maxillary hypoplasia is a developmental anomaly in cleft lip and palate deformities, although it can also be caused by external factors, such as poorly planned dental extractions.

In a large part of the cases of maxillary hypoplasia, the maxilla is underdeveloped not only in the anteroposterior plane, but also presents deficiencies in the vertical or transverse plane, giving a sunken appearance to the middle third of the patient’s face, and making both the nose and the jaw protrude and appear very prominent, even if they have a normal size and are in correct proportion with the rest of the facial features.

Maxillary augmentation is indicated when any part of the maxilla is hypoplastic and creates an aesthetic or functional deficiency. If malocclusion exists, surgeries that create osteotomies, such as Le Fort I-type fractures, anterior maxillary displacement, maxillary osteotomies 1 and other orthognathic procedures, can be used 2.

Often, maxillary augmentation is undertaken in orthodontic procedures and in elongation of the vertical length of the face 3. Various materials such as calvarial and iliac bone grafts 4, as well as costal cartilage grafts, have been used 5. Goh and Chen 1 used silastic nasal implants in cases in which earlier surgery was required.

Lefort 1 advancement is the traditional management modality for correction of the maxillary hypoplasia in cleft lip and palate patients but the alteration of the speech and relapse rate after Lefort 1 advancement is significant 6. Distraction also has significant risk of velopharyngeal insufficiency 7. Anterior maxillary distraction for maxillary hypoplasia secondary to cleft lip and palate has the advantage of fewer chances of velopharyngeal insufficiency, speech alteration and lesser relapse rates 8.

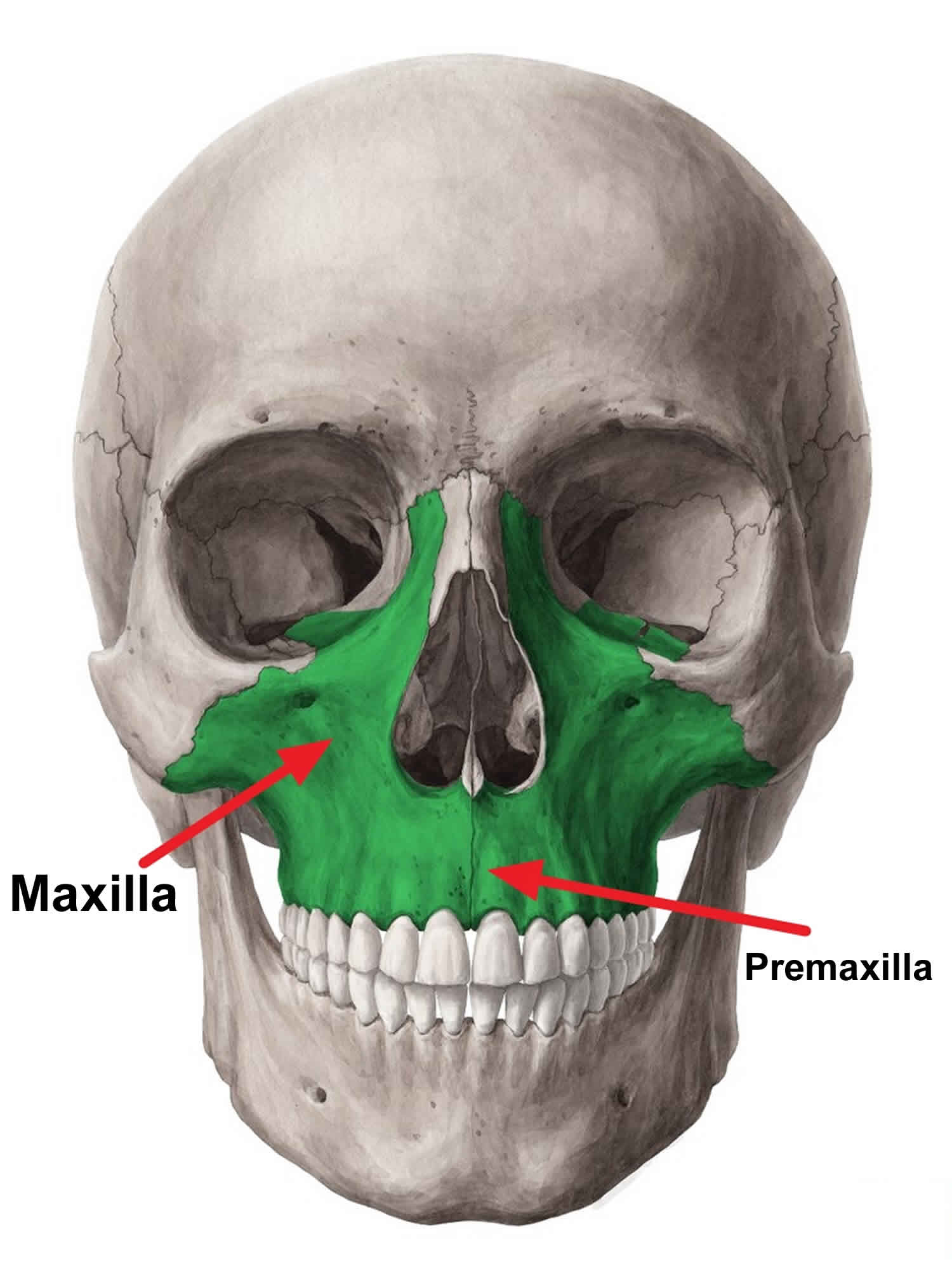

Figure 1. Maxilla

Maxillary hypoplasia causes

Congenital, acquired, or developmental maxillary hypoplasia can occur.

Craniofacial anomalies, Apert syndrome, and Crouzon syndrome include maxillary and cranial hypoplasia 9.

More localized anomalies, such as Binder syndrome, also known as maxillonasal dysplasia, refers to congenital maxillary hypoplasia. In Binder syndrome, the anterior nasal spine, nasal bone, and anterior maxillary hypoplasia are affected. These patients have a concave mid face with a C-shaped profile; a blunted, short nose; and an acute columella-labial angle 10. A 17-year retrospective study recommended surgery in the midteenage years in these patients, thereby allowing the mid face to mature 1. Gewalli et al 11 had good results with both bone and cartilage in these patients. Holmes et al 12 preferred the use of serial silicone implants for prepuberty expansion and then placement of costochondral cartilage.

Cleft palate and labial deformities are often coupled with premaxillary hypoplasia, resulting in an acute columella-labial angle, ptosis of the nasal tip, and upper labial retraction, with possible exposure of the upper gingiva 13.

Causes of acquired maxillary hypoplasia are often from trauma or from malposition of the maxillary bone following surgery. Converse et al 14 have postulated that during childhood, trauma can have a retarding effect on facial development.

Developmental hypoplasia may be a complication to dental extraction, with failure of the maxillary bone to properly mature and expand.

Patients of Northern European ancestry, including English descendants, can have maxillary hypoplasia 15.

Premaxillary hypoplasia is often observed in patients of Hispanic, African American, and Asian (mesorrhine) heritage. Platyrrhine (African American) noses can also appear flared with widened alae, insufficient dorsal nasal support, and underprojection of the nasal tip 16.

Maxillary hypoplasia symptoms

Maxillary hypoplasia malformation creates the illusion of a prominent jaw and nose, even if both sides have a normal size and in correct proportion to the face.

Maxillary hypoplasia diagnosis

Cephalograms and CT, including 3-dimensional reconstruction, can be used, if desired, to assess the degree of retrusion.

Photographs from frontal and profile view (lateral and obliques if desired) are extremely helpful and are all that is needed to assess the degree of retrusion in most patients.

Newer imaging capabilities allowing for more readily available customizable implant creation will become more prevalent. This technology, coupled with newer implant materials, will lead to less traumatic surgical techniques and elevated patient and physician satisfaction levels.

Maxillary hypoplasia treatment

The indicated treatment for maxillary hypoplasia is a monomaxillary orthognathic surgery, usually of maxillary advancement combined with other movements (descent, rotation, etc.). On the other hand, in some cases the lower development of the upper jaw leads to a compensation mechanism in the lower jaw; leading to cases in which the patient presents both mandibular prognathism (prominent jaw) and maxillary hypoplasia. In such cases, the treatment should be a bimaxillary orthognathic surgery, which will correct the position of both bone structures at the same time. Once the maxilla is in place, the patient’s features look softer and more balanced, and the nose gives the illusion of being smaller, even if its size hasn’t really been changed.

Maxillary hypoplasia surgery

In the recent years there has been a rapid advancement in the field of distraction osteogenesis for correction of defects, congenital or acquired, in the oral and maxillofacial region.

Literature shows that clinical research was carried out by various centers to determine the optimal protocols for anterior maxillary distraction 8.

Block and Brister (1994) 17 and Altuna et al. (1995) 18 examined anterior segmental distraction osteogenesis experimentally in the maxilla. Altuna et al. 19 used a modified occlusal splint as tooth borne device on primates. They determined that anterior segment movement with distraction osteogenesis is a reliable method and can be applied clinically. Wassmund in 1926 distracted the maxilla using distraction osteogenesis, followed by Rosenthal in 1927 who used distraction osteogenesis in distracting anterior mandible 20. William Bell 21 used a Wassmund osteotomy to correct anterior maxillary retrusion and class III malocclusion. The advancement of the anterior maxilla is difficult with osteotomy and can be complicated by oro nasal fistula formation.

Dolonmaz et al. 22 first described anterior maxillary distraction using two parts acrylic appliance with Hyrax screw. The acrylic plate covers the tooth occlusal surface that can lift the occlusion. In our cases we have not used acrylic splints for lifting the occlusion.

Bengi et al. 23 used an individual tooth borne distraction device to advance the maxillary segment. The results showed that the premaxilla moved antero superiorly. The soft tissue profile showed improvement, the length of the palatal plane and maxillary arch increased and sufficient space was gained to align the crowded teeth.

In a case report, Karakasis and Hadjiperous 24 presented gradual distraction osteogenesis using two intraoral bone borne unidirectional devices of Zurich ramus distractor for anterior maxillary advancement, resulting in satisfactory final occlusion and considerable aesthetic improvement.

Wang et al. 25 in a clinical study showed an advancement of 10.5 mm of anterior maxilla with no significant velopharyngeal insufficiency using internal distraction device and external distraction device. In our cases we achieved 10 mm of advancement with no alteration in speech.

Keudstall et al. 26 used Rotterdam palatal distractor-bone borne distractor for the expansion of the transverse hypoplastic patients, like in cleft palate. It gives more of an orthopedic expansion of the maxilla rather than tooth tipping.

In bi jaw deformity secondary to cleft lip and palate patients, anterior maxillary distraction along with Bilateral Sagittal Split Osteotomy have fewer complications in respect of velopharyngeal insufficiency and relapse rate as compared to traditional method of Lefort 1 and Bilateral Sagittal Split Osteotomy 8.

In traditional methods relapse of 20–60 % 27 have been reported in literature. Relapse of distracted anterior maxilla can occur in cleft lip and palate patients. Velopharyngeal insufficiency after Lefort 1 advancement is due to a stretch on the palatal musculature, worsening the velopharyngeal incompetence and hence the speech. Advantages of anterior maxillary distraction are that, it is a simple procedure as compared to Lefort 1 osteotomy, with fewer complications and less relapse, additionally speech is not affected.

Maxillary hypoplasia surgery complications

Complications related to the implant may arise.

If an autogenic implant is used, the possibility of donor site infection and scarring and autograft contamination exists.

Both synthetic and nonsynthetic grafts may extrude or become infected.

Patient dissatisfaction can also occur from an overcorrection or undercorrection or secondary to implant migration.

Paresthesias stemming from infraorbital nerve injury can result and persist indefinitely. Fortuitously, some paresthesias resolve within 6-12 months.

Maxillary hypoplasia prognosis

Most of the implant material is nonautogenous in nature. Silicone is relatively inert and has a long history of being well tolerated by the body. Infection can occur with any implanted material in the body. If this were to occur with the silicone implant, it would necessitate removal.

Slippage of the implant can also occur if the pocket is too large. Autogenous material such as cartilage is seldom used in this area. The increased effort to harvest this material and shave it is not often warranted. Septal cartilage can be fashioned into a maxillary onlay graft but “results in the long run may be less predictable than alloplastic correction” 15.

The patient and surgeon ultimately decide which implant material to use.

References- Goh RC, Chen YR. Surgical management of Binder’s syndrome: lessons learned. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2010 Dec. 34(6):722-30.

- Bottini DJ, Gentile P, Cervelli G, et al. Changes in nasal profile following maxillomandibular osteotomy for prognathism. Orthodontics (Chic.). 2013. 14(1):e30-8.

- Kim WS, Kim CH, Yoon JH. Premaxillary augmentation using autologous costal cartilage as an adjunct to rhinoplasty. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010 Sep. 63(9):e686-90.

- Kuik K, Putters TF, Schortinghuis J, van Minnen B, Vissink A, Raghoebar GM. Donor site morbidity of anterior iliac crest and calvarium bone grafts: A comparative case-control study. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2016 Apr. 44 (4):364-8.

- Guerrerosantos J, Sterzi C. Interpositional cartilage grafts to improve vertical length of the face. J Craniofacial Surg. Nov 2012. 21(6):1666-9.

- Hirano A, Suzuki H. Factors related to relapse after Le Fort I maxillary advancement osteotomy in patients with cleft lip and palate. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2001;38(1):1-10. doi:10.1597/1545-1569_2001_038_0001_frtral_2.0.co_2

- Guyette TW, Polley JW, Figueroa A, Smith BE. Changes in speech following maxillary distraction osteogenesis. Cleft Palate Craniofac J. 2001;38(3):199-205. doi:10.1597/1545-1569_2001_038_0199_cisfmd_2.0.co_2

- Chacko T, Vinod S, Mani V, George A, Sivaprasad KK. Management of Cleft Maxillary Hypoplasia with Anterior Maxillary Distraction: Our Experience. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. 2014;13(4):550-555. doi:10.1007/s12663-013-0521-8 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4518778

- Maxillary Augmentation Rhinoplasty. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1292328-overview#a9

- Watanabe T, Matsuo K. Augmentation with cartilage grafts around the pyriform aperture to improve the midface and profile in binder’s syndrome. Ann Plast Surg. 1996 Feb. 36(2):206-11.

- Gewalli F, Berlanga F, Monasterio FO, Holmström H. Nasomaxillary reconstruction in Binder syndrome: bone versus cartilage grafts. A long-term intercenter comparison between Sweden and Mexico. J Craniofac Surg. 2008 Sep. 19(5):1225-36.

- Holmes AD, Lee SJ, Greensmith A, Heggie A, Meara JG. Nasal reconstruction for maxillonasal dysplasia. J Craniofac Surg. 2010 Mar. 21(2):543-51.

- Cook TA, Wang TD, Brownrigg PJ, Quatela VC. Significant premaxillary augmentation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990 Oct. 116(10):1197-201.

- Converse JM, Horowitz SL, Valauri AJ, Montandon D. The treatment of nasomaxillary hypoplasia. A new pyramidal naso-orbital mazillary osteotomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1970 Jun. 45(6):527-35.

- Flowers RS. Augmentation maxilloplasty. Terino EO, Flowers RS, eds. The Art of Alloplastic Facial Contouring. Mosby: St Louis; 2000. 129-150.

- Romo T 3rd, Shapiro AL. Aesthetic reconstruction of the platyrrhine nose. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992 Aug. 118(8):837-41.

- Block MS, Brister GD. Use of distraction osteogenesis for maxillary advancement: preliminary results. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1994;52:282–286. doi: 10.1016/0278-2391(94)90301-8

- Altuna G, Walker DA, Freeman E. Surgically assisted rapid orthodontic lengthening of the maxilla in primates—a pilot study. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop. 1995;107:531–536. doi: 10.1016/S0889-5406(95)70120-6

- Altuna G, Walker DA, Freeman E. Surgically assisted rapid orthodopedic lengthening of the maxilla in primates—relapse following distraction osteogenesis. Int J Adult Orthodon Orthognath Surg. 1995;10:269–275.

- Stucki-McCormick SU. Reconstruction of the mandibular condyle using transport distraction osteogenesis. J Craniofac Surg. 1997;8:48–53. doi: 10.1097/00001665-199701000-00016

- Bell WH. Surgical correction of anterior maxillary retrusion: report of a case. J Oral Surg. 1968;26:57.

- Dolanmaz D, Karaman AI, Ozyesil AG. Maxillary anterior segmental advancement by using distraction osteogenesis: a case report. Angle Orthod. 2003;73:201–205.

- Bengi O, et al. Cephalometric evaluation of patients treated by maxillary anterior segmental distraction. A preliminary report. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2007;35:302–310. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2006.12.005

- KarakasisD Hadjiperous L. Advancement of anterior maxilla by distraction. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2004;32:150–154. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2003.09.009

- Wang XX, et al. Anterior maxillary segmental distraction for correction of maxillary hypoplasia and dental crowding in cleft palate patients: a preliminary report. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38:1237–1243. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.06.028

- Koudstaal MJ, VanDer Wal KGH, Wolvius EB, Schulten AJM. The Rotterdam palatal distractor: introduction of the new bone borne device and report of the pilot study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2006;35:31–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2005.07.002

- Posnick JC, Dagys AP. Skeletal stability and relapse patterns after Le Fort I maxillary osteotomy fixed with miniplates: the unilateral cleft lip and palate deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;94:924–932. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199412000-00004